The Continuous Line: The History and Roots of an Ancient Art Form

A drawing is simply a line going for a walk.

— Paul Klee

Introduction

Most art students discover or are taught the simple technique of the continuous-line drawing. There is something magical and physically satisfying in the creation of a complete image from a single line. The technique requires little training. Place the drawing instrument on the paper and don’t lift it until the drawing is complete. Ideally, the line ends where it begins without any additions but small details, such as eyes, which can be added later to complete the work.

This paper will examine the history of this technique which is one of man’s oldest art forms, related to string figures (Cats’ Cradles) and more distantly to motifs such as the labyrinth. As with most ancient designs, it carries a deeper meaning which must be teased from the many and varied examples that have survived. The underlying idea has been termed the sutratman or “thread-spirit” doctrine in which the line symbolizes the life force that animates all living beings and which is

eternal and renascent.1 Like Proteus, the shape-shifter, the line can assume any form until, in the end, it returns to its source. Birth, death, rebirth and the continuity of the social order were all illustrated using the continuous line.

Primitive and Modern Art

Most of the examples in this paper are taken from ancient and tribal cultures but it will help to begin with more modern examples since they illustrate an important element of the continuous-line drawing— motion.

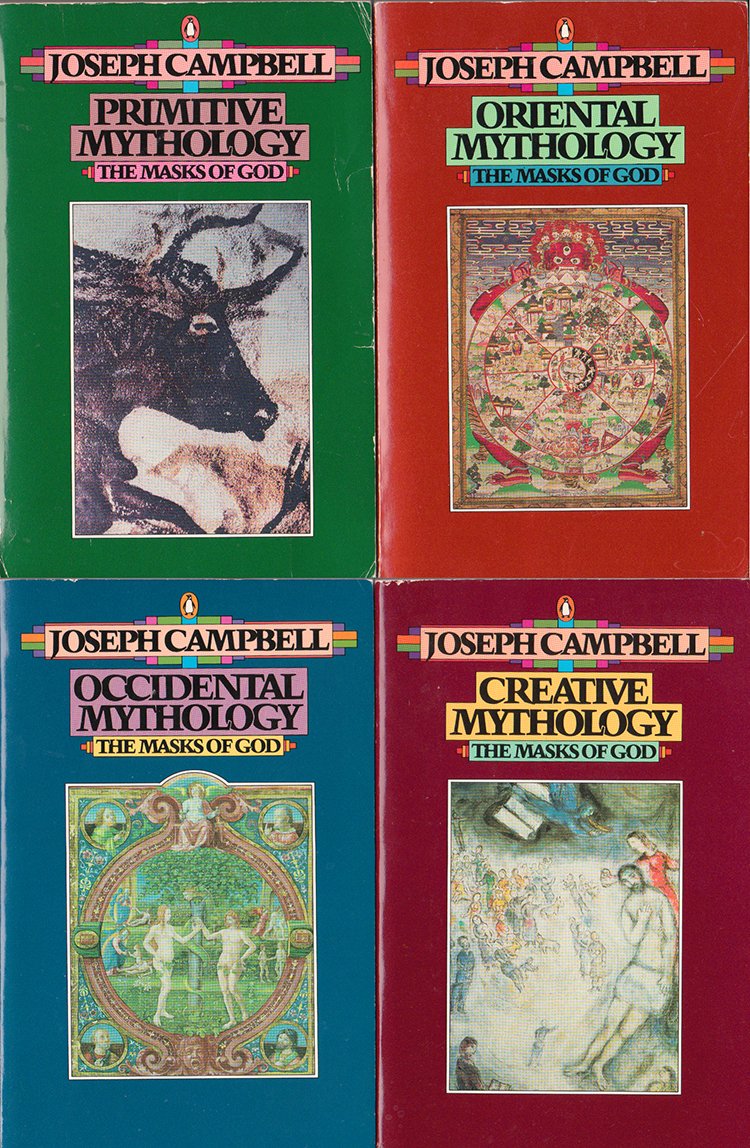

Figure 1: Pablo Picasso, drawing of a horse

In the early part of the 20th century, European artists like Miro, Klee and Picasso rediscovered the continuous-line and used it in their works. It was part of a growing interest in primitive art which reflected itself in different ways. The Cubists were interested in African art, for example, while the Surrealists favored Northwest Coast American Indian art and the arts of the Pacific. Specific forms were borrowed and reused, albeit in far different contexts than the originals. In 1984, the Museum of Modern Art mounted a show on the subject which received a lot of media attention. The juxtaposition of the primitive and modern was instructive but the commentary that followed was not; an avalanche of moralism and political rhetoric that precluded any deeper discussion of the underlying connections that first generated the interest of modern artists in these ancient forms. It was clear that none of the artists were scholars and had little background in primitive art. It was also clear that many of them were superb collectors with an eye for genuine pieces. They may not have understood the meaning of the art they were copying, but they did understand something about the construction of these works and the sensory preferences that lay behind them.

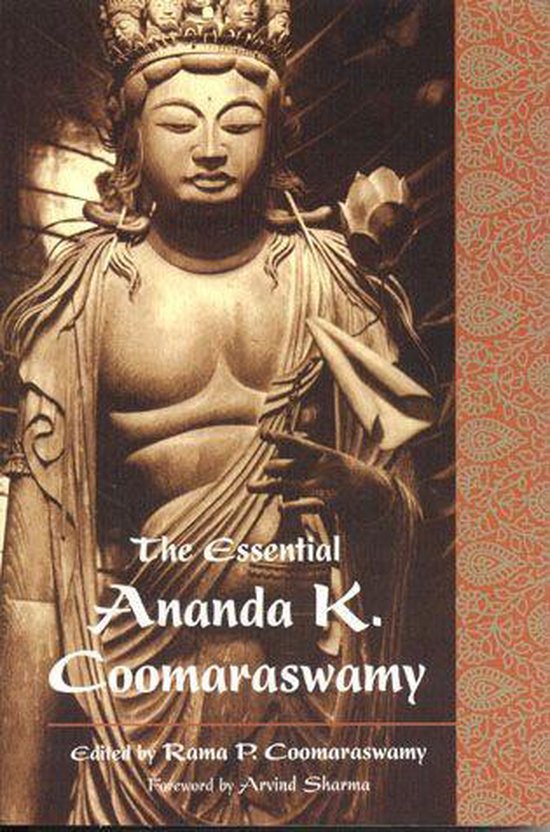

Figure 2: Paul Klee, Irony at Work

A generation earlier, the Bohemian-born Swiss art historian, Siegfried Giedion (1888-1968), did have some thoughts on the subject, which he published in 1948 in Mechanization Takes Command. It was not the most likely place for such a discussion, a few pages within a long book about the mechanization of American life. But Giedion was not your average art historian.

In a section titled “Scientific Management and Contemporary Art” he took up the issue of the redesign of work processes in America, pioneered by Frederick Taylor (1856-1915) and continued and expanded by Frank Gilbreth (1868-1924) and his wife, Lillian Moller Gilbreth (1878-1972).

The goal of Scientific Management was to analyze the work process to reduce the time it took to accomplish a task and to make the work less stressful. This was done by studying the physical motions of the worker through space and time. Gilbreth tried using a motion-picture camera to analyze movement but it did not make the trajectory of the motion clear enough because it portrayed it only in relation to the entire body.

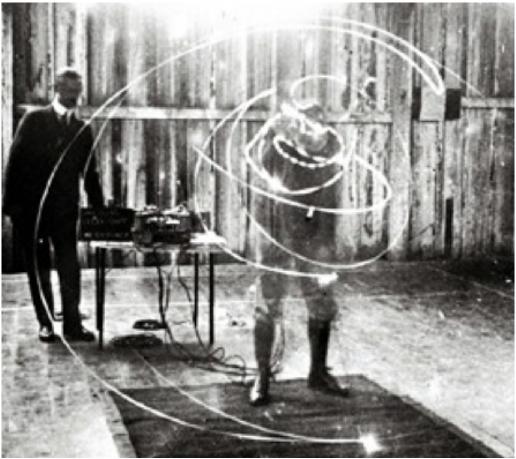

To accomplish the separation, Gilbreth invented a device of appealing simplicity. An ordinary camera and a simple electric bulb were all he needed to make visible the absolute path of a movement. He fastened a small electric light to the limb that performed the work, so that the movement left its track on the plate as a luminous white curve. This apparatus he called a ‘motion recorder’—Cyclograph.

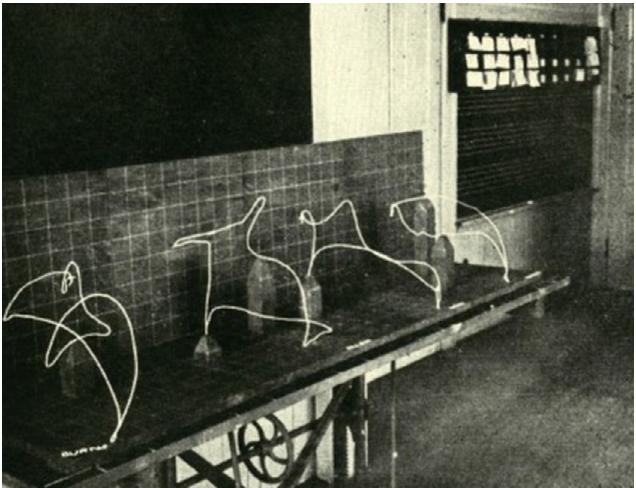

Figure 3: Motion of a golfer’s swing using a Cyclograph Later, Gilbreth made wire models of these recordings.

These wire curves, their windings, their sinuosities, show exactly how the action was carried out. They show where the hand faltered and where it performed its task without hesitation. Thus the workman can be taught which of his gestures was right and which was wrong.

Giedion was astute enough to realize that problems involving the representation of motion were of particular interest in the first half of the twentieth century to engineers, scientists, and artists alike. The development of the motion picture camera, the automobile and the airplane had registered their affects on the human psyche which had to be worked out separately in these various disciplines. Gilbreth’s wire models closely resemble continuous-line drawings. Their common element is the depiction of motion, traced with a continuous line, a beam of light, or twisted wire in this case.

Figure 4: Wire models of Cyclotron images

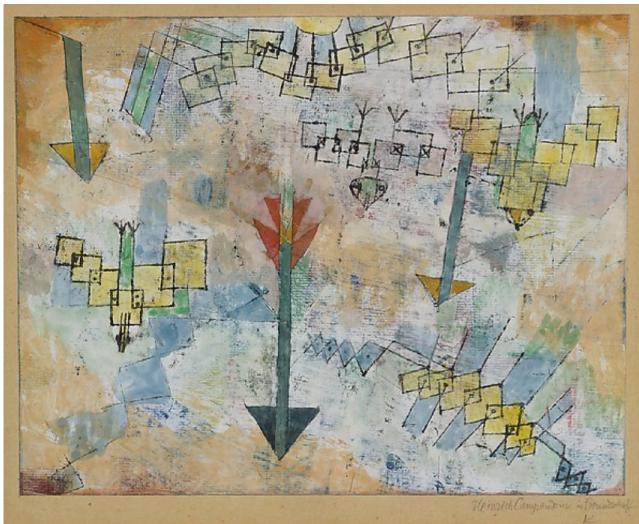

Paul Klee was particularly eloquent in his writing and teaching about the role of motion in art. Perspective was no longer enough, the dynamism of process must be conveyed and the continuous line was one way to do this. He experimented with color and with the direction-pointing arrow, soon to be adopted internationally as a symbol of motion and direction.

Figure 5: Paul Klee, Birds Swooping Down and Arrows, Metropolitan Museum of Art

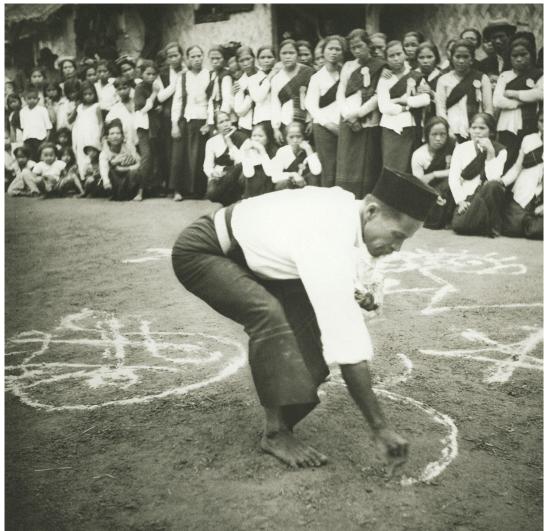

It is motion that links the modern use of this form with ancient examples which were drawn on the ground or laid out in sand or colored powder, often to the accompaniment of music.

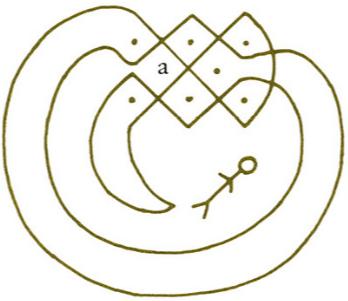

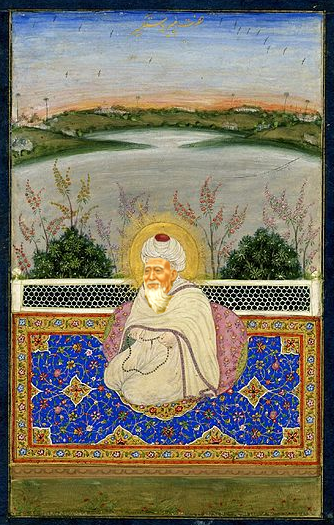

Figure 6: Batak sorcerer (datu), Sumatra

It will be our purpose here, to determine as far as it is possible, what the intentions of these early artists were. We will find that they looked to the past rather than the present for their subject matter and inspiration. They were upholders of tradition and in this way, differed radically from modern artists whom Ezra Pound termed, “the antennae of the race.”

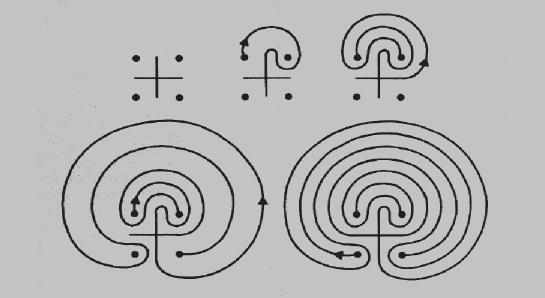

Methods of Construction

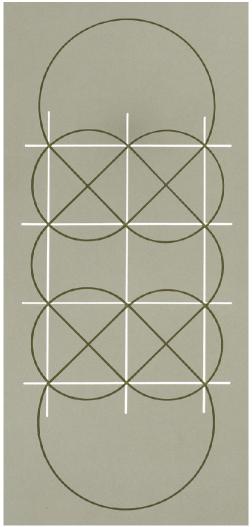

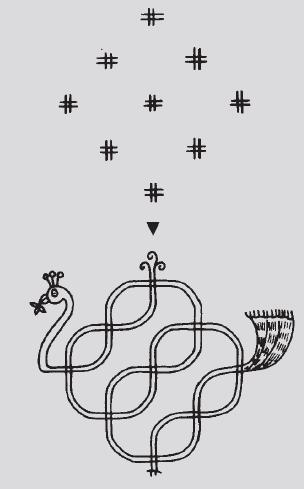

The American art historian, Carl Schuster (1904-1969), collected continuous-line drawings from many cultures and time periods. To construct such a drawing, an artist usually began with a framework of dots and drew an unbroken line through or around them to form a figure or pattern. The essential element is the unbroken nature of the line and the smooth completion of the image.

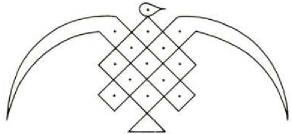

Figure 7: Sand drawing of a bird, Quioco, Angola

The guiding dots serve both a symbolic and a practical function. They aid the beginner in constructing the work. Experienced artists often dispense with the guides once they have learned to draw the image smoothly, without hesitation. It will become clear as we progress, that the dots were originally meant to represent joint marks, connected to reanimate the figure. A kind of connect-the-dots exercise with deep spiritual significance which gradually lost its meaning over time, eventually devolving to child’s play.

Figure 8: Head of elephant, Quioco, Angola

Examples

We find numerous examples of continuous-line drawings in Africa among the Bantu-speaking tribes of Angola, Zaire, and Zambia. Paulus Gerdes has documented these drawings, called sona by the Tchokwe, and analyzed the tradition as a whole, both in Africa and elsewhere.

Figure 9: Maze with human figure, Quioco, Angola

Edmund Carpenter remarks, “at least one of these designs [Figure 9] is a maze with a human figure in it. The Quico identify the figure as the body of a slave found in the grass. They say the design of this maze will reveal the real identity of the killer.”2 The connection between continuous-line drawings and mazes or labyrinths is a matter of some interest and relates to some of the oldest ideas associated with the form centering around death and rebirth.

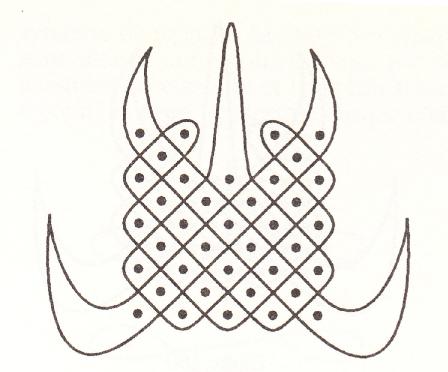

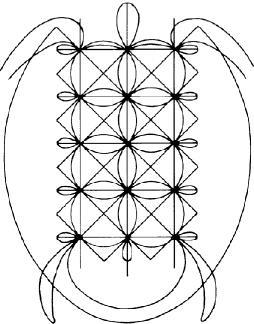

Another remarkable set of continuous-line drawings was collected in the early part of the 20th century from the New Hebrides, a Melanesian archipelago, by the anthropologists John Layard, Bernard Deacon, and Raymond Firth. A missionary, Ms. M. Hardacre, added several more examples. The drawings were both religious and secular and depicted a variety of subjects including birds, animals, fish, and plants (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Malekulan sand drawing of a turtle

They were generally drawn for amusement and in some cases, stories were related as the figures were drawn. On the Island of Raga, two sides took turns drawing, each trying to outdo the other.

...knowledge of the art is entirely limited to men; women, of course, may see the designs. The whole point of the art is to execute the designs perfectly, smoothly, and continuously; to halt in the middle is regarded as an imperfection.

The techniques used to draw these complex figures are handed down from generation to generation and each design is practiced assiduously to ensure mastery. Once learned, the skill remains in the body of the practitioner, like dancing or jumping rope.

The methods of construction used in the New Hebrides are common to the tradition wherever it is found. First a patch of sand or earth is made level and smooth, or an area with volcanic dust may be used. Sometimes ashes are spread on the earth to provide a clean drawing surface. Next, the artist draws a framework consisting of lines set at right angles and crossing one another, or a series of small circles arranged in a regular pattern. This preliminary layout serves as a guide for constructing the drawing. The artist then smoothly traces the curves, circles, and ellipses around or through the guides until the figure is completed.

In theory, the whole should be done in a single, continuous line which ends where it began; the finger should never be lifted from the ground, nor should any part of the line be traversed twice. In a very great many of the drawings, this is actually achieved.

In some drawings lines must be retraced to avoid lifting the finger. In others, small details are added to complete the drawing, like a tail feather or eyes. More complex designs may involve several interconnected line drawings. Of particular interest are those New Hebridean designs that are the property of the secret societies and relate to initiation and the mysteries of life after death. In Vanuatu on Malekula, the second largest island in the group, and elsewhere in the New Hebrides, the home of the dead is reached by an arduous journey.

Figure 11: Drawing of Nahal (The Path), New Hebrides

Ghosts of the dead…pass along a ‘road’ to Wies, the land of the dead. At a certain point on their way, they come to a rock…lying in the sea…but formerly it stood upright. The land of the dead is situated vaguely in the wooded open ground behind the rock and is surrounded by a high fence. Always sitting by the rock is a female [guardian] ghost [called] Temes Savsap, and on the ground in front of her is drawn the completed geometrical figure known as Nahal [Figure 11], ‘The Path’. The path which the ghost must traverse lies between the two halves of this figure. As each ghost comes along the road the guardian ghost hurriedly rubs out half the figure. The ghost now comes up but loses his track and cannot find it. He wanders about searching for a way to get past the guardian ghost of the rock, but in vain. Only a knowledge of the completed geometric figure can release him from the impasse. If he knows this figure, he at once completes the half which Temes Savsap rubbed out; and passes down the track through the middle of the figure. If, however, he does not know the figure, the guardian ghost, seeing he will never find the road, eats him, and he never reaches the abode of the dead.

Among the northern peoples of the New Hebrides, the Lambumbu, Legalag, and Laravat, similar ideas prevail only here the land of the dead is called Iambi or Hambi and the geometrical figure, ‘The Stone of Iambi’ (Figure 12). Further, no test is required of the traveling soul. Variants of the story are told in Mewn and among the Big Nambas tribe, where the ghost is known as Lisevsep.

Figure 12: Stone of Iambi, New Hebrides

Initiates in the secret ghost societies such as those on Ambrim are taught these designs so they may enter the Afterworld when they die. They are also part of a larger cycle of rites.

A key dance in the Malekulan cycle of ceremonies represents, simultaneously, a sacred marriage, an initiation rite and, most important of all, the Journey of the Dead. At one point, participants enact a swimming movement to represent the crossing of the channel to the land of the dead. In the final movement, Maki-men form in two rows: then members of the introducing ‘line’, already fully initiated, thread their way between these ranks. This progression of initiates corresponds with the path followed by the dead man through the maze-like design Nahal.

Figure 13: Woman drawing threshold designs, South India

Continuous-line drawings are also common in the southeastern part of India where they still drawn today (Figure 13). The Tamils refer to such drawings as kolams and they are drawn in front of dwellings, normally before sunrise. The woman of the house will smear a bit of ground with cow dung or sweep the threshold and sprinkle it with water to prepare her canvas. In the past, rice powder was run between the fingers to form the design. Quartz powder is used today. Dots or crossed lines are used as a framework and the kolam is formed from a single, uninterrupted line. Traditional designs are strictly geometrical though more naturalistic forms have developed in modern times. Similar designs are also found as tattoos and on mortuary pottery.

Figure 14: Rangoli design of a bird, India

In Northern India, figures called rangoli or rangavalli are drawn in courtyards, on the walls of buildings, and at places of worship. Rangoli designs tend to be more elaborate than kolams and are often multicolored. Elaborate floral or animal designs are drawn using the fingers or brushes. Many of the older designs are geometric, however, and bear the telltale dots and guide lines. Figure 14, a bird, is constructed from a framework of nine crosses. Additional features like tail decorations were added afterwards.

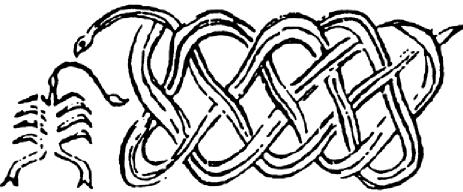

Figure 15: Snake and scorpion, Mesopotamia

The technique was also known in ancient Mesopotamia as evidenced by a number of serpent designs engraved on argillite cylinder seals from the 3rd millennium (Figure 15). While the serpent is not constructed from a continuous line, its shape indicates that the artist was familiar with the dot-and-line method common to the tradition.

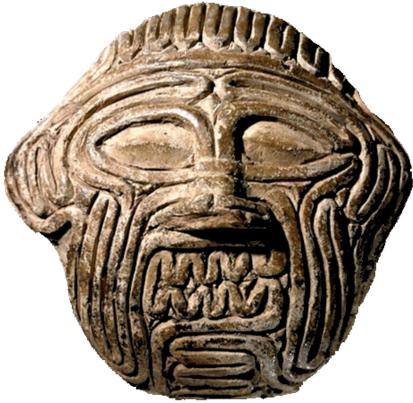

Another interesting example from ancient Babylonia is made of clay and appears to be constructed from a single coil. The face is identified as Humbaba, a demon of the underworld who is slain by the epic hero, Gilgamesh.

Figure 16: Clay figure of Humbaba, Babylonia (c. 1800-1600 B.C.)

The maze-like lines of the face part of the common equation of the underworld with the intestines, human or animal. This complex of ideas is very old if we can judge by its distribution and appearance in both the Old and New Worlds. We will return to this idea when we discuss the relationship of the continuous line to mazes and labyrinths.

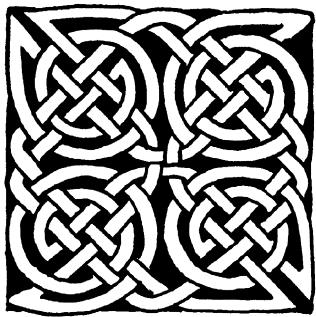

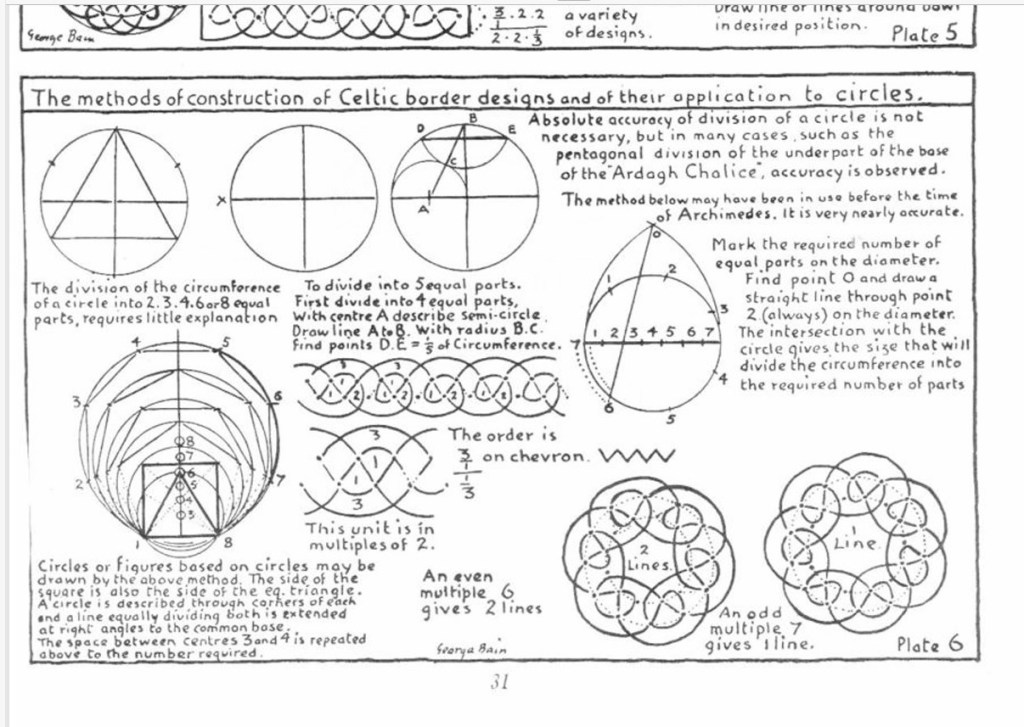

Figure 17: Celtic knotwork design

Perhaps the most familiar continuous-line drawings are the knotwork designs of Celtic art (Figure 17) that were used to decorate metalwork, stone monuments, and manuscripts like the famous Book of Kells. George Bain, who unraveled the methods used in constructing these complex designs, found their astonishing complexity to be based on a few simple geometrical principles.

Bain’s research highlighted the connections between Celtic art and its religious, legal, and philosophical contexts. He noted that the use of knots and interlace motifs was often influenced by religious prohibitions on figurative representation, which led to ingenious decorative strategies in manuscripts and sculpture. His work also traced design influences between ancient Mediterranean, Asian, and North-European cultures, helping to clarify the origins and meaning of Celtic visual motifs.

- Celtic knotwork often symbolizes eternity, the interconnectedness of life, or unbroken spiritual paths, as the lines have no beginning or end.

- Spirals can represent cosmic forces, spiritual development, or cycles of birth and rebirth, especially in Insular and Pictish traditions.

- Zoomorphic elements—where knots morph into animal forms—may evoke mythic creatures, protective spirits, or ancestral lineage, blending art with storytelling.

Referring to a page of the “Book of Armagh,” Professor J. O. Westwood wrote, “In a space of about a quarter of an inch superficial, I counted with a magnifying glass no less than one hundred and fifty-eight interlacements of a slender ribbon pattern formed of white lines edged with black ones upon a black ground. No wonder that tradition should allege that these unerring lines should have been traced by angels.” One of the aims of this book is to show that there is nothing marvellous in a design having not a single irregular interlacement. Indeed, a wrong interlacement would be an impossibility to a designer conversant with the methods. One might as well marvel at a piece of knitting that had not a mistake in its looping.

Figure 18: Threshold tracing, Isle of Lewis, Scotland

The continuous line also survived in Scotland, where M. M. Banks documented it in 1935. In some rural areas, housewives traced such patterns in pipe clay on thresholds, the floors of houses, and in dairies and byres. The designs, not all of which were continuous-line drawings, were refreshed each morning and were thought to keep away ghosts or evil spirits. One elderly woman in Galloway said that her grandmother had explained the tradition with a couplet:

Tangled threid and rowan seed

Gar the witches lose (or lowse) their speed

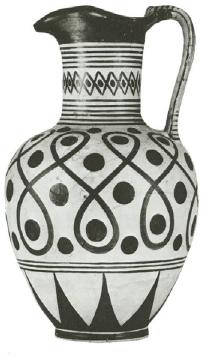

The example in Figure 18 is missing the guiding dots but a Greek vase from the 8th century B.C. with a similar design is not (Figure 19). The extra dots indicate the artist was imitating a design that was no longer understood. The Greeks viewed barbarian art much in the manner of modern decorators and borrowed and adapted freely.

Figure 19: Proto-Corinthian Greek vase, 8th century B.C.

A related motif dating from at least Bronze Age times is the spiral ornament, found in Greece, Rome, Etruria and among Germanic and Celtic peoples. Spiral fibula were used to close garments while a variety of metalwork designs served as arm bands, diadems and the like (Figure 20). Drawn from a single piece of wire, the spiral forms a continuous path ending where it begins, a trait common to the other art forms we have been discussing.

Figure 20: Bronze spiral arm band, 1600 B.C., Migration Period, Europe

The art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy comments on the symbolism of the spiral fibula.

The primary sense of “broach” (= brooch) is that of anything acute, such as a pin, awl or spear, that penetrates a material; the same implement, bent upon itself, fastens or sews things together, as if it were in fact a thread. French fibule, as a surgical term, is in fact suture. It is only when we substitute a soft thread for the stiff wire that a way must be made for it by a needle; and then the thread remaining in the material is the trace, evidence and “clew” to the passage of the needle; just as our own short life is the trace of the unbroken Life whence it originates.

Drawn from a single piece of wire, the spiral fibula forms a continuous path ending where it begins.

The use of a single line to construct a work of art has a long history as we have seen and examples can be found in a wide variety of media.

It is of little importance, in the different forms that the symbolism takes, whether it be a thread in the literal sense, a cord, a chain, or a drawn line such as those already mentioned, or a path made by architectural means as in the case of the labyrinth, a path along which the being has to go from one end to the other in order to reach his goal. What is essential in every case is that the line should be unbroken.

- Symbolism shapes religious rituals, social identity, and even national icons, allowing communities to share complex ideas through shared visual language.

- The study of symbolism reveals how societies articulate meaning, bridge material and spiritual worlds, and encode important knowledge through art and tradition.

- George Bain, known as the father of the Celtic art revival, reached out and maintained contact with Ananda Coomaraswamy in the 1940s. Coomaraswamy, an esteemed art historian and philosopher specializing in Indian and Oriental art, was one of the most respected scholarly figures of that time and had a strong interest in Celtic culture throughout his career.

- Coomaraswamy admired Bain’s work, and Bain expressed mourning for Coomaraswamy’s passing in the preface to his major book “Celtic Art: The Methods of Construction,” showing a connection that underlined a Celtic-Indian cultural linkage. Their intellectual exchange is regarded as part of a broader cross-cultural dialogue that linked Eastern art traditions and philosophies with Western Celtic revival movement. Core Philosophical Themes in Celtic Tradition

- Interconnectedness and Eternity: Celtic art, especially knotwork, symbolizes the endless, interconnected nature of existence. The continuous loops without beginning or end reflect eternal life, unity, and the infinite cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

- Cycles of Life and Renewal: Many motifs, such as spirals and the triskele (triple spiral), evoke life cycles, cosmic rhythms, and transformation. These represent the soul’s journey through phases of growth, death, and spiritual renewal, aligning human life with natural and cosmic forces.

- Nature and Spiritual Vitality: Celts believed all elements of nature—rivers, rocks, animals, the sun, and the moon—possess spirit and power. This animistic belief is expressed in symbols that honor natural forces and the sacred balance between earth and the cosmos.

- Balance and Harmony: The Awen symbol, consisting of three rays, represents spiritual inspiration as well as the balance between opposites such as male/female energies, mind/body, and opposing cosmic forces.

- Trinity and Triplicity: Triangular and threefold symbols such as the triquetra emphasize important trinities in Celtic belief: life-death-rebirth, body-mind-spirit, or past-present-future. These forms unify spiritual, natural, and philosophical concepts in a single visual.

- Philosophical Role of Celtic Symbols

- Symbols were used as tools in rituals, healing, and oral traditions to convey wisdom and cosmic truths.

- They acted as spiritual maps for meditation and guides for eternal truths embedded in everyday life.

- Their meanings often combine Christian symbolism with pre-Christian pagan beliefs, showing cultural continuity and transformation.

- In essence, Celtic traditions and philosophies express a profound spirituality centered on eternal cycles, unity with nature, and the balance of cosmic and human forces, richly encoded in their symbolic art and motifs

- these motifs and symbolism is still to be seen in Frisian Crafmanship:

For the Frisian Eternal Knot see The wisdom of Frisian Craftmanship

Ananda Coomaraswamy viewed the motif of two birds, especially twin or entwined birds, as deeply symbolic rather than merely decorative. He connected this symbolism across cultures, noting similarities between Celtic traditions and Indian texts like the Upanishads.

In these traditions, two birds often represent dualities or pairs of opposites—such as soul and body, divine and human, or inner and outer realities—reflecting a metaphysical unity through their relationship. Coomaraswamy saw twin birds as carriers of spiritual meaning, like “psychopomps” (soul guides) or symbols of the soul’s journey and transcendence.

This symbol appears in Celtic art as interlaced bird motifs serving not just as ornament but as a representation of life’s dual nature and spiritual truths, paralleling similar uses in ancient Indian cosmology and philosophy. Coomaraswamy’s comparative approach highlighted how such motifs are expressions of common archetypes across cultures, embodying spiritual and philosophical ideas through natural imagery.

Ananda Coomaraswamy interpreted the motif of twin birds in myth as a profound symbol of spiritual unity and duality. In a letter to George Bain in 1947, he explained that the two birds often found in traditional design represent the friendship or unity between the “inner and outer man,” meaning the spirit and body within every person. This is also reflected in the Indian Upanishads, where two birds perched on the same tree symbolize the universal self and the individual self—the true self and the ego.

Coomaraswamy elaborated that this symbolism captures the resolution of internal conflict and self-integration, the core goal of true psychology and spiritual development. He quoted the Upanishadic passage: “Two birds, fast bound companions, clasp close the selfsame tree, the tree of life,” indicating the inseparable, complementary nature of these dual aspects.

Thus, the twin birds in Celtic art, far from mere decoration, encapsulate themes of unity, friendship, and the relationship between body and spirit—an archetype that crosses cultural boundaries between Celtic and Indian traditions alike.

The blue tit symbolizes joy, cheerfulness, hope, and positive transformation, along with deeper meanings of love, loyalty, adaptability, and spiritual renewal in various folkloric and spiritual traditions.

Joy and Positivity: The blue tit’s vibrant colors and playful behavior represent happiness,

cheerfulness, and a reminder to embrace joy and positivity even in difficult times.

Love and Loyalty: Folklore often associates blue tits with love, trust, and enduring faithfulness —these birds are monogamous and known for lifelong pair bonding, making them symbols of committed partnership and loyalty.

Hope and Renewal: Encounters with blue tits are viewed as omens of hope, new beginnings, and brighter futures after adversity.

Adaptability and Resourcefulness: Blue tits are known for their intelligence and ability to

thrive in changing environments, symbolizing resilience and making the most of available

resources.

Communication and Self-Expression: The species is vocal and expressive, offering a metaphor for clear communication and encouragement to openly share feelings and truths.

Spiritual Meaning: The blue coloration is often tied to spiritual awakening, divine intelligence,

and healing, while the bird itself might be interpreted as a messenger of spiritual guidance

and connection.

Cultural and Mythic Contexts: In Celtic and European folklore, blue tits represent good luck, honor, and protection—sometimes regarded as carriers of souls or spirits.

In sum, the blue tit in Dutch symbolism embodies themes of love, hope, joy, and spiritual

guidance, carrying a gentle but enduring message of faithfulness and renewal within the

broader tapestry of Dutch folklore and natural tradition.

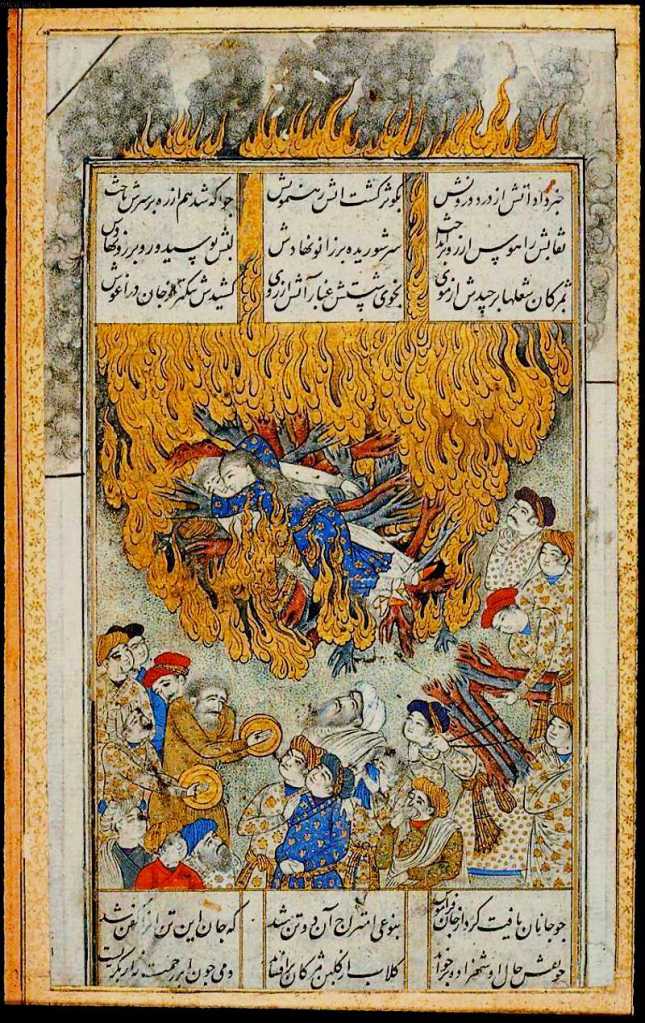

- Simorgh

However, historically and mythologically, the Simorgh (or Simurgh) is a legendary Persian bird often associated with divinity, wisdom, and mythical power in Persian literature and Sufism. It is a large, benevolent, mythical bird said to possess great knowledge and spiritual

significance, sometimes seen as a symbol of the unity of all beings or divine intervention.

The Avesta (Zoroastrian holy scripture), specifically the Bahman Yasht and Rashnu Yasht,

where Simurgh is mentioned as Saêna, a divine bird associated with healing, fertility, and

divine blessing, roosting on the cosmic Tree of Life that contains all medicinal plants.

Minooye Kherad (a Zoroastrian wisdom text from the late Sassanid era), which elaborates on Simurgh’s role in healing and seeds of all plants.

The Shahnameh (The Book of Kings) by Ferdowsi, a seminal Persian epic poem from around 1000 years ago, that narrates the Simurgh raising the hero Zal, assisting in the birth of Rostam through surgical knowledge, and healing wounds with magical feathers.

“The Conference of the Birds” by Farid ud-Din Attar, a 12th-century Sufi mystical poem,

where the narrative centers on thirty birds searching for the Simurgh, eventually realizing

they themselves embody the Simurgh, symbolizing divine unity and spiritual awakening.

These texts collectively form the core of the spiritual and mystical traditions relating to the

Simurgh as a divine, healing, wise, and unifying figure in Persian and Sufi cosmologies.

The phrase “Simurgh is 30 birds” comes from the famous 12th-century Sufi poem “The

Conference of the Birds” by Farid ud-Din Attar. In this allegorical tale, a gathering of birds

embarks on a spiritual quest to find their king, the Simurgh. The journey involves crossing

seven valleys symbolizing the stages of spiritual growth.

Out of the many birds on this journey, only thirty complete it and reach the Valley of Simurgh.

When they finally meet the Simurgh, they are astonished to discover that the Simurgh itself is none other than their collective selves. The name “Simurgh” is a pun in Persian: “si” means thirty and “morgh” means birds, hence “thirty birds.” This revelation symbolizes the spiritual realization that the divine they sought is actually the true nature of themselves, emphasizing unity and self-realization.

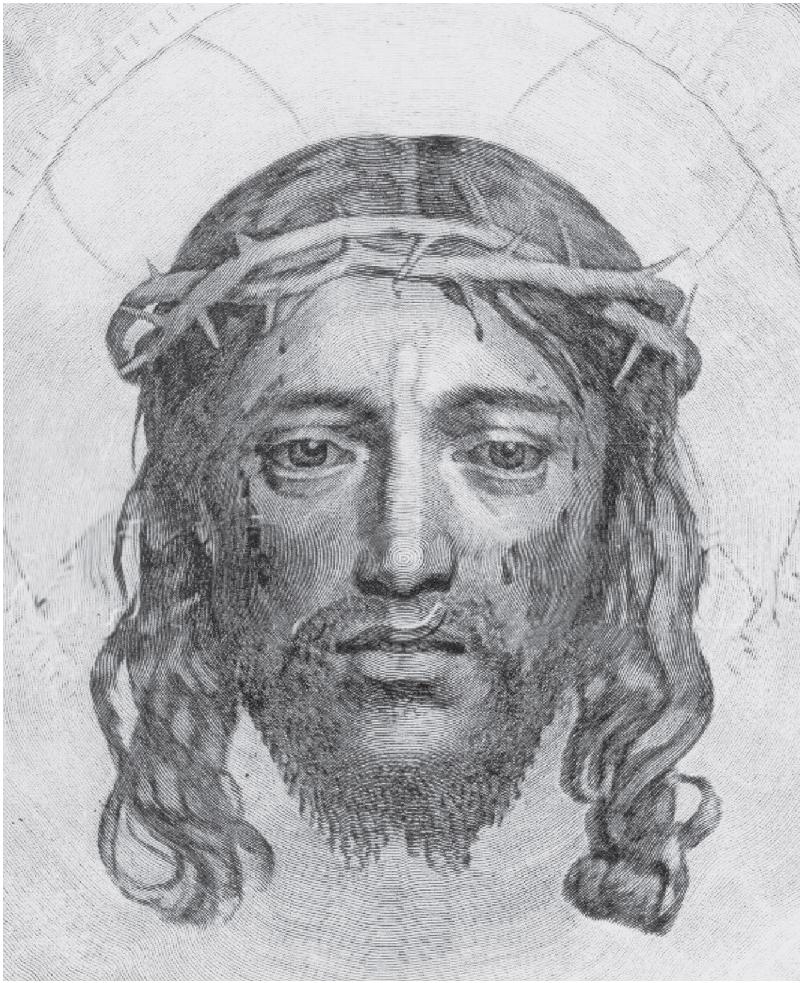

That the meaning of this symbolism was still understood in later periods can be seen in the work of Claude Mellan (fl. 1598–1688), whose remarkable engraving of Christ is composed from a single spiraling line (Figure 21). The Latin words underneath, Formatur unicus una (“By one the One is formed”), refer both to Christ and to the technique used to construct the work.

Figure 21: Claude Mellan engraving, The Face of Christ on the Sudarium.

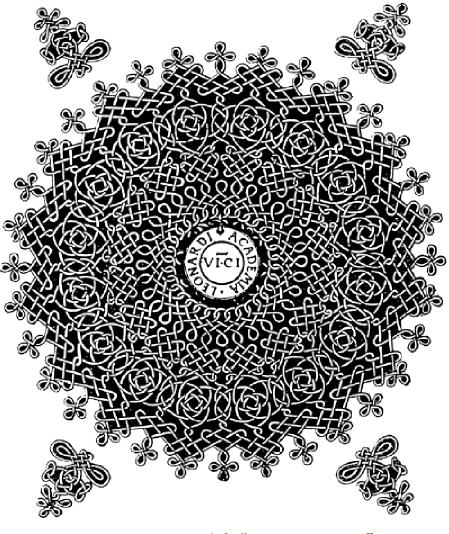

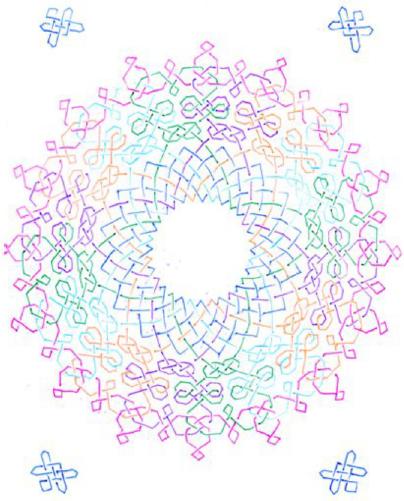

Dr. Coomaraswamy took up a related motif in “The Iconography of Durer’s ‘Knots’ and Leonardo’s ‘Concatenation’” where he discussed the symbolic meaning of certain knotwork designs found in the engravings of Albrecht Dürer and the works of Leonardo da Vinci.

Figure 22: One of Albrecht Dürer’s “Sechs Noten”

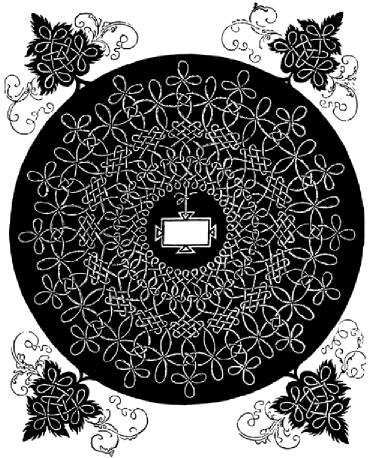

Figure 22 is a wood engraving of Albrecht Dürer’s taken from a series, Sechs Knoten. In each of the six engravings, the central design is constructed from what appears to be a single white line on a black ground. There are actually six intersecting continuous-lines in the central ornament but it is hard to tell without tracing each line. Four smaller knot designs, all of them identical, occupy the corners. In each case, one or more continuous lines form an extremely complex series of designs that resemble lace work or embroidery patterns. The function of this artistic tour de force is uncertain, but the designs may be patterns intended for use in other media.

Figure 23: Leonardo Da Vinci’s Concatenation

In the opinion of many scholars, Dürer’s knot designs are variations on a copper engraving attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci that bears the words, “Academia Leonardi Vinci” within the central medallion (Figure 23).

Leonardo de Vinci, Albrecht Durer and Michelangelo were engaged in a renaissance of the Byzantine forms of Celtic knotwork. Vasari says that “Leonardo spent much time in making a regular design of a series of knots so that the cord may be traced from one end to the other, the whole filling a round space.” The example of his work shown herein [Figure 23] cannot be the one that Vasari had traced its line from end to end, for it has a number of lines. The student can find how many. The designs by these most famous artists were engraved and printed for the use of painters, goldsmiths, weavers, damaskeeners and needleworkers.1

Jessica Hoy and Kenneth C. Millett performed a mathematical analysis of Leonardo’s Concatenations and the Dürer copies and found that they were all composed of multiple continuous lines, or “links” as they are classified in mathematics. Figure 24 highlights the components.

Figure 24: Components parts of Durer’s first knot engraving (after Hoy & Millett)

The technique of combining continuous lines is found throughout the tradition as a whole and it adds to the mystery of these constructions since they appear to be composed of a single line. A great deal of variety is possible using this method.

Coomaraswamy noted the similarity between Leonardo’s Concatenation, as it is called, and the cosmic diagram known as a mandala.

The significance of Leonardo’s “decorative puzzle”—which from an Oriental viewpoint must be called a mandala—will only be realized if it is regarded as the plane projection of a construction upon which we are looking down from above.

The dark ground represents the earth, which is associated metaphysically with the substantial, potential aspects of manifestation. The white line is the Spirit, the essential, active aspect of manifestation whose source is the summit or center (Heaven). The four corner ornaments are the cardinal directions and reflect the seasons (time), and the older conception of a quartered universe held together by the Spirit. The whole construction is summarized best in the words of Dante (Paradiso XXIX.31-6) to whom the meaning of these esoteric symbols was familiar.

Co-created was order and inwrought with the substances; and those were the summit in the universe wherein pure act was produced: Pure potentiality held the lowest place; and in the midst potentiality with act strung such a withy as shall never be unwound.1

Did Leonardo understand the symbolic meaning of his own work or was he merely copying an older design?

Leonardo’s Concatenation is a geometrical realization of this “universal form.” He must have known Dante, and could have taken from him the suggestion for this cryptogram. But there is every reason to believe that Leonardo, like so many other Renaissance scholars, was versed in the Neo-Platonic esoteric tradition, and that he may have been an initiate, familiar with the “mysteries” of the crafts. It is much more likely, then, that Dante and Leonardo both are making use of the old and traditional symbolism of weaving and embroidery.2

String Figures

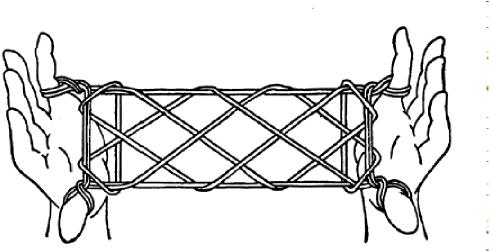

String figures are known on every inhabited continent and show evidence of the greatest antiquity. Americans are most familiar with the game called Cat’s Cradle in which a string is looped in a cradle-like pattern on the fingers of one person’s hands and transferred to the hands of another to form a new pattern. In fact, Cat’s Cradle is but one variant of an art that while simple in principle, is far more complex in practice.

To create a string figure, a loop of string, fiber, hair, sinew, bark, or other pliable material is manipulated to form patterns using the hands, feet, mouth, knees and even teeth (Figure 25). The art is practiced alone or by several people. In the hands of a skilled practitioner, the loop of fiber can be manipulated to create complex figures that transform to illustrate a story or song or to prepare the viewer for a sudden denouement. Completed patterns may represent objects in the natural environment like plants and animals, activities such as hunting or fishing, or geometric patterns such as diamonds or zigzags.

Figure 25: Method of constructing a string figure

There are also tricks in which the completed pattern resolves suddenly into a continuous loop, or “catches,” in which a figure tightens suddenly around the finger of an unsuspecting participant.

Though many practice the art, male and female, young and old, a master of the form must combine the legerdemain of the professional magician with the singing and story-telling art of the bard or shaman. String figures are at once an amusement, a lesson to help the young remember, a means to illustrate stories and myths, and a doorway for initiates into the mysteries of death and rebirth.

Starting with the assumption that the string represents the Spirit, the artist in string is in a position to re-create the world in microcosm. Like Proteus or the other shape-shifters of mythology, the string can be transformed from one figure into another. It is the drama of human existence that is on display. When the game is over, everything returns to the endless loop so the play may begin anew.

String figures are closely related to continuous-line drawings. The loop of string is the three-dimensional equivalent of the continuous line, used to create a pattern in the sand. In some cultures, completed string figures are actually removed from the hands and placed on the ground, emphasizing this connection. Both forms are used for storytelling and both once had deeper meanings centered on death and rebirth.

Among the Cahuilla Indians, the string figure played the same role as the sand drawing did among the Malekulans.

Moon also taught the people to play what we call Cat’s Cradle — a string figure game and a predictive technique necessary to know in order for the soul, it was said, to get into Telmekish, the land of the dead (Hooper 1920: 360). They had to know many figures because as the soul traveled to the land of the dead they had to tell Montakwet, the shaman-person who guarded the entrance to Telmekish, what they meant. If they couldn’t tell him, they would not be admitted. The same game, a favorite recreation for Cahuilla women, could predict the sex of a child.1 A similar story is related concerning the residents of the Gilbert Islands.

Prayers and incantations accompanied the making of string figures in the Gilbert Islands, as in other cultures. In Gilbertese mythology two notables were associated with string figures, Na Ubwebwe and Na Areau the Trickster (Maude & Maude 1958:9). Not only did Na Ubwebwe use sympathetic magic in the assistance of creation, but he also smoothed the way for the dead. At the ceremony known as tabe atu (the lifting of the head) an individual described as the “straightener of the path” performed a series of string figures beside the corpse. The figures included Tangi ni Wenei (The Wailing Over the Dead), (Maude & Maude 1958:25). On the way to the land of the departed ancestors the spirit meets a woman with the beak of a bird, Nei Karamakuna. Unless the spirit has been tattooed, in which case the tattoo marks are pecked out, the eyes will be pecked out instead. Naturally most Gilbertese take the precaution of being tattooed. Soon after meeting Nei Karamakuna the spirit meets Na Ubwebwe who makes a series of string figures with him or her. The spirit must make the series without a mistake until the first figure, called Na Ubwebwe, appears again. Only then can the spirit “pass on.”

The authors conclude that whether the sequence for one player used at the raising of the heavens, or the series performed by two persons during the tabe atu ceremony, “the figure of Na Ubwebwe is made as a rites de passage connected with death.”

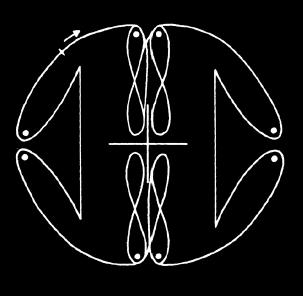

Figure 26: Framework for constructing continuous-line drawings and string figures

String figures also resemble continuous-line drawings in their manner of construction (Figure 26). Instead of guiding dots drawn on the ground, the finger joints (or other body parts) serve as the guides around which the string passes. The essential point is that the guiding dots used to construct continuous-line drawings were once understood as body joints. Joint marks are the link between the various versions of the thread-spirit doctrine. The line is the Spirit connecting the joints and reanimating the being.

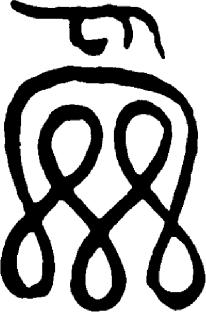

Carl Schuster was particularly interested in a continuous-line drawing that appears in a Shang Dynasty inscription from the 13th century B.C. (Figure 27). According to Carl Henzte, it represents an archaic form of the Chinese character, hsi, “to bind” which comprises two elements: a simplified hand (shown at the top) and a skein of silk thread.2 There is also a two-handed version of the inscription that developed into the Chinese character luan, “to bring into order,” by adding another element that means “speech”. A similar development led to the modern Chinese character, tzu, meaning “concept, speech, expression, written composition.

Figure 27: Shang Dynasty inscription, China

It would seem that the ancient Chinese associated the idea of spoken and written communication with the endlessly looped cord. Henzte explains:

Therefore, something must have been spoken while the skein of silk was brought into order; or else the putting into order of the skein was in itself an action somehow equivalent to a sign-language or the expression of a concept. This reminds us inevitably of the thread-games [string figures’ or Cats’ Cradles], known to us especially from Polynesia…. Indeed, the function of the thread-game is in a sense mnemonic, in so far as the production of each figure was accompanied by the recital of a specific chant or mythological story, which was then acted out. Today the thread-game is unknown in China. But was it unknown in ancient times? … The I-Ching (Book of Changes) mentions a kind of knot writing.1

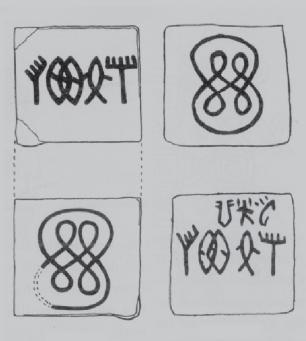

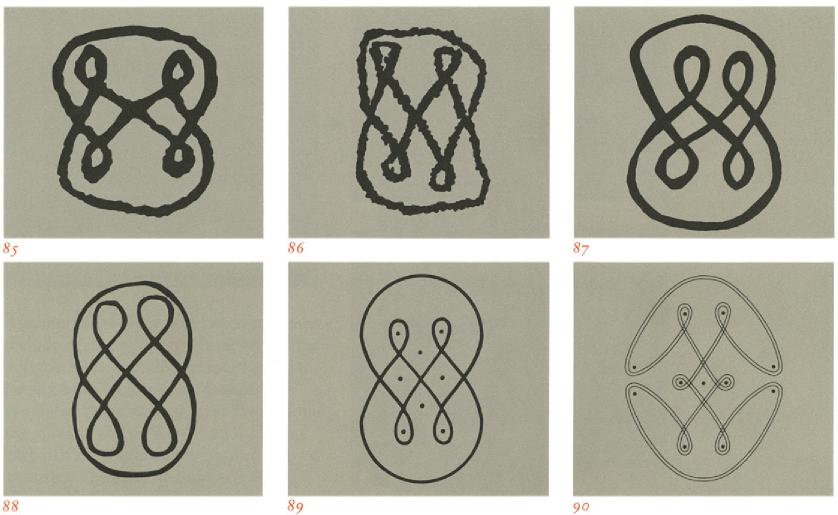

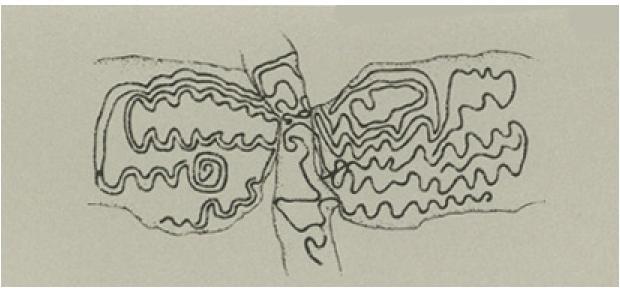

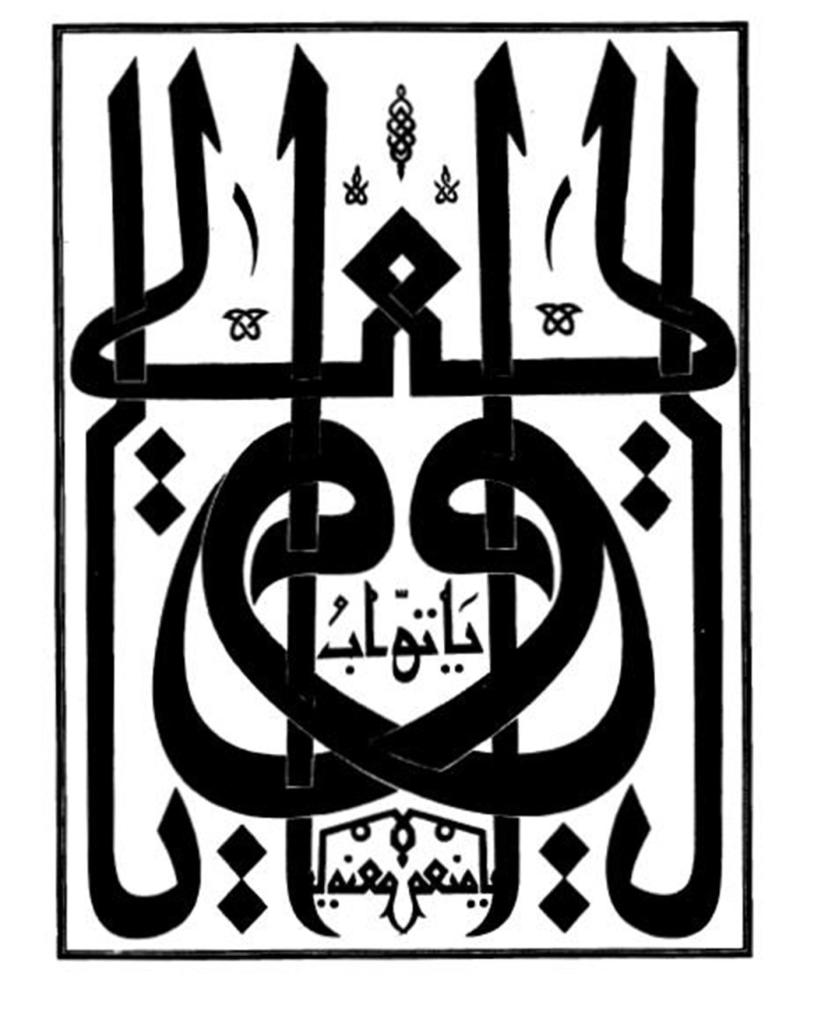

Was the development of writing derived from the use of mnemonic devices like continuous-line drawings and string figures? Schuster found some evidence to support this contention among the Bataks of Indonesia and more significantly in the writing or proto-writing found at Mohenjo-Daro (Figure 28). Are the flanking figures in the other drawings hands?

Figure 28: Copper plates from Mohenjo-Daro, Pakistan This looped design has a wide distribution (Figure 29).2

Figure 29: Looped continuous-line drawings

| Number | Description |

| 85 | Magical design from a Batak manuscript, Sumatra |

| 86 | Design on indigo cloth, Gashaka, Cameroon |

| 87 | Inscribed copper plate, Mohenjo-Daro, Pakistan. 13th century B.C. (?) |

| 88 | Egyptian seal, 1800-1600 B.C. |

| 89 | Ground drawing, Quioco, Angola |

| 90 | Sand tracing, Malekulan, New Hebrides |

Relationship to Mazes and Labyrinths

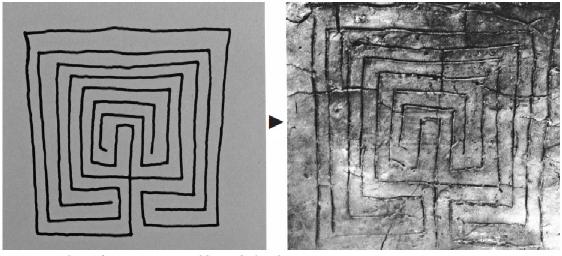

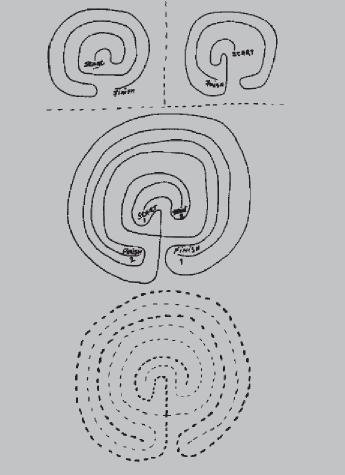

Continuous-line drawings are related to the labyrinth both in the stories and rituals that surround them and in their manner of construction. Before any serious discussion of the labyrinth is possible it is first necessary to distinguish it from a maze. A labyrinth is unicursal; it is impossible to get lost in one since its path, despite its wanderings, leads inexorably to the center (Figure 30).

A maze is full of twists, turns, and dead ends. It is specifically designed to confuse the poor souls caught within it and prevent them from finding their way out. The Labyrinth of Minos was really a maze or Theseus would have had no need of Ariadne’s thread to find his way. The confusion seems to be an old one.

Figure 30: Labyrinth design, India

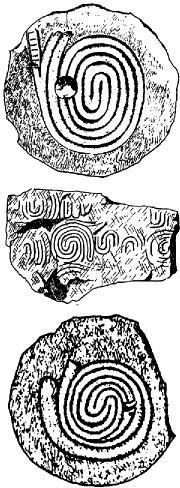

The maze is clearly the older of the two forms. Maze-like patterns have been found on cave walls from prehistoric times (Figure 31). The subterranean world with all its sinuous passages and dead ends is the original model for the maze.

Figure 31: Engraved maze on a tomb lintel, Ireland

The purpose of a maze—in contrast to a labyrinth—was to keep the dead from coming back to bother the living. Claude Lévi-Strauss relates a relevant story in Tristes Tropiques:

As we drew nearer to the trees, we reached the object of our visit—a gravel pit where peasants had recently discovered fragments of pottery. I felt the thick earthenware, which was unmistakably of Tupi origin, because of the white outer coating edged with red and the delicate black tracery, representing, so it is said, a maze intended to confuse the evil spirits looking for the human remains which used to be preserved in these urns.1

In many Meso-American cultures it was thought that the wicked could be mazed in the underworld so their souls would not return. The Aztecs, like the Mayas, believed that while the celestial house— of which their own houses were models—was woven in a straight, orderly, and measured way, the “evil knotted earth” was a twisted and tangled web in which one could become ensnared.

The Chilam Balam of Tizimin refers to the “many roads that lead to death” during the times of injustice, and contrasts the obviously straight and vertical “good roads” by which the dead can ascend quickly to heaven, with the “evil roads” that descend, spreading out on the earth. Ultimately, the latter led to the land of the dead in the thick of the underworld, a place described by Sahagún as having “no outlets and no openings.”

In general, the Meso-American deities or monsters of the underworld were depicted with nets and snares useful for catching evil-doers or other persons unworthy of reaching heaven.

Sometimes, the undulant forms that describe the underworld are aquatic plants; in other instances, the material cannot be identified. What seems to have mattered was not the substance, but its unruly condition. The Popol Vuh describes the jaguars of hell, for example, as “all tangled up”…squeezed together in a rage,” while one Aztec god was named Acolnahuácatl “The One From the Twisted Region,” according to Caso.

The twisted underworld was also associated with the human intestines, an idea that is not as strange as it might seem. If the underworld is conceived as the body of a god, or a god in animal form, and death is a kind of devouring, then the dead must pass through the intestines of this primordial creature. The analogy is also based on the coiled and snake-like appearance of the human intestines and on the purifying role they play within the body. The Aztec goddess of lust and sexual perversity, Tlazolteotl, was called “the eater of ordure.” Those who confessed to her had their sins transformed by her digestive system into fertilizer.3 We are also told that the Aztec underworld was a kind of digestive system located deep within the “bowels of the earth” (an expression we still use) where dwelled monstrous crocodiles not unlike those found in Egyptian or Sumerian mythology.

Figure 32: Babylonian tablets used for divination

Another aspect of the same complex of ideas can be found in the use of animal or human entrails for telling the future. Generally it was the liver and intestines that were used. The Etruscan and Roman haruspices are the best-known examples but the practice was once common worldwide.

The Babylonians divined in this manner and recorded the results on the back of baked clay tablets (Figure 32). A number of these have survived from about 1000 B.C. They depict maze-like patterns on the front; one is inscribed ekal tirani, “palace of the intestines.”1 In ancient Egypt, the dead king was eviscerated and his entrails put into Canopic jars. According to W. Jackson Knight, the bearers of the Canopic jars within the pyramids performed evolutions symbolizing the twisting path of the intestines they were carrying.

If the maze is a sort of flypaper for unclean souls, the labyrinth has the opposite purpose, to reunite the soul with the One, whether conceived as God or a First Ancestor. The labyrinth design itself appears to be of late origin, Bronze Age or a little earlier, but it is clearly an ancestor of the continuous-line drawings and string-figure designs we saw earlier. Those in the know were taught these designs or figures in order to facilitate their passage into the Other World after death.

The origins of the labyrinth are lost to us. It may have begun as an esoteric symbol whose meaning and method of construction were restricted to initiates. If this is the case, it probably existed for millennia before it appeared in a public setting. The earliest dateable labyrinth is from Pylos, Greece (c. 1200 B.C.), a product of the Minoan-Mycenaean culture (Figure 33).3 It was found on the back of a clay tablet the front of which was inscribed with Linear B writing.

Figure 33: Labyrinth on a Linear B tablet, Pylos, Greece

Examples from the Camonica Valley in the Italian Alps may be older than those in Greece but they cannot be dated (Figure 34). Many are really spirals or debased forms, but a number show a human or demonic figure in the center, an important element in the tradition.

Figure 34: Petroglyph, Camonica Valley, Italy

In certain cases a demon is represented in abstract and stylized manner, as a labyrinth whose twistings end at the center of the image in two dots standing for eyes; a third dot sometimes marks the mouth or the nose. These are probably monsters comparable to those of ancient Greece; the legend of the Minotaur doubtless draws its origins from this kind of concept. Sometimes the monster is pictured within the labyrinth; sometimes he seems to be one with it, to be himself the labyrinth. These figures are very common in the rock carvings of Scandinavia, and they constitute one of the principle subjects of the Atlantic megalithic art which stretches from Galicia in Spain to Brittany and Ireland.

Carl Schuster found a suggestive example jabbed on a ladle excavated in Southern Denmark and dated from the early 3rd millennium (Figure 35). Not a true labyrinth, it is close enough to suggest that its creator was familiar with the design but didn’t have the skill to re-create it. This is thoroughly in keeping with the history of the motif.

Figure 35: Ladle with jabbed decoration, Denmark

The procedure is simple—literally child’s play in many parts of the world. Still, relatively few persons, seeing the design drawn according to this scheme for the first time, are able to reproduce it accurately. The blunders which most people make today are precisely the blunders that have been made for thousands of years, in many parts of the world. In fact, this motif has been more often bungled than made correctly—and those blunders are themselves illuminating.

A variety of simplified forms exist, closer to mazes or gapped circles. The most common mistake is the enlargement of the entrance, significant in itself, for many labyrinths were constructed to be entered.

The labyrinth motif is widely distributed and is found in Europe, India, Southeast Asia, parts of Oceania (often in a debased form), North America, Mexico, and perhaps South America—though definitive proof is lacking. Labyrinths constructed of rocks or boulders were once common, particularly in Scandinavia. Many are large enough to enter and were probably used for rituals or games in which the participants walked or danced along the path between the boulders.

Examples from North America, such as those found among the Yaqui Indians of Sonora, Mexico, and the Pima of Arizona differ in no significant way from European examples (Figure 36). Some are incised on rocks while other larger examples are constructed of rocks or boulders. In more recent times, the Pima, Hopi, and Papago used the design on trays and baskets. We don’t know how old the motif is in North America because rock carvings cannot be dated but Carl Schuster believed that the design was part of the cultural heritage of these peoples and not learned from Europeans.

Figure 36: Sandstone carving of labyrinth, Arizona

The labyrinth, like the maze, is associated with the underworld and the afterlife. In many traditions, it is the home of some kind of monster or primordial ancestor who acts as a gatekeeper, restricting access to the Other World.

People who make the labyrinth often describe it as the refuge of some legendary rogue. The Finns have such a story. So do the Pima of Arizona. In India, the labyrinth is known as the domain of the demon Ravana, while the Bataks of Sumatra explain their version of this design as the refuge of the trickster Djonaha. In the Caucasus, the labyrinth is known as the dwelling of Syrdon, a nart or legendary ancestral hero. And in Crete, it served as the lair of the Minotaur, that monster—half-bull, half- human—who was given an annual tribute of seven youths and seven maidens.

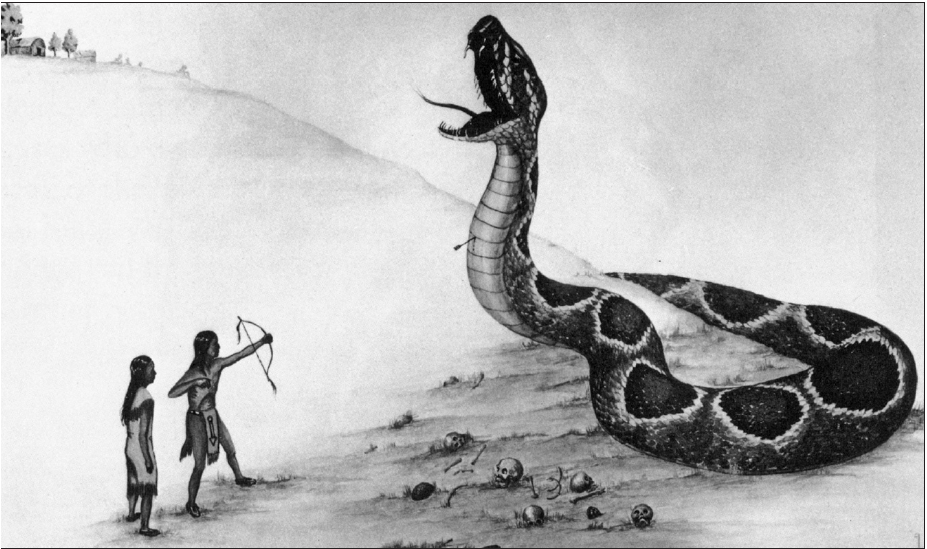

As we have seen, what is clear from the idea of a tangled and intestine-like underworld is that the monster does not so much live inside the labyrinth, as it is the labyrinth (Figure 37). That is to say, passage through its body is required to effect rebirth. A few examples will suffice.

Figure 37: Design on a woven grass mat, Sri Lanka

The Seneca Indians described Kaistoanea, a two-headed serpent (shown here with one head) and denizen of the underworld who devoured the inhabitants of a hilltop village, except for one warrior and his sister (Figure 38). They killed him and he vomited forth his victims alive.

Figure 38: Drawing titled “Seneca Legend of Bare Hill”

A related story from the Kwakiutl of Cape Scott tells of a sea monster that swallowed tribesmen when they were out canoeing. One day, a chief walking near the seashore meets Kosa, a young girl, and asks her to fetch water for him to drink. She is afraid of the sea monster but agrees. As soon as she agreed to obey, she put her Sisiutl belt on, and the vampire instantly killed her. The chief, a wizard, sang an incantation which caused the beast to burst open and disgorge all the people it had devoured. Coming back to life, they limped forward or tripped sideways; their bones were all mixed up. But the chief soon sorted them out, and they became the present Koskimo tribe.

The mixed-up bones of the tribesmen are an important element in the story as the joints are the connecting links between bones and we have seen how the joints must be reconnected by the Spirit line to achieve rebirth.

T’ao-tieh (Glutton), a mythic bear or tiger according to the ancient Chinese, vomited forth “the whole of humanity from the abyss of Chaos (Figure 39).

Figure 39: Vessel depicting T’ao-tieh, China

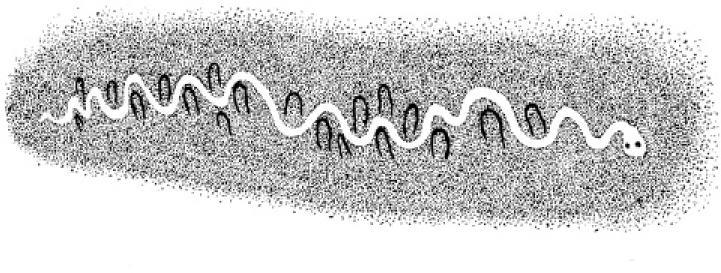

In Australia, the Walbiri describe the mythic serpent Warombi, which travels underground and is the source of life (Figure 40). He swallows initiates and returns them as men.

Figure 40: Pictograph of Warombi, Australia

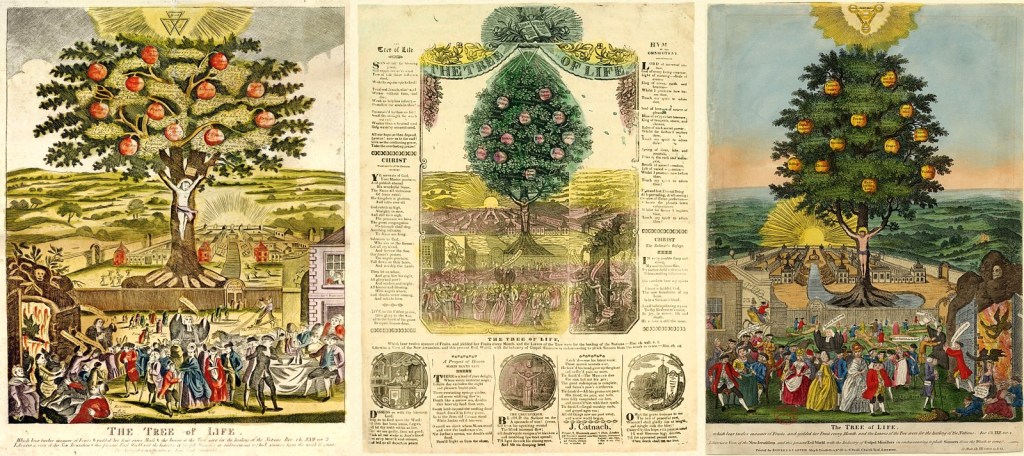

We have two versions of the story in the Judeo-Christian tradition: Jonah is reborn from the belly of the whale crying, “Salvation is of the Lord” and Christ in the Harrowing of Hell, held open the monster’s jaws to release Adam and Eve and all the righteous who had died since the beginning of the world (Figure 41).

Figure 41: Wooden stall carving of the Harrowing of Hell, medieval, France

The challenge is to pass through this primordial creature without being destroyed.1 Rites of initiation prepare the young for the ordeal and ensure a safe passage to the Other World upon death. This generally involves the learning of some kind of esoteric information of which the labyrinth design seems to be a remnant. The relationship of the labyrinth to continuous-line drawings, Cats’ Cradles, and other sacred diagrams is revealed most clearly in its method of construction.

(The “jaws of death” that find later expression in folklore as the clashing rocks, revolving doors, double-edged swords orother guardian pairs protecting the entrance to Heaven. See Coomaraswamy, “Symplegades,” Selected Papers/His Life and Work, vol. II, pp. 521-44, and Guardians of the Sundoor.)

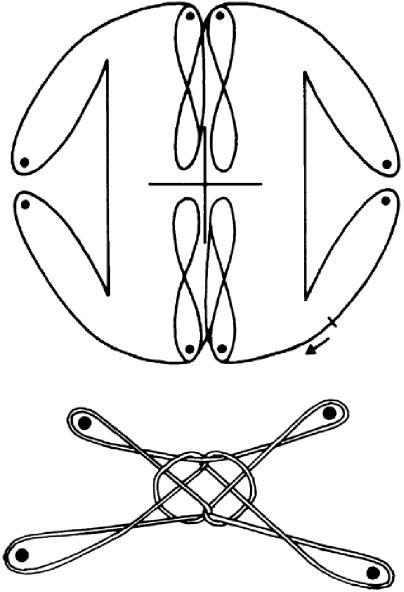

Constructing the Labyrinth

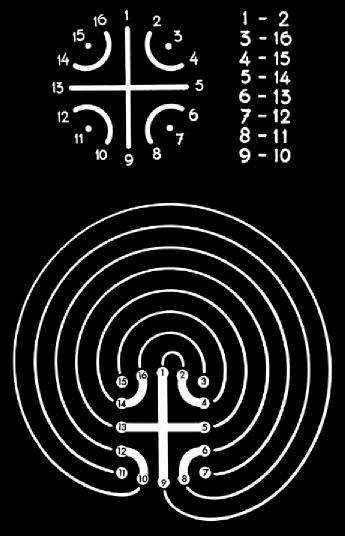

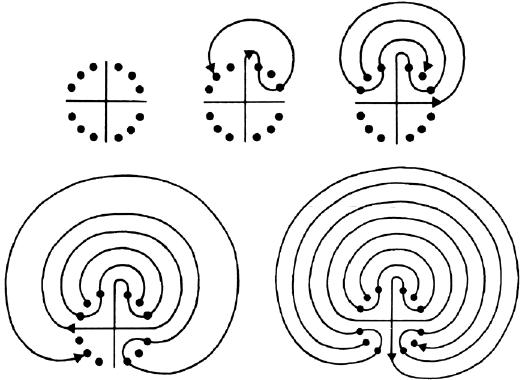

It was the American art historian Carl Schuster who first understood that the key to the labyrinth lay in its method of construction. His extensive research revealed several strategies for drawing the design. The most common employs a preliminary framework built from a cross, four arcs, and four dots within each arc. Once the framework is in place, the rest is simple (Figure 42):

Figure 42: Drawing the labyrinth using a framework

Connect any of the four ends of the cross with the nearest end of an arc, either on the right or on the left; and thereafter connect the following dot with the next position on the other side of the diagram, and so on in orderly progression until the design is completed.

There is a satisfying rhythm to the process as the hand completes successive movements from one side of the diagram to the other. The method is easy to learn and execute, which accounts for its widespread diffusion and survival.

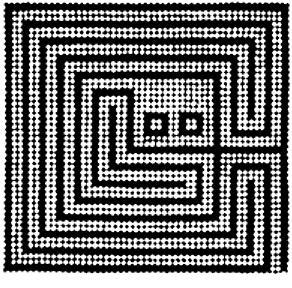

The design is drawn in precisely this way by school children in Finland, Sweden & Ireland; housewives in southern India; Batak sorcerers in Sumatra; and American Indians in southwestern United States, Mexico & Brazil. There is good reason to believe it has been drawn in this way, though not exclusively this way, wherever the motif is known.

Despite its ubiquity, Schuster was not convinced that this was the original method for drawing the labyrinth, feeling that the arcs and dots were really just guidelines for novices who were learning to make the figure. Ever resourceful, he had a friend place an article in the Irish Press (January 9, 1952) asking readers if they knew how to draw the labyrinth depicted on the famous Hollywood Stone, in County Wicklow (Figure 43).

Figure 43: Hollywood Stone, County Wicklow, Ireland

He received twenty responses; all but one used the cross-arc-dots method, but the lone exception proved to be of some importance. A man named William Denton wrote and recalled that as a boy, an elderly Dubliner who knew all kinds of tricks and puzzles had shown him and his friends how to draw the figure using just two lines (Figure 44). He included a drawing illustrating the method. Schuster was intrigued and recalled a prior discussion with John Layard.

The old Dubliner’s method was the method suggested to Schuster by John Layard, when Carl showed him the four-dot method, common in so many parts of the world. …Layard pointed out that one essential feature of all such designs is that they be drawn by means of continuous lines, without raising the hand.

Figure 44: Drawing in a letter from William Denton to Carl Schuster

While the Old Dubliner’s method is not a true continuous-line drawing, it is closer in spirit than the cross-arc-dots method. “To me the Dublin story rings true. It’s disturbing, of course, that we seem to have only one person as a carrier of this tradition, but I still believe it is a bona fide survival of one ancient method of drawing the labyrinth.”2

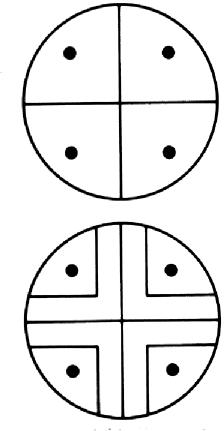

Schuyler Cammann, former Professor of East Asian Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and an old friend of Schuster’s, also felt that the dots and arcs were not part of the original design. He pointed out that the labyrinth could be constructed without the arcs, by using a cross and four dots and drawing four lines (Figure 45).

Figure 45: Four-line method for drawing the labyrinth

This would help to explain the familiar Bronze Age motif of the cross with four dots, often found on personal rings and protective amulets in the Near East and Central Asia (Figure 46). The same designs also appear as rock carvings in Shipaulovi, Arizona, in the same vicinity as labyrinth designs. Cammann thought this might be an abbreviated form of the labyrinth, understood only by those who shared the secret of its construction.

Figure 46: Abbreviated form of labyrinth

A last method for drawing the labyrinth starts with a cross but includes twelve dots, three within each quarter (Figure 47). Four lines are needed to complete the figure, one from each end of the cross.

Figure 47: 12-dot method for drawing the labyrinth

The twelve dots represent the primary joints that make up the human body. In keeping with the sutratman doctrine, the connection of these joints by means of a Spirit-line amounts to a re-animation or “re-membering” of an ancestor figure in whatever form it is conceived (human, reptilian, or avian) (Figure 48).

Figure 48: Joint-marked figures

Dismemberment and Reintegration

It was Carl Schuster’s contention that joint marks—often in the form of faces or eyes—represented the souls of primary ancestors. To achieve reunion with one’s ancestors and thereby qualify for rebirth, all the joints must be connected with a continuous line to form an image of the First One or Original Ancestor.

Thus a genealogical diagram, in the form of a human image, serves as a path to be followed into the Afterworld, by tracing one’s origins, as it were, through the pattern of one’s ancestors, commonly shown as joint marks.

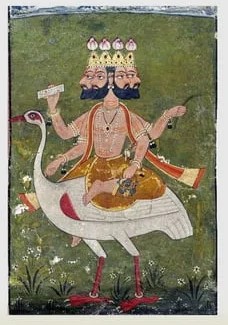

The notion of a dismembered First Ancestor or other religious figure from whom all beings are descended is among the oldest and most widespread of human beliefs. Commenting on the task of the Masonic Masters to “diffuse the light and to gather that which is scattered,” Réne Guénon makes reference to the Hindu tradition.

‘what has been scattered’ is the dismembered body of the primordial Purusha who was divided at the first sacrifice accomplished by the Devas at the beginning, and from whom, by this very division, were born all manifested beings….The Purusha is identical with Prajapati, ‘the lord of beings brought forth’, all of whom have issued forth from him and are thus considered in a certain sense his progeny.

The same story is told of Osiris and Dionysius whose reintegration forms the basis of their respective religious traditions. One need only remember that cannibalism lies at the root of the Vedic and Christian rituals of communion.

By devouring, or as we may phrase it in the present connection, drinking Makha-Soma, Indra appropriates the fallen hero’s desirable qualities by an incorporation that is at the same time sacrificial and Eucharistic, cf. John VI.56, “He that eateth my flesh and drinketh my blood, dwelleth in me, and I in him.”

In earlier times, the “host” was treated as an honored guest, later to be sacrificed and eaten. The Latin word hostis (enemy) is related to hospes (guest), expressing this ambiguity. More directly, the related Sanskrit root ghas means to eat, consume, or destroy.

And what is the essential in the Sacrifice? In the first place, to divide, and in the second to reunite. He being One, becomes or is made into Many, and being Many becomes again or is put together again as One. The breaking of bread is a division of Christ’s body made in order that we may be “all builded together in him.”

The Hebrew Kabalists preserve the tradition in a slightly different but recognizable form.

…though here it is no longer really a question of either sacrifice or of murder, but rather of a kind of ‘disintegration’, the consequences of which are, moreover, the same—it was from the fragmentation of the body of Adam Kadmon that the Universe was formed with all the beings that it contains, so that these are like particles of this body, their reintegration into unity corresponding to the reconstitution of Adam Kadmon, who is ‘Universal Man’..

The re-membering of an ancestor figure is at once an act of personal, social, and cosmic reintegration, as well as a preparation for the life beyond. As a ritual, it found expression in a wide variety of forms.

Joint-marks varied in number, twelve being a complete set (shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees, ankles). Generally fewer were shown. Ideally all were reached in clockwise order. When the last joint was reached, and image was turned and the ritual repeated; or, if the image was a ground drawing, the performer turned, as in hopscotch. The first sequence ‘re-membered’ the Guardian of the Lower World; the second ‘re-membered’ the Guardian of the Upper World.

In terms of social organization, division by twelve was quite common in antiquity. In the Old Testament (Exodus 24:4), Moses erects an altar surrounded by twelve pillars, representing the twelve tribes of Israel. A similar story is repeated in the Book of Joshua (4:1-24) where twelve stones are erected at Gilgal in memory of the crossing of the Jordon on dry land. The Hebrew word gilgal comes from a root word meaning “rolling” or “turning” so that the stones might be considered as spokes in a wheel. There are actually a number of cities so named in the Old Testament and one, north of Bethel, was the scene of Elijah’s departure to heaven in a fiery chariot (2 Kings 2:1-11).

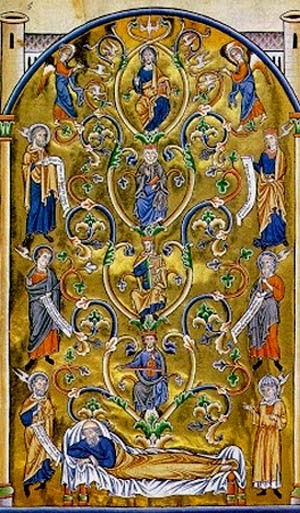

In Kabalistic thought, each Hebrew tribe is associated with a zodiacal sign. The idea of a nation comprising twelve tribes was known to a wide variety of peoples including the Greeks and Celts, and Christ had twelve disciples, adumbrated by the twelve fruits of the Tree of Jesse.

Astronomical and calendrical preoccupations were superimposed on this older idea of dismemberment starting in the 4th millennium. Birth and death mark the passage of time and body joints arranged in a circular fashion became both clocks and calendars.

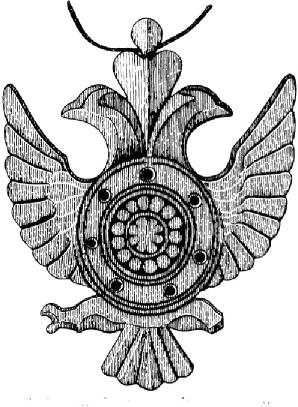

The Christian Yakut of Siberia created peg-calendars within the framework of a two-headed bird (Figure 49). A peg was moved from hole to hole, clockwise, to mark the passage of the week. The circular form was meant to represent the sun, placed in the chest of the solar bird that guards the sun door or entrance to Heaven. The two heads represent darkness and light, night and day, death and life. Clocks were given the same form. The division of the equinoctial day into twelve hours of light and twelve hours of darkness is attributed to the Egyptians but the roots are clearly much older.

Figure 49: Wooden peg calendar, Yakut, Siberia

The same pattern was reflected astronomically as evidenced in the once common belief that the constellations represent a dismembered ancestor, whose body was strewn across the sky. The twelve signs of the zodiac were conceived as body joints that the sun touched in turn to complete a yearly cycle. The cycle was personified as the World Man or World Year in some traditions.

Prajapati is, of course, the Year (samvatsara, passim); as such, his partition is the distinction of times from the principle of Time; his “joints (parvani)” are the junctions of day and night, of the two halves of the month, and of the seasons ….In the same way Ahi-Vrtra, whom Indra cuts up into “joints (parvani, RV iv.19.3, viii.6.13, viii.7.23, etc.)” was originally “jointless” or “inarticulate (aparvah, RV iv.19.3),” i.e., “endless (anantah).”

We find an echo of these ancient ideas in the words of Shakespeare’s Hamlet (Act 1, Scene 5):

The time is out of joint, O cursed spite, That ever I was born to set it right.

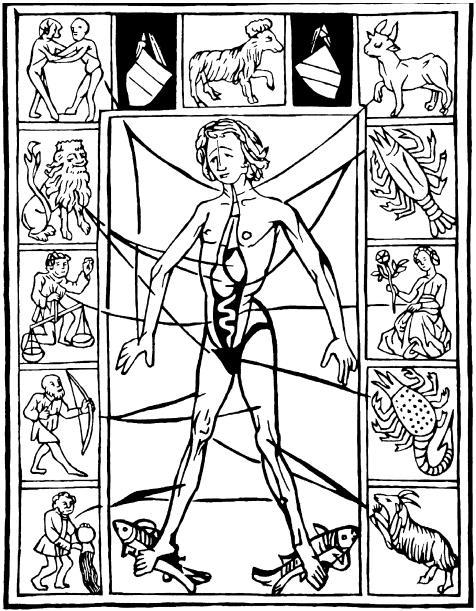

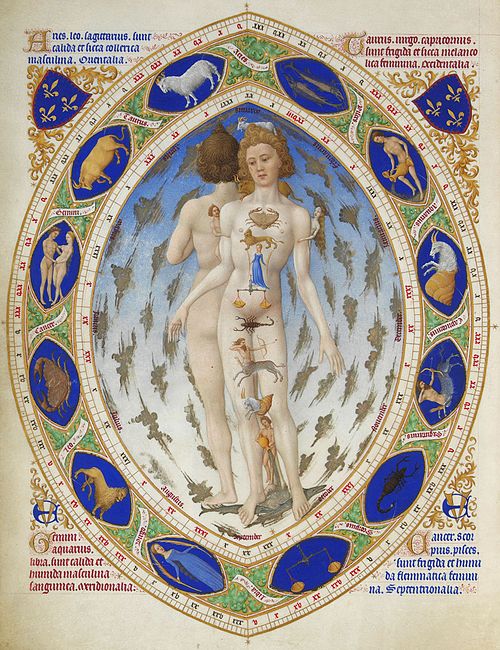

A medieval astrological chart shows the same underlying pattern (Figure 50).

...a cosmic figure marked with twelve zodiacal signs divided into four categories according to Season & Direction. Each sign, representing a ‘temperament’ from its category, marked a location corresponding to a primary joint. Such signs were also conceived as constellations, scattered across the heavens. Re-membering this dismembered figure meant reassembly of its members: the tribal body made One; reembodiment of God and Cosmos.2

Figure 50: Medieval astrological chart, Germany.

Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry

Initiates must know how to complete the labyrinth design—or a related diagram, string figure, or other exercise—in order to ensure a safe passage into the Afterworld and a successful rebirth. This initiation is itself conceived as a kind of death and rebirth for which the participant must be prepared. The figure to be drawn is at once a mythical ancestor, a devouring creature, and the path to the Other World. The monster is the labyrinth in the most basic sense; death the devourer who swallows and regurgitates initiates. To pass through the beast one moves from joint to joint much as one completes the diagram. Many Chinese dragons are joint-marked in this way.

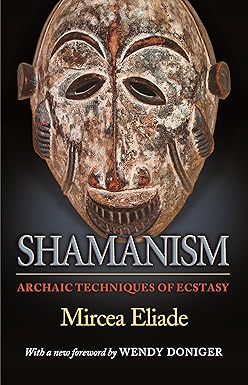

Mircea Eliade describes a Koryak tale “in which a girl lets a cannibal monster eat her so that she can quickly descend to the underworld and return to earth, with all the rest of the cannibal’s victims, before the ‘road of the dead’ closes.” He goes on to note that:

this tale preserves, with astonishing consistency, several initiatory motifs: passage to the underworld by the stomach of a monster; search for innocent victims and their rescue; the road to the beyond that opens and shuts in a few seconds.

Mircea Eliade, Shamanism, pp. 251-252. Eliade also documents the role of ritual dismemberment in many shamanic practices around the world. The shaman’s body must be replaced with a new one to enable entry to the other world and subsequent return to this one.

Because the underlying process is psychological and largely unconscious, the manifestations are varied and in the end constellate into a whole complex of interchangeable vehicles that reflect the same underlying fears, leading such people to rally to multiple, interchangeable causes to vent them. Thus, for example, one of the Malheur militia protesting federal “tyranny,”

Because the underlying process is psychological and largely unconscious, the manifestations are varied and in the end constellate into a whole complex of interchangeable vehicles that reflect the same underlying fears, leading such people to rally to multiple, interchangeable causes to vent them. Thus, for example, one of the Malheur militia protesting federal “tyranny,”

The key lay in letting go of all worldly things, all desires and preconceptions — even one’s image of God himself: “The more completely you are able to draw in your powers to a unity and forget all those things and their images which you have absorbed, and the further you can get from creatures and their images, the nearer you are to this [divine birth] and the readier to receive it.” Then, he said — “in the midst of silence” — God would come within the soul.

The key lay in letting go of all worldly things, all desires and preconceptions — even one’s image of God himself: “The more completely you are able to draw in your powers to a unity and forget all those things and their images which you have absorbed, and the further you can get from creatures and their images, the nearer you are to this [divine birth] and the readier to receive it.” Then, he said — “in the midst of silence” — God would come within the soul.