- Mirrors for princes

Mirrors for princes (Latin: specula principum), or mirrors of princes, form a literary genre, in a loose sense of the word, of political writing during the Early Middle Ages, Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and are part of the broader speculum or mirror literature genre. They occur most frequently in the form of textbooks which directly instruct kings or lesser rulers on certain aspects of rule and behaviour, but in a broader sense the term is also used to cover histories or literary works aimed at creating images of kings for imitation or avoidance. Authors often composed such “mirrors” at the accession of a new king, when a young and inexperienced ruler was about to come to power. One could view them as a species of self-help book – a sort of proto-study of leadership before the concept of a “leader” became more generalised than the concept of a monarchical head-of-state. see more here

To day Anno 2020 these self-help book can be used by any young man to form his heart and mind. A Mirror for the Sons of our Times

- In his book Man and Nature: The Spiritual Crisis in Modern Man

- A lifelong pilgrimage. The Mirror of Jheronimus bosch

Bosch makes art personal, on different levels, and thatmakes him modern. He was one of the first artists in the Low Countries to sign his paintings: ‘Jheronimus bosch’. It was plainly important to him that the works he left behind should be traceable to him. The Haywain (cat. 5) too was signed with his standard signature, affixed like a stamp to the bottom right of the central panel. Bosch also made his art personal, however, for those who look at it. The Haywain is so famous nowadays that it is hard to imagine that when he created it no other painting existed with this subject matter or anything remotely resembling it. We do not know of a single visual precursor for either the Haywain or the Wayfarer. Bosch created an image here that is entirely contemporary – hypermodern art from around 1510–15. Despite their moralizing content, the Haywain and the Wayfarer are not dogmatic paintings; they hold up a mirror to their viewers, to teach them to see themselves better. It was important to Bosch to make his viewers aware of how they bumble their way through life, longing for earthly things. He offered them a personal, exploratory way to realize that if they were to avoid hell and damnation they needed to turn to the good. It is also an important shift in emphasis in the approach to the question of what it means to be a good Christian. Bosch’s work is closely related in this respect to the message of the Devotio Moderna.

Bosch makes art personal, on different levels, and thatmakes him modern. He was one of the first artists in the Low Countries to sign his paintings: ‘Jheronimus bosch’. It was plainly important to him that the works he left behind should be traceable to him. The Haywain (cat. 5) too was signed with his standard signature, affixed like a stamp to the bottom right of the central panel. Bosch also made his art personal, however, for those who look at it. The Haywain is so famous nowadays that it is hard to imagine that when he created it no other painting existed with this subject matter or anything remotely resembling it. We do not know of a single visual precursor for either the Haywain or the Wayfarer. Bosch created an image here that is entirely contemporary – hypermodern art from around 1510–15. Despite their moralizing content, the Haywain and the Wayfarer are not dogmatic paintings; they hold up a mirror to their viewers, to teach them to see themselves better. It was important to Bosch to make his viewers aware of how they bumble their way through life, longing for earthly things. He offered them a personal, exploratory way to realize that if they were to avoid hell and damnation they needed to turn to the good. It is also an important shift in emphasis in the approach to the question of what it means to be a good Christian. Bosch’s work is closely related in this respect to the message of the Devotio Moderna.

According to this spiritual movement, which was particularly strong at the time in the Low Countries, human beings themselves are responsible for their actions: they have to reflect and to make choices, and will be held to account for them personally. ‘Modern Devotion’ also believed that everyone should read the Bible in their own language so they could truly understand the Christian message. Bosch painted in such a way that his paintings likewise have to be ‘read’. We are invited to look, reflect, relate the image to ourselves, and to take its moral to heart. Alongside the familiar positive examples, Bosch introduced exempla contraria – ones to be avoided. In these cases, turning to the good was a question of turning away from evil: a long and arduous road, and a lifelong pilgrimage.

A lone traveller has come from somewhere and plods his way somewhere else in a scene that contains all sorts of elusive elements. Hieronymus Bosch did not create this as an autonomous painting: the round image was originally located on two wings which, when closed, formed a vertical, rectangular surface. The join divided the scene in two, running straight through the traveller and the precise point where the wickerwork pack on his back is fastened shut. The interior of the two wings featured the Ship of Fools on the left and Death and the Miser on the right.

The subject of the now lost central panel is not known. Death is the lone figure’s ultimate destination, as he travels onwards without knowing his future. The road ahead is closed by a gate, while an aggressive dog growls at his heels. The traveller has just passed a house of ill repute, and the landscape in the distance looks barren and desolate. The man’s identity has been left deliberately vague: we cannot see what he has in his pack.

There is nothing to specify that he is a pedlar (as the painting is frequently titled), nor does he wear a pilgrim’s badge. With what few possessions he has, he trudges cautiously, perhaps even hesitantly, through life, looking back over his shoulder and moving ever forwards. Like all of us, he can do nothing else. He is ‘Everyman’ – the literary figure in whom everyone should recognize themselves. The tondo is like a mirror on a wall; the viewer sees life’s pilgrim on his road and like him must choose which course to take without deviating from the true path. Will the traveller open the gate and continue on his way, despite the ox who blocks his path? Or will he wander off into sin and vice? He will ultimately be held to account for the choices he has made, for how he has led his life. Whatever the precise subject of the triptych’s central panel, the message must have been the one Bosch depicts here.

There is nothing to specify that he is a pedlar (as the painting is frequently titled), nor does he wear a pilgrim’s badge. With what few possessions he has, he trudges cautiously, perhaps even hesitantly, through life, looking back over his shoulder and moving ever forwards. Like all of us, he can do nothing else. He is ‘Everyman’ – the literary figure in whom everyone should recognize themselves. The tondo is like a mirror on a wall; the viewer sees life’s pilgrim on his road and like him must choose which course to take without deviating from the true path. Will the traveller open the gate and continue on his way, despite the ox who blocks his path? Or will he wander off into sin and vice? He will ultimately be held to account for the choices he has made, for how he has led his life. Whatever the precise subject of the triptych’s central panel, the message must have been the one Bosch depicts here.

The pig’s trough on the left behind the traveller will immediately have reminded Bosch’s contemporaries of the Parable of the Prodigal Son. Christ told the story of a man who was such a wastrel that he ended up having to tend pigs and envying them their swill. He eventually returned to his father, full of remorse, and was received with great rejoicing (Luke 15:11–32). Yet that is not the story depicted here, either.

The scene Bosch has painted is at once realistic and elusive; it makes the viewer think. All sorts of details contribute to this effect: why is the man wearing a pig’s trotter as an amulet and why is there a cat skin hanging from the spoon on the outside of his pack? Why is there an awl with a loop of thick yarn stuck in the hat he clutches while wearing a chaperon on his head?

There are all sorts of dubious goings-on at the tavern he has just passed: the inverted jug that sticks up from the apex of the gable, the underwear hanging from the window, the little swan on the inn sign, the man urinating round the corner, and the couple canoodling in the doorway are all ominous signs.

An owl high up in the tree has its eye on a titmouse perched a few branches lower, in a visual echo of our own observation of the painting. It is not clear whether the kneeling ox is aware of the magpie at the bottom of the closed gate in front of him, but he probably is. This is all about watching and being watched; human beings too are constantly observed on their life’s path.

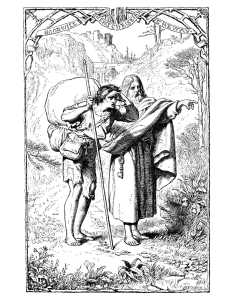

The same idea is expressed more explicitly and with detailed commentary in a contemporary German woodcut, in which the principal character is likewise a traveller. While the devil seeks to waylay him, the human being has to travel onwards as a pilgrim until death tears him away from life. He is surrounded by angels offering good advice, while God – shown high in the middle as the Holy Trinity – looks on and will judge. The image as a whole is presented as a mirror, as emphasized by the title and the text in the banderole: ‘Look, see your reflection and take the message to heart.’ Bosch too has painted a mirror showing the hazardous road through life and the choices that humans must make between good and evil.

mirror-of-understanding Spiegel-der-vernunft :

A Christian pilgrim, identified by his hat, staff, and knapsack, is shown in the mirror. He walks the road of life, symbolized by a perilous, roughly hewn bridge with branch stubs to trip him up. The devil pulls him backward, toward worldly pleasures, while at the far end Death, with a bow and a clock, measures his allotted time. Beyond Death there is resurrection and the Last Judgment. Below the bridge is a grave, and below that a Hellmouth, while at the top of the image the Trinity are shown, along with the Virgin and the Fountain of Life. Behind the medallion with the Trinity are ten spheres, the lowest showing the Moon, Sun, and stars while the other nine illustrate choirs of angels. A crucifix links this heavenly scene with the tableaux of the mirror, while four angels give advice. The central image is related to Bosch’s The Path of Life (the exterior image on The Haywain Triptych) and his Wayfarer tondo, as well as Durer’s Knight, Death, and the Devil.

-

- The Ship of Fools

The ship of fools is an allegory, originating from Book VI of Plato’s Republic, about a ship with a dysfunctional crew:

The ship of fools is an allegory, originating from Book VI of Plato’s Republic, about a ship with a dysfunctional crew:

Imagine then a fleet or a ship in which there is a captain who is taller and stronger than any of the crew, but he is a little deaf and has a similar infirmity in sight, and his knowledge of navigation is not much better. The sailors are quarreling with one another about the steering––every one is of the opinion that he has a right to steer, though he has never learned the art of navigation and cannot tell who taught him or when he learned, and will further assert that it cannot be taught, and they are ready to cut in pieces any one who says the contrary. They throng about the captain, begging and praying him to commit the helm to them; and if at any time they do not prevail, but others are preferred to them, they kill the others or throw them overboard, and having first chained up the noble captain’s senses with drink or some narcotic drug, they mutiny and take possession of the ship and make free with the stores; thus, eating and drinking, they proceed on their voyage in such a manner as might be expected of them. Him who is their partisan and cleverly aids them in their plot for getting the ship out of the captain’s hands into their own whether by force or persuasion, they compliment with the name of sailor, pilot, able seaman, and abuse the other sort of man, whom they call a good-for-nothing; but that the true pilot must pay attention to the year and seasons and sky and stars and winds, and whatever else belongs to his art, if he intends to be really qualified for the command of a ship, and that he must and will be the steerer, whether other people like or not––the possibility of this union of authority with the steerer’s art has never seriously entered into their thoughts or been made part of their calling. Now in vessels which are in a state of mutiny and by sailors who are mutineers, how will the true pilot be regarded? Will he not be called by them a prater, a star-gazer, a good-for-nothing

When the triptych opens, the mirror ‘breaks’ and its contents – or rather the view it offers of them – are shown inside. We will begin with what was once the left wing, with its boatload of merrymakers, surrounded by drunkards and lovers. These are people in the flush of their lives, concerned with neither God nor his commandments. They have given themselves over to eating, drinking, swimming and lovemaking, and their most pressing concern seems to be the pie balanced on the head of one of the swimmers, which they are eager to get onto dry land in one piece. Death still seems a long way away. None of the figures realizes what Sebastian Brant declared in the prologue to his Stultifera Navis ( Ship of Fools , 1497), namely that ‘In the ship, we are separated but three fingers’ breadth from death.’

When the triptych opens, the mirror ‘breaks’ and its contents – or rather the view it offers of them – are shown inside. We will begin with what was once the left wing, with its boatload of merrymakers, surrounded by drunkards and lovers. These are people in the flush of their lives, concerned with neither God nor his commandments. They have given themselves over to eating, drinking, swimming and lovemaking, and their most pressing concern seems to be the pie balanced on the head of one of the swimmers, which they are eager to get onto dry land in one piece. Death still seems a long way away. None of the figures realizes what Sebastian Brant declared in the prologue to his Stultifera Navis ( Ship of Fools , 1497), namely that ‘In the ship, we are separated but three fingers’ breadth from death.’

- Books of Spiritual Chivalry

Since the “Green Knight” must be recognized as yet another “mysterious glimpse” of al-Khidr; some reasons for this are given in the introduction to The Royal Book of Spiritual Chivalry. (Futuwwat-nama-yi sultani)

Since the “Green Knight” must be recognized as yet another “mysterious glimpse” of al-Khidr; some reasons for this are given in the introduction to The Royal Book of Spiritual Chivalry. (Futuwwat-nama-yi sultani)

ON FUTUWWAH:

Futuwwah is the way of the fata. In Arabic, fata literally means a handsome, brave youth. After the enlightenment of Islam, following the use of the word in the Holy Koran, fata (plural: fityan) came to mean the ideal, noble, and perfect man whose hospitality and generosity would extend until he had nothing left for himself; a man who would give all, including his life, for the sake of his friends. According to the Sufis, Futuwwah is a code of honorable conduct that follows the example of the prophets, saints, sages, and the intimate friends and lovers of Allah.

The traditional example of generosity is the prophet Abraham, peace be upon him, who readily accepted the command to sacrifice his son for Allah’s sake. He is also a

The traditional example of generosity is the prophet Abraham, peace be upon him, who readily accepted the command to sacrifice his son for Allah’s sake. He is also a

model of hospitality who shared his meals with guests all his life and never ate alone. The prophet Joseph, peace be upon him, is an example of mercy, for he pardoned his brothers, who tried to kill him, and a model of honor, for he resisted the advances of a married woman, Zulaykha, who was feminine beauty personified. The principles of character of the four divinely guided caliphs, the successors of the Prophet

Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him, also served as guides to Futuwwah; the loyalty of Abu Bakr, the justice of ‘Umar, the reserve and modesty of ‘Uthman, and the bravery of ‘Ali, may Allah be pleased with them all.

The all-encompassing symbol of the way of Futuwwah is the divinely guided life and character of the final prophet, Muhammad Mustafa, may Allah’s peace and blessings be upon him, whose perfection is the goal of Sufism. The Sufi aims to abandon all improper behavior and to acquire and exercise, always and under all circumstances, the best behavior proper to human beings; for God created man “for Himself” as His “supreme creation,” “in the fairest form.” As He declares in His Holy Koran, “We have indeed honored the children of Adam.”

- Erasmus’s Education of a Christian Prince

The Education of a Christian Prince (Latin: Institutio principis Christiani) is a Renaissance “how-to” book for princes, by Desiderius Erasmus, which advises the reader on how to be a “good Christian” prince. The book was dedicated to Prince Charles, who later became Habsburg Emperor Charles V. Erasmus wrote the book in 1516, the same year that Thomas More finished his Utopia and three years after Machiavelli had written his advice book for rulers Il Principe. The Principe, however, was not published until 1532, 16 years later.

The Education of a Christian Prince (Latin: Institutio principis Christiani) is a Renaissance “how-to” book for princes, by Desiderius Erasmus, which advises the reader on how to be a “good Christian” prince. The book was dedicated to Prince Charles, who later became Habsburg Emperor Charles V. Erasmus wrote the book in 1516, the same year that Thomas More finished his Utopia and three years after Machiavelli had written his advice book for rulers Il Principe. The Principe, however, was not published until 1532, 16 years later.

Erasmus stated that teachers should be of gentle disposition and have unimpeachable morals. A good education included all the liberal arts. Like the Roman educator Quintilian, Erasmus was against corporal punishment for unruly students. He stressed the student must be treated as an individual. Erasmus attempted throughout the work to reconcile the writers of antiquity with the Christian ethics of his time. The text was written in part to secure Erasmus a position as Prince Charles’s tutor. See more here

The Education of a Christian Prince complete text here

- Erasmus: The Handbook of a Christian Knight

The Handbook of a Christian Knight (Latin: Enchiridion militis Christiani), sometimes translated as The Manual of a Christian Knight or The Handbook of the Christian Soldier, is a work written by Dutch scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam in 1501,[1] and was first published in English in 1533 by William Tyndale.

During a stay in Tournehem, a castle near Saint-Omer in the north of modern-day France, Erasmus encountered an uncivilized, yet friendly soldier who was an acquaintance of Battus, Erasmus’ close friend. On the request of the soldier’s pious wife, who felt slighted by her husband’s behaviour, Battus asked Erasmus to write a text which would convince the soldier of the necessity of mending his ways, which he did. The resulting work was eventually re-drafted by Erasmus and expanded into the Enchiridion militis Christiani.[2] The Enchiridion is an appeal on Christians to act in accordance with the Christian faith rather than merely performing the necessary rites. It became one of Erasmus’ most influential works.

on The Manual of a Christian Knight [1501]

Desiderius Erasmus was a Catholic priest and theologian who clearly had Christ in mind when he penned it in 1501. Although it is over 500 years old, I hope you will appreciate the relevance today of these 22 rules in Erasmus’ Manual of a Christian Knight.

The mortal world a field is of battle

Which is the cause that strife doth never fail

Against man, by warring of the flesh

With the devil, that always fighteth fresh

The spirit to oppress by false envy;

The which conflict is continually

During his life, and like to lose the field.

But he be armed with weapon and shield

Such as behoveth to a christian knight,

Where God each one, by his Christ chooseth right

Sole captain, and his standard to bear.

Who knoweth it not, then this will teach him here

In his brevyer, poynarde, or manual

The love shewing of high Emanuell.

In giving us such harness of war

Erasmus is the only furbisher

Scouring the harness, cankered and adust

Which negligence had so sore fret with rust

Then champion receive as thine by right

The manual of the true christian knight.

– Desiderius Erasmus

Here some of the 22 rules:

- We must watch and look about us evermore while we be in this life.

- Of the weapons to be used in the war of a Christian man.

- That the first point of wisdom is to know thyself, and of two manner wisdoms, the true wisdom, and the apparent.

- Of the outward and inward man.

- Of the diversity of affections.

- Of the inward and outward man and of the two parts of man, proved by holy scripture.

- Of three parts of man, the spirit, the soul, and the flesh.

- Certain general rules of true christian living.

- Against the evil of ignorance.

***********************

- The legacy of John Bunyan,

“Well then sinner, what sayest thou? Where is thy heart? Wilt thou run? Art thou resolved to strip? Get into the way; run apace and hold out to the end; and the Lord give thee a prosperous journey. Farewell,” John Bunyan

John Bunyan (1628-88) was arguably one of the most influential writers in human history. Consider the fact that after the undoubted supremacy in circulation of the English Bible, Bunyan’s classic allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress, has commonly ranked second. This has led it to be called “the second best book in all the world.”

Even secular critics have agreed that this uneducated mender of pots and pans was a writer of uncommon genius. Raised during the turbulent seventeenth century in England, following conversion from an unsavory past, Bunyan began to preach and receive a welcome hearing. His first venture at writing at this time was a vigorous response to Quaker doctrine. Staunchly nonconformist, he was imprisoned for 12 years in the Bedford County jail for refusing to remain silent. See more here

The Pilgrim’s Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come

First Part

First Part

The entire book is presented as a dream sequence narrated by an omniscient narrator. The allegory’s protagonist, Christian, is an everyman character, and the plot centres on his journey from his hometown, the “City of Destruction” (“this world”), to the “Celestial City” (“that which is to come”: Heaven) atop Mount Zion. Christian is weighed down by a great burden—the knowledge of his sin—which he believed came from his reading “the book in his hand” (the Bible). This burden, which would cause him to sink into Hell, is so unbearable that Christian must seek deliverance. He meets Evangelist as he is walking out in the fields, who directs him to the “Wicket Gate” for deliverance. Since Christian cannot see the “Wicket Gate” in the distance, Evangelist directs him to go to a “shining light,” which Christian thinks he sees. Christian leaves his home, his wife, and children to save himself: he cannot persuade them to accompany him. Obstinate and Pliable go after Christian to bring him back, but Christian refuses. Obstinate returns disgusted, but Pliable is persuaded to go with Christian, hoping to take advantage of the Paradise that Christian claims lies at the end of his journey. Pliable’s journey with Christian is cut short when the two of them fall into the Slough of Despond, a boggy mire-like swamp where pilgrims’ doubts, fears, temptations, lusts, shames, guilts, and sins of their present condition of being a sinner are used to sink them into the mud of the swamp. It is there in that bog where Pliable abandons Christian after getting himself out. After struggling to the other side of the slough, Christian is pulled out by Help, who has heard his cries and tells him the swamp is made out of the decadence, scum, and filth of sin, but the ground is good at the narrow Wicket Gate. Read more here.

Second Part

The Second Part of The Pilgrim’s Progress presents the pilgrimage of Christian’s wife, Christiana; their sons; and the maiden, Mercy. They visit the same stopping places that Christian visited, with the addition of Gaius’ Inn between the Valley of the Shadow of Death and Vanity Fair, but they take a longer time in order to accommodate marriage and childbirth for the four sons and their wives. The hero of the story is Greatheart, a servant of the Interpreter, who is the pilgrims’ guide to the Celestial City. He kills four giants called Giant Grim, Giant Maul, Giant Slay-Good, and Giant Despair and participates in the slaying of a monster called Legion that terrorizes the city of Vanity Fair. The passage of years in this second pilgrimage better allegorizes the journey of the Christian life. By using heroines, Bunyan, in the Second Part, illustrates the idea that women, as well as men, can be brave pilgrims. Read more here.

The Holy War Made by King Shaddai Upon Diabolus, to Regain the Metropolis of the World, Or, The Losing and Taking Again of the Town of Mansoul is a 1682 novel by John Bunyan. This novel, written in the form of an allegory, tells the story of the town “Mansoul” (Man’s soul). Though this town is perfect and bears the image of Shaddai (Almighty), it is deceived to rebel and throw off his gracious rule, replacing it instead with the rule of Diabolus. Though Mansoul has rejected the Kingship of Shaddai, he sends his son Emmanuel to reclaim it.

The Holy War Made by King Shaddai Upon Diabolus, to Regain the Metropolis of the World, Or, The Losing and Taking Again of the Town of Mansoul is a 1682 novel by John Bunyan. This novel, written in the form of an allegory, tells the story of the town “Mansoul” (Man’s soul). Though this town is perfect and bears the image of Shaddai (Almighty), it is deceived to rebel and throw off his gracious rule, replacing it instead with the rule of Diabolus. Though Mansoul has rejected the Kingship of Shaddai, he sends his son Emmanuel to reclaim it.

In the city there were three esteemed men, who, by admitting Diabolus to the city, lost their previous authority. The eyes of “Understanding”, the mayor, are hidden from the light. “Conscience”, the recorder, has become a madman, at times sinning, and at other times condemning the sin of the city. But worst of all is “Lord Willbewill,” whose desire has been completely changed from serving his true Lord, to serving Diabolus. With the fall of these three, for Mansoul to turn back to Shaddai of their own will, is impossible. Salvation can come only by the victory of Emmanuel. The entire story is a masterpiece of Christian literature, describing vividly the process of the fall, conversion, fellowship with Emmanuel, and many more intricate doctrines. Read more here

THE SAINTS’ KNOWLEDGE OF CHRIST’S LOVE

This treatise is admirably adapted to warn the thoughtless—break the stony heart— convince the wavering—cherish the young inquirer—strengthen the saint in his pilgrimage, and arm him for the good fight of faith—and comfort the dejected, doubting, despairing Christian. It abounds with ardent sympathy for the broken-hearted, a cordial suited to every wounded conscience; while, at the same time, it thunders in awful judgment upon the impenitent and the hypocritical professor: wonders of grace to God belong, for all these blessings form but a small part of the unsearchable riches. Read more here.

This treatise is admirably adapted to warn the thoughtless—break the stony heart— convince the wavering—cherish the young inquirer—strengthen the saint in his pilgrimage, and arm him for the good fight of faith—and comfort the dejected, doubting, despairing Christian. It abounds with ardent sympathy for the broken-hearted, a cordial suited to every wounded conscience; while, at the same time, it thunders in awful judgment upon the impenitent and the hypocritical professor: wonders of grace to God belong, for all these blessings form but a small part of the unsearchable riches. Read more here.

**********

- Mirrors for Princes and Sultans:

Advice on the Art of Governance in the Medieval Christian and Islamic Worlds

Among the most significant forms of political writing to emerge from the medieval

period are texts offering advice to kings and other high-ranking officials. Books of

counsel varied considerably in their content; scholars agree, however, that such texts

reflected the political exigencies of their day. As a result, writings in the “mirrors

for princes” tradition offer valuable insights into the evolution of medieval modes of

governance. While European mirrors (and Machiavelli’s Prince in particular) have

been extensively studied, there has been less scholarly examination of a parallel political

advice literature emanating from the Islamic world. We compare Muslim and Christian

advisory writings from the medieval period using automated text analysis and identify

four conceptually distinct areas of concern common to both Muslim and Christian

polities. While political advice givers in both traditions faced the challenge of “speaking

truth to power,” Muslim and Christian writers diverged — to some degree — in how

they offered advice to their powerful patrons. While Christian authors tended to rely

heavily on crafting a picture of the “ideal” prince, Muslim writers made greater use

of fables and analogies to the natural world as they sought to convey wisdom about

the art of governance. Christian authors became even more direct in their engagement

with political themes over time. We offer a tentative explanation for these trends. Read more here

- Goethe

Goethe’s West-östlicher Divan marks a literary encounter between German and Persian literature which began in 1814. In the spring of that year, Goethe received a German translation of Ḥāfeẓ’s divān in two volumes from the publisher Cotta of Stuttgart (Bohnenkamp and Bosse, p. 308). The translator was the Austrian Orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774-1856), whose translations and commentaries played a major role in acquainting Germans with the East. Hammer’s translation of the divān broadened and expanded the knowledge of the Orient which Goethe had acquired in his youth, so that he could now, at the age of 65, devote himself more intensively to the East, and predominantly to Persia.

Here About Al Gazali “To my Beloved Son , translated by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall:

Every part of my little book demonstrates how much I owe to this worthy man. I had long been aware of Hafiz and his poems, but nothing I had found in literature, travel books, journals, or other documents had conveyed any sense of the merits of this extraordinary man. When I finally encountered a complete translation of all his works in the spring of 1813 [1814], I felt I had grasped his inner nature with a special affinity and tried to establish a relation to him through my own production. This collegial activity helped me get through precarious times and allowed me finally to enjoy in the most agreeable way the fruits of the peace I attained.

For some years I had known in a general way about the flourishing enterprise of the Fundgruben [Oriental Sources; see Bibliography], but now came the time for me to take full advantage of it. This work pointed in many directions, arousing and satisfying the needs of the time. Here again experience confirmed a basic truth: our contemporaries aid us most rewardingly when we are willing to apply their worthy contributions with cordial gratitude. Well-informed men teach us about the

past, indicate starling points for present ventures, and point out the next road we may take.

Fortunately the splendid Oriental Sources is now being supplemented with the same zeal, and though I have to backtrack to keep up, I always gladly return with renewed interest to what is so freshly enjoyable and useful from many perspectives.

One thing should be noted: I could have used this important collection even more efficiently if the editors, whose efforts and contributions are targeted toward specialists, had also focused attention on laymen and amateurs. Had they prefaced at least some of the articles with brief introductions about historical contexts, people, and places, they would have spared an eager student many a wearying, distracting search.

But whatever that presentation left to be desired is now amply compensated by everything I was taught about the history of Persian poetry in such an invaluable work. I will gladly admit that as early as 1814, when the Gijttinger Aneigen offered a tentative account of the book’s contents, I immediately organized my studies according to the given rubrics, which profited me greatly. When the whole work, so impatiently awaited, finally appeared, I found myself at once in a familiar world, whose circumstances I could note and observe in detail, no longer in a generalized way as if through shifting, misty veils. I hope you will be reasonably satisfied with the way I have used this work, intending to attract those who might otherwise never have heard of such an abundante of treasures.

Surely we have now acquired a basis on which to display the magnificence of Persian literature. Using this model we may similarly elevate the positron and advance the appreciation of other literatures. It would remain highly desirable to preserve chronological order and not attempt to arrange the poetry according to its different genres. With Oriental poets everything is too interwoven to allow items to

be isolated. The character of the era and of the poet in his era is the only enlightening context to enliven each poet. I recommend that my method continue to be used.

I hope readers will acknowledge the special merit of the splendid “Schirin” [Hammer, “Schirin”], the amiably and earnestly instructive “Clover leaf” [Hammer, “Morgenlndisches Kleeblatt”] which I have placed with such pleasure at the end of this work.

See here also his translation of “O Kind “ to my Beloved Son “ of Gazali

Dear Beloved Son / Ayyuhal Walad Al Ghazali

“I seek Allahs refuge from the knowledge which is of no benefit”. This disciple of Imam Ghazali (RA) kept thinking along these lines for a few days and then wrote a letter to Imam Ghazali (RA) with the view of getting an answer to his dilemma along with some other questions. Furthermore, he asked in his letter to Imam Ghazali (RA) for some advice and to teach him a supplication that he could always recite. He wrote in his letter that although Imam Ghazali (RA) has written numerous books on this issue,this weak individual is in need of something that he could always study and always act upon its injunctions. In reply to his letter, Imam Ghazali (RA) sent him the following advices. free download

“I seek Allahs refuge from the knowledge which is of no benefit”. This disciple of Imam Ghazali (RA) kept thinking along these lines for a few days and then wrote a letter to Imam Ghazali (RA) with the view of getting an answer to his dilemma along with some other questions. Furthermore, he asked in his letter to Imam Ghazali (RA) for some advice and to teach him a supplication that he could always recite. He wrote in his letter that although Imam Ghazali (RA) has written numerous books on this issue,this weak individual is in need of something that he could always study and always act upon its injunctions. In reply to his letter, Imam Ghazali (RA) sent him the following advices. free download

– Lettre au disciple – Ayyuhal Walad Al Ghazali

– Lettre au disciple – Ayyuhal Walad Al Ghazali

La “lettre au disciple” (ayyuha al walad) de l’Imam Abu Hamid al Ghazali est l’un de ses derniers ouvrages. Il répond sous forme d’épître à un de ses élèves qui l’avait prié de lui apporter des éclaircissements sur des points de doctrine et sur certains points qui relèvent de la science du dévoilement. free download

- Goethe about The Book of Kabus ( Mirror for Princes)

An important influence on my studies, which I thankfully acknowledge, is that of the prelate von Diez ([HEINRICH FRIEDRICH] VON DIEZ [1786-1817]). At the time when I was carefully researching Oriental poetry, the Book of Kabus came into my hands. It seemed so important that I devoted much time to it and invited many friends to have a look at it. Through a traveler I transmitted my sincere thanks to that estimable man from whom I had learned so much. He kindly sent me in return a little book about tulips. I had a sheet of silky paper which I directed to be adorned with a splendid golden floral design. On that sheet I wrote the following poem:

How to be prudent in our wanderings – Uphill, or down, departing from a throne — Dealing with people, horses, other things ¬All a king teaches to his son — you’ve shown. Through your fine gift, such knowledge now is ours. To that, you even add a tulip bloom! Were this gold frame not narrowing my powers, To sing your praise I would need endless room.

And so developed a conversation in letters, which the worthy man continued, in an almost illegible hand, amid sufferings and pains, until the end of his life.

Since I have so far become acquainted with the customs and history of the Orient only in a general way, and with its languages not at all, such kindness was most important to me. Because I was working in a planned, methodical way, I needed accessible information that would have required time and energy to locate in books. So when in doubt I consulted him and always got an adequate, practical reply to any question. The content of these letters would make them worthy of printing; they would serve as a monument to his knowledge and benevolence. As I knew his strict and distinctive cast of mind, I was careful not to mention certain topics. But, quite in contrast to his usual mode of thought, when I wished to learn about the personality of Nasreddin Khodja, merry traveland tent-companion of the global conqueror Timur, von Diez obligingly translated for me some of the anecdotes. These showed once again that many audacious fairytales, which Westerners have treated in their own way, have their origin in the Orient but in being transformed have lost their special coloring, their true, appropriate tone. (read mor here)