- Allegory of Folly,

In the early sixteenth century when Quentin Matsys painted his Allegory of Folly, likely around 1510, fools were still commonly found at court or carnivals, performing in morality plays. Sometimes a fool would be mentally handicapped, to be mocked for the amusement of the general public. Matsys has chosen to represent his fool with a wen, a lump on the forehead, which was believed to contain a “stone of folly” responsible for stupidity or mental handicap. In other instances, however, the fool would be a clever and astute observer of human nature, a comedian who used the fool’s robes as a pretext for satire and ridicule. Matsys’s fool was nearly an exact contemporary of Erasmus’ Praise of Folly, in which the character of Folly is in fact a wise and astute commentator on folly in others. Fools were a popular subject in both the art and literature of this era and Erasmus’ work was particularly important to the sixteenth-century Humanist circles in Antwerp.

In the early sixteenth century when Quentin Matsys painted his Allegory of Folly, likely around 1510, fools were still commonly found at court or carnivals, performing in morality plays. Sometimes a fool would be mentally handicapped, to be mocked for the amusement of the general public. Matsys has chosen to represent his fool with a wen, a lump on the forehead, which was believed to contain a “stone of folly” responsible for stupidity or mental handicap. In other instances, however, the fool would be a clever and astute observer of human nature, a comedian who used the fool’s robes as a pretext for satire and ridicule. Matsys’s fool was nearly an exact contemporary of Erasmus’ Praise of Folly, in which the character of Folly is in fact a wise and astute commentator on folly in others. Fools were a popular subject in both the art and literature of this era and Erasmus’ work was particularly important to the sixteenth-century Humanist circles in Antwerp.

The traditional costume of the fool includes a hooded cape with the head of a cock and the ears of an ass, as well as bells, here attached to a red belt. The fool holds a staff known as a marotte, or bauble, topped with a small carved figure of another fool – himself wearing the identifying cap. This staff would have been used as a puppet for satirical skits or plays, and the figure’s obscene gesture of dropping his trousers, symbolic of the insults associated with fools, was once overpainted by a previous owner who found it overly shocking.

The gesture of silence, with the fool holding a finger to his lips, refers to the Greek god of silence, Harpocrates, who was generally depicted in this manner. Silence was considered a virtue associated with wise men such as philosophers, scholars, or monks. Here, however, Matsys turns the gesture into a parody by juxtaposing it with the inscription ‘Mondeken toe’, meaning ‘keep your mouth shut’, beneath the crowing cock’s head. Matsys is drawing our attention to the Fool’s indiscretion. A later hand has added the word ‘Mot’ above, likely a later sixteenth or seventeenth century reference to a prostitute – this may have been an attempt to turn the present allegory into the figure of a procuress.

Matsys’ fool is made even more grotesque by his hideous deformities – an exaggerated, beaked nose and hunched back – and thin-lipped, toothless smirk. Grotesque figures were a favourite theme of the artist, making regular appearances in his paintings as tormenters of Christ or in allegories of Unequal Lovers. This reflects an awareness of the grotesque head studies of Leonardo da Vinci, whose drawings had made their way northward from Italy. Indeed, of all Matsys’s other works, the fool in the present painting is perhaps closest in type to the tormenter directly behind and to the right of Christ in the Saint John Altarpiece – which is, itself, a direct quotation from Leonardo’s own drawing of Five Grotesque Heads.

Quinten Matsys’ early training is a matter of speculation, with scholars suggesting variously that he may have been apprenticed in Antwerp to Dieric Bouts; trained as a miniaturist in his mother’s native town of Grobbendonk; or possibly worked for Hans Memling’s studio in Bruges. We do know for certain that in 1494, Matsys was admitted to the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke as a master painter, and by the end of the century he was operating his own studio with several apprentices, among them his sons Cornelis and Jan. Matsys is known for both religious and secular works, and his style became increasingly Italianate in his later career; in turn he is recognized as an influence on such painters as Joos van Cleve, Joachim Patinir and Lucas Cranach the Elder.

- Folly ’s ‘keep your mouth shut’, Anno 2020

Based on economic growth, financial hegemony of the “happy few”” and abuse or rape of cheapest labor workers in Low-cost country or homeland, the democracy of Modern man shall never succeed to recover his soul with fake “sincere political change” or with fake “concern”.

Folly ’s ‘keep your mouth shut’ about all the abuses of the systems and is silent about Ethics, Virtues and uprightness… Silence about spiritual grow, honesty and respect of differents communities…

Prophets of doom now abound and “green parties” have mushroomed everywhere. The moving force for those movements remains, however, by and large purely external. For a humanity turned towards outwardness by the very processes of modernization, it is not so easy to see that the blight wrought upon the environment is in reality an externalization of the destitution of the inner state of the soul of that humanity whose actions are responsible for the ecological crisis.

Many claim, for example, that if we could only change our means of transportation and diminish the use of fossil fuels as a source of energy, the problem would be solved or at least ameliorated. Few ask, however, why it is that modern man feels the need to travel so much?

The wisdom of the 21th century or the Foffy of our times say: ‘keep your mouth shut’,

But can we ask Why?

Ship of Fools

Ship of Fools

-Why is the domicile of much of humanity so ugly and life so boring that the type of man most responsible for the environmental crisis has to escape the areas he has helped to vilify and take his pollution with him to the few still well-preserved areas of the earth in order to continue to function?

-Why must modern man consume so much and satiate his so-called needs only outwardly?

-Why is he unable to draw from any inward sustenance?

We are, needless to say, not opposed to better care of the planet through the use of wiser means of production, transportation, etc. than those which exist today. Alternative forms of technology are to be welcomed . But such feats of science and engineering alone will not solve the problem.

There is no choice but to answer these and similar questions and to bring to the fore the spiritual dimension and the historical roots of the ecological crisis which many refuse to take into consideration to this day.

Democracy:

Oligarchy then degenerates into a democracy where freedom is the supreme good but freedom is also slavery. In democracy, the lower class grows bigger and bigger. The poor become the winners. People are free to do what they want and live how they want. People can even break the law if they so choose. This appears to be very similar to anarchy.

Plato uses the “democratic man” to represent democracy. The democratic man is the son of the oligarchic man. Unlike his father, the democratic man is consumed with unnecessary desires. Plato describes necessary desires as desires that we have out of instinct or desires that we have to survive. Unnecessary desires are desires we can teach ourselves to resist such as the desire for riches. The democratic man takes great interest in all the things he can buy with his money. Plato believes that the democratic man is more concerned with his money over how he can help the people. He does whatever he wants when ever he wants to do it. His life has no order or priority. So can a happy few ( 1% of the world population) try to dictate the rest of the human and using them as robotic slaves and wanting them to live without a soul.

- Vandana Shiva On the Real Cause of World Hunger

Oneness vs. The 1%: #VandanaShiva at the United Nations Office at Geneva.

- Technocracy: Amazon, Google, and Apple have moved past monopoly status to competing directly with governments… and winning

Amazon’s cloud servers host the CIA, the Department of Homeland Security, the Defense Department, and other US agencies, for example

US Senator Josh Hawley is demanding a criminal antitrust probe of Amazon as the e-commerce behemoth’s powers grow to rival the government’s own. Google and Apple, too, are now ordering governments around.

Amazon “abuses its position as an online platform and collects detailed data about merchandise so Amazon can create copycat products under an Amazon brand,” Hawley charged in a letter he sent to US Attorney General William Barr on Tuesday. The senator (R-MO) demanded a criminal probe of the e-commerce giant, accusing it of engaging in “predatory and exclusionary data practices to build and maintain a monopoly” – a textbook violation of antitrust law.

Charging that Amazon has gained unprecedented monopoly power through the sheer wealth of data it has collected on its users, allowing it to clone sellers’ products and undercut them on price, the senator likened the company’s “capacity for data collection” to “a brick and mortar retailer attaching a camera to every customer’s forehead.” With the coronavirus pandemic forcing the lion’s share of commerce online, Amazon has assumed near-omnipotence.

Even if all of Hawley’s allegations – derived from a Wall Street Journal investigation published earlier this month – are proven 100 percent true, it’s questionable whether the Justice Department would be willing (or able) to punish Amazon.

In some ways, the company is at least as powerful as the government whose laws it goes through the motions of obeying. Amazon’s cloud servers host the CIA, the Department of Homeland Security, the Defense Department, and other US agencies, meaning if the company decided to throw a temper tantrum in response to legal penalties (as it threatened to do in France) government operations could be severely disrupted.

Indeed, after losing the lucrative Pentagon JEDI contract to competitor Microsoft, it was Amazon that hauled the Trump administration into court and may yet force it to reconsider. If the trillion-dollar company can scupper the plans of the White House, another antitrust probe (several are already underway) is unlikely to correct its behavior.

Google and Apple, too, have grown so large and powerful they can not only compete with governments, but bend them to their will. Germany was forced on Sunday to scrap its plans for an open-source privacy-prioritizing contact-tracing system (the so-called Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing platform) after Apple refused to make changes to its iOS operating system that would have allowed public health apps built on the platform to access Bluetooth data from a central server.

Apple, which is working on its own decentralized contact-tracing platform in conjunction with fellow tech behemoth Google, refused to make the change, locking horns with the German government – supposedly in the name of user privacy. The Apple-Google platform logs contact data on users’ devices, rather than a central server, keeping it theoretically under users’ control, as well as under Apple’s and Google’s.

While it’s nice to think these mega-corporations genuinely care about users’ privacy, Apple’s objection to the German government’s demands was almost certainly motivated by market considerations. Google and Apple have insisted their decentralized platform will come with all the privacy protections a concerned user could want, but both companies’ dismal privacy records cast doubt on such promises.

A central server controlled by the German government would have deprived Apple and Google of the user data that is their lifeblood – clearly an unacceptable scenario for the trillion-dollar companies. Faced with such powerful opposition, a German government source told Reuters there was “no alternative but to change course.”

Opponents of the German system warned that centralization of data would permit “unprecedented surveillance of society at large” – a very real and valid concern. But is placing that same wealth of data in the hands of the private sector – in Germany or in the US – really preferable? Big Tech may be eager and willing to assume the mantle of Big Brother, but those on the receiving end of a heavy-handed surveillance state are unlikely to care whether it’s the public or private sector doing the oppressing.

Data centers can be thought of as the “brains” of the internet. Their role is to process, store, and communicate the data behind the myriad information services we rely upon every day, whether it be streaming video, email, social media, online collaboration, or scientific computing.

Data centers utilize different information technology (IT) devices to provide these services, all of which are powered by electricity. Servers provide computations and logic in response to information requests, while storage drives house the files and data needed to meet those requests. Network devices connect the data center to the internet, enabling incoming and outgoing data flows. The electricity used by these IT devices is ultimately converted into heat, which must be removed from the data center by cooling equipment that also runs on electricity.

On average, servers and cooling systems account for the greatest shares of direct electricity use in data centers, followed by storage drives and network devices (Figure 1). Some of the world’s largest data centers can each contain many tens of thousands of IT devices and require more than 100 megawatts (MW) of power capacity—enough to power around 80,000 U.S. households (U.S. DOE 2020).

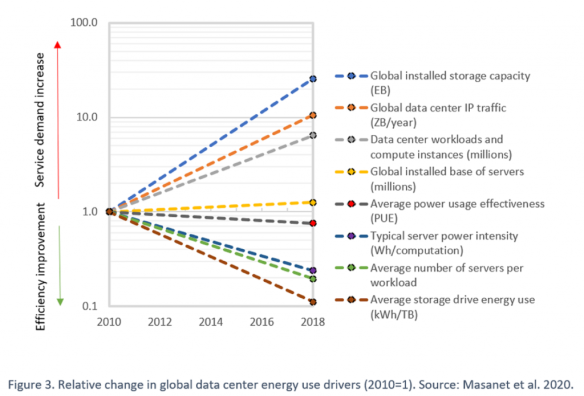

As the number of global internet users has grown, so too has demand for data center services, giving rise to concerns about growing data center energy use. Between 2010 and 2018, global IP traffic—the quantity of data traversing the internet—increased more than ten-fold, while global data center storage capacity increased by a factor of 25 in parallel (Masanet et al. 2020). Over the same time period, the number of compute instances running on the world’s servers—a measure of total applications hosted—increased more than six-fold (see Figure 3) (Masanet et al. 2020).

These strong growth trends are expected to continue as the world consumes more and more data. And new forms of information services such as artificial intelligence (AI), which are particularly computationally-intensive, may accelerate demand growth further. Therefore, the ability to quantify and project data center energy use is a key energy and climate policy priority.

- The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times

The Reign of Quantity gives a concise but comprehensive view of the present state of affairs in the world, as it appears from the point of view of the ‘ancient wisdom’, formerly common both to the East and to the West, but now almost entirely lost sight of. The author indicates with his fabled clarity and directness the precise nature of the modern deviation, and devotes special attention to the development of modern philosophy and science, and to the part played by them, with their accompanying notions of progress and evolution, in the formation of the industrial and democratic society which we now regard as ‘normal’. Read more here

- Modern times: Crucifying Christ every day

A lifelong pilgrimage. The Mirror of Jheronimus bosch for our times:

A lifelong pilgrimage. The Mirror of Jheronimus bosch for our times:

The figure of the wayfarer – both on the outside panels of the two versions of the Haywain Triptych and the now octagonal panel in Rotterdam – shows an image of allegorical texts in which the whole of human existence is conceived as a pilgrimage. This stems from a powerful Middle Ages tradition that can be seen, for example, in the Middle Netherlands publication entitled Boeck van den pelgherym (Book of the Pilgrim),by Jacob Bellaert which appeared in Haarlem in 1486.

This book explicitly laid down the notion that all people are pilgrims on their way to a heavenly Jerusalem. Bosch, however, did not portray his wayfarer as a stereotypical pilgrim, with all the well-known attributes that would characterize him as such.

Indeed, Bosch did refer to plodding, and thus to the idea of humanity making a pilgrimage. Every person as a devoted believer must find his or her own way with God’s help. For this purpose the traveller is equipped with a number ofpractical attributes, such as a strong staff, which is at the same time symbolic. The painter did not portray this staff as the typical long pilgrim’s staff, but as club-like stick with which the marching traveller wards off the threatening dog.

Bosch seems literally to have painted a passage from the Middle Netherlands adaptation of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis (The mirror of human salvation): in many places the pilgrim must journey along back roads and needs a stick to ward off threatening dogs. The staff symbolizes the belief that humanity offers a footing not to stray from the righteous way, and serves him as a weapon.

Bosch’s travelling man has packed his belongings in the big basket on his back and carries this earthly burden along the path of life. He must lead his life in imitation of Christ; he must bear His burdens, contemplating His example from hour to hour and from day to day. Bosch’s interpretation of the toiling wayfarer is established by the title page of an early printed edition of Thomas van Kempen’s famous book De Navolging van Christus (The Imitation of Christ), Antwerp 1505.

If we are not doing that we are then Crucifying Christ every day of our modern times. See polishing your Heart

If we are not doing that we are then Crucifying Christ every day of our modern times. See polishing your Heart

Christ Carrying the Cross (Bosch, Ghent)

The work depicts Jesus carrying the cross above a dark background, surrounded by numerous heads, most of which are characterized with grotesque faces. There are a total of eighteen portraits, plus one on Veronica’s veil. Jesus has a woeful expression, his eyes are closed and the head is reclinating.

The work depicts Jesus carrying the cross above a dark background, surrounded by numerous heads, most of which are characterized with grotesque faces. There are a total of eighteen portraits, plus one on Veronica’s veil. Jesus has a woeful expression, his eyes are closed and the head is reclinating.

In the bottom right corner is the impenitent thief, who sneers against three men who are mocking him. The penitent thief is at top right: he is portrayed with very pale skin, while being confessed by a horribly ugly monk.

The bottom left corner shows Veronica with the holy shroud, with her eyes half-open and the face looking back. Finally, at the top left is Simon of Cyrene, his face upside upturned.

While surrounded by the mob in caricature Christ is accompanied by Simon of Cyrene, St. Veronica and the Good and Bad Thieves. Veronica holds the imprinted face of Christ on her veil. The two faces of Jesus contrast sharply with the horrible faces around them. Bosch imbues the mob with faces of sin. Here humanity is ugly and full of evil. They externally bear the marks of their inner torment, as contrasted with the serene faces of Jesus and Veronica. José de Sigüenza, a 16th-century Spanish author, wrote: “The difference between the work of Bosch and that of other painters lies in the fact that the others depict man as he appears on the outside. Only Bosch dared to paint him the way he is on the inside.”

While surrounded by the mob in caricature Christ is accompanied by Simon of Cyrene, St. Veronica and the Good and Bad Thieves. Veronica holds the imprinted face of Christ on her veil. The two faces of Jesus contrast sharply with the horrible faces around them. Bosch imbues the mob with faces of sin. Here humanity is ugly and full of evil. They externally bear the marks of their inner torment, as contrasted with the serene faces of Jesus and Veronica. José de Sigüenza, a 16th-century Spanish author, wrote: “The difference between the work of Bosch and that of other painters lies in the fact that the others depict man as he appears on the outside. Only Bosch dared to paint him the way he is on the inside.”

This dramatic panel is “one of the most hallucinatory creations of the history of Western art”, in the words of Bosch expert Paul van den Broeck.

A reminder, most of the paintings by Bosch are religious, but at the same time, they ar e a critical analysis of the world and its human inhabitants. Bosch often does that in a highly ingenious way. This Christ Carrying the Cross demonstrates how deeply Bosch felt and identified with the suffering of Christ. This empathy fits in with the teachings of the late-medieval devotional movements from Bosch’s time, which saw Jesus as a lonely and resigned man who conquered the sins of the ugly and even bestial world all on his own. For Bosch Christ is the one to follow because He alone can forgive our ugliness (sin) and call us to a new beauty (grace.) . This is the message Bosch wanted to convey here.

e a critical analysis of the world and its human inhabitants. Bosch often does that in a highly ingenious way. This Christ Carrying the Cross demonstrates how deeply Bosch felt and identified with the suffering of Christ. This empathy fits in with the teachings of the late-medieval devotional movements from Bosch’s time, which saw Jesus as a lonely and resigned man who conquered the sins of the ugly and even bestial world all on his own. For Bosch Christ is the one to follow because He alone can forgive our ugliness (sin) and call us to a new beauty (grace.) . This is the message Bosch wanted to convey here.

Bosch places the head of Christ at the crossing of two diagonal composition lines. One diagonal follows the beam of the Cross, from the head of Simon of Cyrene, the man who helped to carry Christ’s Cross, to the “bad thief” at the bottom right, who was crucified beside Christ. The second diagonal runs from the bottom left, with Veronica’s sudarium, to the pallid face of the “good thief” in the upper-right corner. He has the dubious pleasure of the company of a physician – or is it a Pharisee? – and a monk.

Bosch places the head of Christ at the crossing of two diagonal composition lines. One diagonal follows the beam of the Cross, from the head of Simon of Cyrene, the man who helped to carry Christ’s Cross, to the “bad thief” at the bottom right, who was crucified beside Christ. The second diagonal runs from the bottom left, with Veronica’s sudarium, to the pallid face of the “good thief” in the upper-right corner. He has the dubious pleasure of the company of a physician – or is it a Pharisee? – and a monk.

Drawing on our walk with Christ in the Ghent Christ Carrying the Cross, it may be good to paraphrase the ancient prayer to Santiago de Compostela:

Be for us our companion on our daily walks,

Our guide at the crossroads,

Our breath in our weariness,

Our protection in danger,

Our shelter on the way,

Our shade in the heat,

Our light in the darkness,

Our consolation in our discouragements,

And our strength in our intentions.

The iconography of the Passion scenes which Bosch painted during his middle and later years are simpler than that of his earlier paintings, their imagery more easily grasped by the viewer. One such work is the Christ Carrying the Cross in the Palacio Real, Madrid. Christ dominates the foreground, almost crushed beneath the heavy Cross which the elderly Simon of Cyrene struggles to lift from his back. The ugly heads of his executioners rise steeply in a mass towards the left;

The iconography of the Passion scenes which Bosch painted during his middle and later years are simpler than that of his earlier paintings, their imagery more easily grasped by the viewer. One such work is the Christ Carrying the Cross in the Palacio Real, Madrid. Christ dominates the foreground, almost crushed beneath the heavy Cross which the elderly Simon of Cyrene struggles to lift from his back. The ugly heads of his executioners rise steeply in a mass towards the left;

in the distance, the sorrowing Virgin collapses into the arms of John the Evangelist. Whereas Bosch’s earlier composition of this subject in Vienna had been diffuse and primarily narrative, the Madrid version is concentrated, and the way that Christ ignores his captors to look directly at the spectator gives it the quality of a timeless devotional image.

in the distance, the sorrowing Virgin collapses into the arms of John the Evangelist. Whereas Bosch’s earlier composition of this subject in Vienna had been diffuse and primarily narrative, the Madrid version is concentrated, and the way that Christ ignores his captors to look directly at the spectator gives it the quality of a timeless devotional image.

Walter S. Gibson in his work on Bosch states that some critics claim that Bosch equated the historical tormenters of Christ with humankind at large whose daily wickedness continues to torture Christ after his Resurrection. This concept of ‘Perpetual Passion’ was not uncommon in Bosch’s day. But is this what the face of Jesus is saying? Could it not be less an accusation and more an appeal to the viewer found within Matthew 16:24: ‘If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me”?

Look here for A lifelong pilgrimage: The Mirrors of Jheronimus bosch

see also THE “RENEWING OF CREATION AT EACH INSTANT”

- In Praise of Folly by Erasmus

In Praise of Folly, also translated as The Praise of Folly (Latin: Stultitiae Laus or Moriae Encomium; Greek title: Μωρίας ἐγκώμιον (Morias enkomion); Dutch title: Lof der Zotheid), is an essay written in Latin in 1509 by Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam and first printed in June 1511. Inspired by previous works of the Italian humanist Faustino Perisauli De Triumpho Stultitiae, it is a satirical attack on superstitions and other traditions of European society as well as on the Western Church.

In Praise of Folly, also translated as The Praise of Folly (Latin: Stultitiae Laus or Moriae Encomium; Greek title: Μωρίας ἐγκώμιον (Morias enkomion); Dutch title: Lof der Zotheid), is an essay written in Latin in 1509 by Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam and first printed in June 1511. Inspired by previous works of the Italian humanist Faustino Perisauli De Triumpho Stultitiae, it is a satirical attack on superstitions and other traditions of European society as well as on the Western Church.

Erasmus revised and extended his work, which was originally written in the space of a week while sojourning with Sir Thomas More at More’s house in Bucklersbury in the City of London.[1] The title Moriae Encomium had a punning second meaning as In Praise of More.

In Praise of Folly starts off with a satirical learned encomium, in which Folly praises herself, after the manner of the Greek satirist Lucian, whose work Erasmus and Sir Thomas More had recently translated into Latin, a piece of virtuoso foolery; it then takes a darker tone in a series of orations, as Folly praises self-deception and madness and moves to a satirical examination of pious but superstitious abuses of Catholic doctrine and corrupt practices in parts of the Roman Catholic Church—to which Erasmus was ever faithful—and the folly of pedants. Erasmus had recently returned disappointed from Rome, where he had turned down offers of advancement in the curia, and Folly increasingly takes on Erasmus’ own chastising voice. The essay ends with a straightforward statement of Christian ideals. “No Man is wise at all Times, or is without his blind Side.”

In Praise of Folly starts off with a satirical learned encomium, in which Folly praises herself, after the manner of the Greek satirist Lucian, whose work Erasmus and Sir Thomas More had recently translated into Latin, a piece of virtuoso foolery; it then takes a darker tone in a series of orations, as Folly praises self-deception and madness and moves to a satirical examination of pious but superstitious abuses of Catholic doctrine and corrupt practices in parts of the Roman Catholic Church—to which Erasmus was ever faithful—and the folly of pedants. Erasmus had recently returned disappointed from Rome, where he had turned down offers of advancement in the curia, and Folly increasingly takes on Erasmus’ own chastising voice. The essay ends with a straightforward statement of Christian ideals. “No Man is wise at all Times, or is without his blind Side.”

The essay is filled with classical allusions delivered in a style typical of the learned humanists of the Renaissance. Folly parades as a goddess, offspring of Plutus, the god of wealth and a nymph, Freshness. She was nursed by two other nymphs, Inebriation and Ignorance. Her faithful companions include Philautia (self-love), Kolakia (flattery), Lethe (forgetfulness), Misoponia (laziness), Hedone (pleasure), Anoia (dementia), Tryphe (wantonness), and two gods, Komos (intemperance) and Nigretos Hypnos (heavy sleep). Folly praises herself endlessly, arguing that life would be dull and distasteful without her. Of earthly existence, Folly pompously states, “you’ll find nothing frolic or fortunate that it owes not to me.” Read here the Praise of Folly

The essay is filled with classical allusions delivered in a style typical of the learned humanists of the Renaissance. Folly parades as a goddess, offspring of Plutus, the god of wealth and a nymph, Freshness. She was nursed by two other nymphs, Inebriation and Ignorance. Her faithful companions include Philautia (self-love), Kolakia (flattery), Lethe (forgetfulness), Misoponia (laziness), Hedone (pleasure), Anoia (dementia), Tryphe (wantonness), and two gods, Komos (intemperance) and Nigretos Hypnos (heavy sleep). Folly praises herself endlessly, arguing that life would be dull and distasteful without her. Of earthly existence, Folly pompously states, “you’ll find nothing frolic or fortunate that it owes not to me.” Read here the Praise of Folly

In The Manual of a Christian Knight [1501]

Desiderius Erasmus was a Catholic priest and theologian who clearly had Christ in mind when he penned it in 1501. Although it is over 500 years old, I hope you will appreciate the relevance today of these 22 rules in Erasmus’ Manual of a Christian Knight.

The mortal world a field is of battle

Which is the cause that strife doth never fail

Against man, by warring of the flesh

With the devil, that always fighteth fresh

The spirit to oppress by false envy;

The which conflict is continually

During his life, and like to lose the field.

But he be armed with weapon and shield

Such as behoveth to a christian knight,

Where God each one, by his Christ chooseth right

Sole captain, and his standard to bear.

Who knoweth it not, then this will teach him here

In his brevyer, poynarde, or manual

The love shewing of high Emanuell.

In giving us such harness of war

Erasmus is the only furbisher

Scouring the harness, cankered and adust

Which negligence had so sore fret with rust

Then champion receive as thine by right

The manual of the true christian knight.

– Desiderius Erasmus

Here some of the 22 rules:

- We must watch and look about us evermore while we be in this life.

- Of the weapons to be used in the war of a Christian man.

- That the first point of wisdom is to know thyself, and of two manner wisdoms, the true wisdom, and the apparent.

- Of the outward and inward man.

- Of the diversity of affections.

- Of the inward and outward man and of the two parts of man, proved by holy scripture.

- Of three parts of man, the spirit, the soul, and the flesh.

- Certain general rules of true christian living.

- Against the evil of ignorance.

- Jordi Savall talks about his Erasmus project