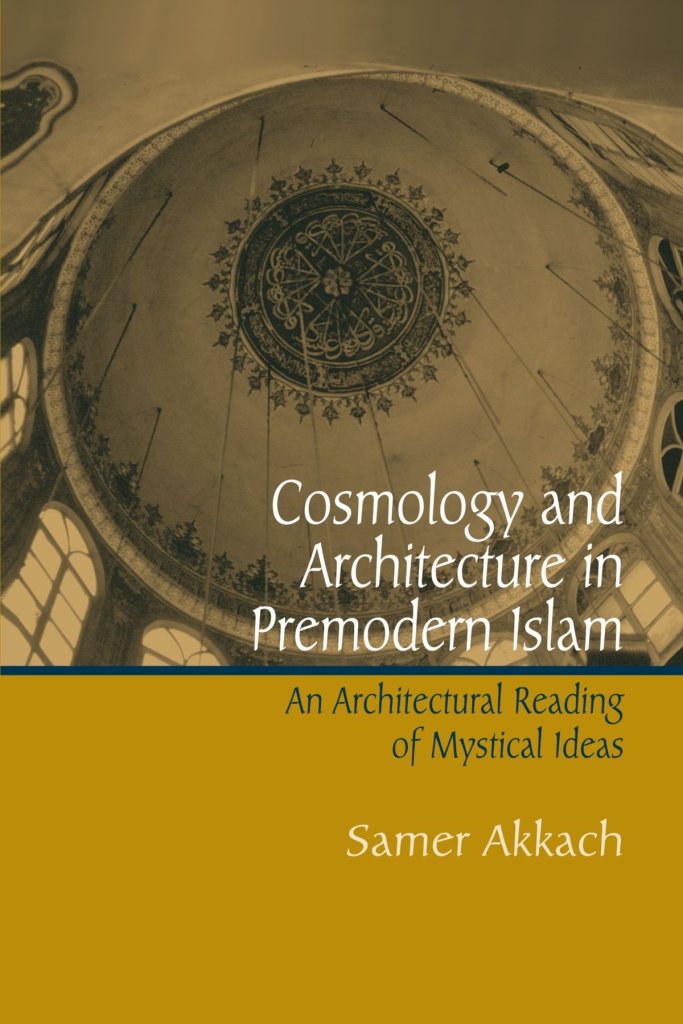

- Ibn ‘Arabî and Islamic mysticism:

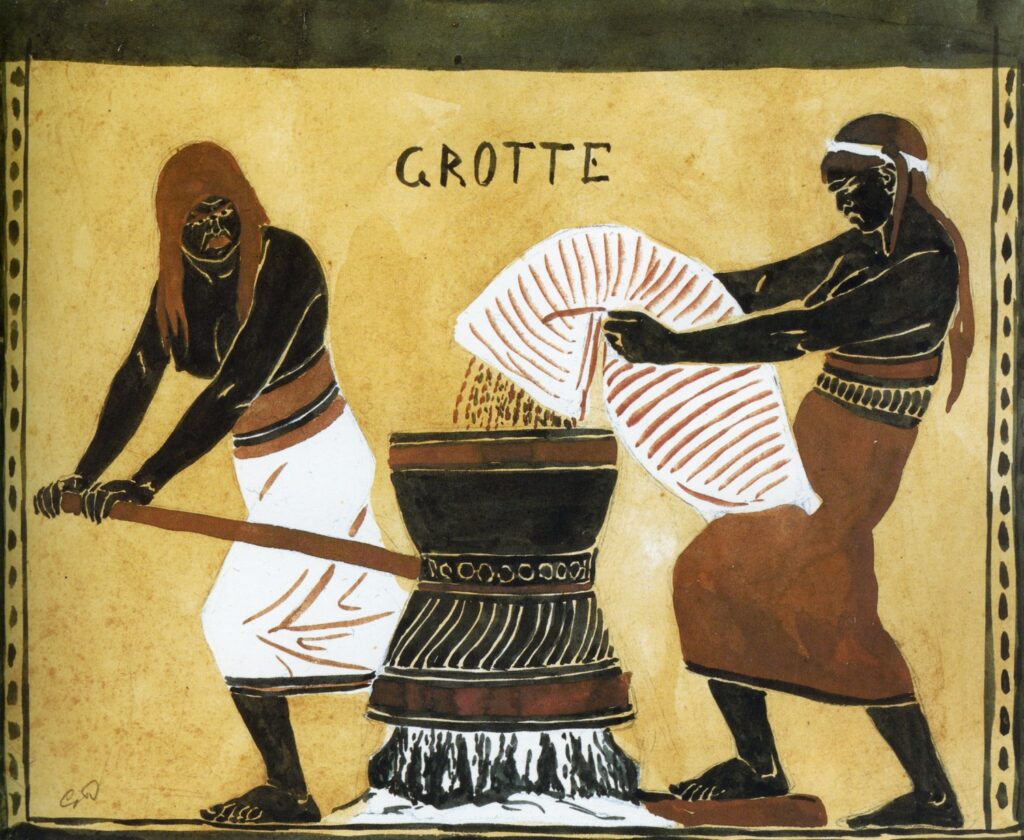

According to Professor Henry Corbin, one of the 20th century’s most prolific scholars of Islamic mysticism, Ibn ‘Arabî (1165–1240) was “a spiritual genius who was not only one of the greatest masters of Sufism in Islam, but also one of the great mystics of all time.” see The humandivinedotorg-Golgonooza

Imagination (khayâl), as Corbin has shown, plays a major role in Ibn ‘Arabî’s writings. In the Openings, for example, he says about it, “After the knowledge of the divine names and of self-disclosure and its all-pervadingness, no pillar of knowledge is more complete”.

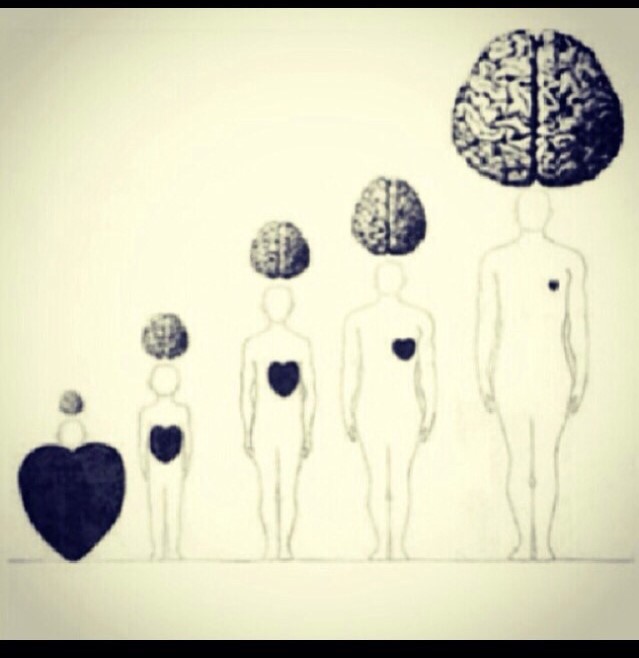

He frequently criticizes philosophers and theologians for their failure to acknowledge its cognitive significance. In his view, ‘aql or reason, a word that derives from the same root as ‘iqâl, fetter, can only delimit, define, and analyze. It perceives difference and distinction, and quickly grasps the divine transcendence and incomparability. The term “al-‘aql” in Arabic is derived from the root word “ql,” which means to bind. In Islamic thought, it is used to describe the faculty that connects individuals to God. It is usually translated in English as intellect, intelligence, reason or rational faculty. Read more here

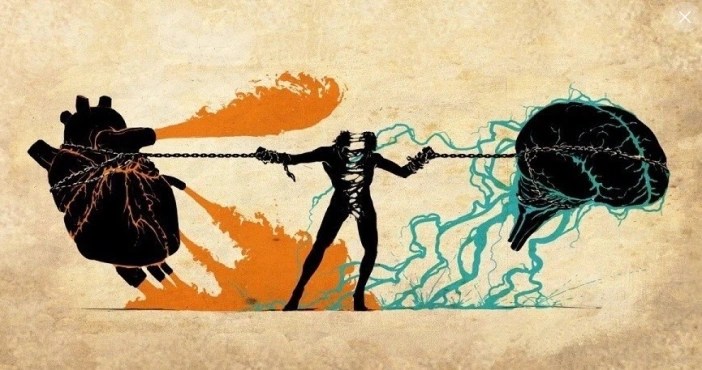

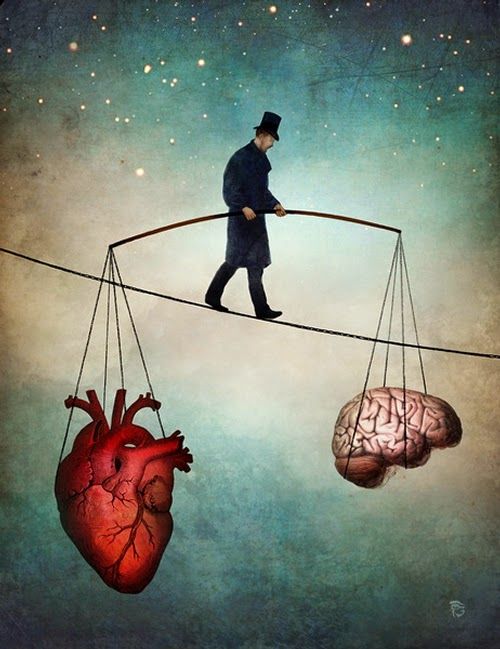

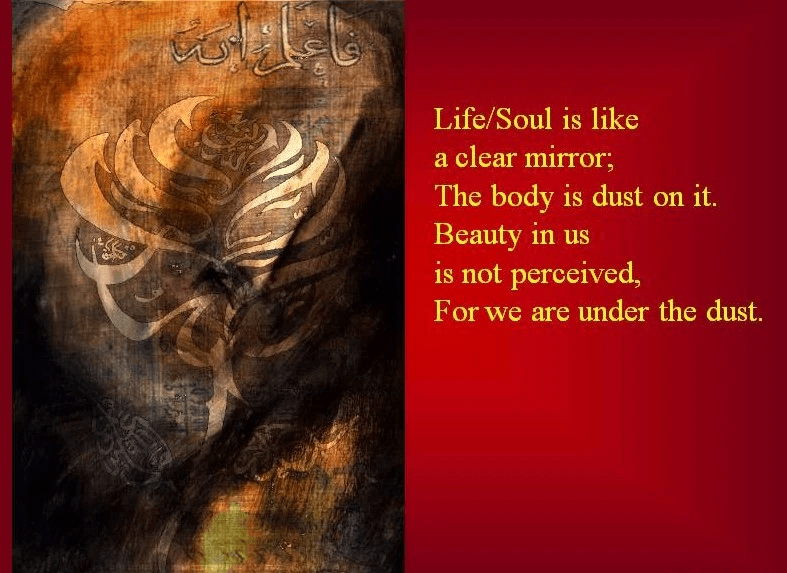

In The Alchemy of Happiness, Al-Ghazzali describes the human being in the following metaphor:

The body is like a country. The artisans are like the hands, feet, and various parts of the body. Passion is like the tax collector. Anger or rage is like the sheriff. The heart is the king. Intellect is the prime minister. Passion, like a tax collector using any means, tries to extract everything. Rage and anger are severe, harsh and punishing like the police and want to destroy or kill. The ruler not only needs to control passion and rage, but also the intellect and must keep a balance among all these forces. If the intellect becomes dominated by passion or anger, the country will be in ruin and the ruler will be destroyed.

Rumi echoes the same theme when he describes the role of Conscious Reason in keeping a balance among our various desires:

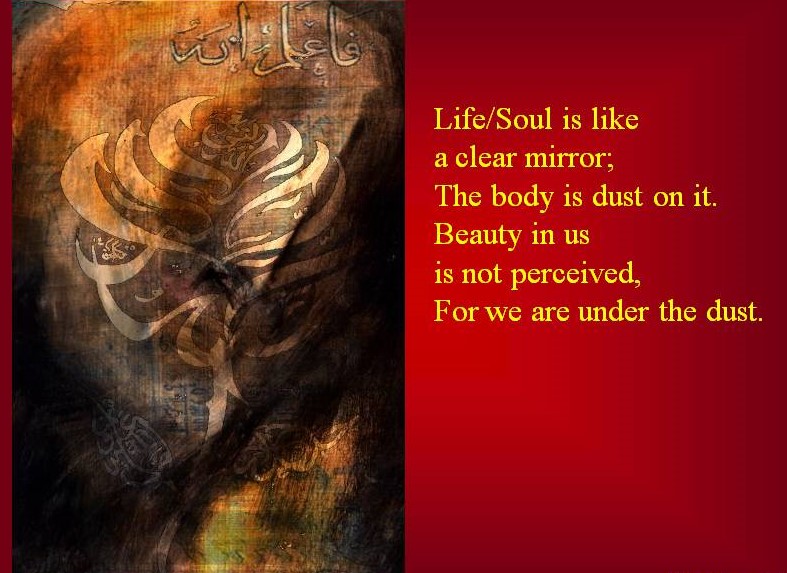

God has given you Conscious Reason

as an instrument for polishing the heart until its surface reflects.

But you, prayerless, have bound the polisher

and freed the two hands of sensuality.

If you can restrain sensuality, you will free the polisher….

Until now you have made the water turbid, but no more.

Do not stir it up, let the water become clear enough

for the moon and stars to be reflected in it.

For the human being is like the water of a river:

when muddied you cannot see the bottom.

The river is full of jewels and pearls.

Do not cloud the water that was pure and free.

[Mathnawi IV, 2475-2477, 2480-2482]

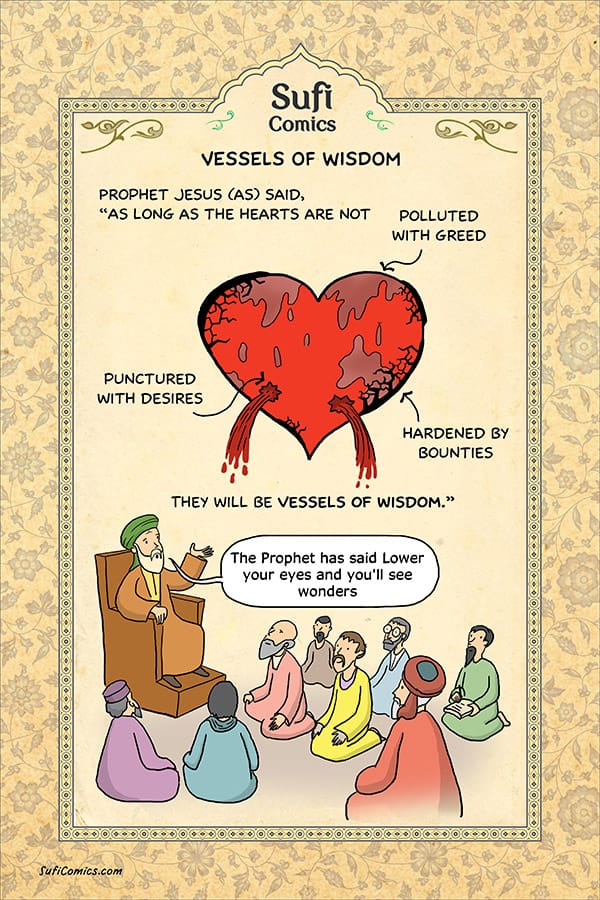

The attractions of the outer world are only a small distraction compared to the promptings of egoism which distract us from within. Bayazid Bistami said, “The contraction of the heart comes with the expansion of the ego, and vice versa.”

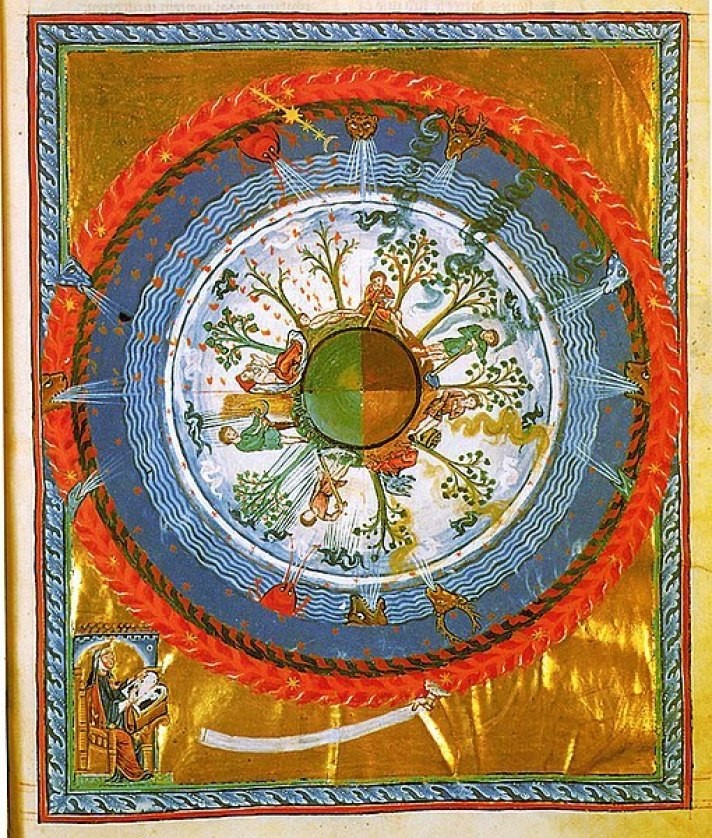

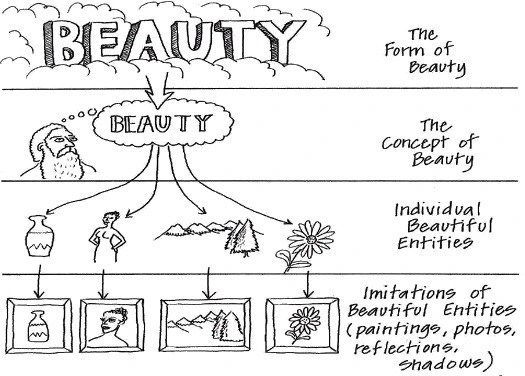

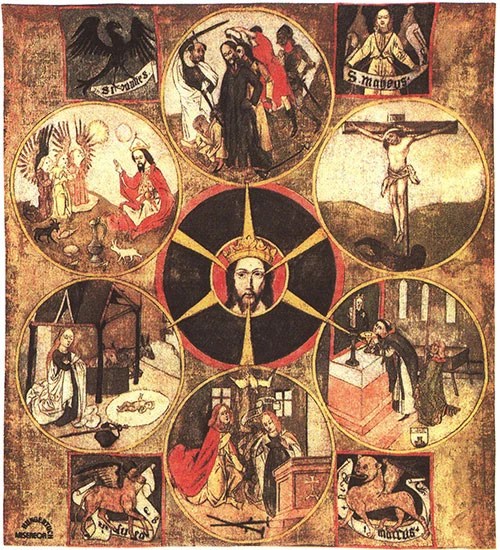

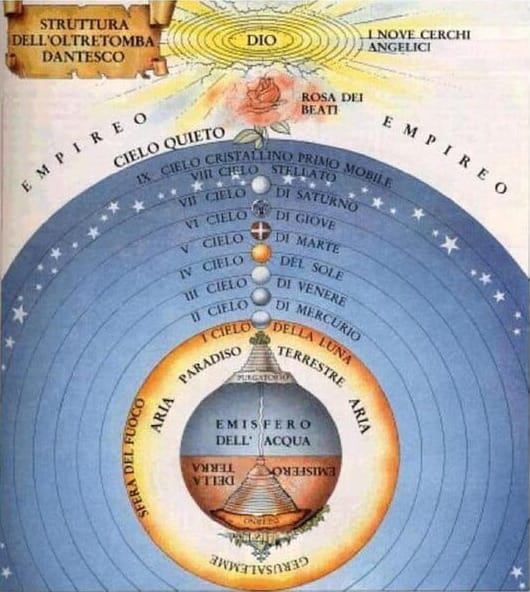

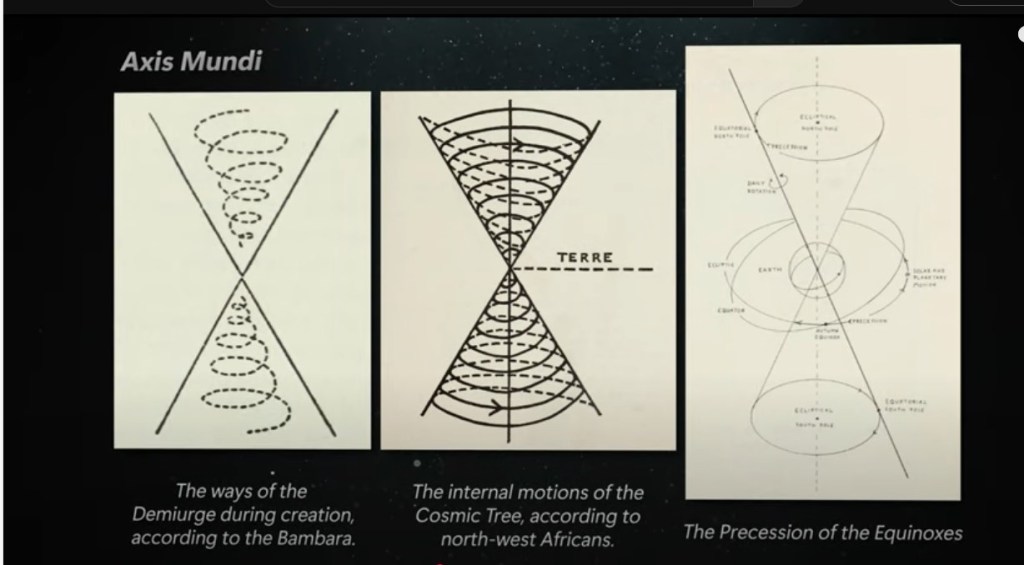

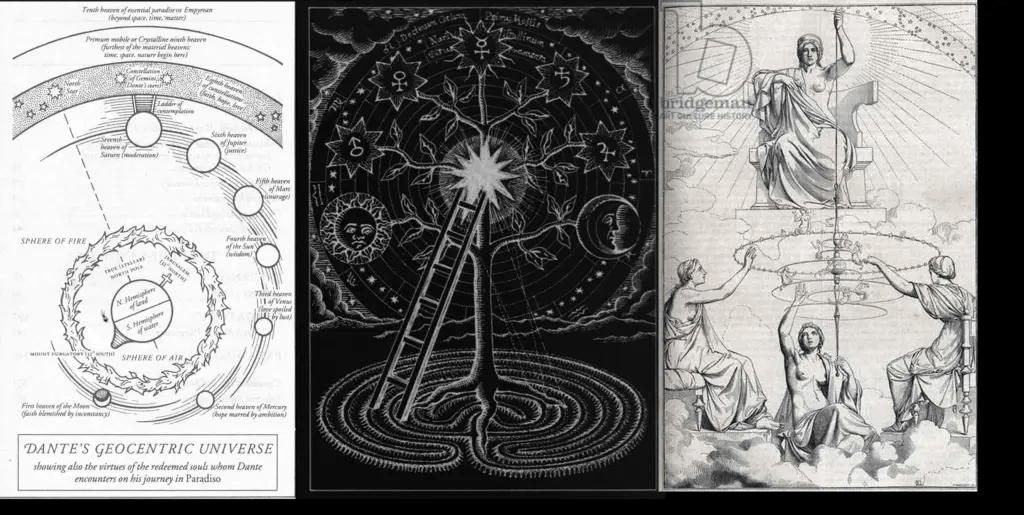

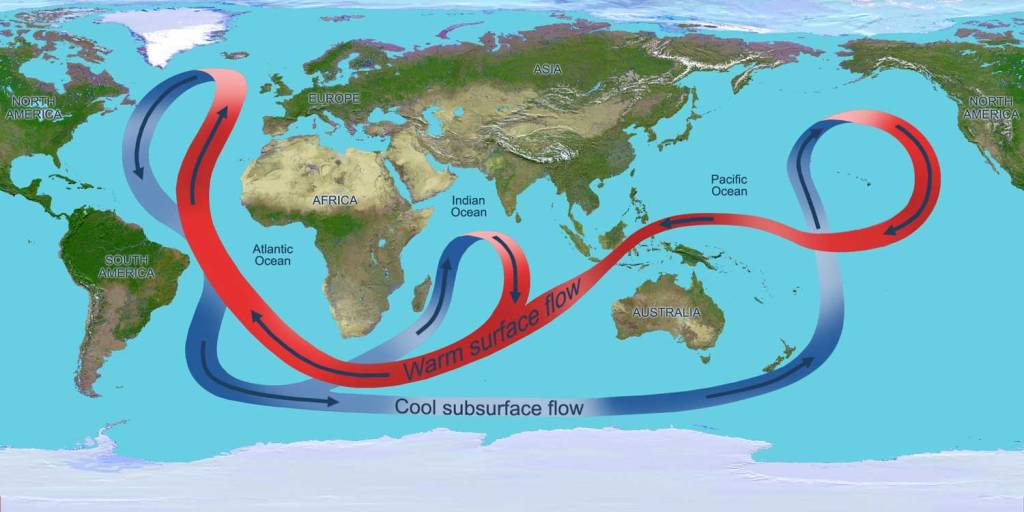

In contrast, properly disciplined imagination has the capacity to perceive God’s self-disclosure in all Three Books of creation. As Ibn ‘Arabî remarks, when God speaks—and he speaks because the Infinite Real cannot but display its qualities and characteristics—he voices three books, each of which is made up of signs/verses: the universe perceptible to the senses, the universe that can be apprehended by pure intellectual Perception, and – existing between them – an intermediate world, the world of Idea-Images, of archetypal figures, of subtile substances, of “immaterial matter”. The world of Imagination, of media.

The symbolic and mythic language of scripture, like the constantly shifting and never-repeated self-disclosures that are cosmos and soul, cannot be interpreted away with reason’s structures. What Corbin calls “creative imagination” (a term that does not have an exact equivalent in Ibn ‘Arabî’s vocabulary) must complement rational perception.

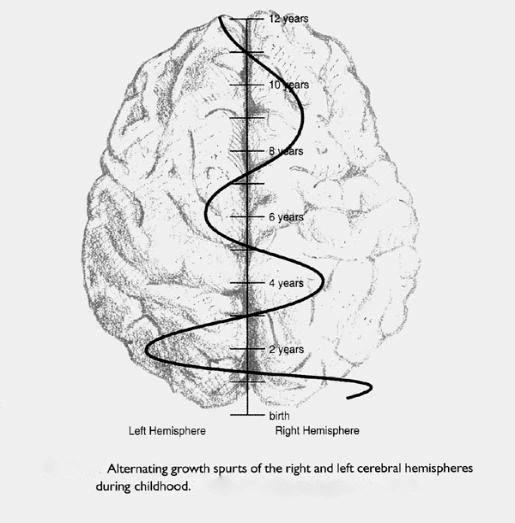

‘Aql or reason, a word that derives from the same root as ‘iqâl, fetter, can only delimit, define, and analyze. It perceives difference and distinction, and quickly grasps the divine transcendence and incomparability”. The rationalising, analytic left hemisphere does not understand the imaginative and holistic right hemisphere, which comprehends and contains it. “The natural man understandeth not the things of the Spirit of God: neither can he know them, because they are spiritually discerned” (1 Corinthians 2:14)

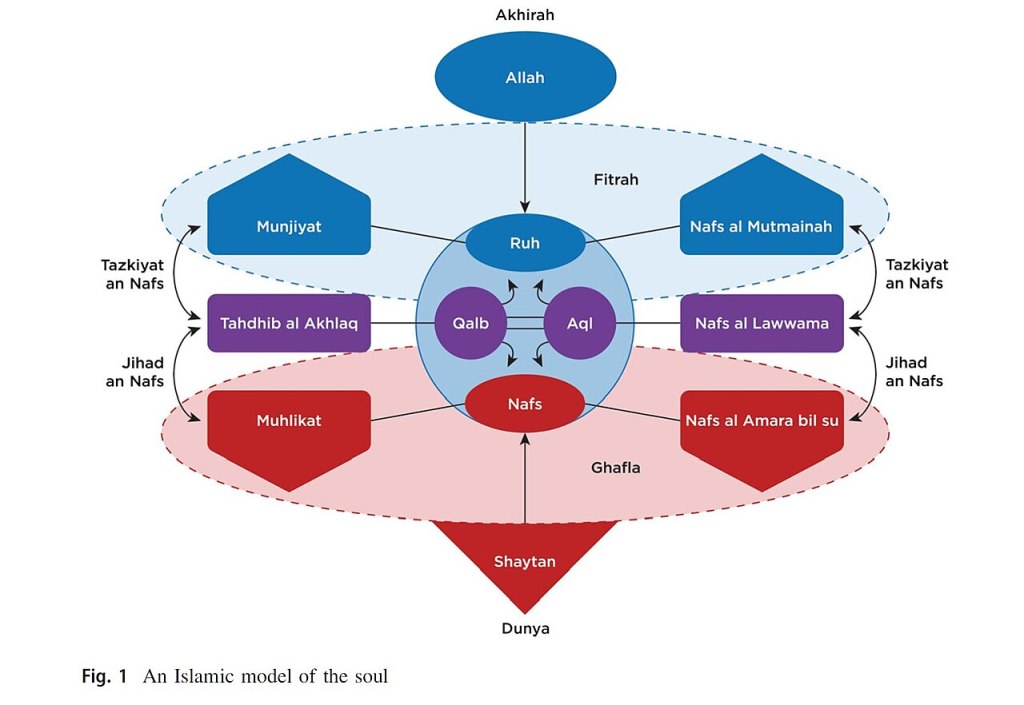

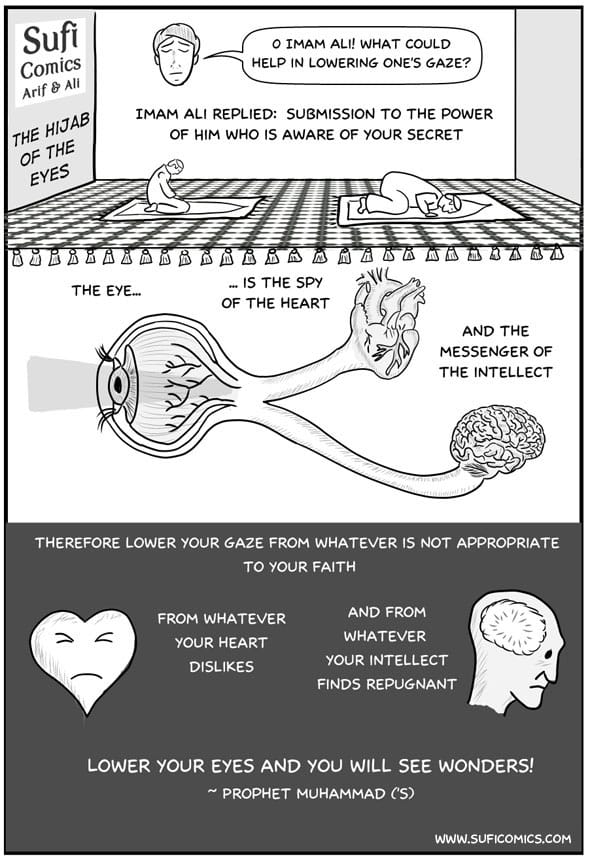

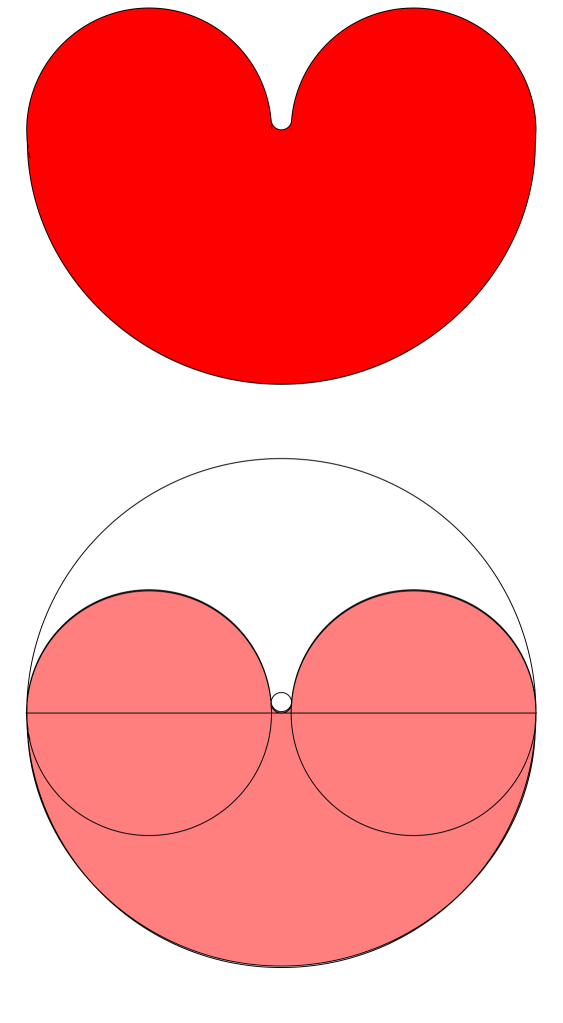

In Koranic terms, the locus of awareness and consciousness is the heart (qalb), a word that has the verbal sense of fluctuation and transmutation (taqallub). According to Ibn ‘Arabî, the heart has two eyes, reason and imagination, and the dominance of either distorts perception and awareness.

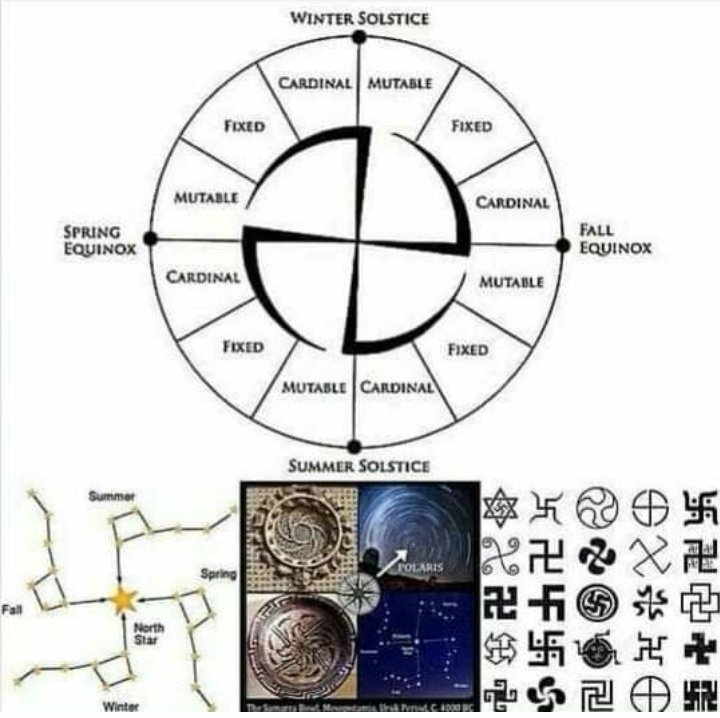

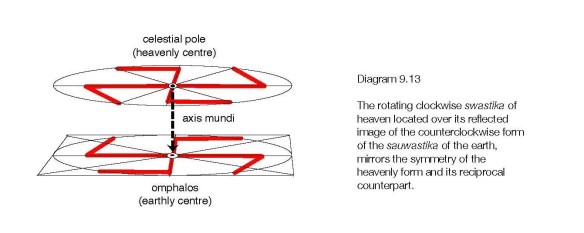

The rational path of philosophers and theologians needs to be complemented by the mystical intuition of the Sufis, the “unveiling” (kashf) that allows for imaginal—not “imaginary”—vision. The heart, which in itself is unitary consciousness, must become attuned to its own fluctuation, at one beat seeing God’s incomparability with the eye of reason, at the next seeing his similarity with the eye of imagination. Its two visions are prefigured in the two primary names of the Scripture, al-qur’ân, “that which brings together”, and al-furqân, “that which differentiates”.

These two demarcate the contours of ontology and epistemology. The first alludes to the unifying oneness of Being (perceived by imagination), and the second to the differentiating manyness of knowledge and discernment (perceived by reason). The Real, as Ibn ‘Arabî often says, is the One/the Many (al-wâhid al-kathîr), that is, One in Essence and many in names, the names being the principles of all multiplicity, limitation, and definition. In effect, with the eye of imagination, the heart sees Being present in all things, and with the eye of reason it discerns its transcendence and the diversity of the divine faces.

When Ibn ‘Arabî talks about imagination as one of the heart’s two eyes, he is using the language that philosophers established in speaking of the soul’s faculties. Like the philosophers, Ibn ‘Arabî sees the human soul as an unlimited potential and understands the goal of life to lie in the actualization of that potential. But he is more concerned with imagination’s ontological status, about which the early philosophers had little to say.

Here his use of khayâl accords with its everyday meaning, which is closer to image than imagination. It was employed to designate mirror images, shadows, scarecrows, and everything that appears in dreams and visions; in this sense it is synonymous with the term mithâl, which was often preferred by later authors. Ibn ‘Arabî stresses that an image brings together two sides and unites them as one; it is both the same as and different from the two.

A mirror image is both the mirror and the object that it reflects, or, it is neither the mirror nor the object. A dream is both the soul and what is seen, or, it is neither the soul nor what is seen. By nature images are/are not. In the eye of reason, a notion is either true or false. Imagination perceives notions as images and recognizes that they are simultaneously true and false, or neither true nor false. The implications for ontology become clear when we look at the three “worlds of imagination”.

- The Personal and Impersonal God by Harold Bloom

Why pray to the Stranger God? He is so alienated from our cosmological emptiness that he could never hear us. We might want to pray for him, but to whom? As for believing that he exists: we have no term for his wandering on the outer spaces, so existence does not apply. What matters most is necessarily either too far outside us or too far within us to be available, even if our readiness were all.

What is the use of gnosis, if it is so forbiddingly elitist? Since the alternatives are diseases of the will and of the intellect, why invoke the criterion of usefulness? Prayers are a more interesting literary form than creeds, but even the most impressive of prayers will not change us, let alone change God.

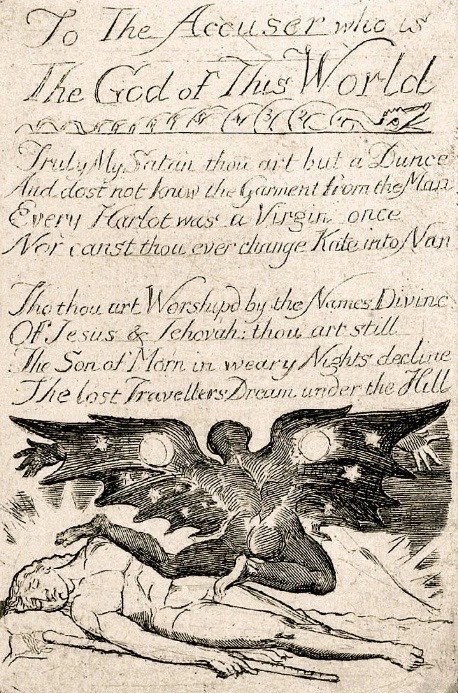

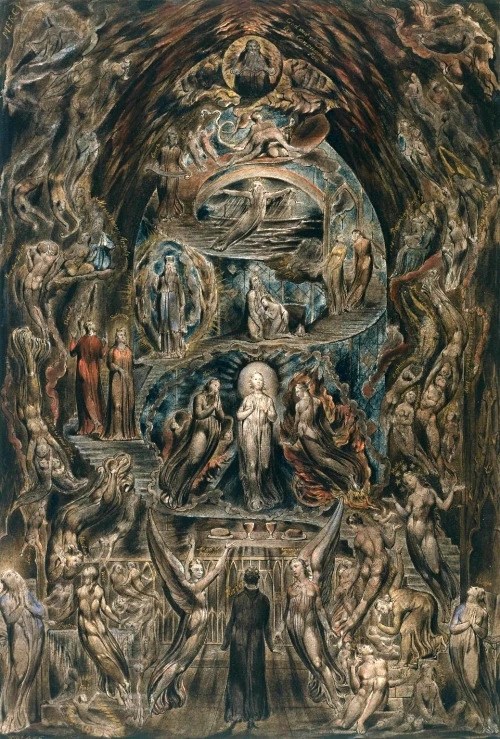

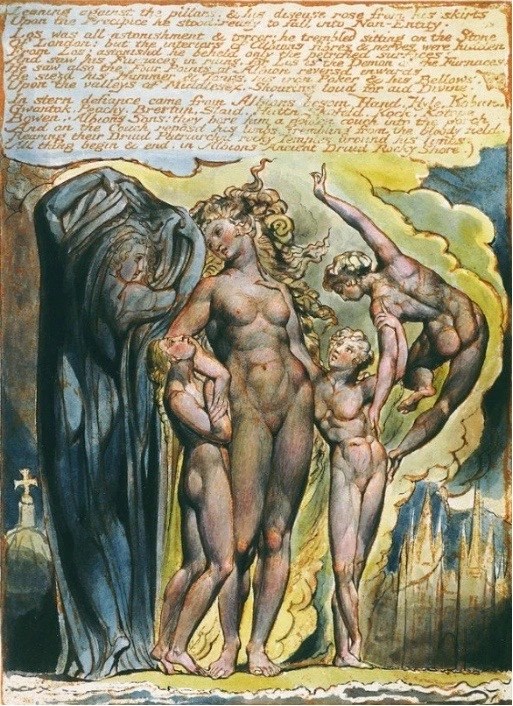

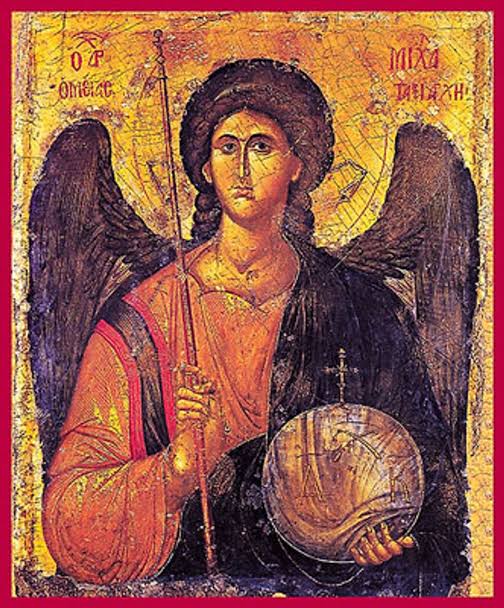

And nearly all prayers are directed anyway to the archons, the angels who made and marred this world, and whom we worship, William Blake warned, as Jesus and Jehovah, Divine Names misapplied to our prison warders. The Accusers who are the gods of this world have won all of the victories, and they will go on triumphing over us. History is always on their side, for they are history.

“the angels who made and marred this world, and whom we worship, William Blake warned, as Jesus and Jehovah, Divine Names misapplied to our prison warders”

The Nature of Imagination

Henry Corbin with Carl Jung, c. 1950

Here we shall not be dealing with imagination in the usual sense of the word: neither with fantasy, profane or otherwise, nor with the organ which produces imaginings identified with the unreal; nor shall we even be dealing exactly with what we look upon as the organ of aesthetic creation. We shall be speaking of an absolutely basic function, correlated with a universe peculiar to it, a universe endowed with a perfectly “objective” existence and perceived precisely through the Imagination.

Today, with the help of phenomenology, we are able to examine the way in which man experiences his relationship to the world without reducing the objective data of this experience to data of sense perception or limiting the field of true and meaningful knowledge to the mere operations of the rational understanding. Freed from an old impasse, we have learned to register and to make use of the intentions implicit in all the acts of consciousness or trans-consciousness.

To say that the Imagination (or love, or sympathy, or any other sentiment) induces knowledge, and knowledge of an “object” which is proper to it, no longer smacks of paradox. Still, once the full noetic value of the Imagination is admitted, it may be advisable to free the intentions of the Imagination from the parentheses in which a purely phenomenological interpretation encloses them, if we wish, without fear or misunderstanding, to relate the imaginative function to the view of the world proposed by the Spiritualists to whose company the present study invites us.

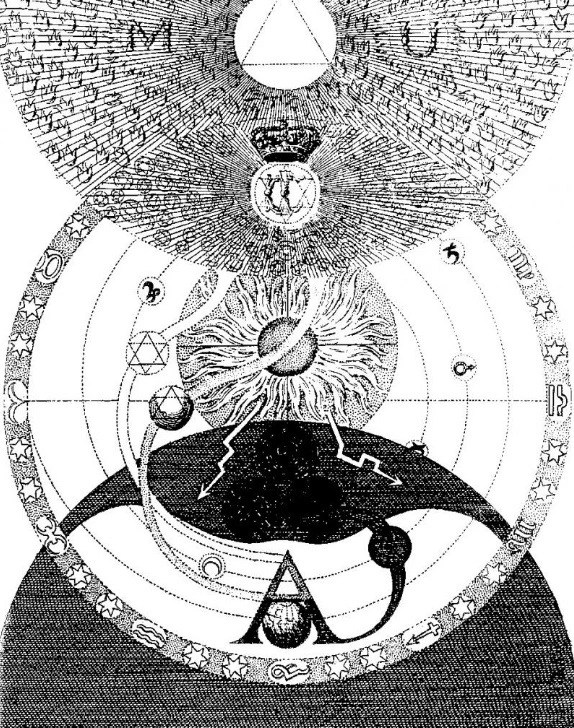

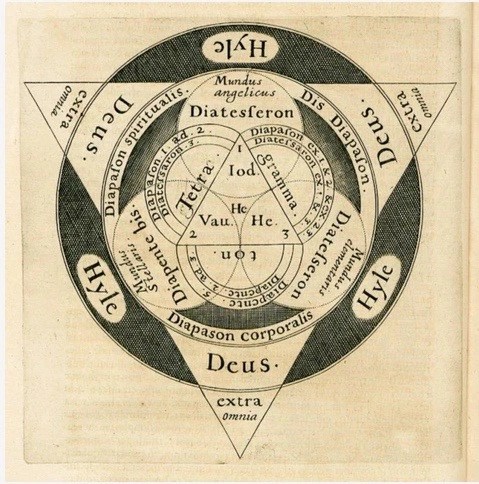

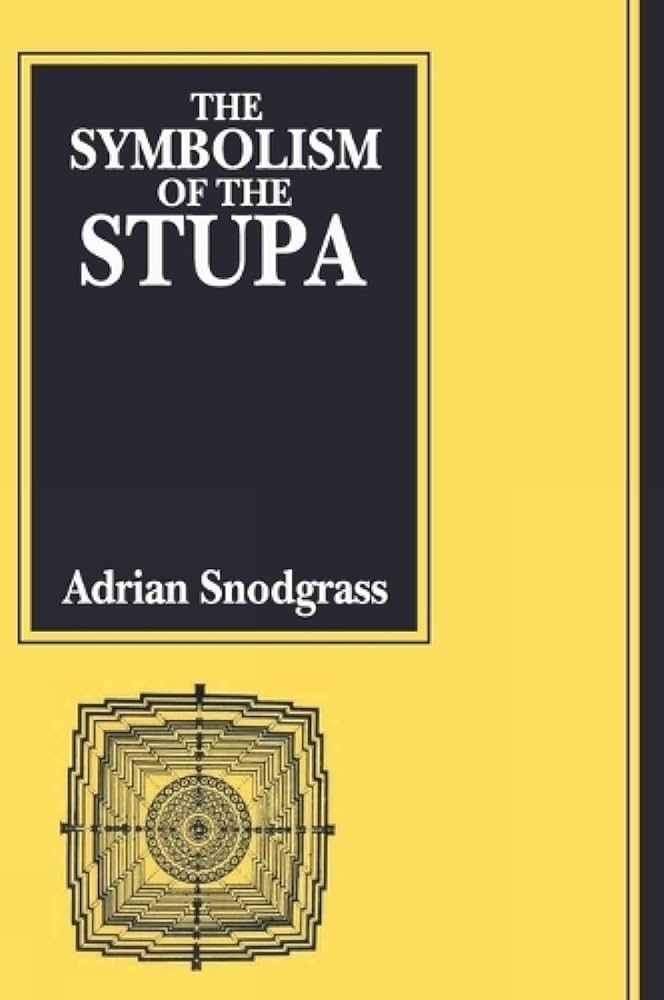

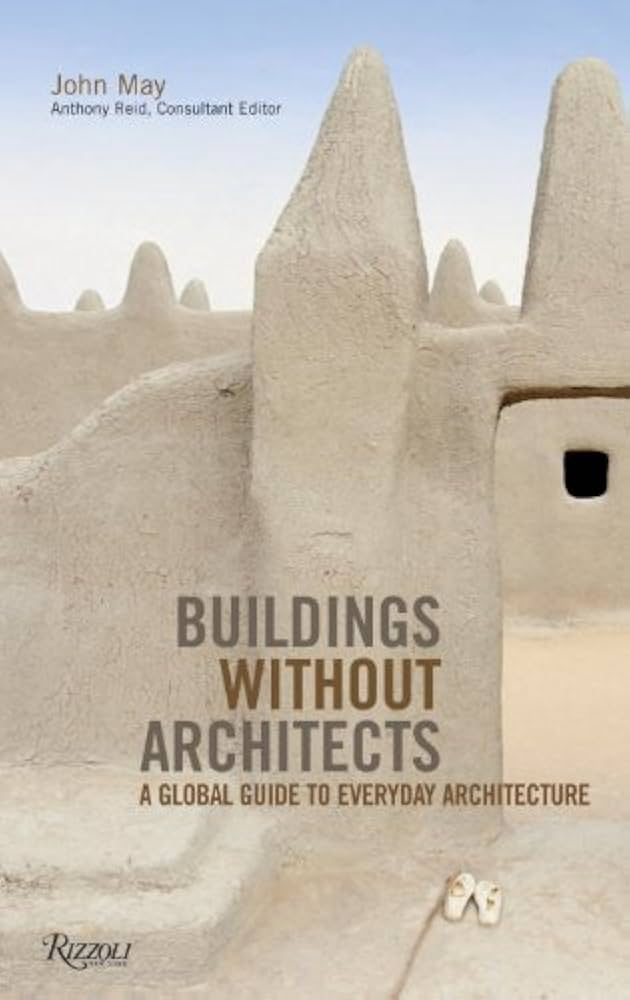

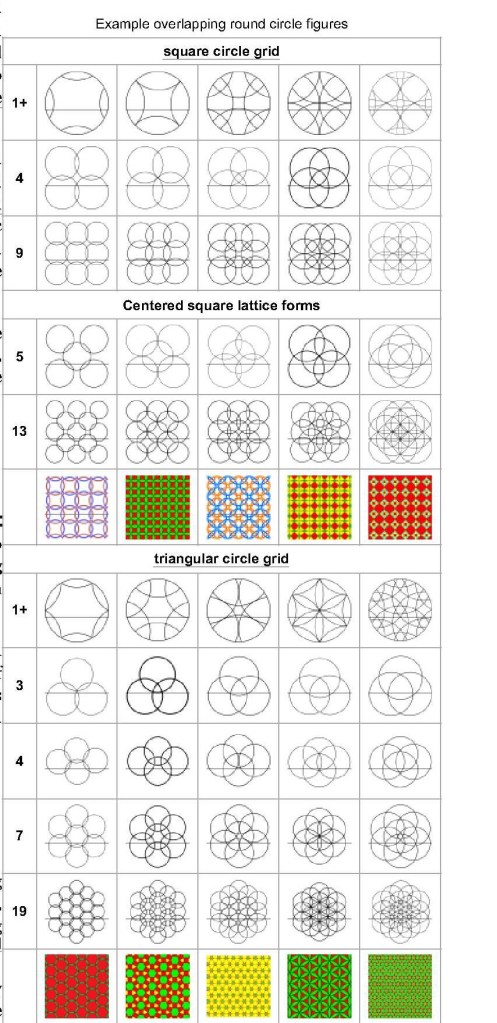

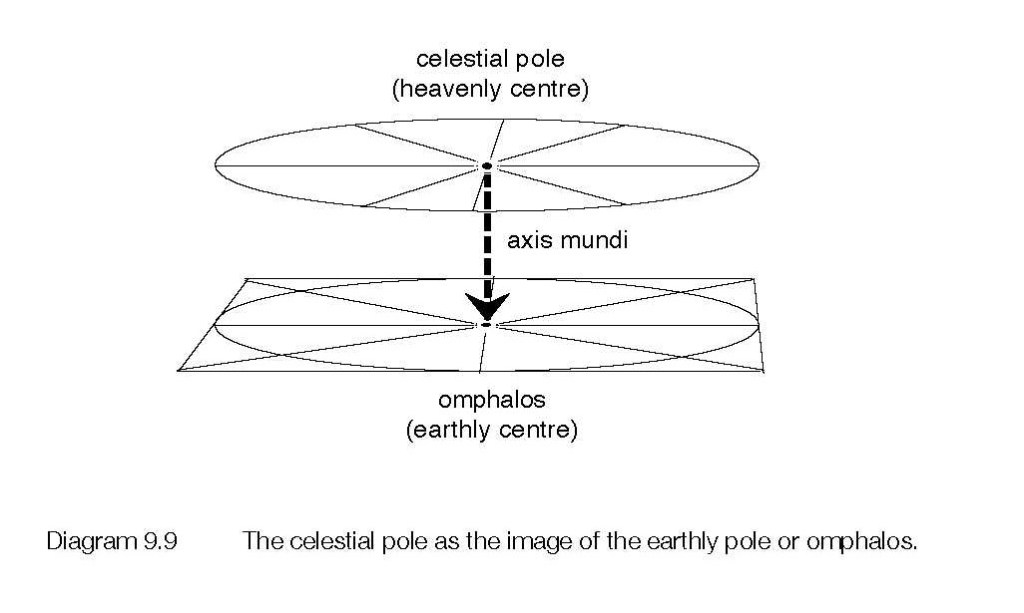

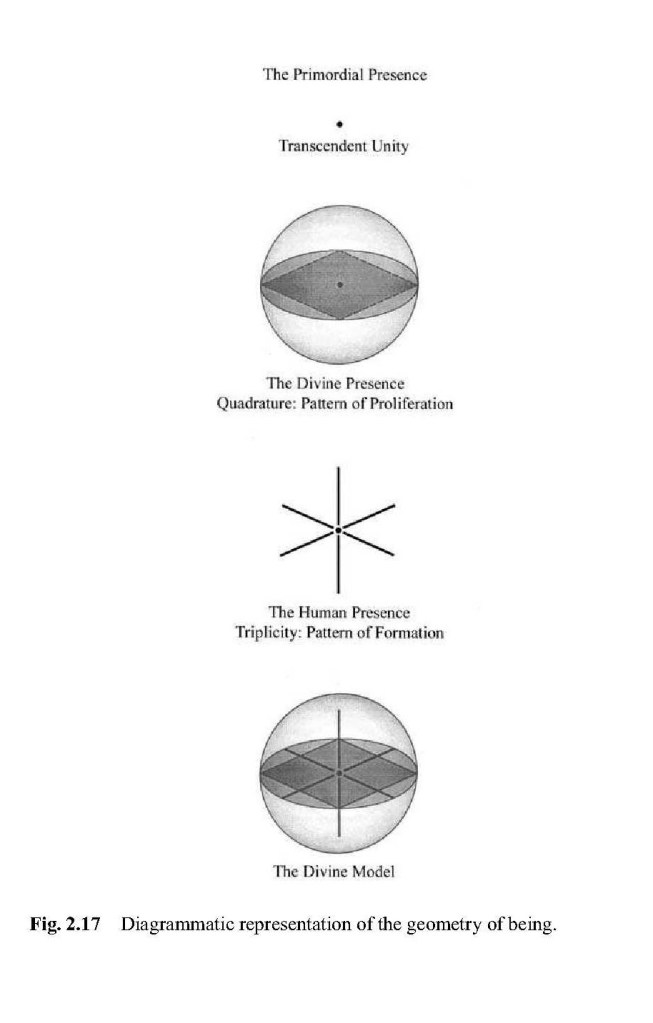

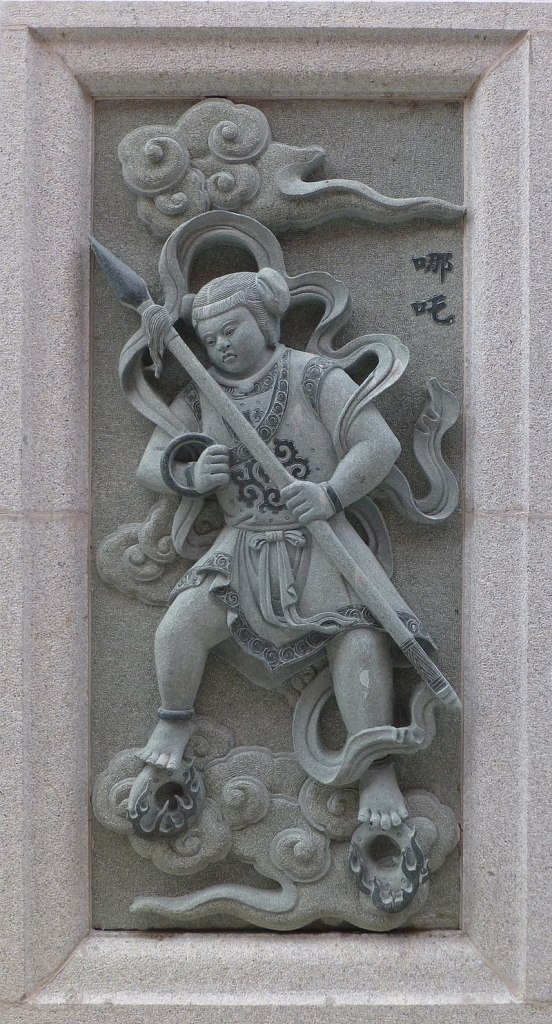

The Intermediary World of Archetypes, or ‘Images’

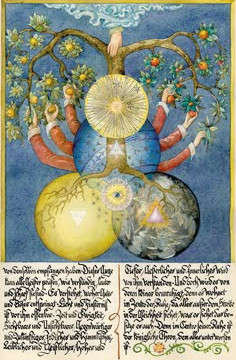

For them the world is “objectively” and actually threefold: between the universe that can be apprehended by pure intellectual perception (the universe of the Cherubic Intelligences) and the universe perceptible to the senses, there is an intermediate world, the world of Idea-Images, of archetypal figures, of subtile substances, of “immaterial matter.” This world is as real and objective, as consistent and subsistent as the intelligible and sensible world; it is an intermediate universe “where the spiritual takes body and the body becomes spiritual,” a world consisting of real matter and real extension, though by comparison to sensible, corruptible matter these are subtile and immaterial.

The organ of this universe is the active Imagination; it is the place of theophanic visions, the scene on which visionary events and symbolic histories appear in their true reality.

We shall try to show in what sense this Imagination is creative: because it is essentially the active Imagination and because its activity defines it essentially as a theophanic Imagination. It assumes an unparalleled function, so out of keeping with the inoffensive or pejorative view commonly taken of the “imagination,” that we might have preferred to designate this Imagination by a neologism and have occasionally employed the term Imaginatrix.

Avicennism identifies it with the Holy Spirit, that is, with the Angel Gabriel as the Angel of Knowledge and of Revelation.

Allegory vs. Imagination

At this point we must recapitulate the distinction, fundamental for us, between allegory and symbol; allegory is a rational operation, implying no transition either to a new plane of being or to a new depth of consciousness; it is a figuration, at an identical level of consciousness, of what might very well be known in a different way.

The symbol announces a plane of consciousness distinct from that of rational evidence; it is the “cipher” of a mystery, the only means of saying something that cannot be apprehended in any other way; a symbol is never “explained” once and for all, but must be deciphered over and over again, just as a musical score is never deciphered once and for all, but calls for ever new execution.

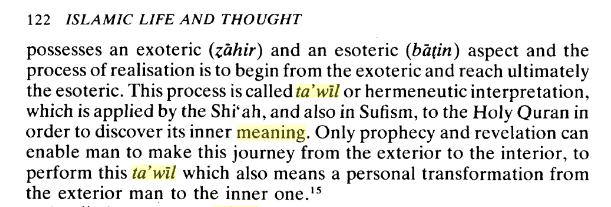

Active Imagination and the Burning Bush

The Avicennan angelology provides the foundation of the intermediate world of pure Imagination; it made possible the prophetic psychology on which rested the spirit of symbolic exegesis, the spiritual understanding of Revelations, in short, the ta’wll which was equally fundamental to Sufism and to Shi’ism (etymologically the “carrying back” of a thing to its principle, of a symbol to what it symbolizes). The ta’wll presupposes a flowering of symbols and hence the active Imagination, the organ which at once produces symbols and apprehends them.

The conviction that to everything that is apparent, literal, external, exoteric (zahir) there corresponds something hidden, spiritual, internal, esoteric (batin) is the scriptural principle which is at the very foundation of Shi’ism as a religious phenomenon. It is the central postulate of esoterism and of esoteric hermeneutics (ta’wil).

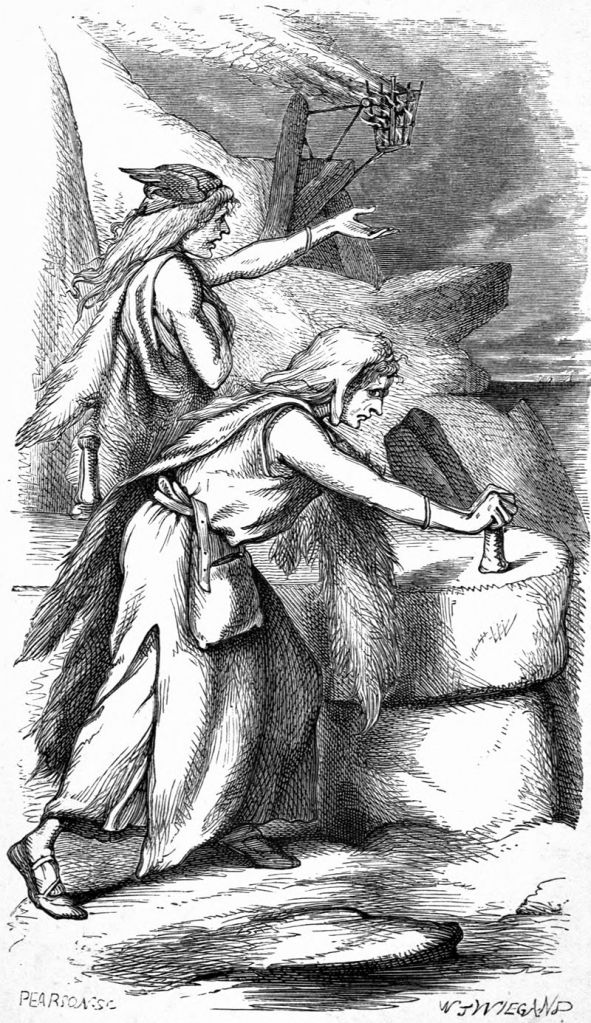

The active Imagination guides, anticipates, moulds sense perception; that is why it transmutes sensory data into symbols. The Burning Bush is only a brushwood fire if it is merely perceived by the sensory organs. In order that Moses may perceive the Burning Bush and hear the Voice calling him “from the right side of the valley”- in short, in order that there may be a theophany – an organ of trans-sensory perception is needed.

Since the Imagination is the organ of theophanic perception, it is also the organ of prophetic hermeneutics, for it is the imagination which is at all times capable of transmuting sensory data into symbols and external events into symbolic histories.

Our meaning is expressed in the following anecdote which we owe to Semnani, the great Iranian Sufi: Jesus was sleeping with a brick for pillow. The accursed demon came and stopped at his bedside. When Jesus sensed that the accursed one was there, he woke up and said: Why hast thou come to me, accursed one? – I have come to get my things. – And what things of thine are there here? – This brick that thou restest thine head on. – Then Jesus (Ruh Allah, Spiritus Dei) seized the brick and flung it in his face.

Naming God

Thus the true name of the Divinity, the name which expresses His hidden depths, is not the Infinite and All-Powerful of our rational theodicies. Nothing can better bear witness to the feeling for a “pathetic God,” which is no less authentic than that disclosed (as we have seen above) by a phenomenology of prophetic religion.

Here we are at the heart of a mystical gnosis, and that is why we have refused to let ourselves be restricted to the above-mentioned opposition. For Ismailian Gnosis, the supreme Godhead cannot be known or even named as “God”; Al-Lah is a name which indeed is given to the created being, the Most-Near and sacrosanct Archangel, the Protokistos or Archangel-Logos. This Name then expresses sadness, nostalgia aspiring eternally to know the Principle which eternally initiates it: the nostalgia of the revealed God (i.e., revealed for man) yearning to be once more beyond His revealed being.

This mediating faculty is the active or creative Imagination which Ibn ‘Arabî designates as “Presence” or “imaginative Dignity” (Hadrat khayallya). Perhaps we are in need of a neologism to safeguard the meaning of this “Dignity ” and to avoid confusion with the current acceptance of the word “imaginative.” We might speak of an Imaginatrix.

Here the spiritual aspect, the Spirit, must manifest itself in a physical form; this Form may be a sensible figure which the Imagination transmutes into a theophanic figure, or else it may be an “apparitional figure” perceptible to the unaided imagination without the mediation of a sensible form in the instant of contemplation.

Thus the experience of mystic love, which is a conjunction (“conspiration”) of the spiritual and the physical, implies that imaginative Energy, or creative Imagination, the theory of which plays so large a part in the visionary experience of Ibn ‘Arabî. As organ of the transmutation of the sensible, it has the power to manifest the “angelic function of beings.” In so doing, it effects a twofold movement; on the one hand it causes invisible spiritual realities to descend to the reality of the Image (but no further, for to our authors the lmaginalia are the maximum of “material” condensation compatible with spiritual realities); and it also effects the only possible form of assimilation (taskbrk) between Creator and creature.

And on the other hand the image itself, though distinct from the sensible world, is not alien to it, for the Imagination transmutes the sensible world by raising it up to its own subtile and incorruptible modality. This twofold movement, which is at the same time a descent of the divine and an assumption of the sensible, corresponds to what Ibn ‘Arabî elsewhere designates etymologically as a “condescendence” (munazala). The Imagination is the scene of the encounter whereby the supersensory-divine and the sensible “descend” at one and the same “abode.”

Thus it is the Active Imagination which places the invisible and the visible, the spiritual and the physical in sympathy. It is the Active Imagination that makes it possible, as our shaikh declares, “to love a being of the sensible world, in whom we love the manifestation of the divine Beloved; for we spiritualize this being by raising him (from sensible form) to incorruptible Image (that is, to the rank of a theophanic Image), by investing him with a beauty higher than that which was his, and clothing him in a presence such that he can neither lose it nor cast it off, so that the mystic never ceases to be united with the Beloved.”

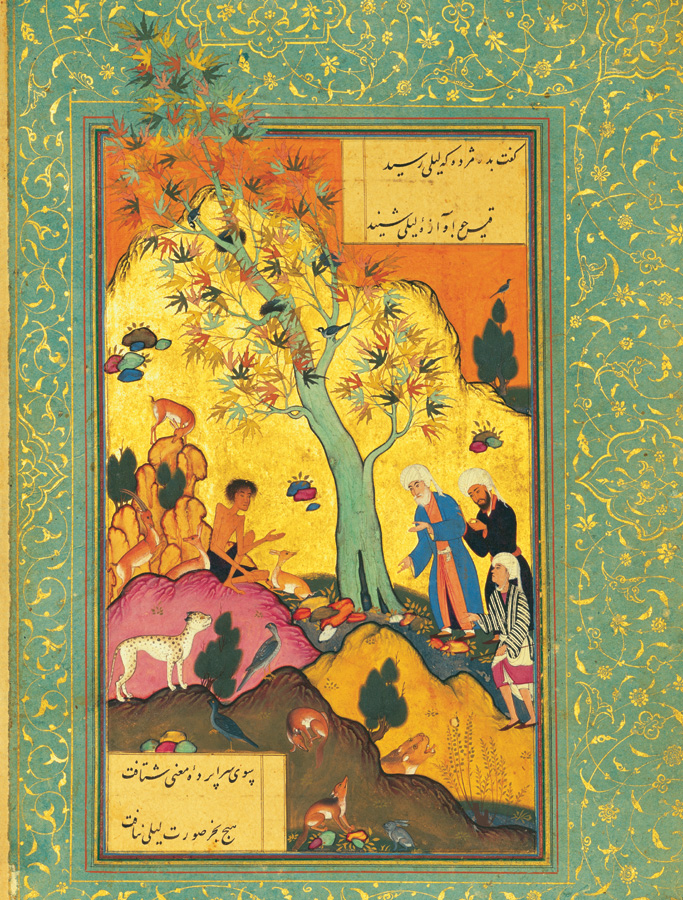

For this reason the degree of spiritual experience depends on the degree of reality invested in the Image, and conversely, it is in this Image that the mystic contemplates in actu the full perfection of the Beloved and that he experiences His presence within himself. Without this “imaginative union” (ttisiil jl’l-ltkayal), without the “transfiguration” it brings about, physical union is a mere delusion, a cause or symptom of mental derangement. Pure “imaginative contemplation” (muskakadat ltkayallya), on the other hand, can attain such intensity that any material and sensible presence would only draw it down. Such was the famous case of Majnun, and this, says Ibn ‘Arabî, is the most subtile phenomenon of love.

Indeed this phenomenon presupposes that the fedele d’amore has understood that the Image is not outside him, but within his being; better still, it is his very being, the form of the divine Name which he himself brought with him in coming into being. And the circle of the dialectic of love closes on this fundamental experience: “Love is closer to the lover than is his jugular vein.” So excessive is this nearness that it acts at first as a veil. That is why the inexperienced novice, though dominated by the Image which invests his whole inner being, goes looking for it outside of himself, in a desperate search from form to form of the sensible world, until he returns to the sanctuary of his soul and perceives that the real Beloved is deep within his own being; and, from that moment on, he seeks the Beloved only through the Beloved.

In this Quest as in this Return, the active subject within him remains the inner image of unreal Beauty, a vestige of the transcendent or celestial counterpart of his being: it is that image which causes him to recognize every concrete figure that resembles it, because even before he is aware of it, the Image has invested him with its theophanic function. That is why, as Ibn ‘Arabî puts it, it is equally true to say that the Beloved is in him and not in him; that his heart is in the beloved being or that the beloved being is in his heart.

This reversibility merely expresses the experience of the “secret of divine suzerainty” (sirr al-rubublya), that secret which is “thou,” so that the divine service of the fedele d’amore consists in his devotio sympathetica, which is to say, the “substantiation” by his whole being of the theophanic investiture which he confers upon a visible form. That is why the quality and the fidelity of the mystic lover are contingent on his “imaginative power,” for as Ibn ‘Arabî says: “The divine Lover is spirit without body; the purely physical lover is body without spirit; the spiritual lover (that is, the mystic lover) possesses spirit and body.”

Image and Magic

“The notion of the imagination, magical intermediary between thought and being, incarnation of thought in image and presence of the image in being, is a conception of the utmost importance, which plays a leading role in the philosophy of the Renaissance and which we meet with again in the philosophy of Romanticism” (Alexandre Koyré). This observation, taken from one of our foremost interpreters of the doctrines of Boehme and Paracelsus, provides the best possible introduction to the notion of the Imagination as the magical production of an image, the very type and model of magical action, or of all action as such, but especially of creative action; and, on the other hand, the notion of the image as a body (a magical body, a mental body), in which are incarnated the thought and will of the soul.

The Imagination as a creative magical potency which, giving birth to the sensible world, produces the Spirit in forms and colors; the world as Magia divina “imagined” by the Godhead, that is the ancient doctrine, typified in the juxtaposition of the words Imago and Magia, which Novalis rediscovered through Fichte.

Accordingly, everything will depend on the degree of reality that we impute to this imagined universe and by that same token on the real power we impute to the Imagination that imagines it; but both questions depend in turn on the idea that we form of creation and the creative act.

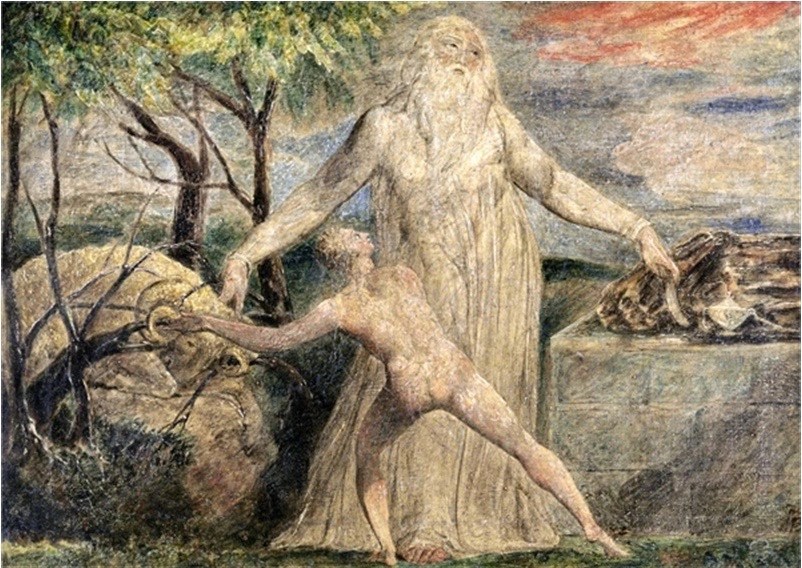

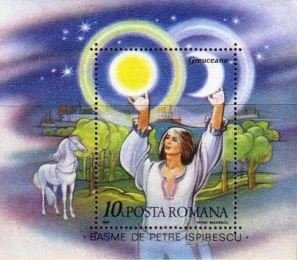

Adam’s Dream: The Creation of This World

But between the theosophy of Ibn ‘Arabî and that of a theosophist of the Renaissance or of Jacob Boehme’s school, there are correspondences sufficiently striking to motivate the comparative studies outlining the respective situation of esoterism in Islam and in Christianity.

On both sides we encounter the idea that the Godhead possesses the power of Imagination, and that by imagining the universe God created it; that He drew this universe from within Himself, from the eternal virtualities and potencies of His own being; that there exists between the universe of pure spirit and the sensible world an intermediate world which is the idea of “Idea Images” as the Sufis put it, the world of “supersensory sensibility,” of the subtile magical body, “the world in which spirits are materialized and bodies spiritualized”; that this is the world over which the Imagination holds sway; that in it the Imagination produces effects so real that they can “mould” the imagining subject, and that the Imagination “casts” man in the form (the mental body) that he has imagined.

In general we note that the degree of reality thus imputed to the Image and the creativity imputed to the Imagination correspond to a notion of creation unrelated to the official theological doctrine, the doctrine of the creatio ex nihilo, which has become so much a part of our habits that we tend to regard it as the only authentic idea of creation. We might even go so far as to ask whether there is not a necessary correlation between this idea of a creatio ex nihilo and the degradation of the ontologically creative Imagination and whether, in consequence, the degeneration of the Imagination into a fantasy productive only of the imaginary and the unreal is not the hallmark of our laicized world for which the foundations were laid by the preceding religious world, which precisely was dominated by this characteristic idea of the Creation.

The initial idea of Ibn ‘Arabi’s mystic theosophy and of all related theosophies is that the Creation is essentially a theophany (tajalll). As such, creation is an act of the divine imaginative power: this divine creative imagination is essentially a theophanic Imagination. The Active Imagination in the gnostic is likewise a theophanic Imagination; the beings it “creates” subsist with an independent existence sui generis in the intermediate world which pertains to this mode of existence.

The God whom it “creates,” far from being an unreal product of our fantasy, is also a theophany, for man’s Active Imagination is merely the organ of the absolute theophanic Imagination (takkayyul mutlaq). Prayer is a theophany par excellence; as such, it is “creative”; but the God to whom it is addressed because it “creates” Him is precisely the God who reveals Himself to Prayer in this Creation, and this Creation, at this moment, is one among the theophanies whose real Subject is the Godhead revealing Himself to Himself.

Image as Veil

“the Appearance (and transparency) beneath which He manifests and reveals Himself first of all to Himself”

The Creature-Creator, the Creator who does not produce His creation outside Him, but in a manner of speaking clothes Himself in it as the Appearance (and transparency) beneath which He manifests and reveals Himself first of all to Himself, is referred to by several other names, such as the “imagined God,” that is, the God “manifested ” by the theophanic Imagination (al-Haqq al-mutakzayyal), the “God created in the faiths” (al-Haqq al-makluq fi’l-i’tiqadat).

To the initial act of the Creator imagining the world corresponds the creature imagining his world, imagining the worlds, his God, his symbols. Or rather, these are the phases, the recurrences of one and the same eternal process: Imagination effected in an Imagination (takhayyul fl takhayyul), an Imagination which is recurrent just as – and because – the Creation itself is recurrent. The same theophanic Imagination of the Creator who has revealed the worlds, renews the Creation from moment to moment in the human being whom He has revealed as His perfect image and who, in the mirror that this Image is, shows himself Him whose image he is.

That is why man’s Active Imagination cannot be a vain fiction, since it is this same theophanic Imagination which, in and by the human being, continues to reveal what it showed itself by first imagining it. Thus creation signifies nothing less than the Manifestation (zuhur) of the hidden (batin).

The Twofold Dimension of Beings

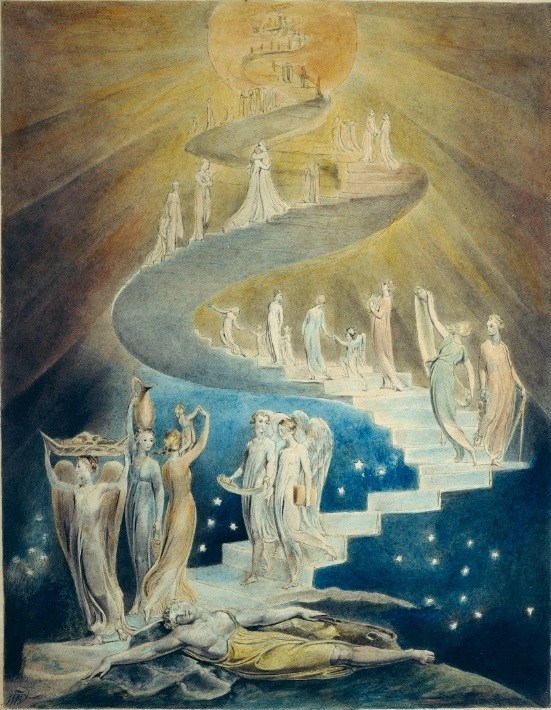

The initial imaginative operation is to typify (ta’wil) the immaterial and spiritual realities in external or sensuous forms, which then become “ciphers” for what they manifest. After that the Imagination remains the motive force of the ta’wll which is the continuous ascent of the soul.

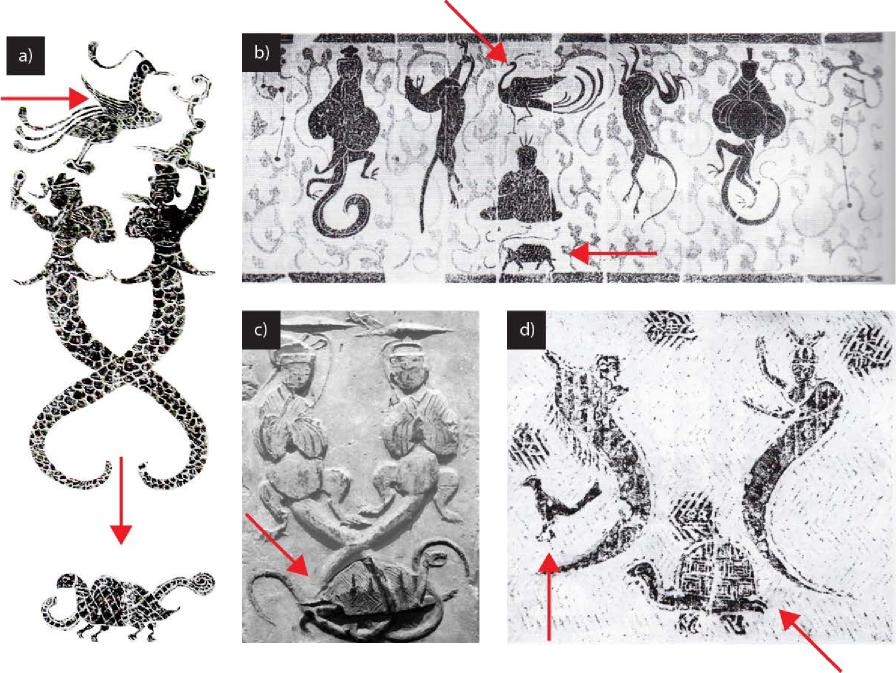

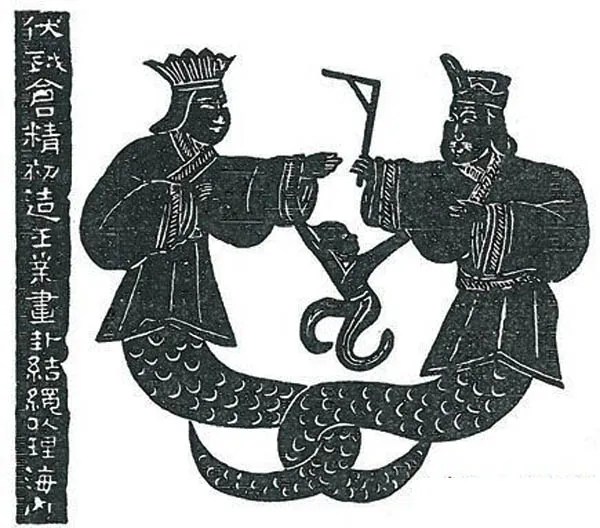

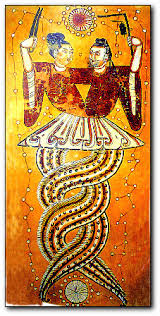

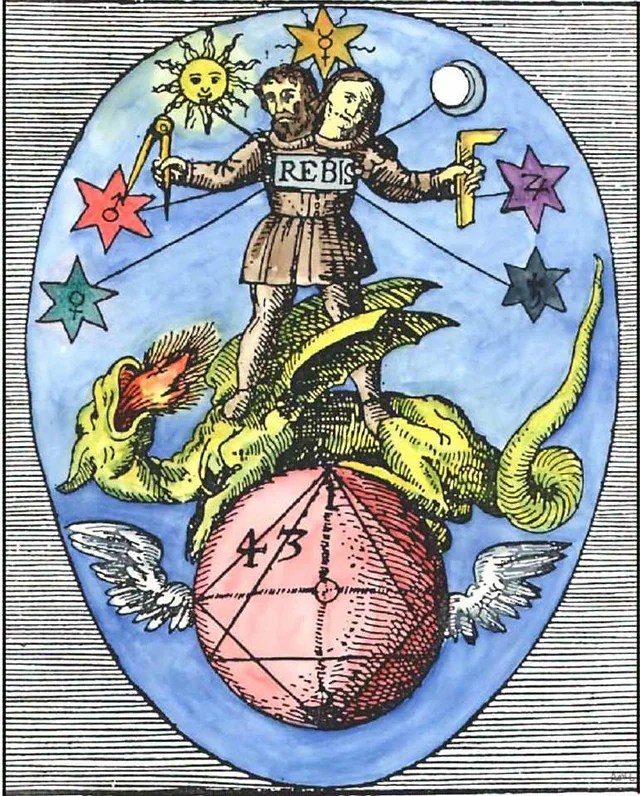

“the mysterium coniunctionis which unites the two terms”

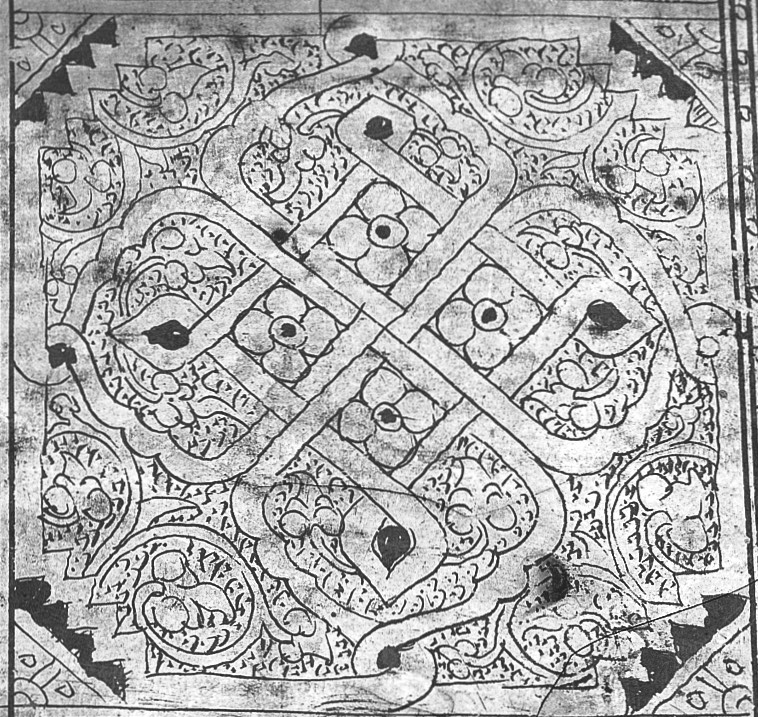

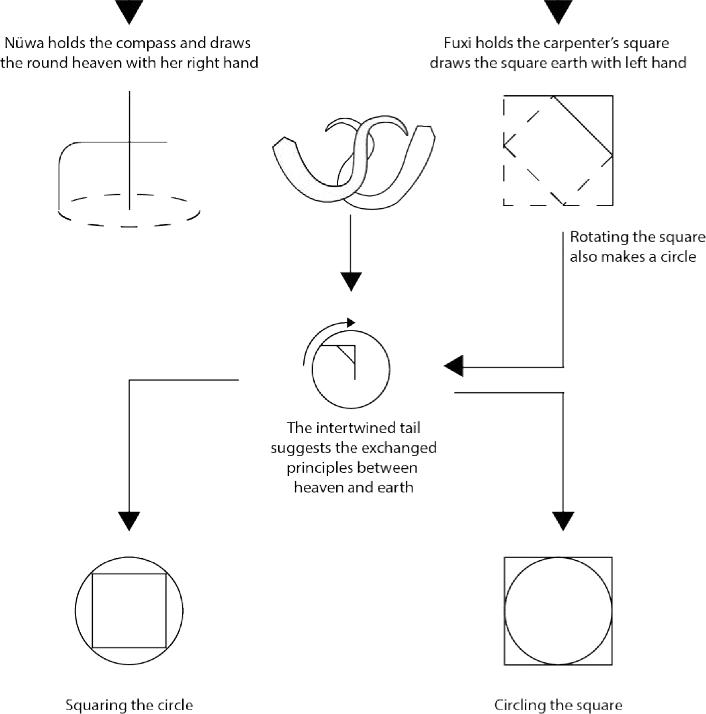

In short, because there is Imagination, there is ta’wll; because there is ta’wll, there is symbolism; and because there is symbolism, beings have two dimensions. This apperception reappears in all the pairs of terms that characterize the theosophy of Ibn ‘Arabî: Creator and Creature (Haqq and Khalq}, divinity and humanity (lahut and nasut), Lord and vassal (Rabb and ‘Abd).

Each pair of terms typifies a union for which we have suggested the term unio sympathetica. The union of the two terms of each pair constitutes a coincidentia oppositorum a simultaneity not of contradictories but of complementary opposites, and we have seen above that it is the specific function of the Active Imagination to effect this union which, according to the great Sufi Abu Sarid al-Kharrllz, defines our knowledge of the Godhead. But the essential here is that the mysterium coniunctionis which unites the two terms is a theophanic union (seen from the standpoint of the Creator) or a theopathic union (seen from the standpoint of the creature); in no event is it a “hypostatic union.”

The organ which establishes and perceives this coincidentia oppositorum, this simultaneity of complementaries determining the twofold dimension of beings, is man’s Active Imagination, which we may term creative insofar as it is, like Creation itself, theophanic.

On this point I awaken you to a sublime secret, from which a number of divine secrets are to be learned, for example, the secret of destiny and the secret of divine knowledge, and the fact that these are one and the same science by which the Creator and the Creature are known. These ideas are strictly related: When you create, it is not you who create, and that is why your creation is true. It is true because each creature has a twofold dimension: the Creator-creature typifies the coincidentia oppositorum.

The Science of the Imagination

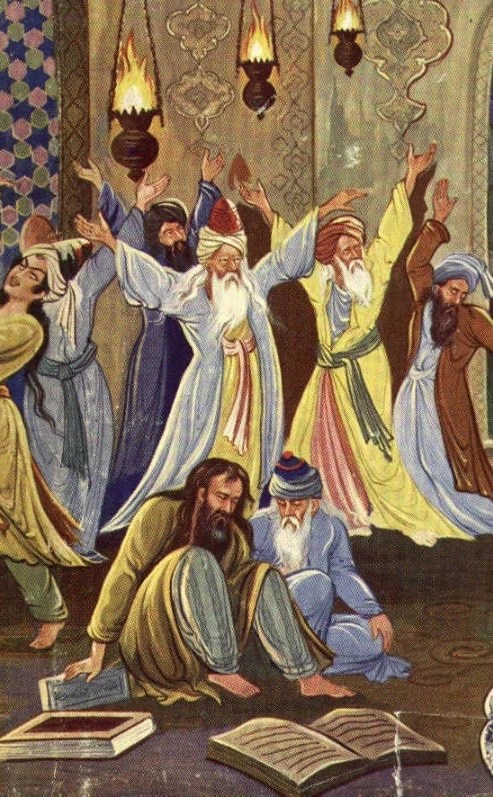

In a chapter of his great book, the Spiritual Conquests (or Revelations) of Mecca, Ibn ‘Arabî outlines a “science of the Imagination” (‘ilm al-khayal) and provides a schema of the themes involved in such a science. The organ of Prayer is the heart, the psycho-spiritual organ, with its concentration of energy, its himma. The role of prayer is shared between God and man, because Creation like theophany is shared between Him who shows Himself (mutajalll) and him to whom it is shown (mutajalla lahu); prayer itself is a moment in, a recurrence par excellence of, Creation (tajdld al-khalq).

We witness and participate in an entire ceremonial of meditation, a psalmody in two alternating voices, one human the other divine; and this psalmody perpetually reconstitutes, recreates (lrhalq jadld!) the solidarity and interdependence of the Creator and His creature; in each instant the act of primordial theophany is renewed in this psalmody of the Creator and the creature. This will enable us to understand the homologations that the ritual gestures of Prayer can obtain, to understand that Prayer is a “creator” of vision, and to understand how, because it is a creator of vision, it is simultaneously Prayer of God and Prayer of man. Then we shall gain an intimation of who and of what nature is the “Form of God,” when it shows itself to the mystic celebrating this inward liturgy.

Understood and experienced in this way, Prayer, because it is a muniljat, an intimate dialogue, implies at its apogee a mental theophany, capable of different degrees; but if it is not unsuccessful, it must open out into contemplative vision.

“Once, the young artist George Richmond, finding his invention flag during a whole fortnight, went to Blake, as was his wont, for some advice or comfort. He found him sitting at tea with his wife. He related his distress; how he felt deserted by the power of invention. To his astonishment, Blake turned to his wife suddenly and said : ‘It is just so with us, is it not, for weeks together, when the visions forsake us? What do we do then, Kate?’ ‘We kneel down and pray, Mr. Blake’.” (Gilchrist, Life of Blake)

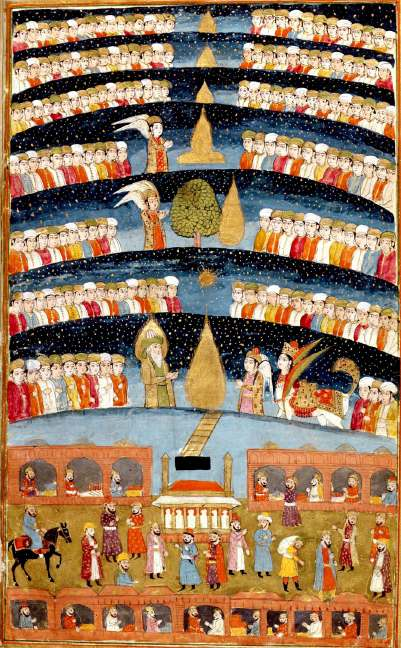

Here then is the manner in which Ibn ‘Arabî comments on the phases of a divine service that is a dialogue, an intimate dialogue which takes as its “psalm” and foundation the recitation of the Fatiha. He distinguishes three successive moments which correspond to the phases of what we may call his “method of prayer” and provide us with a good indication of how he put his spirituality into practice. First, the faithful must place himself in the company of his God and “converse” with Him. In an intermediate moment the orant, the faithful in prayer, must imagine (takhayyul) his God as present in his Qibla, that is, facing him. Finally, in a third moment, the faithful must attain to intuitive vision (shuhud) or visualization (ru’ya), contemplating his God in the subtile center which is the heart, and simultaneously hear the divine voice vibrating in all manifest things, so much so that he hears nothing else.

This is illustrated by the following distich of a Sufi: “When He shows Himself to me, my whole being is vision: when he speaks to me in secret, my whole being is hearing.” Here we encounter the practical meaning of the tradition which declares: “The entire Koran is a symbolic, allusive (ramz) story, between the Lover and the Beloved, and no one except the two of them understands the truth or reality of its intention.” Clearly, the entire “science of the heart” and all the creativity of the heart are needed to set in motion the ta’wll, the mystic interpretation which makes it possible to read and to practice the Koran as though it were a variant of the Song of Songs.

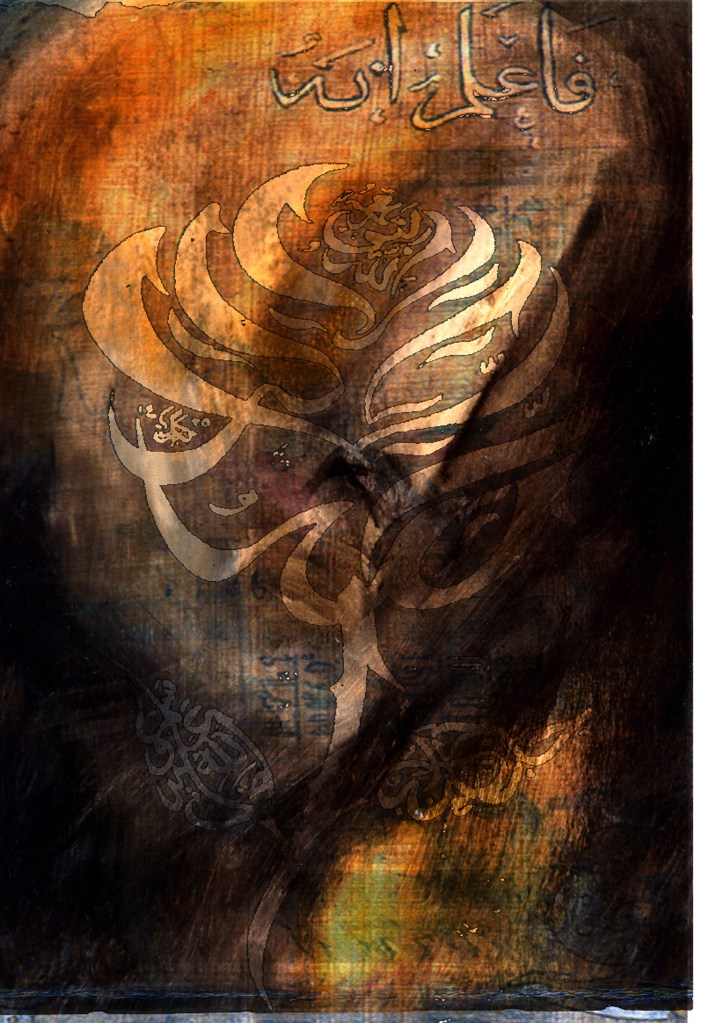

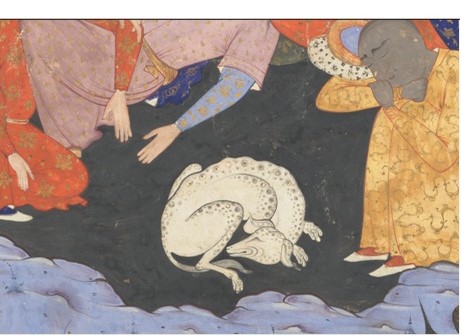

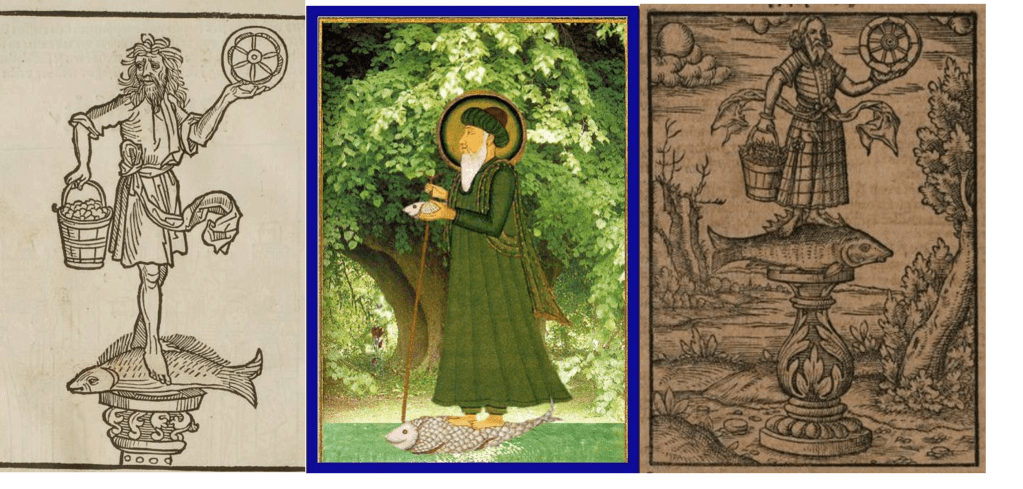

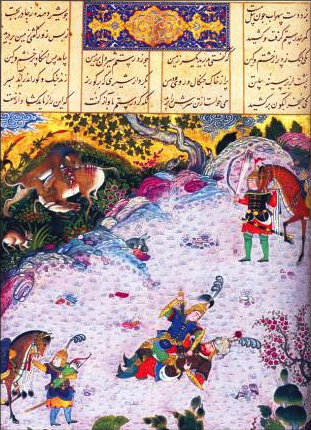

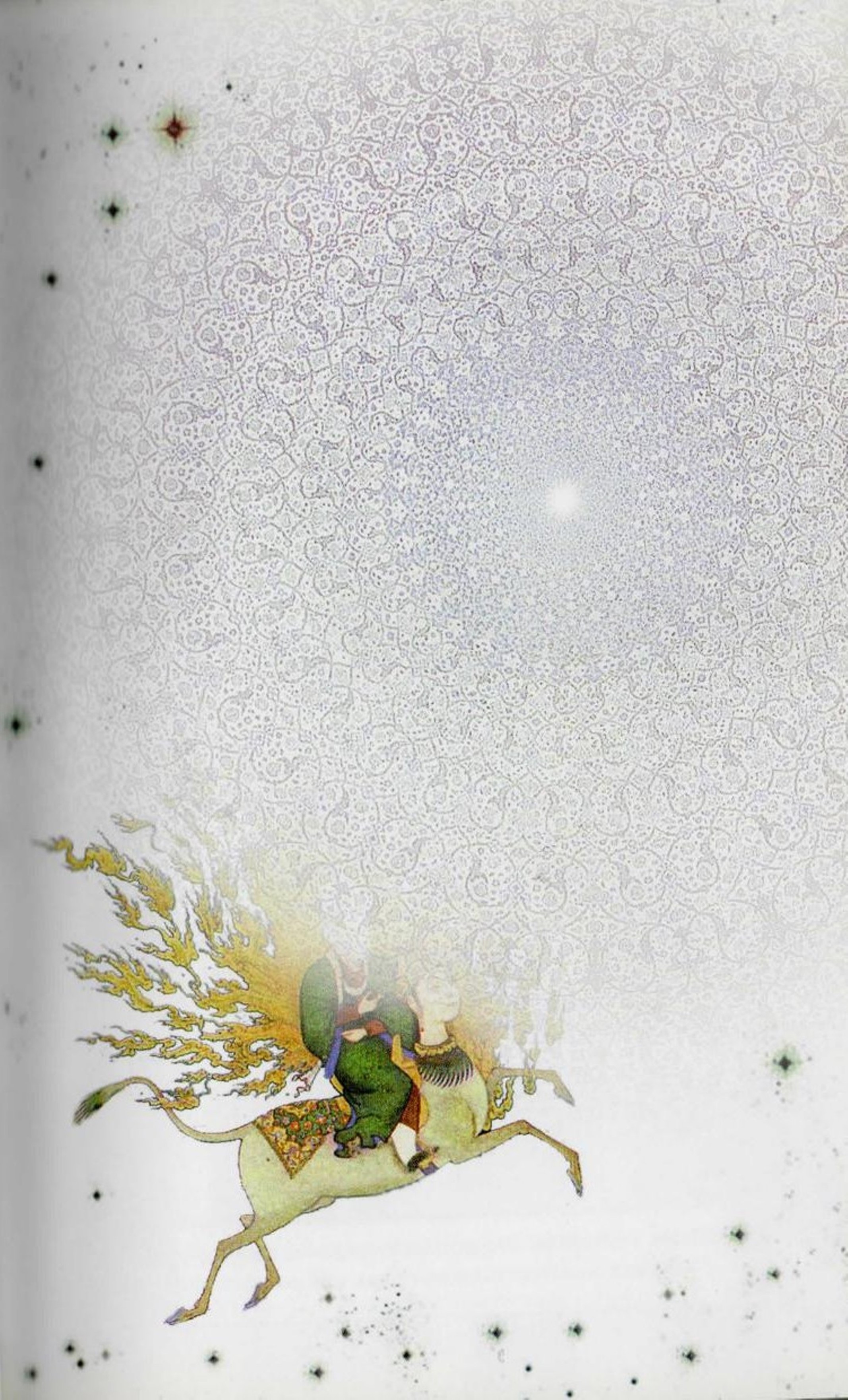

“The entire Koran is a symbolic, allusive (ramz) story, between the Lover and the Beloved”. Image: Rumi and Shams-i Tabrīzī, Face to Face.

Prayer for the XXI century

Prayer for the XXI century – Download here The Prayer is an excellent act, but its spirit and meaning are more excellent than its form, even as the human spirit is more excellent and more enduring than the form. For … Lees verder →

Prayer for our Times

Forty rules of love Persian Sufi – Shams of Tabriz 1185-1248 Rule 1 How we see God is a direct reflection of how we see ourselves. If God brings to mind mostly fear and blame, it means there is too … Lees verder →

Prayer of the Heart

The Seven Days of the Heart: Prayers for the Nights and Days of the Week FREE DOWLOAD Ibn ‘Arabi (1165-1240) has long been known as a great spiritual master. His many works of prose and poetry are beginning to be … Lees verder →

The Prayer of Brother Klaus

Nicholas of Flüe (German: Nikolaus von Flüe; 1417 – 21 March 1487) was a Swiss hermit and ascetic who is the patron saint of Switzerland.[1] He is sometimes invoked as Brother Klaus. A farmer, military leader, member of the assembly, … Lees verder →

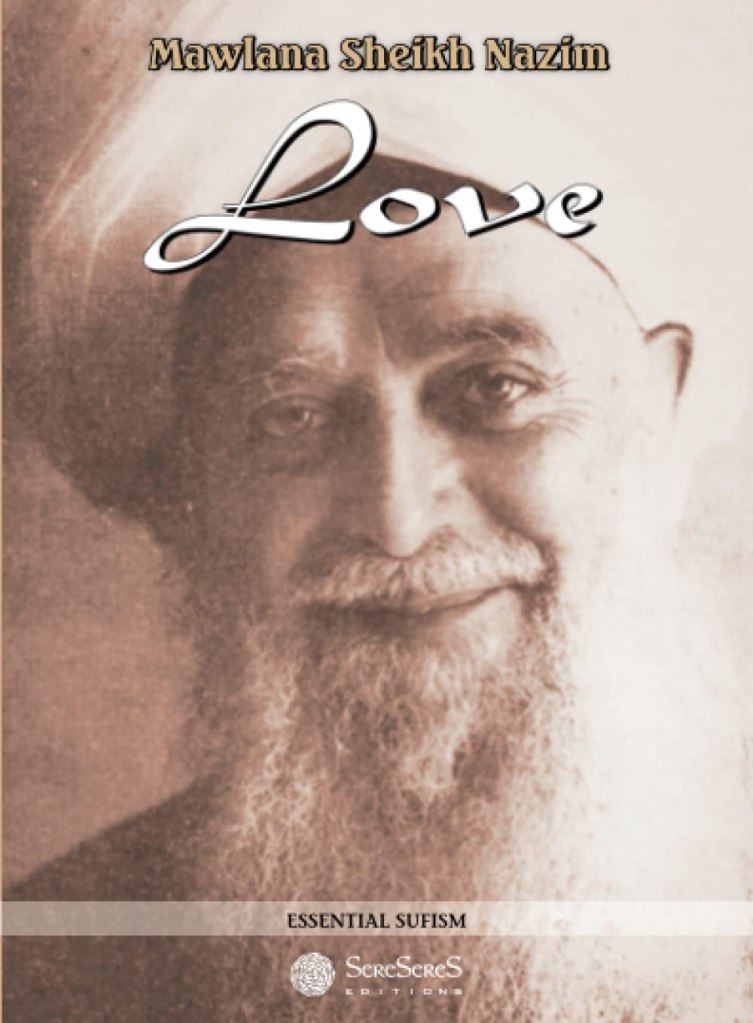

Love

If God, Almighty and Exalted, opened the Essence of His Divine Love, everyone on earth would die from that love

Mawlana Sheikh Nazim

This book is a compilation of sohbets about Love delivered by Mawlana Sheikh Nazim. “Love is the water of life. God created Adam from clay and water. If it were not for water the clay would hold no shape. Divine Love is what binds our souls together. That is why people become so miserable when they feel unloved. It is a feeling that something essential is missing from one’s life, that life itself is incomplete, and in the face of this ache, people set out in search of love with the desperation of a man dying of thirst. Love is an attribute of God Almighty which binds His servants to Him eternally. The Lord created us and loves us; that is why everyone loves love. No one complains of love or wants it to be taken from him, but all want to be loved more.” Read Here

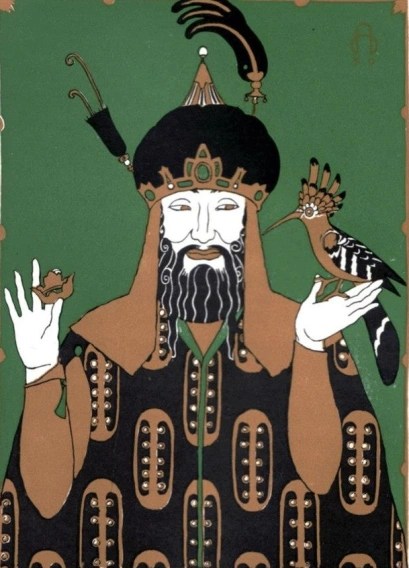

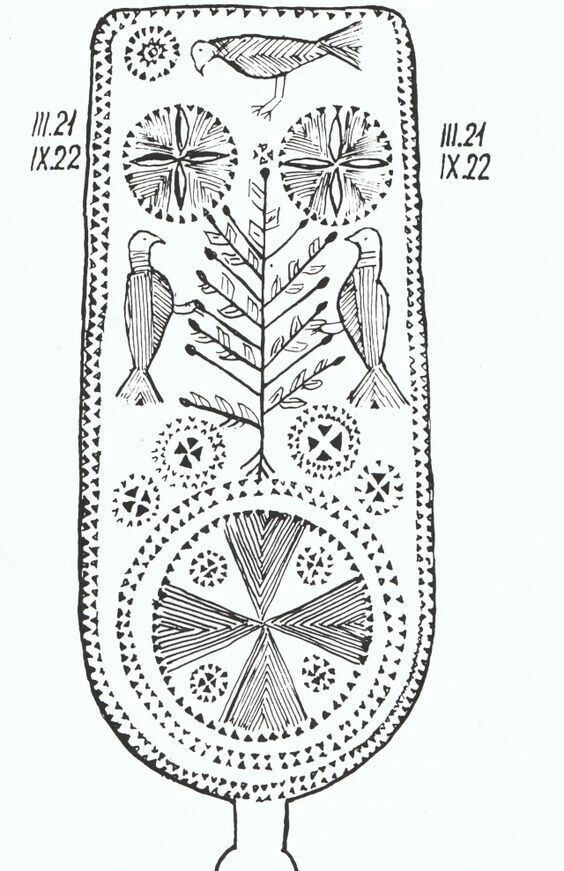

Sufism frequently uses the image of the bird to symbolize the higher or heavenly soul, a spiritual motion or inspiration, principles and states of Being. The birds are almost always associated with flowering trees, and one can see the symbol of spiritual degrees (birds) in the Divine Reality (the tree), or the symbol of the Sufi saint (the tree). ) and its inner realities (birds). The bird is associated with the soul, its cage with the body, its flight to the freedom of the spiritual consciousness flying in God.

King Solomon, Queen Sheba, and the Hoopoe: Once upon a time, says the Quran, a Hoopoe was King Solomon’s personal messenger. Read more here

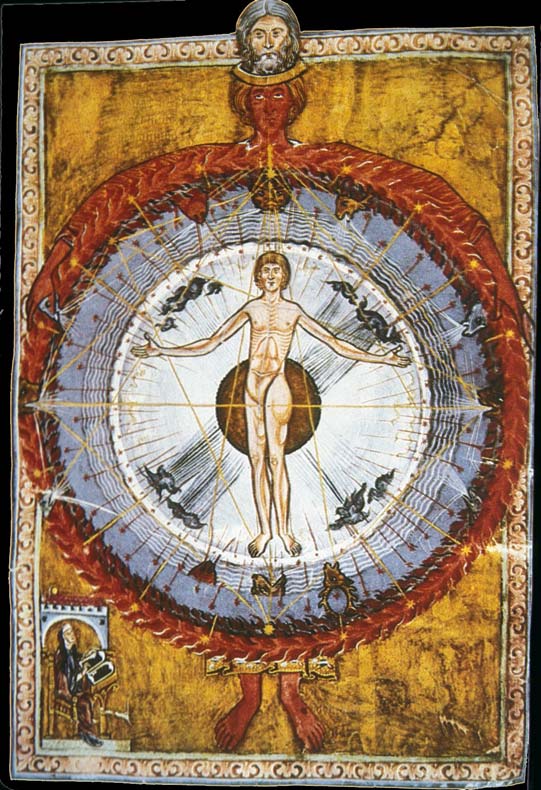

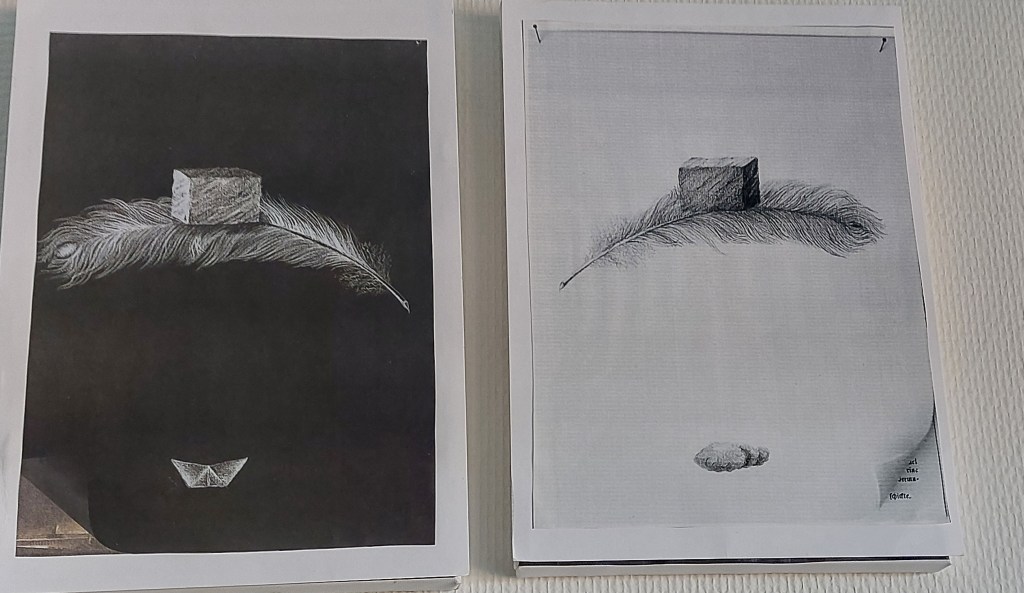

“Thus am I, a feather on the breath of God,” wrote Hildegard von Bingen of her extraordinary achievements. A 12th century German abbess, saint, composer, healer and Christian mystic, she was gifted with visions throughout her life and her works describe a visceral connection to the divine.

Symbolism of the feather

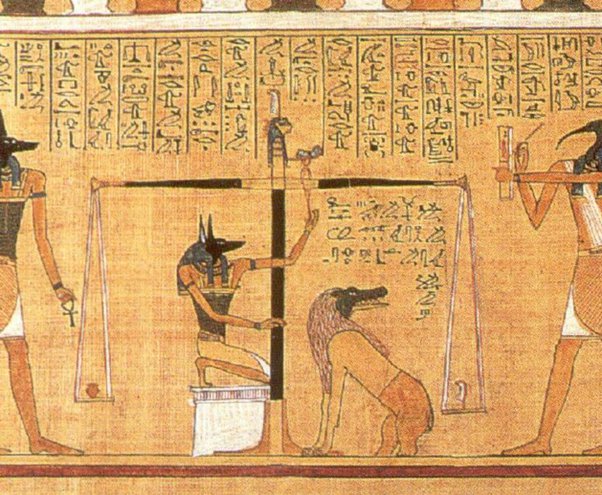

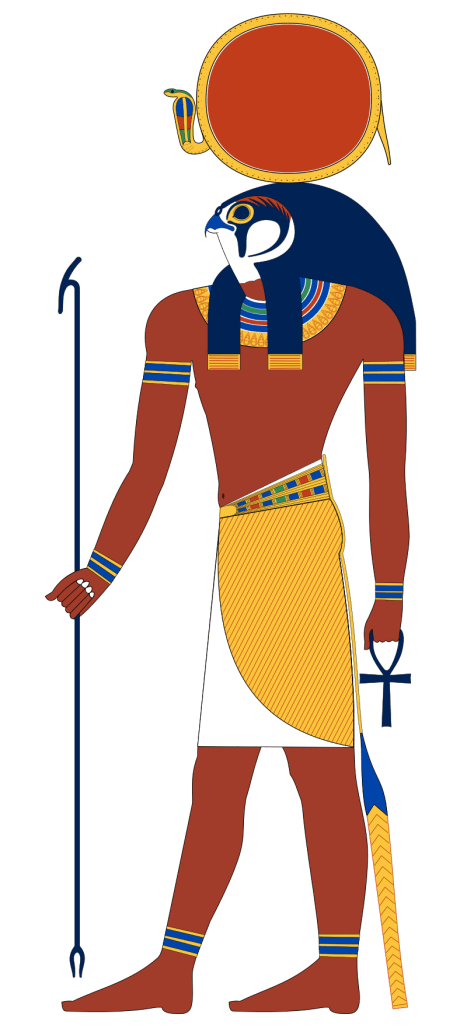

The concept of maat is central to understanding ancient Egyptian culture. In its simplest form, the term means something equivalent to ‘rightness’ and ‘orderedness’. The hieroglyphic sign for maat is a feather, and the concept was personified as the goddess Maat, who was usually depicted as a female goddess with the feather hieroglyph on her head.

From early in Egyptian history it was believed that the king’s chief responsibility was to ensure that maat was maintained in the world – i.e. in Egypt. He had to be seen to be carrying out this responsibility by, for example, defeating the country’s enemies. So, a depiction of a king engaging and destroying enemies in battle does not necessarily indicate that he himself did any real fighting. It might simply symbolise his maintenance of maat.

Egyptian temples represent the establishment of maat on earth: within their walls all is ordered correctly, whilst outside lies chaos, conceived of as a watery waste. For this reason, the walls of Egyptian temples are constructed in undulating courses.

As well as depictions of the king in battle, temple walls also frequently carried scenes showing the king presenting maat to the gods. By Ptolemaic times, 304–30 BCE, maat was believed to have come down to earth from the sky. It seems that it was thought of as a gift presented to the world by the gods, maintained by the king and returned by him in a good state.

Because he maintained maat, the period following the death of a king was potentially a very dangerous time. The next king had to take the throne as soon as possible, so that the forces of chaos could have no time to seize control.

Non-royal people were also expected to behave in a manner consistent with maat. After death, the individual would be held to account at a judgment, in which his or her heart was weighed in a balance against the feather of maat, in the ‘Hall of the Two Maats’. Those who came through the judgment process successfully were designated maa-kheru (‘true of voice’). This phrase eventually became synonymous with ‘deceased’.

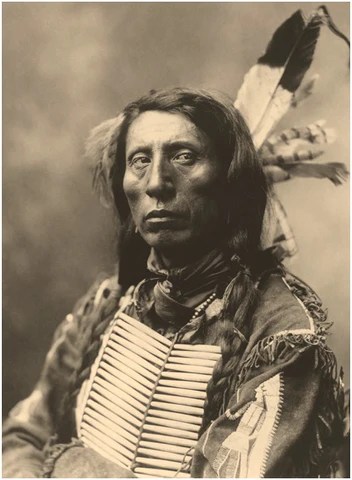

NATIVE AMERICAN FEATHER SYMBOLISM

Natural symbolism is very important in Native American culture, and the feather is a very powerful symbol for many tribal nations. Feathers are widely believed among North American Indians to signify the connection between The Creator, the owner of the feather, and the bird from whom the feather came. Deeply revered, the feather symbolizes high honor, power, wisdom, trust, strength, and freedom. As such, feathers are seen as gifts from the sky.

Eagle Feathers

Different types of feathers represent different things to Native Americans.

The most highly esteemed type of feather is that of the eagle – the bravest and strongest of all birds. The eagle flies higher and sees better than any other bird and has an unparalleled connection to the Heavens. Eagle feathers are believed to carry strong medicine and guide the mind, body and spirit towards courage, strength, and hope. Traditionally, Native American warriors were awarded an eagle feather for notable bravery (like fighting a bear) or battle victory. Only after a victory was approved by the tribal court could the feather be placed in the headpiece, and only warriors, braves, and chieftains in many tribes were awarded eagle feathers. Those who received eagle feathers wore them with pride and, to this day, eagle feathers are cared for greatly by recipients.

The highest honor to be bestowed on an American Indian is to be given the feather of a Golden or Bald Eagle. They are so highly prized, the law in the USA even recognizes the significance of eagle feathers in Native culture, tradition, and religion. While eagles are highly protected under US law, Native Americans are allowed specific exemptions to acquire, possess, and pass down eagle feathers. Only members of Federally Recognized Tribes may possess Eagle Feathers. According to current US law, unauthorized people possessing an eagle feather may be fined very large sums. As such, sometimes turkey feathers are dyed and substituted for eagle feathers for commercial purposes.

The eagle feather is considered with the same level of respect as the American flag – must be handled carefully and never allowed to drop to the ground. Feathers may be held over a person’s head as a blessing for happiness, prosperity, peace, and courage. They are also used to adorn the sacred peace pipe as a symbol of the Creator or Great Spirit.

No feather falls expectedly or without some important meaning, and feathers of all birds are valued. Symbolism includes:

- Crow = balance, skill, and cunning

- Falcon = speed, movement, and soul healing

- Dove = kindness, love, and gentleness

- Bluebird = happiness

- Hawk = guardianship and far-sightedness

- Owl = wisdom

- Raven = creation and knowledge

- Turkey = pride, fertility, and abundance

- Woodpecker = self-discovery

- Wren = protection

- Swallow = love and peace

- Kingfisher = luck

Feathers are worn, hung in the home, or otherwise displayed, as is it disrespectful to hide them away. Feathers feature heavily in dream catchers, to adorn infant cradles, to balance arrows, and hung from the home’s entrance to invite good spirits and repel bad spirits.

look also The Sun Dance: A Maypole of Wisdom for the 21th century

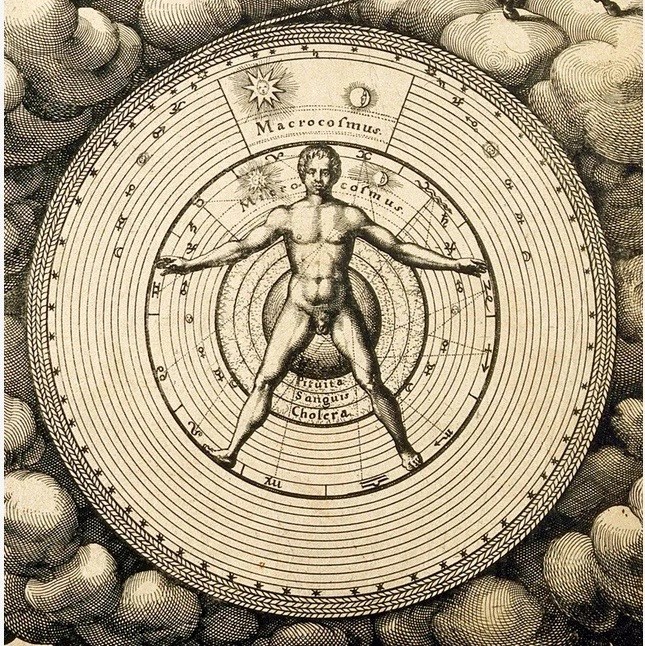

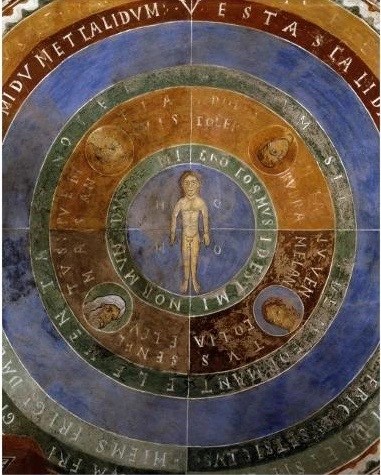

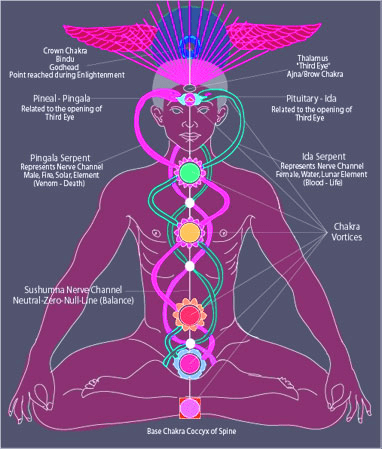

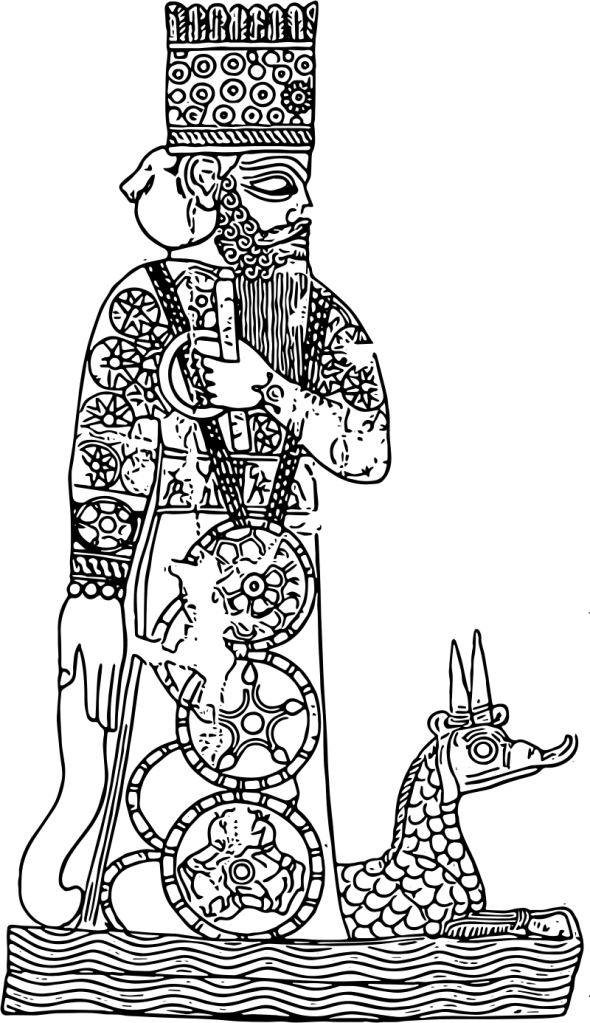

\The Angels of the Microcosm

Here we Are: The many psycho-cosmological and cosmo-physiological angels which transform the human body into a microcosm. “We who dwell on Earth can do nothing of ourselves; everything is conducted by Spirits, no less than Digestion or Sleep” (Blake, Jerusalem).

What are the “Angels of the microcosm”? Here again we find an intimation of a “subtile physiology” resulting from psycho-cosmology and cosmo-physiology, which transform the human body into a microcosm. As we know, since each part of the cosmology has its homologue in man, the whole universe is in him. And just as the Angels of the macrocosm sprang from the faculties of the Primordial Man, from the Angel called Spirit (Rūḥ), so the Angels of the microcosm are the physical, psychic, and spiritual faculties of the individual man.

Represented as Angels, these faculties are transformed into subtile centers and organs; the construction of the body envisaged in subtile physiology takes on the aspect of a minor, microcosmic angelology; allusions to it are frequent in all our authors. It is in relation to this microcosm transformed into a “court of Angels” that the mystic performs the function of lmam.

The Godhead is in mankind as an Image is in a mirror. The place of this Presence is the consciousness of the individual believer, or more exactly, the theophanic Imagination invested in him.

Becoming alive and transparent, the Temple reveals the secret it concealed, the “Form of God” which is the Self (or rather the Figure which eminently personifies it) and makes it known as the Mystic’s divine Alter Ego.

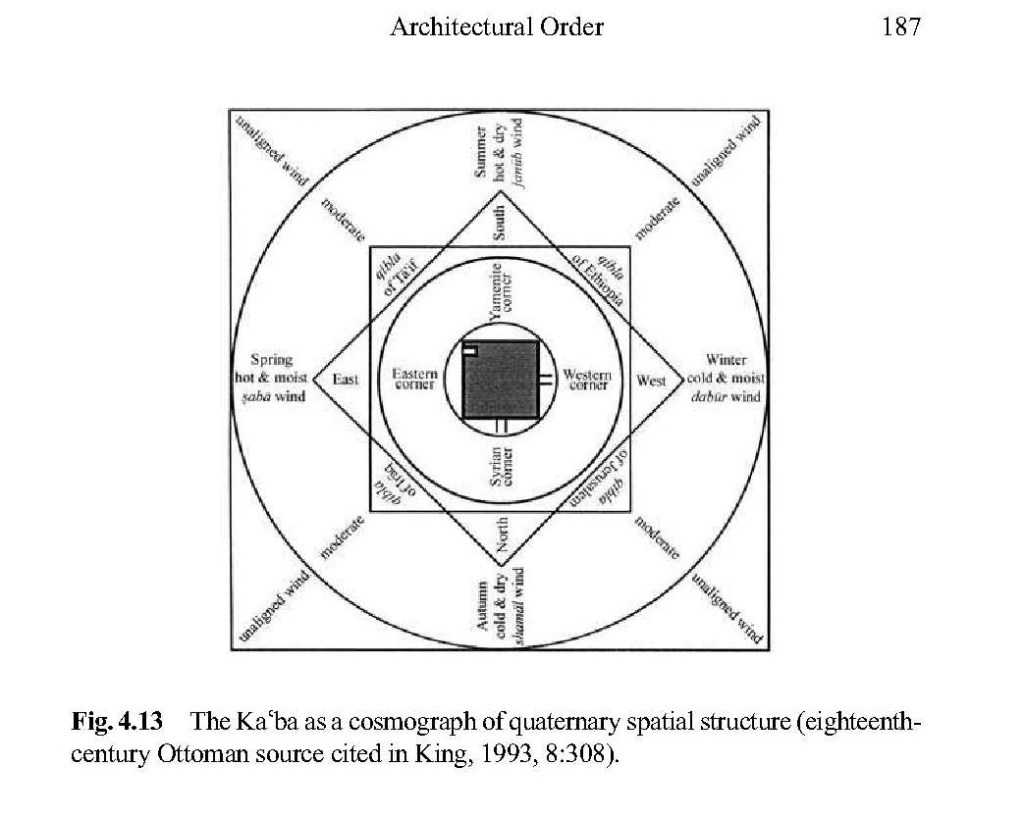

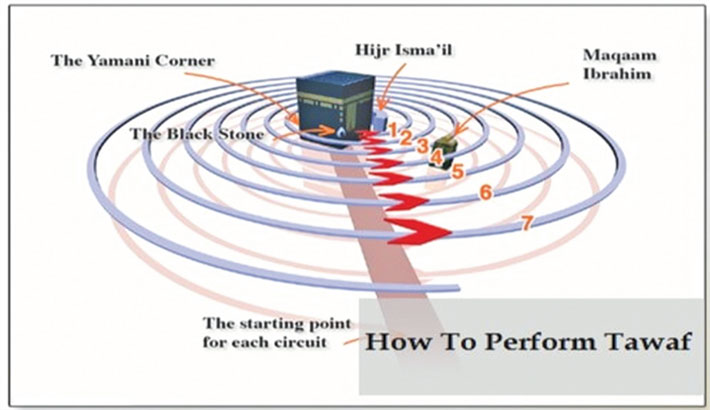

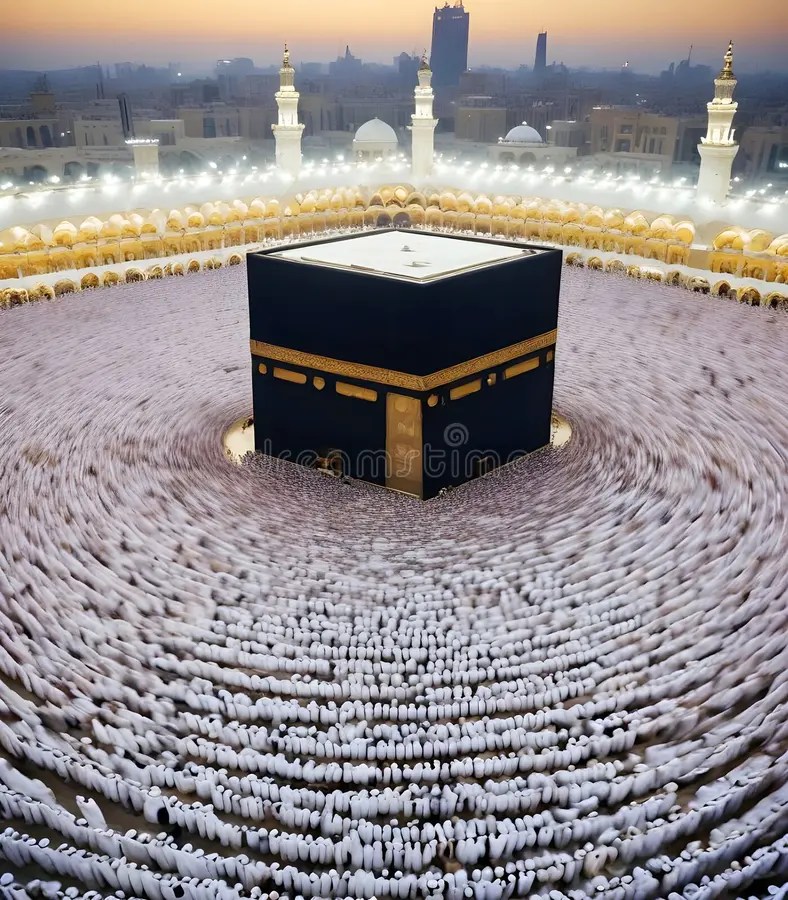

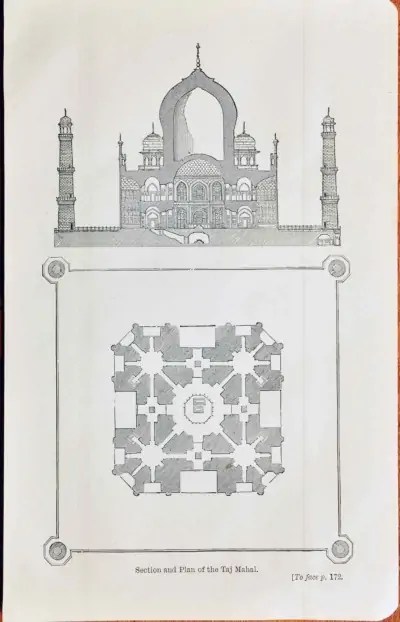

Thus the being who is the mystic’s transcendent self, his divine Alter Ego, reveals himself, and the mystic does not hesitate to recognize him, for in the course of his quest, when confronting the mystery of the Divine Being, he has heard the command: “Look toward the Angel who is with you and who accomplishes the circumambulations beside you.” He has learned that the mystic Ka’aba is the heart of being. It has been said to him: “The Temple which contains Me is your heart.” The mystery of the Divine Essence is no other than the Temple of the heart, and it is around the heart that the spiritual pilgrim circumambulates.

The Master Self and Emissary Self

“Accomplish the circumambulations and follow my footsteps,” the mystic Youth now commands him. The Youth’s point of emergence situates him as the homologue of the Angel in respect of the mystic; he is the mystic’s Self, his divine Alter Ego, who projects revelation into him. Then we hear an amazing dialogue, the meaning of which seems at first to defy all human expression. For how indeed is it possible to translate what two beings who are each other can say to each other: the “Angel” who is the divine self, and his other self, the “missionary” on earth, when they meet in the world of “Imaginative Presence”?

The story which the visionary tells his confidant at his bidding is the story of his Quest, that is to say, a brief account of the inner experience from which grew the fundamental intuition of Ibn ‘Arabî‘s theosophy. It is this Quest that is represented by the circumambulations around the Temple of the “heart,” that is, around the mystery of the Divine Essence.

But the visionary is no longer the solitary self, reduced to his mere earthly dimension in the face of the inaccessible Godhead, for in encountering the being in whom the Godhead is his companion he knows that he himself is the secret of the Godhead (sirr al-rubilblya), and it is their “syzygia,” their twoness which accomplishes the circular processional: seven times, the seven divine Attributes of perfection in which the mystic is successively invested.

“The Godhead is in mankind as an Image is in a mirror. The place of this Presence is the consciousness of the individual believer, or more exactly, the theophanic Imagination invested in him”. There has been a sustained and concerted attempt in the last few centuries, under the dominion of the Urizenic rationalising agency, to “de-centre” humanity from its centre of being. The people who try to do this are themselves profoundly de-centred and dissociated. Human consciousness is rooted in and a reflection of – indeed a realisation of – divine consciousness, that is to say of the consciousness of Being itself. As Meister Eckhart noted, “The eye with which I see God is the same with which God sees me”. The realisation of God itself is dependent upon the realisation of the God within humanity, the Human Imagination. The realisation of the Telos of history, of reality itself. Those who seek to de-centre Humanity, de-centre God.

One does not encounter, one does not see the Divine Essence; for it is itself the Temple, the Mystery of the heart; into which the mystic penetrates when, having achieved the microcosmic plenitude of the Perfect Man, he encounters the “Form of God” which is that of “His Angels,” that is to say, the theophany constitutive of his being. We do not see the Light; it is what makes us see and what makes itself seen in the Form through which it shines.

Never can the zawahir (manifest, visible things, phenomena) be the causes of other zawalzir; an immaterial cause (glzayr maddiya) is required (cf. in Suhrawardi the idea that that which is in itself pure shadow, screen, barzaklz, cannot be the cause of anything).

The “Temple” is the scene of theophany, the heart where the dialogue between Lover and Beloved is enacted, and that is why this dialogue is the Prayer of God.

Find your Centre: the centre is where your divinity and your humanity become one, and you become a Son of Man. In the Hermetic philosophy this alchemical process is called Self-Realisation.

Henry Corbin (1903-1978) was a philosopher, theologian, Iranologist and professor of Islamic Studies at the École pratique des hautes études in Paris, France. Corbin is responsible for redirecting the study of Islamic philosophy as a whole. In his Histoire de la philosophie islamique (1964), he challenged the common view that philosophy among the Muslims came to an end after Ibn Rushd.

The three major works upon which his reputation largely rests in the English speaking world were first published in French in the 1950s: Avicenna and the Visionary Recital, Spiritual Body and Celestial Earth, and Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn ‘Arabi, from which the above extract is taken.

Corbin was an important source for the archetypal psychology of James Hillman and others who have developed the psychology of Carl Jung. The American literary critic Harold Bloom claims Corbin as a significant influence on his own conception of Gnosticism, and the American poet Charles Olson was a student of Corbin’s Avicenna and the Visionary Recital.

- Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn Arabl

First published in French as L’Imagination Creatrice dans le Soufisme d’Ibn ‘Arabi this profoundly moving and beautiful volume stands as one of the great works of theology and comparative philosophy of the 20th century.

“Henry Corbin’s works are the best guide to the visionary tradition…. Corbin, like Scholem and Jonas, is remembered as a scholar of genius. He was uniquely equipped not only to recover Iranian Sufism for the West, but also to defend the principal Western traditions of esoteric spirituality.” From the 1997 Introduction by Harold Bloom

Among the more than 200 critical editions, translations, books and articles published in his lifetime, his magnum opus is without doubt the four volume En islam iranien: Aspects spirituels et philosophiques, Paris: Gallimard, 1971-73. But this has not yet been translated and its scope and magnitude make it ill-suited as an introduction to his work. Creative Imagination is the most comprehensive and accessible guide to the profoundly important and powerful spiritual treasures to be found in his writings. It is indispensible for those seeking a deeper understanding of the religious imagination and the relations among Judaism, Christianity and Islam in the modern world. Indeed, a close reading of this text may provide something of an initiation for those hoping to enter into the visionary tradition which Corbin’s work represents.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1. Between Andalusia and Iran: A Brief Spiritual Topography

2. The Curve and Symbols of Ibn ‘Arabi’s Life

3. The Situation of Esotericism

PART ONE: SYMPATHY AND THEOPATHY

Ch. I. Divine Passion and Compassion

Ch II. Sophiology and Devotio Sympathetica

PART TWO: CREATIVE IMAGINATION AND CREATIVE PRAYER

Ch. III. The Creation and Theophany

Ch. IV. Theophanic Imagination and Creativity of the Heart

Ch. V. Man’s Prayer and God’s Prayer

Ch. VI. The “Form of God”

EPILOGUE

Translated from the French by RALPH MANHEIM Here Free Download

It’s a fascinating new experience: Me! Years go by, life experience accumulates. We slowly discover that our self-entity exists within an atmosphere of aloneness and separation. Our first instinct is to break out of the isolation with a lot of grasping and pos-sessing—friends, lovers, food, cars, money, land, whatever. We try to dull the ache with entertainment, understand it with philosophy, or accept it in therapy. No matter. Nothing quite delivers the abiding wholeness we sense is really the way we ought to be.

It’s a fascinating new experience: Me! Years go by, life experience accumulates. We slowly discover that our self-entity exists within an atmosphere of aloneness and separation. Our first instinct is to break out of the isolation with a lot of grasping and pos-sessing—friends, lovers, food, cars, money, land, whatever. We try to dull the ache with entertainment, understand it with philosophy, or accept it in therapy. No matter. Nothing quite delivers the abiding wholeness we sense is really the way we ought to be.

The Prayer is a deep psycho-logical force field to help us over-come our mole-like resistances to the light. The Prayer is an unfolding series of archetypal motions and gestures that appear in endless variation throughout all the devotional practices of the human family.

The Prayer is a deep psycho-logical force field to help us over-come our mole-like resistances to the light. The Prayer is an unfolding series of archetypal motions and gestures that appear in endless variation throughout all the devotional practices of the human family.