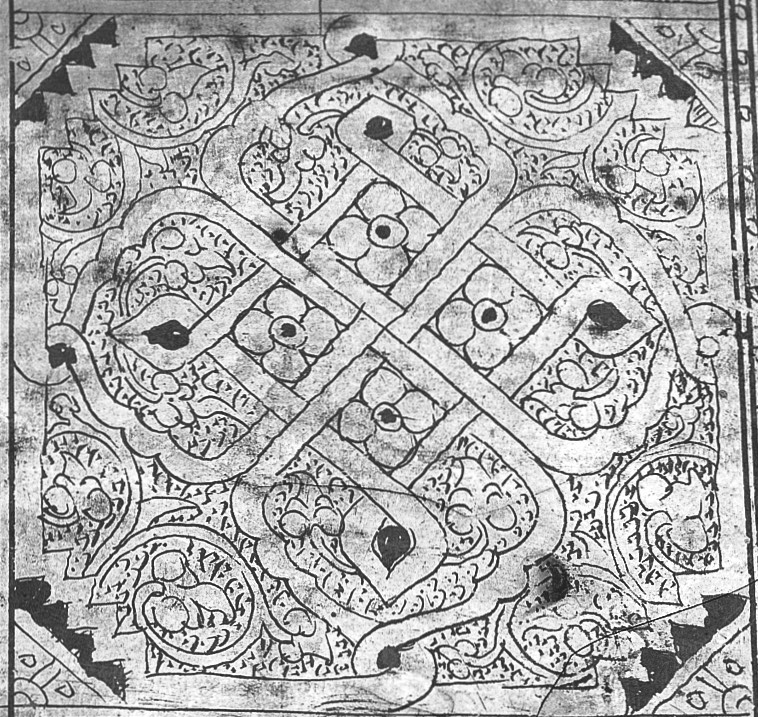

Celtic knotwork design

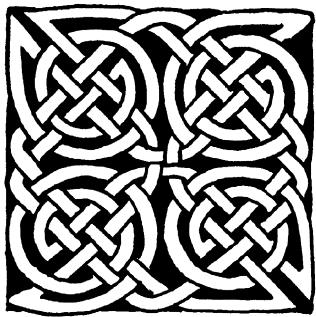

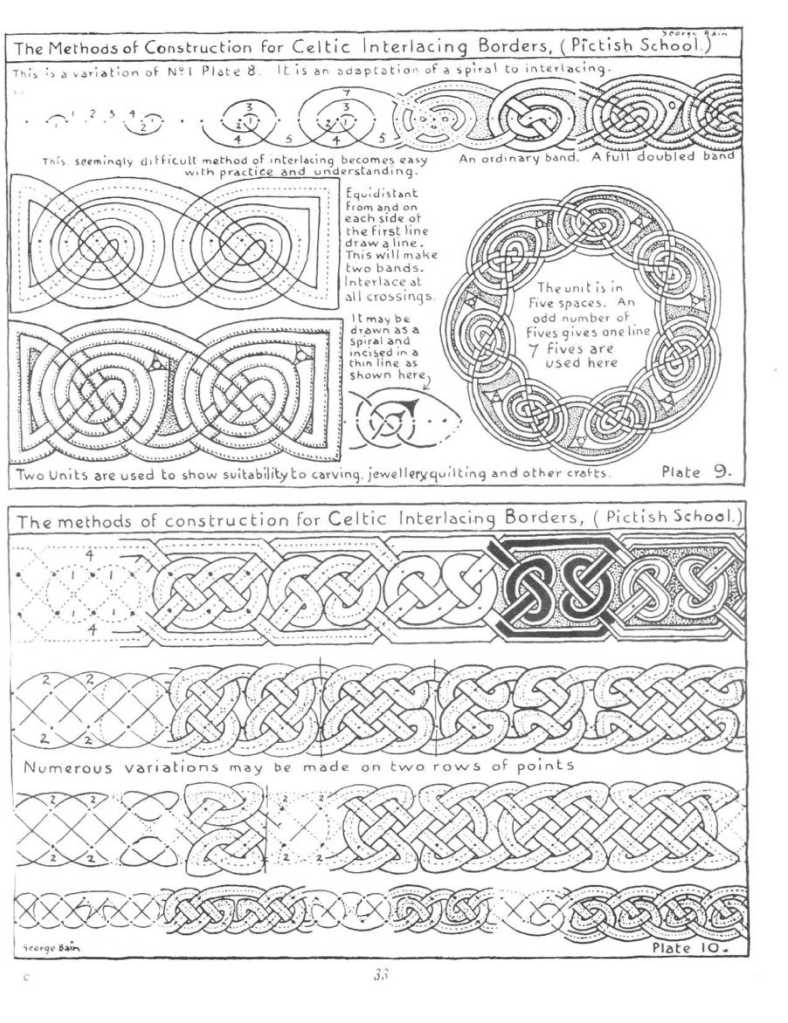

Perhaps the most familiar continuous-line drawings are the knotwork designs of Celtic art that were used to decorate metalwork, stone monuments, and manuscripts like the famous Book of Kells. George Bain, who unraveled the methods used in constructing these complex designs, found their astonishing complexity to be based on a few simple geometrical principles.

Bain’s research highlighted the connections between Celtic art and its religious, legal, and philosophical contexts. He noted that the use of knots and interlace motifs was often influenced by religious prohibitions on figurative representation, which led to ingenious decorative strategies in manuscripts and sculpture. His work also traced design influences between ancient Mediterranean, Asian, and North-European cultures, helping to clarify the origins and meaning of Celtic visual motifs.

- Celtic knotwork often symbolizes eternity, the interconnectedness of life, or unbroken spiritual paths, as the lines have no beginning or end.

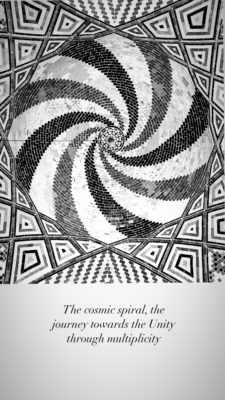

- Spirals can represent cosmic forces, spiritual development, or cycles of birth and rebirth, especially in Insular and Pictish traditions.

- Zoomorphic elements—where knots morph into animal forms—may evoke mythic creatures, protective spirits, or ancestral lineage, blending art with storytelling.

Referring to a page of the “Book of Armagh,” Professor J. O. Westwood wrote, “In a space of about a quarter of an inch superficial, I counted with a magnifying glass no less than one hundred and fifty-eight interlacements of a slender ribbon pattern formed of white lines edged with black ones upon a black ground. No wonder that tradition should allege that these unerring lines should have been traced by angels.” One of the aims of this book is to show that there is nothing marvellous in a design having not a single irregular interlacement. Indeed, a wrong interlacement would be an impossibility to a designer conversant with the methods. One might as well marvel at a piece of knitting that had not a mistake in its looping.

Threshold tracing, Isle of Lewis, Scotland

The continuous line also survived in Scotland, where M. M. Banks documented it in 1935. In some rural areas, housewives traced such patterns in pipe clay on thresholds, the floors of houses, and in dairies and byres. The designs, not all of which were continuous-line drawings, were refreshed each morning and were thought to keep away ghosts or evil spirits. One elderly woman in Galloway said that her grandmother had explained the tradition with a couplet:

Tangled threid and rowan seed

Gar the witches lose (or lowse) their speed

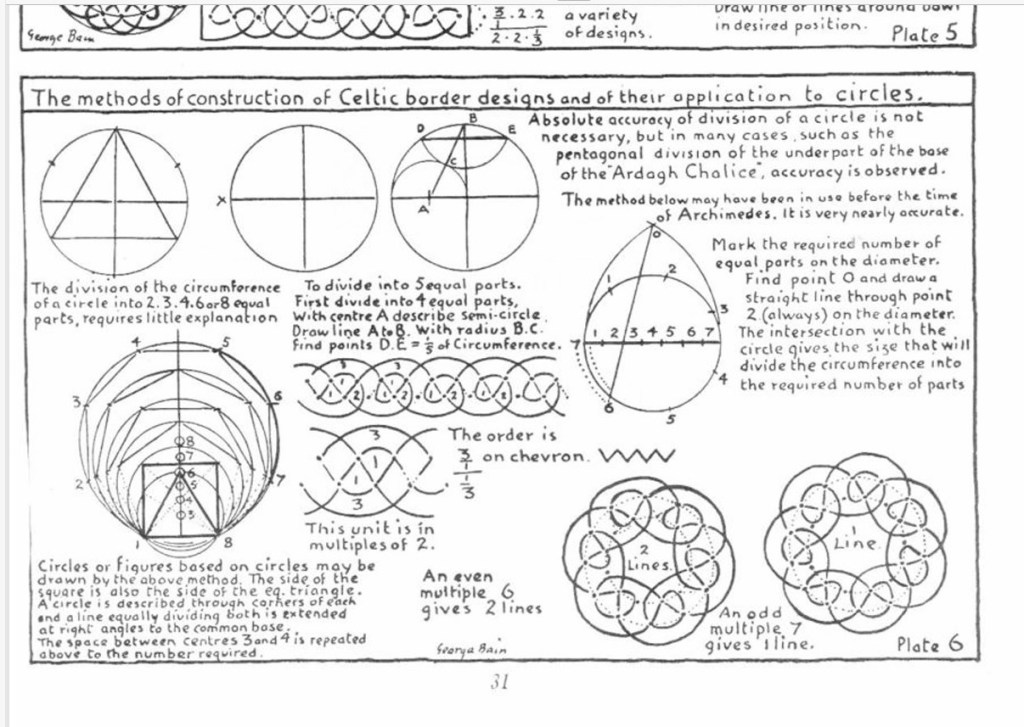

The example in Figure 18 is missing the guiding dots but a Greek vase from the 8th century B.C. with a similar design is not . The extra dots indicate the artist was imitating a design that was no longer understood. The Greeks viewed barbarian art much in the manner of modern decorators and borrowed and adapted freely.

Proto-Corinthian Greek vase, 8th century B.C.

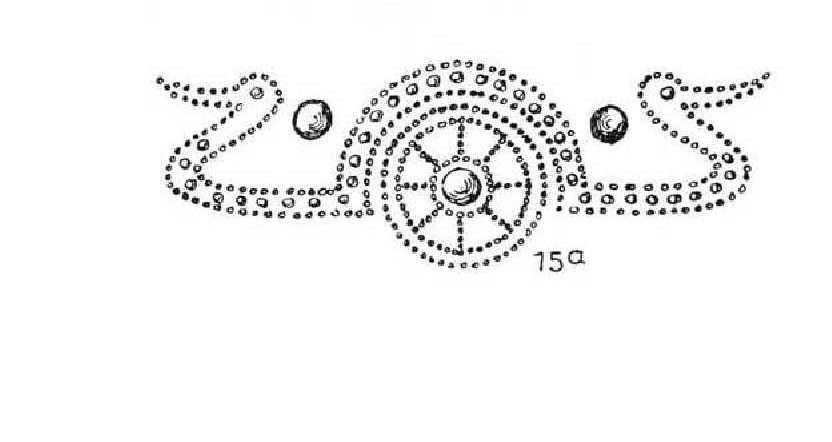

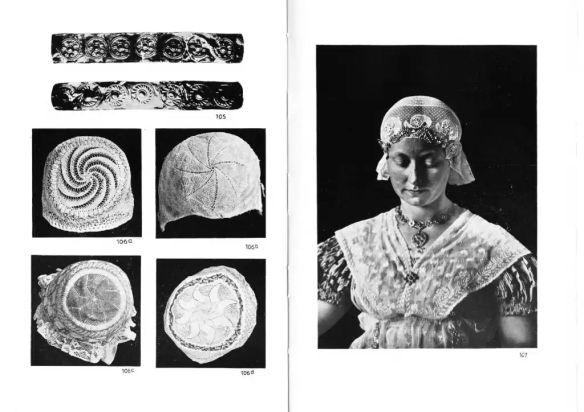

A related motif dating from at least Bronze Age times is the spiral ornament, found in Greece, Rome, Etruria and among Germanic and Celtic peoples. Spiral fibula were used to close garments while a variety of metalwork designs served as arm bands, diadems and the like . Drawn from a single piece of wire, the spiral forms a continuous path ending where it begins, a trait common to the other art forms we have been discussing.

Bronze spiral arm band, 1600 B.C., Migration Period, Europe

The art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy comments on the symbolism of the spiral fibula.

The primary sense of “broach” (= brooch) is that of anything acute, such as a pin, awl or spear, that penetrates a material; the same implement, bent upon itself, fastens or sews things together, as if it were in fact a thread. French fibule, as a surgical term, is in fact suture. It is only when we substitute a soft thread for the stiff wire that a way must be made for it by a needle; and then the thread remaining in the material is the trace, evidence and “clew” to the passage of the needle; just as our own short life is the trace of the unbroken Life whence it originates.

Drawn from a single piece of wire, the spiral fibula forms a continuous path ending where it begins.

The use of a single line to construct a work of art has a long history as we have seen and examples can be found in a wide variety of media.

It is of little importance, in the different forms that the symbolism takes, whether it be a thread in the literal sense, a cord, a chain, or a drawn line such as those already mentioned, or a path made by architectural means as in the case of the labyrinth, a path along which the being has to go from one end to the other in order to reach his goal. What is essential in every case is that the line should be unbroken.

- Symbolism shapes religious rituals, social identity, and even national icons, allowing communities to share complex ideas through shared visual language.

- The study of symbolism reveals how societies articulate meaning, bridge material and spiritual worlds, and encode important knowledge through art and tradition.

- George Bain, known as the father of the Celtic art revival, reached out and maintained contact with Ananda Coomaraswamy in the 1940s. Coomaraswamy, an esteemed art historian and philosopher specializing in Indian and Oriental art, was one of the most respected scholarly figures of that time and had a strong interest in Celtic culture throughout his career.

- Coomaraswamy admired Bain’s work, and Bain expressed mourning for Coomaraswamy’s passing in the preface to his major book “Celtic Art: The Methods of Construction,” showing a connection that underlined a Celtic-Indian cultural linkage. Their intellectual exchange is regarded as part of a broader cross-cultural dialogue that linked Eastern art traditions and philosophies with Western Celtic revival movement. Core Philosophical Themes in Celtic Tradition

- Interconnectedness and Eternity: Celtic art, especially knotwork, symbolizes the endless, interconnected nature of existence. The continuous loops without beginning or end reflect eternal life, unity, and the infinite cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

- Cycles of Life and Renewal: Many motifs, such as spirals and the triskele (triple spiral), evoke life cycles, cosmic rhythms, and transformation. These represent the soul’s journey through phases of growth, death, and spiritual renewal, aligning human life with natural and cosmic forces.

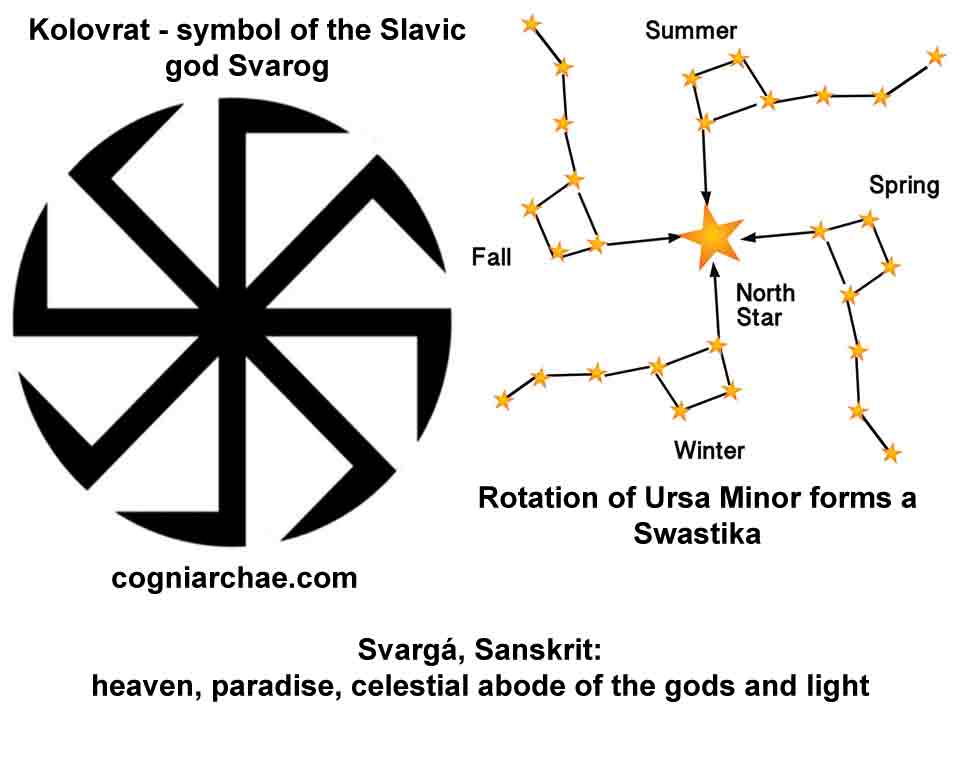

- Nature and Spiritual Vitality: Celts believed all elements of nature—rivers, rocks, animals, the sun, and the moon—possess spirit and power. This animistic belief is expressed in symbols that honor natural forces and the sacred balance between earth and the cosmos.

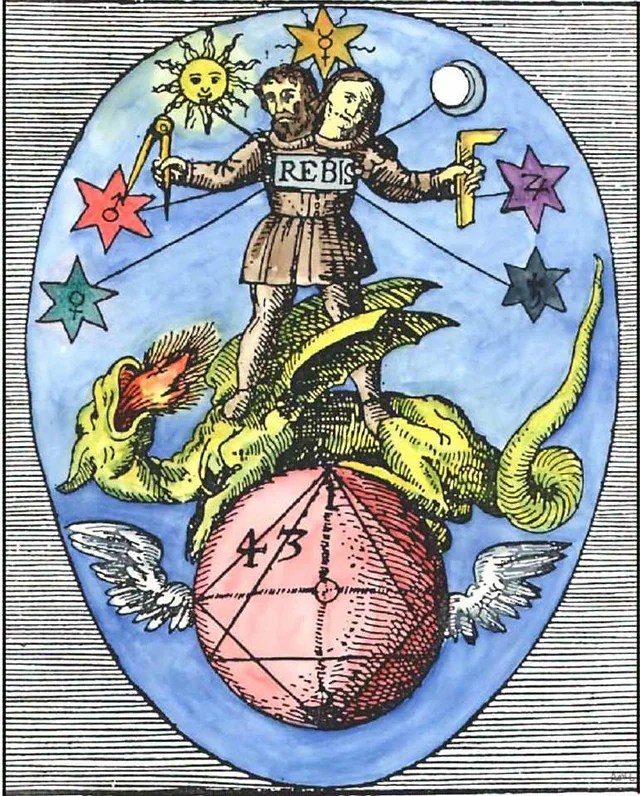

- Balance and Harmony: The Awen symbol, consisting of three rays, represents spiritual inspiration as well as the balance between opposites such as male/female energies, mind/body, and opposing cosmic forces.

- Trinity and Triplicity: Triangular and threefold symbols such as the triquetra emphasize important trinities in Celtic belief: life-death-rebirth, body-mind-spirit, or past-present-future. These forms unify spiritual, natural, and philosophical concepts in a single visual.

- Philosophical Role of Celtic Symbols

- Symbols were used as tools in rituals, healing, and oral traditions to convey wisdom and cosmic truths.

- They acted as spiritual maps for meditation and guides for eternal truths embedded in everyday life.

- Their meanings often combine Christian symbolism with pre-Christian pagan beliefs, showing cultural continuity and transformation.

- In essence, Celtic traditions and philosophies express a profound spirituality centered on eternal cycles, unity with nature, and the balance of cosmic and human forces, richly encoded in their symbolic art and motifs

- these motifs and symbolism is still to be seen in Frisian Crafmanship:

For the Frisian Eternal Knot see The wisdom of Frisian Craftmanship

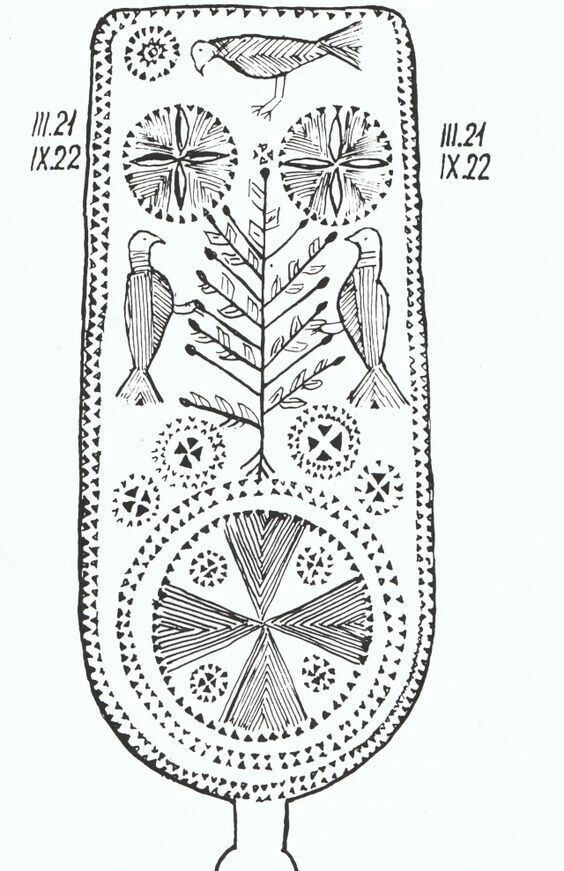

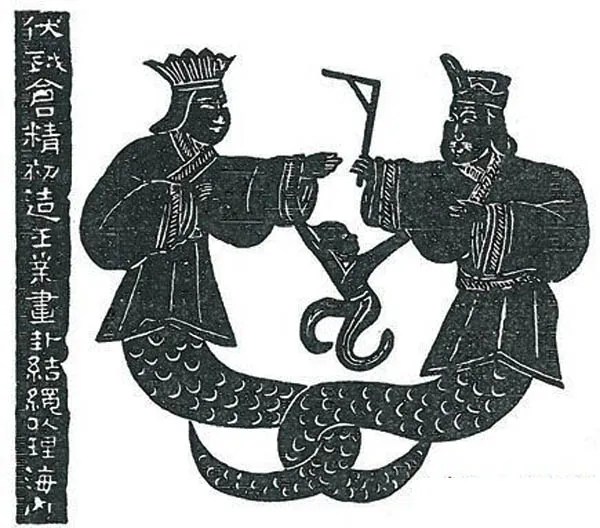

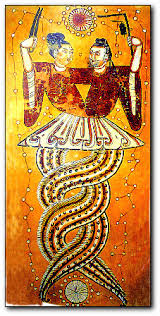

Ananda Coomaraswamy viewed the motif of two birds, especially twin or entwined birds, as deeply symbolic rather than merely decorative. He connected this symbolism across cultures, noting similarities between Celtic traditions and Indian texts like the Upanishads.

In these traditions, two birds often represent dualities or pairs of opposites—such as soul and body, divine and human, or inner and outer realities—reflecting a metaphysical unity through their relationship. Coomaraswamy saw twin birds as carriers of spiritual meaning, like “psychopomps” (soul guides) or symbols of the soul’s journey and transcendence.

This symbol appears in Celtic art as interlaced bird motifs serving not just as ornament but as a representation of life’s dual nature and spiritual truths, paralleling similar uses

in ancient Indian cosmology and philosophy. Coomaraswamy’s comparative approach highlighted how such motifs are expressions of common archetypes across cultures, embodying spiritual and philosophical ideas through natural imagery.

Ananda Coomaraswamy interpreted the motif of twin birds in myth as a profound symbol of spiritual unity and duality. In a letter to George Bain in 1947, he explained that the two birds often found in traditional design represent the friendship or unity between the “inner and outer man,” meaning the spirit and body within every person. This is also reflected in the Indian Upanishads, where two birds perched on the same tree symbolize the universal self and the individual self—the true self and the ego.

Coomaraswamy elaborated that this symbolism captures the resolution of internal conflict and self-integration, the core goal of true psychology and spiritual development. He quoted the Upanishadic passage: “Two birds, fast bound companions, clasp close the selfsame tree, the tree of life,” indicating the inseparable, complementary nature of these dual aspects.

Thus, the twin birds in Celtic art, far from mere decoration, encapsulate themes of unity, friendship, and the relationship between body and spirit—an archetype that crosses cultural boundaries between Celtic and Indian traditions alike.

The blue tit symbolizes joy, cheerfulness, hope, and positive transformation, along with deeper meanings of love, loyalty, adaptability, and spiritual renewal in various folkloric and spiritual traditions.

Joy and Positivity: The blue tit’s vibrant colors and playful behavior represent happiness,

cheerfulness, and a reminder to embrace joy and positivity even in difficult times.

Love and Loyalty: Folklore often associates blue tits with love, trust, and enduring faithfulness —these birds are monogamous and known for lifelong pair bonding, making them symbols of committed partnership and loyalty.

Hope and Renewal: Encounters with blue tits are viewed as omens of hope, new beginnings, and brighter futures after adversity.

Adaptability and Resourcefulness: Blue tits are known for their intelligence and ability to

thrive in changing environments, symbolizing resilience and making the most of available

resources.

Communication and Self-Expression: The species is vocal and expressive, offering a metaphor for clear communication and encouragement to openly share feelings and truths.

Spiritual Meaning: The blue coloration is often tied to spiritual awakening, divine intelligence,

and healing, while the bird itself might be interpreted as a messenger of spiritual guidance

and connection.

Cultural and Mythic Contexts: In Celtic and European folklore, blue tits represent good luck, honor, and protection—sometimes regarded as carriers of souls or spirits.

In sum, the blue tit in Dutch symbolism embodies themes of love, hope, joy, and spiritual

guidance, carrying a gentle but enduring message of faithfulness and renewal within the

broader tapestry of Dutch folklore and natural tradition.

- Simorgh

However, historically and mythologically, the Simorgh (or Simurgh) is a legendary Persian bird often associated with divinity, wisdom, and mythical power in Persian literature and Sufism. It is a large, benevolent, mythical bird said to possess great knowledge and spiritual

significance, sometimes seen as a symbol of the unity of all beings or divine intervention.

The Avesta (Zoroastrian holy scripture), specifically the Bahman Yasht and Rashnu Yasht,

where Simurgh is mentioned as Saêna, a divine bird associated with healing, fertility, and

divine blessing, roosting on the cosmic Tree of Life that contains all medicinal plants.

Minooye Kherad (a Zoroastrian wisdom text from the late Sassanid era), which elaborates on Simurgh’s role in healing and seeds of all plants.

The Shahnameh (The Book of Kings) by Ferdowsi, a seminal Persian epic poem from around 1000 years ago, that narrates the Simurgh raising the hero Zal, assisting in the birth of Rostam through surgical knowledge, and healing wounds with magical feathers.

“The Conference of the Birds” by Farid ud-Din Attar, a 12th-century Sufi mystical poem,

where the narrative centers on thirty birds searching for the Simurgh, eventually realizing

they themselves embody the Simurgh, symbolizing divine unity and spiritual awakening.

These texts collectively form the core of the spiritual and mystical traditions relating to the

Simurgh as a divine, healing, wise, and unifying figure in Persian and Sufi cosmologies.

The phrase “Simurgh is 30 birds” comes from the famous 12th-century Sufi poem “The

Conference of the Birds” by Farid ud-Din Attar. In this allegorical tale, a gathering of birds

embarks on a spiritual quest to find their king, the Simurgh. The journey involves crossing

seven valleys symbolizing the stages of spiritual growth.

Out of the many birds on this journey, only thirty complete it and reach the Valley of Simurgh.

When they finally meet the Simurgh, they are astonished to discover that the Simurgh itself is none other than their collective selves. The name “Simurgh” is a pun in Persian: “si” means thirty and “morgh” means birds, hence “thirty birds.” This revelation symbolizes the spiritual realization that the divine they sought is actually the true nature of themselves, emphasizing unity and self-realization.

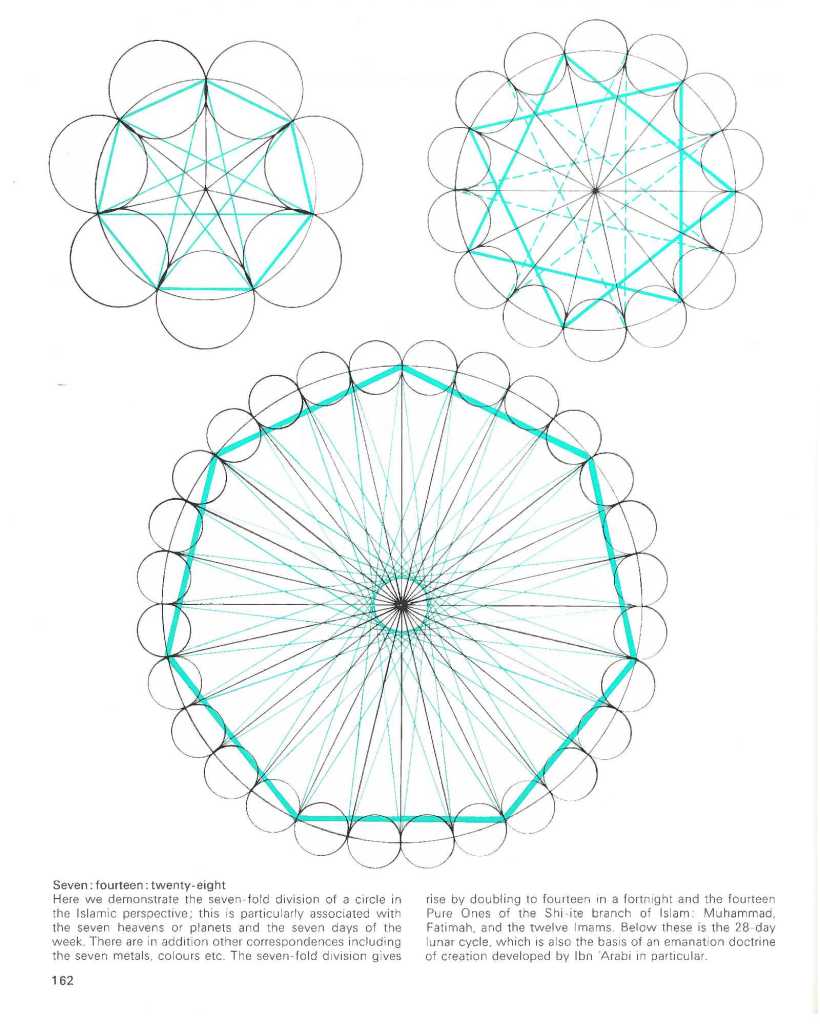

Meaning of the Eternal Knot with the Number 7

The Eternal Knot itself symbolizes: Infinity , the cycle of life and death,The connectedness of everything in the universeThe intertwining of time , space , and consciousness

When you combine this with the sacred number 7 , you get a powerful spiritual deepening.

Symbolism of the Number 7

The number 7 is found in almost every spiritual tradition as a number of holiness , mysticism , and completion . Some examples:

| Tradition / Culture | Symbolism of 7 |

| Buddhism | Seven Steps of the Buddha after His Birth |

| Hinduism | Seven chakras (energy points) |

| Christianity | Seven days of creation |

| Judaism | Seven-branched candelabra ( Menorah ) |

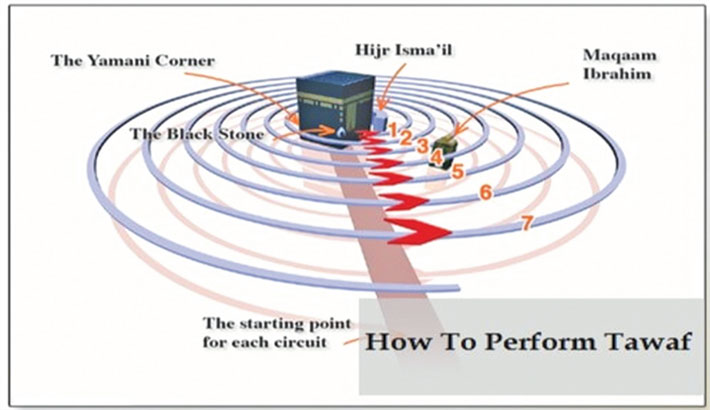

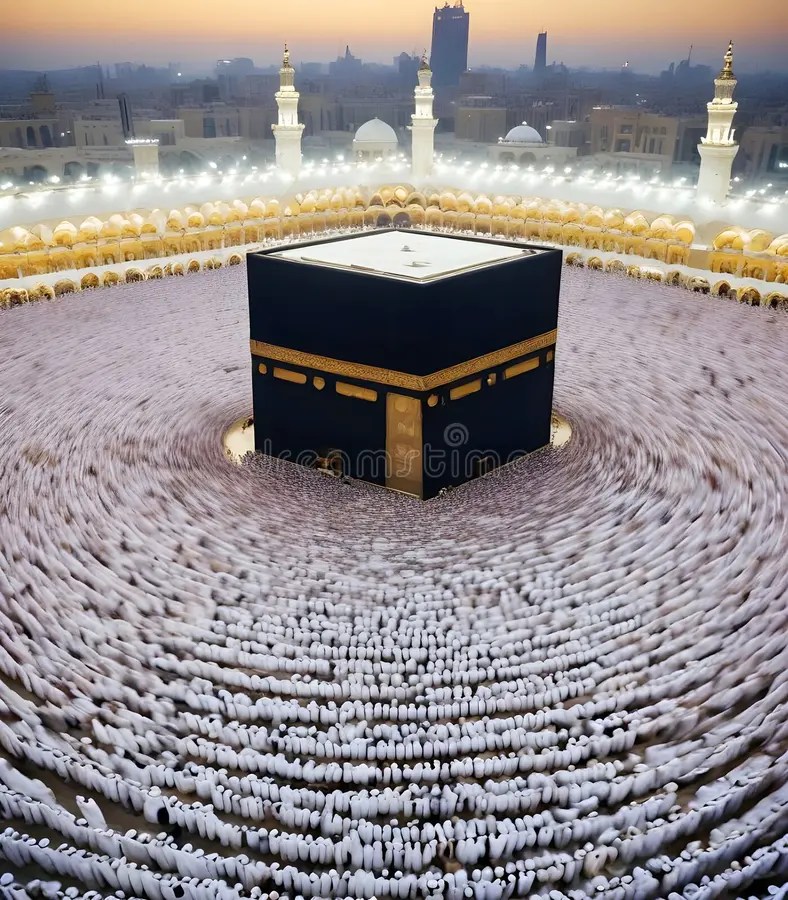

| Islam | Seven heavens, seven rounds around the Kaaba |

| Nature & Cosmos | Seven celestial bodies visible to the naked eye |

What does an Eternal Knot of 7 mean?

An Eternal Knot with 7 loops or connections represents:

Perfect connection of body, mind and soul

The eternal cycle of transformation and spiritual growth in 7 phases

The coming together of timelessness (knot) and completeness (7)

A balance between the material (the knot is tangible) and the spiritual (the symbolism of 7)

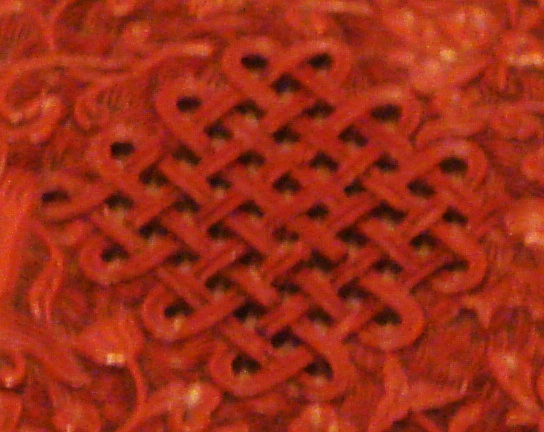

The Eternal Knot , also known as the Infinity Knot , is a powerful symbol found in several spiritual traditions, most notably within Buddhism , Hinduism , and Celtic culture . Here is some background information on this fascinating symbol:

Meaning of the Eternal Knot

General Symbolism :

- The Eternal Knot consists of an endless loop of lines that have no beginning or end.

- It symbolizes infinity , the eternal cycle of life , and the interconnectedness of all things .

In Buddhism

- Known as the Shrivatsa or Endless Knot .

- One of the Eight Lucky Symbols ( Ashtamangala ) in Tibetan Buddhism.

- Stands for:

- The Buddha’s infinite wisdom and compassion .

- The connection between cause and effect (karma).

- The idea that everything in the universe is interconnected.

In Hinduism

- The knot is sometimes associated with eternal love , life cycles , and immortality .

- Also a reference to the cyclical nature of existence : birth, death and rebirth.

Celtic Culture

- Similar knots, such as the Celtic knot , are common in ancient Celtic art.

- Often represent eternal connectedness , life paths , and spiritual growth

- Frisian Eternal Knot

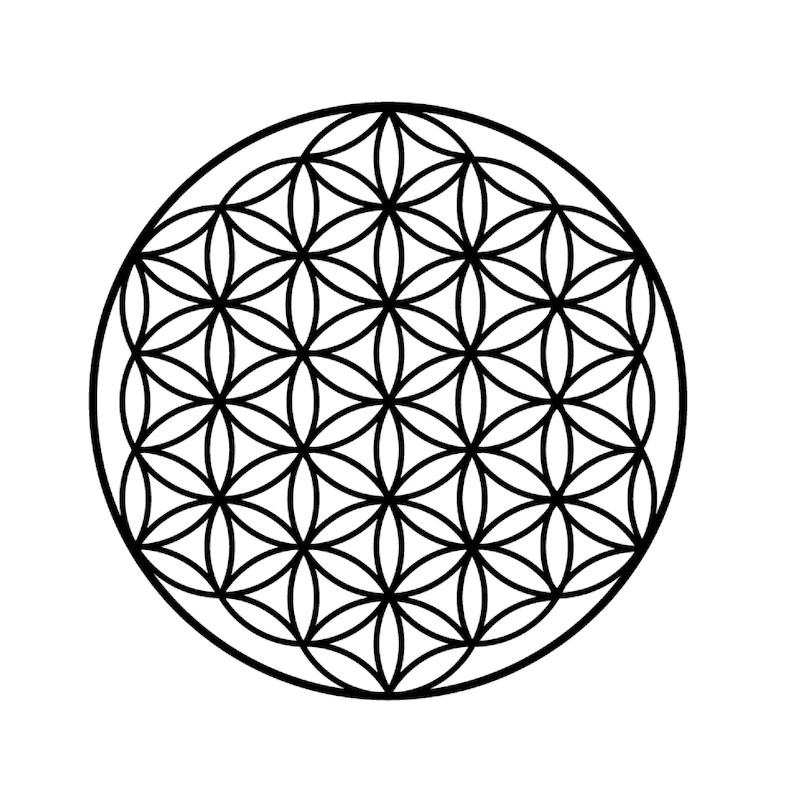

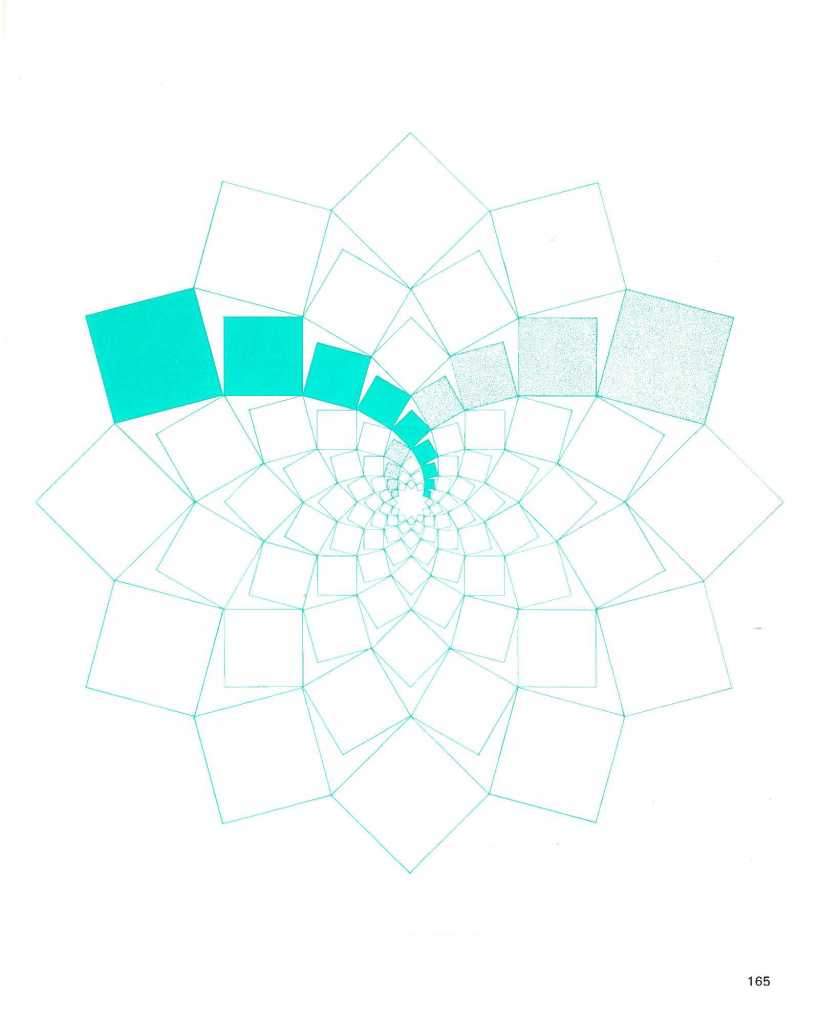

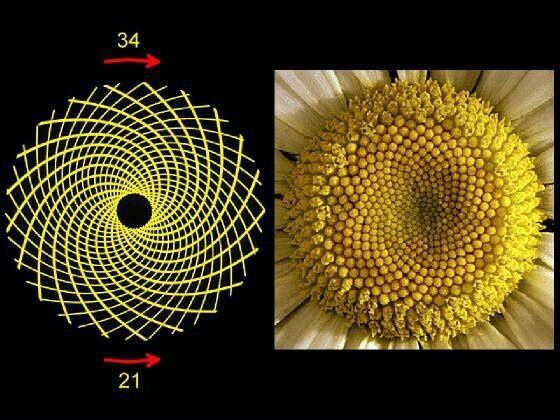

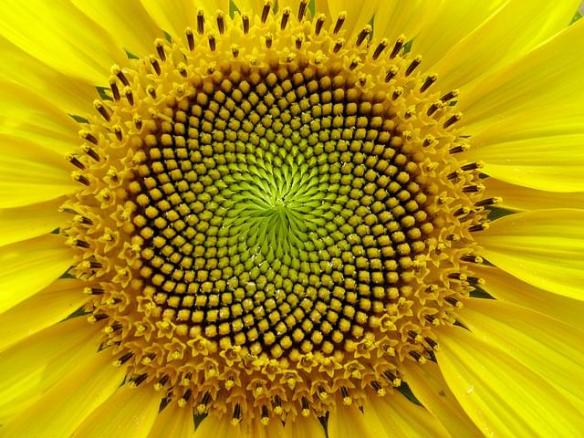

- The Flower of Life and Overlapping circles grid

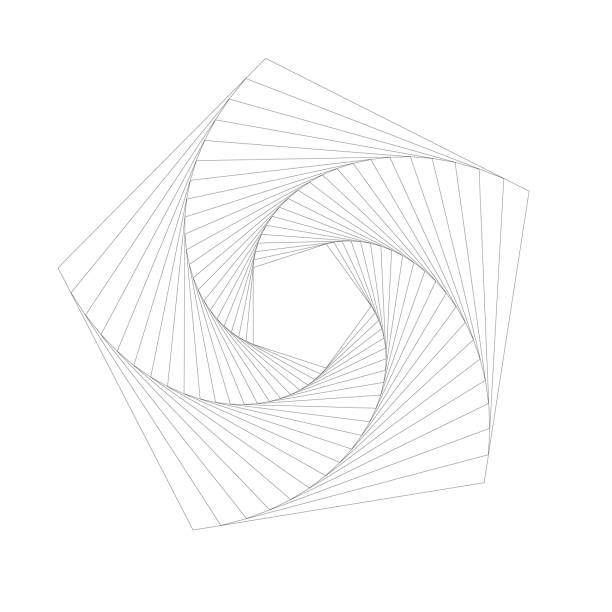

The Flower of Life is one of the most iconic symbols in sacred geometry, representing the interconnectedness of all life and the fundamental patterns of creation.

What is the Flower of Life?

The Flower of Life is a geometric figure made up of multiple evenly-spaced, overlapping circles arranged in a hexagonal pattern, resembling a flower. The pattern can expand infinitely, symbolizing endless creation and unity.

Basic Structure:

- Composed of 19 overlapping circles within a larger circle (though the pattern can extend beyond).

- Forms interlocking petals resembling flowers.

- The central design often contains the Seed of Life, which is a smaller version made of 7 circles.

Meaning and Symbolism

The Flower of Life is considered a visual expression of: Unity of all living things, Interconnectedness of the universe, Blueprint for life and creation, Sacred structure behind nature and reality

Flower of Life in NatureThe pattern reflects: See Geometry of Life – Geometry of Plants – Geometry of Human Life

- Honeycombs (hexagonal structures)

- Snowflakes

- Flower petal arrangements

- The structure of molecules and atoms

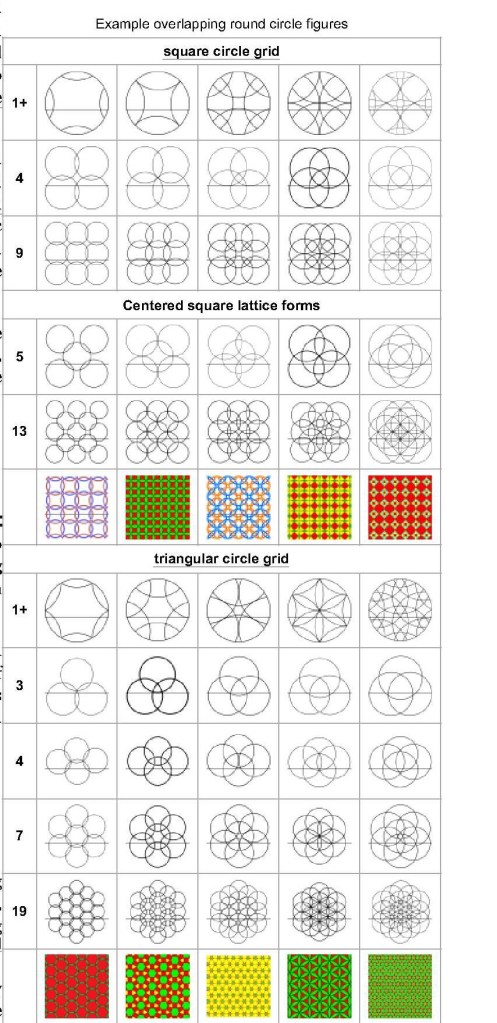

An overlapping circles grid is a geometric pattern of repeating, overlapping circles of an equal radius in two-dimensional space. Commonly, designs are based on circles centered on triangles (with the simple, two circle form named vesica piscis) or on the square lattice pattern of points.

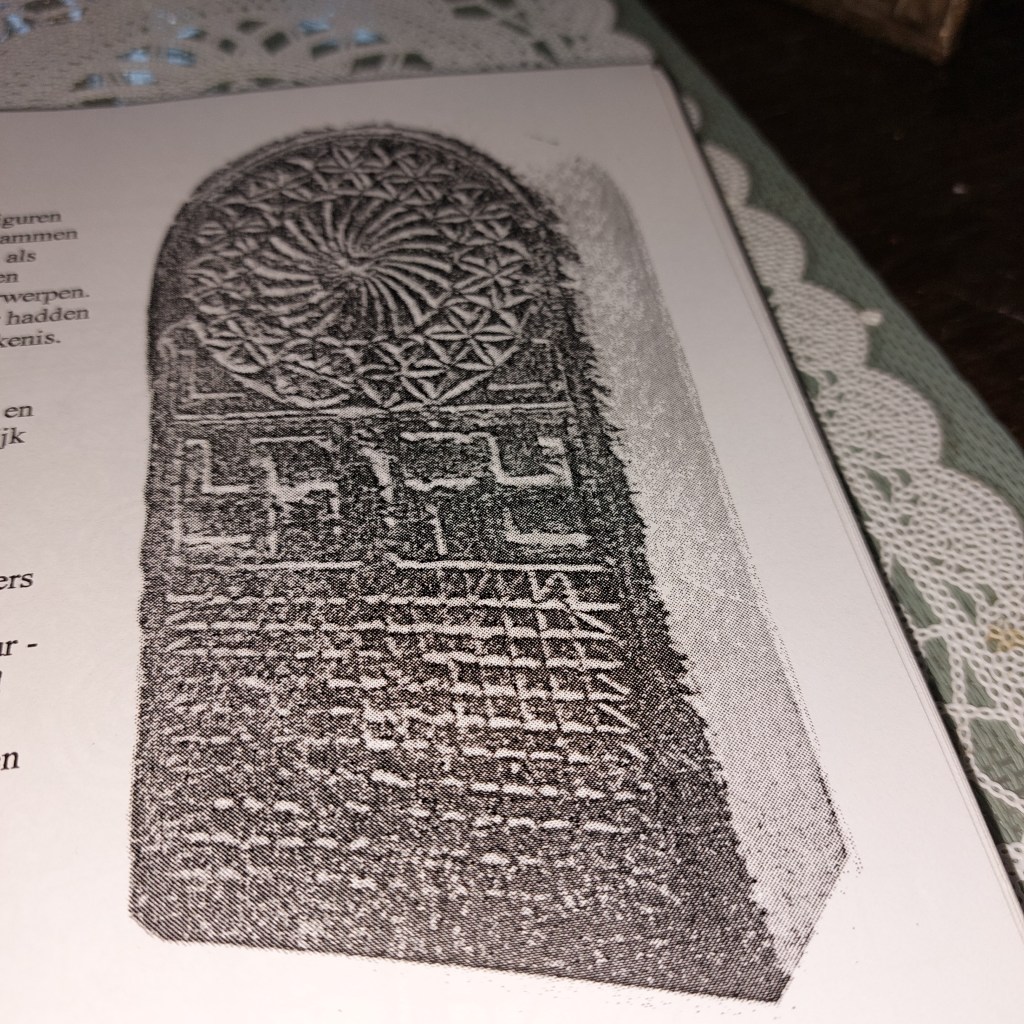

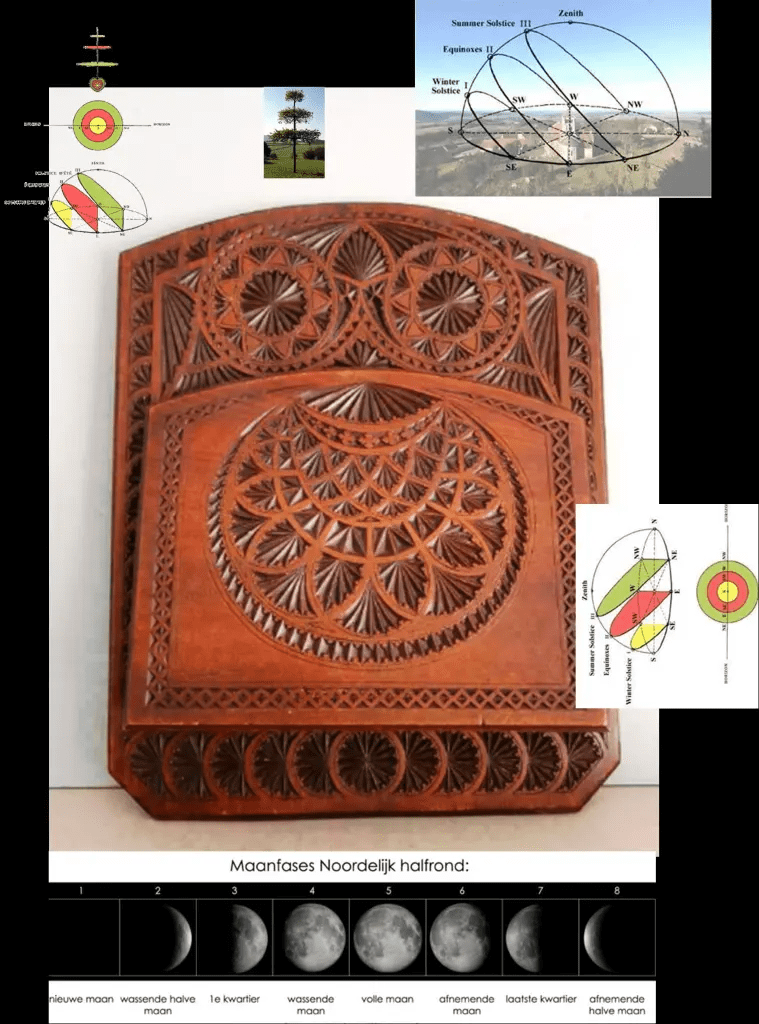

Patterns of seven overlapping circles appear in historical artefacts from the 7th century BC onward; they become a frequently used ornament in the Roman Empire period, and survive into medieval artistic traditions both in Islamic art (girih decorations) and in Gothic art. The name “Flower of Life” is given to the overlapping circles pattern in New Age publications.

Of special interest is the hexafoil or six-petal rosette derived from the “seven overlapping circles” pattern, also known as “Sun of the Alps” from its frequent use in alpine folk art in the 17th and 18th century.

Triangular grid of overlapping circles

The triangular lattice form, with circle radii equal to their separation is called a seven overlapping circles grid.[1] It contains 6 circles intersecting at a point, with a 7th circle centered on that intersection.

Overlapping circles with similar geometrical constructions have been used infrequently in various of the decorative arts since ancient times.

Cultural significance

Near East

The oldest known occurrence of the “overlapping circles” pattern is dated to the 7th or 6th century BCE, found on the threshold of the palace of Assyrian king Aššur-bāni-apli in Dur Šarrukin (now in the Louvre).[2]

The design becomes more widespread in the early centuries of the Common Era. One early example are five patterns of 19 overlapping circles drawn on the granite columns at the Temple of Osiris in Abydos, Egypt,[3] and a further five on column opposite the building. They are drawn in red ochre and some are very faint and difficult to distinguish.[4] The patterns are graffiti, and not found in natively Egyptian ornaments. They are mostly dated to the early centuries of the Christian Era[5] although medieval or even modern (early 20th century) origin cannot be ruled out with certainty, as the drawings are not mentioned in the extensive listings of graffiti at the temple compiled by Margaret Murray in 1904.[6]

Similar patterns were sometimes used in England as apotropaic marks to keep witches from entering buildings.[7] Consecration crosses indicating points in churches anointed with holy water during a church’s dedication also take the form of overlapping circles.

A girih pattern that can be drawn with straightedge and compass

Window cage at Topkapı Palace, using pattern

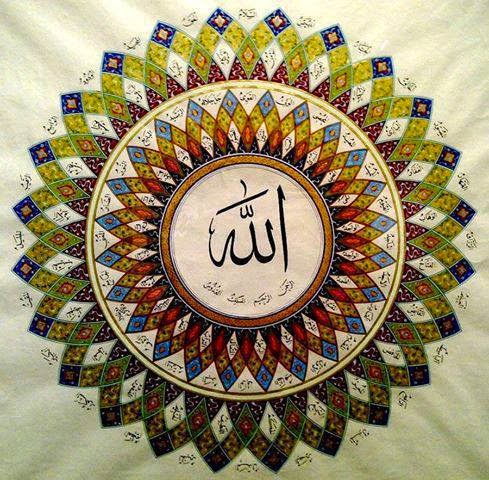

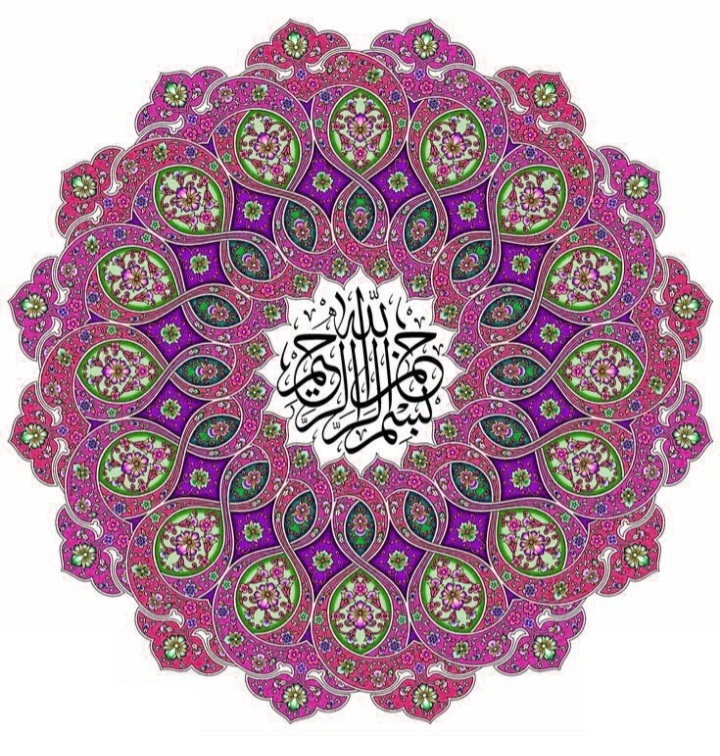

In Islamic art, the pattern is one of several arrangements of circles (others being used for fourfold or fivefold designs) used to construct grids for Islamic geometric patterns. It is used to design patterns with 6- and 12-pointed stars as well as hexagons in the style called girih. The resulting patterns however characteristically conceal the construction grid, presenting instead a design of interlaced strapwork.[8]

Europe

Patterns of seven overlapping circles are found on Roman mosaics, for example at Herod’s palace in the 1st century BC.

The design is found on one of the silver plaques of the Late Roman hoard of Kaiseraugst (discovered 1961).] It is later found as an ornament in Gothic architecture, and still later in European folk art of the early modern period.

High medieval examples include the Cosmati pavements in Westminster Abbey (13th century).[11] Leonardo da Vinci explicitly discussed the mathematical proportions of the design

See also:The Soul Carved in Wood: Romania’s Sacred Craft

Frisian Craftmanship

Frisian patterns are very comparable to Islamic Patterns. They express the same Thruth “Haqq” in Arabic and these patterns lead to the Truth. All Frisian will agree with Goethe who says:

“Stupid that everyone in his case

Is praising his particular opinion!

If Islam means submission to God,

We all live and die in Islam.”

(West-East Divan)

See:Goethe, the “refugee” and his Message for our times

see also Research Goethe Message for the 21st century

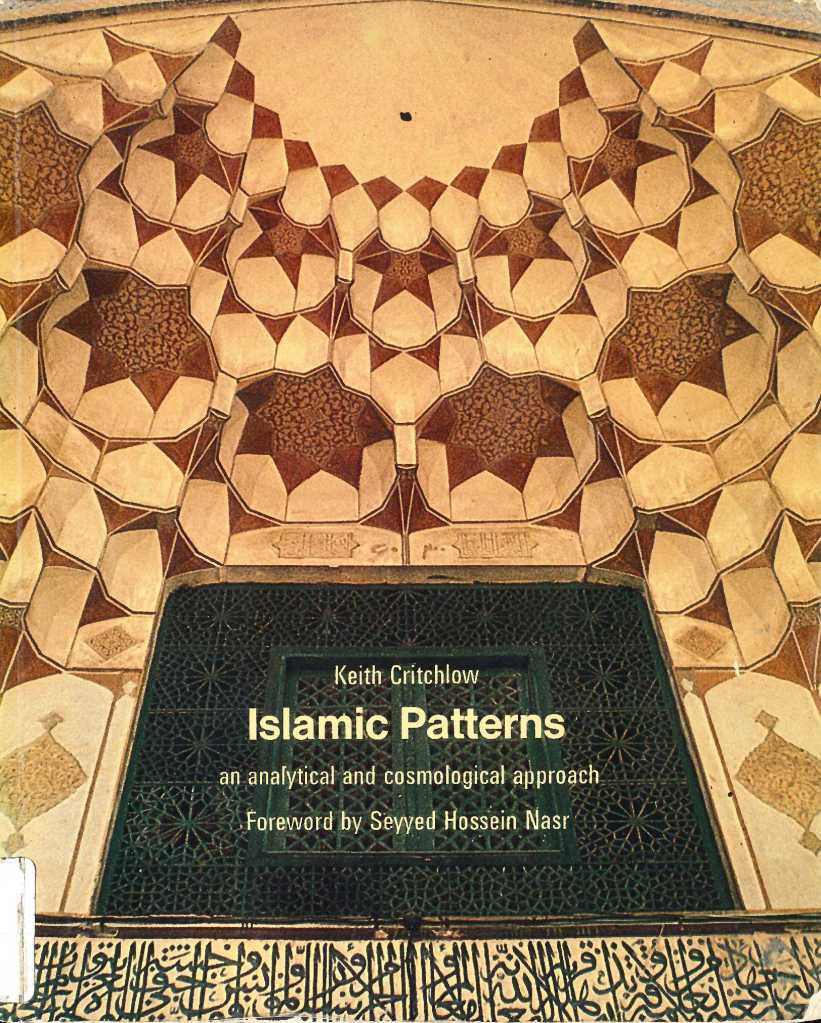

The classic study of the cosmological principles found in the patterns of Islamic art and how they relate to sacred geometry and the perennial philosophy: Is the book Islamic Patterns: An Analytical and Cosmological Approach by Keith Critchlow

For centuries the nature and meaning of Islamic art has been wrongly regarded in the West as mere decoration. In truth, because the portrayal of human and animal forms has always been discouraged on Islamic religious principles that forbid idolatry, the abstract art of Islam represents the sophisticated development of a nonnaturalistic tradition. Through this tradition, Islamic art has maintained its chief aim: the affirmation of unity as expressed in diversity.

In this fascinating study the author explores the idea that unlike medieval Christian art, in which the polarization of such forms and patterns was relegated to a background against which to set sacred images, the geometrical patterns of Islamic art can reveal the intrinsic cosmological laws affecting all creation. Their primary function is to guide the mind from the mundane world of appearances toward its underlying reality.

Numerous drawings connect the art of Islam to the Pythagorean science of mathematics, and through these images we can see how an Earth-centered view of the cosmos provides renewed significance to those number patterns produced by the orbits of the planets.

The author shows the essential philosophical and practical basis of every art creation–whether a tile, carpet, or wall–and how this use of mathematical tessellations affirms the essential unity of all things. An invaluable study for all those interested in sacred art, Islamic Patterns is also a rich source of inspiration for artists and designers. Read here the book

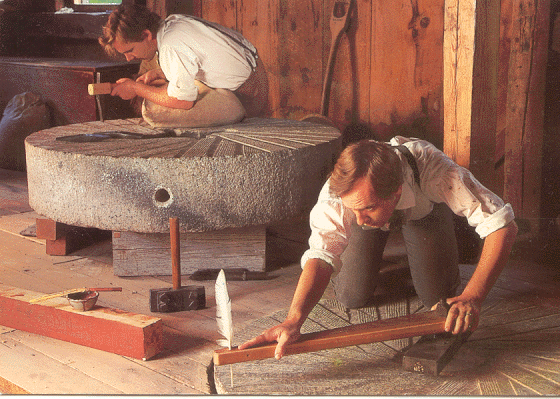

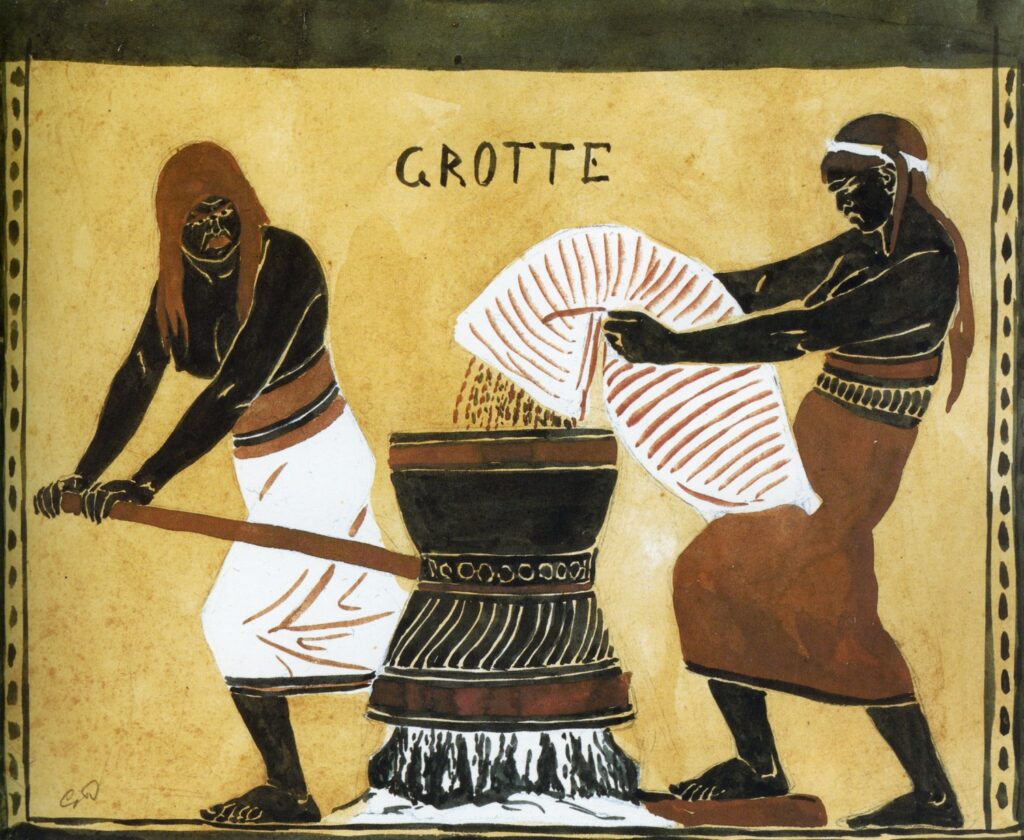

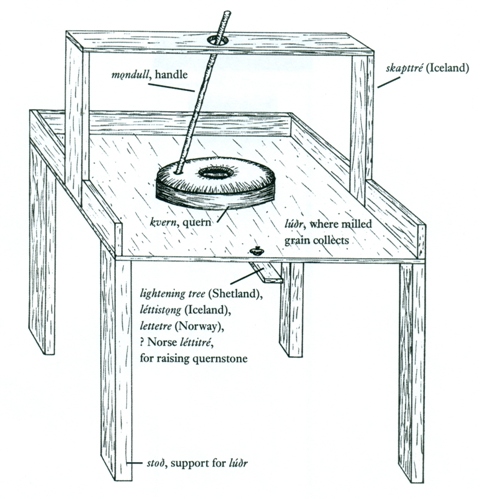

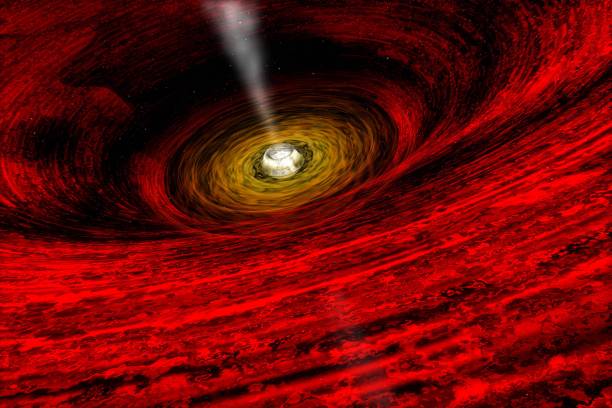

Millstone , maelstroms and Frisian craft patterns

A whirlpool is a body of rotating water produced by opposing currents or a current running into an obstacle. Small whirlpools form when a bath or a sink is draining. More powerful ones formed in seas or oceans may be called maelstroms (/ˈmeɪlstrɒm, -rəm/ MAYL-strom, – strəm).One of the earliest uses in English of the Allan Poe in his short story ” Scandinavian word malström or malstrøm was by Edgar A Descent into the Maelström” (1841). The Nordic word itself is derived from the Dutch word maelstrom (pronounced [ˈmaːlstroːm]

ⓘ ; modern spelling maalstroom), from malen (‘to mill’ or ‘to grind’) and stroom (‘stream’), to form the meaning ‘grinding current’ or literally ‘mill-stream’, in the sense of milling (grinding) grain.

Vortex is the proper term for a whirlpool that has a downdraft. In narrow ocean straits with fast flowing water, whirlpools are often caused by tides. Many stories tell of ships being sucked into a maelstrom, although only smaller craft are actually in danger.] Smaller whirlpools appear at river rapids[] and can be observed downstream of artificial structures such as weirs and dams. Large cataracts, such as Niagara Falls, produce strong whirlpools.

See The wisdom of Frisian Craftmanship

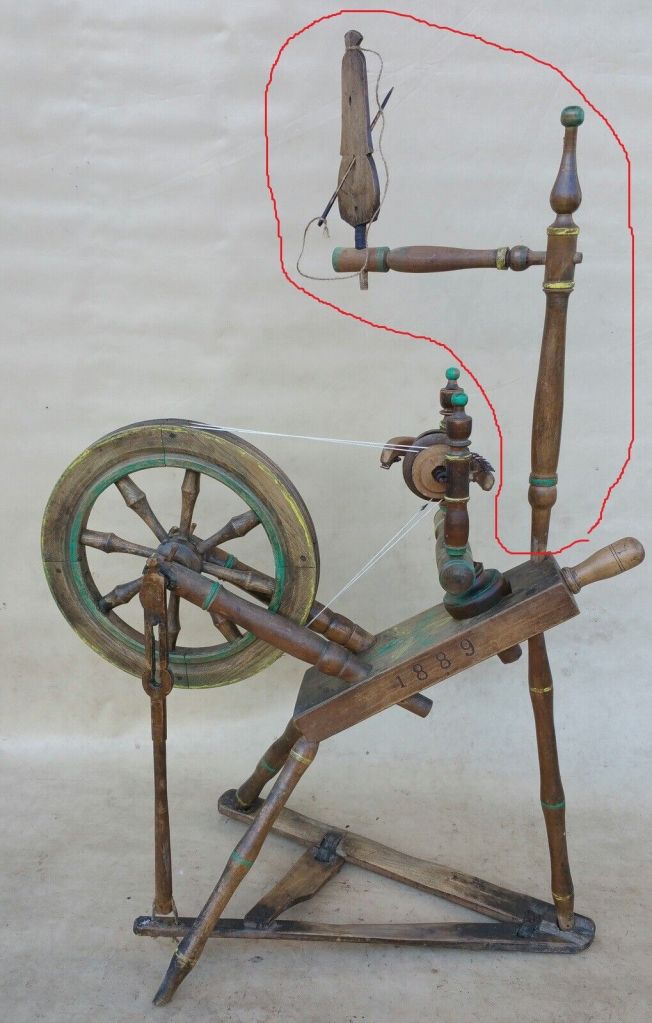

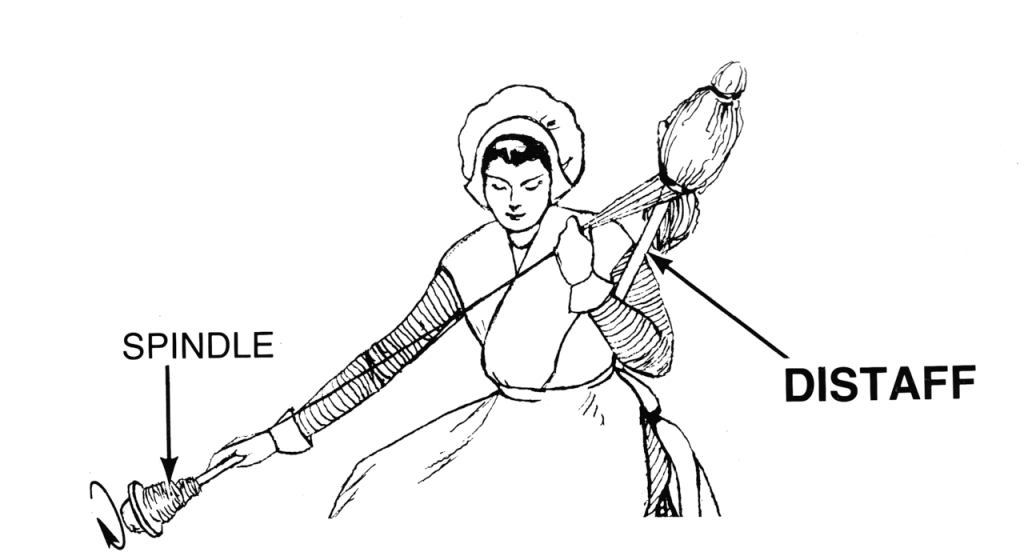

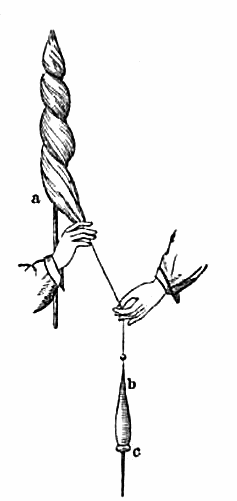

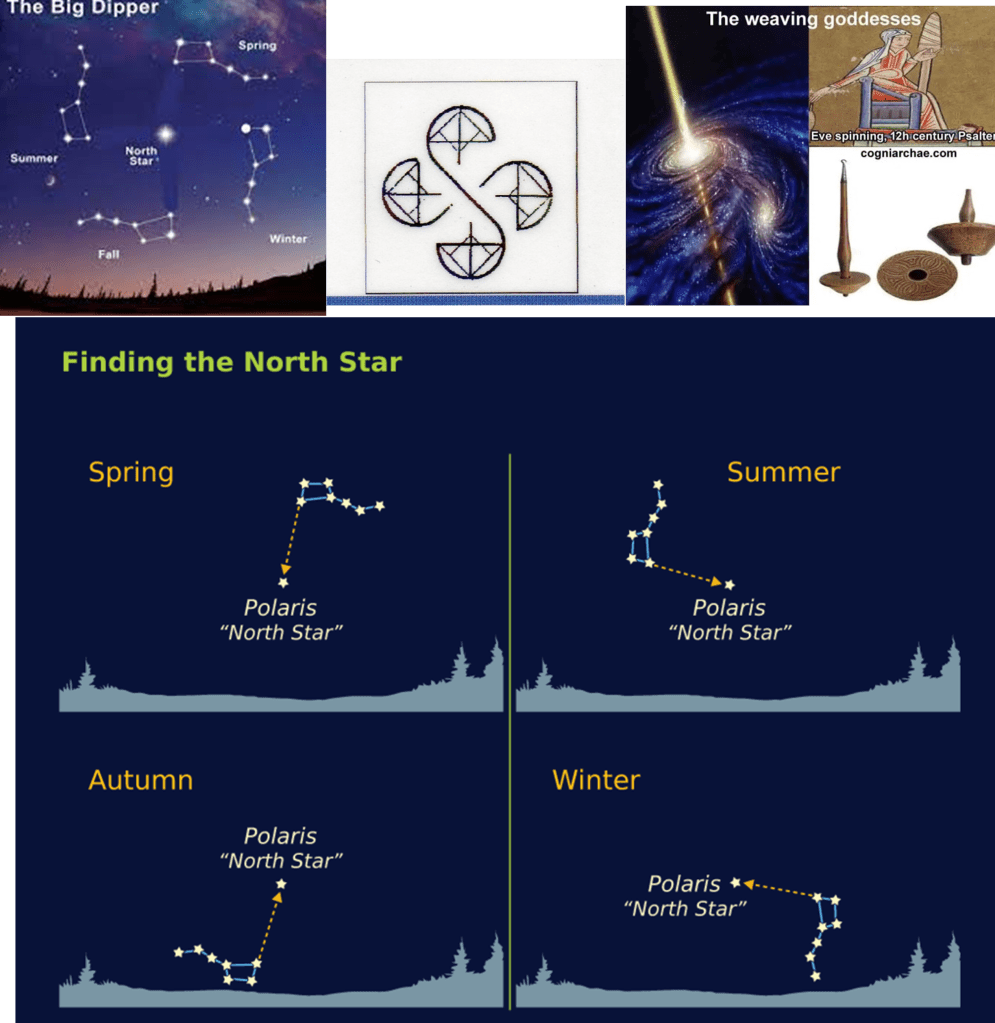

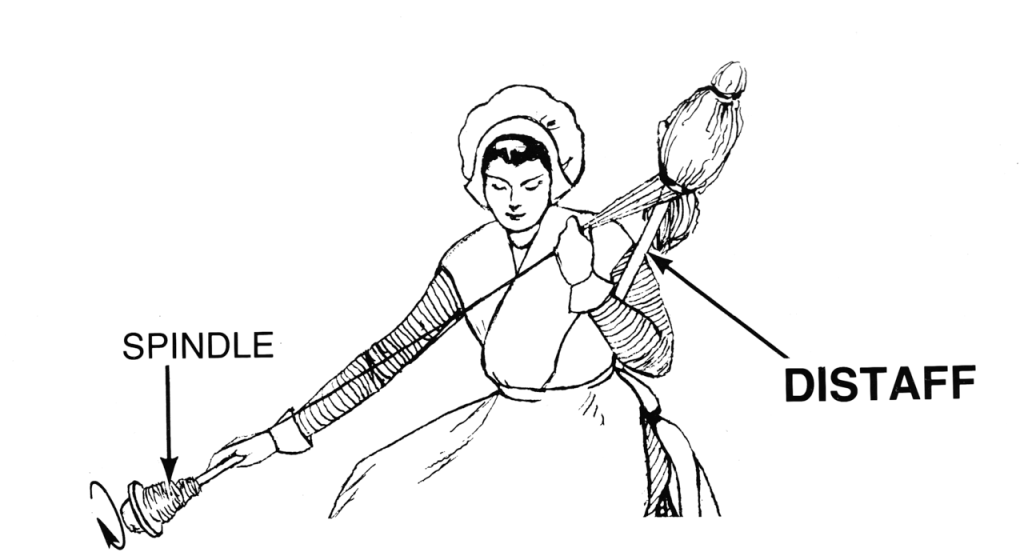

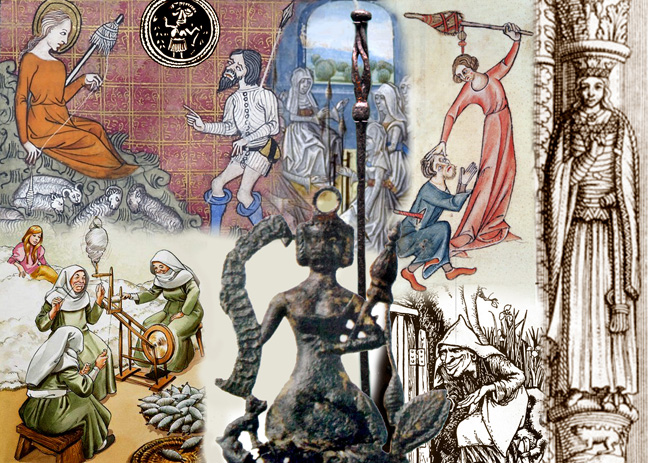

Spinning , Distaff and Frisian Craft

distaff (/ˈdɪstɑːf/, /ˈdɪstæf/, also called a rock[is a tool used in spinning. It is designed to hold the unspun fibers, keeping them untangled and thus easing the spinning process. It is most commonly used to hold flax and sometimes wool, but can be used for any type of fibre. Fiber is wrapped around the distaff and tied in place with a piece of ribbon or string. The word comes from Low German dis, meaning a bunch of flax, connected with staff.

As an adjective, the term distaff is used to describe the female side of a family. The corresponding term for the male side of a family is the “spear” side.

Form

In Western Europe, there were two common forms of distaves, depending on the spinning method. The traditional form is a staff held under one’s arm while using a spindle – see the figure illustration. It is about 3 feet (0.9 m) long, held under the left arm, with the right hand used in drawing the fibres from it.[2] This version is the older of the two, as spindle spinning predates spinning on a wheel.

A distaff can also be mounted as an attachment to a spinning wheel. On a wheel, it is placed next to the bobbin, where it is in easy reach of the spinner. This version is shorter, but otherwise does not differ from the spindle version.

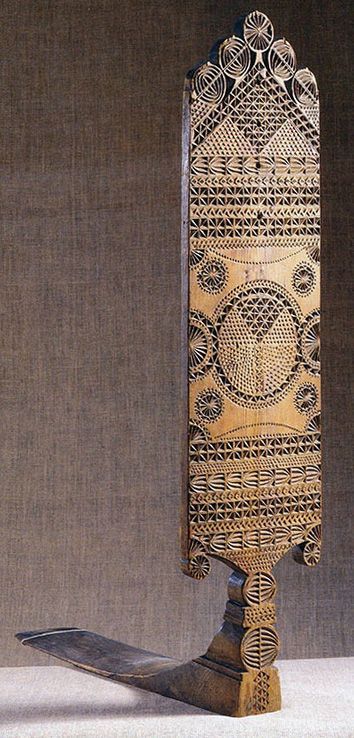

By contrast, the traditional Russian distaff, used both with spinning wheels and with spindles, is L-shaped and consists of a horizontal board, known as the dontse (Russian: донце), and a flat vertical piece, frequently oar-shaped, to the inner side of which the bundle of fibers was tied or pinned. The spinner sat on the dontse, with the vertical piece of the distaff to her left, and drew the fibers out with her left hand. The distaff was often richly carved and painted and was an important element of Russian folk art.[3]

Recently,[when?] handspinners have begun using wrist distaves to hold their fiber; these are made of flexible material, such as braided yarn, and can swing freely from the wrist. A wrist distaff generally consists of a loop with a tail, at the end of which is a tassel, often with beads on each strand. The spinner wraps the roving or tow around the tail and through the loop to keep it out of the way, and to keep it from getting snagged.

Dressing

Dressing a distaff is the act of wrapping the fiber around the distaff. With flax, the wrapping is done by laying the flax fibers down, approximately parallel to each other and the distaff, then carefully rolling the fibers onto the distaff. A ribbon or string is then tied at the top and loosely wrapped around the fibers to keep them in place.

- The millstone and sacred Geometry

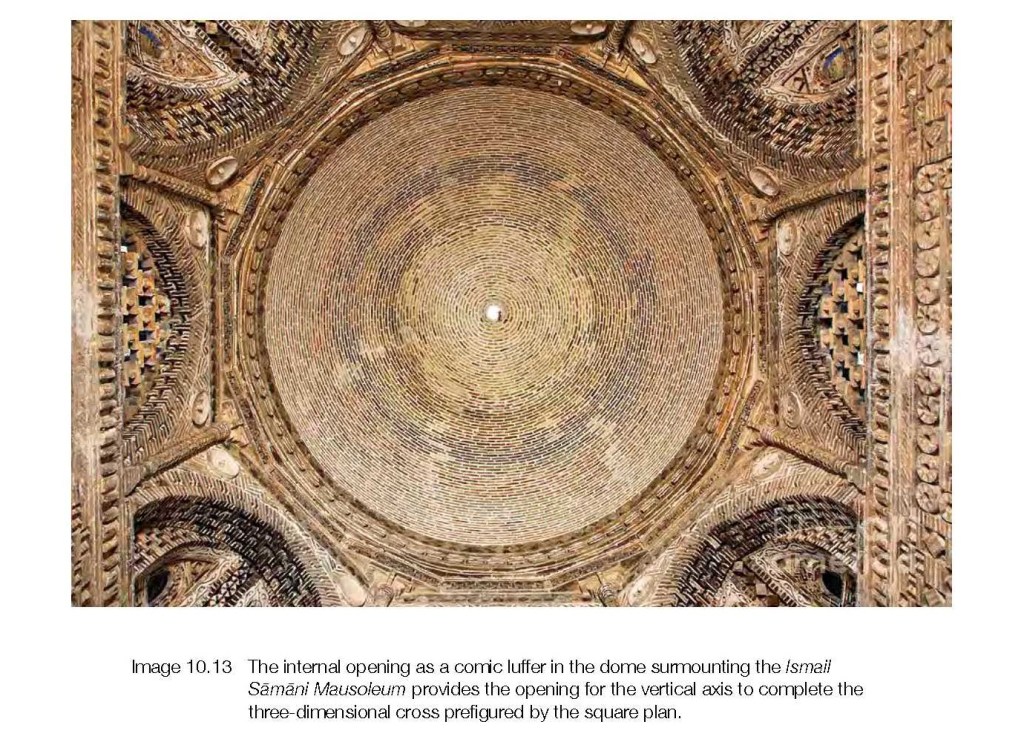

- The cosmogenesis of dwelling: ancient (eco)logical practices of divining the constructed world

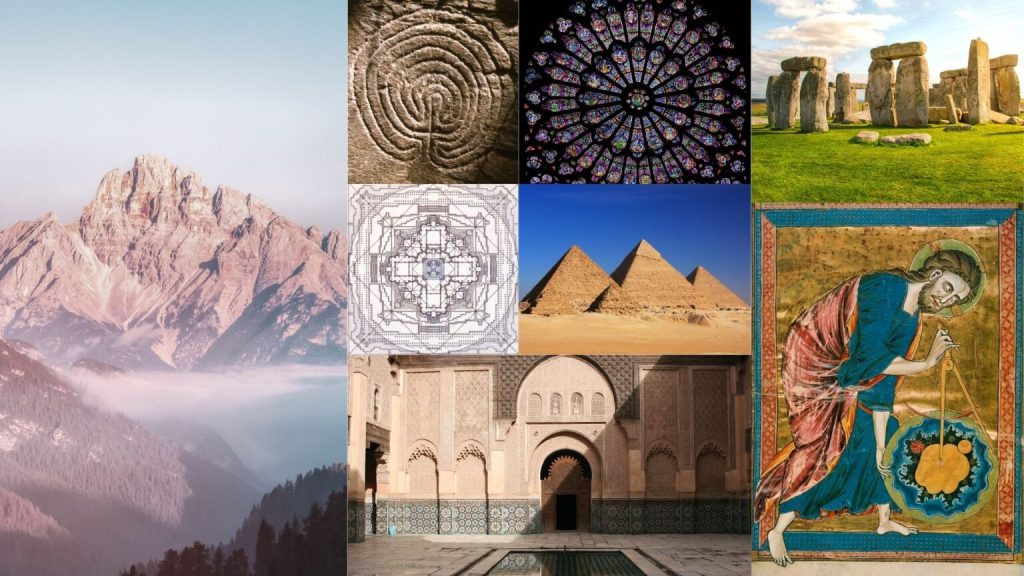

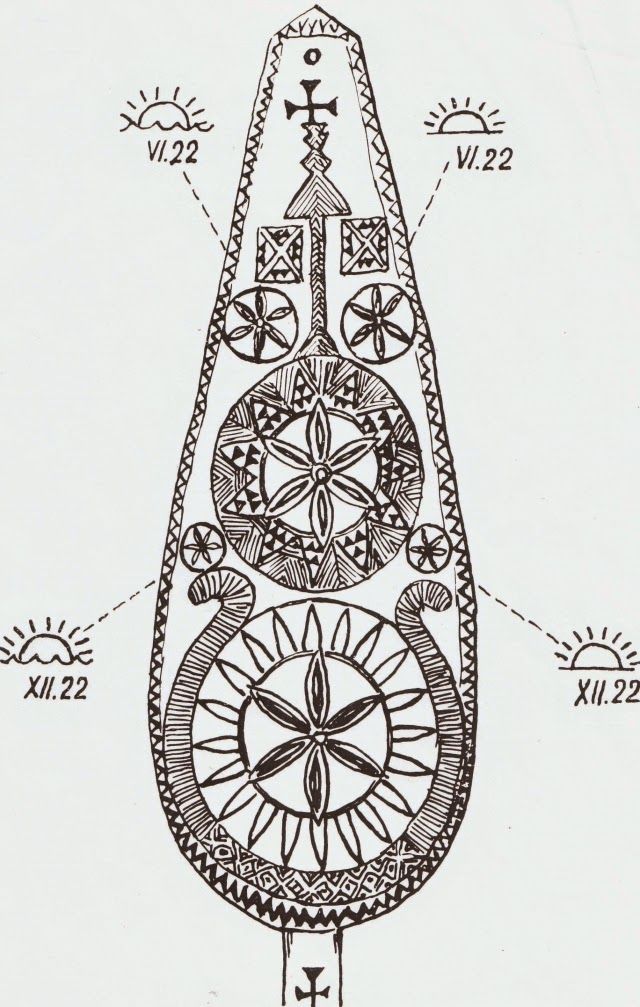

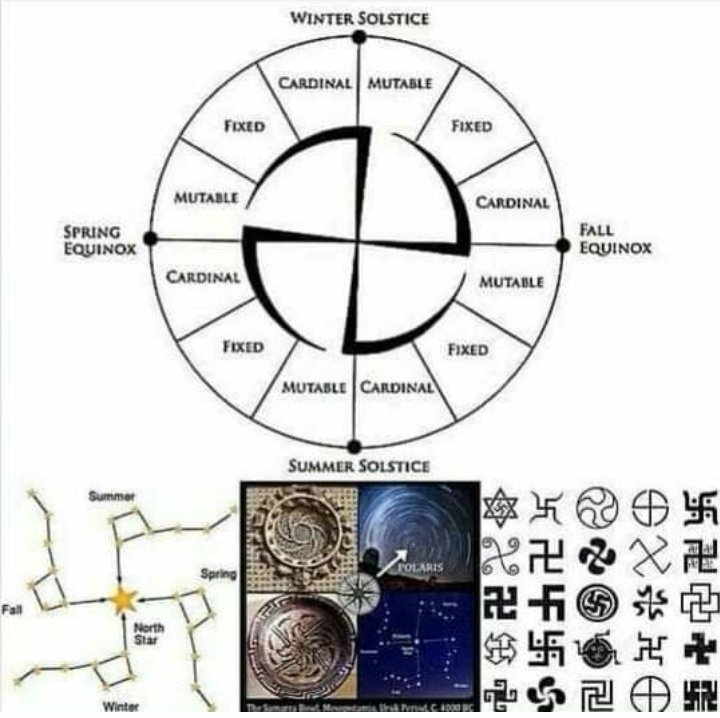

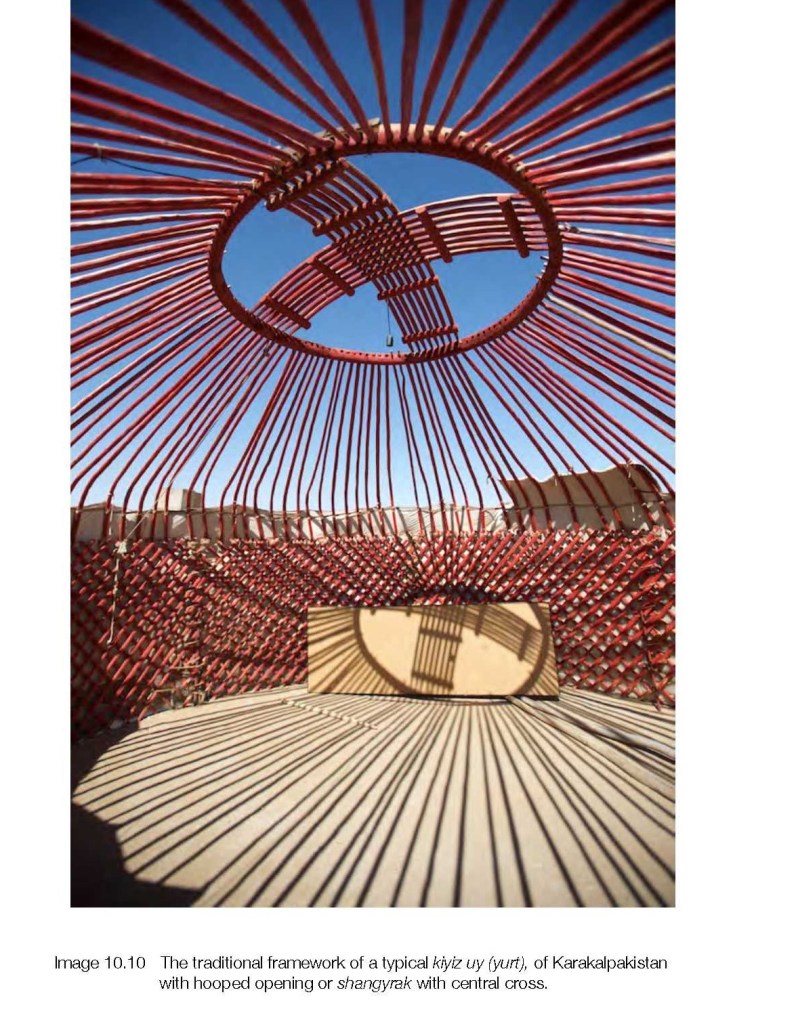

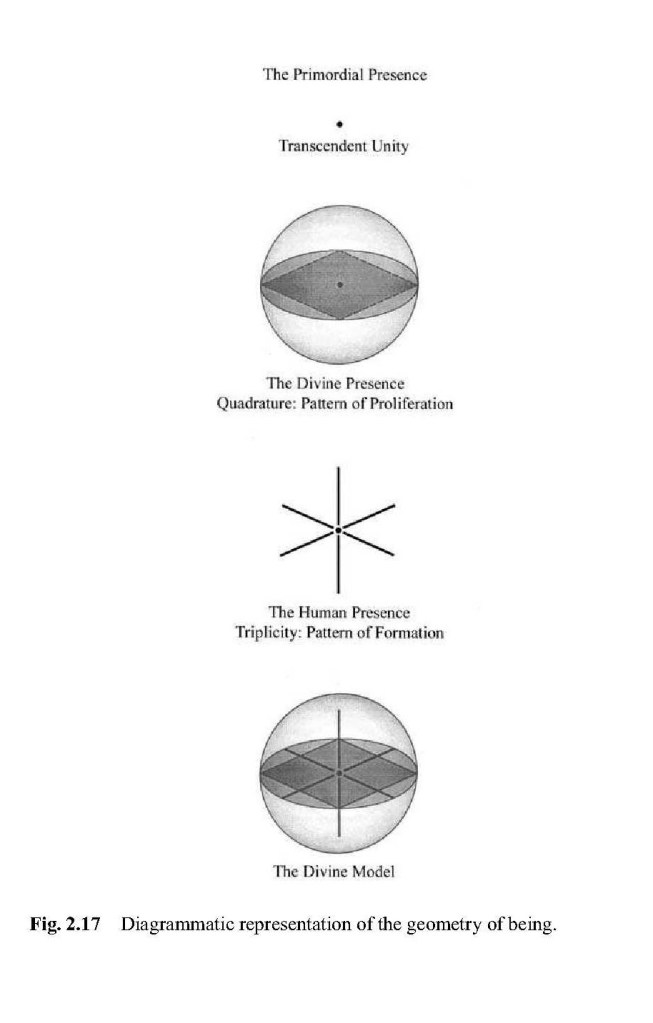

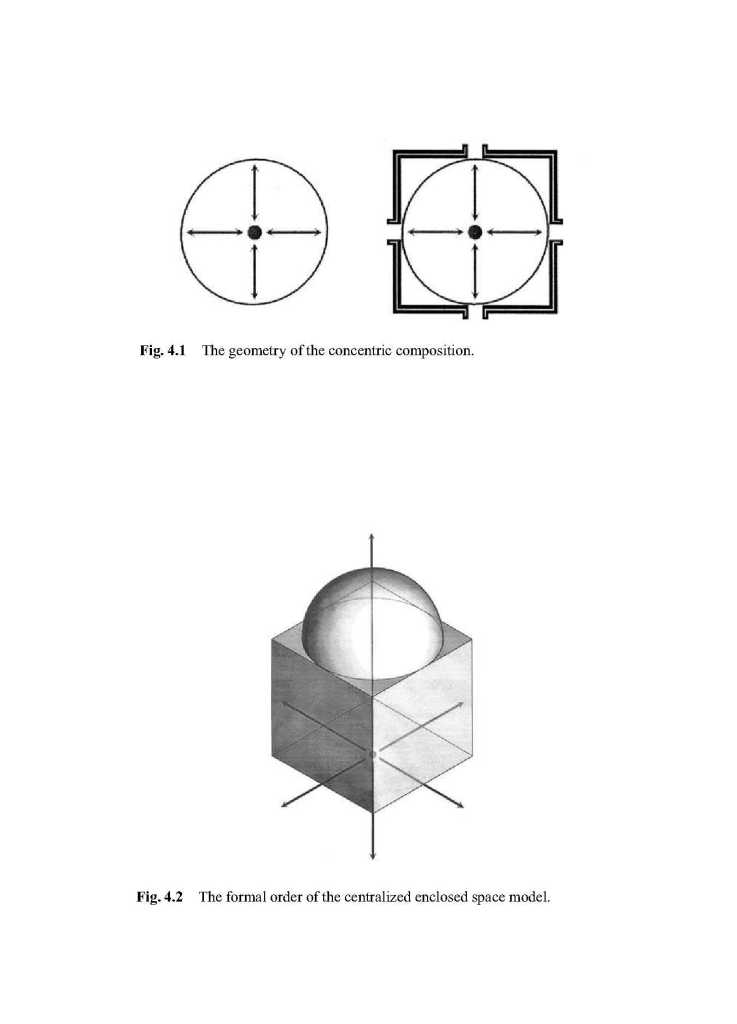

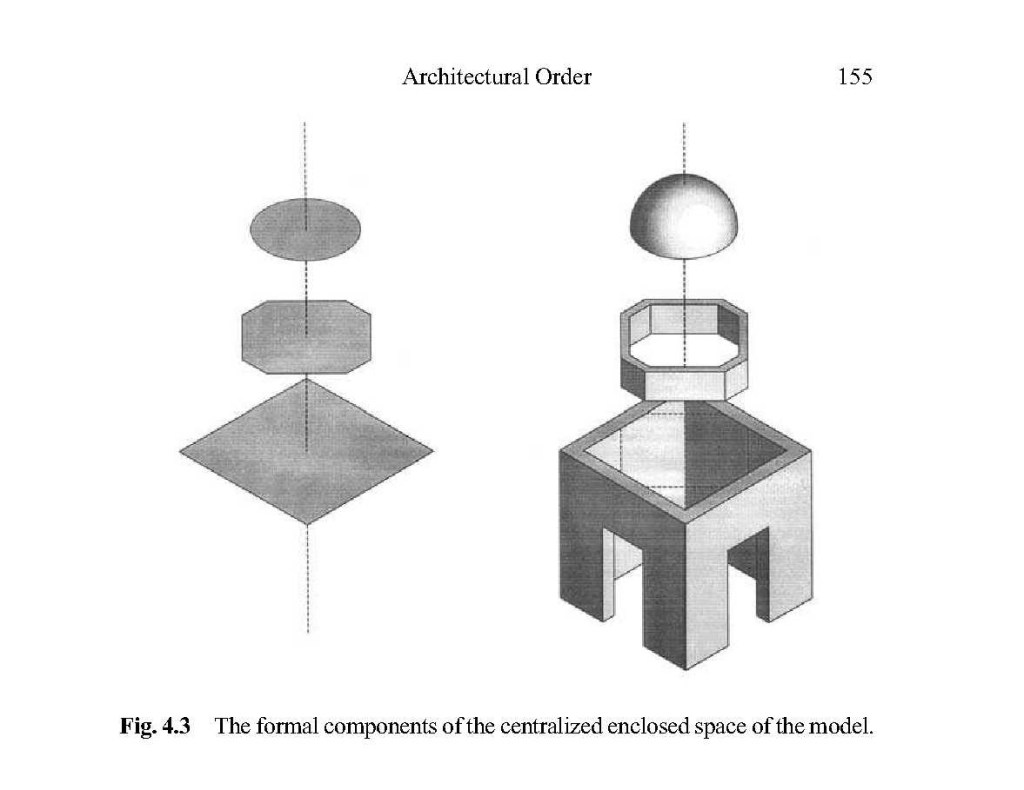

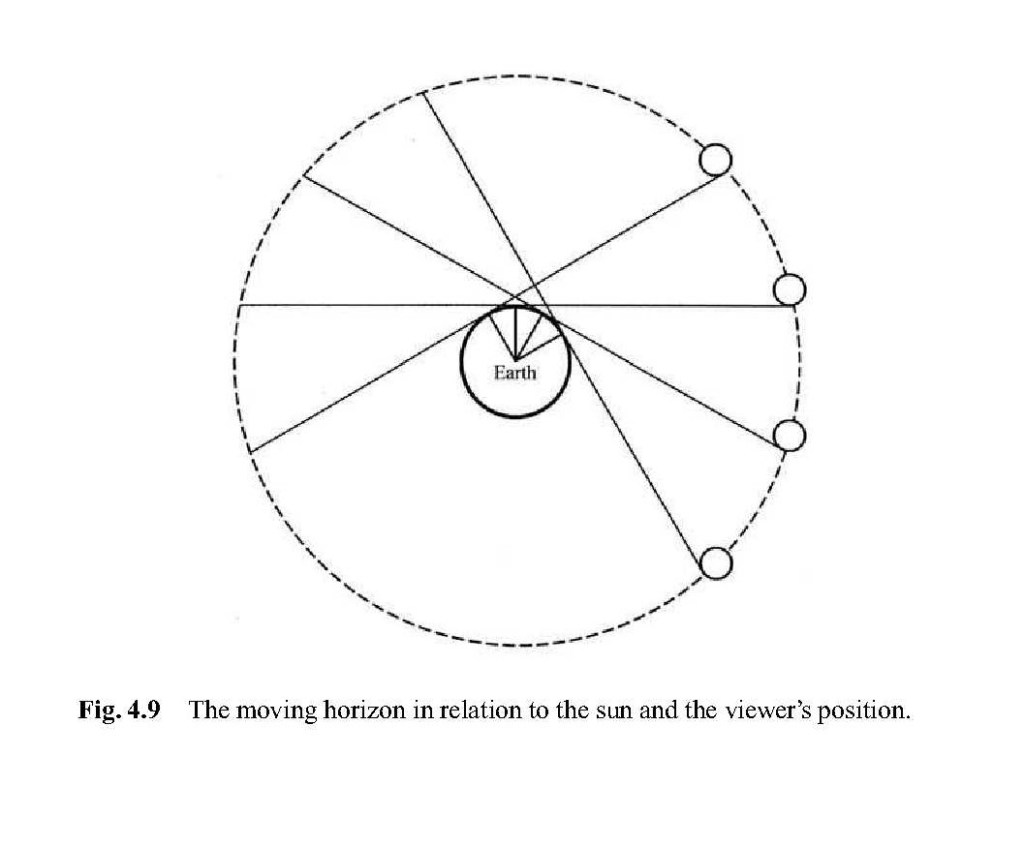

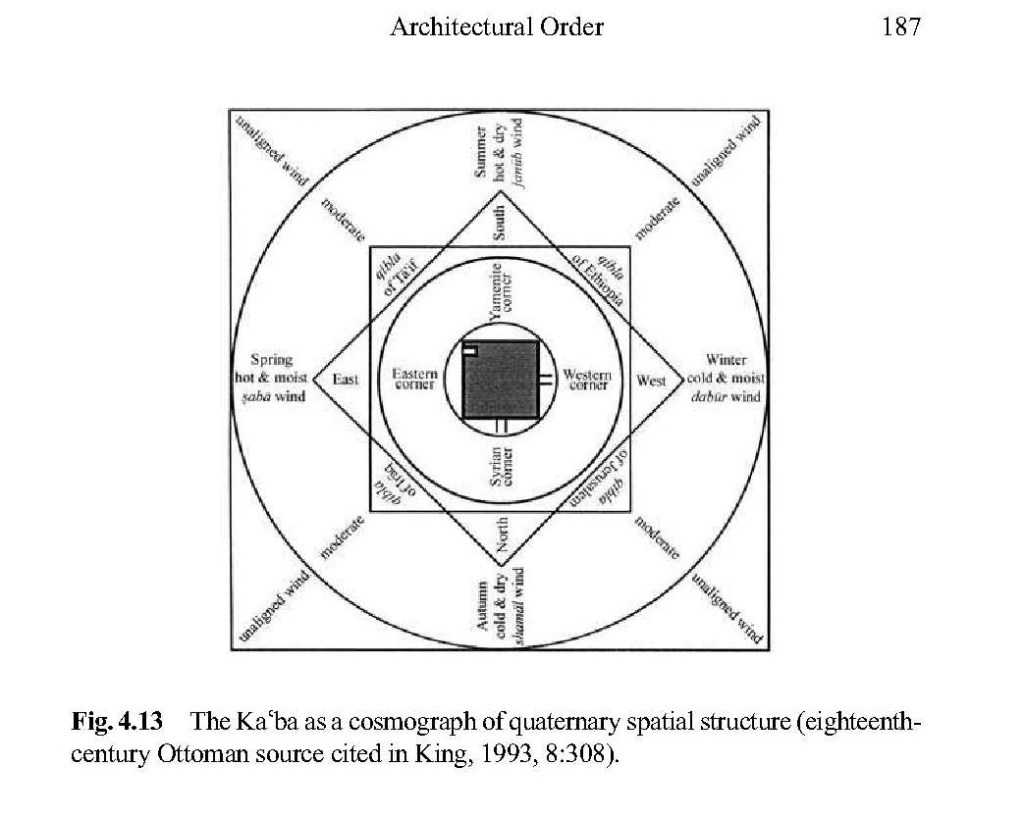

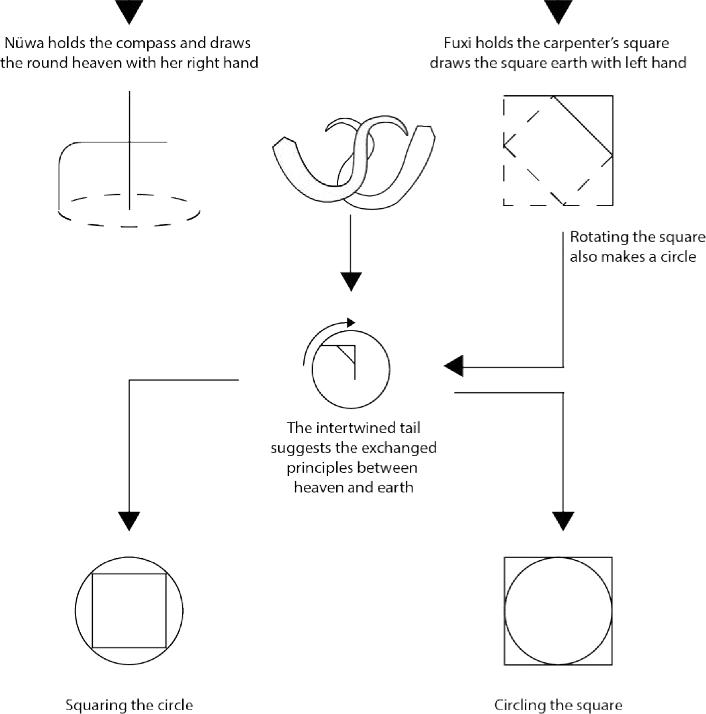

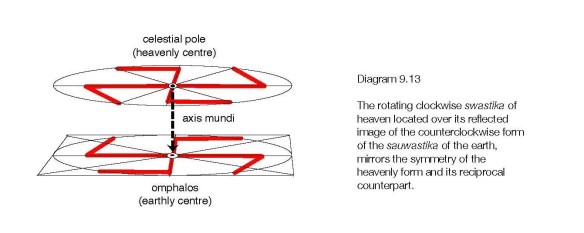

The disenchantment with scientific progress has awakened a new environmental awareness in our culture so that today we are reconsidering the constructed world with respect to the position of the sun to create sustainable environments. This “new” approach to the design of the constructed world is based on ancient traditions that have been lost due to new technologies that have allowed us to defy nature. These ancient traditions were (eco)logical—the forces of nature were used to shape the constructed world to create comfortable dwellings that responded to prevailing environmental conditions. The built world was auspicious because it was oriented towards the cosmos: the positions of the sun, the stars and the planets. Human dwelling was considered to be a microcosm of the universe and was associated with spirituality. The act of building itself was a religious rite. Divining the constructed world was a talismanic operation that the ancients used to orient their earthly creations to be “square with the world” and began with the human body at its center and origin. The cosmological origins of building will be demonstrated by considering the ancient practices of Vāstu Śāstra and Feng Shui as a way of reconsidering present-day body-centered (eco)logical approaches to design.

Divining the Constructed World

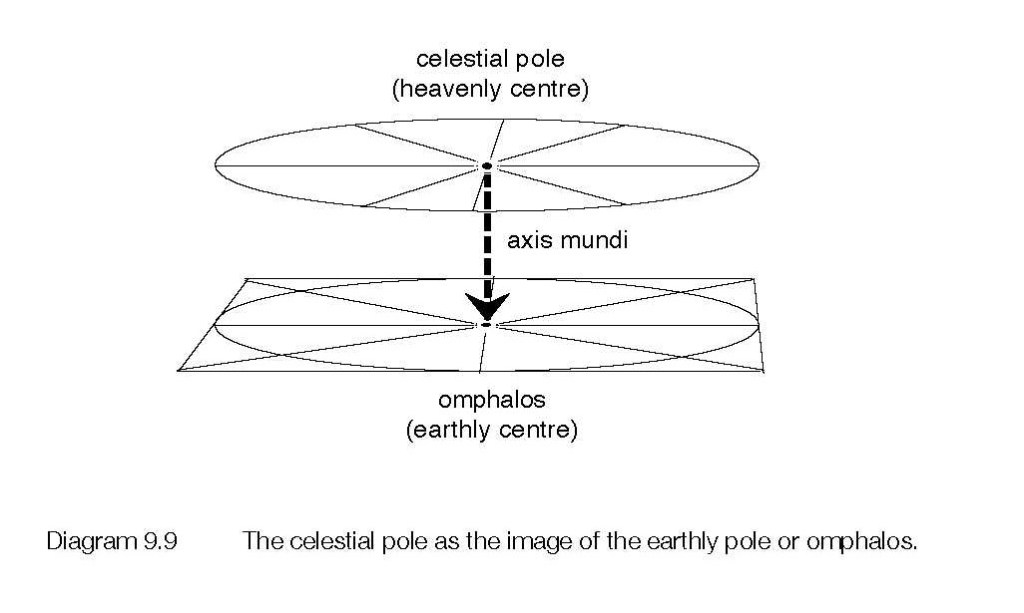

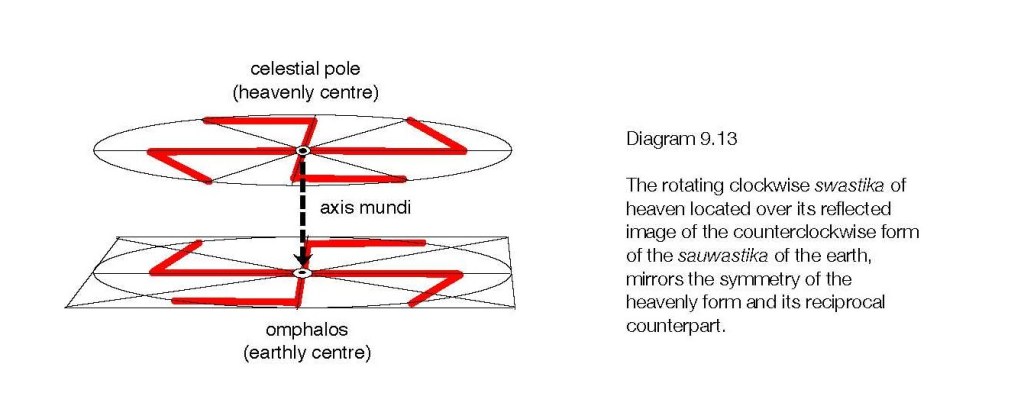

From the trunk of a gum tree Numbakula fashioned the sacred pole (kauwa-auwa) and, after anointing it with blood, climbed it and disappeared into the sky. This pole represents a cosmic axis (axis mundi), for it is around the sacred pole that territory becomes habitable, hence is transformed into a world.

Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane1

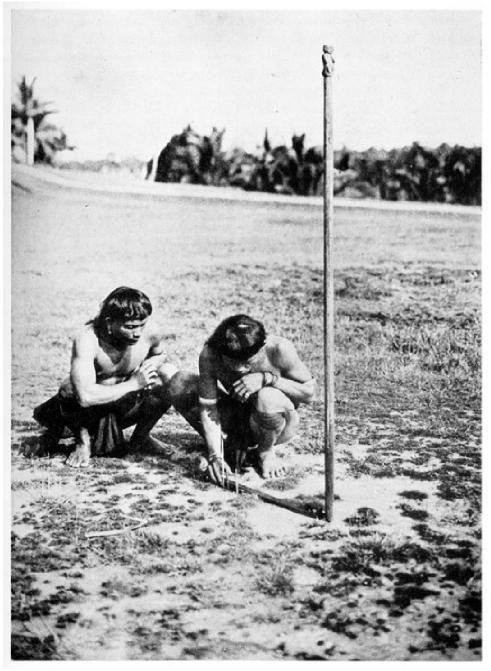

Divining the constructed world was a talismanic operation that the Ancients used to orient their earthly creations to be “square with the world.” The Ancients constructed according to divine co-ördinating principles to align their built works with the cardinal directions of the earth with respect to the cosmos. This was an (eco)logical operation that intended to embody the divine in an earthly construction that began with the human body at its center and origin. The body marked the beginning and the first point of contact with the heavens through its axis mundi, which in the body is the line of the spine in the erect human figure. In this way, the earthly microcosm could be brought into alignment with the macrocosm of the universe.

Divination is a geomantic procedure. The word geomancy is derived from the Greek geo, literally meaning the earth, and manteia, meaning divination or coming from above. Geomancy is the act of projecting lines onto the earth from the cosmos above through marking the ground and encircling. This talismanic operation projects regulating lines upon the ground to provide auspicious conditions for the construction of the built environment and to protect the constructed world. This is a “divine” act with heavenly origins.

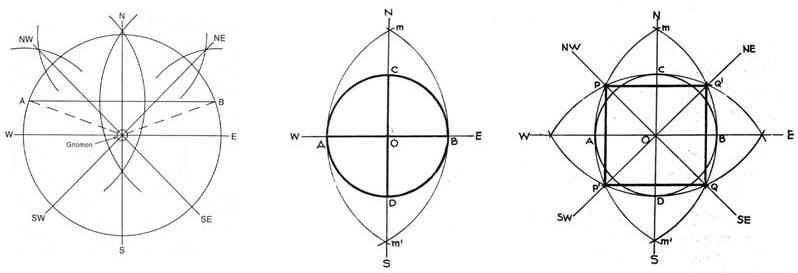

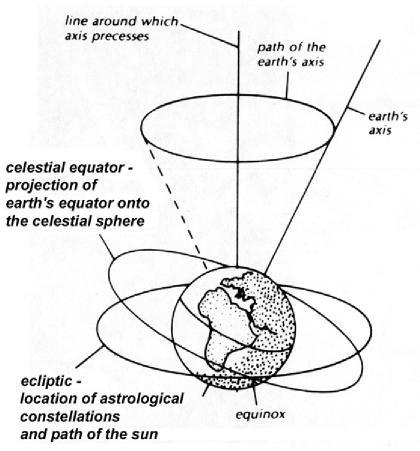

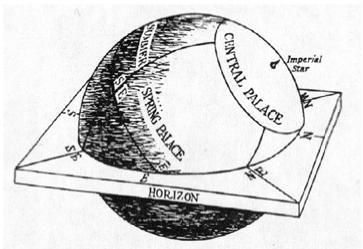

The divine resources for ancient geomantic procedures included the positions and the paths of the sun, the moon, the stars and the planets. The instrument the Ancients used to take their measurements was the gnomon, literally, interpreter. It was a stick, often in the form of a human figure , which was used to help them interpret their position on earth with respect to the greater universe of the cosmos by being encircled: the intersection of the gnomon’s cast shadow and the circle in the morning and the evening at the summer solstice located solar east and west from which north and south could be determined . This (eco)logical procedure resulted in built works that considered the environment through solar and stellar orientation.

- Millstone: The Creation of a New Coalescence Consciousness of Opposites

This study is about the symbolism of Millstone appeared in psychotherapy like sand play therapy with symbol work. Symbols not only deliver meanings but also have numinous power, which produces transformation through powerful energy from emotional experience. Symbols help human’s mentality develop by compromising opposites which cause conflict. This study is to examine the characteristic of Millstone in human history and the symbolic

meaning which appears in mythology and tales and alchemy, and to explain universal and cultural meaning of millstone connected to psychological symbolism. Millstone represents pain through sacrifice of grain, death and the creation of new consciousness as a symbol of the rebirth. Also, it explains the circulation of original nature as a symbol of destiny to overcome by the integration of anima and animus. The millstone described as the symbol of Self in the marriage of mythology represents the coniunctio oppositorum between men and women, a combination of yin and yang. It is the symbol of wholeness integrating conscious and unconscious. Through this study, we consider that millstone is the psychic center of the ego- Self axis and the individuation in the psychotherapy is the process of unceasing transformation of one’s whole personality which experiences the process of balancing, regulating and unifying. Consequently, millstone functions as symbolic intermediation that leads to the center of one’s whole psyche.

Read here

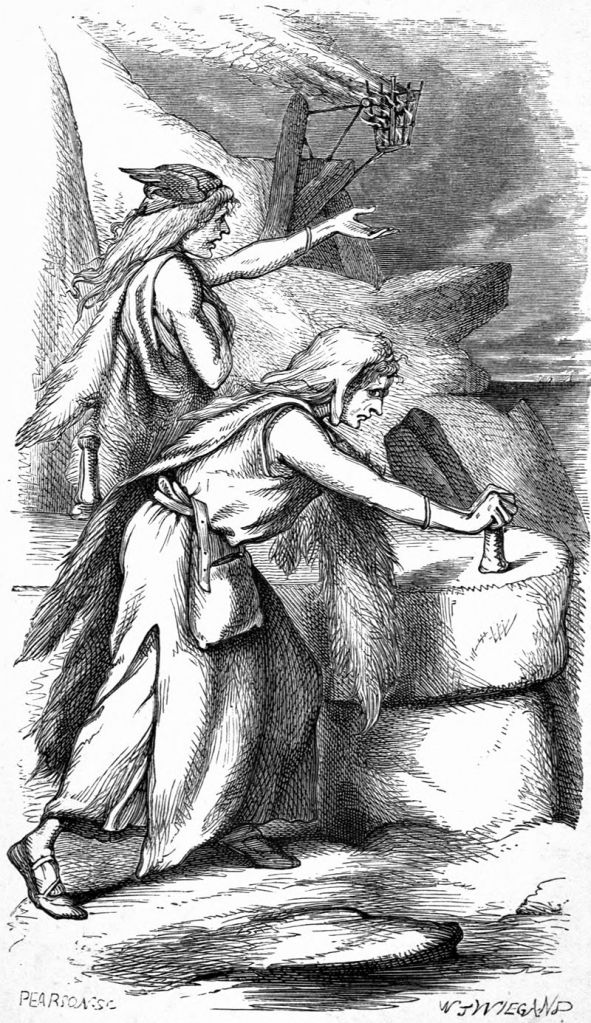

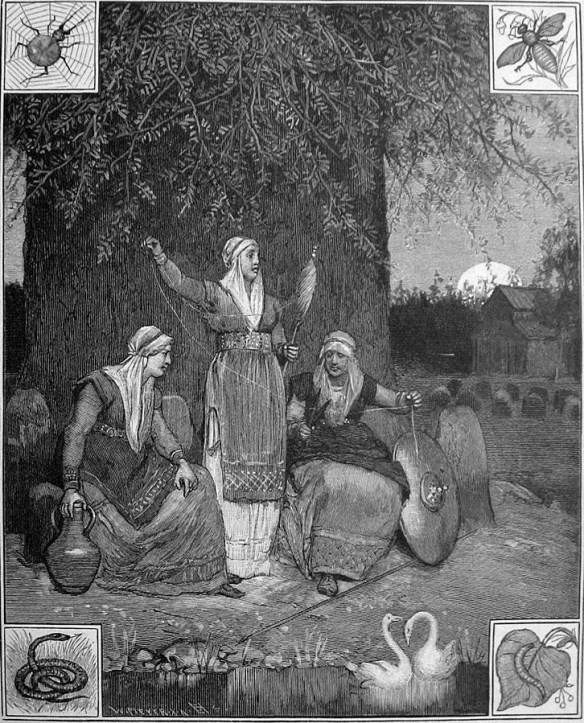

- The Norns and the “Flap aan de wand” table

The Norns, similar to the Fates, they spin the threads of destiny by Yggdrasil, the World Tree. Represent Urd (Past), Verdandi (Present), Skuld (Future). Symbolism: Spinning reflects how past, present, and future are interwoven, shaping all existence

The three Norns or three Fates are maybe forgotten but you can find some presence in Wales in the Castel Coch:

We find back the 3 faces of the three Norns on the back “flap on the wall” table and also their distaffs with the 3 legs of the table:

Distaff Shape: A distaff often has a long, slender, spindle-like appearance with a widened or carved top for holding fibers.

Table Legs Resembling Distaff: Many fold-down or wall-mounted flap tables, especially antique or rustic ones, have legs that are turned (wood-turned on a lathe) into spindle shapes:

The faces of the 3 Norns disappear and became knots but the connection piece is always the same in a wave form of a thread:

- The table legs resemble a distaff, intentionally , it can evoke Aa aesthetic tied to old-world craftsmanship: This resemblance is a practical design choice from woodworking traditions, and it might carry symbolic echoes, especially in cultures where the distaff was a significant household tool.

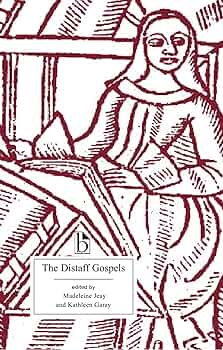

The Diftaff was very special in the Middelages : “Quenouille” is French for distaff, the tool used in spinning to hold fibers, historically associated with women’s domestic work. It was so uimportant that yopu can find an“Évangiles des Quenouilles”, or The Distaff Gospels, it is a 15th-century French collection of popular beliefs, superstitions, and proverbial wisdom, supposedly gathered from women spinning at their distaffs.

Furniture design echoing the distaff can intentionally reference the domestic, female-centered spaces where knowledge, stories, and traditions were passed down — much like the Distaff Gospels themselves. The work presents itself humorously as “gospels” — not religious scripture, but rather the collected “truths” women exchanged while working, often reflecting folk beliefs, moral lessons, and practical advice.

Why “Distaff Gospels“?

In medieval Europe, spinning at the distaff was a communal and domestic female space, where women exchanged stories, advice, and gossip. The title plays on the contrast between sacred religious texts (gospels) and everyday, earthy wisdom passed between women — elevating domestic knowledge in a playful way.

But the most important pice was the front of the table: the Frisian Eternal Knot or Flower of Life. ( see above)

We can call the tables and another crafts a kind of Frisian Folk Mandalas for the daily use of the Family:

- Conclusion

The wisdom of Frisian craft, particularly in clockmaking and other traditional arts from Friesland, reflects deep-rooted values of precision, resilience, respect for tradition, and harmony with nature. Here’s a breakdown of the underlying wisdom embedded in Frisian craftsmanship: Wisdom Reflected in Frisian Craft:

Patience and Precision

Frisian clockmakers were known for their meticulous attention to detail. The delicate mechanisms and ornate decorations took months of steady, focused work, teaching the value of:

Endurance over instant results, Craftsmanship over mass production, Pride in perfecting one’s skill,,Good work cannot be rushed — time is both the master and the measure.

Respect for Time

Frisian clocks, in particular, embody the philosophical relationship with time: Time is cyclical (reflected in moon phases and astronomical elements) – Time governs life, work, and nature’s rhythms – The passing of time demands mindfulness, not haste – The clock reminds owners: Master time, don’t be mastered by it — a reflection of both humility and responsibility.

Connection to Nature

Frisian crafts often incorporate natural elements — woodcarvings, floral designs, or ship motifs — symbolizing: The interconnectedness of humanity and the environment – The rhythm of tides, seasons, and life cycles – Sustainability, using local materials like oak or pine for lasting beauty

Cultural Identity and Storytelling

Frisian craft preserves oral history and regional pride, telling stories through: *Family crests or local symbols on clocks (Scenes of Friesland’s landscapes) in carvings or paintings -* Passing down objects as heirlooms, keeping stories alive across generations – A well-made object carries the soul of its maker and the spirit of its land

Simplicity Meets Elegance

True to Dutch design sensibilities, Frisian craft reflects functional beauty, blending:

Practical engineering (precise clockworks, sturdy furniture) -* Subtle artistry (hand-painted details, symbolic carvings) – Minimal excess, maximum meaning

Legacy of Frisian Wisdom

Even today, the wisdom of Frisian craft is visible in: -Dedication to high standards – Interweaving function with beauty – Honoring tradition while embracing innovation – Living life in harmony with time and nature

Art That Expresses Truth

Ananda Coomaraswamy, deeply rooted in both Eastern and Western traditions, emphasized that the traditional artist or craftsman was not creating to express individuality, but to reveal the timeless:

“The traditional craftsman did not ‘express himself,’ he expressed truths.”

Coomaraswamy rejected the modern cult of originality and innovation. For him, traditional art and craft were “vehicles for eternal wisdom“. The form was not arbitrary—it was a symbolic expression of metaphysical principles, passed down through sacred traditions. Every detail, from proportions to ornamentation, had a purpose that reached beyond aesthetics.

“Work is for the sake of the work done, and not for the profit therefrom.”

In this sense, “work was prayer “—a form of contemplation, a discipline of the soul.

The eternal wisdom formed with Sacred Geometry is universal and is based on the One Truth , “Haqq “in arabic.

- Craft and Tradition: The Sacred Art of Making

In the modern world, craftsmanship is often reduced to technique, productivity, or personal expression. But in the eyes of Traditionalist thinkers like René Guénon, Ananda Coomaraswamy, and Frithjof Schuon, craft is something far more profound—it is a sacred act rooted in metaphysical principles and spiritual symbolism.

Craft as Sacred Knowledge

René Guénon viewed traditional craft not as utilitarian labor but as a means of cosmic participation. The traditional craftsman, for Guénon, was engaged in work that reflected the divine order:

“A craft is not merely a technique, but a transmission of a traditional knowledge, the application of principles that are ultimately metaphysical.”

In traditional civilizations, there was no division between the sacred and the secular in labor. Every craft, from carpentry to stonemasonry, was infused with symbolic meaning. The tools themselves—like the compass, the square, or the chisel—served as metaphors for universal truths. The craftsman, through repeated and intentional action, participated in the divine act of creation.

Work and contemplation were not separate in traditional societies. A craftsman worked not just with his hands but also with an awareness of the symbolic and spiritual meaning of his work.

The tool, the material, and the process had symbolic dimensions. For instance, in masonry or metalwork, the transformation of raw material symbolized the transformation of the soul.

Initiation and Guilds

Guénon emphasized the role of initiatic craft guilds—especially in the West, such as medieval masonry guilds—which preserved esoteric teachings and transmitted initiatic knowledge through symbols, rituals, and oral transmission.

These guilds were structured hierarchically and transmitted cosmological knowledge embedded in tools, geometry, architecture, and ritual.

The compass and square, for example, symbolized heaven and earth or spirit and matter.

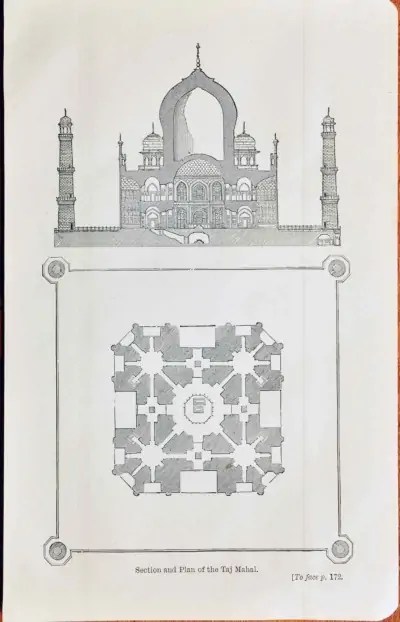

The architecture of temples or cathedrals followed sacred geometry, aligning physical structures with cosmic principles.

Degeneration in Modernity

Guénon argued that in modern times, the loss of sacred and symbolic understanding has led to the degeneration of crafts into mere technical skills, disconnected from their metaphysical roots.

This reflects his larger thesis: modernity is a descent into materialism, fragmentation, and loss of spiritual orientation””. The disappearance of guilds, desacralization of labor, and mass industrialization exemplify this decline.

see:Wisdom of Craftmanship Versus Modernity

- Macrocosmos- Microcosmos

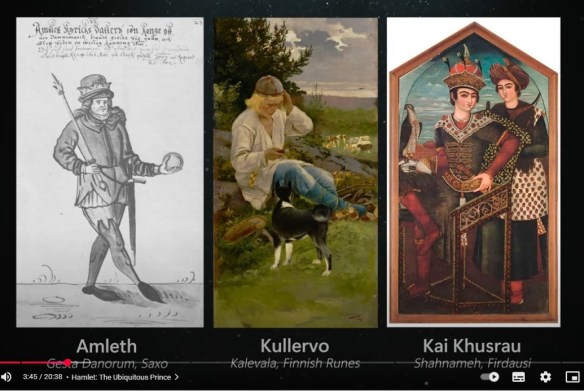

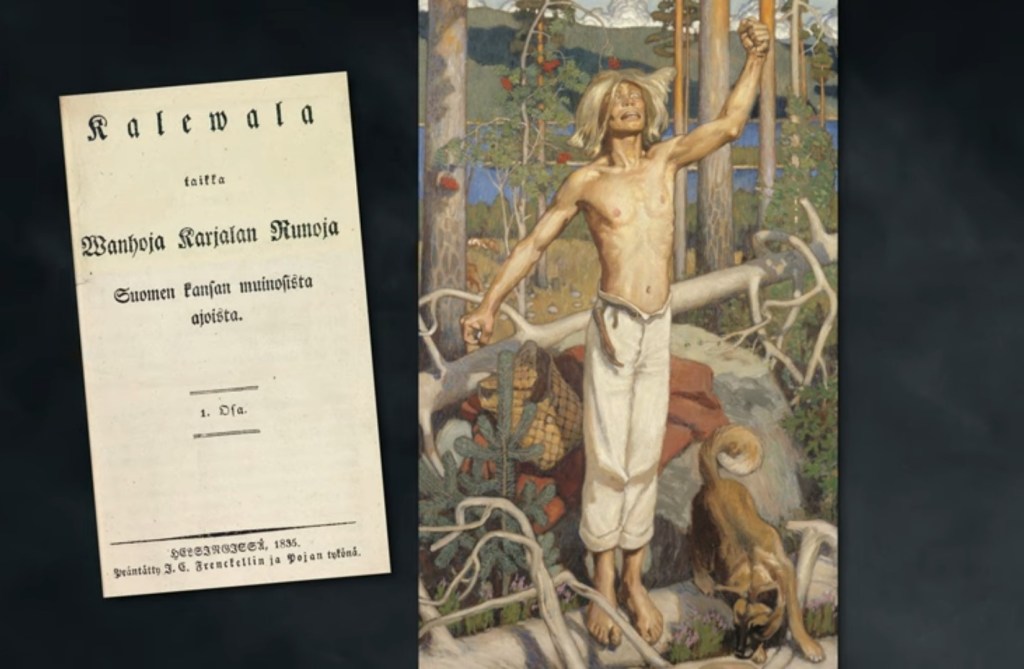

Amleth (Old Norse: Amlóði; Latinized as Amlethus) is a figure in a medieval Scandinavian legend, the direct inspiration of the character of Prince Hamlet, the hero of William Shakespeare’s tragedy Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. The chief authority for the legend of Amleth is Saxo Grammaticus, who devotes to it parts of the third and fourth books of his Gesta Danorum, completed at the beginning of the 13th century.[1] Saxo’s version is supplemented by Latin and vernacular compilations from a much later date. In all versions, prince Amleth (Amblothæ) is the son of Horvendill (Orwendel), king of the Jutes. It has often been assumed that the story is ultimately derived from an Old Icelandic poem, but no such poem has been found; the extant Icelandic versions, known as the Ambales-saga or Amloda-saga, are considerably later than Saxo.2] Amleth’s name is not mentioned in Old-Icelandic regnal lists before Saxo. Only the 15th-century Sagnkrønike from Stockholm may contain some older elements.

– Name

The Old Icelandic form Amlóði is recorded twice in Snorri Sturluson‘s Prose Edda. According to the section Skaldskaparmal,

the expression Amlóða mólu (‘Amlóði’s quern-stone‘) is a kenning for the sea, grinding the skerries to sand.] In a poem by the 10th-century skald Snæbjörn the name of the legendary hero Amlóði is intrinsically connected to the word líðmeldr (‘ale-flower’), leading to the conclusion that the nine mermaids, who operated the “hand-mill of the sea”, “long ago ground the ale-flour of Amlóði”.The association with flour milling and beer brewing, the gold carried around, the net used to catch people and the association with the nine female waves place Amleth on a par with the deity Aegir and his wife Rán.

The late 12th-century Amlethus, Amblothæ may easily be latinizations of the Old Norse name. The etymology of the name is unknown, but there are various suggestions.

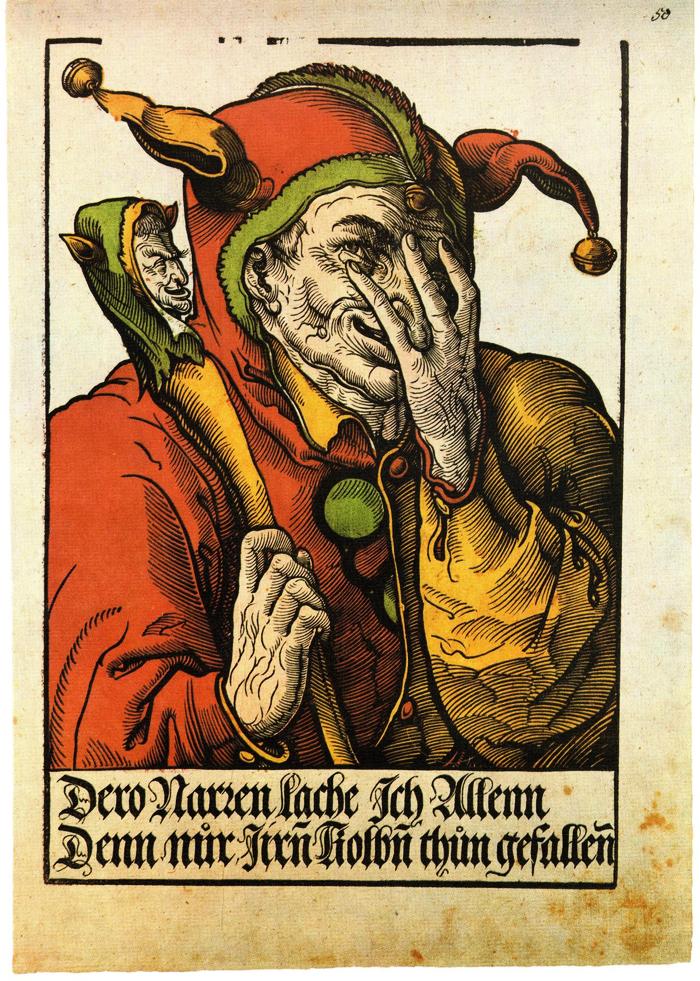

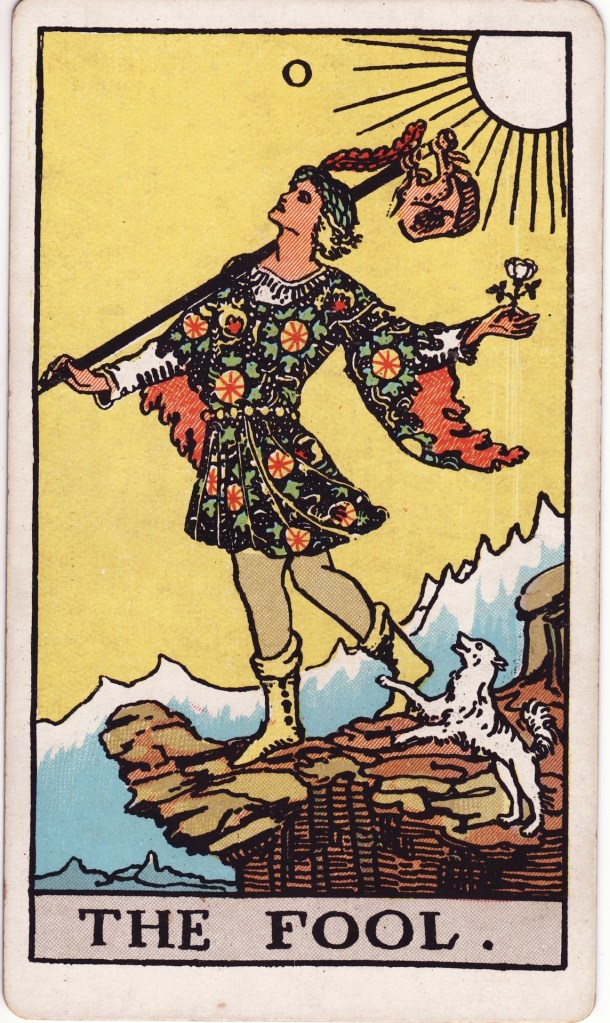

Icelandic Amlóði is recorded as a term for a fool or simpleton in reference to the character of the early modern Icelandic romance or folk tale.[9] One suggestion[10] is based on the “fool” or “trickster” interpretation of the name, composing the name from Old Norse ama “to vex, annoy, molest” and óðr “fierceness, madness” (also in the theonym Odin). The Irish and Scottish word amhlair, which in contemporary vernacular denotes a dull, stupid person, is handed down from the ancient name for a court jester or fool, who entertained the king but also surreptitiously advised him through riddles and antics.

A more recent suggestion is based on the Eddaic kenning associating Amlóði with the mythological mill grótti, and derives it from the Old Irish name Admlithi “great-grinding”, attested in Togail Bruidne Dá Derga.[11]

Attention has also been drawn to the similarity of Amleth to the Irish name Amhladh (variously Amhlaidh, Amhlaigh, Amhlaide), itself a Gaelic adaptation of the Norse name Olaf.[12]

In a controversial suggestion going back to 1937, the sequence æmluþ contained in the 8th-century Old Frisian runic inscription on the Westeremden yew-stick has been interpreted as a reference to “Amleth”.

- Ameland

Ameland is a young island. It is risen from the sea only in the youngest era of geological history of the earth, the Holocene (the geological epoch from 11,700 years ago to the present). The early signs of the origins of the wadden island Ameland came into being after the last ice age. The temperature rose, the icecaps melted, the sea level rose and for our surroundings that meant the North Sea advanced towards the land.

The exact etymology of Ameland is debated, but it likely derives from older Germanic or Frisian roots: “Ame” may come from an old word for water, river, or wetland. “Land” clearly means “land” or “territory” in Dutch and Germanic languages. So, Ameland likely means “land by the water”, river land”, or “wetland area”, which fits geographically since it’s an island surrounded by sea and tidal flats.”

But it is more realistic to say that Ameland come fom Amlodi ,the Old Icelandic form Amlóði is recorded twice in Snorri Sturluson‘s Prose Edda. According to the section Skaldskaparmal, the expression Amlóða mólu (‘Amlóði’s quern-stone‘) is a kenning for the sea, grinding the skerries to sand

- Powerful Jungian symbols: the mill and the bread

In Jungian psychology, symbols hold powerful and often universal significance in the human psyche. The mill, as a symbol, can be interpreted in various ways within this framework. Here are a few potential Jungian interpretations of the symbol of the mill:

The mill can be seen as a symbol of transformation and renewal. Just as a mill grinds grains into flour, it signifies the process of transforming raw or unconscious material into something refined and useful. In Jungian terms, this can represent the journey of individuation, where one moves from a state of unconsciousness to self-awareness and self-realization.

Jung often emphasized the importance of the mandala as a symbol of wholeness and the integration of the self. The circular shape of a millstone or the circular motion of a mill wheel can be likened to a mandala. The mill can represent the journey toward psychological integration and balance.

In Jungian psychology, the anima (the inner feminine aspect in men) and the animus (the inner masculine aspect in women) play significant roles in the individuation process. The mill can symbolize the anima or animus as a guiding force in the process of inner transformation and self-discovery.

The mill could be seen as one such archetype, representing the idea of work, productivity, and the cyclical nature of life — themes that resonate with people across cultures and time periods.The turning of the mill wheel can symbolize the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. Just as the wheel of the mill never stops turning, life also follows a continuous cycle of birth, growth, decay, and renewal.

The process of alchemy, which involves transforming base metals into gold, is a metaphor for spiritual and psychological transformation. The mill, with its grinding and refining process, can symbolize the alchemical journey of turning the “base” aspects of the psyche into something more valuable and enlightened.

The mill as symbol of industriousness

The mill, with its continuous grinding and processing of grain, represents the idea of hard work and diligence. Just as the millstone tirelessly grinds grains into flour, individuals who embrace the symbol of the mill in their psyche may be inclined to value and embody qualities such as persistence, dedication, and a strong work ethic.

In a Jungian sense, the concept of industriousness can extend beyond external work to include inner work and self-improvement. The process of self-discovery and self-realization often requires significant effort and dedication. The mill can symbolize the inner “grinding” and transformation that occurs when one engages in the exploration of the self and works to integrate various aspects of the psyche.

Industriousness is not limited to physical labor but can also encompass creative and intellectual pursuits. The mill’s grinding motion can symbolize the process of generating ideas, creating art, or producing meaningful work. This interpretation emphasizes the idea that industriousness isn’t just about labor but also about the generation of valuable output.

The mill’s cyclical motion, as it continually turns the wheel, can represent the cyclical nature of industriousness and productivity. It highlights the idea that effort and hard work are ongoing processes, much like the seasons or the passage of time. This cyclical nature can also symbolize the need for balance between work and rest.

The act of grinding grains to make flour carries rich symbolic significance, often associated with themes beyond its literal meaning. Here are some interpretations of the symbol of grinding for making flour:

Grinding grains into flour is a transformative process. The symbol can represent the idea of transformation in general, where something raw or unrefined is processed and refined into a more valuable and useful form. This can be applied to personal growth and development, where individuals work on themselves to become better versions of themselves.

Just as grains are ground to make flour, individuals may go through difficult experiences that shape and refine their character. This symbol can be a reminder that personal growth often involves facing and overcoming challenges.

The act of grinding can be physically demanding and may involve suffering. In a symbolic context, it can represent the idea of enduring suffering or hardship for a greater purpose. This connects to the idea that meaningful achievements often come with sacrifices and challenges.It can also represent the qualities of patience and persistence. Just as the millstone keeps turning, individuals may need to persevere through long and arduous journeys in life to achieve their goals.

The process of grinding can also symbolize the importance of balance and moderation. Too much grinding can reduce grains to dust, while too little can leave them unprocessed. This can be a reminder to find a balance in life’s endeavors and not to overexert or neglect important aspects of one’s life.

Incorporating the symbol of grinding for making flour into storytelling or personal reflection can add depth to the narrative and offer insights into themes of transformation, personal growth, endurance, and balance. It serves as a reminder that even mundane tasks can hold profound symbolic meaning.

The symbols of the flour and the bread

Bread is a rich and universal symbol that holds various meanings across cultures and throughout history. Here are some common symbolic interpretations of bread:

Bread is often seen as a symbol of basic sustenance and nourishment. It represents the fundamental sustenance needed for physical survival. In a broader sense, it can also symbolize the emotional and spiritual nourishment required for a fulfilling life.

In many cultures Bread has historically been a staple food shared among people, symbolizing communal bonds, sharing, and hospitality. Breaking bread with others often signifies unity and the sharing of resources, both material and emotional. Also, in some cultures and religious traditions, bread is used as an offering or sacrifice to deities or spirits. It represents a gesture of devotion and giving back.

Bread’s association with grains and the cycle of planting, harvesting, and grinding gives it a connection to the cycles of life and fertility. It can represent the cycle of birth, growth, and renewal.

In many religions, bread plays a central role in rituals and symbolism. In Christianity, for example, the Eucharist or Holy Communion involves the consumption of bread as a representation of the body of Christ. In this context, bread symbolizes spiritual nourishment and connection with the divine.

From an alchemical perspective, bread is the result of a transformational process involving the mixing and fermentation of ingredients. This can symbolize the transformative power of time and effort in turning raw materials into something more valuable and nourishing. It can also be seen as a metaphor for inner transformation and personal growth.

As a basic food staple, bread is often associated with abundance and prosperity. It can symbolize the fulfillment of material needs and the rewards of hard work and productivity.

The process of making bread involves combining separate ingredients into a cohesive whole. This can symbolize the idea of unity and oneness, where different elements come together to create something greater than the sum of its parts.

Bread, with its simple ingredients of flour, water, and yeast, can symbolize humility and the value of simplicity in life. It reminds individuals to appreciate the simple pleasures and necessities of life.

The symbolic meanings of mills, grinding, and bread are versatile and often depend on cultural, religious, and personal contexts. They are powerful symbols that resonate with many aspects of human experience, from physical sustenance to spiritual and emotional fulfillment.

– Thread-Spirit: The Symbolism of Knotting and the Fiber Arts

Written after years of studying both the textile arts and traditional symbolism, The Thread-Spirit is a compendium of the wisdom of both essential human exercises. Inasmuch as we express who we are through what we create and use, through our technologies, we are the human beings described in this book.

The technology of traditional societies is based on the application of metaphysical principles to practical ends. This is particularly clear in the case of the fiber arts— knotting, weaving, spinning, basketry, and the like—where a worldwide symbolism exists which appears to have its origins in Paleolithic times.

There is an underlying historical continuity to this symbolism that survives, but has been forced underground with the rise of rationalism. These traditions survived into the 20th century in more remote parts of the world, but they were generally no longer understood. The Thread-Spirit attempts to examine the traditions, as they existed and continue to exist, and reunite them with their ancient meanings.

The technology of traditional societies is based on the application of metaphysical principles to practical ends. This is particularly clear in the case of the fiber arts— knotting, weaving, spinning, basketry, and the like—where a worldwide symbolism exists which appears to have its origins in Paleolithic times. Dr. A. K. Coomaraswamy referred to this symbolic complex as the sutratman (thread-spirit) doctrine and it is well documented by the literary, artistic and archeological remains.

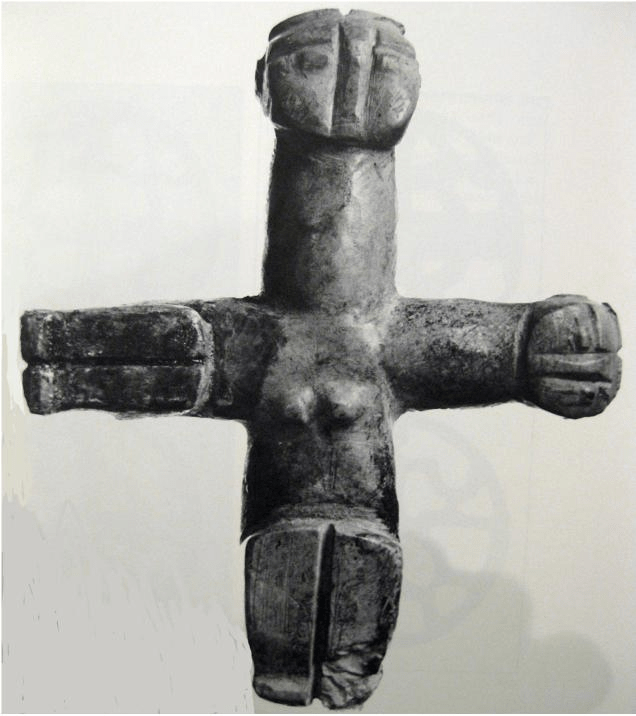

Using a consistent set of symbols, our ancient ancestors sought to explain the relations governing the social order, the workings of the cosmos, and the mysteries surrounding birth and rebirth. The eye of the needle, for example, was understood as the entrance to heaven while the thread was the Spirit that sought to return to its Source. Creation is a kind of sewing in this version of the story as God wields his solar, pneumatic needle. Man is conceived as a jointed creature similar to a marionette or puppet but held together by an invisible thread-spirit. When this thread is cut, a man dies, comes “unstrung,” and his bones separate at the joints.

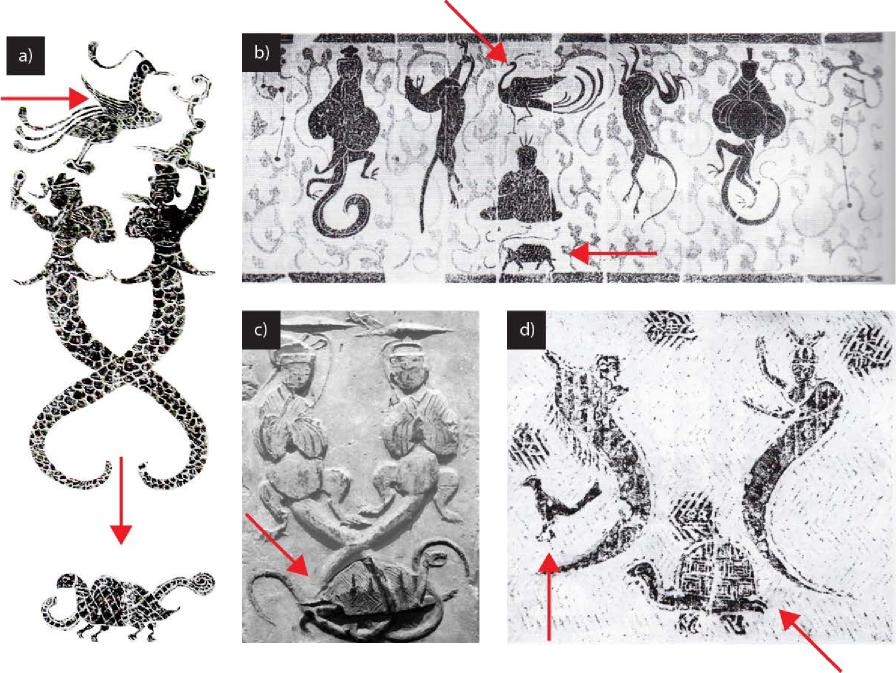

It was the American art historian, Carl Schuster who first discovered the significance of body joints in this symbolism and he believed that it was based on an analogy with the plant world where regeneration is possible from a shoot or sprout. Body joints play a role in such diverse matters as labyrinths, continuous-line drawings, cat’s cradles, dismemberment and cannibalism, and various rituals meant to ensure rebirth and the continuity of the social order. Read here :The Thread-Spirit Doctrine:An Ancient Metaphor in Religion and Metaphysics with Prehistoric Roots

– Lo-Shu , the labyrinth and the Tortoise

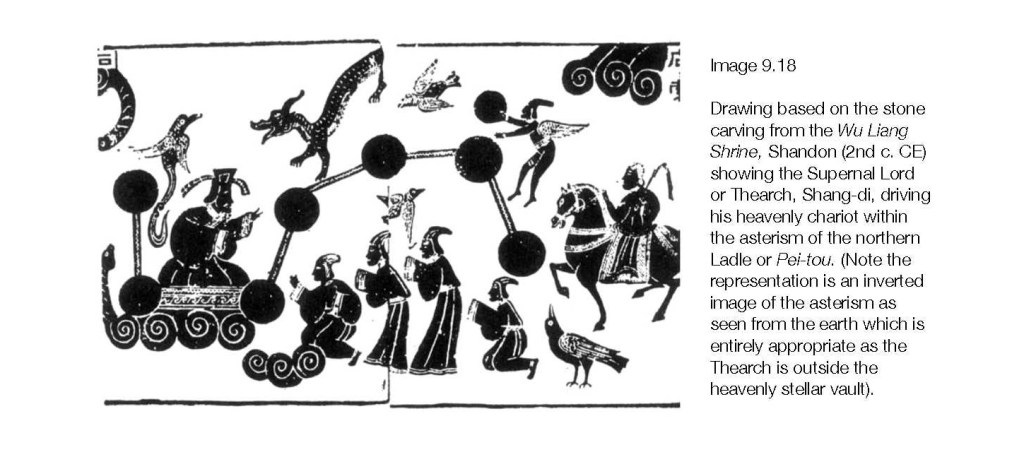

A journey from the primordial China of the legendary rulers to the maze of the palace of Knossos to the sovereignty of Saturn, in an attempt to unravel a plot which – like a dance – turns out to be based on rules animated by a lost science of rhythm whose vestiges are manifested in diagrams cosmological information informed by the observation of the highest heaven: the circumpolar region as it must have appeared in 3000 BC, different from the current one due to the precessional cycle.

We do not know how the original concept of the labyrinth, probably Minoan, was born. In any case, it was more concrete than the Greek references cited indicate, because the definition of “remarkable (stone) structure” sounds derivative and vaguely metaphorical. It is conceivable that the name of a certain structure attributed to Daedalus became a generic designation — as happened, for example, with the proper name “Caesar,” which came to mean the epitome of sovereign power and rank, as reflected in the German word “Kaiser” and the Russian word “tsar”.[1]

Kern thinks it more likely that the primary use of the word was related to a dance, whose pattern would “crystallize” much later in permanent forms, such as graffiti, petroglyphs and – finally – built structures. However plausible it may seem, this hypothesis does not shed much light on the first meaning of this drawing and on the reasons for its established form, the one we usually refer to as Cretan o knossian. Nor does it explain why such an important “structure” as a king’s palace should have the shape of a dance path.

While it is true that a Latin given name such as Caesar has come to mean “the epitome of sovereign power and rank”, on the other hand we may find that the English word King and the German one King may share a common root with the word having the same meaning in the Turkic and Mongolian languages: Khan

see Lo-Shu , the labyrinth and the Tortoise

And THE METAPHYSICAL SYMBOLISM OF THE CHINESE TORTOISE

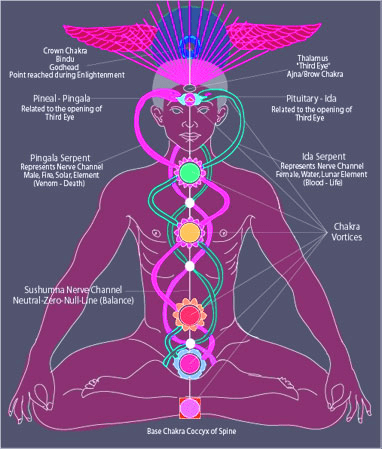

- THE KUNDALINI – SERPENTS AND DRAGONS

The Kundalini refers to the dormant power or energy present in every human being, and lying like a coiled serpent in the etheric body at the base of the spine. This coiled serpent has been biding its time for ages, waiting for the day when the soul would begin to take charge of its rightful domain—the personality, or the combination of the physical, astral and mental bodies.

This ‘spiritual’ force, while still asleep, is the static form of creative energy which serves to vitalise the whole body. When awakened and beginning to ‘uncoil’, this electric, fiery force proves to be of a spiral nature, and hence the symbolic description of ‘serpent power’.

As the Kundalini force is aroused, it will steadily increase the vibratory action of the etheric centres and consequently also that of the physical, astral and mental bodies through which the vital body finds expression. This animating activity will have a dual effect, firstly by eliminating all that is coarse and unsuitable from the lower vehicles, and secondly by absorbing into its sphere of influence those lofty qualities which will serve to raise the energy content of the vital body of the evolving individual. Read more here.

See the Sacred Geometry of plants and The Geometry of Flowers

For more info about The Frisians Look at

Frisia Coast Trail

Salt Samphire & Storytellers

anglo-saxons animals archaeology battles & war business men Celts Cologne drowned lands dykes fashion & lifestyle floods freedom Frisians hiking history kings legends money mud names Old Frisian Law paganism peat piracy religion & spiritual Rhine Romans runes saints salt marsh Seven Sealands sports tax terp travels Vikings værft Wadden Sea Warft wierde women

————————————————————————————————

The Mill, The Stone and The Water

by Rumi

All our desire is a grain of wheat.

Our whole personality is the milling-building.

But this mill grinds without knowing about it.

The millstone is your heavy body.

What makes the stone turn is your thought-river.

The stone says: I don’t know why we do all this,

but the river has knowledge!

If you ask the river, it says,

I don’t know why I flow.

All I know is that a human opened the gate!

And if you ask the person, he says:

All I know, oh gobbler of bread, is that if this stone

stops going around there will be no bread for your bread-soup!

All this grinding goes on, and no one has any knowledge!

So just be quiet, and one day turn

to God and say: “What is this about bread-making?”