For J.D.P and Paul -14 November 2025

In construction….

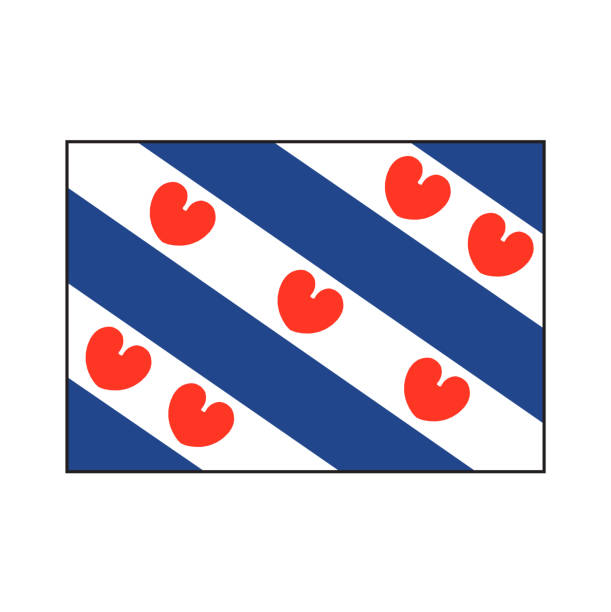

The term “Frisian heart” refer often to two distinct yet related concepts: the symbolic heart

seen on the Frisian flag and the genetic heart condition prevalent among those of Frisian

ancestry.

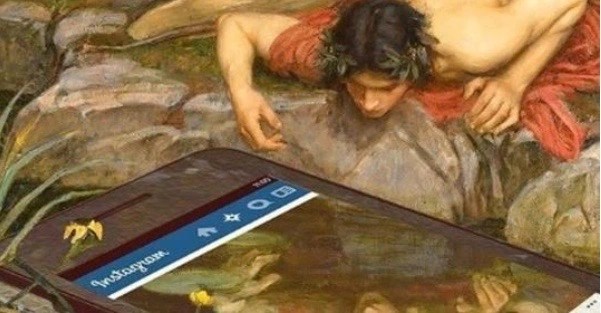

The machine, is the term used by novelist, poet, and essayist Paul Kingsnorth to present how a force that’s hard to name, but which we all feel, is reshaping what it means to be human. A wholly original―and terrifying―account of the technological-cultural matrix enveloping all of us. With insight into the spiritual and economic roots of techno-capitalism, Kingsnorth reveals how the Machine, in the name of progress, has choked Western civilization, is destroying the Earth itself, and is reshaping us in its image. From the First Industrial Revolution to the rise of artificial intelligence, he shows how the hollowing out of humanity has been a long game―and how your very soul is at stake.

See more on Against the Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity

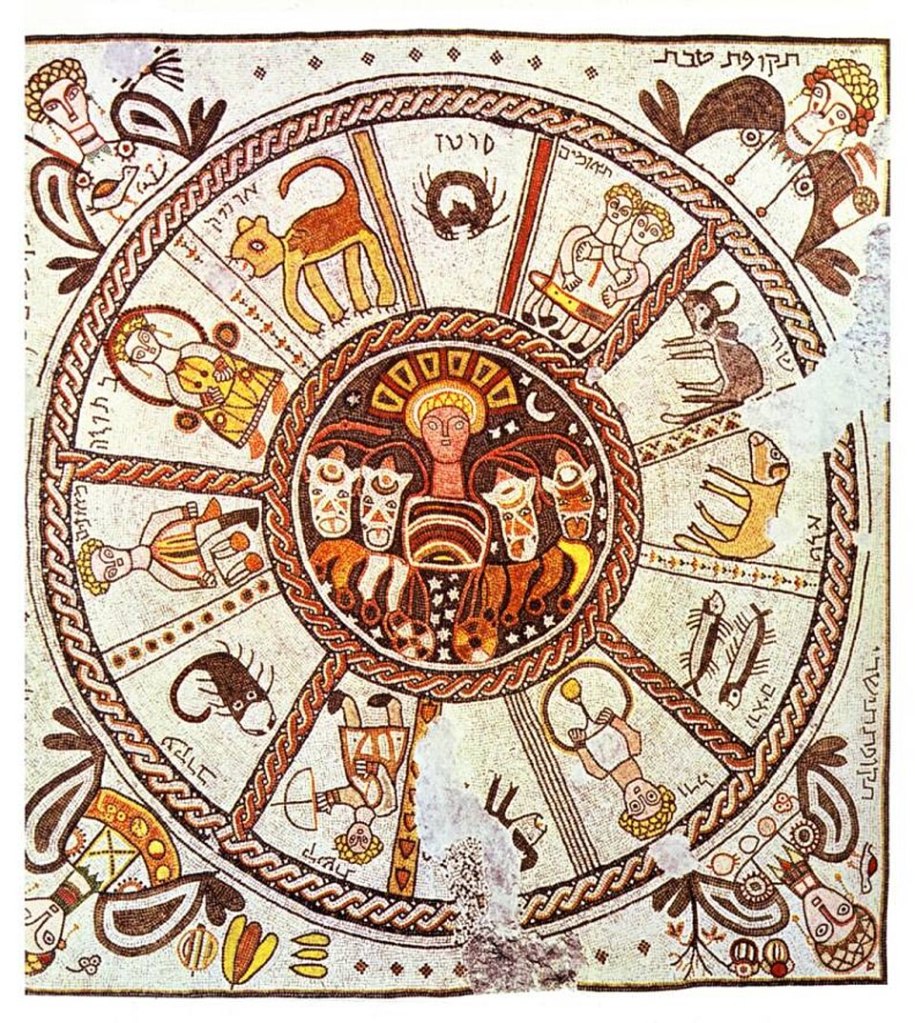

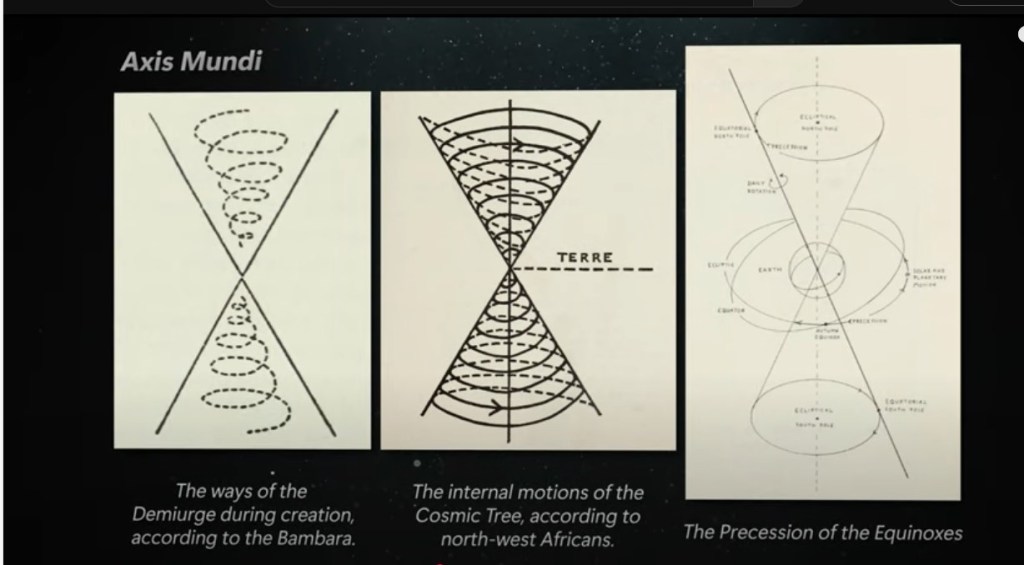

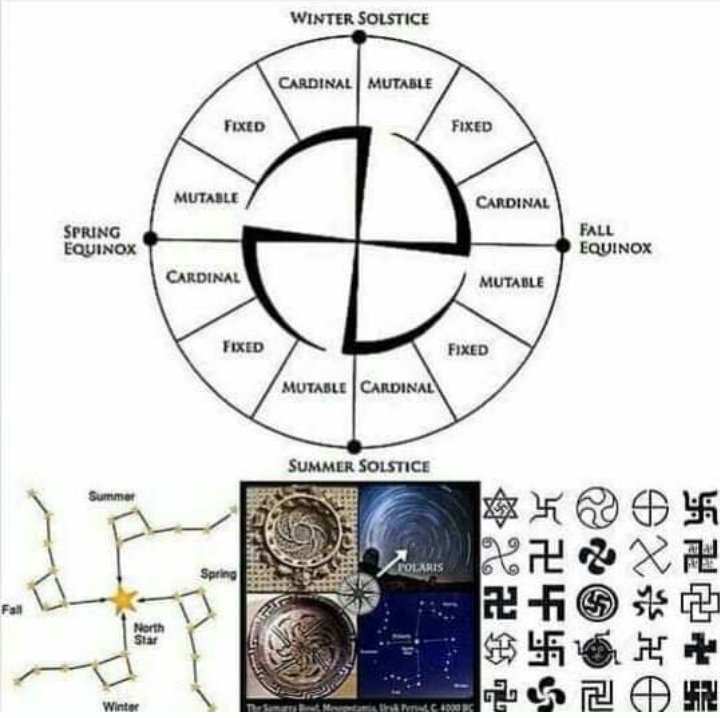

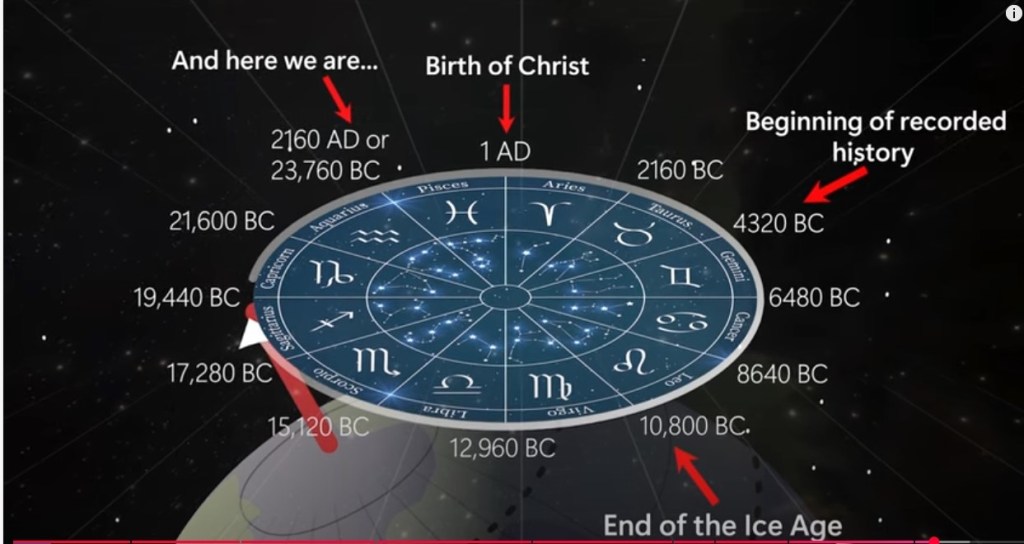

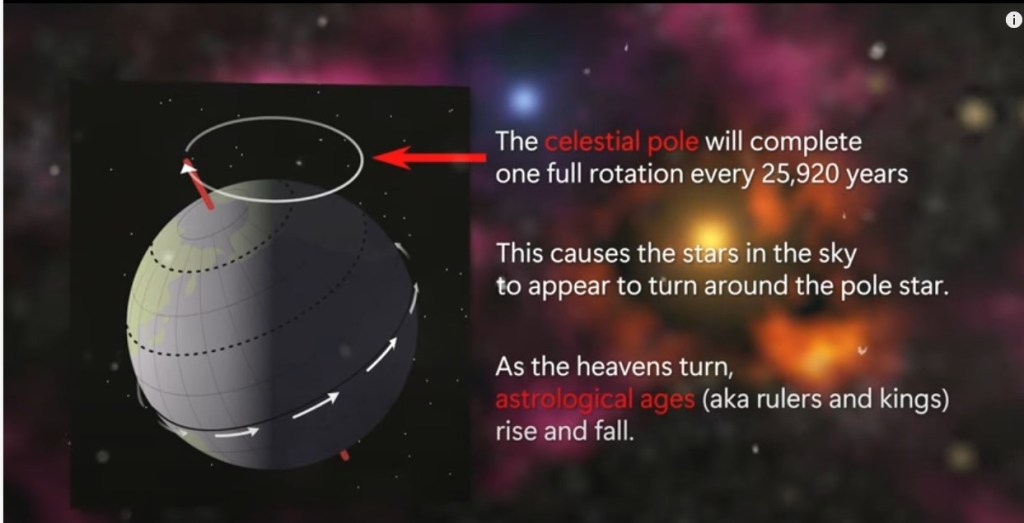

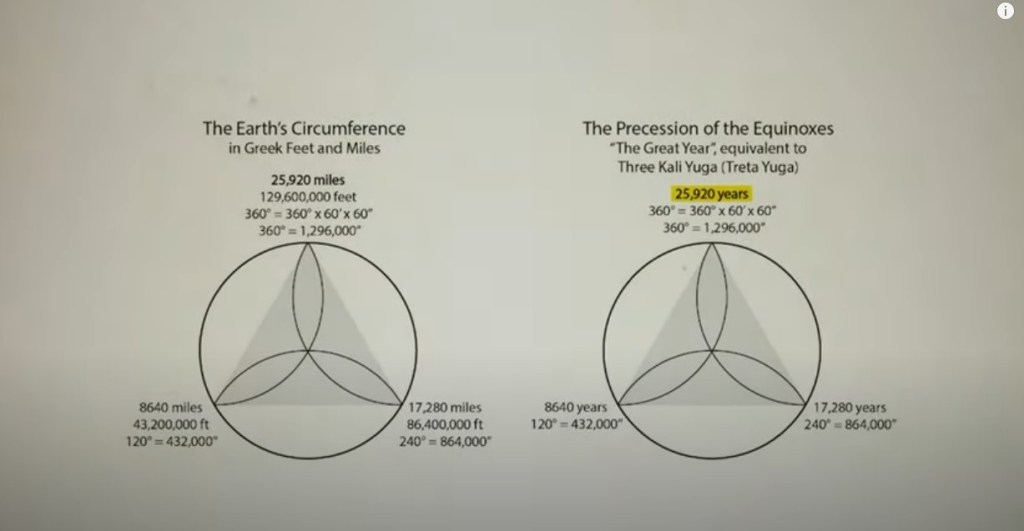

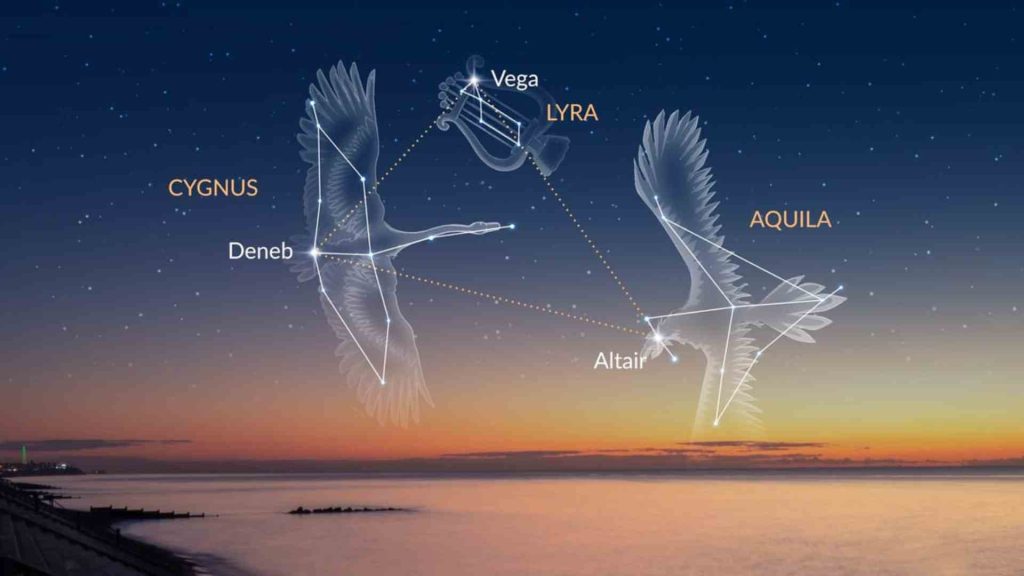

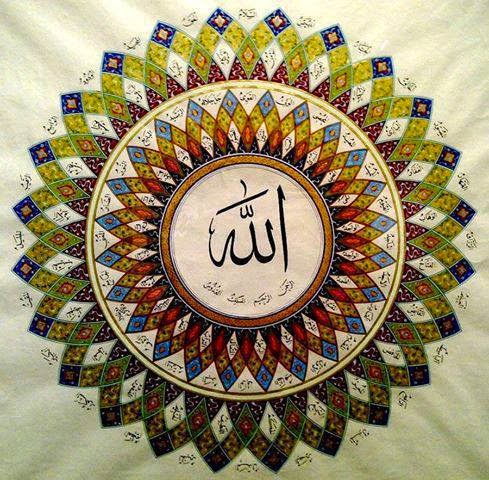

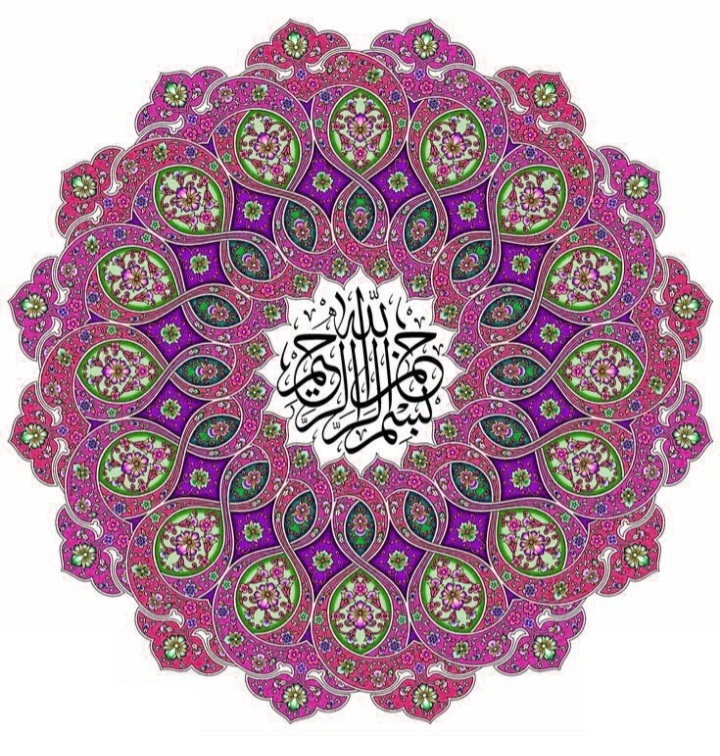

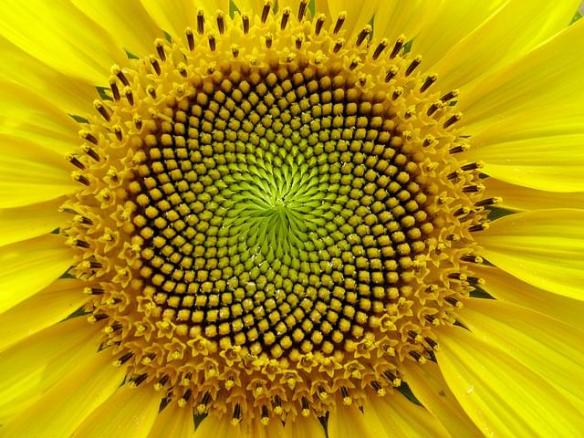

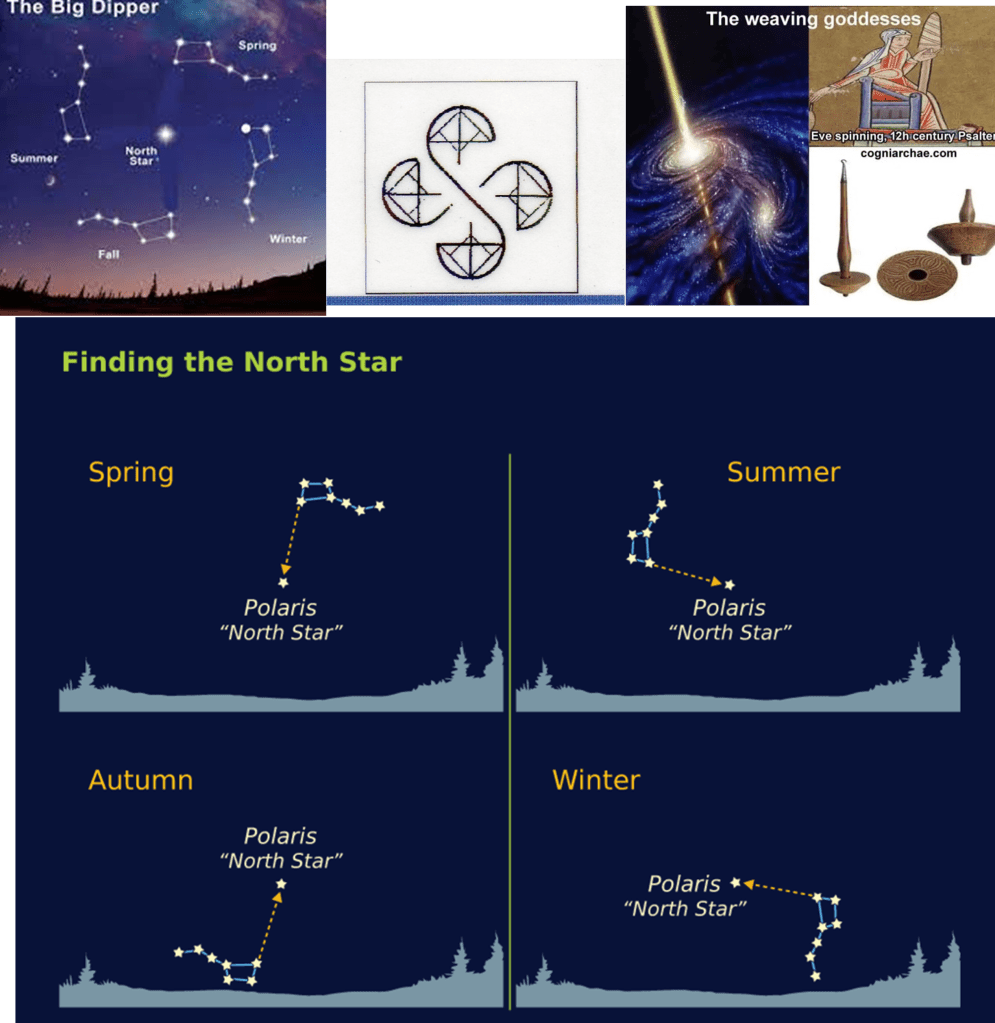

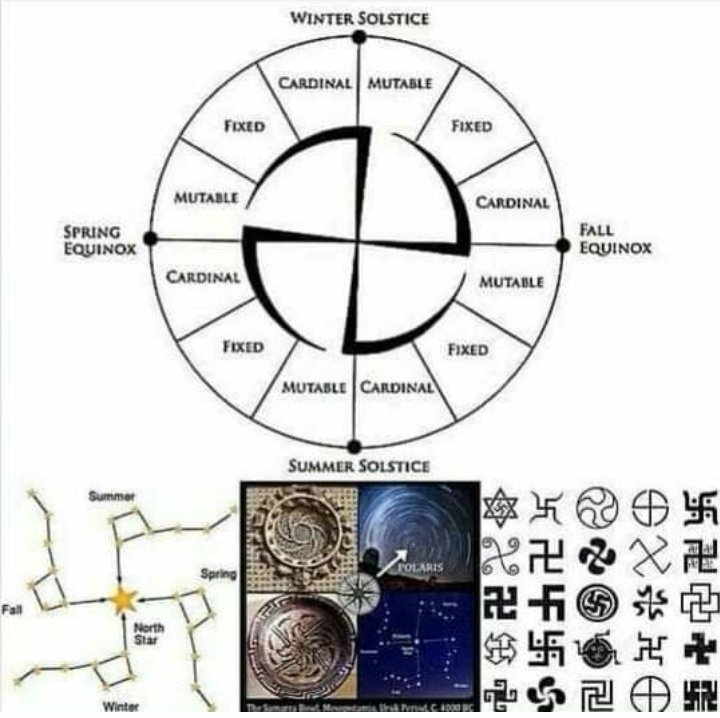

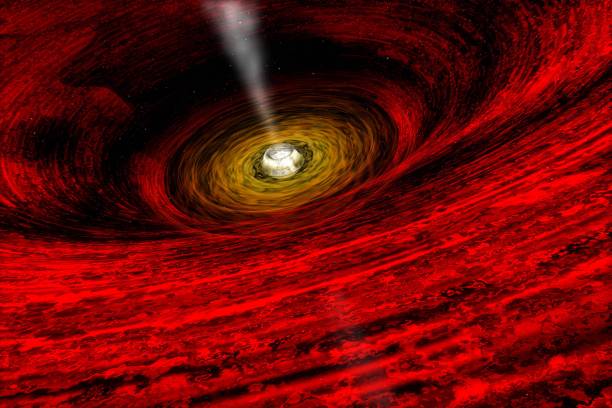

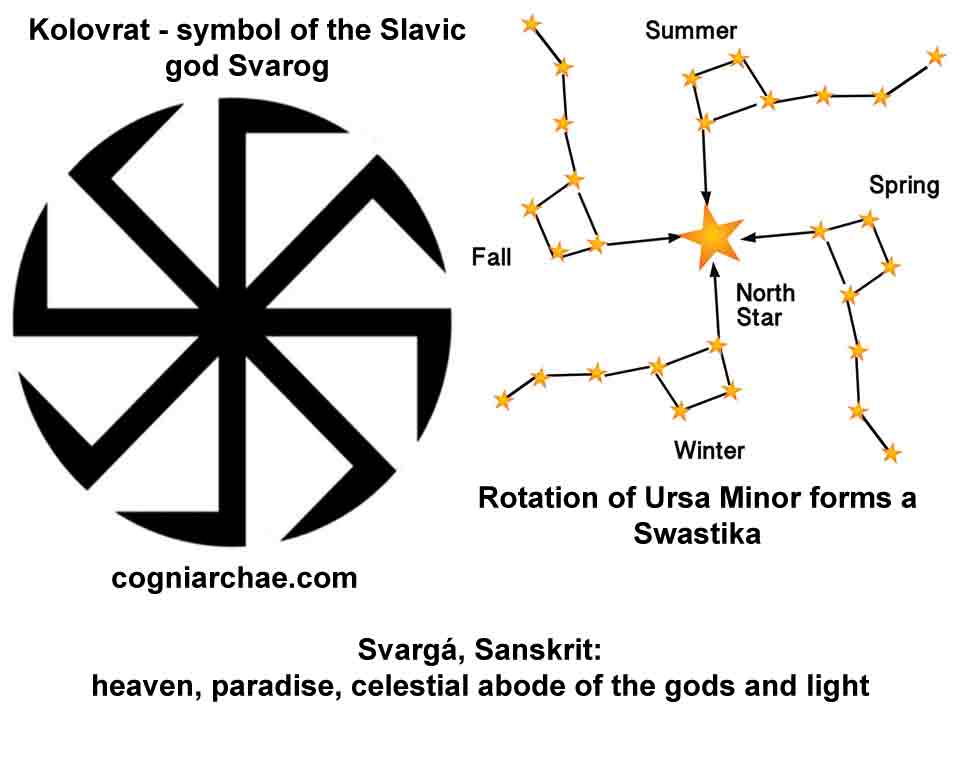

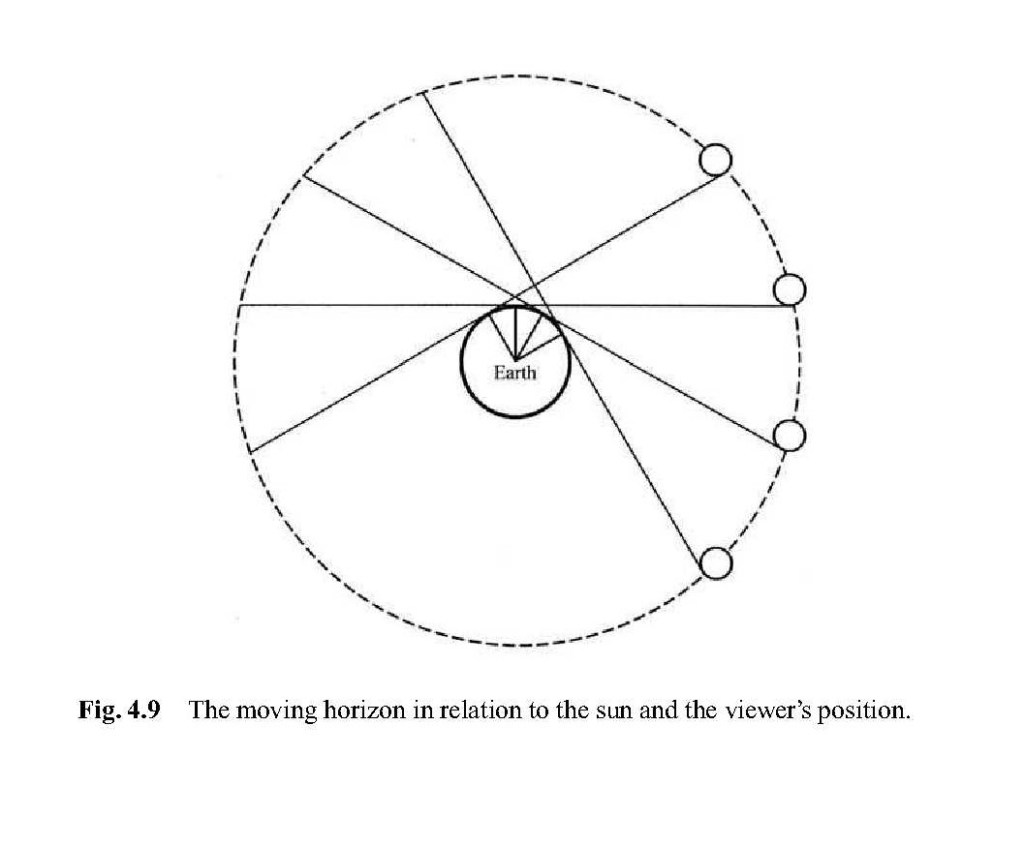

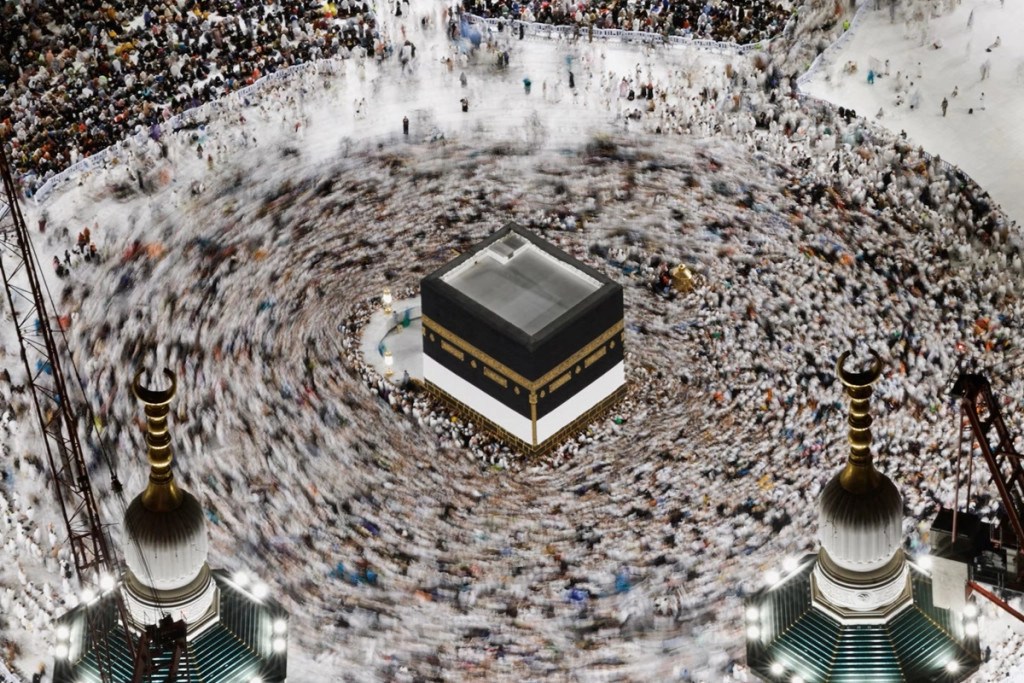

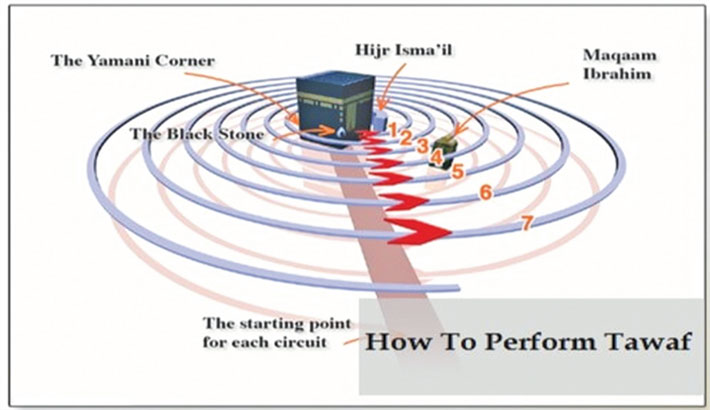

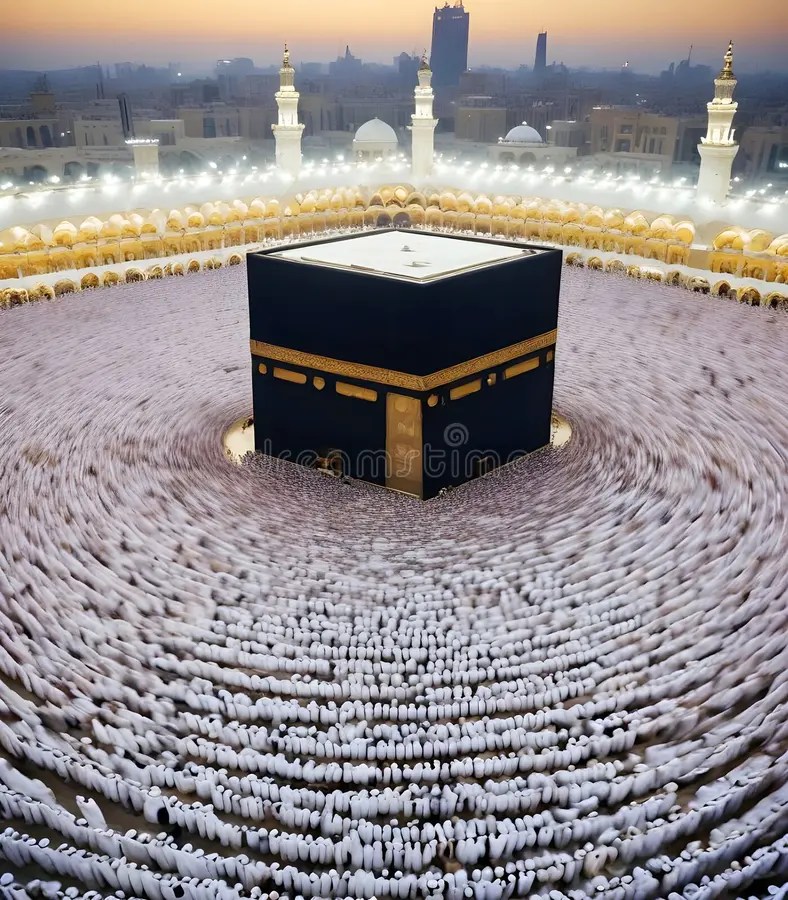

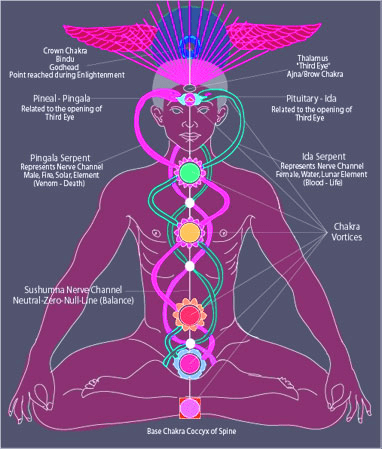

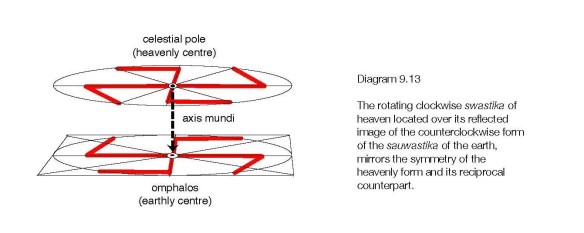

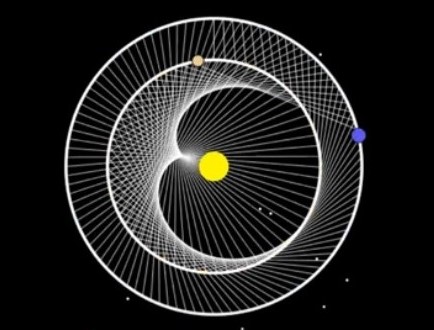

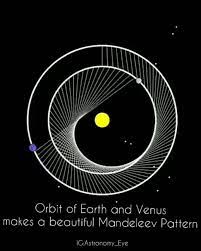

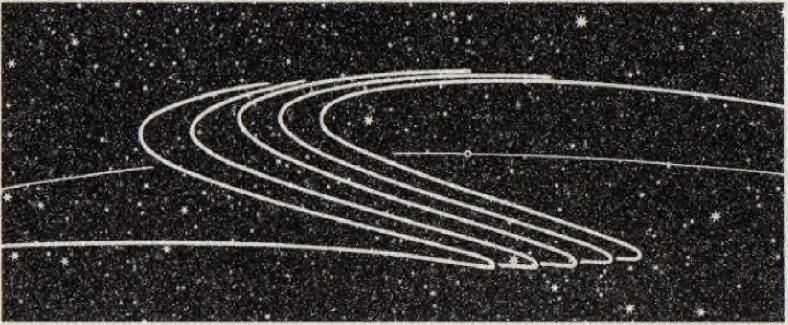

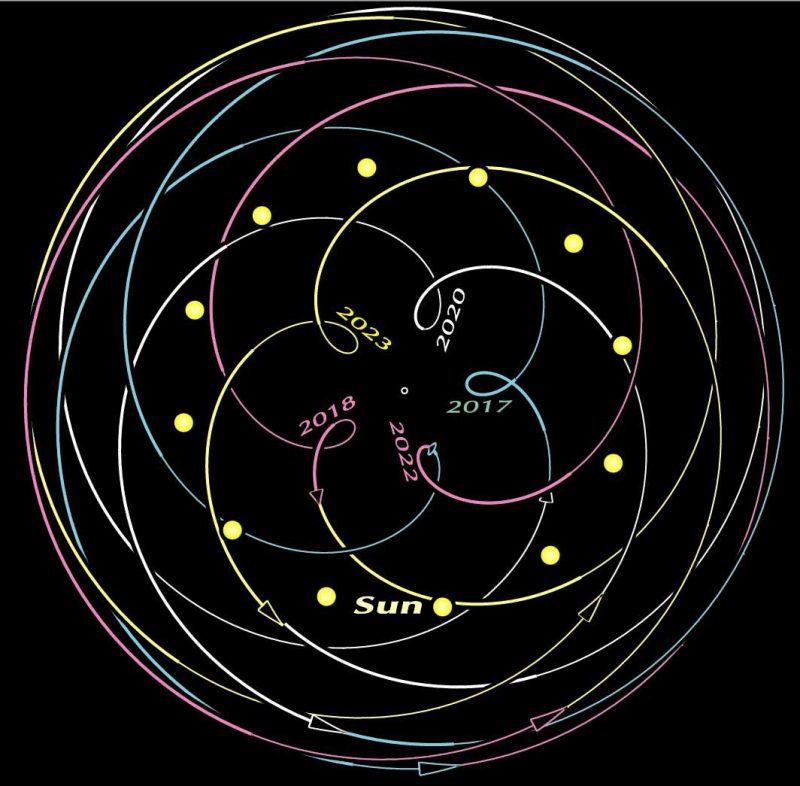

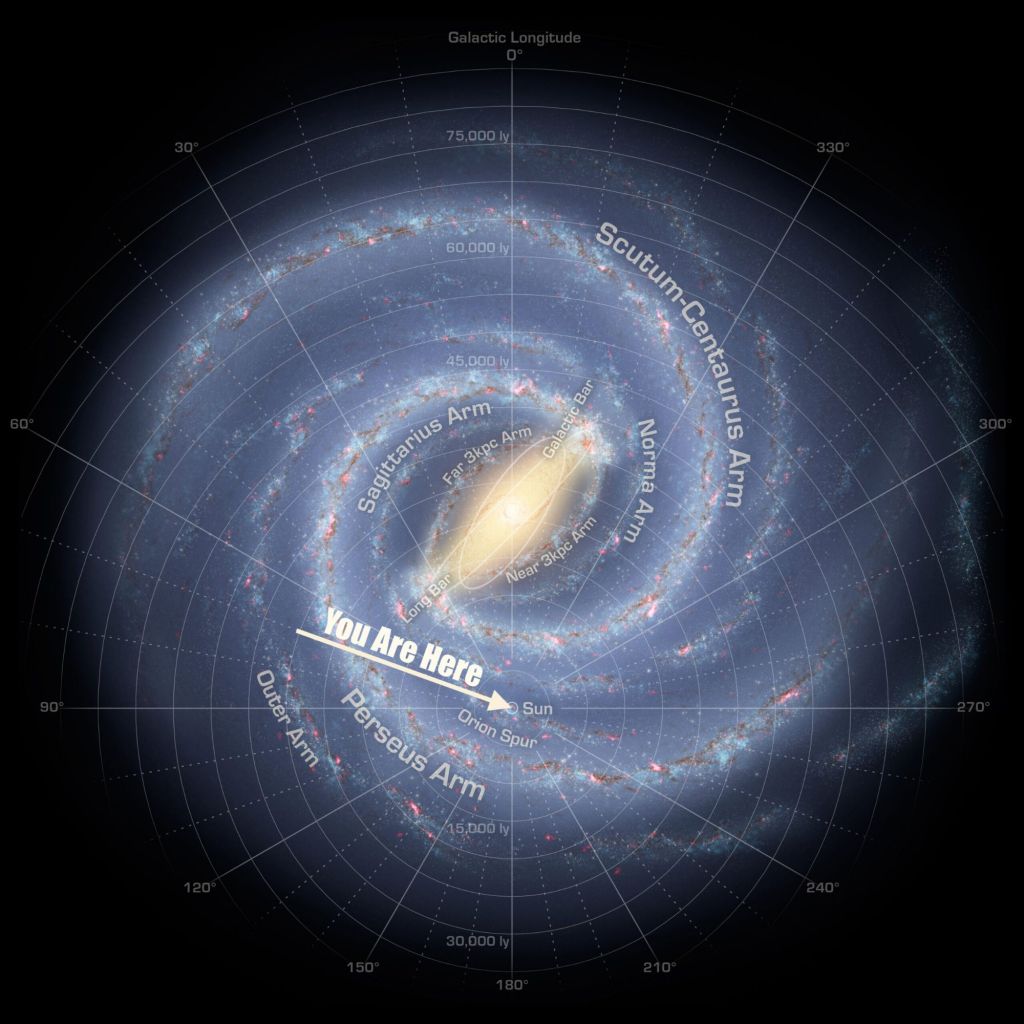

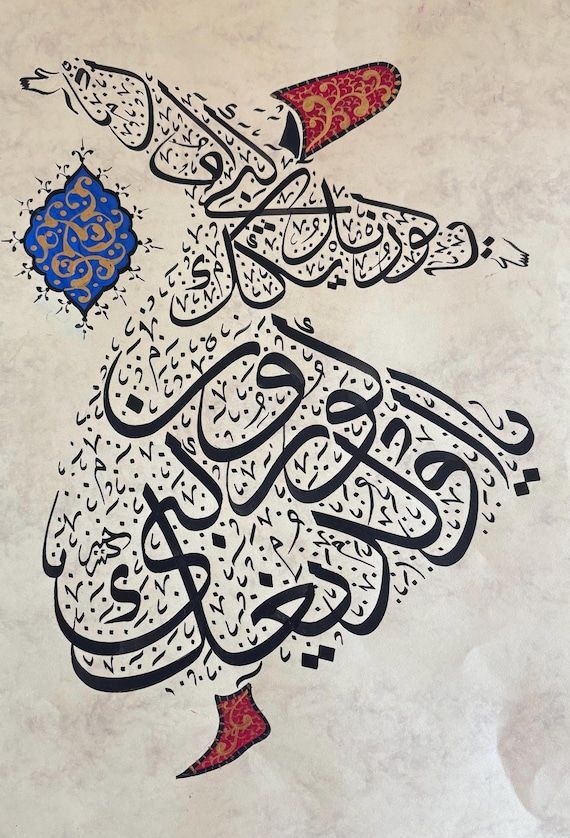

“Everything is whirling.” The first time that we heard the master the Grandsheikh Sultan Muhammad Nazim al Haqqani an-Naqshbandi say these words, we did not understand them. It would take years to see the truth hidden in that deceptively simple teaching. “Our soul is whirling in a completely different dimension, but even here every atom is whirling,” he says. He expands on the idea, pointing to the rotation of the earth itself, that of the moon trapped in orbit around it, and the two spinning around the sun. “Even the Milky Way is turning,”

Waht is generally saidin the time of the machins::

Symbol on the Frisian Flag

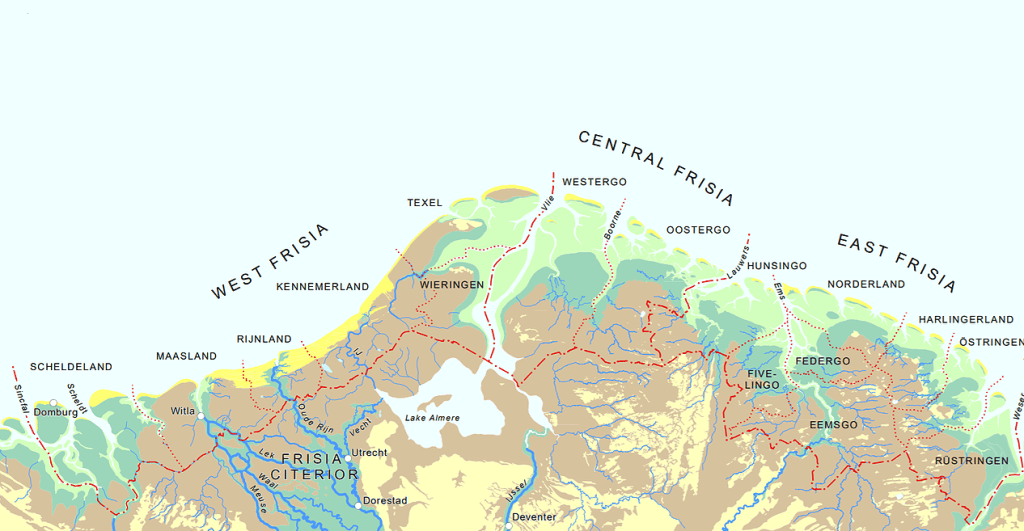

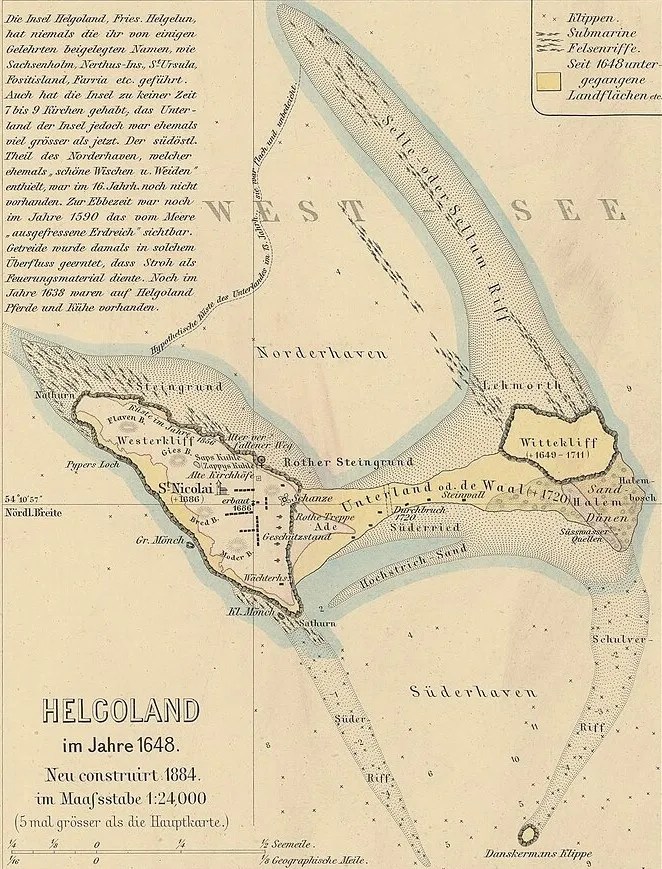

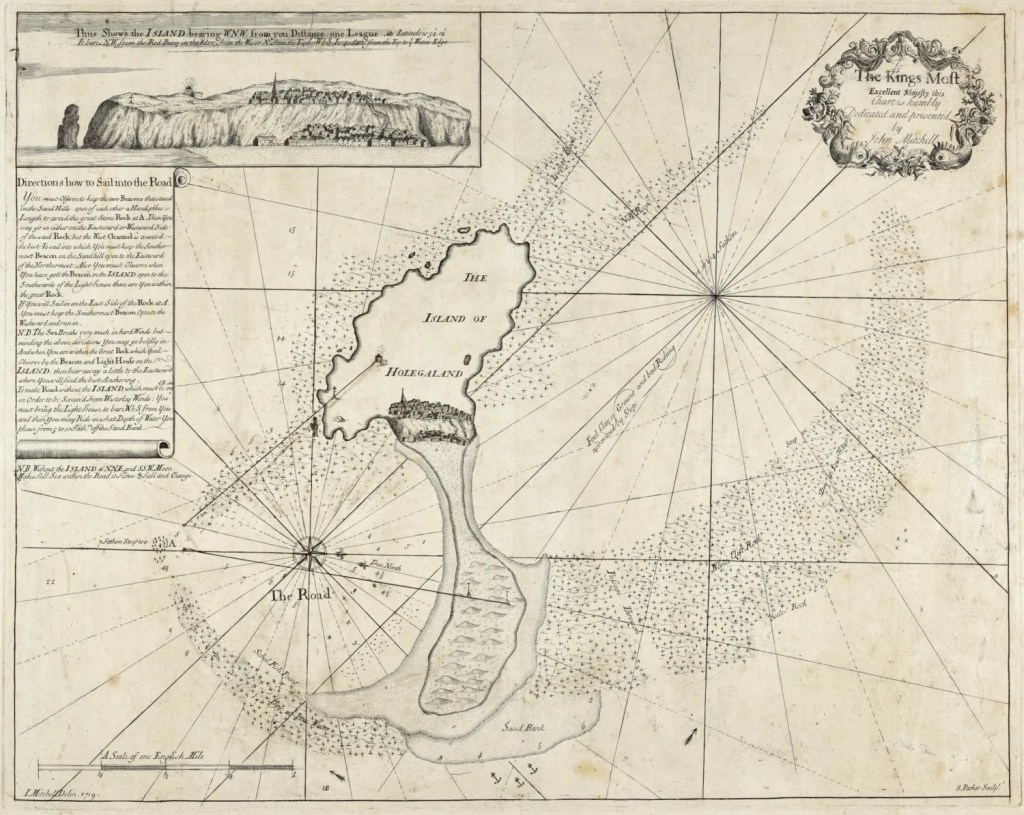

The Frisian flag, official in Friesland (Fryslân), features seven red, heart-shaped symbols called “pompeblêden” that actually represent leaves of the yellow water lily native to the region. These seven symbols are arranged diagonally across white stripes and are deeply associated with the region’s historic maritime territories. While commonly interpreted as hearts, they are not intended as romantic or anatomical symbols but carry cultural significance tied to Frisian history and identity.

Genetic Heart Condition: PLN Mutation

There is also a specific hereditary heart condition linked to Frisian descent—the PLN

(phospholamban) gene mutation. This genetic variant, first appearing in a Frisian ancestor

about 700 years ago, causes a form of cardiomyopathy leading to heart rhythm disorders,

potential heart failure, and even sudden cardiac death in undiagnosed cases. Symptoms can include reduced stamina, palpitations, arrhythmias, and cardiac arrest. It is estimated that 1 in 1,400 to 1,500 people in Friesland and nearby regions carry the mutation, with about 10,000–15,000 carriers in the Netherlands. The PLN mutation is passed down in families and is regarded as a “founder mutation,” with all modern carriers tracing their ancestry to Friesland.

Summary Table

Both meanings connect to Friesland’s distinctive cultural and genetic legacy: one in symbolic

art, the other in hereditary health. If referring to medical risk within Frisian families, genetic

counseling and screening for the PLN mutation is recommended. If referring to symbolism, the “Frisian heart” represents historical pride rooted in centuries-old maritime identit

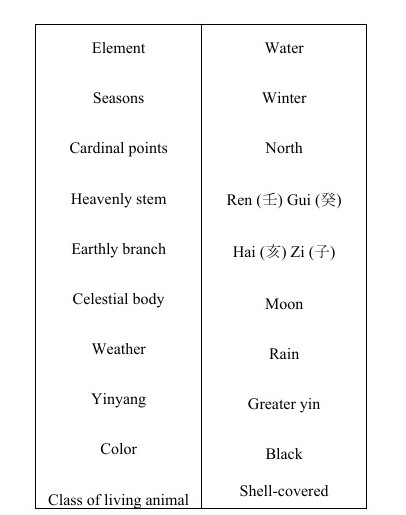

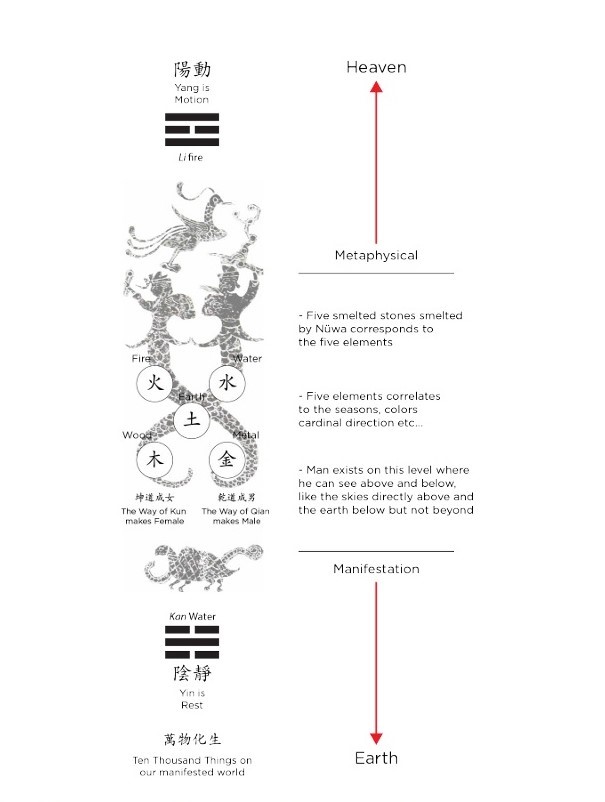

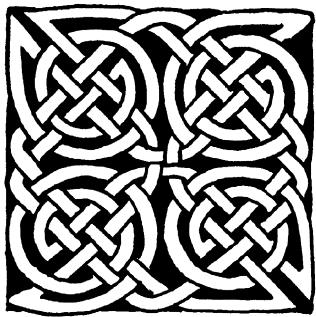

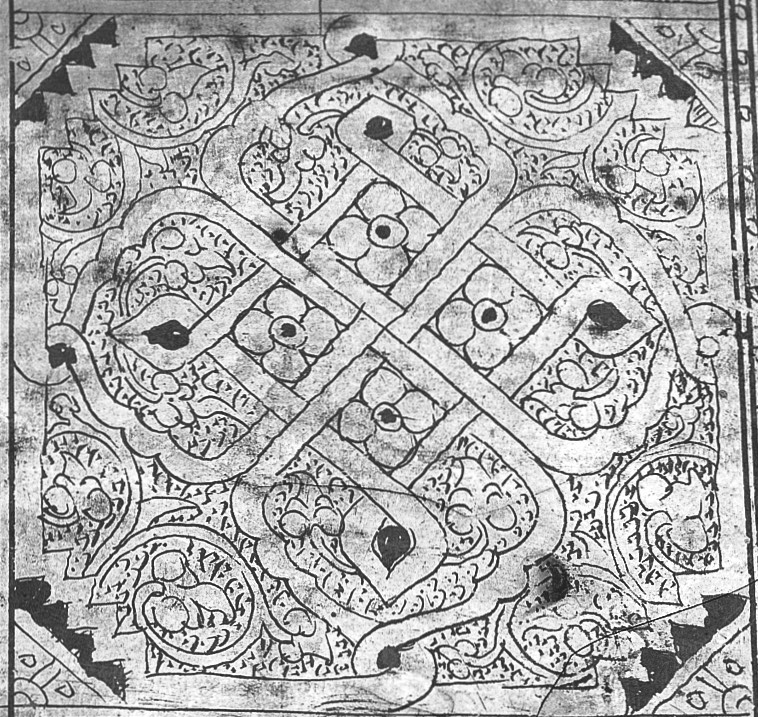

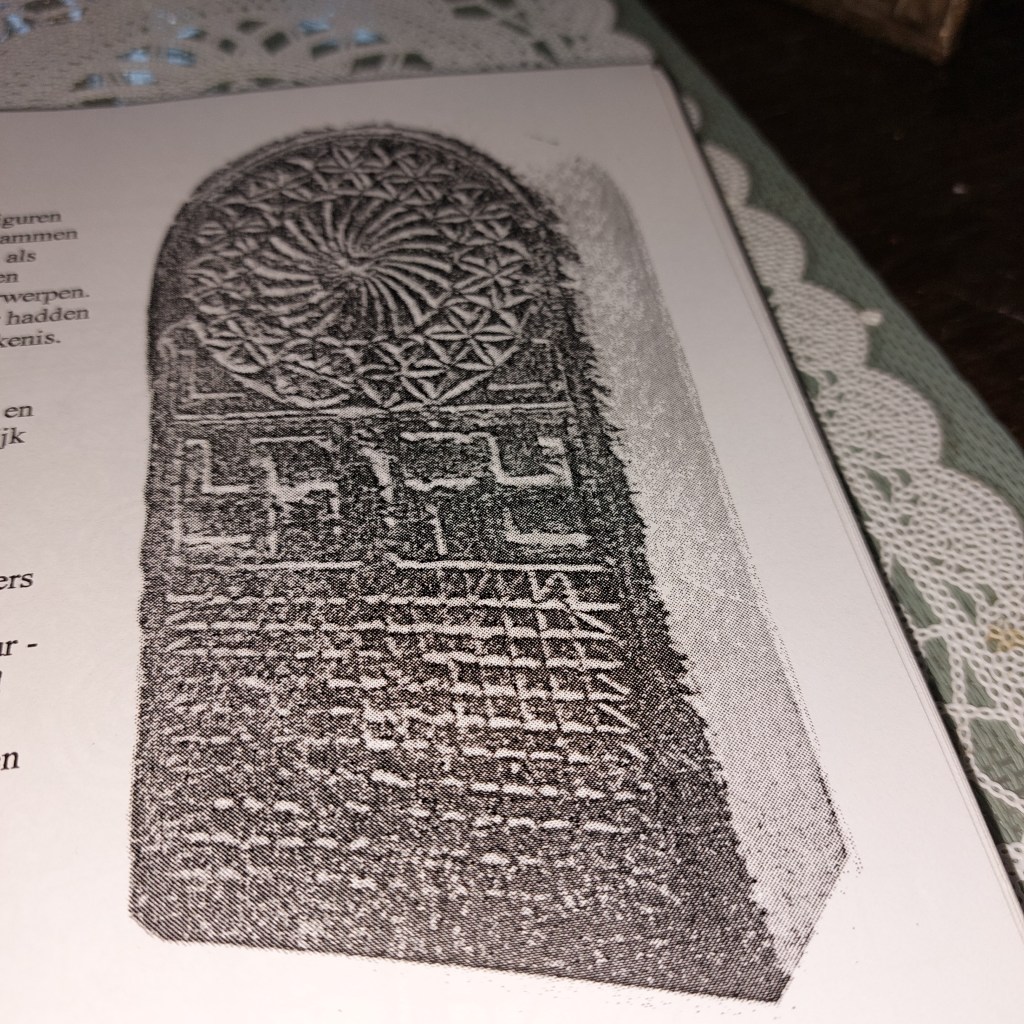

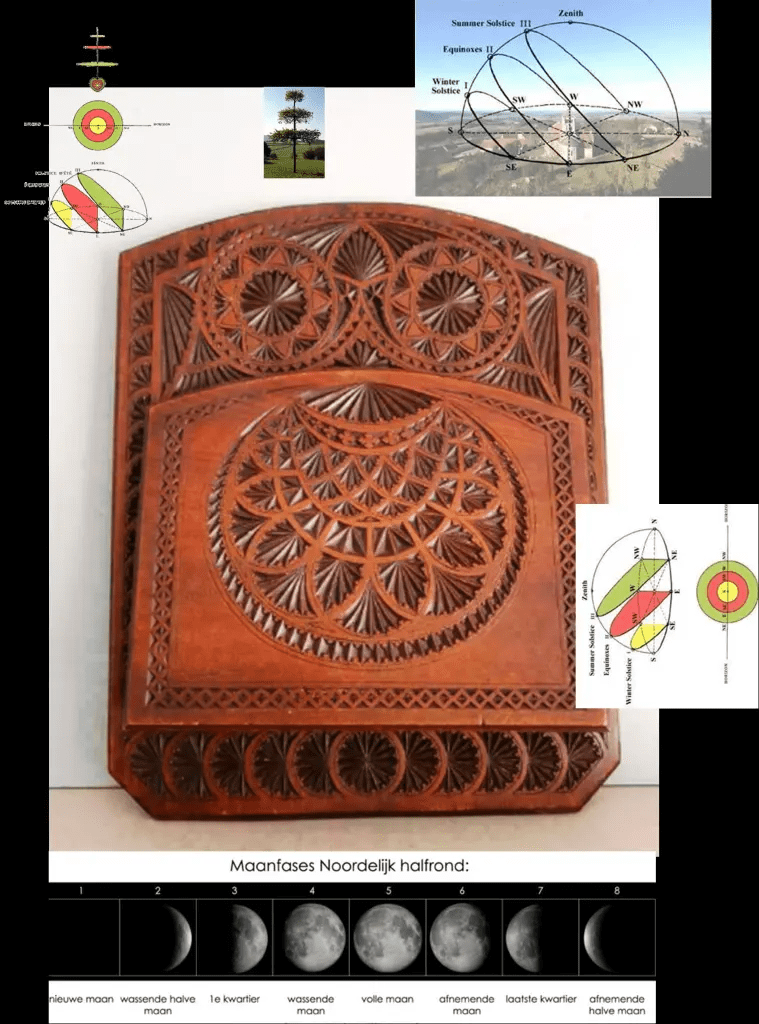

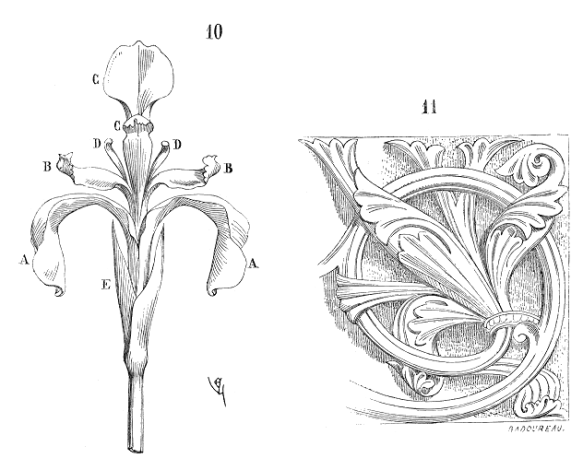

Origin and meaning of the Frisian pompeblêden

The Frisian pompeblêden—widely recognized as heart-shaped symbols on the flag of Friesland— actually represent stylized leaves of the yellow water lily native to the region, not hearts as often mistaken by outsiders

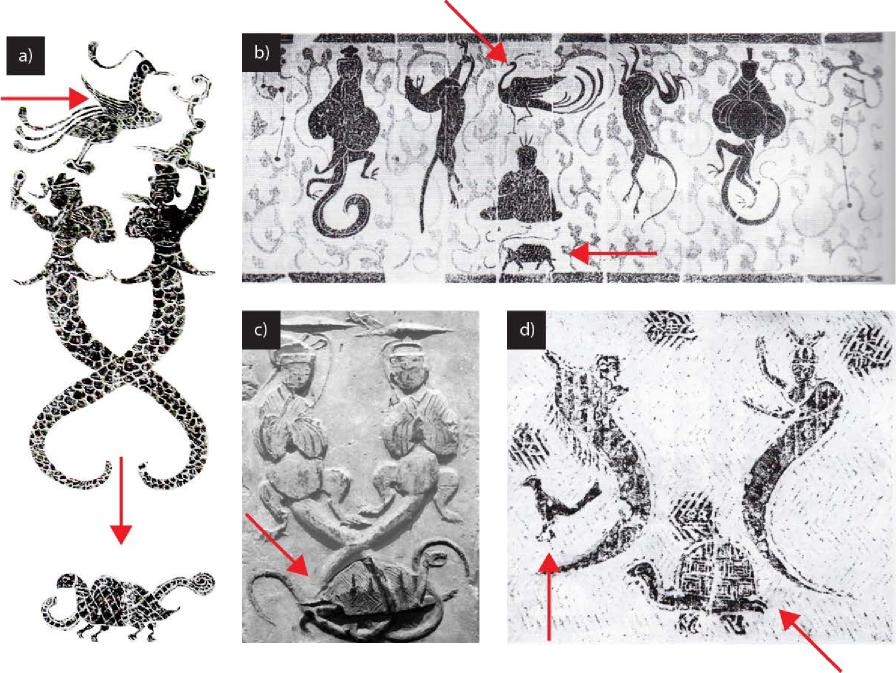

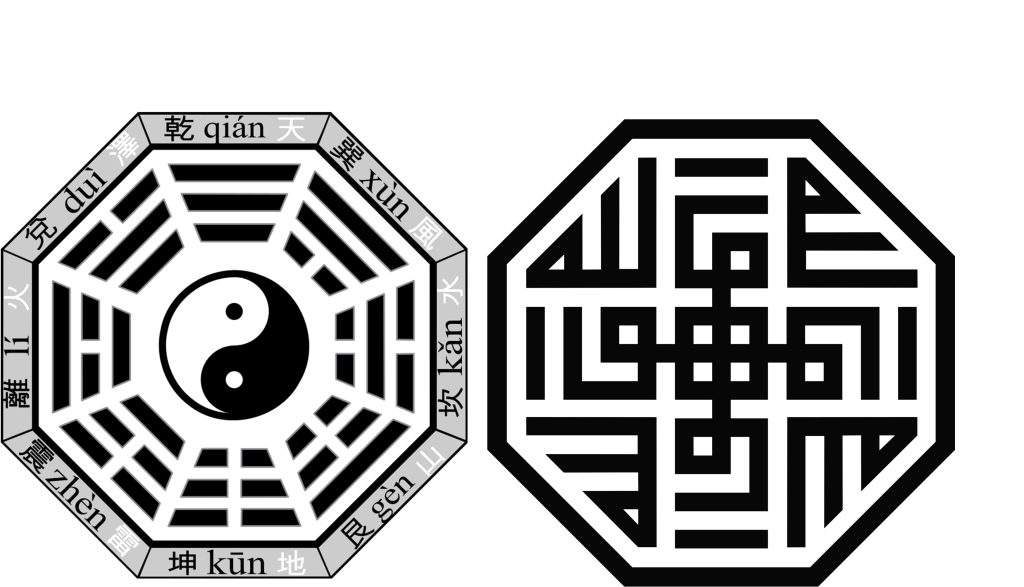

Apophis can also be fruitfully compared metaphorically with the heart, especially in symbolic and mythic terms relating to the struggle between order and chaos within the core of life and consciousness.

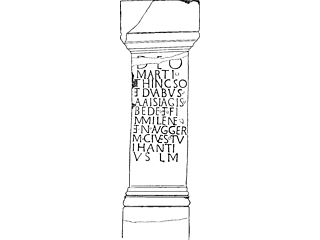

Origin

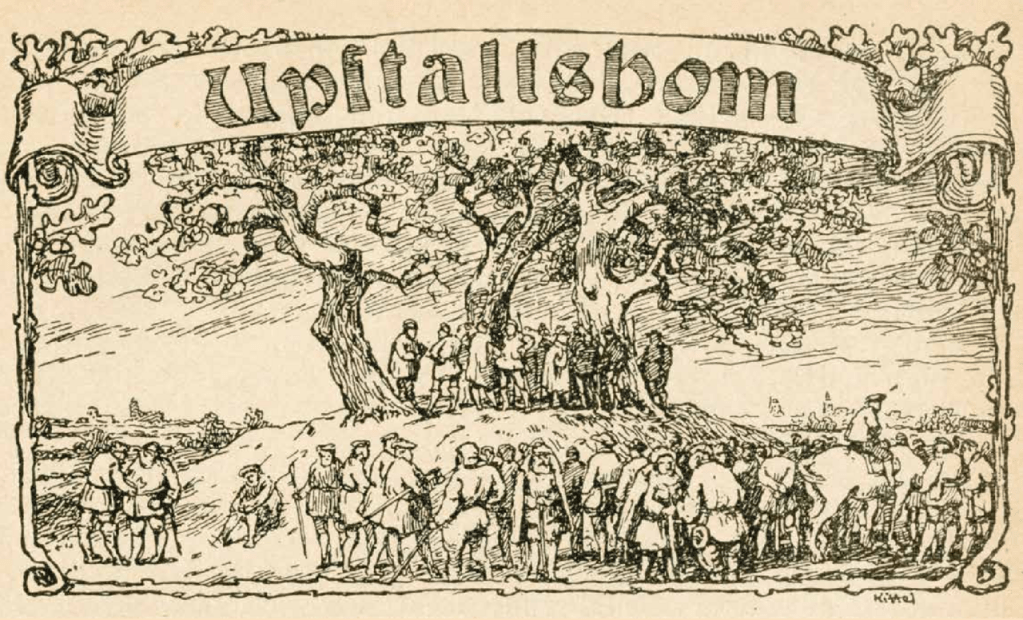

The tradition of using pompeblêden dates back at least to the Middle Ages. According to Frisian legend, the symbol originated with Friso, the legendary ancestor of the Frisians, who supposedly carried a weapon adorned with seven red leaves from the yellow water lily when settling the area.Medieval sources and heraldic documentation show the motif takes inspiration from coastal and maritime symbolism found in the Frisian region and neighboring parts of Scandinavia and Germany, most notably associated with water, lilies, and marshes. Early references can be found in epic poems and coats of arms from the 13th century, with Scandian and German cities using similar seeblatt (lake leaf) designs as the Fleur de Lys

.

Meaning

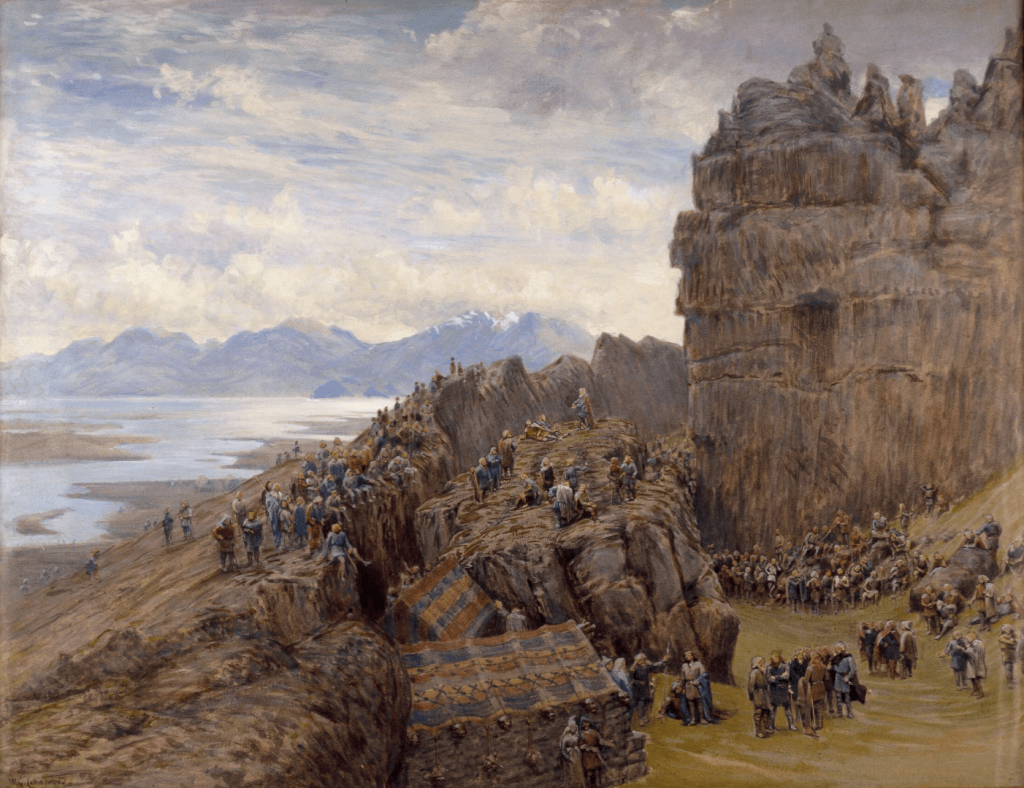

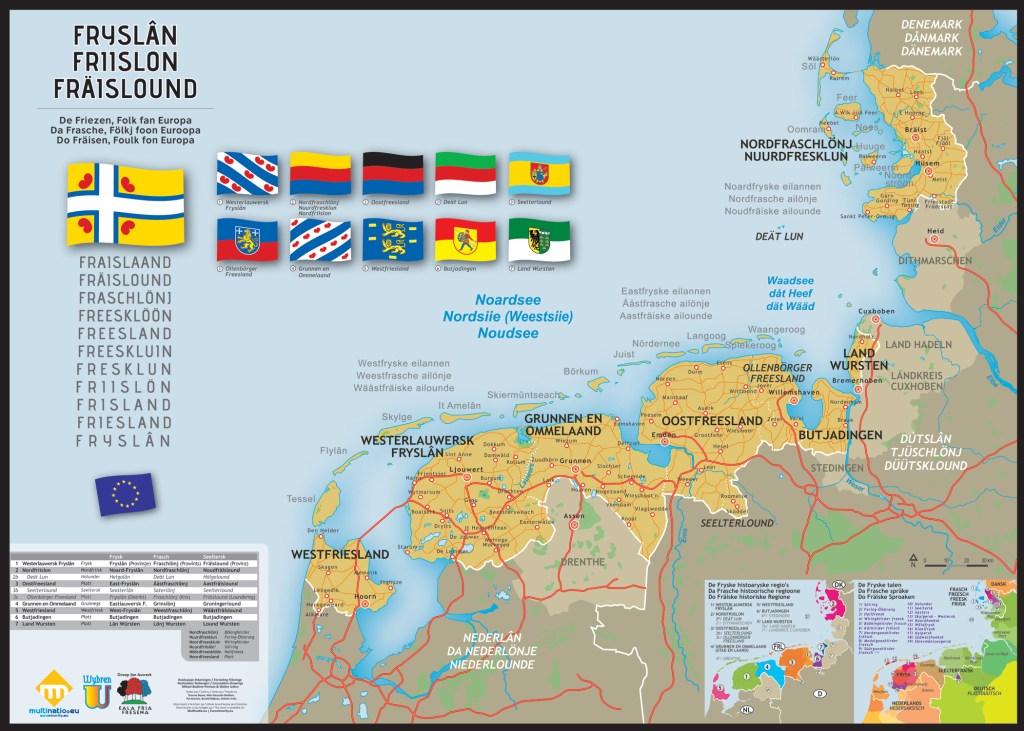

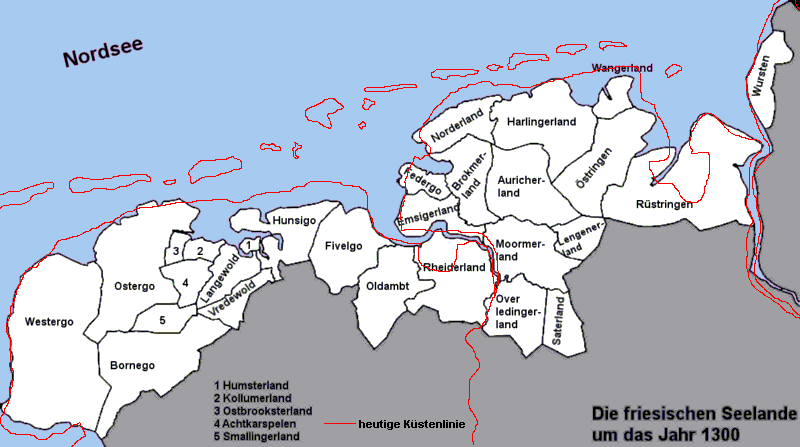

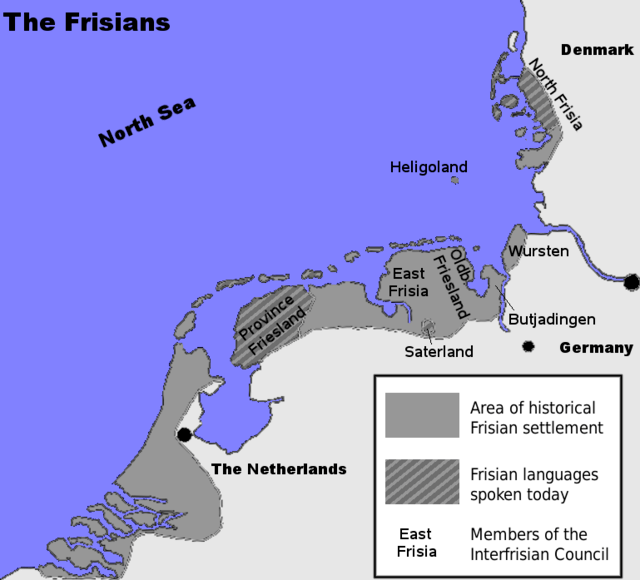

The seven pompeblêden on the flag refer symbolically to the “seven Frisian sea countries”:

independent territorial regions stretching from Alkmaar in the Netherlands to the Weser in

Germany, united historically in defense against external threats like the Vikings and Normans. While legend describes seven actual regions or the seven sons of Friso, historians note there may never have been exactly seven administrative units; in regional tradition, “seven” means “many” or “a large number”. The water lily leaves thus symbolize both the maritime nature of Friesland and its historical unity and autonomy across numerous independent districts.

- But outside that we have much more Traditional wisdom about it but totally ignored by he machine or modern universities:

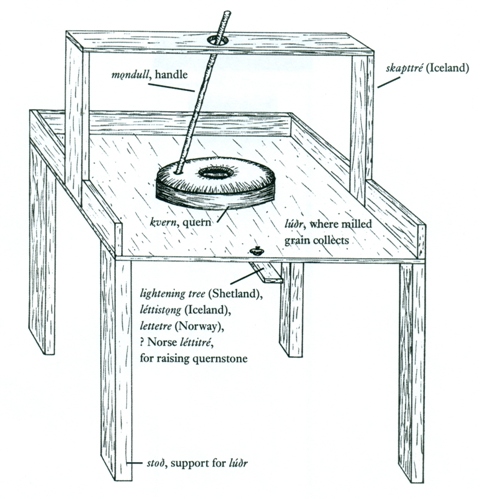

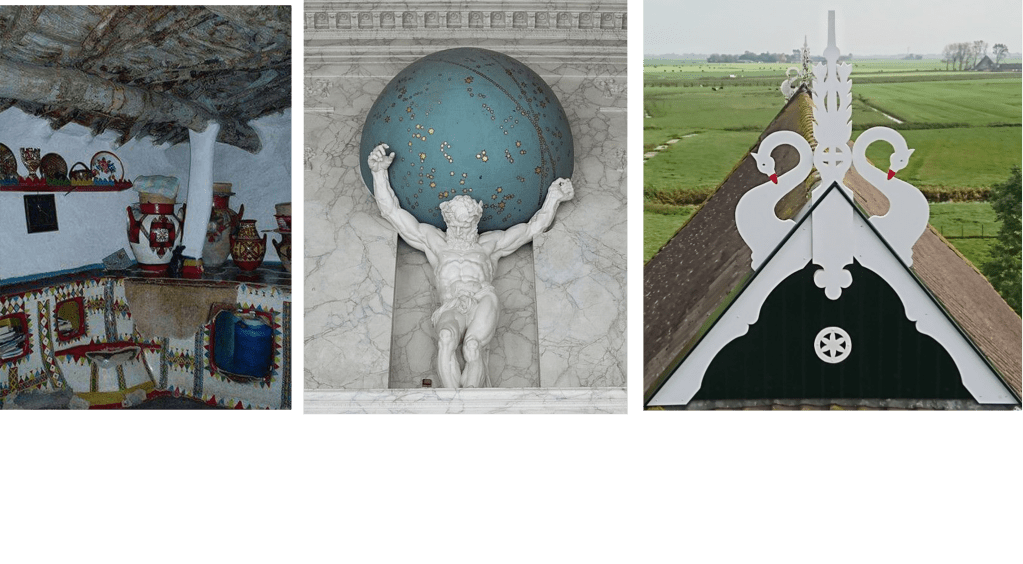

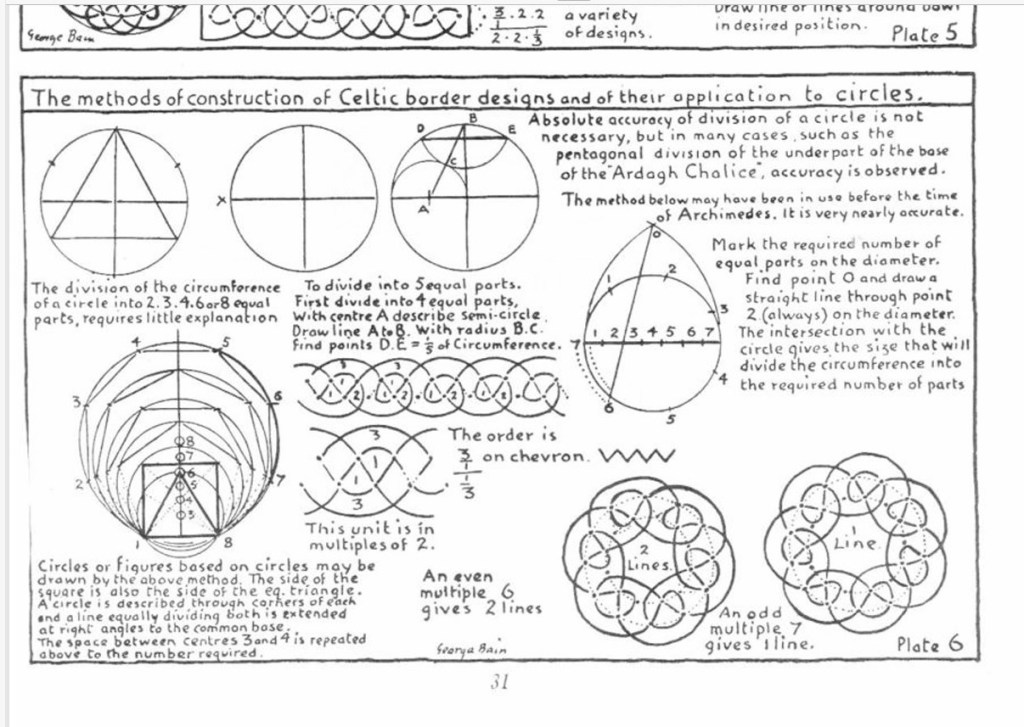

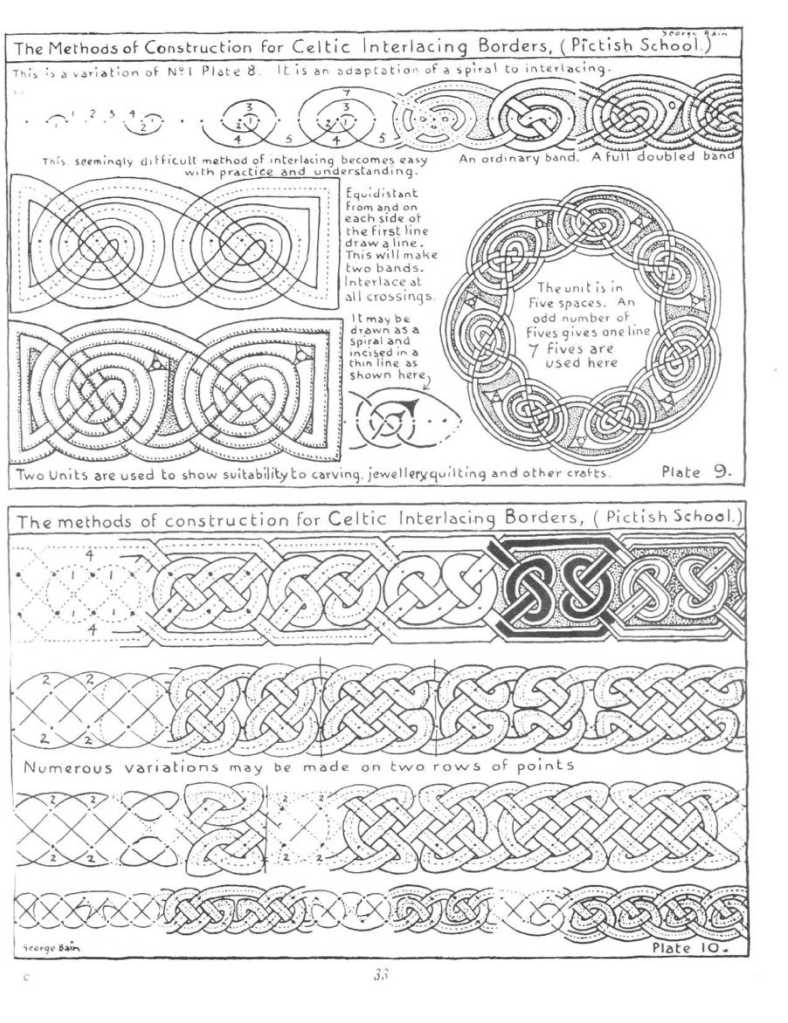

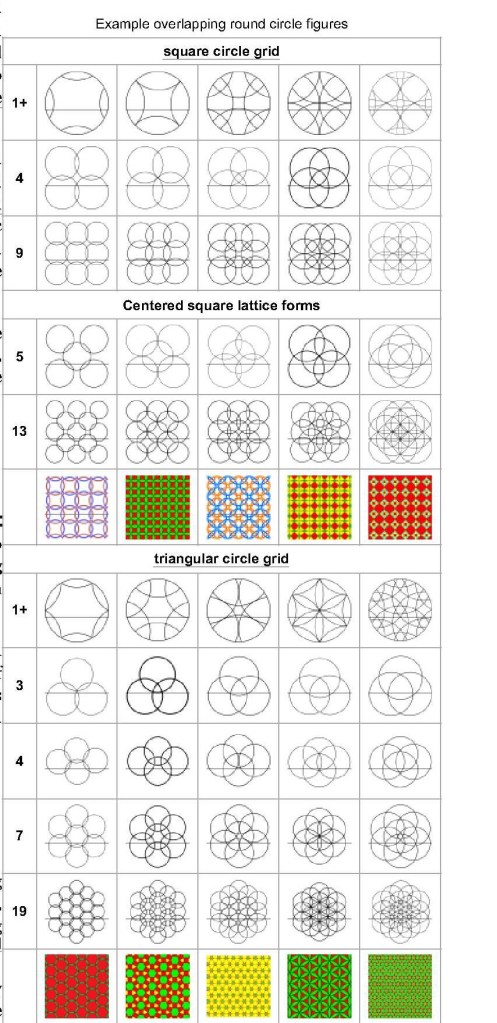

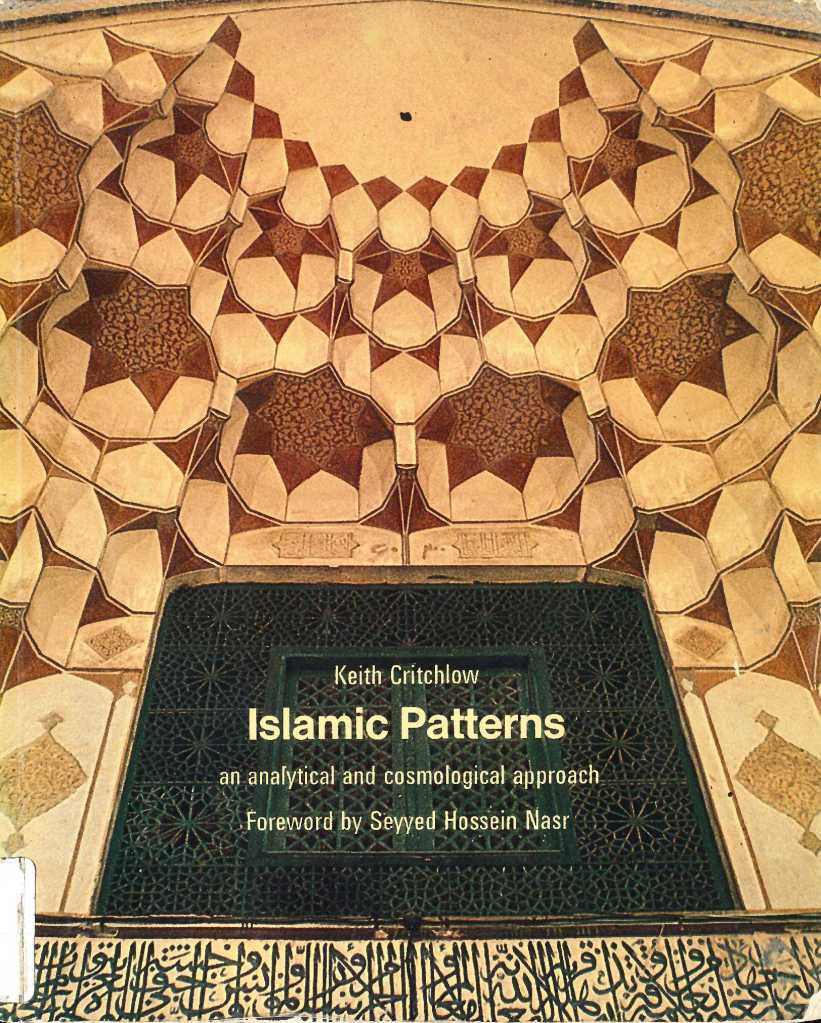

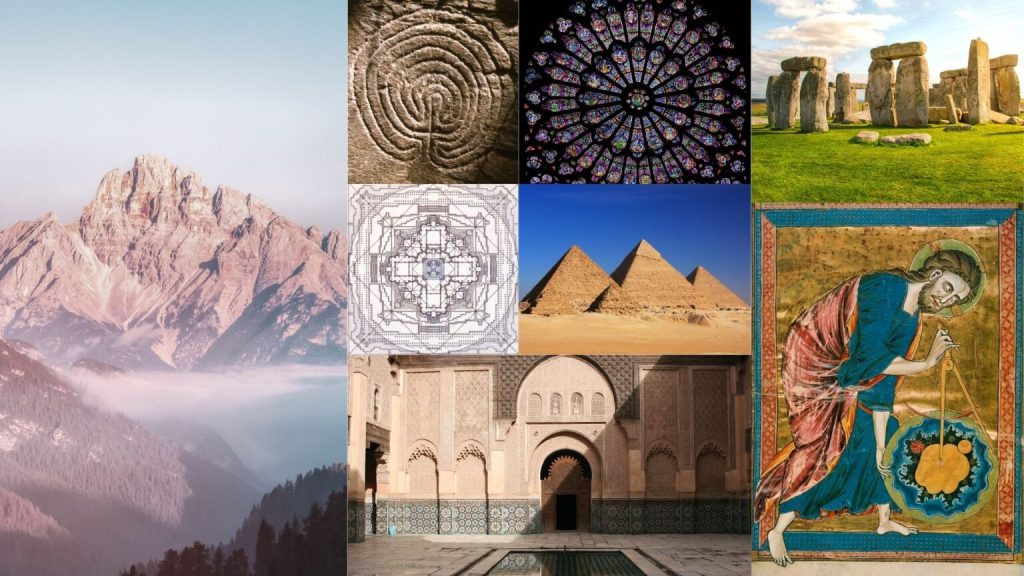

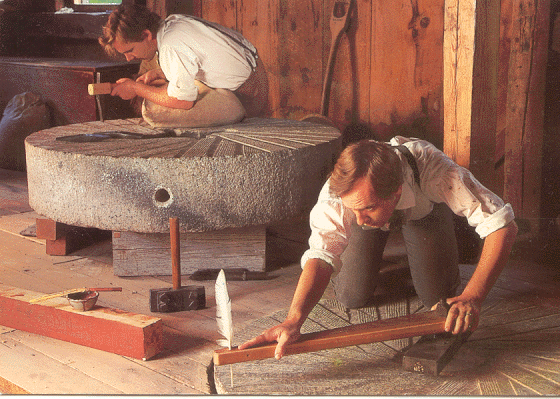

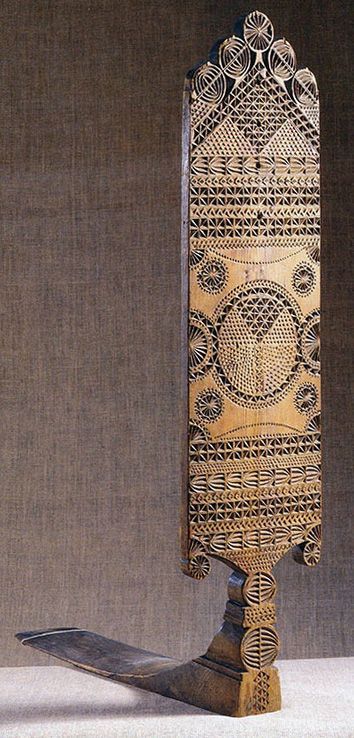

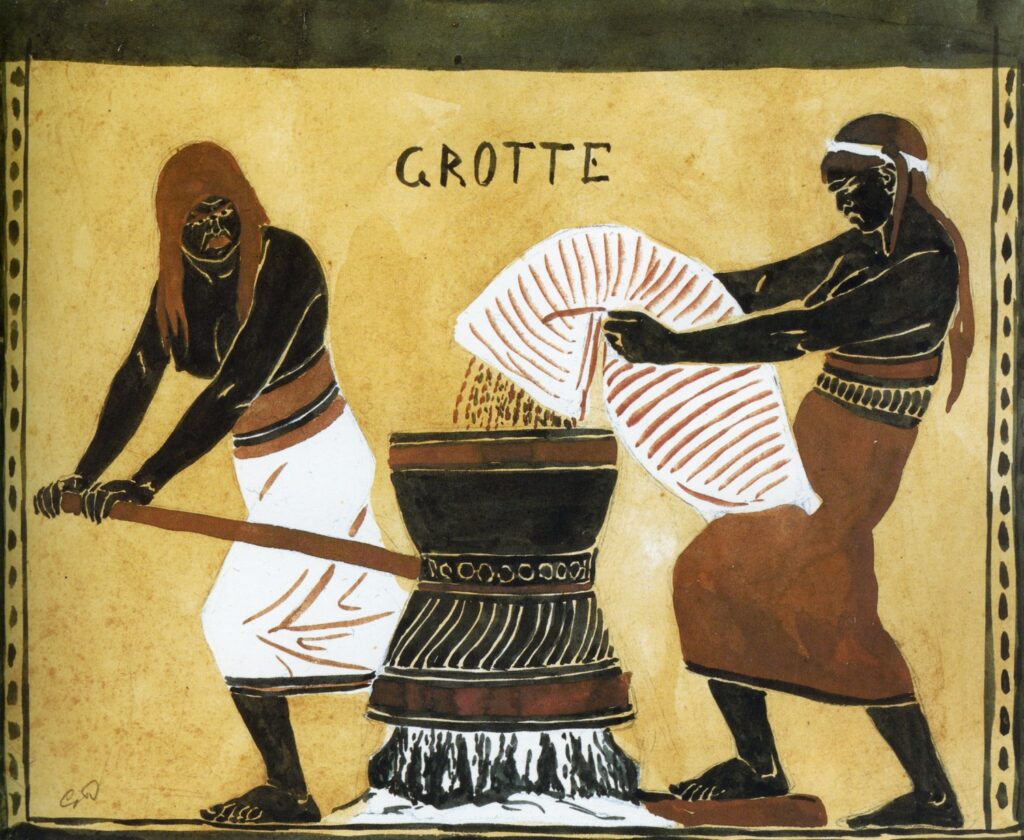

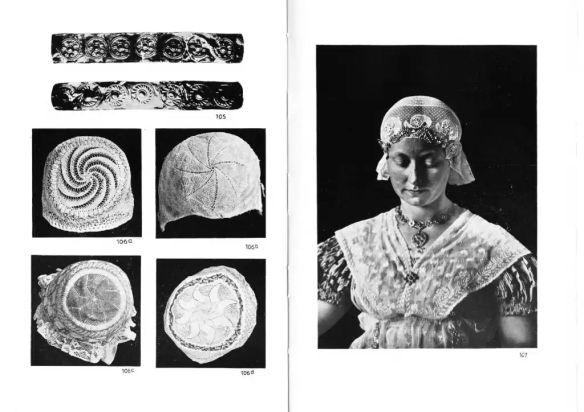

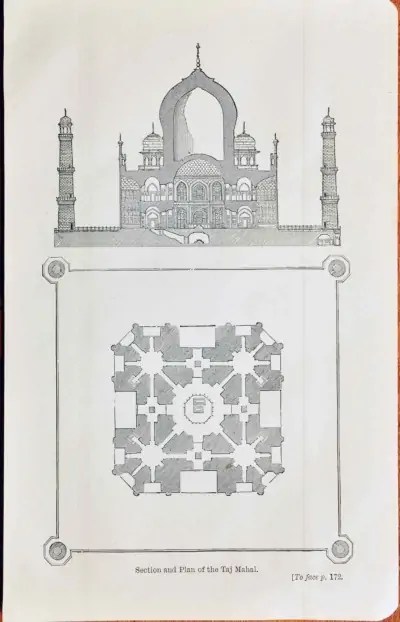

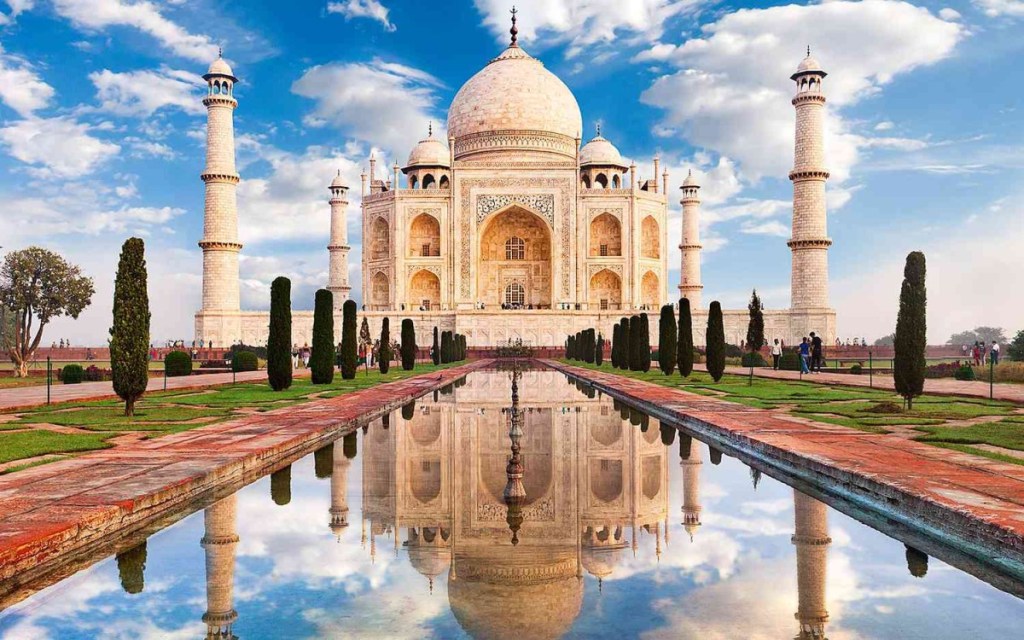

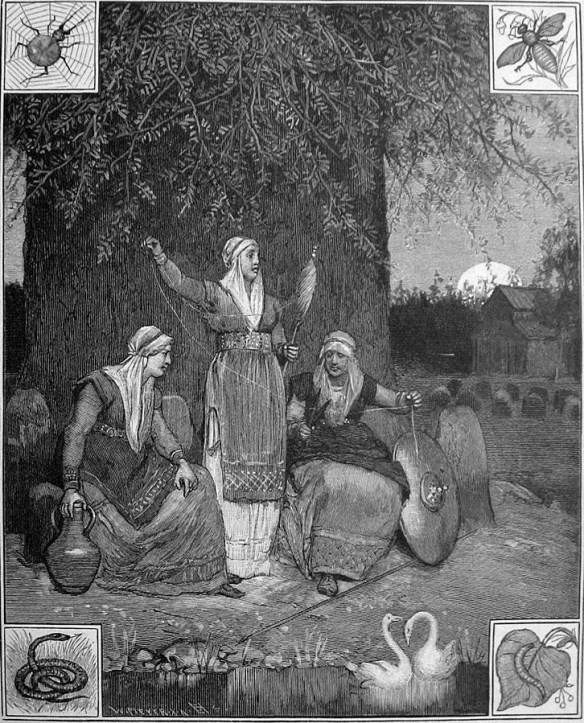

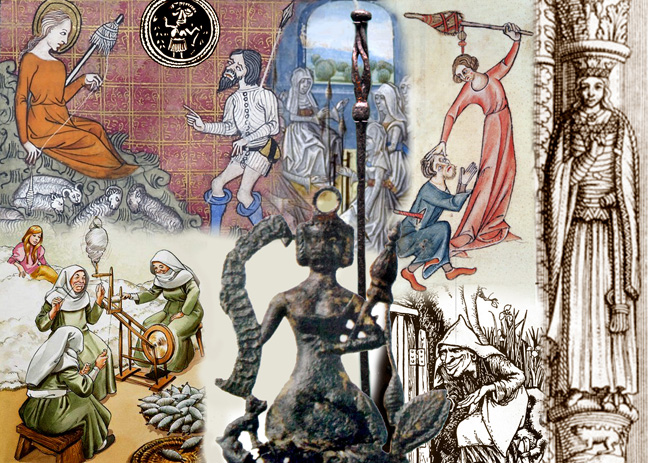

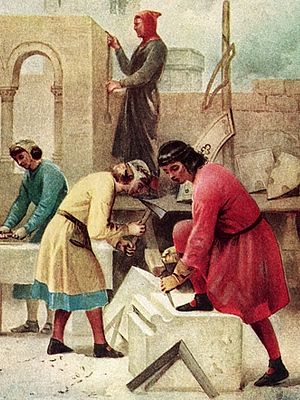

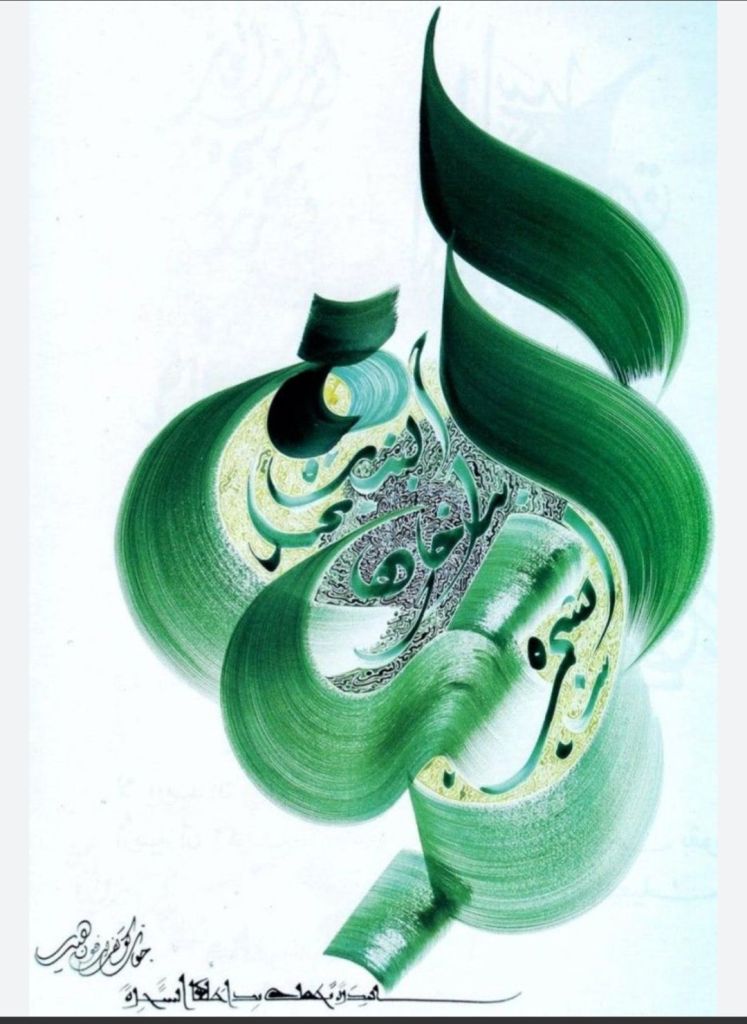

Craft as Sacred Knowledge

René Guénon viewed traditional craft not as utilitarian labor but as a means of cosmic participation. The traditional craftsman, for Guénon, was engaged in work that reflected the divine order:

“A craft is not merely a technique, but a transmission of a traditional knowledge, the application of principles that are ultimately metaphysical.”

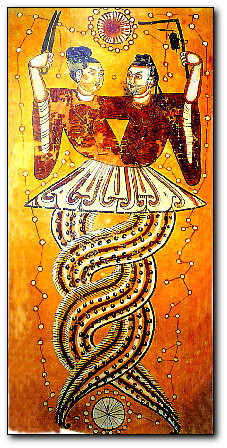

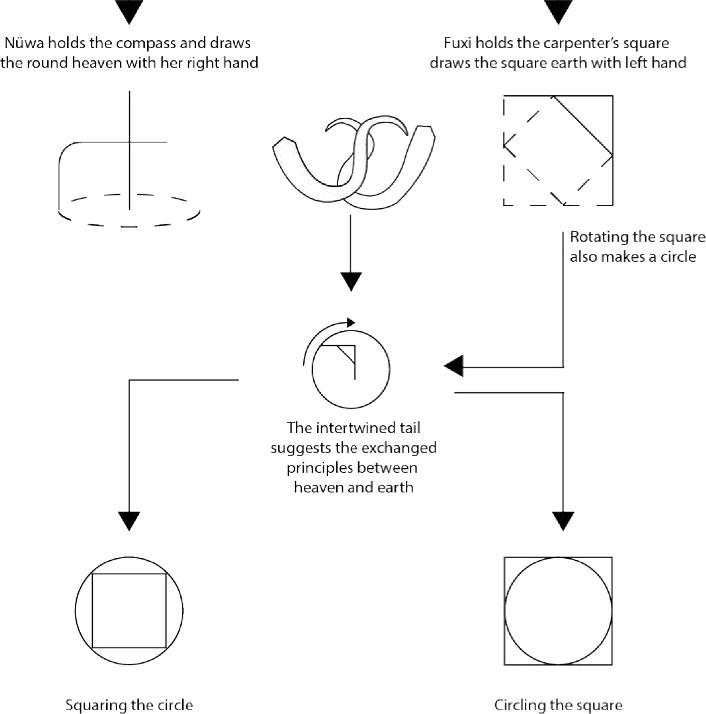

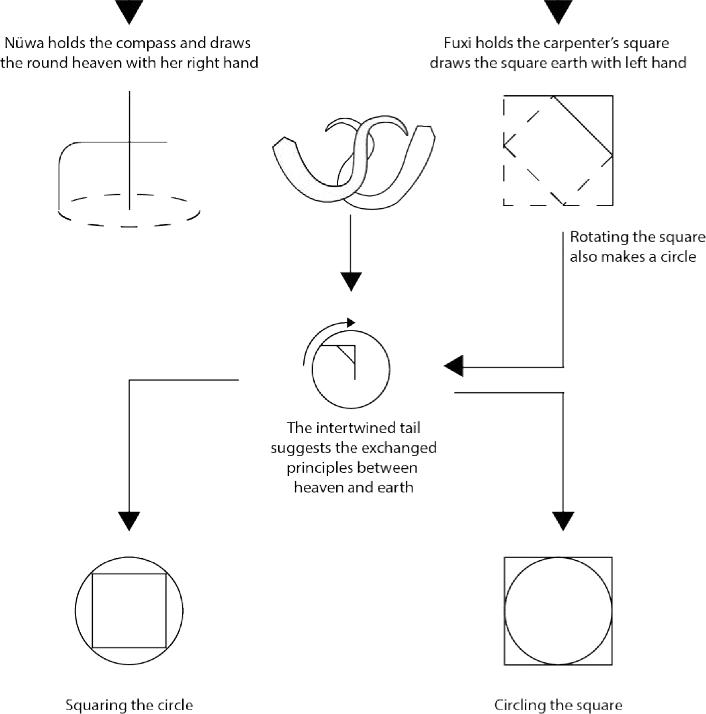

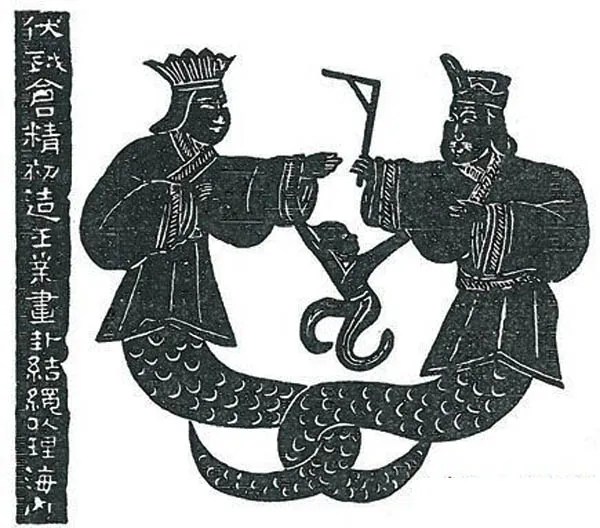

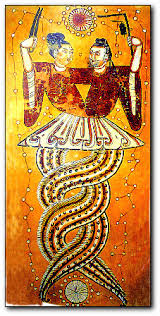

In traditional civilizations, there was no division between the sacred and the secular in labor. Every craft, from carpentry to stonemasonry, was infused with symbolic meaning. The tools themselves—like the compass, the square, or the chisel—served as metaphors for universal truths. The craftsman, through repeated and intentional action, participated in the divine act of creation.

Work and contemplation were not separate in traditional societies. A craftsman worked not just with his hands but also with an awareness of the symbolic and spiritual meaning of his work.

The tool, the material, and the process had symbolic dimensions. For instance, in masonry or metalwork, the transformation of raw material symbolized the transformation of the soul.

Initiation and Guilds

Guénon emphasized the role of initiatic craft guilds—especially in the West, such as medieval masonry guilds—which preserved esoteric teachings and transmitted initiatic knowledge through symbols, rituals, and oral transmission.

These guilds were structured hierarchically and transmitted cosmological knowledge embedded in tools, geometry, architecture, and ritual.

The compass and square, for example, symbolized heaven and earth or spirit and matter.

The architecture of temples or cathedrals followed sacred geometry, aligning physical structures with cosmic principles.

Degeneration in Modernity

Guénon argued that in modern times, the loss of sacred and symbolic understanding has led to the degeneration of crafts into mere technical skills, disconnected from their metaphysical roots.

This reflects his larger thesis: modernity is a descent into materialism, fragmentation, and loss of spiritual orientation””. The disappearance of guilds, desacralization of labor, and mass industrialization exemplify this decline.

Read Here: The Arts and their Traditional Conception

Art That Expresses Truth

Ananda Coomaraswamy, deeply rooted in both Eastern and Western traditions, emphasized that the traditional artist or craftsman was not creating to express individuality, but to reveal the timeless: “The traditional craftsman did not ‘express himself,’ he expressed truths.”

Coomaraswamy rejected the modern cult of originality and innovation. For him, traditional art and craft were “vehicles for eternal wisdom“. The form was not arbitrary—it was a symbolic expression of metaphysical principles, passed down through sacred traditions. Every detail, from proportions to ornamentation, had a purpose that reached beyond aesthetics.

“Work is for the sake of the work done, and not for the profit therefrom.”

In this sense, “work was prayer “—a form of contemplation, a discipline of the soul.

Read here: Primitive Mentality: The myth is not my own, I had it from my mother.

Beauty as a Path to the Divine

Frithjof Schuon* extended these insights by focusing on the spiritual essence of traditional art. For Schuon, beauty itself was a reflection of the Divine:

“The beauty of a traditional object reflects the eternal archetypes; it speaks in silence to the soul.”

Craftsmanship, when aligned with traditional forms, becomes a contemplative path. Whether it’s a sacred icon, a hand-carved door, or a woven textile, its power lies in its “participation in the eternal “. For Schuon, even in a world that has largely lost its traditional frameworks, the sacred can still be accessed through ” form, beauty, and right intention:

“A sacred form, however simple, is a vessel of grace.”

A Living Tradition

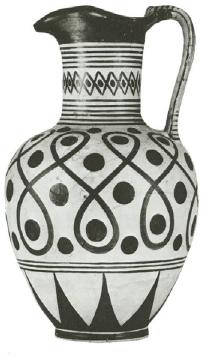

What unites Guénon, Coomaraswamy, and Schuon is the belief that “”true craft is never arbitrary”. It arises within a living tradition, where every gesture, pattern, and proportion reflects a metaphysical reality. In contrast, modern craftsmanship—stripped of symbolism and spiritual orientation—becomes hollow, reduced to commerce or self-expression.

Their critique is not simply nostalgic. It is a call to recover the sacred dimension of human making—to reintegrate craft into a vision of life that is oriented toward the transcendent.

To make with the hands, in the traditional sense, is to align oneself with the cosmos. Craft, then, becomes more than labor—it becomes liturgy. The Traditionalist vision invites us to see again with sacred eyes: to recognize that a pot, a wall, a song, or a loom, when shaped by truth and beauty, can become a path toward the eternal.

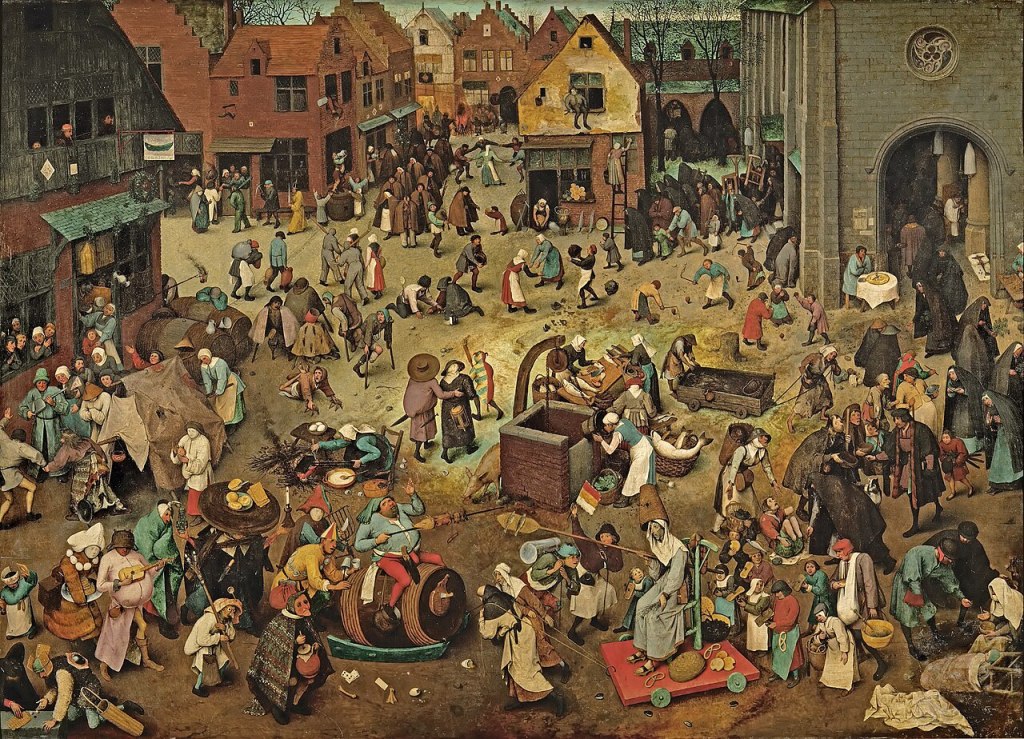

Made for use versus made for sale, creation versus production. Human being valued versus machine being valued.. When the human being is valued, there is integrity in the work. There is dignity in the freedom to work for purpose, and satisfaction knowing the effort is respected. When the human being is removed from the actual creation or building of the thing itself, the spirit of the work, whatever it is, is disconnected if not all together removed making the being servile to the method of production.

The ‘maker’ thus becomes a salesperson for something they have had manufactured for them to sell as their own to make an individual profit. The purpose is then not the benefit or betterment of humanity, but the betterment and advancement of oneself. And this

form applies now to almost all forms of artistic creation be it painting, dance, music, fashion,

design, architecture, interior design and so on; they all have become templated ideas easily

reproduced without much prerequisite of fundamental knowledge or originality.

–Finding Harmony: A King’s Vision

Our Royal Founding President, His Majesty The King, will be featured in a new documentary exploring his lifelong commitment to the environment. The documentary will launch globally on Prime Video on 6 February 2026.

The principles of Harmony, explored in the documentary Finding Harmony, have long been central to the mission of the School of Traditional Arts. They form the core values that underpin every aspect of our work, grounded in the understanding that we are part of nature and that everything we create must exist in harmony with the natural order.

This awareness is practised through the discipline of craftsmanship—a discipline that nurtures a balanced relationship between the head, the heart, and the hand. In this way, the documentary reflects not only His Majesty’s vision, but also the enduring ethos that guides our teaching and practice.

Read here: Why Exhibit Works of Art?

For more info about Craft and Sacred Architecture read:

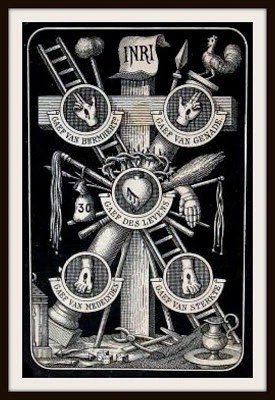

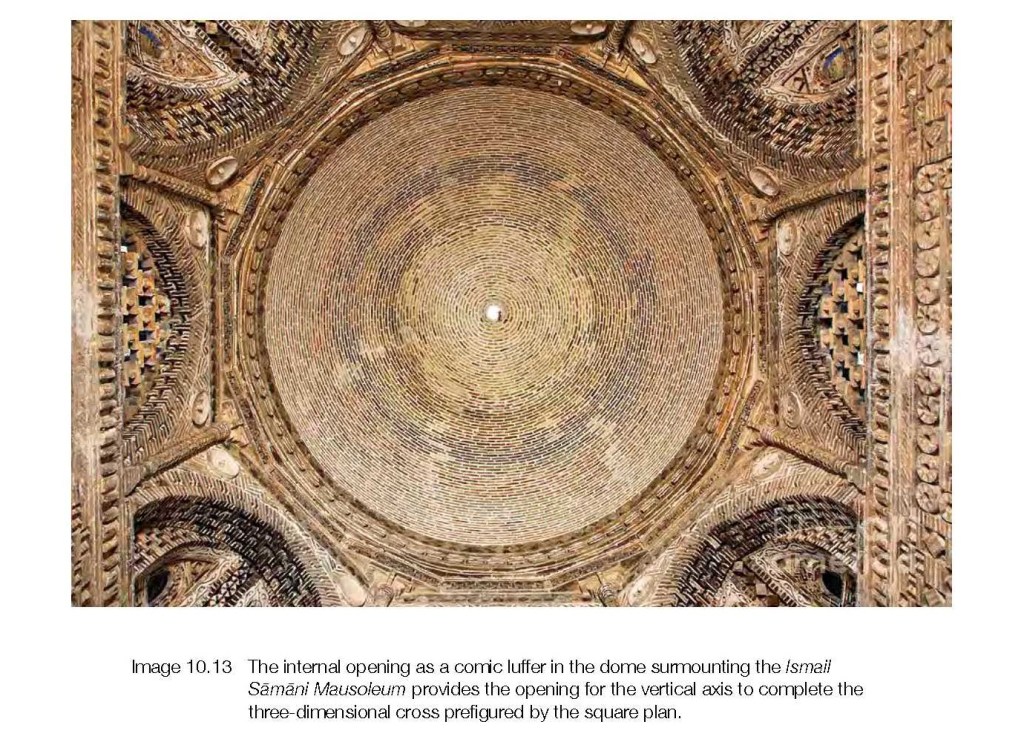

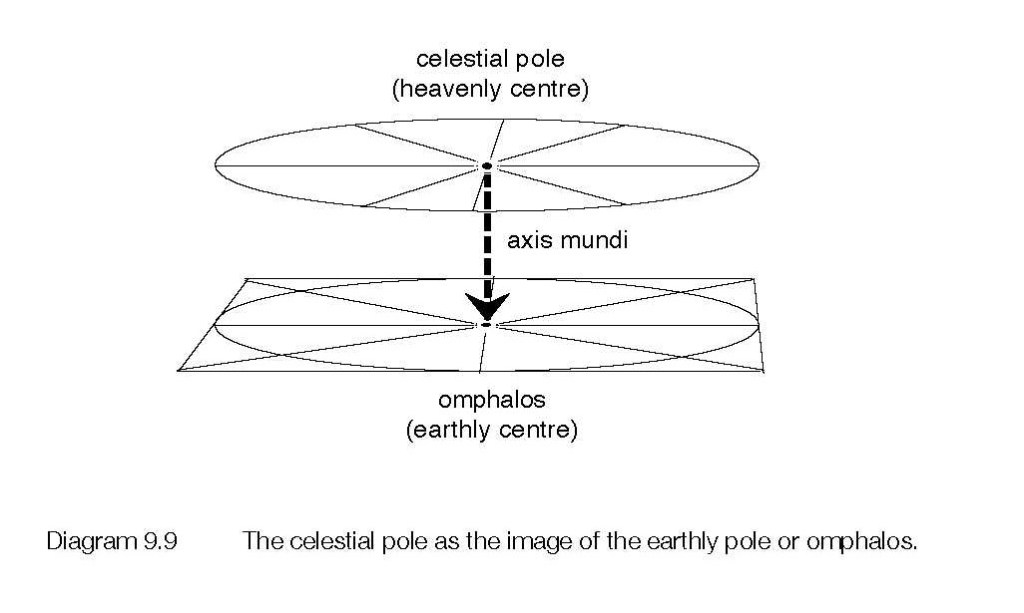

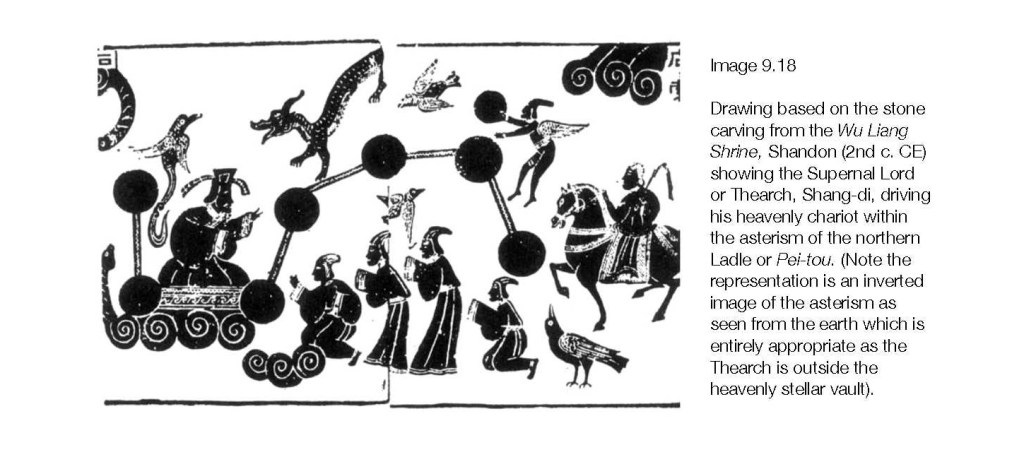

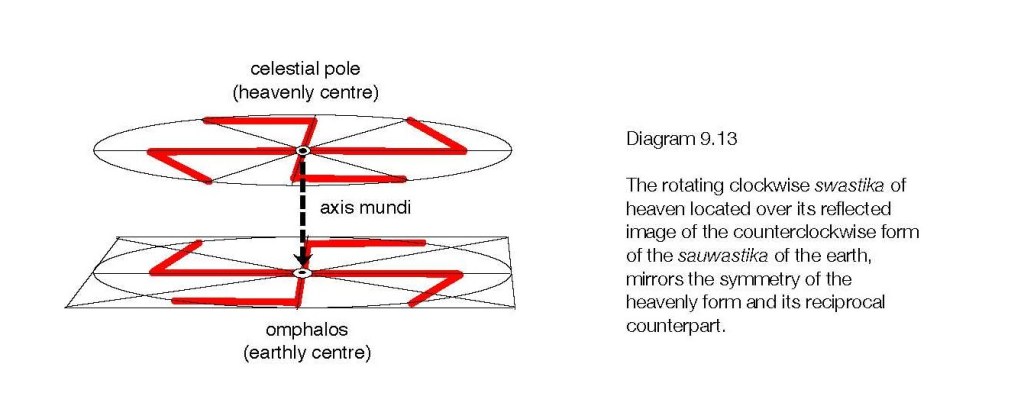

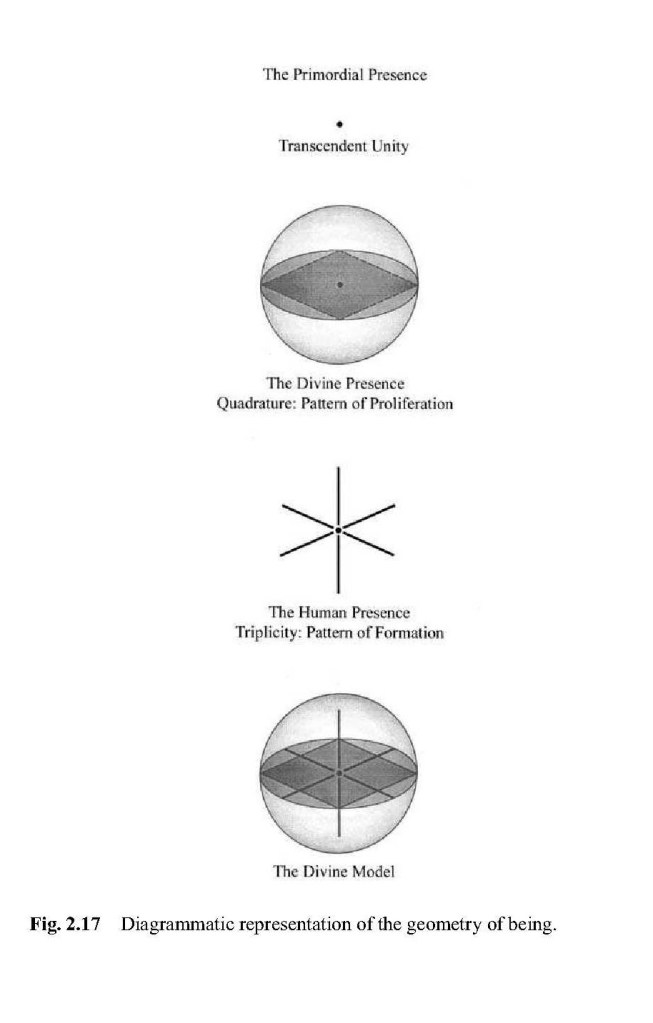

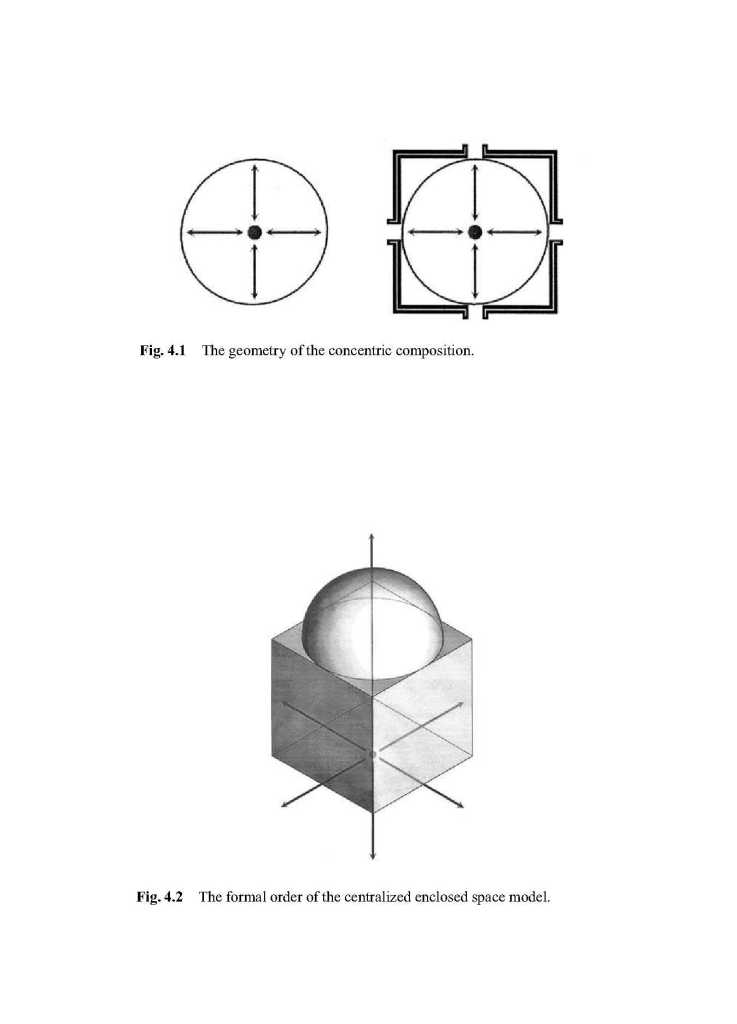

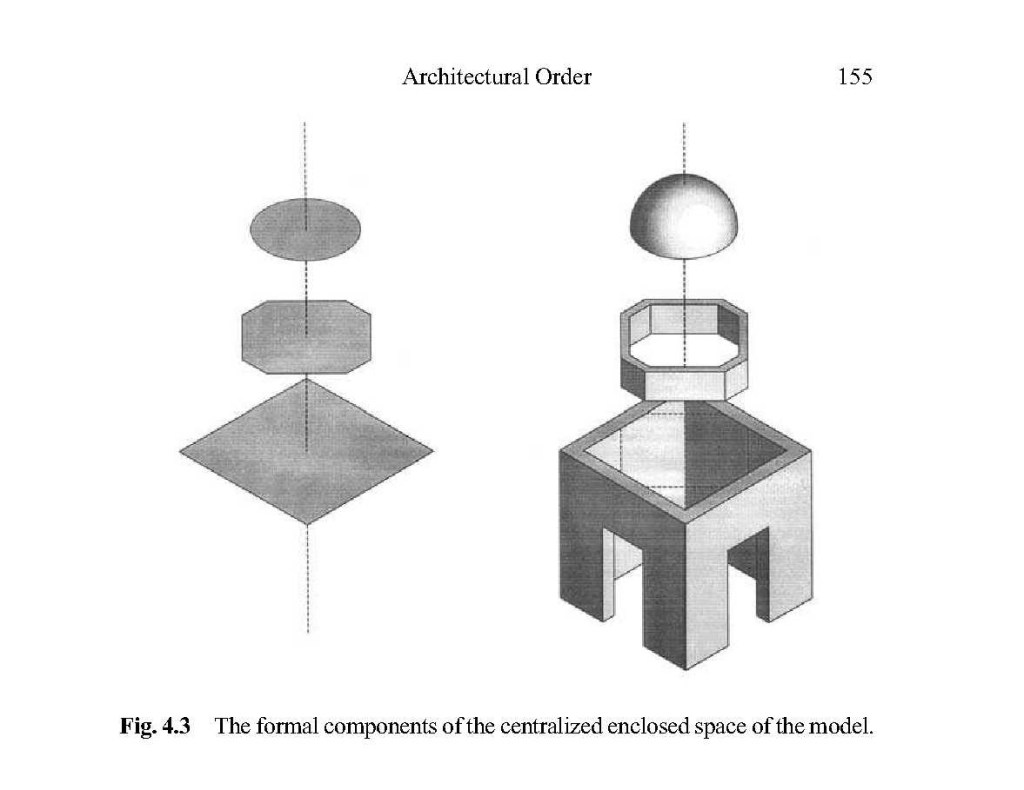

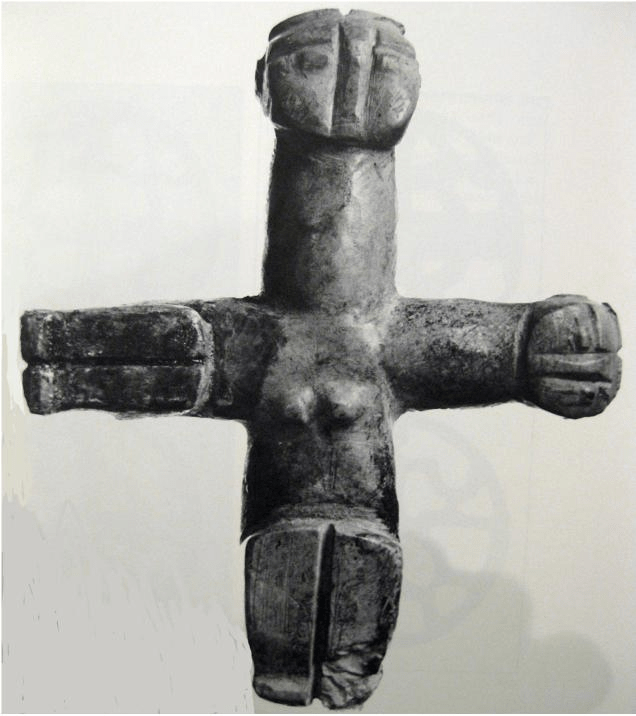

An Hermeneutic Exploration of René Guénon’s Symbolism of the Cross Applied to Sacred Architecture.

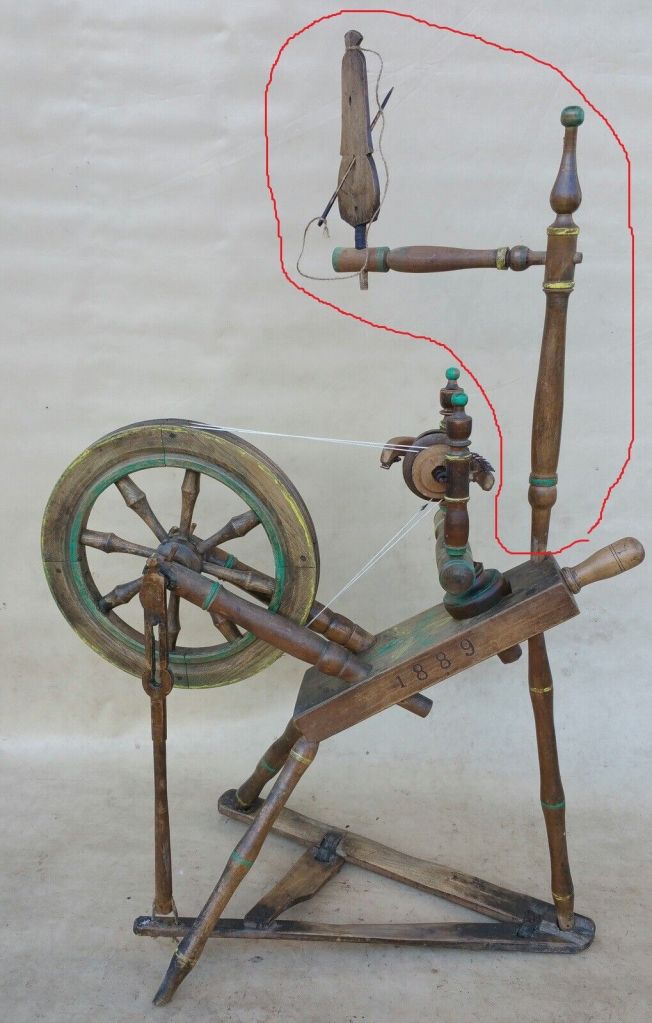

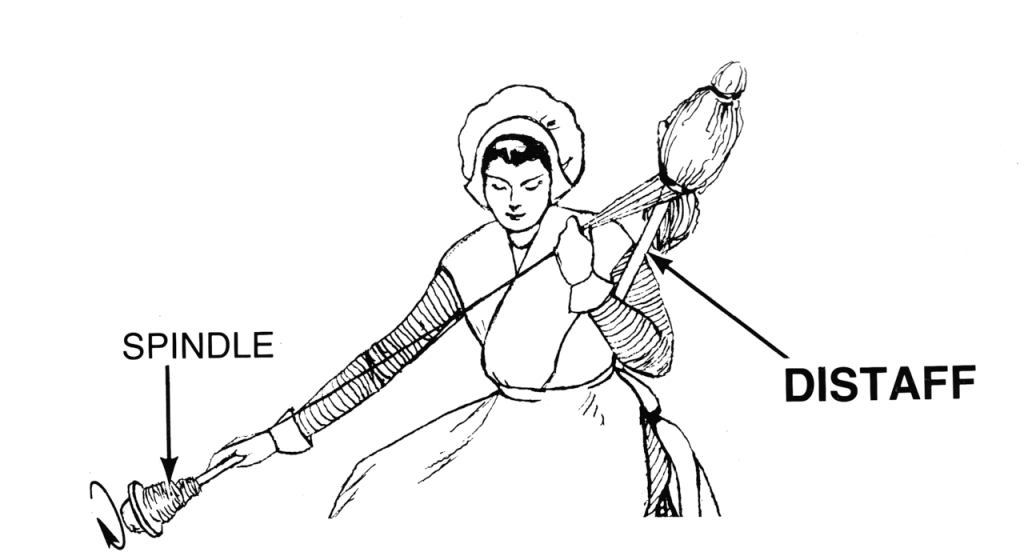

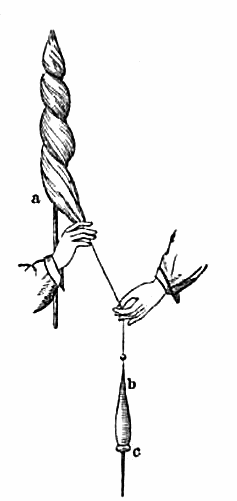

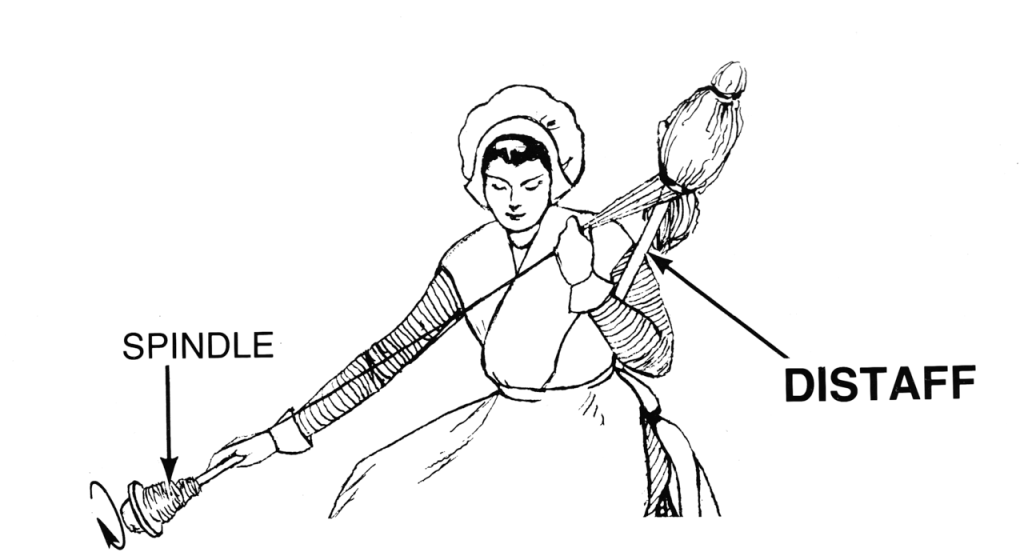

The Thread-Spirit Doctrine:An Ancient Metaphor in Religion and Metaphysics with

Prehistoric Roots

The Essential Titus Burckhardt: Reflections on Sacred Art, Faiths, and Civilizations

Cosmology_and_architecture_in_premodern Islam

Buildings Without Architects:

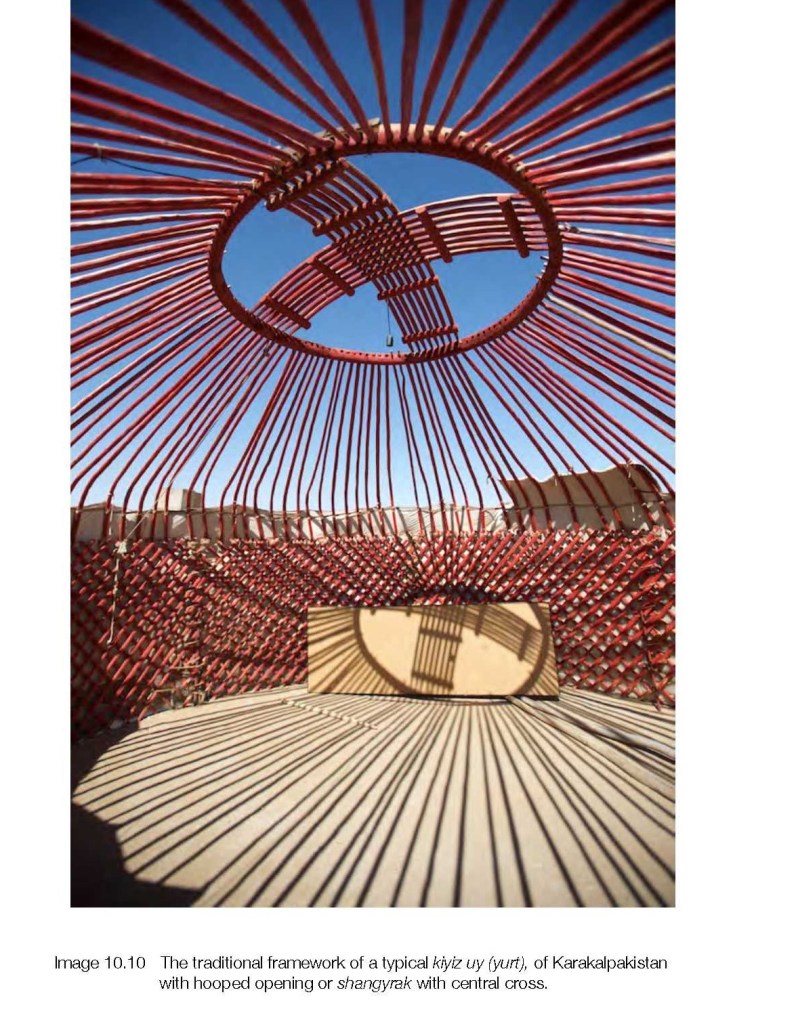

Buildings Without Architects is a wonderfully informative reference on vernacular styles, from adobe pueblos and Pennsylvania barns to Mongolian gers and European wooden churches. This small but comprehensive book documents the rich cultural past of vernacular building styles. It offers inspiration for home woodworking enthusiasts as well as architects, conservationists, and anyone interested in energy-efficient building and sustainability.

The variety and ingenuity of the world’s vernacular building traditions are richly illustrated, and the materials and techniques are explored. With examples from every continent, the book documents the diverse methods people have used to create shelter from locally available natural materials, and shows the impressively handmade finished products through diagrams, cross-sections, and photographs. Unlike modern buildings that rely on industrially produced materials and specialized tools and techniques, the everyday architecture featured here represents a rapidly disappearing genre of handcrafted and beautifully composed structures that are irretrievably “of their place.” These structures are the work of unsung and often anonymous builders that combine artistic beauty, practical form, and necessity. Read Here

==================

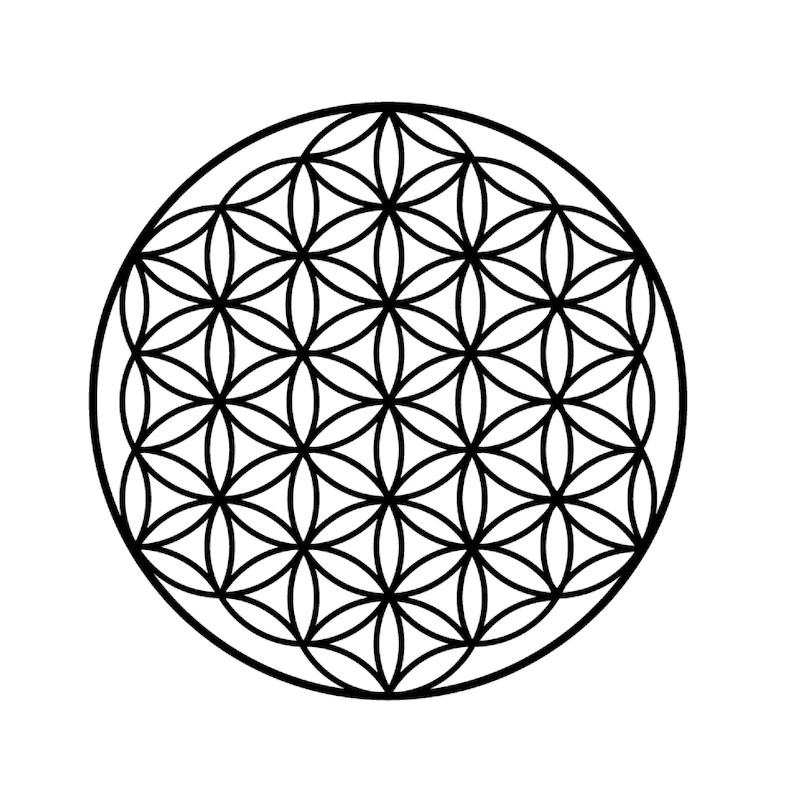

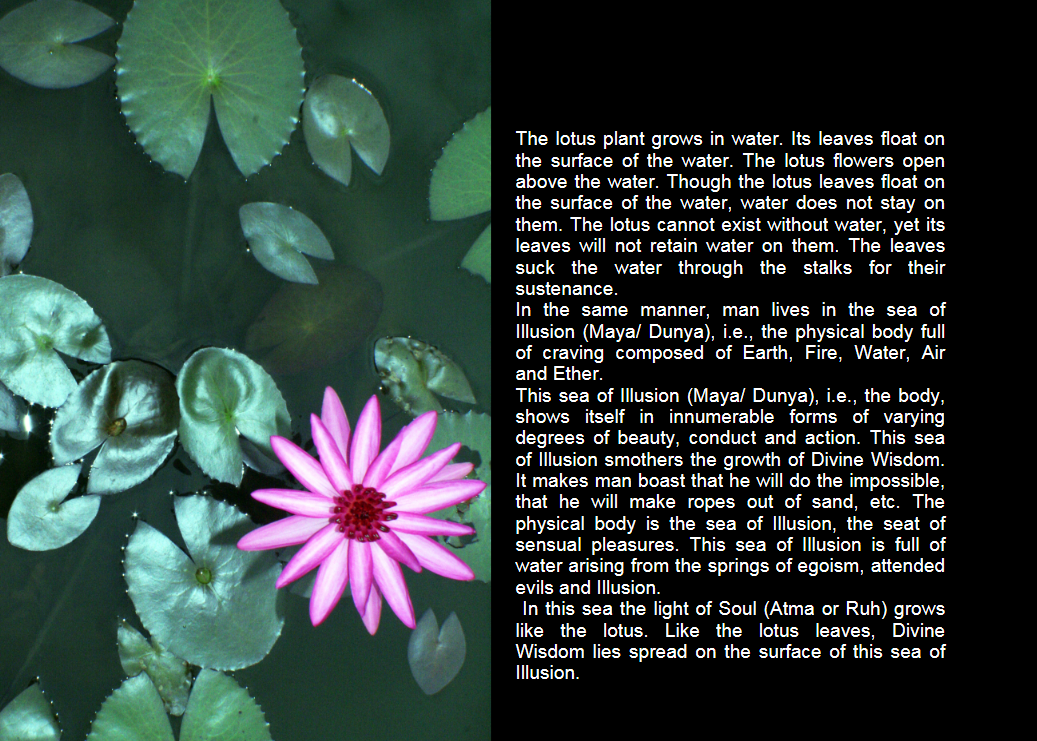

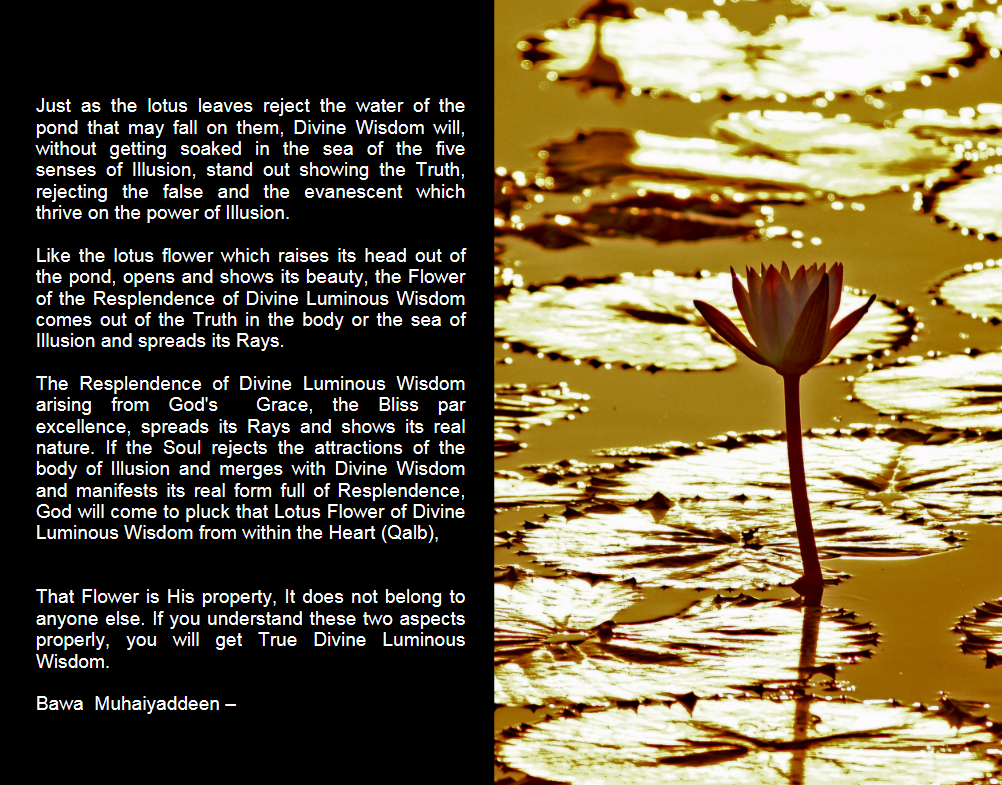

That Flower is His property, It does not belong to anyone else. If you understand these two aspects properly, you will get True Divine Luminous Wisdom,

Bawa Muhaiyaddeen —

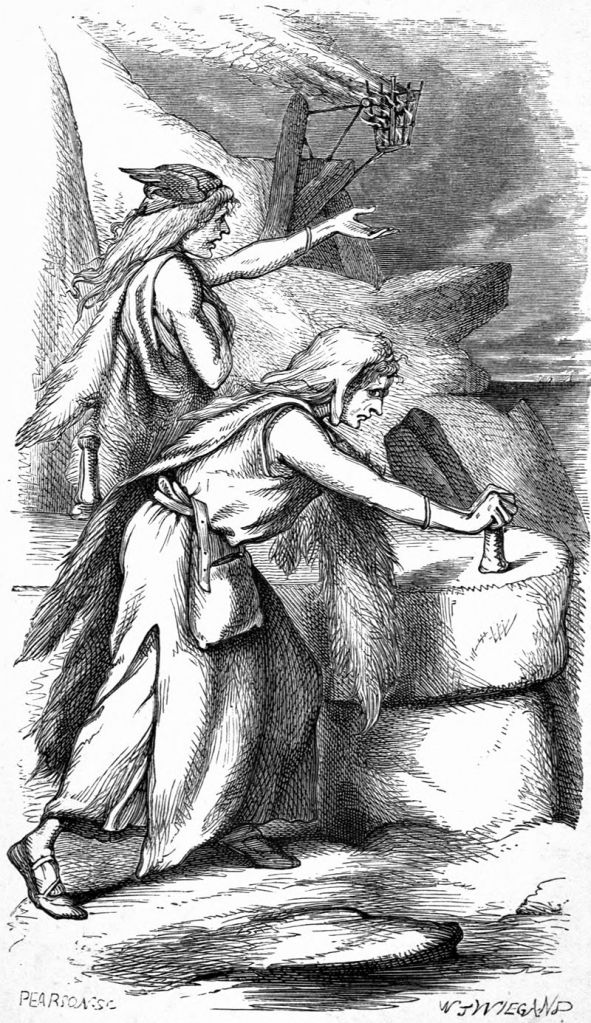

More than four others – Frisian Folkstale

At that time there lived in the Grinzer Pein (Friesland) a young man who was called out that he was not afraid of anything. When a ferry had to be dug, he got a job there. He joined the team with twenty westerners. Those twenty westerners were as lazy as duckweed. They wanted him to do the work, so he got into trouble with them. Then they said, “If you don’t work, we’ll cut you in pieces.” But the young man laughed and said, “You should try that first.” And then those twenty westerners came up to him with open knives , but he knocked them down one by one, for he was not afraid. And that same evening, near the new ferry, one of the Westerners was found cut into strips. But that joung man had not done that, his own comrades wanted to get rid of that westerner. And because the young servant had fought with him, they thought, he will be blamed.

That turned out to be the case, because the nineteen westerners testified that he must have been the murderer of their comrade. He went to court, and because he would not confess, he was put on the rack, but he maintained his innocence, for he was not afraid of anything, not even the pain. Desesperate, they called a wizard, a real wizard. He had to scare him so he confessed. The wizard had him tied on a chair; then he was powerless. But they had tortured him so much that he could hardly speak.

And then he was given a cup of warm milk to drink. The magician looked straight at him and said, ‘Look at the ground in front of you!’ And then the young man noticed that his ten toes had turned into ten snakes. They grew out of his toes, they grew bigger and bigger and came closer and closer to his head. But he made those snakes drink one by one from the hot milk from the cup he had in his hands. The snakes writhed together again and fell asleep at his feet.

The wizard asked, “Aren’t you scared yet?” But he replied, “You haven’t got any of those beasts yet, because my cup isn’t empty yet.” Then the wizard turned the boy’s hair into flames and said that he would be consumed by these flames. But the young man asked: ‘Do you have tobacco in your pocket? I don’t have any tobacco with me, but my pipe does. Stop it in front of me for a moment, so I can at least light it on the flames and don’t have to use a match’.

And the third was that the sorcerer sat before him and said: If you will not confess, you will be sent to hell. ‘But the young servant laughed, for he was not afraid. The wizard looked straight at him and then the young man noticed that his body was turning into a skeleton. The magician said:

“Aren’t you scared yet? Remember – this is how you go to hell and stay there!” “Oh,” he said, “why should I be afraid? Such an old charnel house as I am now – there is no one in hell who knows me.” And he did not bow the neck.

However, he was sentenced to death. The executioner appeared and he was to be cut into four. He was already on the block to be chopped in four, then they asked him if he wasn’t scared yet. “No,” he said, “why should I be afraid? Our father always said I was worth more than four others. And if you cut me in four here, you’ll be dealing with not one, but four men in a minute.’ And he was not quartered, but they took him back to the cell.

That same night the devil came to him and left nothing to frighten him. He told him the most horrible stories and transformed himself into the most horrible forms. The devil became an old woman, with teeth as large and as sharp as razors, and threatened to bite his throat. The devil became a dragon with seven heads that spewed fire at him. He became a very large snake, with a mouth so wide that it could eat it in one sitting. But the young servant was not afraid. Only when the devil finally asked him if he felt any fear at all did he say, “No, I don’t, but you do!

And he began to tease him so furiously, he made such hideous noises, and he drew such crooked faces, that even the devil became frightened and threw himself to the ground and blew the retreat.The judges came to the conclusion that a person that even the devil fears can never be a murderer. And he was acquitted…The judges came to the conclusion that a person that even the devil fears can never be a murderer. And he was acquitted…

=================================================================

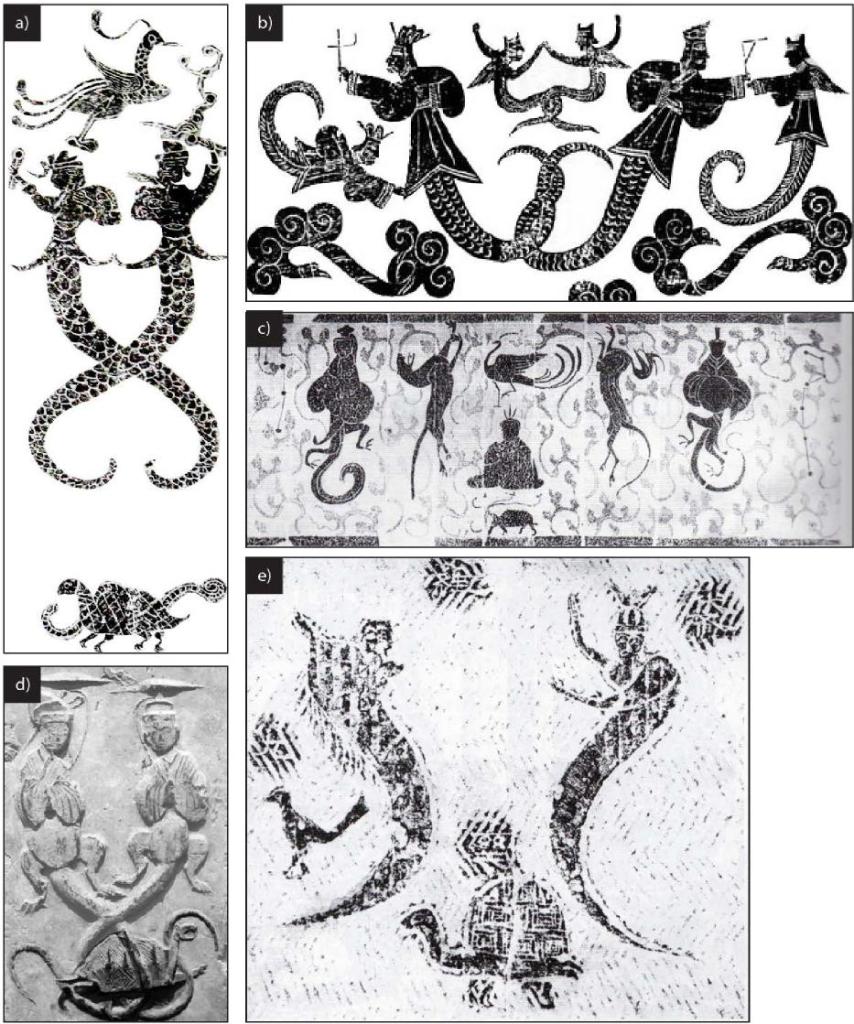

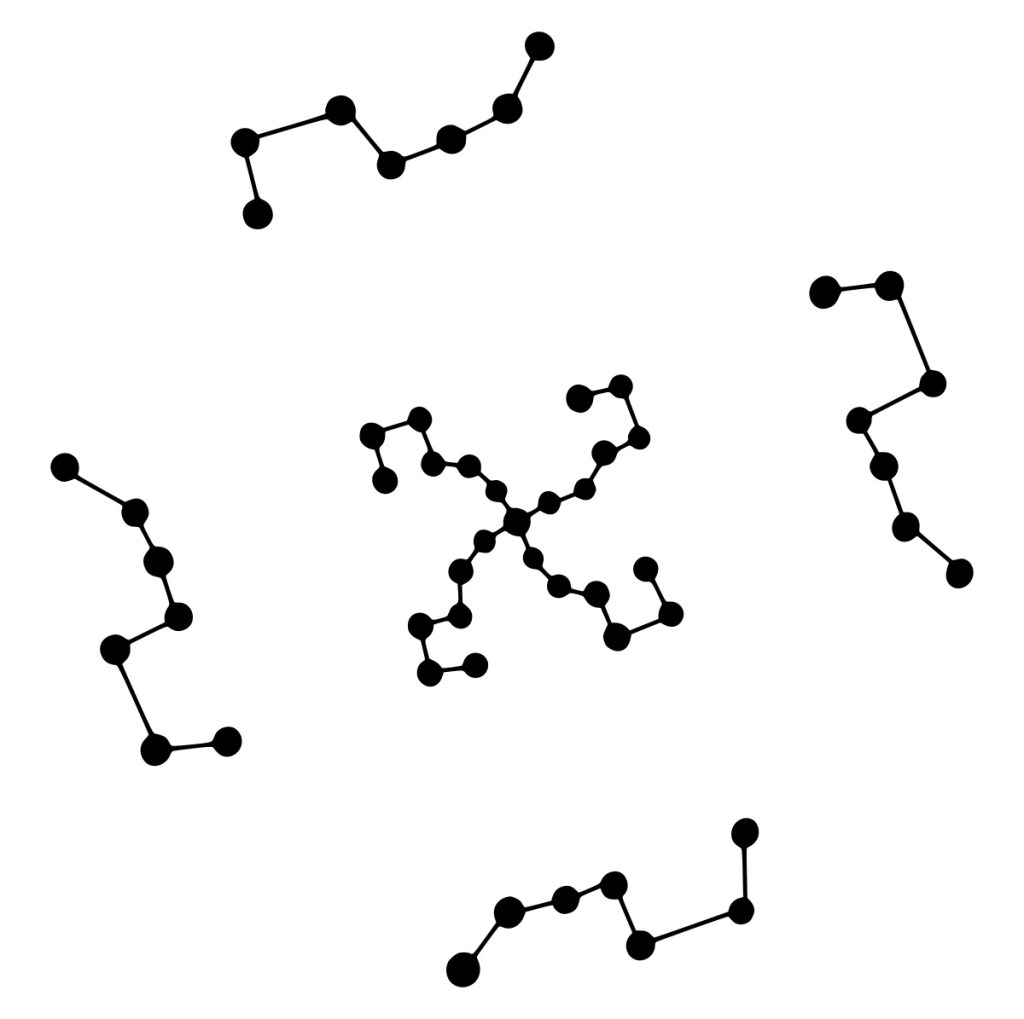

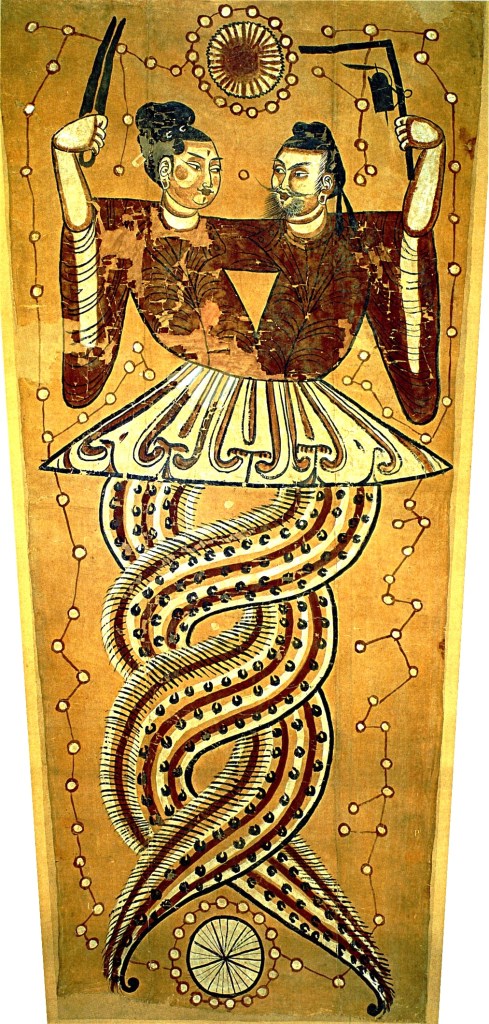

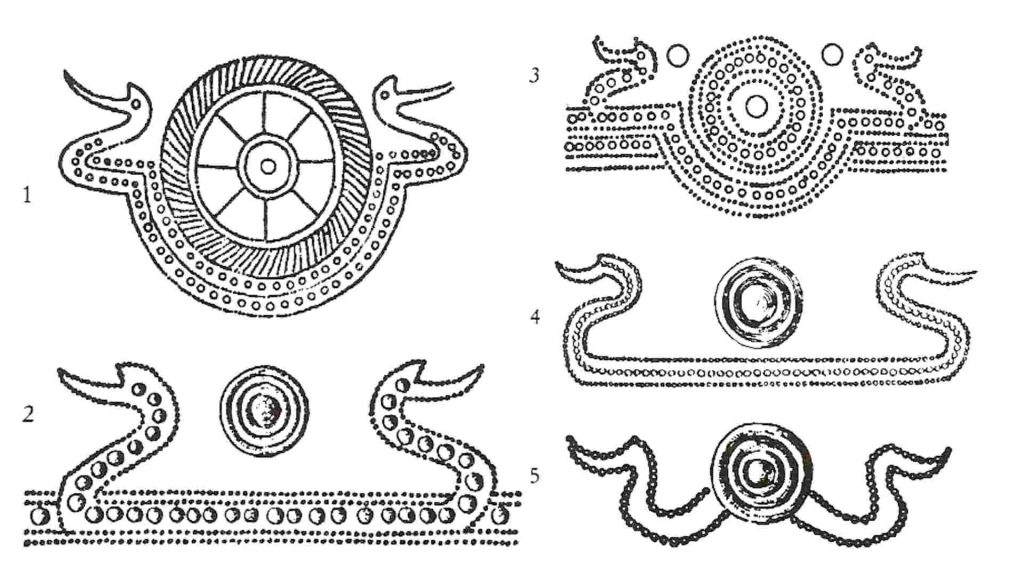

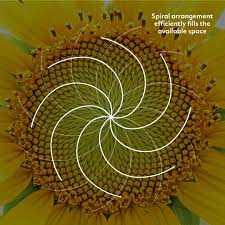

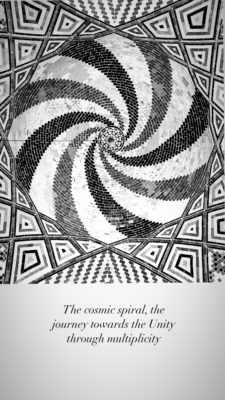

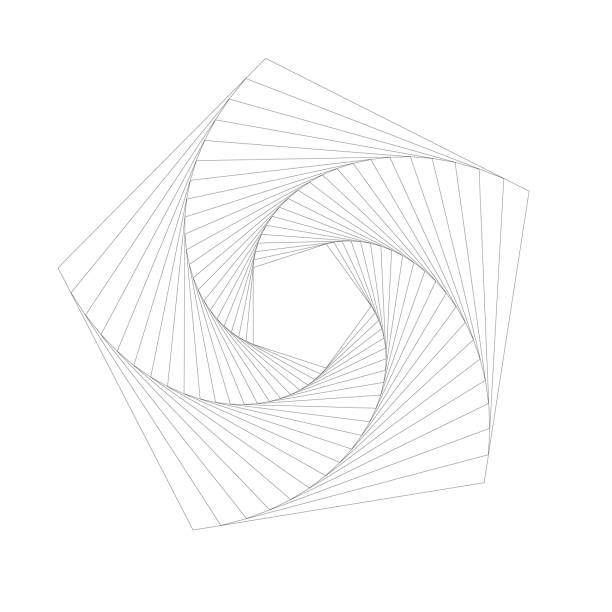

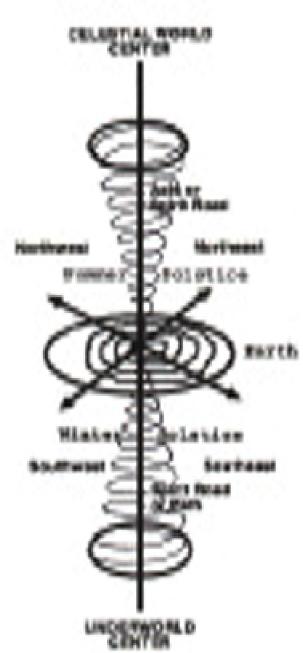

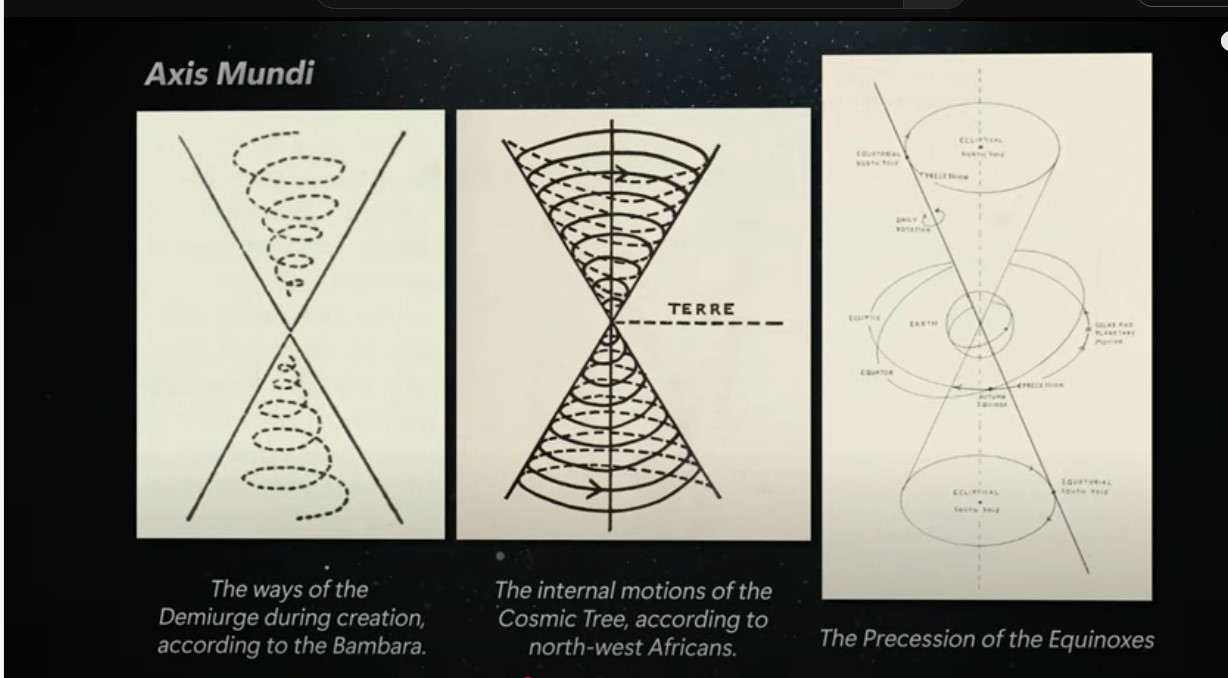

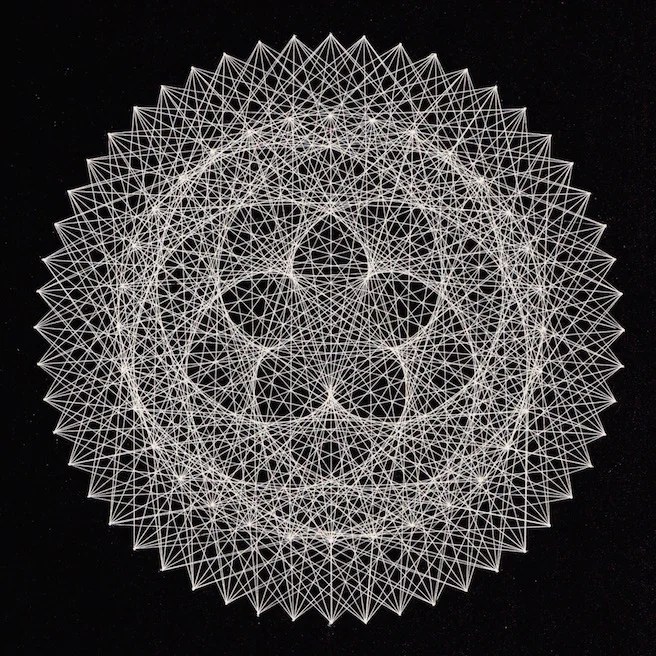

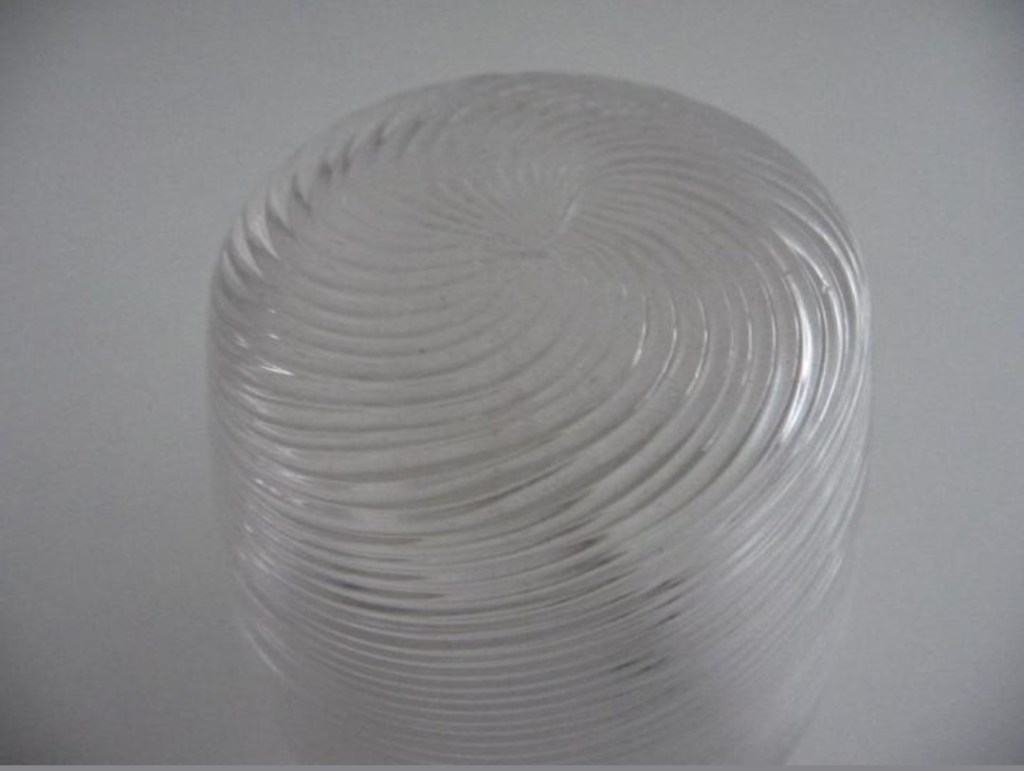

– Spiral

Spirals have been found in the form of pictographs or petroglyphs in most countries and cultures throughout the world. A simple design, it’s possibly the most common rock art motif in Colombia,appearing more times in the form of a petroglyph than a pictograph.

The white man Goes into his church house and talks about Jesus; The Indian Goes into his teepee and talks to Jesus. J.S. Slotkin

The shaman´s role in society

The role of the shaman in hunter-gatherer and horticultural societies has been written in detail by many authors (e.g.Vitebsky 1995). Generally speaking, the shaman is the tribal religious leader-healer who acquires supernatural powers, including power songs, from animals, birds, or reptiles during an initiation when he goes on a vision quest by entering a trance.

The shaman’s role encompasses tribal issues that are serious and need to be resolved. A community may be starving from lack of animals, crop failure due to flooding, freezing conditions, an extended drought or a tribal member may be very sick. The shaman is consulted to find the cause of illness and cure it. He may determine that the community has done something to cause an unbalanced cosmos, the soul has been stolen from a person or an evil object has entered the body of a person causing them to be sick.

Everyday illnesses and problems are resolved using chants, magical prayers, and incense. Using secret herbal potions, dances, power songs and rituals, the shaman summons his spirit helpers during a trance where he dies, is reborn, then battles and defeats hostile spirits causing the problem. He may suck a foreign object directly from the body of the ill patient to cleanse it of impurities or blow tobacco smoke on the patient.

During his spirit journey the shaman may fly up to the sky world or down to the underworld to plead with the spirit causing the problem, ask advice from deceased ancestors, physically battle evil spirits or win debates to gain concessions. The flight is usually upward to the heavens. When the shaman triumphs, h air or isolates him in a container or place where he can’t cause any more trouble.

After returning from this alternate reality, many researchers believe that shamans, or people under their direction, painted or engraved their visions, or symbols relating to them, on rocks One author wrote “It is probably extremely significant that the designs in many of the aspects of modern Indian artistry in the northwest Amazon are similar to or the same as those found in many of the rock engravings… Studies have indicated that these designs…are suggested by visions experienced during the

intoxication produced by caapi (Banisteriopsis Caapi),… There is no reason to doubt that the ancient artisans who made these rock-engravings had used the same drugs and had the same experiences as the natives of today” (Schultes 1988:80) (Figure 3b). These shamans enter the spirit world through a tunnel or spiral vortex portal and many believe that they actually pass through the stone surface at rock art site.

Trance stages

Modern studies of the brain have found that its main function is to make images. Under normal circumstances, external stimuli gathered by our sensory organs (eyes, ears, nose, skin, etc.) are received by the brain and processed.

The food we eat is the energy source used by the brain to perform its function. If external stimuli are blocked (e.g. isolation), or the food source is blocked or changed, in the case of toxins, or absent in the case of starvation, the brain reacts only to internal stimulation, and “abnormal” images are created.

These images, and those caused by physical pressure on the retina, are generally called entoptic phenomena and are composed of “phosphenes” (visual effects produced by mechanical pressure on the eye or electrical stimulation of the brain) and “form constants” (specific geometric shapes originating from other parts of the optic system away form the eye).

The brain may cut off reception of some external stimuli when its “normal” food source is not available and rely more heavily on internal stimulation. In the case of dreaming, for instance, the brain continues to do its job of making images using available stimuli to create a different “reality.”

The word Reality is difficult to define since each of us perceives the same material world in a similar, but slightly different way. One person may look at a tree and focus on the leaves, while another would concentrate on the bark. An artist may look at the general form of the tree or carefully note the root system or branches.

Altered Reality or Trance is a term used to describe a state where the brain has created images when its normal process has been interrupted by toxins, fatigue, starvation or a super-saturation of stimuli such as drumming, chanting, or dancing.

Spiral Symbolism

Clottes and Lewis-Williams (Clottes and Lewis-Williams 18) feel strongly that the three stages of a shamanic trance are universal and are an integral part of the human nervous system. One investigator has shown that the group of psychoactive drugs known as hallucinogens commonly used by shamans owe their activity to a very few types of chemical substances that act in a specific way upon a definite part of the central nervous system. Hallucinogens produce effects such as deep changes in the sphere of experience, in perception of reality, even of space and time and in consciousness of self.

Depersonalization may occur.

The trance state is short-lived, and lasts only until the causative substance is changed through digestion or excreted from the body. The effects of different hallucinogens vary according to the way they are prepared, the setting in which they are taken, the amount ingested, the number and kinds of additives, and the purposes for which they are used, as well as the ceremonial control exercised by the shaman. But all hallucinogens have similar trance STAGES as opposed to mood modifying psychoactive drugs such as analgesics and euphorics, sedatives and tranquilizers, and hypnotics (Schultes 13,14).

Therefore, apparently all trances induced by hallucinogenic plants have a transitional stage where shamans pass through a similar spiral or vortex tunnel. Waiká Indian shamans have stated that the most important part of their trance state is the transportation of their soul to other worlds (Schultes170). This implies that the spiral tunnel of the transition between stages 2 and 3 plays an important part of shamanic alternate reality visions and may have been recorded in rock art symbolizing the transitional stage, just as geometric shapes in rock art could be images from Stage 1, and realistic or floating animals in rock art could be created from Stage 3 images.

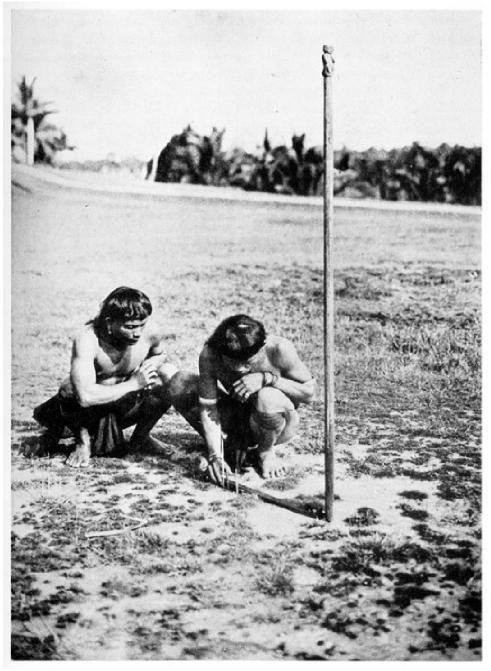

Anthropologists have proved that some Indians (e.g. Colombian Barasana shamans), reproduce geometric patterns in the sand that represent visions seen during their trances and paint their visions on the walls of their huts (Waimaja shamans). Interpretation of these design motifs is believed to be culture bound but, on the other hand, what is actually seen and recorded is controlled by specific biochemical effects of the active principles in the plant (Schultes 124).

Physiologically speaking, spirals seen during trances are caused by capillary circulation. The Tunnel Effect arises partly from the foveal cones and environing rods being smaller and more closely arranged than those of the periphery and in consequence the geometric figures perceived are likely to be smaller in the center than at the periphery (Marshall 300)

SEE;The colombian rock art spiral. A shamanic tunnel

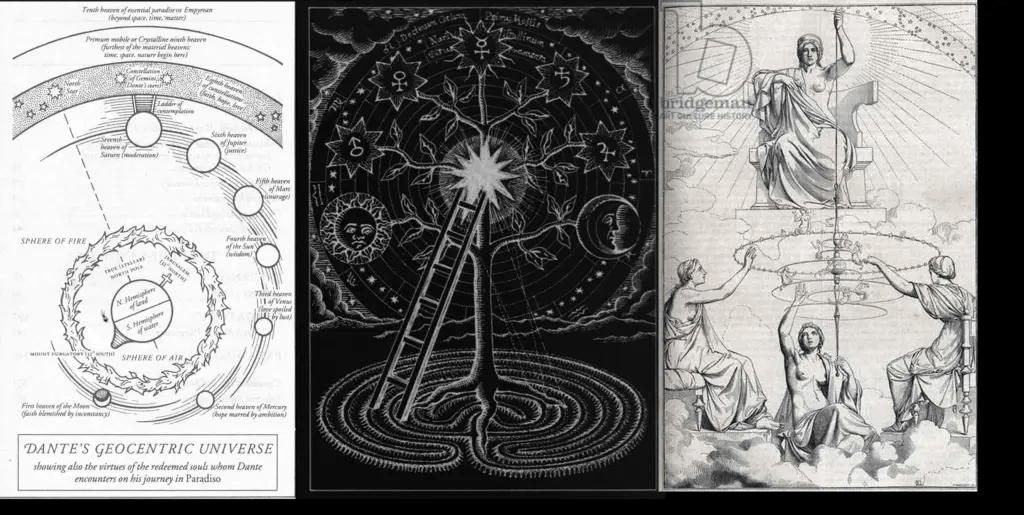

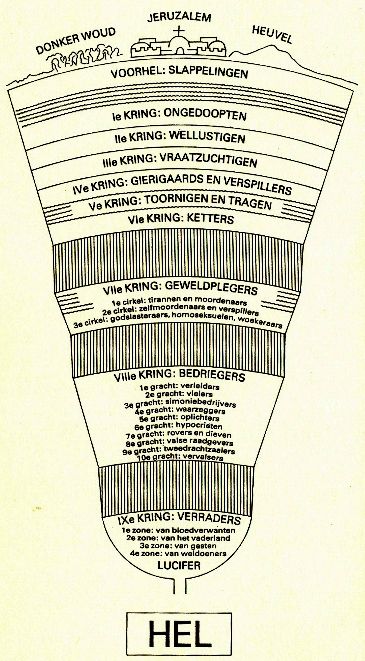

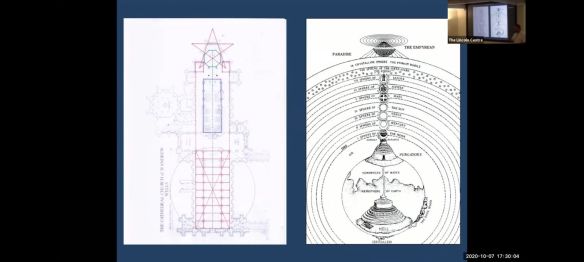

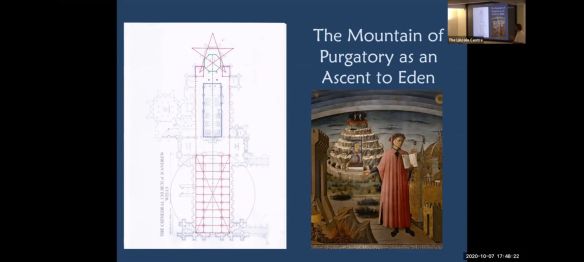

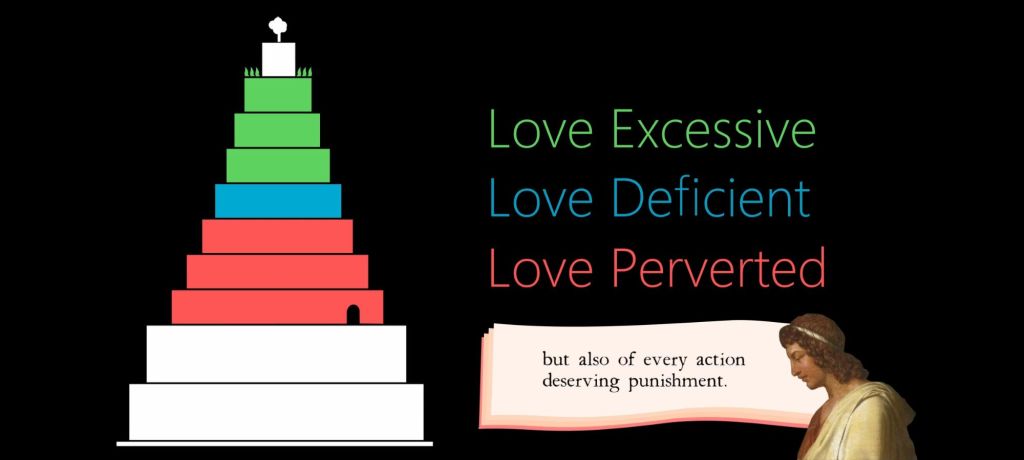

- Tom Bree – Dante’s Journey In Gothic Cathedral Design

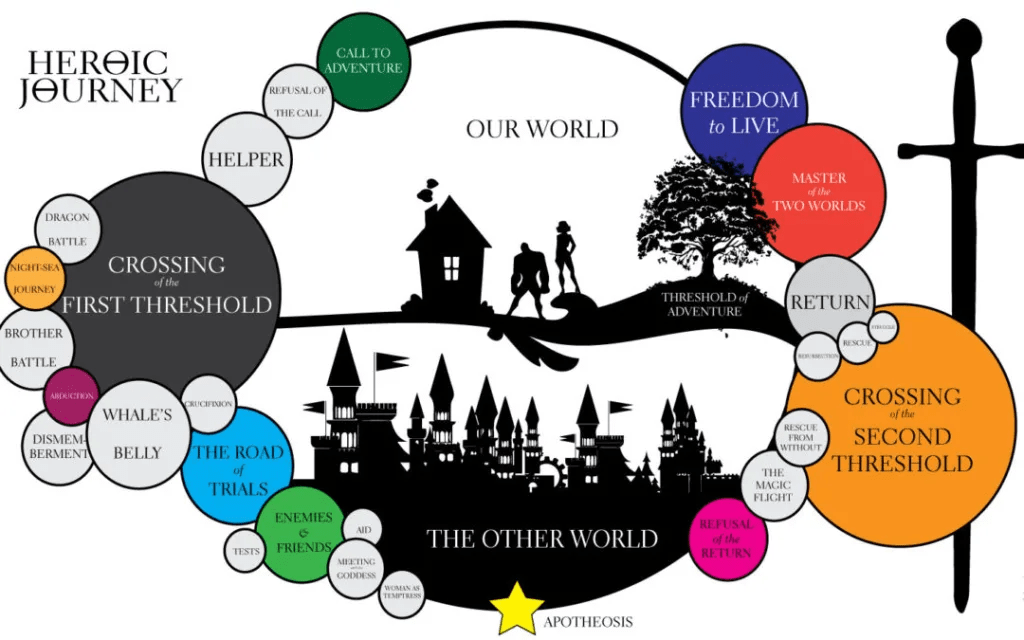

The eastward journey through a cathedral forms a symbolic ascent climbing towards the place of the rising sun. However for the soul to return to its heavenly origin a certain lightness and buoyancy is required as attested to by the image of St Michael in which he weighs human souls on judgement day.

Within Dante’s poem, Commedia, such a preparation for ascent requires him to first descend to the Inferno so as to face the very lowest reaches of the soul’s potential. Only then can he slowly begin his rise back upwards, first to the surface of the earth followed then by an ascent to Eden which lies at the summit of the Mountain of Purgatory. Finally he ascends through the heavens to the Empyrean where he becomes reunited with the soul’s divine origin.

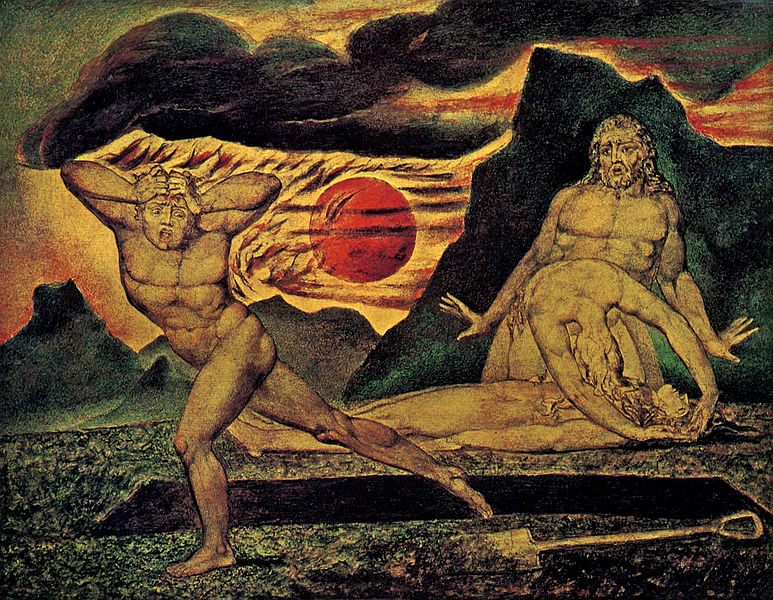

Dante’s journey is made in emulation of Christ because he descends to the inferno from Jerusalem on the afternoon of Good Friday and then re-ascends to the surface of the earth again on the morning of Easter Sunday. In this way he personally re-encounters the Harrowing of Hell which is Christ’s necessary descent into the underworld prior to His Resurrection on Easter Sunday and eventual ascent into heaven 40 days thereafter.

This illustrated talk will demonstrate how the three stages that characterise Dante’s journey are also present in the design of the ground plan of the first English Gothic cathedral. In this sense the beginning of the journey through Wells Cathedral is actually one of descent and only then can there subsequently be an eastward ascent towards the rising of the Bright Morning Star.

IN Purgatory, time and process are all-important. The souls are hastening to complete their purgation, and their cry is always, “Lose no time! Pray that my time be shortened! Hinder me not!”—so eager are they to speed their progress from circle to circle up the height. Into this realm, Virgil could not go without Dante; he is still his companion but no longer in the strict sense his guide. […] The journey takes us up the Mountain, past the souls of the excommunicate and the late-repentant who are anxiously waiting to begin their purification, up the three steps through St. Peter’s Gate, up by the seven cornices where the stain of the seven Capital Sins is cleansed away, till we come to the bird-haunted forest at the summit. And here Dante meets Beatrice.

LITERALLY, the [“enchanted”] Wood [i.e. the Garden] is the Earthly Paradise—the Garden of Innocence from which Adam and Eve were driven, through their own fault, at the Fall. It is the original starting-point of mankind. That is the crux of the matter; it is a starting-point. It is the point from which Man ought to have started his journey to God—from which every individual man would start now, but for the legacy of original sin, which has exiled him and obliges him to start as best he can from the wilderness, and sometimes from the Dark Wood which is sin’s deadly substitute for that other. It is also the point to which every man must return, in order to make his fresh start. It is reached by way of the Mountain of Ascent. Some —those who have kept in the right way—are able to take “the short way up the Hill—del bel monte it corto andar”; others who, like Dante, have gone so far out of the way that they cannot pass the Beasts, can only come to it by the long way that leads through Hell and up the Purgatorial path on the other side of the world, which is also the road taken by the blessed Dead. They come to the Earthly Paradise, but they do not stay there. Once there, once purged and restored to the lost innocence of their original nature, they start again, where Adam started, on the road that Adam should have taken. All the journey, all the toil, all the passing through the little and the greater death, is done that man may come back to his true beginning, to the original starting-place from which he may “leap to the stars”.

See The Cosmos in Stone: the Ascent of the Soul and Cosmology in Sufism

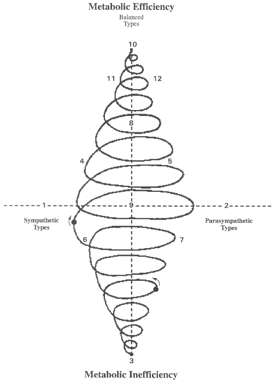

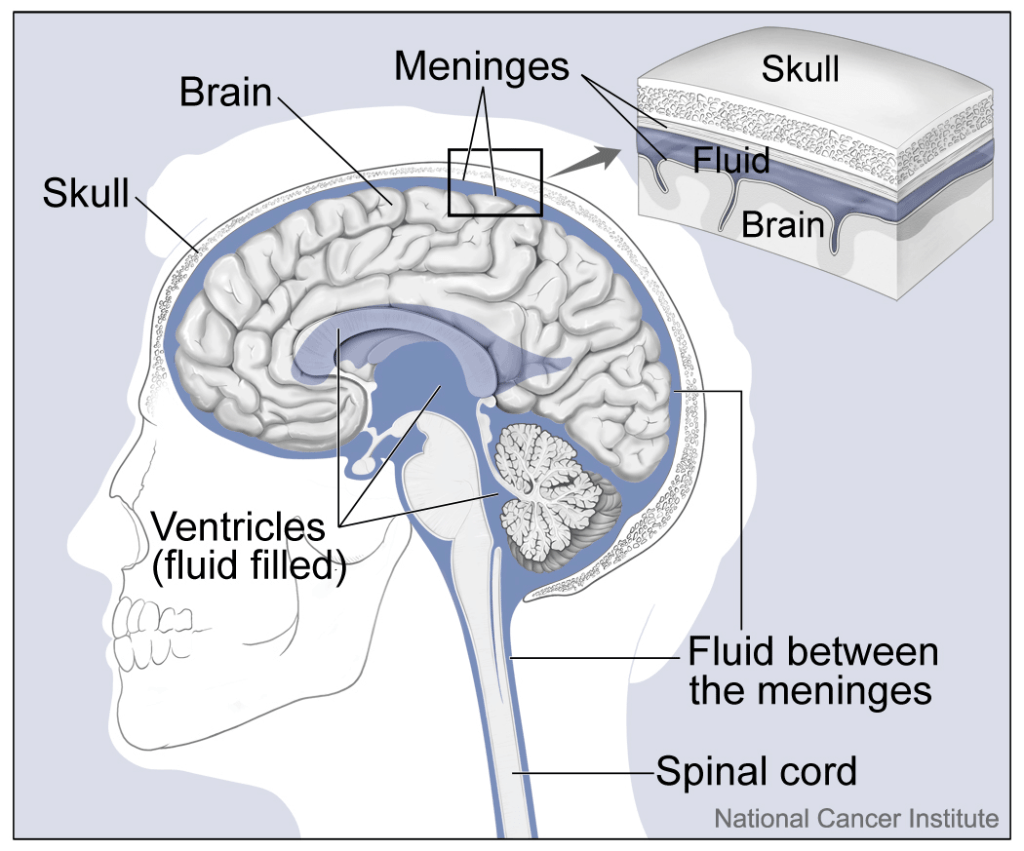

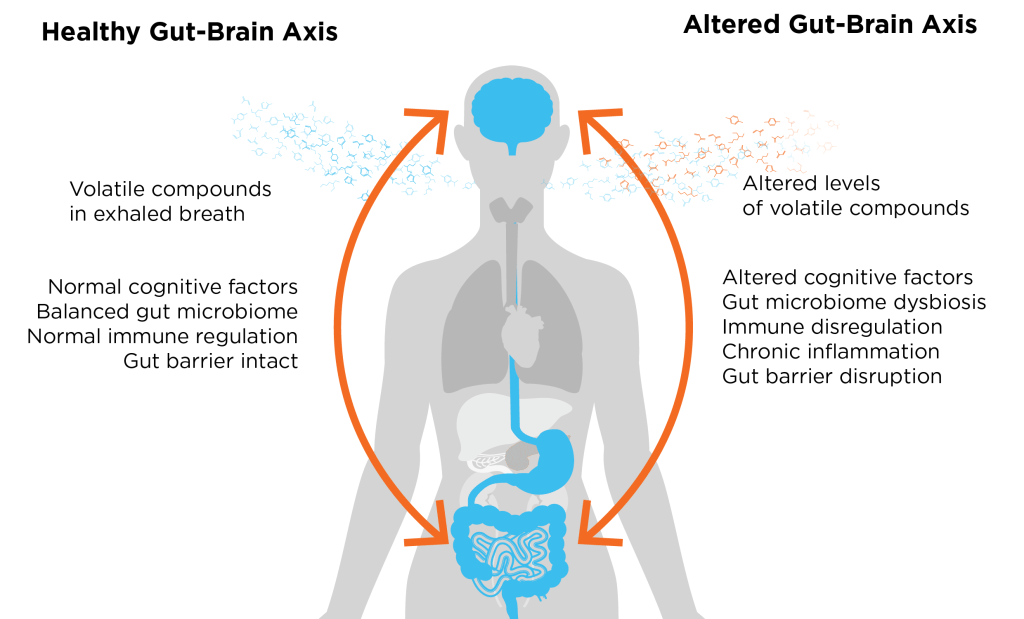

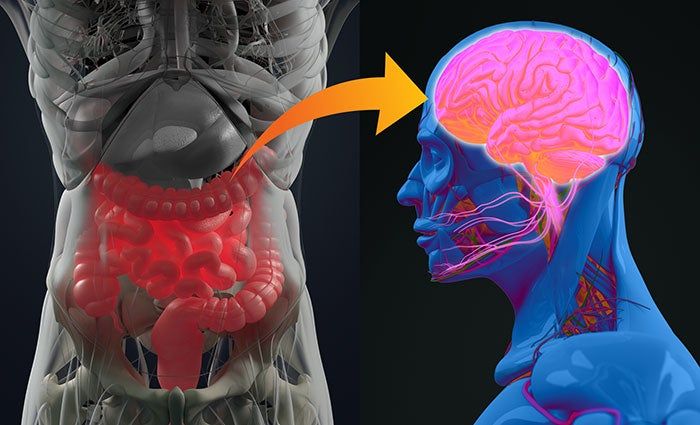

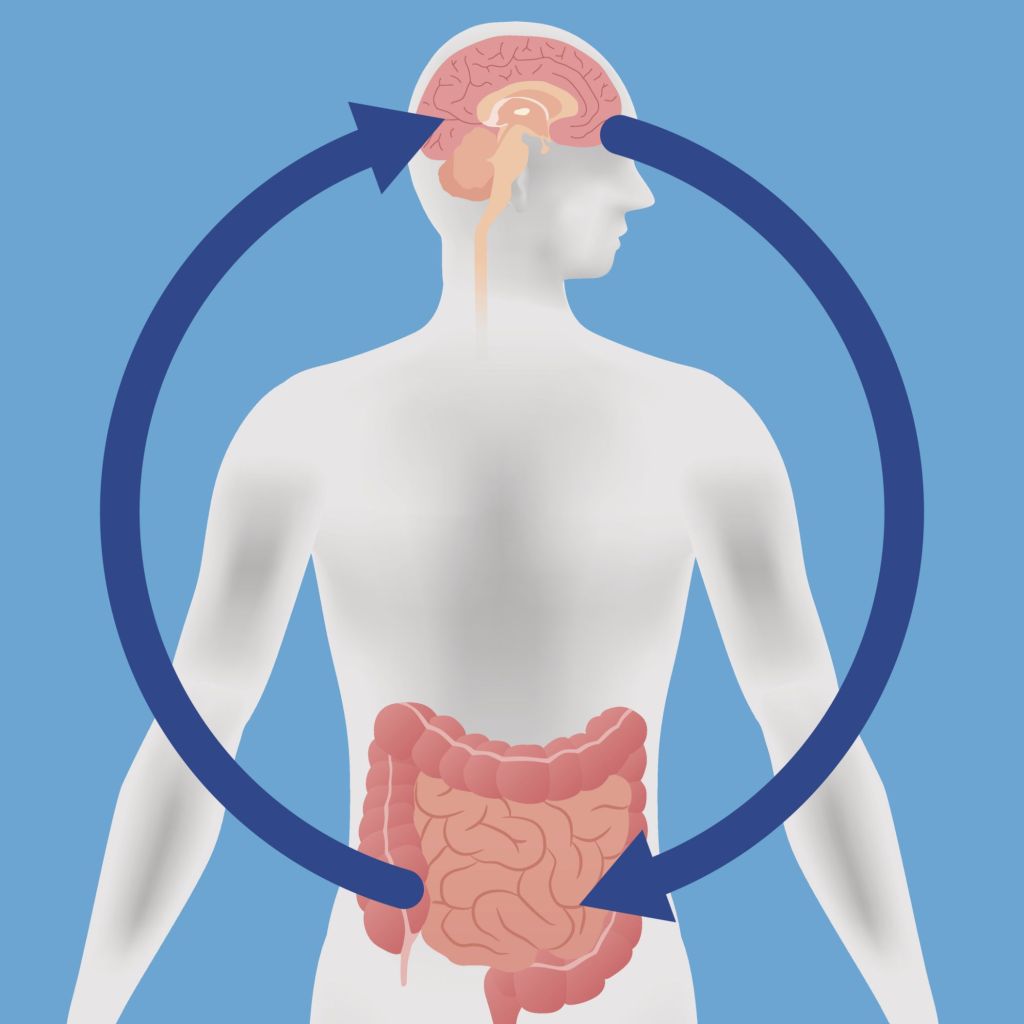

– Brain , gut…and the Heart

Although it can’t compose poetry or solve equations, this extensive network uses the same chemicals and cells as the brain to help us digest and to alert the brain when something is amiss. Gut and brain are in constant communication.

“There is immense crosstalk between these two large nerve centers,” says Braden Kuo, MD, MMSc ’04, co-executive director of the Center for Neurointestinal Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “This crosstalk affects how we feel and perceive gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and impacts our quality of life.”

Normally, when we see something tasty, the brain signals the gut to prepare for incoming food. When we feel anxious or stressed, we might experience these as abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, or “butterflies.” Messages travel from gut to brain, too. This helps explain why, when we eat something that makes us sick, we instinctively avoid the food and even the place we found it.These everyday activities can go awry when gut nerves are damaged or malfunction. The Center for Neurointestinal Health treats patients with life-altering conditions such as chronic constipation, extreme bloating, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Center physician-scientists also contribute to the exciting basic, clinical, and translational research happening across HMS to understand the gut-brain connection.

Messages travel from gut to brain, too. This helps explain why, when we eat something that makes us sick, we instinctively avoid the food and even the place we found it.

For example, Kuo and colleagues are measuring brain activity in patients with chronic nausea using functional MRI, which detects blood-flow changes. Their discovery that nausea and pain involve similar nerve centers has prompted new treatment plans for certain patients, potentially improving their quality of life.

Center researchers are also investigating how the trillions of bacteria in the gut (the gut microbiome) interact with the enteric nervous system (a component of the autonomic nervous system) and ultimately with the central nervous system, notes center co-leader Allan M. Goldstein, MD ’93, Marshall K. Bartlett Professor of Surgery at HMS and chief of pediatric surgery at MGH. “Increasing evidence is showing that bacteria in the gut, and the byproducts they produce, affect mood, cognition, and behavior.”

HMS Instructor in Medicine Kyle Staller, MD ’09, MPH ’15, is studying how abnormal body image and eating disorders in adolescents influence the likelihood of developing IBS and other GI problems in adulthood. These patients, he says, typically perceive normal digestion sensations, like the gut’s expansion with food and stool, as abnormal and may seek a doctor’s help for bloating.

Kuo has also co-led a pilot study that found the “relaxation response,” a state of deep rest induced by practices such as meditation and yoga, helped relieve symptoms in some patients with IBS and inflammatory bowel disease.

With the brain and gut so intertwined, it makes sense for clinicians treating gastrointestinal disorders to include cognitive approaches such as talk therapy, hypnosis, or relaxation response in their recommendations, and for clinicians treating cognitive symptoms to consider what’s happening in the patient’s gut.

- From the pont of view of traditional wisdom, the brain is seen as an adverary to fight against for spiritual grow to reach the Heart

“The secularity of the society in which we live must share considerable blame in the erosion of spiritual powers of all traditions, since our society has become a parody of social interaction lacking even an aspect of civility. Believing in nothing, we have preempted the role of the higher spiritual forces by acknowledging no greater good than what we can feel and touch.” Vine Deloria Jr

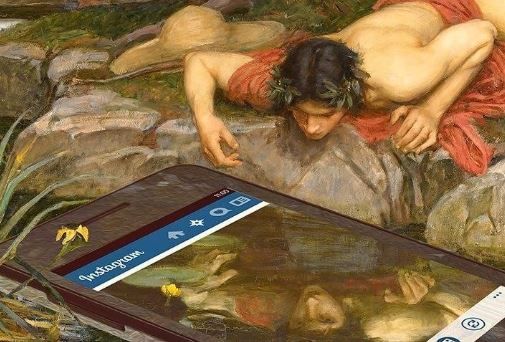

The perspective of modernity where Western Man as the egolatrous being is placed at the top of existence for all others to look towards for recognition.

The pyramidal construction of Man from an Islamic perspective shifts our understanding of the seriousness of placing the egolatrous Man above God in constructing reality, while simultaneously allowing us to imagine what would be necessary in creating a transmodern critique in constructing the Human.

We are not the first generation to know that we are destroying the world, many communities and civilisations collapsed before us. But we could be the last that can do anything about it, not with the vanity of earthly knowledge and so called democratic solidarity and wisdom here on earth , but with asking humbly the help of Divine Wisdom so realising in us the image of the man who painfully transcends his material ego: The birth of his soul. It is a test. It’s time to decide!

To start our Migration to the Spiritual Land of Peace , we look at an old text known as papyrus 3024 from the Berlin Museum, known as “Man arguing with his Soul” or the “Rebel in the Soul” we can perhaps study one of the earliest accounts of the confrontation with the ego.

– Rebel in the Soul: An ancient Egyptian dialogue between a Man and his Soul

andThe Rebel in The Soul: The Wisdom of Ordinariness

See alsoThe Dragon Slayer: on becoming an adult

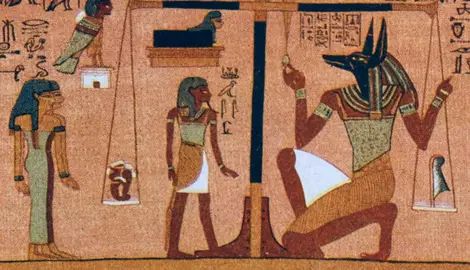

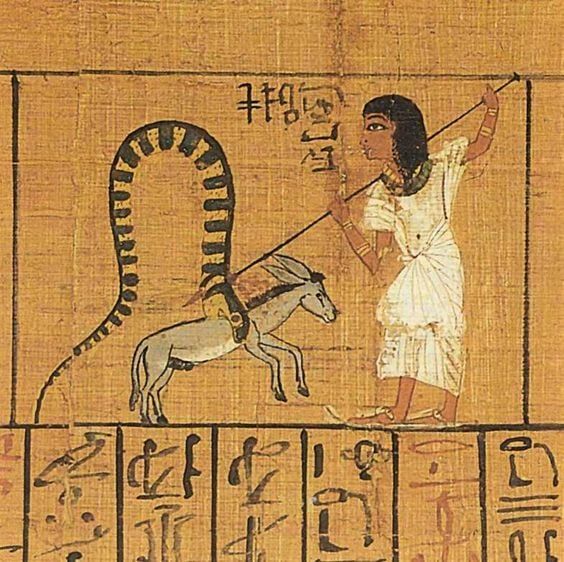

The Weighing of the Heart Ceremony & Its Role in the Egyptian Afterlife

The Weighing of the Heart ceremony was an essential step in passing from the world of the living to the realm of the dead in ancient Egypt.

One of the most famous scenes surviving from ancient Egyptian art is the Weighing of the Heart Ceremony, during which the heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of Ma’at. If the heart was lighter than the feather, they passed into ancient Egypt’s paradisical afterlife. If it was heavier than the feather, they were devoured by the monster Ammit and resigned to oblivion. This belief was so important to Egyptian culture from at least the New Kingdom onwards that it was immortalized in Egypt’s most common literary text, the Book of the Dead.

manas (Sanskrit: मनस्, “mind”) from the root man, “to think” or “mind” — is the recording faculty; receives impressions gathered by the sense from the outside world. It is bound to the senses and yields vijnana (information) rather than jnana (wisdom) or vidya (understanding). That faculty which coordinates sensory impressions before they are presented to the consciousness. Relates to the mind; that which distinguishes man from the animals. One of the inner instruments that receive information from the external world with the help of the senses and present it to the higher faculty of buddhi (intellect). manas is one of the four parts of the antahkarana (“inner conscience” or “the manifest mind”) and the other three parts are buddhi (the intellect), chitta (the memory) and ahankara (the ego).

Characteristics of Manas

The perceiving faculty that receives the messages of the senses.

The instinctive mind, ruler of motor and sensory organs.

The seat of desire.

Is termed the undisciplined mind.

Is fraught with contradictions: doubt, faith, lack of faith, shame, desire, fear, steadfastness, lack of steadfastness.

This particular faculty is characterized by doubt and volition.

The mental faculty, that which distinguishes the human from mere animal.

The individualizing principle; that which enables the individual to know that he or she exists, feels and knows.

manas itself is mortal, goes to pieces at death — insofar as its lower parts are concerned.

Divided into two parts

buddhi manas (higher mind)

kama manas (lower mind), refers to lower mind; kama meaning “desire.”

For René Guénon, it is an “instrument of sensation” corresponds to an “entry”, and “an instrument of action” to an “exit” which “executes”, between the two, manas examines. Manas, as an internal sense, includes reason, memory and imagination; the sentimental dimension being it intermediate between this direction and the bodily element [3]. René Guénon remarks that manas, the “mind” or “internal sense”, to which the “self-consciousness” (ahaṃkāra) is inherent, is in the Hindu tradition a characteristic of human individuality that differentiates it from other beings in the living world. He notes that the root of this Sanskrit word is found in the Latin mens, the English mind, mental etc. This root man or men is often used in words used to designate the human being himself. Manas is situated between the five “faculties of sensation” and the five “instruments of action” [4]. “The five instruments of sensation are: the ears or hearing (shrotra), the skin or touch (tvak), the eyes or sight (chakshus), the tongue or taste (rasa), the nose or the smell (ghrana) […] The five instruments of action are: the organs of excretion (payu), the generating organs (upastha), the hands (pani), the feet (pada), and finally the voice or the organ of speech (vach) […] The manas must be regarded as the eleventh ”

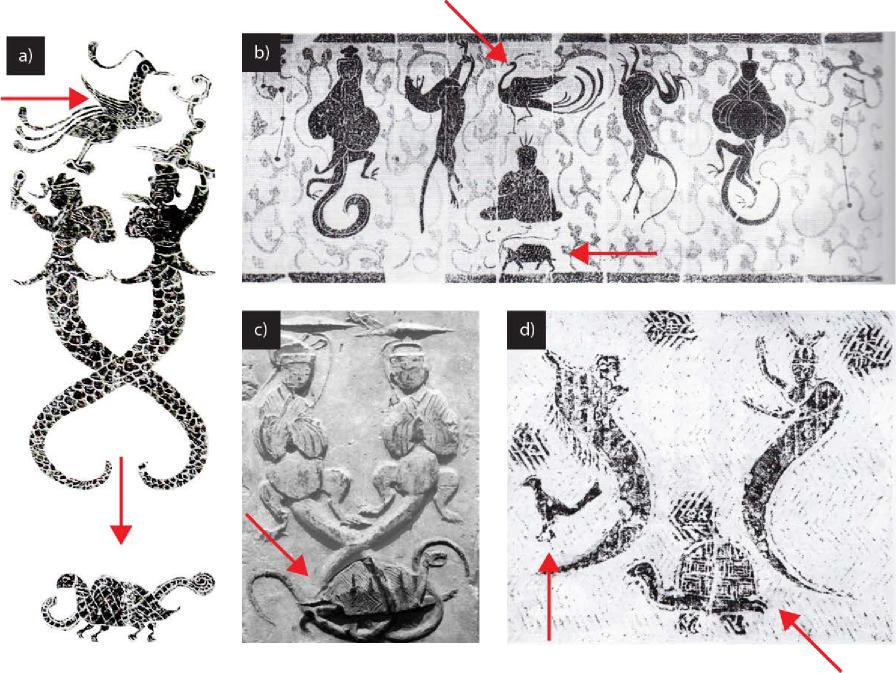

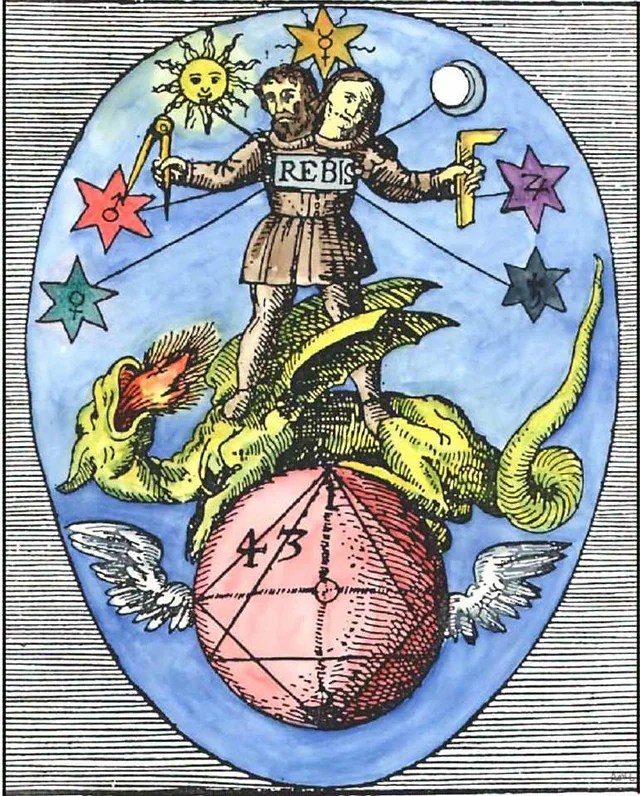

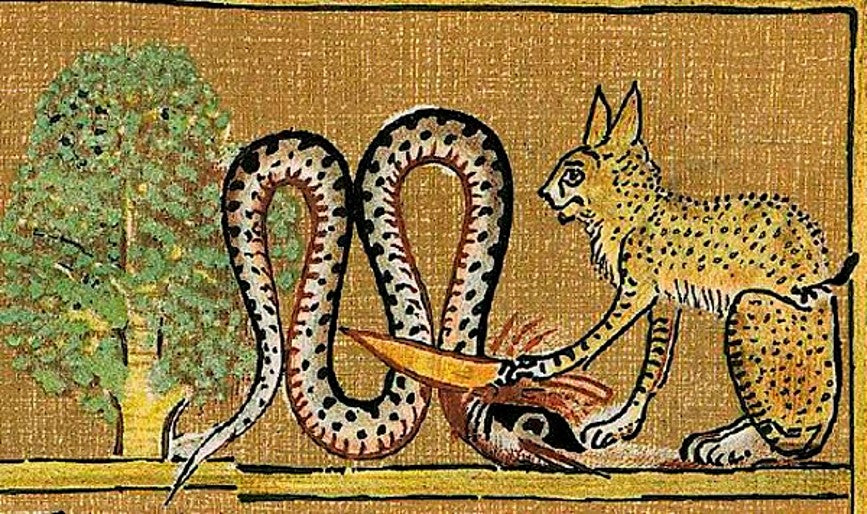

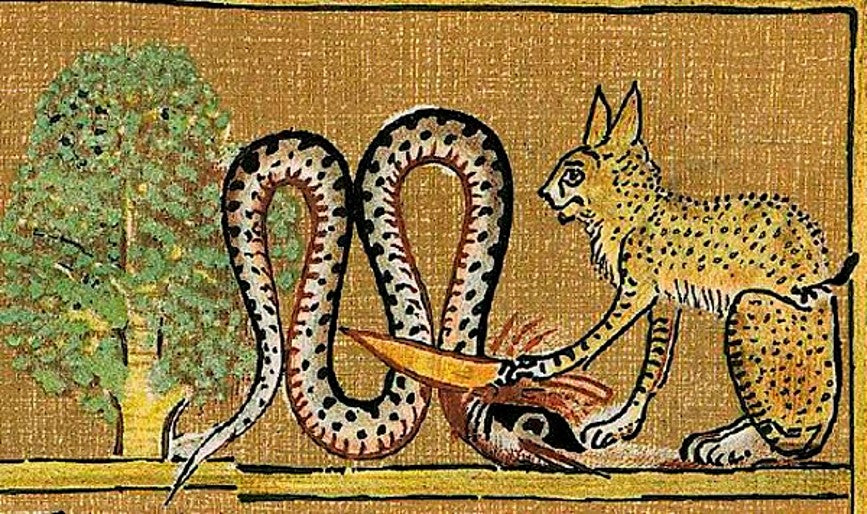

apophis god serpent

Apophis’s myth exemplifies ancient Egypt’s deep concern with the cosmic struggle between light and darkness, order and chaos, embodied in the nightly contests of sun and serpent.

What myths explain Apophis’s origin and role

Apophis’s origin and role in Egyptian mythology are explained by several creation myths and ritual traditions, each emphasizing his identity as the primordial enemy of order and the sun god Ra.

Unlike other deities, Apophis was not worshipped but was ritually repelled, emphasizing his role as an immortal and fearsome force of destruction whose existence continually challenges cosmic harmony. Egyptians enacted rituals to weaken him, symbolically defeating chaos and reaffirming the triumph of order with each sunrise.

Symbolic and Ritual Significance

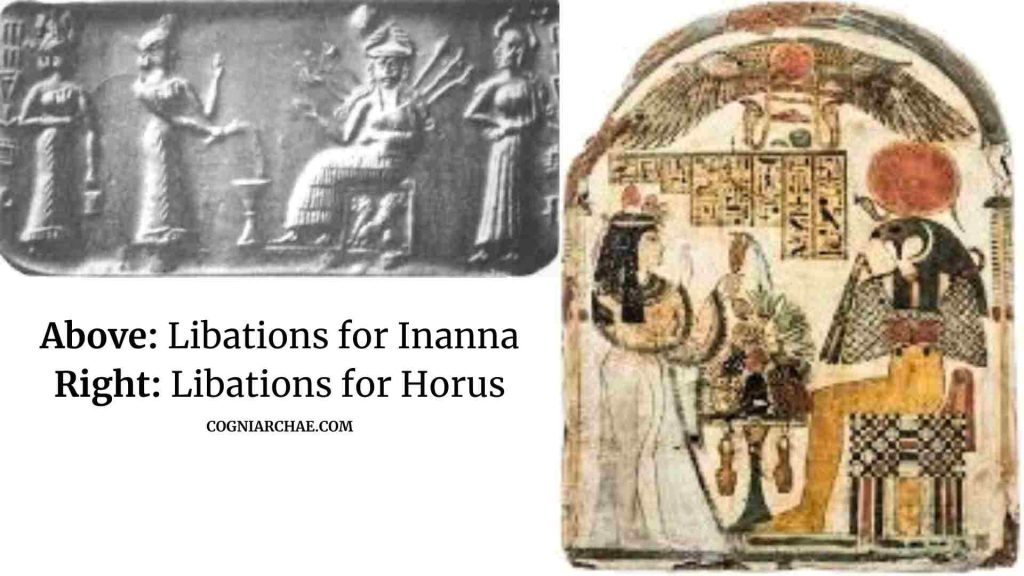

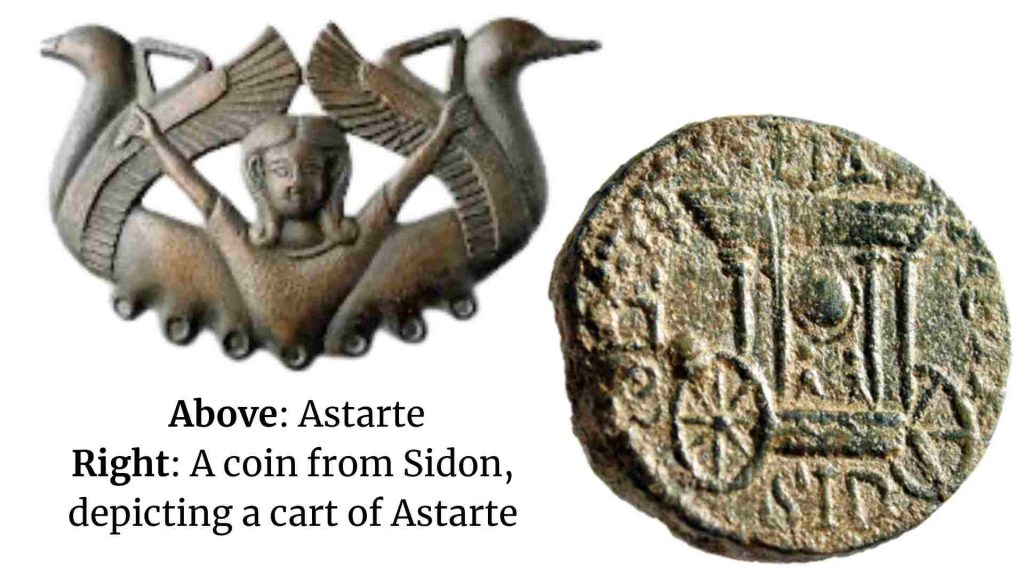

Comparison with Other Near Eastern Chaos Serpents

Other chaos serpents appear in ancient Near Eastern mythologies with similar symbolic functions but differing visual and narrative contexts:

- Tiamat (Babylonian): Portrayed as a primordial sea dragon or multi-headed serpent, Tiamat is both chaos and creation. Following her defeat by Marduk, Tiamat’s corpse becomes the fabric of the cosmos—her skin forms the sky, her tail creates the Milky Way, and her body parts shape rivers and mountains. Tiamat’s imagery is more ambiguous, evolving from watery chaos to explicit dragon motifs especially in later texts and art.

- Lotan/Leviathan (Canaanite/Hebrew): Lotan and Leviathan are sea monsters or serpents with seven heads. They are shown battling storm gods (Hadad/Baal in Ugaritic myth; Yahweh in Hebrew texts), serving as metaphors for the containment of cosmic disorder. Leviathan’s depiction often carries connotations of monstrous power and is referenced allegorically as Babylon or other enemies. Lotan is sometimes associated with rivers and rain—his defeat symbolizes the restoration of balance.

- Vritra (Vedic): Although not as prominent visually as Apophis, Vritra is a serpent or dragon holding back the waters and sunlight, slain by Indra in a cosmic duel akin to Apophis’s nightly battles with Ra.

Table: Apophis vs. Other Chaos Serpents

NameCultureForm/DepictionSymbolismOpponent(s)Apophis (Apep)EgyptianColossal serpent, flint head, coiled, under attackChaos, darkness, destructionRa, Set, godsTiamatBabylonianSea dragon, multi-headed serpent, ambiguous formsPrimordial chaos, sea, creationMardukLotan/LeviathanCanaanite/HebrewMonster serpent, many-headed, river associationsCosmic disorder, enemy powerHadad/Baal, YahwehVritraVedicSerpent, dragonWaters withheld, darknessIndra

Apophis’s iconography and mythic role are echoed in—but distinct from—other Near Eastern chaos serpents, sharing the theme of cosmic conflict where order must eternally battle the serpentine force of chaos.

Apophis as a mythic figure can be metaphorically compared to the brain’s function in terms of representing the challenge between order and chaos within a complex system.

Comparison: Apophis and the Brain

- Apophis as Chaos: Apophis embodies primordial chaos, darkness, and the threat of destruction to cosmic order, continuously challenging the stability and function of the universe (through the sun god Ra). This can be likened to intrusive, chaotic elements that challenge an orderly system.

- Conflict and Balance: Just as Apophis is the unstoppable force of chaos requiring constant vigilance and defense by ordered cosmic forces, the brain must constantly manage internal and external “chaotic” stimuli—such as stress, emotional turmoil, or neurological disruptions—by employing regulatory mechanisms (e.g., the prefrontal cortex mediating emotional responses).

- Cycle of Threat and Recovery: Apophis’s nightly assault and defeat symbolize the recurring cycles of disruption and restoration of order—analogous to how the brain manages repeated challenges like stress, illness, or trauma, restoring equilibrium.

Mythic Symbolism in Cognitive Terms

- Apophis can be viewed as a symbol of disruptive neural or psychological forces (e.g., fear, anxiety, or disorder) that threaten the “light” of consciousness and rationality.

- The gods defending Ra are akin to neural networks or regulatory brain centers that maintain mental and physiological order.

- The persistent nature of Apophis’s threat reflects how challenges to brain regulation are ongoing and require active coping and resilience.

This metaphor highlights the ancient conception that cosmic order requires constant defense against chaos, much like brain function necessitates continual regulation against disorder to sustain life and consciousness.

Comparison: Apophis and the Heart

- Apophis as Threat to Life: Apophis represents chaos, darkness, and destruction seeking to devour the sun and plunge the cosmos into disorder and death. Similarly, the heart is the vital organ that sustains life through circulation; any disruption to its rhythm or function threatens life itself.

- Heart as Center of Vital Order: Symbolically and physiologically, the heart governs the flow of life-force (blood, energy) and symbolizes emotional and spiritual centers in many traditions. It embodies balance, vitality, and the sustaining power of order in an organism.

- Chaos Versus Harmony: Apophis’s role as a constant menace can be likened to factors that threaten the heart’s harmony—stress, fear, anxiety, or physical illness that disrupt the heart’s steady beating. In mythic terms, Apophis represents those disruptive forces that must be kept at bay to maintain the living order and vitality sustained by the heart.

- Duality in Symbolism: Just as Apophis’s chaotic nature opposes the sun’s ordered life-giving light, the heart symbolizes the sustenance of life and emotional equilibrium—undermined by chaotic emotional states or physical dangers. Apophis’s repeated defeats mirror the resilience of the heart to overcome threats and maintain steady rhythm.

- Emotional and Spiritual Dimensions: In esoteric symbolism and many religious traditions, the heart is the seat of virtues, love, and divine spirit, while Apophis personifies the dark, destructive unconscious forces that challenge these qualities.

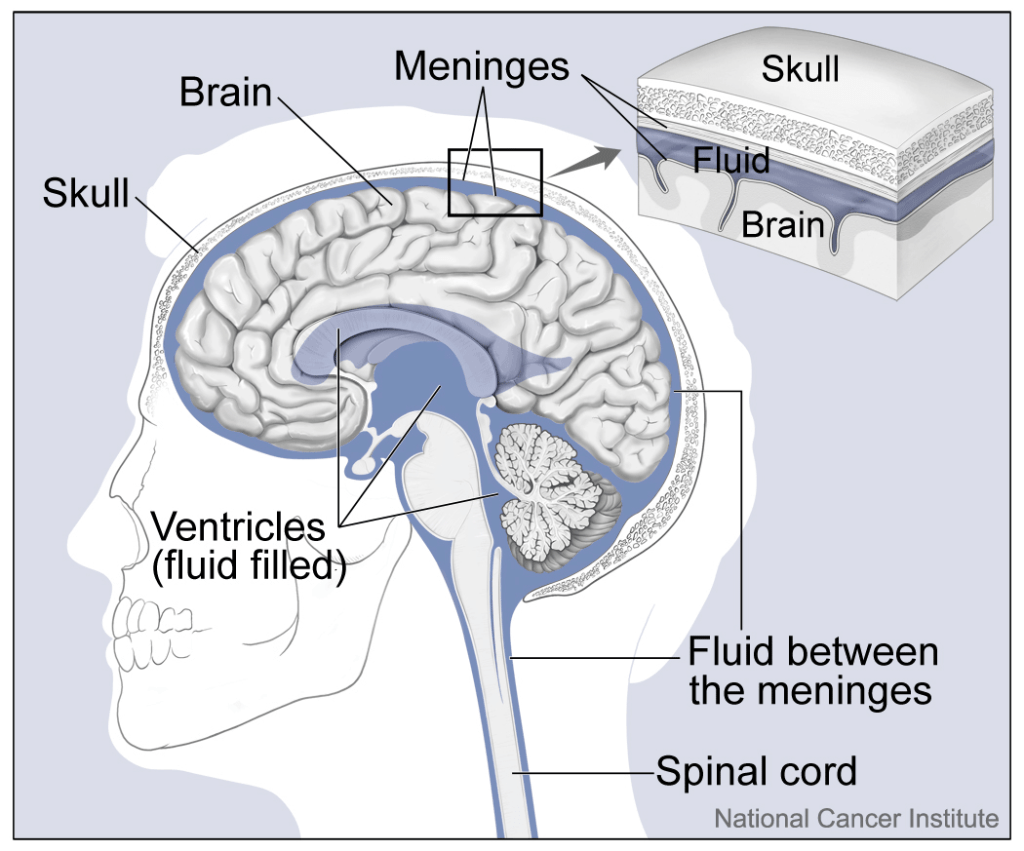

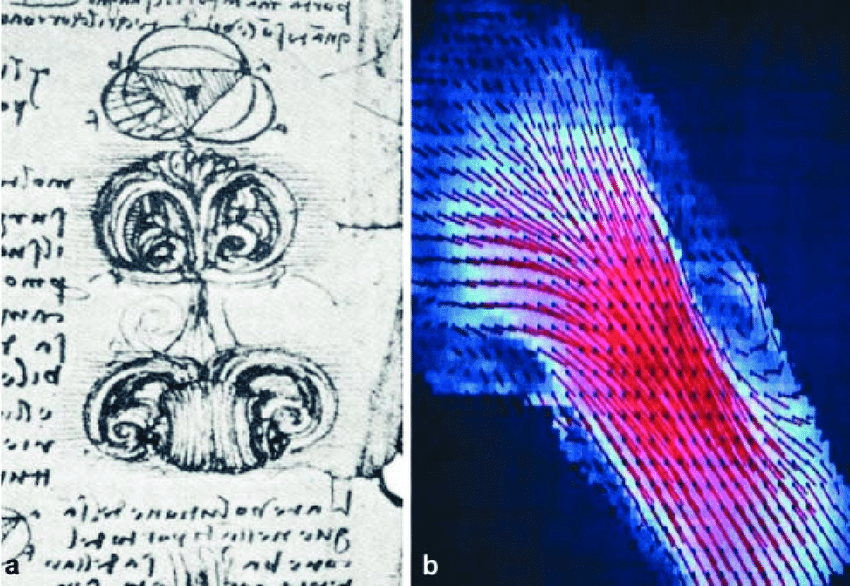

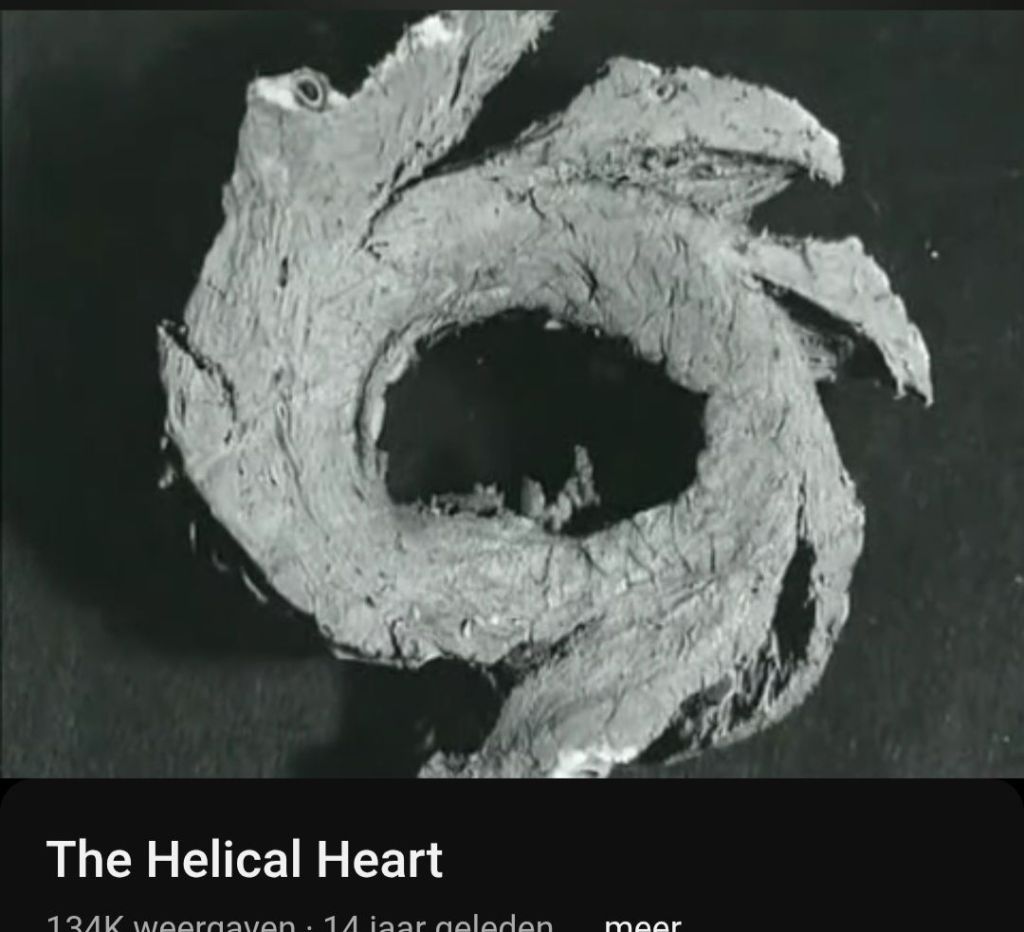

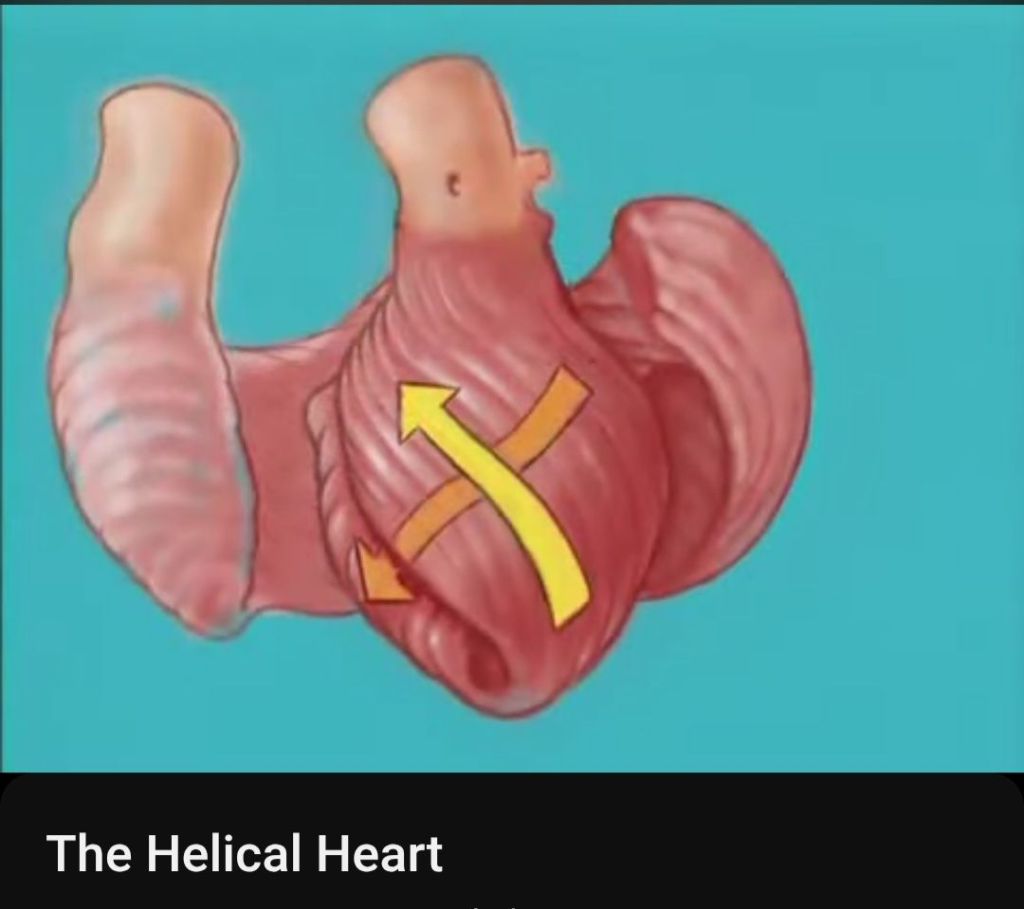

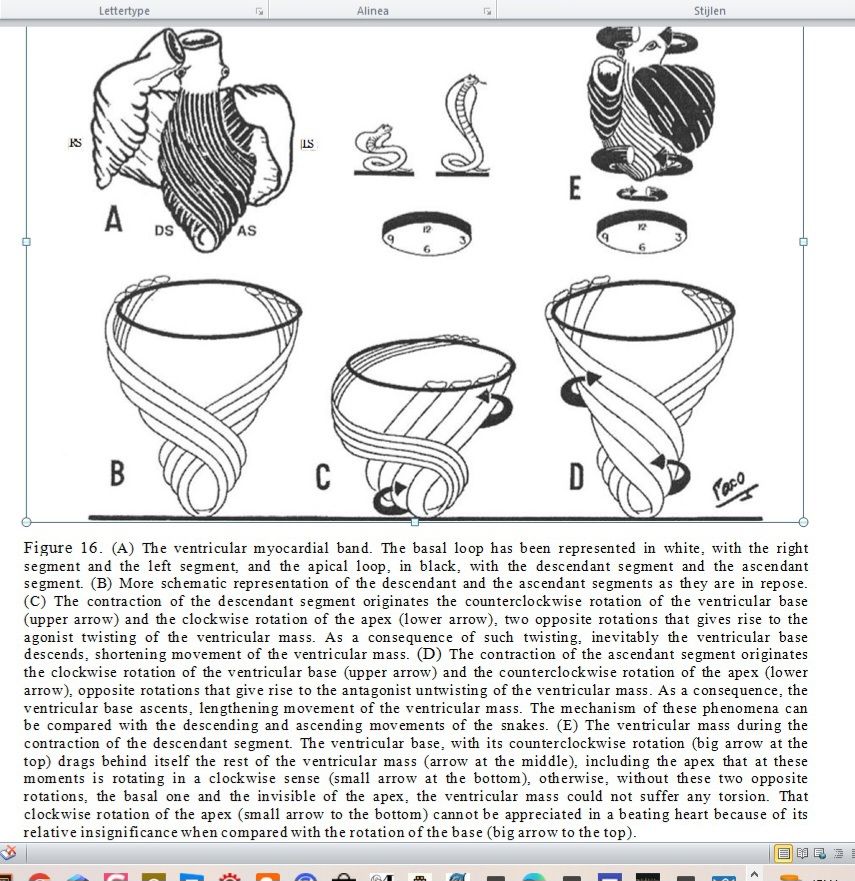

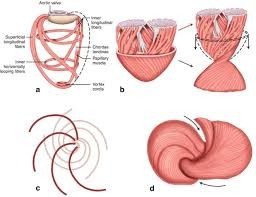

The heart has long been thought to be controlled solely by the autonomic nervous system, which transmits signals from the brain. The heart’s neural network, which is embedded in the superficial layers of the heart wall, has been considered a simple structure that relays the signals from the brain. However, recent research suggests that it has a more advanced function than that.

The heart has long been thought to be controlled solely by the autonomic nervous system, which transmits signals from the brain. The heart’s neural network, which is embedded in the superficial layers of the heart wall, has been considered a simple structure that relays the signals from the brain. However, recent research suggests that it has a more advanced function than that.heart connect to virtues neuron

There is emerging evidence that the heart is intimately connected to the formation and experience of virtues at a neural level, influencing moral emotions, decision-making, and cognition via heart-brain interactions and specialized neural networks.

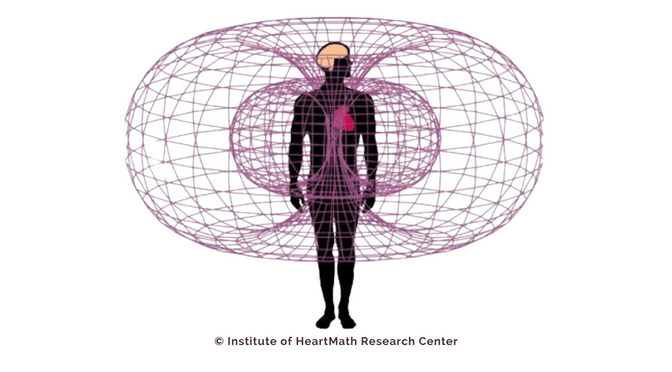

Heart-Brain Neural Networks

The heart possesses an intrinsic cardiac nervous system (ICNS) composed of about 40,000 sensory neurites, which communicate with the brain through afferent signals carried mainly by the vagus nerve. This feedback influences brain processes that shape emotional responses, mood regulation, and even higher cognitive functions such as decision-making and short-term/long-term memory, suggesting that the heart’s neural activity participates in virtue-related cognition.

Virtue and Moral Emotion Processing

Neuroscience has demonstrated that moral emotions and virtues activate specific brain areas, notably the default mode network (DMN), orbitofrontal cortex, and related regions associated with moral cognition and prosocial behaviors. Heart-generated signals can modulate these regions, for instance by heartbeat-evoked responses (HERs), strengthening the link between physiological states and neural processing of moral virtues.

The heart’s neural feedback may play a subtle role in decision-making, intuition, and emotional adaptation—qualities central to virtue ethics. Cardiac neural input can affect the robustness and connectivity of brain networks linked to compassion, moral indignation, and other virtuous responses, suggesting a bidirectional system where the heart shapes cognition and moral self.

Clinical and Philosophical Perspectives

This heart-brain connection opens new pathways for understanding not only cardiovascular disease treatment but also how emotional intelligence and moral development can be holistically cultivated. Virtue ethics grounded in both neuroscience and classic philosophy now considers heart-neuron networks as integral for moral flourishing and character.

In summary, the heart’s neural system, through communication with the brain, is increasingly recognized as foundational to the realization and neural embodiment of human virtues, offering a bridge between physiology, emotion, and ethics.

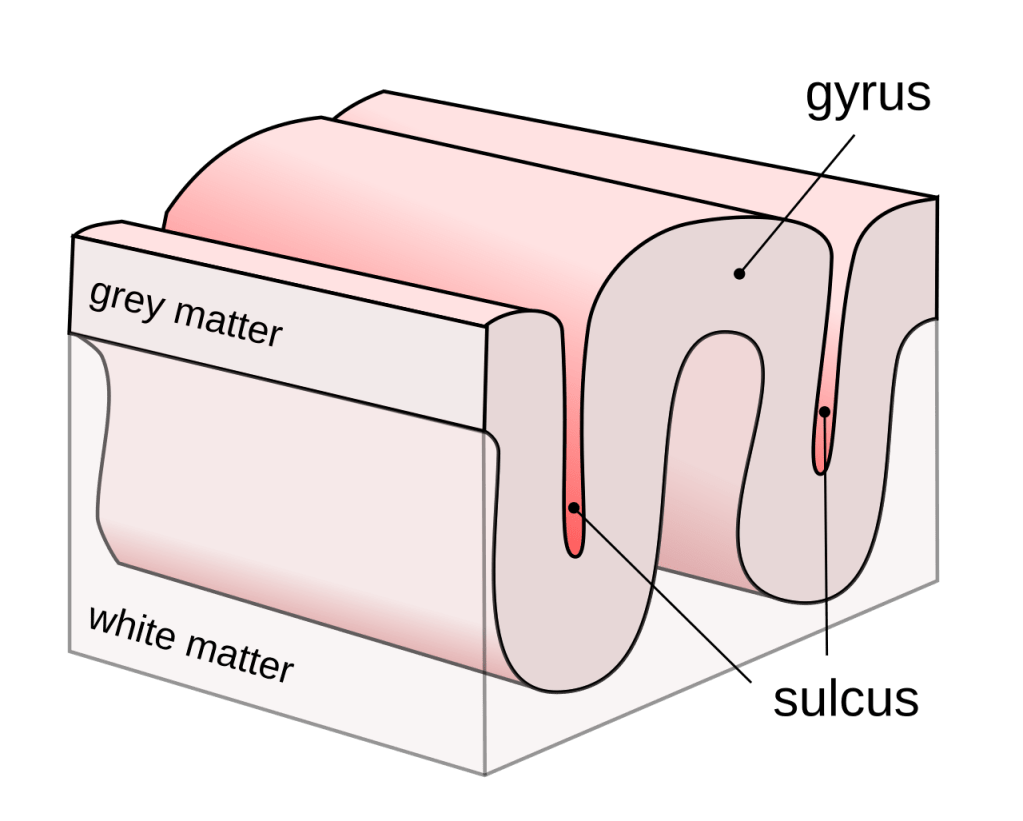

– Prunning the brain with the wisdom of the Heart

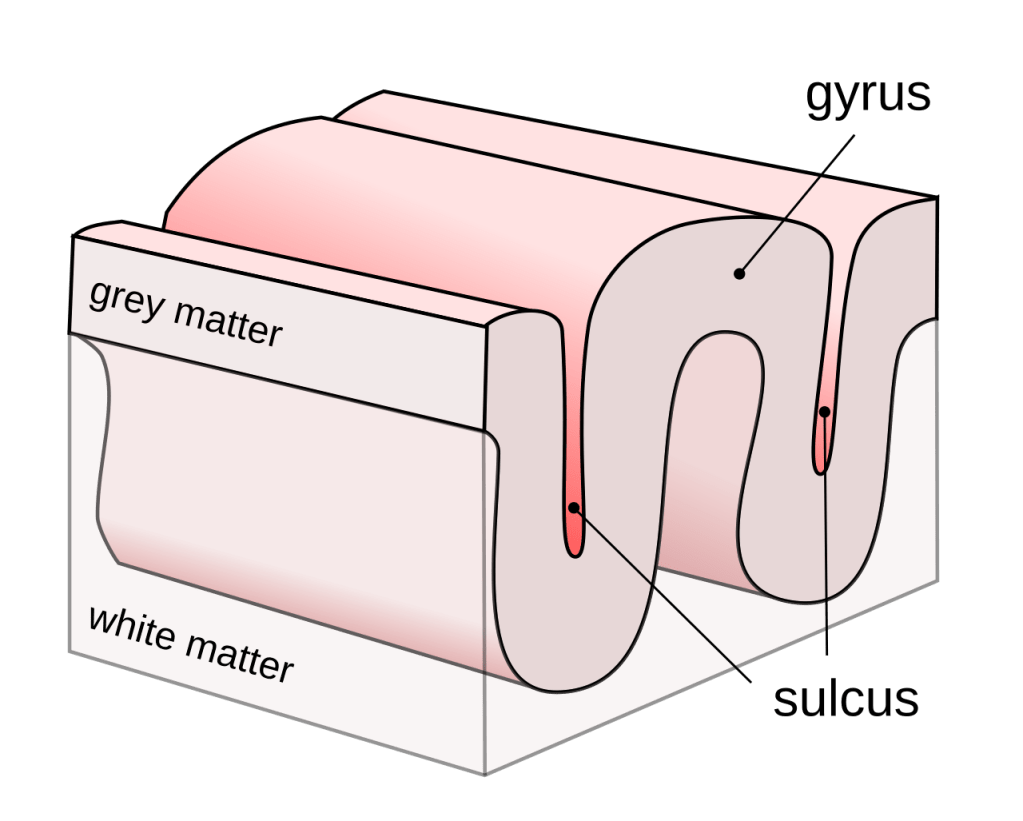

During infancy, billions of brain cells form connections with one another, blooming like a tree. Like a gardener trimming the excess branches, synaptic pruning clears away unneeded connections. Too much or too little pruning can contribute to a range of psychiatric disorders.

An inside look reveals the adult brain prunes its own branches

Did you know that when you’re born, your brain contains around 100 billion nerve cells? This is impressive considering that these nerve cells, also called neurons, are already connected to each other through an intricate, complex neural network that is essential for brain function.

Here’s how the brain does it. During development, neural stem cells produce neurons that navigate their way through the brain. Once at their destination, neurons set up shop and send out long extensions called axons and branched extensions called dendrites that allow them to form what are called synaptic connections through which they can communicate through electrical and chemical signals.

Studies of early brain development revealed that neurons in the developing brain go on overdrive and make more synaptic connections than they need. Between birth and early adulthood, the brain carefully prunes away weak or unnecessary connections, and by your mid-twenties, your brain has eliminated almost half of the synaptic connections you started out with as a baby.

This synaptic pruning process allows the brain to fine-tune its neural network and strengthen the connections between neurons that are important for brain function. It’s similar to how a gardener prunes away excess branches on fro0uit trees so that the resulting branches can produce healthier and better tasting fruit.

The brain can make new neurons

It was thought that by adulthood, this process of pruning excess connections between neurons was over. However, a new study from the Salk Institute offers visual proof that synaptic pruning occurs during adulthood similarly to how it does during development. The work was published today in the journal Nature Neuroscience, and it was funded in part by CIRM.

The study was led by senior author and Salk Professor Rusty Gage. Gage is well known for his earlier work on adult neurogenesis. In the late 90’s, he discovered that the adult brain can in fact make new neurons, a notion that overturned the central dogma that the brain doesn’t contain stem cells and that we’re born with all the neurons we will ever have.

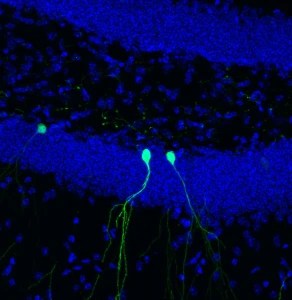

There are two main areas of the adult brain that harbor neural stem cells that can generate new neurons. One area is called the dentate gyrus, which is located in the memory forming area of the brain called the hippocampus. Gage and his team were curious to know whether the new neurons generated from stem cells in the dentate gyrus also experienced the same synaptic overgrowth and pruning that the neurons in the developing brain did.

Pruning the Adult Brain

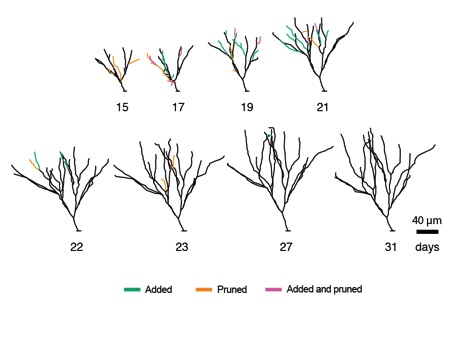

They developed a special microscope technique that allowed them to visually image the development of new neurons from stem cells in the dentate gyrus of the mouse brain. Every day, they would image the growing neurons and monitor how many dendritic branches they sent out.

Newly generated neurons (green) send out branched dendritic extensions to make connections with other neurons. (Image credit: Salk Institute) After observing the neurons for a few weeks, they were amazed to discover that these new neurons behaved similarly to neurons in the developing brain. They sent out dozens of dendritic branches and formed synaptic connections with other neurons, some of which were eventually pruned away over time.

This phenomenon was observed more readily when they made the mice exercise, which stimulated the stem cells in the dentate gyrus to divide and produce more neurons. These exercise-induced neurons robustly sent out dendritic branches only to have them pruned back later.

First author on the paper, Tiago Gonçalves commented on their observations:

“What was really surprising was that the cells that initially grew faster and became bigger were pruned back so that, in the end, they resembled all the other cells.”

Rusty Gage was also surprised by their findings but explained that developing neurons, no matter if they are in the developing or adult brain, have evolved this process in order to establish the best connections.

“We were surprised by the extent of the pruning we saw. The results suggest that there is significant biological pressure to maintain or retain the dendrite tree of these neurons.”

A diagram showing how the adult brain prunes back the dendritic branches of newly developing neurons over time. (Image credit: Salk Institute).

Potential new insights into brain disorders

This study is important because it increases our understanding of how neurons develop in the adult brain. Such knowledge can help scientists gain a better understanding of what goes wrong in brain disorders such as autism, schizophrenia, and epilepsy, where defects in how neurons form synaptic connections or how these connections are pruned are to blame.

Gonçalves also mentioned that this study raises another important question related to the regenerative medicine applications of stem cells for neurological disease.

“This also has big repercussions for regenerative medicine. Could we replace cells in this area of the brain with new stem cells and would they develop in the same way? We don’t know yet.”

Related Links: Adult brain prunes branched connections of new neurons

– Growth and pruning: the brain of a child

Translated by Rumia Bose

This post is a revised version of “Growth and pruning” published on 9-11-2017

A newborn baby is well-equipped to eat and sleep, but not much more than this. It cannot speak, can hardly see at all, and has but minimal voluntary controlled movements of its arms and legs. All this changes quite quickly. At one year of age, a child can see a lot, can direct the use of its arms and legs remarkably well, and makes its first attempts to walk and talk.

Previously it was believed that, at birth, the brain was ready for all these tasks (nature), and that the child only had to learn through experience (nurture). The brains of a newborn are however prepared for the tasks to come, but still need to grow. By adulthood they are two or three times as big. That growth is controlled by the genes and by experience, the interaction with the environment. The genes are most important in the first year of life; from here onwards the environment becomes increasingly important1.

Critical periods

A newborn baby can very quickly identify its mother; soon after that it also recognises her facial expressions. There are critical periods for everything a child learns. In this period he has to acquire the basic skills for that function. After the first year the critical period for basic visual functions – such as depth vision, colours and movement – are laid down in the brain. But if you were to leave a baby in the dark for its first year, then it would never learn to see well.

The more complicated the cognitive function, the longer it takes before it is fully developed, and the longer the critical period lasts. The critical period takes longest for executive functions such as goal-directed planning and impulse suppression. This lasts till beyond the first twenty years. These functions are essential for rational thinking and the modulation of urges and risky behaviour, and all these are therefore only fully established when one is past the age of twenty.

Growth….

What happens in a child’s brain during critical periods? At first the brain cells or neurones have few dendrites in the part of the cerebral cortex that accounts for that particular function. When the critical period starts, the dendritic trees grow and the number of interneuron connections increase. This is the time of growth. Later the number of interneuron connections reduces drastically. That is the period of pruning2.

Source: Gilmore JH, Knickmeyer RC, Gao W (2018): Imaging structural and functional brain development in early childhood. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 19:123-137.

During the period of growth of interneurone connections, the child learns all sorts of new skills, such as facial recognition. Learning and the growth of the cortex go hand in hand. Learning to see is facilitated by this growth, and the growth occurs as the child learns. A requirement for the latter is that the child is presented with new visual information. For instance, seeing the mother’s face often, but also other colourful moving objects.

The basic structure of the brain with the basic functions has been formed around the second year of life. This is especially the case for areas involved in perception or locomotion, such as the visual and motor cortex. The frontal cortex-which is of importance for rational thinking-takes a lot longer. The critical periods therefore correspond to the age at which growth and pruning takes place in the relevant areas of the cortex.

… and pruning

After a while the connections that are of little or no use are cleared away. The most important effect of this clearing is that the pruned cortex works far more efficiently. In order to recognise mother’s face quickly, all impressions that are somewhat similar have to be examined. Clearing away unimportant impressions results in a shorter search.

It is thought that the advantage of this process of growth and pruning is that it allows for a more flexible adjustment to the specific environment than a fully-programmed brain at birth, as seen in simpler forms of animal life, such as insects. The growth allows for fast, extensive and directed learning, while the subsequent pruning makes way for the most efficient application of what has been learnt.

Learning at a later age

All of this seems to suggest that the child can only acquire various skills such as seeing or language in its first years of life. This is naturally not true. Learning a language after five years of age is possible, of course, but it needs more effort, and one can almost never speak the language with the authentic native accents. Top musicians almost always start learning to play their instrument(s) of choice at a very young age3. The critical periods are especially important in learning basic skills, and not for learning subtle variations on a theme.

The critical period can even be “reopened” at a later age. Someone who has lost the ability to speak as a result of cerebral haemorrhage can learn to speak again if the damage is not too extensive. The lost skills of speech are then laid down in other areas of the cortex, mostly those adjacent to the damaged area4. This takes more effort than learning in childhood, but is essentially based on the same process of growth and pruning of neurones and interneuron connections.

- Bonsai Trees in Your Head: How the Pavlovian System Sculpts Goal-Directed Choices by Pruning Decision Trees

abstract

When planning a series of actions, it is usually infeasible to consider all potential future sequences; instead, one must prune the decision tree. Provably optimal pruning is, however, still computationally ruinous and the specific approximations humans employ remain unknown. We designed a new sequential reinforcement-based task and showed that human subjects adopted a simple pruning strategy: during mental evaluation of a sequence of choices, they curtailed any further evaluation of a sequence as soon as they encountered a large loss. This pruning strategy was Pavlovian: it was reflexively evoked by large losses and persisted even when overwhelmingly counterproductive. It was also evident above and beyond loss aversion. We found that the tendency towards Pavlovian pruning was selectively predicted by the degree to which subjects exhibited sub-clinical mood disturbance, in accordance with theories that ascribe Pavlovian behavioural inhibition, via serotonin, a role in mood disorders. We conclude that Pavlovian behavioural inhibition shapes highly flexible, goal-directed choices in a manner that may be important for theories of decision-making in mood disorders.

- The Heart: Threshold Between Two Worlds

Excerpted from The Knowing Heart, A Sufi Path of Transformation

Anyone who has probed the inner life to a certain extent, who has sat in silence long enough to experience the stillness of the mind behind its apparent noise, is faced with a mystery. Apart from all the outer attractions of life in the world, there exists at the heart of human consciousness something else, something quite satisfying and beautiful in itself, a beauty without features. The mystery is not so much that these two dimensions exist–an outer world and the mystery of the inner world–but that the human being is suspended between them–as a space in which both meet. It is as if the human being is the meeting point, the threshold between two worlds. Anyone who has explored this inwardness to a certain degree will know that it holds a great beauty and power. In fact, to be unaware of this mystery of inwardness is to be incomplete.

According to the great formulator of Sufi psychology, Al-Ghazalli:

There is nothing closer to you than yourself. If you don’t know your self, how will you know others? You might say, “I know myself,” but you are mistaken…. The only thing you know about your self is your physical appearance. The only thing you know about your inside (batin, your unconscious) is that when you are hungry you eat, when you are angry, you fight, and when you are consumed by passion, you make love. In this regard you are equal to any animal. You have to seek the reality within yourself…. What are you? Where have you come from and where are you going. What is your role in the world? Why have you been created? Where does your happiness life? If you would like to know yourself, you should know that you are created by two things. One is your body and your outer appearance (zahir) which you can see with your eyes. The other is your inner forces (batin). This is the part you cannot see, but you can know with your insight. The reality of your existence is in your inwardness (batin, unconscious). Everything is a servant of your inward heart.

In Sufism, “knowing” can be arranged in seven stages. These stages offer a comprehensive view of the various faculties of knowledge within which the heart comprises the sixth level of knowing:

1. Hearing about something, knowing what it is called. “Having a child is called ‘motherhood.’”

2. Knowing through the perception of the senses. “I have seen a mother and child with my own eyes.”

3. Knowing “about” something. “This is how it happens and what it is like to be a mother.”

4. Knowing through understanding and being able to apply that understanding. “I have a Ph.D. in mothering and my studies show…”

5. Knowing through doing or being something. “I am a mother.”

6. Knowing through the subconscious faculties of the heart. “It’s difficult to put into words everything a mother experiences and feels.”

7. Knowing through Spirit alone. This is much more difficult to describe and perhaps it’s foolhardy to try, but it may be something like this: “I am not a mother, but in the moment when all separation dissolves, I am you.”

The outer world of physical existence is perceived through the physical senses, through a nervous system that has been refined and purified by nature over millions of years. We can only stand in awe of this body’s perceptive ability.

On the other hand, the mystery of the inner world is perceived through other even subtler senses. It is these “senses” that allow us to experience qualities like yearning, hope, intimacy, or to perceive significance, beauty, and our participation in the unity.

When our awareness is turned away from the world of the senses, and away from the field of conventional human thoughts and emotions, we may find that we can sense an inner world of spiritual qualities, independent of the outer world.

Our modern languages lack precision when it comes to describing or naming that which can grasp the qualities and essence of this inner world. Perhaps the best word we have for that which can grasp the unseen world of qualities is “heart.” And what we understand by the word “heart” is an intelligence other than intellect, a knowing that operates at a subconscious level. The sacred traditions have sometimes delineated this subconscious knowing into various modes of knowing. What are known in some Sufi schools as the latifas (literally, the subtleties, al-lataif) are subtle subconscious faculties that allow us to know spiritual realities beyond what the senses or intellect can offer. This knowing is called subconscious, because what can be admitted into consciousness is necessarily limited and partial.

These latifas are sometimes worked on by carrying the energy of zhikr (remembrance) to precise locations in the chest and head in order to energize and activate these faculties. Once activated, they support and irradiate each other.

The five spiritual senses are connected.

They’ve grown from one root.

As one grows strong, the others strengthen, too:

each one becomes a cupbearer to the rest.

Seeing with the eye increases speech;

speech increases discernment in the eye.

As sight deepens, it awakens every sense,

so that perception of the spiritual

becomes familiar to them all.

When one sense grows into freedom,

all the other senses change as well.

When one sense perceives the hidden,

the invisible world becomes apparent to the whole.[Rumi, Mathnawi II, 3236-3241]

According to one model, the heart is understood as the totality of subtle, subconscious faculties; according to another model, it is the subtlest faculty of them all, sharing in all the knowledge of the others. Essentially, however, we can consider the heart a mostly subconscious knowing of spiritual realities or qualities.

A Universe of Qualities

The heart is the perceiver of qualities. What we mean by qualities are the modifiers of the things. If we say for instance that a certain book has a particular number of pages on a certain subject by a particular author, we have described its distinguishing outer characteristics. If we say, however, that the book is inspiring, depressing, boring, fascinating, profound, trivial, or humorous, we are describing qualities. Although qualities seem to be subjective and have their reality in an invisible world, they are more essential, more valuable, because they determine our relationship to a thing. Qualities modify things. But where do qualities originate if not in an inner world? And is that inner world completely subjective, contained within the individual brain? Or are qualities, somehow, the objective features of another “world,” another state of being?

The answer of the tradition is that Absolute Reality–which cannot be described or compared to anything–possesses qualities, or attributes. All of material existence manifests these qualities, but the qualities are prior to their manifestation in forms. Forms manifest the qualities of an inner world. A cosmic creativity is overflowing with its qualities which eventually result in the world of material existence.

The human being is an instrument of that cosmic creativity. The human heart is the mirror in which divine qualities and significances may appear. And the world is the mirror in which these qualities are reflected and known more clearly. The cosmic creativity manifests itself in and through the human heart which has the capacity for interpreting the forms and events of material existence.

From the point of view of the human being, qualities are projected on things, recognized in the outer world. Things lose or gain importance for us as they are qualified by qualities whose immediate source is the human heart, but whose ultimate source is the divine treasury. A cheap, mass-produced teddy-bear becomes an object of love because it has been qualified by the affection of a child’s heart.

This subject may seem elusive because we are so conditioned to project qualities onto the things and events of the world that we overlook that everything of true significance is happening within us. Furthermore, the qualities that we experience in relation to the outer, material world also have a reality beyond both ourselves and the things of outer world. That which becomes the object of our affection, for instance, is receiving a projection of the capacity for affection contained within the individual heart. Affection, itself, is a quality that exists in Reality itself and transcends both the heart and the object of affection. Another way of saying it is that we live in an affectionate universe and we know this through the relationship between the individual heart and the object of its affection.

A mature enlightenment is seeing all these projections for what they are: the heart, because of its nearness to the divine treasury, is primary; the world is the shadow. We need not then withdraw these qualities into ourselves, because the mirror of the world receiving the projection of the heart has received the qualities of the divine source. This divine source, the heart, and outer existence together form a unified Whole.

Between Ego and Spirit, Fragmentation and Wholeness

The heart could be called the child of the marriage of self and spirit. The heart occupies a position intermediate between ego and God. It becomes a point of contact between the two. Like a transformer, it receives the spiritualizing energy of the spirit and conveys it to the self. Like the physical heart it is the center of the individual psyche. If it is dominated by the demands of the ego-self, the heart is dead; it is not a heart at all. If it is receptive to spirit, then it can receive the qualities of spirit and distribute these according to its capacity to every aspect of the human being, and from the human being to the rest of creation. If it is receptive to spirit, a heart is sensitive, living, awake, whole. It becomes the treasury of God’s qualities.

In this, behold, there is indeed a reminder for everyone whose heart is wide-awake–that is who lends ear with conscious mind. [Qur’an 50:37]

It is through the heart that the completion of the human psyche is attained. The heart always has an object of love; it is always attracted to some sign of beauty. Whatever the heart holds its attention on, it will acquire its qualities. Those qualities are as much within the heart as within the thing that awakens those qualities in the heart. The situation is like two mirrors facing each other, while the original reflection comes from a third source. But one of these mirrors, the human heart, has some choice as to what it will reflect. Rumi said, “If your thought is a rose, you are the rose garden. If your thought is a thorn, you are kindling for the bath stove.”1 Being between the attractions of the physical world and the ego, on the one hand, and spirit and its qualities on the other, the heart is pulled from different sides. Rumi addressed this issue in a conversation recorded and presented in Fihi ma fihi2 (Herein is what is herein):

All desires, affections, loves, and fondnesses people have for all sorts of things, such as fathers, mothers, friends, the heavens and the earth, gardens, pavilions, works, knowledge, food, and drink–one should realize that every desire is a desire for food, and such things are all “veils.” When one passes beyond this world and sees that King without these “veils,” then one will realize that all those things were “veils” and “coverings” and that what they were seeking was in reality one thing. All problems will then be solved. All the heart’s questions and difficulties will be answered, and everything will become clear. God’s reply is not such that He must answer each and every problem individually. With one answer all problems are solved.3

There are countless attractions in the world of multiplicity. Whatever we give our attention to, whatever we hold in this space of our presence, its qualities will become our qualities. If we give the heart to multiplicity, the heart will be fragmented and dispersed. If we give the heart to spiritual unity, the heart will be unified.

Ultimately what the heart desires is unity in which it finds peace.

Truly, in the remembrance of God hearts find peace.

The ego desires multiplicity and suffers the fragmentation caused by the conflicting attractions of the world. Rabi’a, perhaps the greatest woman saint of the Sufi tradition, said, “I am fully qualified to work as a doorkeeper, and for this reason: What is inside me, I don’t let out. What is outside me, I don’t let in. If someone comes in, he goes right out again– He has nothing to do with me at all. I am a doorkeeper of the heart, not a lump of wet clay.”4 We can assume the responsibility of being the doorkeeper of our own heart, choosing what we wish to keep within the intimate space of our own being.

Purity of Heart

The heart is our deepest knowing. Sometimes that deepest knowing is veiled, or confused by more superficial levels of the mind: by opinions, by desires, by social conditioning, and most of all by fear. Like a mirror it may become obscured the veils of conditioned thought, by the soot of emotions, by the corrosion of negative attitudes. In fact we easily confuse the ego with the heart. Sometimes, in the name of following our hearts, we actually follow the desires and fears of the ego.

The heart may be sensitive or insensitive, awake or asleep, healthy or sick, whole or broken, open or closed. In other words, its perceptive ability will depend on its capacity and condition.

Both spirit and the world compete to win the prize of the human heart. As Junayd said, “The heart of the friend of God is the site of God’s mystery, and God does not reveal his mysteries in the heart of one who is preoccupied with the world.”5 The traditional teachers agree that one of the consequences of preoccupation with the world is the death of the heart. If the heart assumes the qualities of whatever attracts it, its attraction to the dense matter of the world only results at best in a limited reflection of the divine reality. At worst, the heart’s involvement with the purely physical aspects of existence results in the familiar compulsions of ego: sex, wealth, and power.

In The Alchemy of Happiness, Al-Ghazzali describes the human being in the following metaphor:

The body is like a country. The artisans are like the hands, feet, and various parts of the body. Passion is like the tax collector. Anger or rage is like the sheriff. The heart is the king. Intellect is the prime minister. Passion, like a tax collector using any means, tries to extract everything. Rage and anger are severe, harsh and punishing like the police and want to destroy or kill. The ruler not only needs to control passion and rage, but also the intellect and must keep a balance among all these forces. If the intellect becomes dominated by passion or anger, the country will be in ruin and the ruler will be destroyed.

Rumi echoes the same theme when he describes the role of Conscious Reason in keeping a balance among our various desires:

God has given you Conscious Reason

as an instrument for polishing the heart until its surface reflects.

But you, prayerless, have bound the polisher

and freed the two hands of sensuality.

If you can restrain sensuality, you will free the polisher….

Until now you have made the water turbid, but no more.

Do not stir it up, let the water become clear enough

for the moon and stars to be reflected in it.

For the human being is like the water of a river:

when muddied you cannot see the bottom.

The river is full of jewels and pearls.

Do not cloud the water that was pure and free.

[Mathnawi IV, 2475-2477, 2480-2482]

The attractions of the outer world are only a small distraction compared to the promptings of egoism which distract us from within. Bayazid Bistami said, “The contraction of the heart comes with the expansion of the ego, and vice versa.”

When our hearts soften at the remembrance of God [39:23], the ego acquires the qualities of servanthood and humility in relation to the Divine Majesty, and the heart becomes sensitive and expansive–expansive enough, in fact, to contain the whole universe.6

The healthy heart requires the nourishment of spiritual foods. When the heart is healthy, its desires will be healthy. Muhammad said, “The heart of the faithful is the throne of the Merciful.” When the heart has nourished itself only on the desires of physical existence, it is deprived of life-giving nourishment, and its own desires become less sound, more sickly.

Sufi wisdom offers several traditional cures for an ailing heart. One of these is the contemplating the meanings of the revealed Holy Books and the words of the saints, since these perform an action upon the heart, removing its illusions, healing its ills, restoring its strength.

Another cure for the heart is keeping one’s stomach empty. Muhammad said that an excess of food hardens the heart. Fasting is the opposite of the addictions, subtle and not so subtle, with which he numb ourselves to the heart’s pain. When through fasting we expose the heart’s pain to ourselves, we become more emotionally vulnerable and honest. Only then can the heart can be healed.

Keeping a night vigil until dawn is a practice that is unfamiliar outside of Islamic culture, but it has been a mainstay of the Sufis. It has been said that in the early hours before the dawn “the angels draw near to the earth,” and our prayers can better be answered. Another explanation is that in these early morning hours the activity of the world has been reduced to its minimum, the psychic atmosphere has become still, and we are more able to reach the depths of concentration upon our own unconscious.

Finally, keeping the company of those who are conscious of God can restore faith and health to the heart. “The best among you are those who when seen remind you of God.”7