In Praise of Folly, Erasmus

“The supreme madness is to see life as it is and not as it should be,

things are only what we want to believe they are ...”

Jacques Brel

Sloth – Acedia makes man powerless and dries out the nerves until man is good for nothing.”

Acedia (/əˈsiːdiə/; also accidie or accedie /ˈæksɪdi/, from Latin acēdia, and this from Greek ἀκηδία, “negligence”, ἀ- “lack of” -κηδία “care”) has been variously defined as a state of listlessness or torpor, of not caring or not being concerned with one’s position or condition in the world. In ancient Greece akidía literally meant an inert state without pain or care.

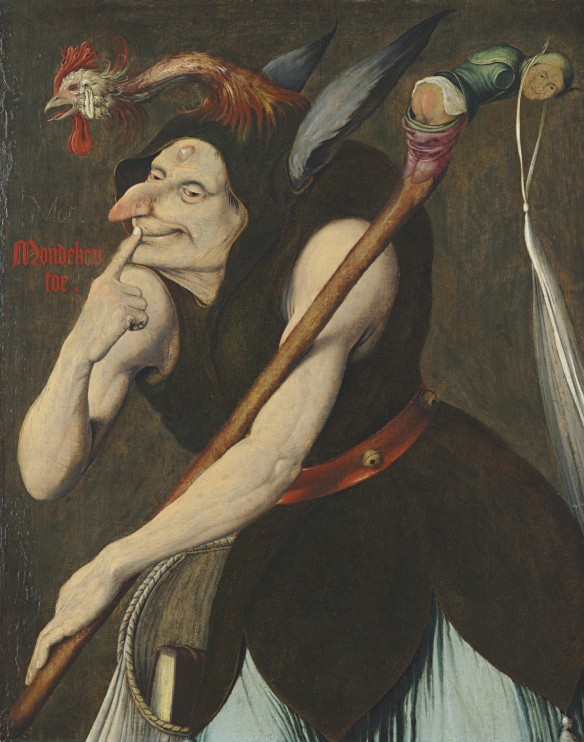

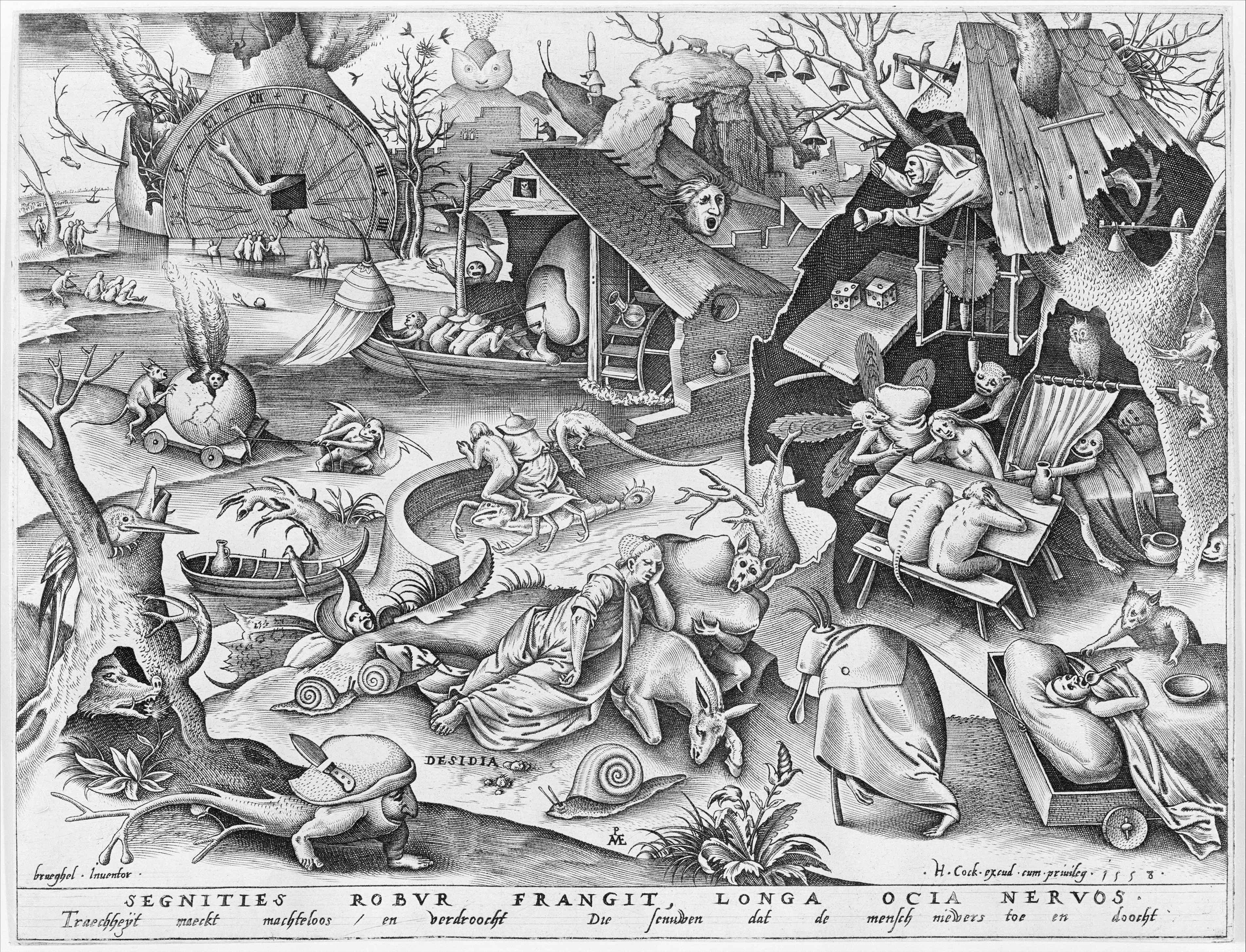

SLOTH (Laziness, Indolente, Desidia, Accidia, Pigritia, La Paresse, Trágheit,

The original drawing, in the Albertina, Vienna, is dated 1557.

Many a modern must find this not only the most passive and negative but in many ways the most haunting and shattering of Bruegel’s seven Sins.

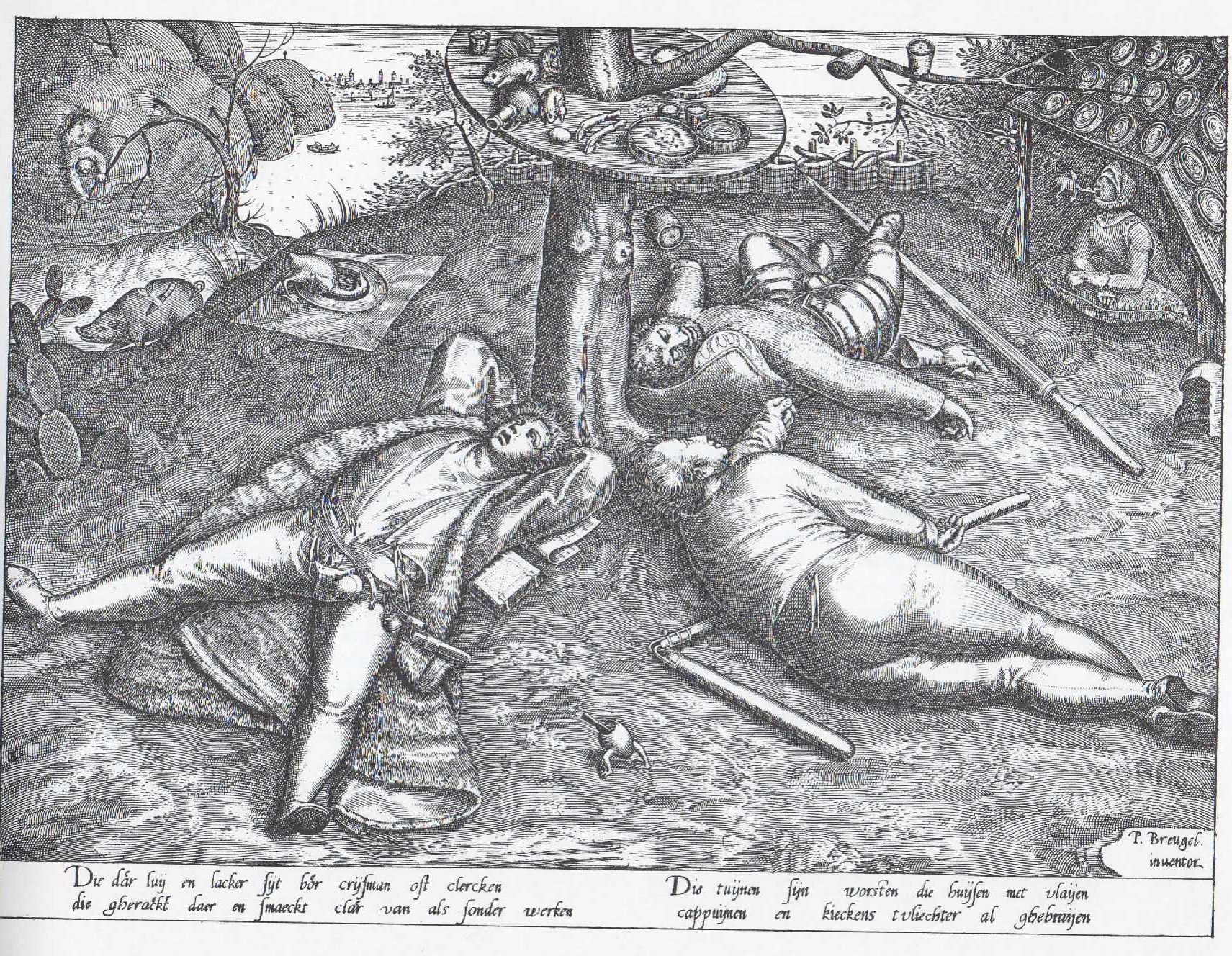

It symbolizes the evils of the vice which was treated with more irony and folksy fantasy in “The Land of Cockaigne,” reproduced as Plate 32. In that print, Plenty has destroyed ambition, energy, activity.

The arrangement of the clerk, peasant, and soldier underneath the tree suggests the men as the spokes of a wheel, where the tree is the hub. The roasted fowl lies in the place where a fourth spoke could be.

Ross Frank has argued that the painting is a political satire directed at the participants in the first stages of the Dutch Revolt (1568–1648), where the roasted fowl represents the humiliation and failure of the nobleman (who would otherwise form the fourth spoke of the wheel) in his leadership of the Netherlands, and the overall scene depicts the complacency of the Netherlandish people, too content with their abundance to take the risks that would bring about significant religious and political change.[3]

The painting has also been cited as illustrating the Freudian oral stage of psychosexual development,[4] showing a paradise of oral pleasure. It is used to demonstrate how human beings achieve oral pleasure and stimulation from eating and simply having things in the mouth.

see here more info: The land of Cocagne

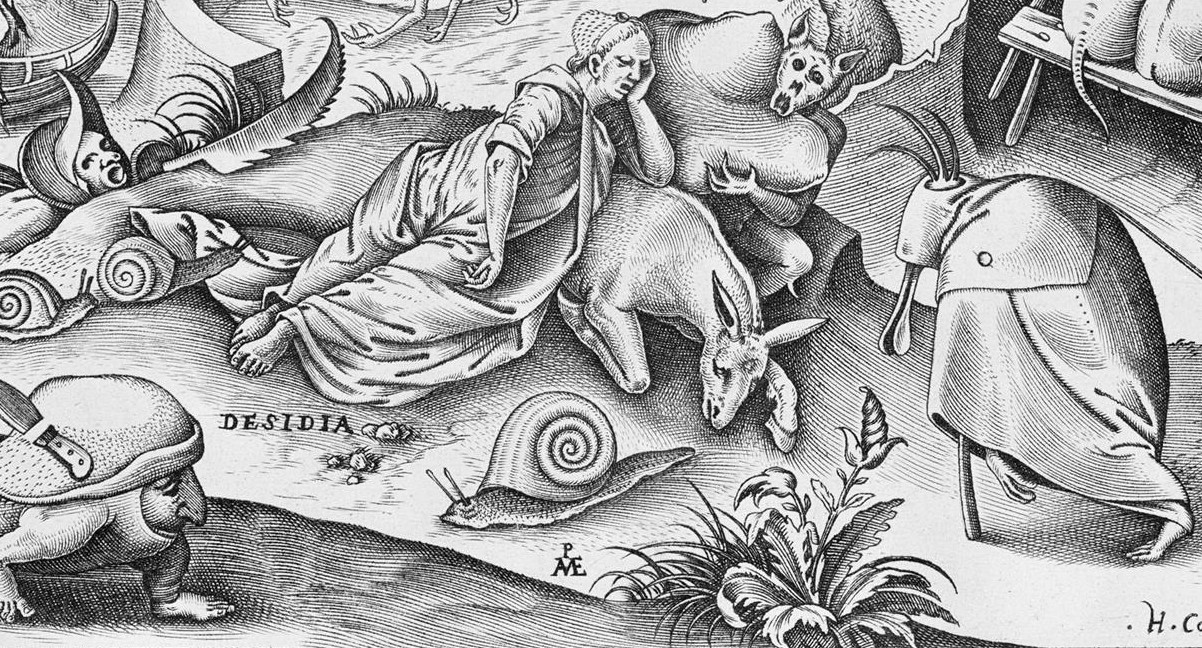

Here, Sloth herself, older and uglier than the other allegories, sleeps open-mouthed in a landscape of delay, decay, and ultimate impotence

She reposes on her beastly counterpart, a sleeping ass. A monster behind her adjusts her pillow. Around her crawl huge snails. Even the hill of Sloth is soft as shown by a winged demon sawing into it at left. One art historian sees the saw as a suggestion of Dame Sloth’s snoring as she sleeps. Another regards the sawman as a symbol for malicious gossip, his mouth ever open as he cuts away the ground from under others. ( To try to let the other come in problems).

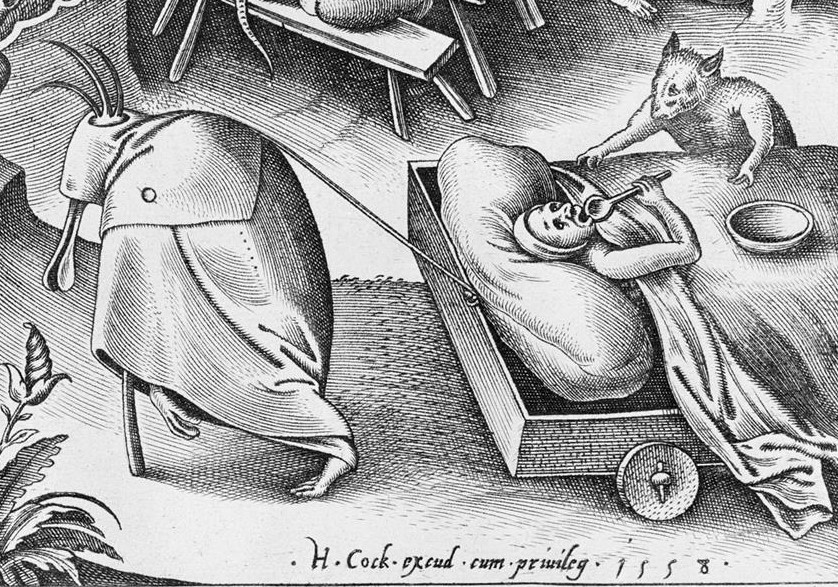

From the right, a stork-beaked monster in monk’s garb drags a sinner too indolent to leave his bed; he eats as he lies. The counterpart of this monk, Tolnay finds in Bosch’s ” Temptation of St. Anthony” painting (Lisbon). At the lower left, on a nearer hillock, trawls an all-head-and-feet monster, dragging a tail half fish, half branch. A hollow tree, farther left, contains a great pig’s head and provides a perch for a demon bird.

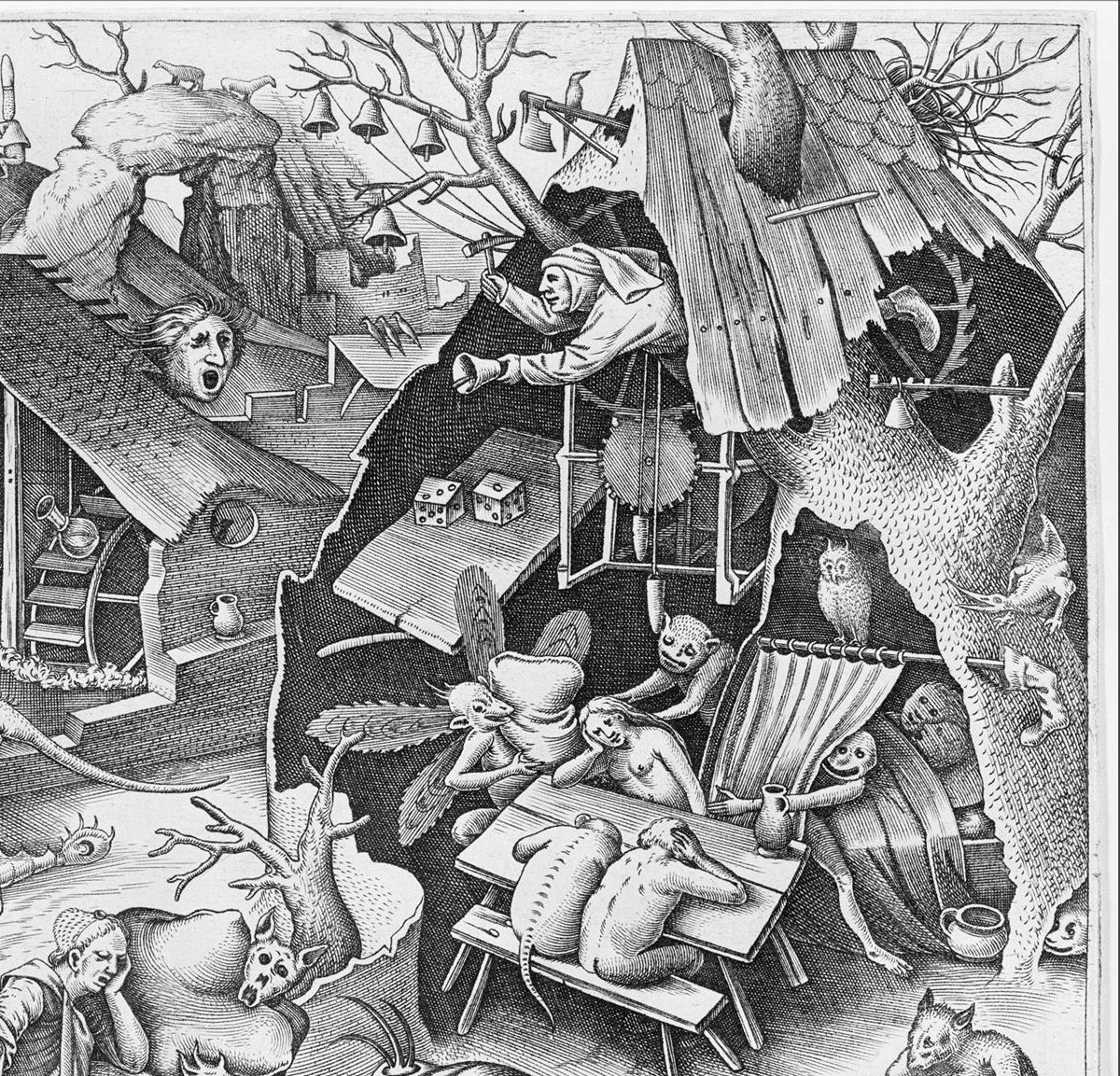

The hollow-tree symbol is extended enormously to the right of Dame Sloth. In this shell-like structure mingling building and tree, naked sinners and monsters sleep around a table. A couple lie together in bed behind a curtain. The demon leers around it as he seeks to draw the sleeping girl inside. Sloth or excess leisure encourages lechery. An owl, again, looks down cryptically.

Dice on the table to the left of the owl refer perhaps to gambling by lazy time-wasters. A man, caught in a great clockwork above, strikes a bell with a hammer. Tolnay reads this as a kind of pun, for in the Flemish lui ( Luid)signified both the verb “to ring” (as a bell), and the adjective “lazy.”

The idea of clock and time a-wasting appears again at the upper left. Like some effect in a Jean Cocteau motion picture, a human arm points to 11 o’clock. The lazy leave things till the eleventh hour.

And catastrophe lies behind—a blaze is burning up the broken structure, filled with dead branches.

A little to the right, just below the top margin, a mountain top with human face spouts smoke. A little farther to the right an enormous slug raises its feelers into the sky as it trawls through a stone arch. On its neck rides an almost unreadable strange distortion: a monster with a shaft (candle ?) instead of a head.

Below, just above center, a squatting giant, built into a mill, enacts a proverb common to many a culture: “He’s too lazy to shit.” The faceless midgets in the boat behind him are inducing a bowel movement with poles and pressure. Another owl looks through a small square window in the roof above this operation.

On the bank, somewhat to the left, two demons drag into the water of sin a woman almost bidden inside a seething hollow egg, which looks also like a beet or turnip.

References to many other Flemish proverbs have been shown or suspected. Basic to the complicated spectacle as a whole is the thought in the Flemish rhyme below the print. It is roughly rendered in English thus : Translation of Latin caption: Sloth breaks strength, long idleness ruin the sinews

The various examples of lazy or slothful behavior, in evidence in the surrounding landscape, colorfully demonstrate the message of the inscription below: “Sloth makes man powerless and dries out the nerves until man is good for nothing.”

In short, sloth, far from resting, recuperating and rejuvenating,waste a man away, renders him impotent and good for nothing. He becomes like a slug, a slave of the stupefied tyrant machine, DAME Desidia or Acedia , ἀκηδία, “negligence”, ἀ- “lack of” -κηδία “care”) has been variously defined as a state of listlessness or torpor, of not caring or not being concerned with one’s position or condition in the world.

Mentally, acedia has a number of distinctive components of which the most important is affectlessness, a lack of any feeling about self or other, a mind-state that gives rise to boredom, rancor, apathy, and a passive inert or sluggish mentation. Physically, acedia is fundamentally associated with a cessation of motion and an indifference to work; it finds expression in laziness, idleness, and indolence.

Emotionally and cognitively, the evil of acedia finds expression in a lack of any feeling for the world, for the people in it, or for the self. Acedia takes form as an alienation of the sentient self first from the world and then from itself. Although the most profound versions of this condition are found in a withdrawal from all forms of participation in or care for others or oneself.

Sloth not only subverts the livelihood of the body, taking no care for its day-to-day provisions, but also slows down the mind, halting its attention to matters of great importance. Sloth hinders the man in his righteous undertakings and thus becomes a terrible source of human’s undoing

In his Purgatorio Dante portrayed the penance for acedia as running continuously at top speed. Dante describes acedia as the “failure to love God with all one’s heart, all one’s mind and all one’s soul”; to him it was the “middle sin”, the only one characterised by an absence or insufficiency of love, virtue and uprightness.

The antidote Industria meaning Craftmanship , Diligence ,Persistence, effortfulness, ethics, Virtues and sincere uprightness.

- The Tower of Babel by Breughel

The Tower of Babel was the subject of three paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The first, a miniature painted on ivory, was painted while Bruegel was in Rome and is now lost.[1][2] The two surviving paintings, often distinguished by the prefix “Great” and “Little”, are in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna and the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam respectively. Both are oil paintings on wood panels.

The (Great) Tower of Babel

The (Little) Tower of Babel

The Rotterdam painting is about half the size of the Vienna one. In broad terms they have exactly the same composition, but at a detailed level everything is different, whether in the architecture of the tower or in the sky and the landscape around the tower. The Vienna version has a group in the foreground, with the main figure presumably Nimrod, who was believed to have ordered the construction of the tower,[although the Bible does not actually say this. In Vienna the tower rises at the edge of a large city, but the Rotterdam tower is in open countryside.

The Rotterdam painting is about half the size of the Vienna one. In broad terms they have exactly the same composition, but at a detailed level everything is different, whether in the architecture of the tower or in the sky and the landscape around the tower. The Vienna version has a group in the foreground, with the main figure presumably Nimrod, who was believed to have ordered the construction of the tower,[although the Bible does not actually say this. In Vienna the tower rises at the edge of a large city, but the Rotterdam tower is in open countryside.

The paintings depict the construction of the Tower of Babel, which, according to the Book of Genesis in the Bible, was built by a unified, monolingual humanity as a mark of their achievement and to prevent them from scattering: “Then they said, ‘Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.‘” (Genesis 11:4).

The Viennese “Big” Tower, is almost twice as large as the Rotterdam “Little” Tower and is characterized by a more traditional treatment of the subject. Based on Genesis 11: 1-9, in which the Lord confounds the people who began to build “a tower whose top may reach unto Heaven”, it includes – as the other version does not – the scene of King Nimrod and his retinue appearing before the genuflecting crowd of workmen. This event is not mentioned in the Bible but was suggested in Flavius Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews. It was important to Bruegel as underlining the sin of the King’s pride and overbearing which the picture is supposed to highlight. See more here

The Viennese “Big” Tower, is almost twice as large as the Rotterdam “Little” Tower and is characterized by a more traditional treatment of the subject. Based on Genesis 11: 1-9, in which the Lord confounds the people who began to build “a tower whose top may reach unto Heaven”, it includes – as the other version does not – the scene of King Nimrod and his retinue appearing before the genuflecting crowd of workmen. This event is not mentioned in the Bible but was suggested in Flavius Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews. It was important to Bruegel as underlining the sin of the King’s pride and overbearing which the picture is supposed to highlight. See more here

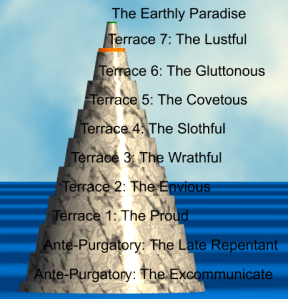

Dante purgatory:

Seven terraces of Purgatory

Seven terraces of Purgatory

After passing through the gate of Purgatory proper, Virgil guides the pilgrim Dante through the mountain’s seven terraces. These correspond to the seven deadly sins or “seven roots of sinfulness”] Pride, Envy, Wrath, Sloth, Avarice (and Prodigality), Gluttony, and Lust. The classification of sin here is more psychological than that of the Inferno, being based on motives, rather than actions.[22] It is also drawn primarily from Christian theology, rather than from classical sources The core of the classification is based on love: the first three terraces of Purgatory relate to perverted love directed towards actual harm of others, the fourth terrace relates to deficient love (i.e. sloth or acedia), and the last three terraces relate to excessive or disordered love of good things.[21] Each terrace purges a particular sin in an appropriate manner. Those in Purgatory can leave their circle voluntarily, but may only do so when they have corrected the flaw within themselves that led to committing that sin.

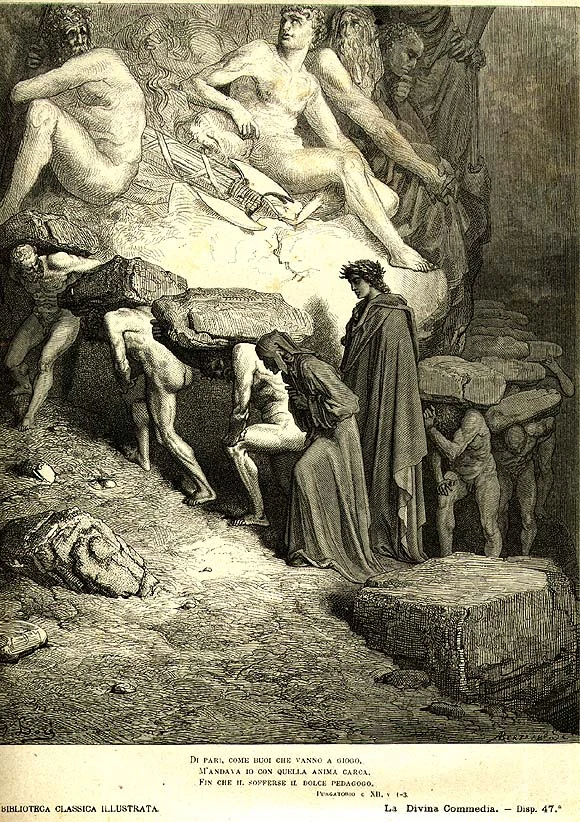

- Essentially Dante devises in Purgatorio 10 a way of describing moving images in words: he is describing moving pictures/movies/film, though the medium does not yet exist. The same miraculous medium is used for the 13 examples of punished pride that are described in Purgatorio 12. While the carved examples of the virtue of humility are on the wall of the terrace, the examples of the vice of pride are on its pavement, like pavement tombs the pilgrim has seen on earth, but more lifelike due to the “artificio” (artifice [Purg. 12.23]) of their maker.

A spectacular acrostic displays the 13 examples of pride almost “visually”; see the attached chart for a list of all the examples. Note the interweaving of biblical and classical examples and how the exempla of pride reflect the three types of pride dramatized by the encounters with the three souls of Purgatorio 11. The examples are arranged in the following pattern: four sets of terzine begin with the word “Vedea”; four sets of terzine begin with the word “O”; four sets of terzine begin with the word ‘Mostrava”. Thus twelve examples of pride spell out VOM or UOM, “man” in Italian, signifying that pride is man’s besetting sin.

The thirteenth terzina offers the final example, which sums up all the others by referring to a city rather than to a person and by replicating in one terzina all three of the letters that spell the acrostic:

Vedeva Troia in cenere e in caverne; o Ilión, come te basso e vile mostrava il segno che lì si discerne! (Purg. 12.61-63)

I saw Troy turned to caverns and to ashes; O Ilium, your effigy in stone— it showed you there so squalid, so cast down!

The characters featured as examples of pride would repay lengthy discussion. Here we find Nembrot, he who built the tower of Babel and who spoke gibberish to Dante and Virgilio in Inferno 31:

Vedea Nembròt a piè del gran lavoro quasi smarrito, e riguardar le genti che ’n Sennaàr con lui superbi fuoro. (Purg. 12.34-36)

I saw bewildered Nimrod at the foot of his great labor; watching him were those of Shinar who had shared his arrogance.

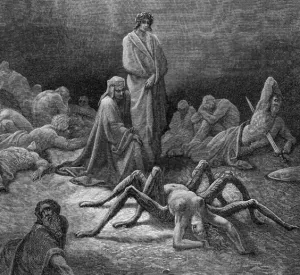

Most important to my reading of the terrace of pride is the mythological figure of Arachne, marked by the Ulyssean adjective “folle”:

O folle Aragne, sì vedea io te già mezza ragna, trista in su li stracci de l’opera che mal per te si fé. (Purg. 12.43-45)

O mad Arachne, I saw you already half spider, wretched on the ragged remnants of work that you had wrought to your own hurt!

Arachne was famous for her weavings that were so lifelike that they seemed alive. The passage describing her work in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, discussed in Chapter 6 of The Undivine Comedy, nourished Dante in his conceptualizing of representational arrogance as the cornerstone of his terrace of pride (see the Introduction to Purgatorio 11). Again, as in Purgatorio 10’s depiction of the “visibile parlare” of the sculpted virtues, in Purgatorio 12 the point is hammered home that this art is not just “life-like”, it is “life” itself:

Morti li morti e i vivi parean vivi: non vide mei di me chi vide il vero, quant’io calcai, fin che chinato givi. (Purg. 12.67-69)

The dead seemed dead and the alive, alive: I saw, head bent, treading those effigies, as well as those who’d seen those scenes directly.

At the end of the canto we encounter another of the ritual components of the purgatorial experience, repeated on each terrace: Dante meets the angel and a “P” is removed from his brow, signifying his successful participation in the purgation of one “peccatum” or vice/sin. He climbs toward the next terrace, and as he climbs he hears a shortened form of the first Beatitude: “Beati pauperes spiritu” (Matthew 5:3). The eight Beatitudes are from Christ’s Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:3-10) and will be featured on the purgatorial terraces. In full, this Beatitude, featured on the terrace of pride to celebrate the soul’s new acquisition of a pride-less “poverty of spirit”, is: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

- Educating Desire: Conversion and Ascent in Dante’s Purgatorio

by Paul A. Camacho

Paul A. Camacho in his paper asks our attention “Why the Purgatorio? As first-time readers discover with surprise in the closing cantos of Dante’s Inferno, Hell is defined primarily by stasis. Where there is motion in Hell, it is only the tormented self-circling of a will that cannot love anything beyond itself. Hell is the place that Dante scholar Peter Hawkins has memorably described as “repetition-compulsion, an endless replay of the sinner’s ‘song of myself.’” It is certainly true, as Dante saw, that conversion requires an underworld itinerary: we can no overcome the drive to get what we mistakenly think will bring us happiness through intellectual understanding or sheerwill-power alone. But to journey throug hHell as Dante would have us do,one must experience one’s sin and failure without getting trapped in it; and this means one must face all the darkness in oneself without becoming entombed by fear, despair, or gawking fascination. This is a heavy task for anyone, let alone for the average undergraduate. By contrast, Purgatory is, in Hawkins’ words, “dynamic, dedicated to change and transformation.It concerns the rebirth of a self free a tlast to be interested in other souls and other things .” It is fruitful to dwell in Purgatorio with students because it is in Purgatory that we now reside. I mean this: in Hell there is no time, there is only infinite stasis; in Paradise there is no time, but rather the dynamic over-abundance of eternity; only in Purgatory is there time,because only here is there the possibility of change and growth. If we read the Commedia to learn how to love better here and now, in this world, it is the Purgatorio that will provide the blueprint.”

In Cantos 17 and 18 of the Purgatorio, Dante’s Virgil lays out a theory of sin, freedom, and moral motivation based on a philosophical anthropology of loving-desire. As the commentary tradition has long recognized, because Dante placed Virgil’s discourse on love at the heart of the Commedia, the poet invites his readers to use love as a hermeneutic key to the text as a whole. When we contextualize Virgil’s discourse within the broader intention of the poem—to move its readers from disordered love to an ordered love of ultimate things—then we find in these central cantos not just a key to the structure and movement of the poem ,but also a key to understanding Dante’s pedagogical aim. With his Commedia, Dante invites us to perform the interior transformation which the poem dramatizes in verse and symbol. He does so by awakening in his readers not only a desire for the beauty of his poetic creation, but also a desire for the beauty of the love described therein. In this way, the poem presents a pedagogy of love, in which the reader participates in the very experience of desire and delight enacted in the text. In this article, I offer an analysis of Virgil’s discourse on love in the Purgatorio, arguing for an explicit and necessary connection between loving-desire and true education. I demonstrate that what informs Dante’s pedagogy of love is the notion of love as ascent, a notion we find articulated especially in the Christian Platonism of Augustine. Finally, I conclude by offering a number of figures, passages, and themes from across the Commedia that provide fruitful material for teachers engaged in the task of educating desire. Read more here

A lifelong pilgrimage: The Mirror of Jheronimus bosch

- This panel symbolizing the “all seeing eye” or “eye of salvation” structurally, it is like a circle of “Seven deadly sins

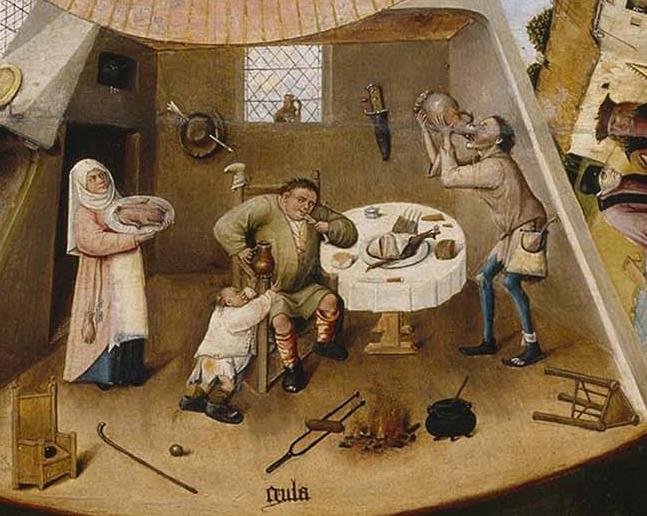

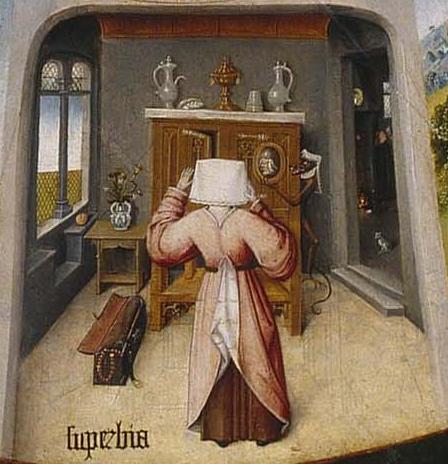

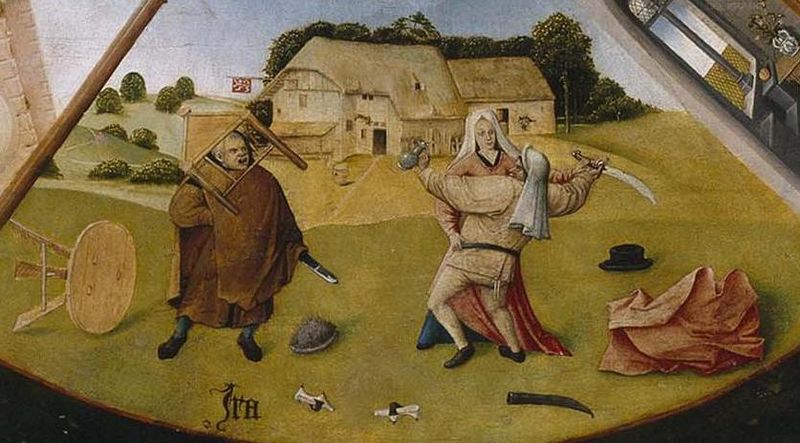

Four small circles, detailing the four last things — Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell — surround a larger circle in which the seven deadly sins are depicted: wrath at the bottom, then (proceeding clockwise) envy, greed, gluttony, sloth, extravagance (later replaced with lust), and pride, using scenes from life rather than allegorical representations of the sins.[4]

At the centre of the large circle, which is said to represent the eye of God, is a “pupil” in which Christ can be seen emerging from his tomb. Below this image is the Latin inscription Cave cave d[omi]n[u]s videt (“Beware, Beware, The Lord Sees”).

Above and below the central image are inscription in Latin of Deuteronomy 32:28–29, containing the lines “For they are a nation void of counsel, neither is there any understanding in them”, above, and “O that they were wise, that they understood this, that they would consider their latter end!” below.

Each panel in the outer circle depicts a different sin. Clockwise from top (Latin names in brackets):

- Gluttony (gula): A drunkard swigs from a bottle while a fat man eats greedily, not heeding the plea of his equally obese young son.

- Sloth (acedia): A lazy man dozes in front of the fireplace while Faith appears to him in a dream, in the guise of a nun, to remind him to say his prayers.

- Lust (luxuria): Two couples enjoy a picnic in a pink tent, with two clowns (right) to entertain them.

- Pride (superbia): With her back to the viewer, a woman looks at her reflection in a mirror held up by a demon.

- Wrath (ira): A woman attempts to break up a fight between two drunken peasants.

- Envy (invidia): A couple standing in their doorway cast envious looks at a rich man with a hawk on his wrist and a servant to carry his heavy load for him, while their daughter flirts with a man standing outside her window, with her eye on the well-filled purse at his waist. The dogs illustrate the Flemish saying, “Two dogs and only one bone, no agreement”.

- Greed (avaricia): A crooked judge pretends to listen sympathetically to the case presented by one party to a lawsuit, while slyly accepting a bribe from the other party.

The four small circles also have details. In Death of the Sinner, death is shown at the doorstep along with an angel and a demon while the priest says the sinner’s last rites, In Glory, the saved are entering Heaven, with Jesus and the saints, at the gate of Heaven an Angel prevents a demon from ensnaring a woman. Saint Peter is shown as the gatekeeper. In Judgment, Christ is shown in glory while angels awake the dead, while in the Hell demons torment sinners according to their sins.

Seven Deadly Sins

- Pride (Superbia)

- Wrath (Ira)

- Envy (Invidia)

- Greed (Avaricia)

Four Last Things

- “Hell” and the punishment of the seven deadly sins.

- “Glory” or Heaven

- THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS AND THE FOUR LAST THINGS THROUGH THE SEVEN DAY PRAYERS OF THE DEVOTIO MODERNA

Christ’s gaze in Bosch’s painting draws the viewer’s attention. When a member of the Devotio Moderna looked at the painting during his daily prayers, he underwent serious

self-examination which was possible because “visual images” served as a still more effective vehicle for compassionate meditation.

Devils and the Angel’s Mirrors.

Without the gaze of Christ, the painting would not have as great an impact on its viewer in a time of meditation. When the viewer meditates upon the seven day prayers of the Devotio Moderna, he/she sees the image of Christ as the Man of Sorrows looking at him or her. Through this interaction with Christ, the viewer examines his own morals and keeps his faith in God. The viewer’s world is not the physical environment where he lives but the one that is reflected in the Eye of God. As the viewer prays upon the seven day prayers, he will be guided to the Kingdom of Heaven where he will be greeted by the angels and face Christ without any shame or guilt upon the death of the redeemer. The righteous person will keep his faith in God as he sees the image of Christ in the Eye of God.

The eye creates an eternal exchange of the interaction between the viewer and Christ As the image reflects the ‘inner perception’ of the viewer, Bosch’s painting reflects the viewer’s own consciousness in choosing between right and wrong as he undergoes the daily meditations of the seven day prayers of the Devotio Moderna.

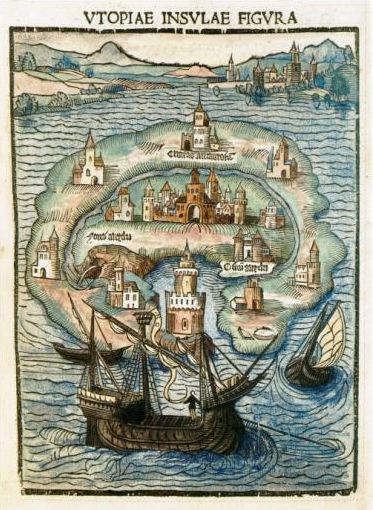

Utopia and the Devotio Moderna:

The Brabantine mysticism of Jan van Ruusbroec and the Priory of Groenendaal,

the Modern Devotion of Geert Grote and the spiritual and religious thought of

Erasmus and More through Utopia and other key works of Christian humanism.

Maarten Vermeir -University College London

Two Renaissance work serve me well as interpretation keys for Thomas More’s

book of Utopia.

My first interpretation key will always remain Desiderius Erasmus’ Praise of Folly

or Moriae Encomium.

As you all know, Erasmus wrote his Praise of Folly in the house of More and the

narrator of his Praise, Lady Stultitia or Moria, is ironically linked to the name of

Thomas More. Lady Moria orates a great amount of nonsense, but through

Erasmus’ fine irony at the same time a great deal of wise and rightful criticism

on aspects and figures of his contemporary society. At the end of her Praise,

Stultitia speaks also about a deeper mystical, Christian folly and considering

similar statements by Erasmus in other works like his Enchiridion Militis

Christiani, these statements of Lady Stultitia were seriously meant by Erasmus.

Also in Thomas More’s Utopia we can recognize a mixture of serious ideas

through the eyes of More and Erasmus (about the institution of the state and

church, international relations, the division between church and state,

spirituality, religion and tolerance, social care, culture/education? And

matrimonial policies) with also nonsensical ideas to their opinion (the economic

system, the travel restrictions inside the Utopian state). A search for their ideas

on these points through other works and their personal orientations makes the

recognition of such mixture unavoidable. In Utopia we can probably find more

serious concepts than nonsensical, and although this partition was reversed in

the earlier Praise of Folly, the family similarity on this point remains paramount

and crucial to a correct understanding.

The narrator of More’s Utopia, Raphael Hythlodaeus(in one of the two meanings

translated as ‘Merchant of Nonsense’, in the other as ‘Destroyer of Nonsense’)

is linked reciprocally to Erasmus through the figure of Saint Erasmus, as I learned

recently, the patron of all sailors. Also reciprocally, Thomas More started

probably writing the book of Utopia in one of the major residences of Erasmus

in the Low Countries: the Antwerp house of his friend Pieter Gillis.

My second preferred interpretation key for More’s Utopia consists in the 900

theses of Pico della Mirandola.

Thomas More translated ‘The Life of Pico della Mirandola’ and was undoubtedly

aware of della Mirandola’s philosophical program: in his famous 900 theses Pico

della Mirandola intended to combine into a higher synthesis the best elements

of classical traditions, especially from the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle, with

aspects of the Jewish-Christian traditions, especially mystical elements like he

found in the Jewish Kabbala. His great endeavor was to formulate a consistent

marriage between Jewish-Christian mysticism and the rich humanistic learning

by which he was surrounded in Renaissance Florence. His early death prevented

him regretfully from executing this great master plan. But the Christian

Humanists around Erasmus and Thomas More would become Pico’s true

inheritors and take Pico della Mirandola’s scheme as a blueprint for their

complete literary oeuvre and philosophical program. One of Utopia’s layers of

meaning is certainly a broad defense of the Christian humanistic ideals. The

serious parts of Utopia can be read as an honorary tribute to Pico della

Mirandola’s audacious plans, as a literary realization of Pico’s inspiring dreams.

These traces of della Mirandola’s program in Utopia will be subject of my later

research.

Both works, Erasmus’ Praise of Folly and della Mirandola’s 900 theses have thus also a deeper Mystical meaning and importance.Also Thomas More’s Utopia has.

As a religious community Utopia knows only a few strict and unbreakable rules for the religious life of its citizens. Next to these respected rules, there is complete liberty for personal spirituality and thus room for many different colorings, orientations and institutions of the Utopians’ personal spiritual life. In this way each Utopian is also destined and commissioned to set out on a personal spiritual journey, encouraged by the daily contact between the elder and the

children or youngsters, sitting daily side by side with every meal.

This is also the foundation of Utopia’s religious tolerance and freedom: the

undeniable points of belief (the eternal soul, divine presence and activity in the

world, the punishment of vices and the rewarding of virtues – and thus the

rewarded or punished free will of men) have to be respected by all Utopians, and

all personal, by definition different additions in respect of these rules, are

tolerated in the Utopian state. These undeniable points were instituted by

Utopus himself and public challenges outside the closed company of priests and

officials, are punished severely to safeguard the common interest and public

order of the state. So the gap between the institution of Utopian tolerance and

later political actions of Thomas More, is therefore less deep and less broad as

often depicted. In his discussion with Luther on the Free Will, Erasmus stated

also that Luther shouldn’t discuss his ideas with or spread amongst the ordinary

people but discuss with qualified persons.Read more here