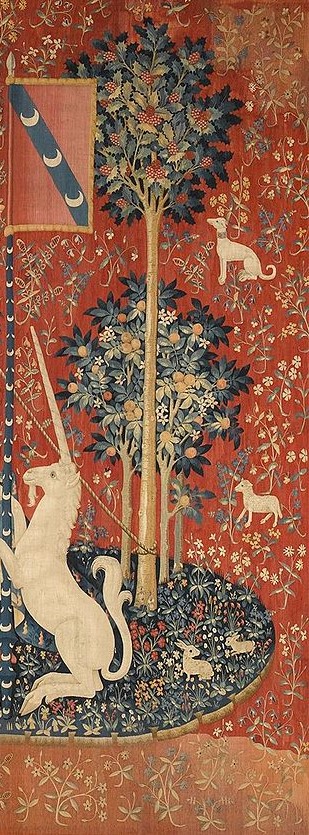

The fame of the tapestry series entitled “The Lady with the Unicorn” comes both from the simplicity of its composition and the depth of its mystery. The charm of the Lady and young Lady accompanying her, the placidity of the mythical, exotic and familiar animals, the background decorated with trees bearing fruit and thousand of spring flowers give the impression of a poetic world imbued with strong sense of serenity.

The fame of the tapestry series entitled “The Lady with the Unicorn” comes both from the simplicity of its composition and the depth of its mystery. The charm of the Lady and young Lady accompanying her, the placidity of the mythical, exotic and familiar animals, the background decorated with trees bearing fruit and thousand of spring flowers give the impression of a poetic world imbued with strong sense of serenity.

The whole set was created at the end of the 15th or the beginning of the 16th century, probably at the request of a nobility family, the coat of arms of which can be found on each of the tapestries. The creation and realization were probably entrusted to a workshop from the Master of Anne of Brittany. After an eventful journey, the six tapestries ended up in 1882 in the Museum of Cluny in Paris. The relationship between five of the tapestries and the five senses, by A.F. Kendrick in 1921, has notably improved the comprehension of the series. The last tapestry, entitled “My sole desire”, was interpreted as a “sixth sense” and gave rise to many commentaries. This “sixth sense” is usually interpreted as a “sensitive intuition” that lets us “feel” things.

The tapestries are presented in a sequence in accordance with the medieval hierarchy of the five senses. The sense hierarchy the most frequently seen in the texts from that time is based on their more or less proximity with the soul. That is in increasing order: Touch, Taste, Smell, Hearing and Sight, all crowned by My sole desire.

Touch

Taste

Smell

Hearing

Sight

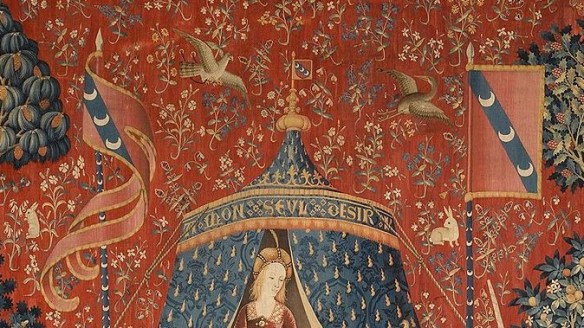

My sole desire

Now, the soul represents, at the individual level, an intermediary domain between the physical and spiritual ones. The soul is the individual reflection of the Principle at the source of all things, the Unity that governs the world. It consequently depicts a unifying principle of the various aspects of the being in general and his five senses in particular. A principle that is impalpable, without taste or odour, inaudible and invisible and not accessible by the sensitive way. In fact, only the immediate and direct way of intuition, beyond the simple sensation of feeling something, can give access to the principle knowledge. All the ambiguity of the meaning of the sixth tapestry results from the withheld approach: the strictly sensitive way of the physical being or the supra-sensitive way of the soul proper to the truly human being.

When manifested, the Principle successively actualizes the spiritual, psychical (including the individual soul) and physical aspects. Being a matter for the soul domain, the sense integration principle precedes the appearance of the five physical senses. Conversely, when the ordinary being follows the reversed way, he integrates the various aspects of his person, starting with the most physical, the five senses, which are resorbed into their unifying principle. Note that this double movement of descent and ascent, metaphysical and cosmological, can be found in all the traditional forms, including medieval.

- The coat of arms common to the six tapestries

The abundant presence of heraldry in the whole set of tapestries naturally evokes the chivalrous world, the courtly love and the willingness to assert one’s belonging to a noble line. Nevertheless, beyond the social importance, the repetition of the coat of arms on all six tapestries also has a symbolic meaning that illuminates the whole set.

The coat of arms is displayed in different forms: a shield, small shield or targe, standard, banner and cape with the coat of arms. The coat of arms represents three crescents argent (silver) on a bend azure (blue) on gules (red).

It shows a waxing Moon (![]() ) with the exception of the cape with the coat of arms worn by the lion in sense of taste (see the picture on the left) where the Moon is waning (

) with the exception of the cape with the coat of arms worn by the lion in sense of taste (see the picture on the left) where the Moon is waning (![]() ). The same waning Moon can equally be found at the back of the standard in sense of smell. Although the waxing Moon is more visible in accordance with a rising vision towards light, the waning Moon is nevertheless present at the back of the standard and banner. It follows that the coat of arms and the beings carrying them are related to the Moon phases.

). The same waning Moon can equally be found at the back of the standard in sense of smell. Although the waxing Moon is more visible in accordance with a rising vision towards light, the waning Moon is nevertheless present at the back of the standard and banner. It follows that the coat of arms and the beings carrying them are related to the Moon phases.

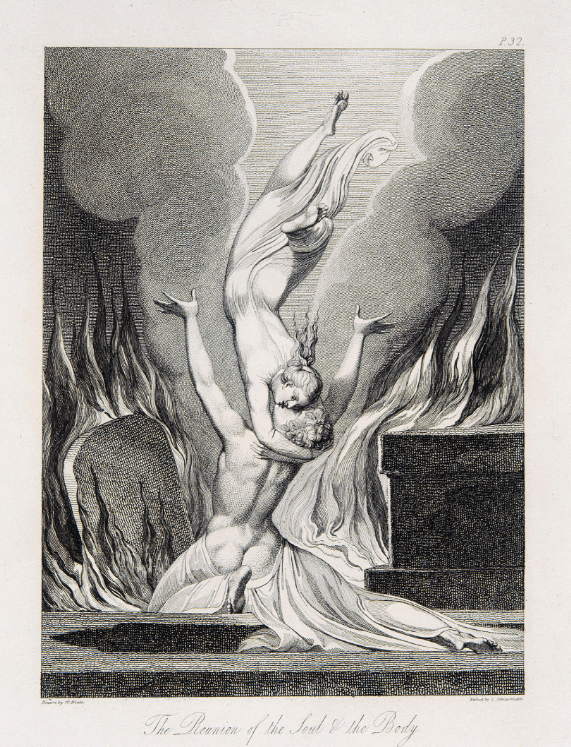

Just as the Moon waxes, wanes and disappears before reappearing, the being is born and dies before his re-birth. To the obscure and luminous periods of the Moon correspond the death to certain being’s states and the re-birth in other states of higher order. These state changes principally cover three types of birth:

- Physical giving rise to the ordinary being;

- Psychic (and individual soul) at the origin of the proper human being;

- Spiritual at the source of the supra-human being.

These three births correspond to the three Moon crescents. The first two are related to the ordinary and human nature of the individual and come within the lunar sphere. The third one, of supra-human nature, surpasses the individual order and gives access to the cosmic, indeed supra-cosmic order; the being leaves the lunar sphere to enter the solar sphere. In fact, the true light, the spiritual light can only emanate from the Sun for the Moon does nothing but reflect the solar light. To paraphrase a known saying, if Moon is silver, Sun is golden.

It follows that:

- The lunar light is a reflected, cool light, without heat, associated with reflection, individual reason and characterized by blue colour;

- The solar Light is a true, warm, radiating light that gives access to the supra-individual knowledge emanating from the heart and linked to red colour.

As it is necessary, the solar sphere (red) includes the lunar sphere (blue) for the lunar sphere is subordinated to the solar sphere.

The five first tapestries refer principally to the senses, attributes of the ordinary being, and come within lunar sphere alone. Regarding the last piece, it shows the way towards the solar sphere as we will see afterward. Note that the standard and banner poles appear in each tapestry and carry a horizontal crescent (![]() ) in a cup form.

) in a cup form.

In the medieval tradition, the cup is destined to receive a unifying element that contains all the others in a undifferentiated state, at the principle state. In a descending movement, the integrated principle is manifested notably under the appearance of the five senses; in an ascending movement, the five senses are resorbed into their principle state, i.e. unified.

- Mythical, exotic and familiar animals

The lion and the unicorn

The association of the lion, emblematic animal, with the unicorn, mythical animal, is frequent in the heraldic and medieval symbolic. The lion is generally sitting or standing on his hind legs with forelegs outstretched, the mouth open and a tongue sticking out. As for the unicorn (from the Latin “unicornus”), it is mostly represented as a bearded horse carrying a spiral horn on its forehead.

The reddish brown mane encircling the lion’s head symbolizes the terrestrial reflection of the celestial body, the Sun. As a producer of light and heat as the heart within the human body, the Sun is the life symbol in all its fullness, i.e. not only physical, but also psychic and spiritual. The lion is the image of the perfect mastered energy, of the sovereign force and whole power symbolizing at once royalty and Wisdom in the animal world. He does not need to show his claws to show his force.

The white unicorn is on the contrary associated with Moon. As the lunar light is only the reflection of the solar one, the unicorn depicts the feminine, passive principle counterpart of the masculine, active principle represented by the lion.

Of course, the Moon only shines through the Sun, but the Sun can only manifest his active aspect through its relation with the passive Moon. Just as the valiant knight only shines in the eyes of the noble Lady, the masculine principle is only manifested through the feminine principle. Only the manifestation of the oppositions masculine/feminine, active/passive, light/obscurity etc. allows the human being to overcome them and rejoin the world of Unity, the Principle at the source of all things. The double ascending and descending movement between the worlds of Unity and duality is represented by the spiral horn of the animal or rather by her both horns wound around each other as a braid. These two movements operate alongside a vertical axis that we rediscover in the standard or banner pole, the trunk of the trees or the pole carrying the circular pavilion.

The respective positions of the lion and unicorn on each side of the Lady underline the duality of the terrestrial world. The lion or the Sun is associated with full light or South and the unicorn or the Moon with obscurity or North. It follows that the Lady is facing East, the sunrise, the being’s elevation from the terrestrial horizon to the celestial zenith.

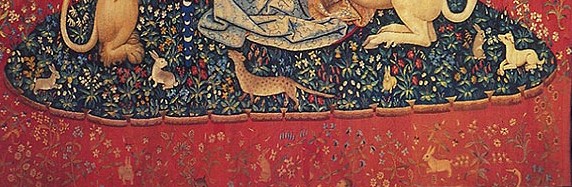

The other quadrupeds

The animals play an important role in heraldry and medieval world. The species covering the background dotted with flowers are familiar, wild or exotic: lamb, goat, hare, monkey, lion cub, young unicorn, panther, cheetah, dog, fox and wolf?

The lamb (in Taste) represents the active, luminous, solar principle that sacrifices his unitary origin in order to be manifested in all beings and in all worlds. Although, it is always essentially One and contains all beings and all worlds at a principle state, it externally appears as multiple. This is why, there are two lambs in the world: an inalterable one, standing in the immutable; the other sacrificed, fragmented and divided among all beings. The first is located in the Heart of the World, the second in the heart of men.

As the lion and the unicorn, the hare (in Sight) appears in all tapestries. As a nocturnal animal, it is associated with the Moon, the symbolism of which is ambivalent. Its waxing phase corresponds to the ascent towards light, knowledge; his waning phase depicts the descent towards obscurity, ignorance.This ambivalence is underlined by the background colour of the animal, divided in almost equal proportions between blue and red. Overcoming this dilemma means getting out of the lunar sphere (blue) to reach the solar sphere (red). In other words, it is a matter of dying to the states of the ordinary (synonymous of ignorance) and even human being to be re-born in the states of the spiritual being (fully conscious). The symbolism of the wolf, fox and other nocturnal animals comes under the same ambivalent character.

As the lion and the unicorn, the hare (in Sight) appears in all tapestries. As a nocturnal animal, it is associated with the Moon, the symbolism of which is ambivalent. Its waxing phase corresponds to the ascent towards light, knowledge; his waning phase depicts the descent towards obscurity, ignorance.This ambivalence is underlined by the background colour of the animal, divided in almost equal proportions between blue and red. Overcoming this dilemma means getting out of the lunar sphere (blue) to reach the solar sphere (red). In other words, it is a matter of dying to the states of the ordinary (synonymous of ignorance) and even human being to be re-born in the states of the spiritual being (fully conscious). The symbolism of the wolf, fox and other nocturnal animals comes under the same ambivalent character.

If the wolf decimates the animals bred by man, the dog (in Sight) is the flock guardian which protects from danger. It is undeniably the earliest domesticated animal and the faithful companion of man in his most noble activities, hunting notably. Besides, most of the animals represented in the Lady with the unicorn have a more or less direct connection with hunting. Now, this activity (associated with nobility at that time) takes on two symbolic aspects. On the one hand, the animal death symbolizes the destruction of the wild nature of the being, of his inner devils, of his obscure side. On the other hand, the pursuit and game tracking looks like a spiritual quest, a search for light in the depths of the forest.

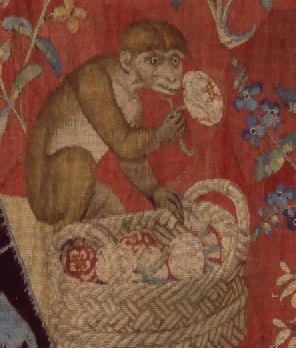

In contrast to the eastern tradition, the Christian and medieval tradition perceives the monkey (in Taste) in a negative way. It appears as the manifestation of the basic instincts of man, lust and of malice notably. Endowed despite all with a certain consciousness of the phenomenal world, it is recognized for its imitation faculties. The tapestries of Touch, Taste and Smell make such good use of this tendency that we could sometimes wonder if it is not rather man who monkeys about.

The birds

The birds usually play the role of messenger between Heaven and Earth. Various species (magpie, heron, hawk, partridge, pheasant, parrot and duck?) are displayed on all tapestries except one, Sight. The fact is surprising for an animal with a unequalled visual acuity. Nevertheless, the omission is not as astonishing as it appears. In fact, some traditions have gone as far as comparing the “birds in Heaven” to the “superior being’s states” i.e. to the states belonging to the world beyond, invisible in the eyes of simple mortals.

The birds usually play the role of messenger between Heaven and Earth. Various species (magpie, heron, hawk, partridge, pheasant, parrot and duck?) are displayed on all tapestries except one, Sight. The fact is surprising for an animal with a unequalled visual acuity. Nevertheless, the omission is not as astonishing as it appears. In fact, some traditions have gone as far as comparing the “birds in Heaven” to the “superior being’s states” i.e. to the states belonging to the world beyond, invisible in the eyes of simple mortals.

The preceding comparison is even more valid for hawk, the most represented bird in all pieces. As other birds, it is woven on a red background, the warm colour of the sunrise. It often symbolizes (with the eagle) the masculine and luminous principle, Sun, counterpart of the feminine and dark principle, Moon, associated with hare.

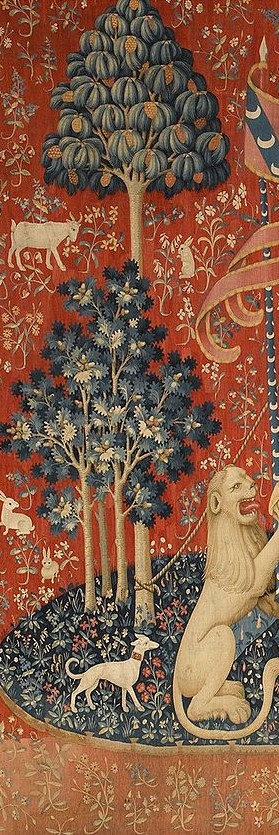

- Trees and flowers

Sessile oak, orange-tree, pine and holly

The six tapestries are decorated with two or four trees bearing fruit (sessile oak, orange-tree, pine and holly). The fruit contains seeds destined to be disseminated. The seed represents the germ, the grain source of a multitude of other trees. It symbolizes the primeval Unity, the Principle of the manifestation of all the beings and all the things. The inalterable character of Unity is notably underlined by the evergreen foliage (orange-tree, pine and holly) or the extreme longevity (sessile oak) of these trees

.

Tasting the fruit of the tree leads the being either to rediscover his spiritual original nature or to find his human or ordinary condition according to the tree nature:

Tasting the fruit of the tree leads the being either to rediscover his spiritual original nature or to find his human or ordinary condition according to the tree nature:

- The Fruit of the “Middle tree” erected at the “World Centre” or the “Tree of Life” located in the middle of the terrestrial Paradise confers to the being who tastes it the access to eternal life, to immortality proper to the spiritual world;

- The fruit of the “Tree of the knowledge of Good and Evil”, also situated in the garden of Eden, sends the one who tastes it back to his condition of ordinary being and to the duality of the temporal world.

Wild and cultivated flowers

The flower setting evokes the hanging patterns in medieval civil residences. Woven with the greatest care, this flower carpet constitutes a seedling of around forty species representative of the flora at that time. It is divided into:

- Wild flowers from fields and woods (columbine, aster, digital, wallflower, hyacinth, daffodil, marguerite, lily of the valley, daisy, periwinkle, Veronica, violet etc.);

- Cultivated flowers (jasmine, carnation).

Beyond its specific meaning, the flower symbolizes the feminine, passive principle of manifestation. It represents the receptacle, the cup destined to receive the masculine, active influence alongside the vertical axis notably depicted by the pole of the banner or standard. In this respect, it is similar to the horizontal crescent woven on the same pole.

Moreover, the blooming flower also portrays the development of the manifestation in all its diversity, a diversity represented by the flower variety and the number of petals.

This double meaning, as receptacle and development, is particularly true for the emblematic flower of the Middle Ages, the rose, appearing in the fence of Taste. The influence of Heaven is often symbolized by the “celestial dew” dropping from the Tree of Life and manifested into the variety of flowers, colours and perfumes.

It is particularly interesting to observe that this development is more obvious for wild flowers, symbols of the surrounding nature, than cultivated flowers, product of the medieval culture. The latter are in fact less numerous and carry five petals only depicting the five senses. The petals are placed around the chalice, heart of the flower symbolizing the “sixth sense”.

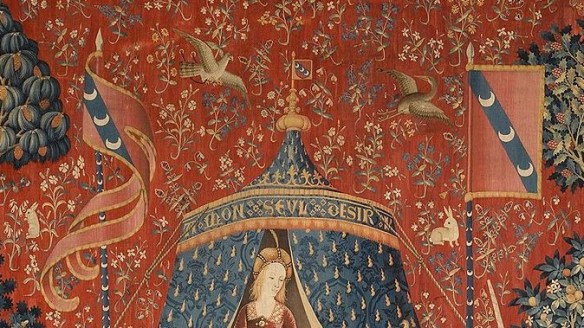

- “My sole desire”

The motto

Written at the top of the pavilion, the motto “My sole desire” is inserted between the two letters A and probably I or Y.

Would this motto be used as a link between two initials ? It seems to be really the case. At first, the three words of the motto are separated by two groups of five points so as to form a whole. Next, the motto is separated by a point from the first letter and two points from the second. The union of these two initials belonging to two beings is not my dearest wish, but my supreme, my ultimate, my unique, my only, my sole desire. Who can speak like that except the consignee(s) of the series of the six tapestries. Is it the couple itself or a close parent ?

This hymn to love would perfectly fit with the exacerbation of the five senses underlined by the presence of animals and plants in the series. And “My sole desire” could crown the whole set. Then, it would be easy to go on and on about the event continuation.

Nevertheless, the union of two beings that deeply love each other also symbolizes the union of the masculine and feminine natures within the couple. A union that tries to restore the unified, primeval or Edenic state preceding the fall. A fall that corresponds to the manifestation of the variety of beings and senses. The passage from the unified to the duality world, since the original state, is a necessary step to experience the senses and to become aware of the lost reality. If we give credit to Aristophanes in Plato’s mouth, love would be nothing but an attempt to rediscover the lost unity through the frantic quest of the soul mate. See The double meaning of the Androgyne.

Is the Lady this soul mate ? Is she ready to rejoin the one she loves in the pavilion ? Or else, is she in quest of this lost unity ? Will she rediscover the primeval state where the being no longer sees a world filled with antagonisms, but complementarities which are melting into Unity. Indeed, duality does not belong to the manifested world, but to our perception of that world. As long as we stay divided inside ourselves, we will not be able to accept the world as it is and ourselves as we are in reality, that means unified. The moment however we overcome our sensitive perceptions, go back against the original flow, attain the integrating principle governing our senses and become aware of the Unity ruling the world, all fears, cravings and illusions attached to our dualistic perception of things and beings are flying away. We are ready to leave the world of senses to rediscover the unified state of senses and being. We are ready to go back home, to leave the outer world to re-discover our inner world symbolized by the pavilion.

The pavilion

The pavilion immediately strikes the observer by the emptiness filling it. Emptiness reflects the non-manifestation of beings and things, the potentialized source, the Unity at the origin of everything in this world.

Even the central pole carrying the pavilion canvas is invisible. The pole represents the link between the big top of the pavilion, symbol of the celestial vault, and the ground covered with flowers and portraying the terrestrial world. Descended, the pole symbolizes the terrestrial manifestation of all beings and all things contained in the celestial Unity; ascended, it depicts the being ascension from his ordinary or terrestrial condition to the spiritual or celestial states.

It follows that:

- The way out of the pavilion corresponds to the way of the manifestation of beings and discovery of senses symbolized by the Lady carrying the necklace to her neck;

- The way into the pavilion expresses the return path from the outer experience of the senses towards the inner experience of the being described by the Lady getting rid of her jewels.

Representative of the World Axis, the pole rises to the zenith, the peak of the sun. It symbolizes the solar beam carrying light and irradiating the whole pavilion inside. The pavilion opening portrays the passage between the darkness of the midnight blue of the outer world and the light of the golden yellow of the inner world, between the lunar and the solar world and vice versa.

The Lady is still outside the pavilion. She may be ready to leave the world of senses, but only so she can reach the level of their integration. In contrast to the senses that only come within the bodily and outer domain, their integrated state borders on a relatively inner domain. It follows that even after having entered inside the pavilion, the lady will still be in the lunar sphere depicted by the blue ground. The elevation towards superior and spiritual states, alongside the Axis symbolized by the invisible pole, requests to go beyond the sole domain of the individual soul to reach the domain of the Soul of the World.

Expounding on concepts and principles of theophany, interconnectedness, interdependence, equilibrium and harmony, NTRC argues that roots of our various socioenvironmental crises lie primarily in a (human) crisis of consciousness. In

Expounding on concepts and principles of theophany, interconnectedness, interdependence, equilibrium and harmony, NTRC argues that roots of our various socioenvironmental crises lie primarily in a (human) crisis of consciousness. In

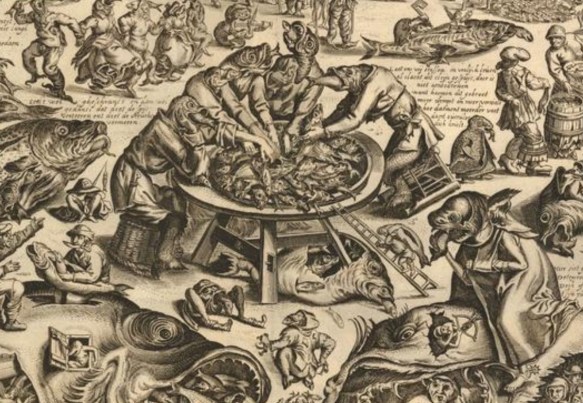

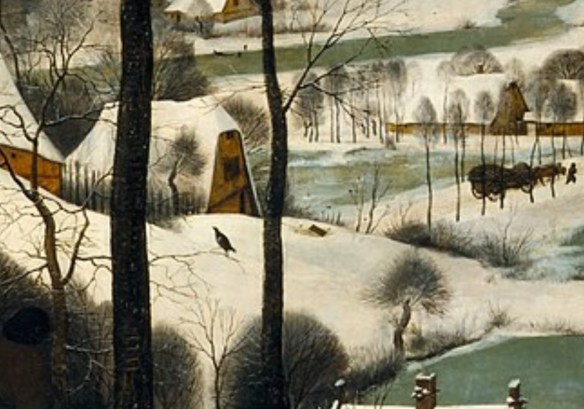

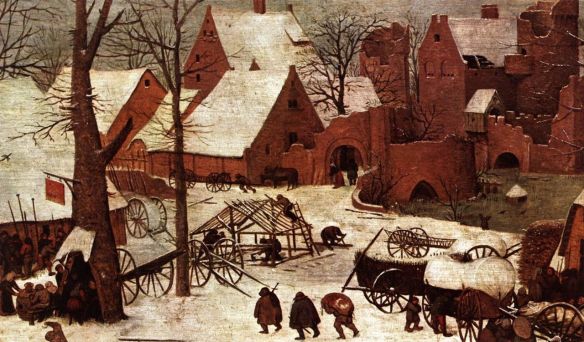

Bruegel includes different aspects of hunting in the image by depicting the group of hunters and dogs in the foreground, the inn that they pass on the left whose sign references St. Hubert, the patron saint of hunters, and a bird-trap in the left middleground.

Bruegel includes different aspects of hunting in the image by depicting the group of hunters and dogs in the foreground, the inn that they pass on the left whose sign references St. Hubert, the patron saint of hunters, and a bird-trap in the left middleground.

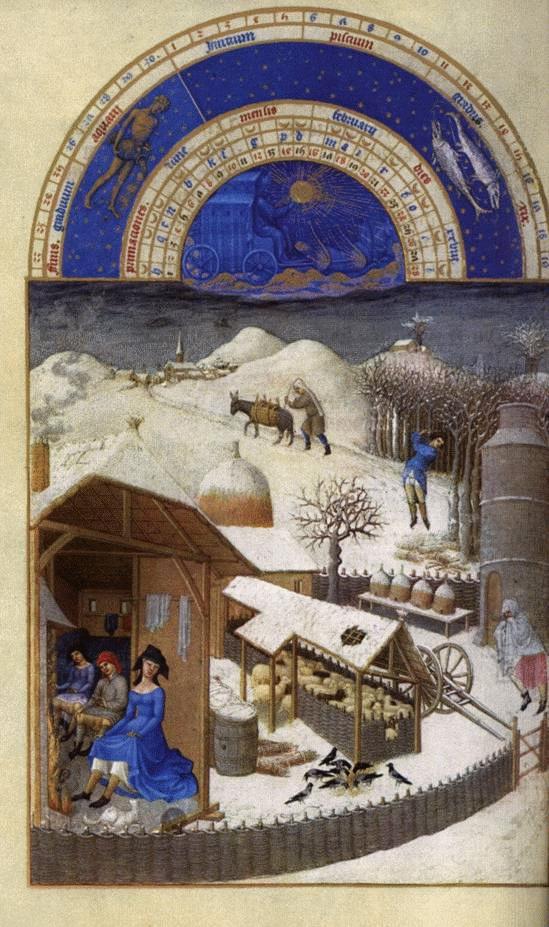

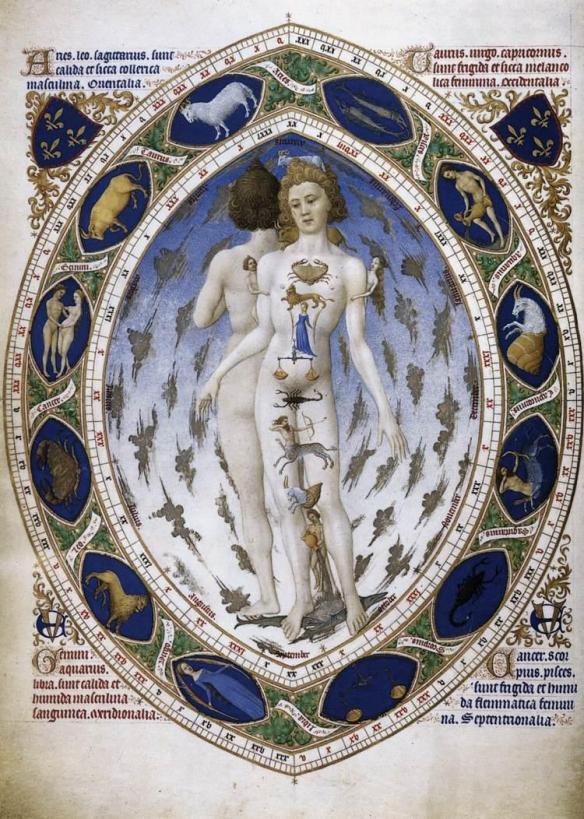

The labors are further contextualized by the inclusion of details pertinent to the patron or owner of a particular book of hours. In the case of the Tres Riches Heures of Jean, the Duke of Berry, the activities in the calendar illustrations take place not only beneath the zodiac signs and a star map, but also in the shadow of the duke’s palaces, depicted as accurate portraits in the background of many of the illuminations. In this way, the spiritual meaning of seasonal labor within a divine and cosmic cycle is focused for the book’s reader through the association with recognizable places. Similarly, in Hunters in the Snow, the labors and activities presented are subordinate to the broad landscape that suggests the region of Antwerp. Though the celestial and zodiac imagery are no longer present in the Months, Bruegel retains the idea of attaching familiar places to the activities depicted. Jongelinck’s world, like the duke’s in the Tres Riches Heures, looms over and around the seasons that Bruegel depicts.

The labors are further contextualized by the inclusion of details pertinent to the patron or owner of a particular book of hours. In the case of the Tres Riches Heures of Jean, the Duke of Berry, the activities in the calendar illustrations take place not only beneath the zodiac signs and a star map, but also in the shadow of the duke’s palaces, depicted as accurate portraits in the background of many of the illuminations. In this way, the spiritual meaning of seasonal labor within a divine and cosmic cycle is focused for the book’s reader through the association with recognizable places. Similarly, in Hunters in the Snow, the labors and activities presented are subordinate to the broad landscape that suggests the region of Antwerp. Though the celestial and zodiac imagery are no longer present in the Months, Bruegel retains the idea of attaching familiar places to the activities depicted. Jongelinck’s world, like the duke’s in the Tres Riches Heures, looms over and around the seasons that Bruegel depicts.

Falkenburg connects this sign and the reference to St. Hubert to the fact that it appears that the only catch the hunters return with is a single fox and, thus, any appeal the hunters may have made to the patron saint was not terribly effective. The author suggests that this is Bruegel’s way of showing that the meager catch is a result of the hunters not having St. Hubert properly in their hearts and that the figures of the hunters, looking down at their feet as they pass by the inn, function as negative examples for the viewer. They go about their labors without regard to the sign at the inn or that which it represents; they are spiritually blind to their patron saint and, by extension, oblivious to the revelation of Christ indicated in the sign’s portrayal of St. Hubert’s vision of the cross.xix The viewer of the image, if focused on exploring the painted terrain while ignoring the spiritual signs (and the inn’s actual sign), is implicated alongside the distracted hunters and their consequent meager spoils. Consequently, the viewer’s spiritual mode of perception reads these motifs as reminders to acknowledge the role of divine providence in the labors of the seasons. Perhaps, as some commentators have proposed, Bruegel shows himself here a “honest humorist” by suggesting that their scant catch results from not having St.Hubert “inden hert”: in their heart.

Falkenburg connects this sign and the reference to St. Hubert to the fact that it appears that the only catch the hunters return with is a single fox and, thus, any appeal the hunters may have made to the patron saint was not terribly effective. The author suggests that this is Bruegel’s way of showing that the meager catch is a result of the hunters not having St. Hubert properly in their hearts and that the figures of the hunters, looking down at their feet as they pass by the inn, function as negative examples for the viewer. They go about their labors without regard to the sign at the inn or that which it represents; they are spiritually blind to their patron saint and, by extension, oblivious to the revelation of Christ indicated in the sign’s portrayal of St. Hubert’s vision of the cross.xix The viewer of the image, if focused on exploring the painted terrain while ignoring the spiritual signs (and the inn’s actual sign), is implicated alongside the distracted hunters and their consequent meager spoils. Consequently, the viewer’s spiritual mode of perception reads these motifs as reminders to acknowledge the role of divine providence in the labors of the seasons. Perhaps, as some commentators have proposed, Bruegel shows himself here a “honest humorist” by suggesting that their scant catch results from not having St.Hubert “inden hert”: in their heart.

Samuel Parsons Scott’s three-volume history of the Moors in Spain and their influence on the culture of Western Europe was a landmark publication when it first came out in 1904. The first two volumes provide a detailed chronological history while the third volume presents aspects of the culture of al-Andalus, revealing the achievements of the Moorish empire and its impact upon Western scholarship and progress. Topics covered include the Moorish modes of conquest, government and administration; agriculture, trade and commerce; the influence of Moorish learning in science, literature and the arts; and reflections on Muslim social life and practices.Read Here:

Samuel Parsons Scott’s three-volume history of the Moors in Spain and their influence on the culture of Western Europe was a landmark publication when it first came out in 1904. The first two volumes provide a detailed chronological history while the third volume presents aspects of the culture of al-Andalus, revealing the achievements of the Moorish empire and its impact upon Western scholarship and progress. Topics covered include the Moorish modes of conquest, government and administration; agriculture, trade and commerce; the influence of Moorish learning in science, literature and the arts; and reflections on Muslim social life and practices.Read Here: Spain owes its special historical position in Europe very largely to his intensive encounter with the Orient. In the summer of 710, a small force under the command of a Berber named Taî f ibn Mâ lik landed to the west of Gibraltar. The Islamic armies that followed in its wake succeeded in conquering large areas of Spain within a short span of years. The conquerors gave the country the name of “”al-andalus.”” Thus began a period of cultural permeation that was to last for almost 800 years. In spite of intolerance and animosity, there developed between Muslims, Christians, and Jews a shared cultural environment that proved the basis for great achievements. Moorish-Andalusian art and architecture combine elements of various traditions into a new, autonomous style. Among the outstanding architectural witnesses to this achievement are the Great Mosque in Cordova and the Alhambra in Granada, recognized and admired as part of the world’s heitage right up to the present day. They are described in detail in this book. The main centres of Hispano-Islamic art and architecture, the cities of Cordova, Seville and Granada, are discussed within the chronological framework of developments, both political and cultural, from 710 to 1492.

Spain owes its special historical position in Europe very largely to his intensive encounter with the Orient. In the summer of 710, a small force under the command of a Berber named Taî f ibn Mâ lik landed to the west of Gibraltar. The Islamic armies that followed in its wake succeeded in conquering large areas of Spain within a short span of years. The conquerors gave the country the name of “”al-andalus.”” Thus began a period of cultural permeation that was to last for almost 800 years. In spite of intolerance and animosity, there developed between Muslims, Christians, and Jews a shared cultural environment that proved the basis for great achievements. Moorish-Andalusian art and architecture combine elements of various traditions into a new, autonomous style. Among the outstanding architectural witnesses to this achievement are the Great Mosque in Cordova and the Alhambra in Granada, recognized and admired as part of the world’s heitage right up to the present day. They are described in detail in this book. The main centres of Hispano-Islamic art and architecture, the cities of Cordova, Seville and Granada, are discussed within the chronological framework of developments, both political and cultural, from 710 to 1492.

This comprehensive collection of writings by the epoch-shaping Swiss psychoanalyst was edited by Joseph Campbell, himself the most famous of Jung’s American followers. It comprises Jung’s pioneering studies of the structure of the psyche – including the works that introduced such notions as the collective unconscious, the Shadow, Anima and Animus – as well as inquries into the psychology of spirituality and creativity, and Jung’s influential “On Synchronicity,” a paper whose implications extend from the I Ching to quantum physics. Campbell’s introduction completes this compact volume, placing Jung’s astonishingly wide-ranging oeuvre within the context of his life and times.

This comprehensive collection of writings by the epoch-shaping Swiss psychoanalyst was edited by Joseph Campbell, himself the most famous of Jung’s American followers. It comprises Jung’s pioneering studies of the structure of the psyche – including the works that introduced such notions as the collective unconscious, the Shadow, Anima and Animus – as well as inquries into the psychology of spirituality and creativity, and Jung’s influential “On Synchronicity,” a paper whose implications extend from the I Ching to quantum physics. Campbell’s introduction completes this compact volume, placing Jung’s astonishingly wide-ranging oeuvre within the context of his life and times.  “Before I discovered alchemy – writes Jung – I had a series of dreams which dealt with the same theme. Beside my house stood another, that is to say, another wing of annex, which was strange to me. Each tie I would wonder in my dream why I did not know this house, although it had apparently always been there”. This strange part of the house revealed its meaning finally: “The unknown wing of the house was a part of my personality, an aspect of myself…”

“Before I discovered alchemy – writes Jung – I had a series of dreams which dealt with the same theme. Beside my house stood another, that is to say, another wing of annex, which was strange to me. Each tie I would wonder in my dream why I did not know this house, although it had apparently always been there”. This strange part of the house revealed its meaning finally: “The unknown wing of the house was a part of my personality, an aspect of myself…”