The Brabantine mysticism of Jan van Ruusbroec and the Priory of Groenendaal,

the Modern Devotion of Geert Grote and the spiritual and religious thought of

Erasmus and More through Utopia and other key works of Christian humanism.

Maarten Vermeir -University College London

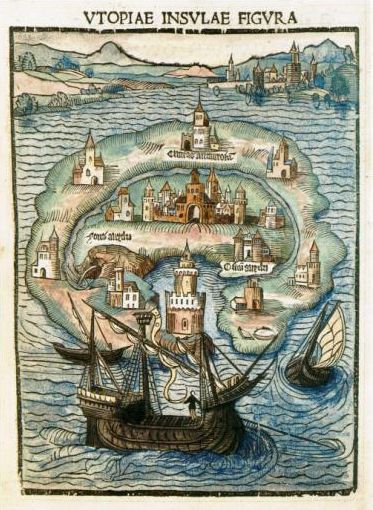

Two Renaissance work serve me well as interpretation keys for Thomas More’s

book of Utopia.

My first interpretation key will always remain Desiderius Erasmus’ Praise of Folly

or Moriae Encomium.

As you all know, Erasmus wrote his Praise of Folly in the house of More and the

narrator of his Praise, Lady Stultitia or Moria, is ironically linked to the name of

Thomas More. Lady Moria orates a great amount of nonsense, but through

Erasmus’ fine irony at the same time a great deal of wise and rightful criticism

on aspects and figures of his contemporary society. At the end of her Praise,

Stultitia speaks also about a deeper mystical, Christian folly and considering

similar statements by Erasmus in other works like his Enchiridion Militis

Christiani, these statements of Lady Stultitia were seriously meant by Erasmus.

Also in Thomas More’s Utopia we can recognize a mixture of serious ideas

through the eyes of More and Erasmus (about the institution of the state and

church, international relations, the division between church and state,

spirituality, religion and tolerance, social care, culture/education? And

matrimonial policies) with also nonsensical ideas to their opinion (the economic

system, the travel restrictions inside the Utopian state). A search for their ideas

on these points through other works and their personal orientations makes the

recognition of such mixture unavoidable. In Utopia we can probably find more

serious concepts than nonsensical, and although this partition was reversed in

the earlier Praise of Folly, the family similarity on this point remains paramount

and crucial to a correct understanding.

The narrator of More’s Utopia, Raphael Hythlodaeus(in one of the two meanings

translated as ‘Merchant of Nonsense’, in the other as ‘Destroyer of Nonsense’)

is linked reciprocally to Erasmus through the figure of Saint Erasmus, as I learned

recently, the patron of all sailors. Also reciprocally, Thomas More started

probably writing the book of Utopia in one of the major residences of Erasmus

in the Low Countries: the Antwerp house of his friend Pieter Gillis.

My second preferred interpretation key for More’s Utopia consists in the 900

theses of Pico della Mirandola.

Thomas More translated ‘The Life of Pico della Mirandola’ and was undoubtedly

aware of della Mirandola’s philosophical program: in his famous 900 theses Pico

della Mirandola intended to combine into a higher synthesis the best elements

of classical traditions, especially from the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle, with

aspects of the Jewish-Christian traditions, especially mystical elements like he

found in the Jewish Kabbala. His great endeavor was to formulate a consistent

marriage between Jewish-Christian mysticism and the rich humanistic learning

by which he was surrounded in Renaissance Florence. His early death prevented

him regretfully from executing this great master plan. But the Christian

Humanists around Erasmus and Thomas More would become Pico’s true

inheritors and take Pico della Mirandola’s scheme as a blueprint for their

complete literary oeuvre and philosophical program. One of Utopia’s layers of

meaning is certainly a broad defense of the Christian humanistic ideals. The

serious parts of Utopia can be read as an honorary tribute to Pico della

Mirandola’s audacious plans, as a literary realization of Pico’s inspiring dreams.

These traces of della Mirandola’s program in Utopia will be subject of my later

research.

Both works, Erasmus’ Praise of Folly and della Mirandola’s 900 theses have thus also a deeper Mystical meaning and importance.Also Thomas More’s Utopia has.

As a religious community Utopia knows only a few strict and unbreakable rules for the religious life of its citizens. Next to these respected rules, there is complete liberty for personal spirituality and thus room for many different colorings, orientations and institutions of the Utopians’ personal spiritual life. In this way each Utopian is also destined and commissioned to set out on a personal spiritual journey, encouraged by the daily contact between the elder and the

children or youngsters, sitting daily side by side with every meal.

This is also the foundation of Utopia’s religious tolerance and freedom: the

undeniable points of belief (the eternal soul, divine presence and activity in the

world, the punishment of vices and the rewarding of virtues – and thus the

rewarded or punished free will of men) have to be respected by all Utopians, and

all personal, by definition different additions in respect of these rules, are

tolerated in the Utopian state. These undeniable points were instituted by

Utopus himself and public challenges outside the closed company of priests and

officials, are punished severely to safeguard the common interest and public

order of the state. So the gap between the institution of Utopian tolerance and

later political actions of Thomas More, is therefore less deep and less broad as

often depicted. In his discussion with Luther on the Free Will, Erasmus stated

also that Luther shouldn’t discuss his ideas with or spread amongst the ordinary

people but discuss with qualified persons.

Seen the revolutionarily broad scale on which the Chrisitian humanists promoted

their cultural, political and spiritual/religious agenda for the entire Respublica

Christiana, the promotion of their religious and spiritual ideas is in se also

revolutionary in Utopia, as stated here already, even a key manifesto of the

Christian humanistic ideals and trough the force of fiction, a wide applicable

exemplum for all states and peoples inspired by Thomas More’s Magnum Opus.

This is why Sanford Kessler stated that ‘his reading of Utopia shows that modern

religious freedom has Catholic, Renaissance roots.’

The printing scale and literary-philosophical reach of this religious and spiritual

promotion was indeed unprecedented.

These ideas however were not original.

The roots of Utopia’s religious freedom and personal spirituality can be traced

back to the great Mystical tradition of the Low Countries and the neighboring

Rhineland.

One of the three books anyone should read according to Thomas More, was ‘The

imitation of Christ’ by Thomas a Kempis, a prominent representative of the

Modern Devotion. Also Jean-Claude Margolin found striking similarities between

‘The imitation of Christ’ and Erasmus’ Enchiridion Militis Christiani, stating at the

same time that a major cause of these similarities could be the shared

background and shared context of the Modern Devotion, in which also Erasmus

was raised and educated as a child and as a youngster – in my view decisively for

his later religious and spiritual views and writings. Although he has had indeed

also bad experiences with figures formally connected to the Modern Devotion,

this movement started by Geert Grote was really significant and inspiring for

Erasmus too. Geert Grote founded the first houses of the Brethren and Sisters of

the Common Life (in 1374 and 1383), echoed in Utopia in the two religious

schools and through the shared common property inside Geert Grote’s

households maybe even in the entire economic institution of the Utopian state.

To counter criticism on the Brehtren and Sisters of the Common Life, Geert Grote

requested on his deathbed – and his successor Florence Radewyns would execute

this – the foundation of the monastery of Windesheim with some Brethren taking

the form of an Augustinian order, heading later the congregation of

Windesheim. By doing so, they followed the example and living principles of the

Priory of Groenendaal, founded by Jan van Ruusbroec, two other canons, a good

cook and a layman some fourty years earlier (in 1343) in the Forêt de Soignes

outside the city of Brussels. Jan van Ruusbroec, the great master of Brabantine

mysticism or doctor admirabilis, constituted with his settlement in 1343 a new

religious community with a less strict structure and more room for personal

spiritual development in the Green tranquility of the forest around Groenendaal,

taking the form of an Augustinian canon’s monastery in 1349 to counter criticism

and avoid further suspicion. The reputation of Groenendaal priory and of

Ruusbroec’s teachings, through his oral explanations and beautiful writings in

Medieval Brabantine Dutch, would reach far inside the Low Countries and

outside. Geert Grote came to visit Jan van Ruusbroec even in Groenendaal as

many did (in 1378-1379). In 1413, the Windesheim congregation even absorbed

the monastery of Groenendaal, turning it into a priory. This specific tradition with

less stringent structures and more liberty for personal spirituality, would become

defining through the spreading force of its focus on education, its great success

in the Low Countries and beyond and its uniqueness inside the Catholic Church,

defining for the Brabantine and Netherlandish mystical tradition and its

pioneering role in Late Medieval Europe.

Different translations of Ruusbroec’s works in Latin and other languages were

even spread over Europe in different lines of subsequently copied manuscripts,

already from the second half of the 14th century. A Latin translation of

Ruusbroec’s main work ‘de geestelijke bruiloft’/ ‘the spiritual wedding’ about the

different phases and risks of the evolving process of a human seeking unity with

the Divine throughout his life, was printed for the first time in 1512 by Jacques

Lefèvre d’Etaples. Most intriguingly, Erasmus visited this friend in 1511 and had

with him ‘a number of intimate conversations’. At the end of the 15th century

already, Erasmus had visited the priory of Groenendaal, learned from the living

exemplum of Groenendaal’s institutions and organization and spent days there

studying in its library: with his zeal he surprised even the monks, taking books

with him at night to his dormitory. So it is certainly possible that around 1515,

both Erasmus and Thomas More knew the works of Ruusbroec very well from

first hand, not only through works of Devotio Moderna’s protagonists like

Thomas a Kempis, inspired by Geert Grote and Ruusbroec himself.

Also other key aspects of Utopian society can be linked to the Brabantine

Mysticism of Jan van Ruusbroec. As the political system of Utopia was inspired

by the Joyous Entries of Brabant from 1356, Jan van Ruusbroec received the

grounds for his firstly settled community in Groenendaal directly from Duke Jan

III, who would allow at the end of his life the composition of the first Joyous Entry

in 1356, arranging the succession of his daughter. Dux Utopus would institute

the religious freedom in Utopia immediately after his victory over the fighting

religious sects he found in Utopia upon his arrival. Ruusbroec would write also

his most influential book ‘de geestelijke bruiloft’ in the preceding decades. As

architect of the Tower and enlargement of the city hall of Brussels, one of the

four capitals of Brabant, was even chosen and appointed in the mid-15th century

a Jan van Ruisbroec, by name referring to the Mystical Master.

Also Pierre d’ Ailly and Jean Gerson, the fathers of conciliarism as found in the

institution of the Utopian church, were directly familiar with the Brabantine

mysticism of Ruusbroec: Jean Gerson had a keen interest in the teachings of the

Brabantine master, and even discussed eagerly about a detailed topic. Pierre

d’Ailly followed these engagements of his pupil from a first row seat, as the

bishop of Cambrai under whose ecclesiastical jurisdiction the priory of

Groenendaal fell, integrating into the congregation of Windesheim under his

watch (till 1411).

The Civic humanism – both political and religious – in Utopia was in many aspects

closely related to and inspired by this Netherlandish civic humanism, and this

connection will be treated in my further research exhaustively.

Certain elements strengthen these bonds between ‘More’s Utopia and the Low

Countries’, paraphrasing the title of my RSA conference paper for Moreana, in

New York 2014.

In Jean Desmarez’ prefatory poem for Utopia, the different gifts and talents of

different European countries are attributed to the state of Utopia: only one

country is missing in this overview, the Low Countries, showing a collision and

combination into a higher synthesis of the different cultural traditions strongly

present there. For Pico della Mirandola and his program, the Low Countries

would have constituted a true dreamland in this perspective, a cultural

laboratory Erasmus and Thomas More could encounter directly.

And as Marisa Bass stated recently, the group around Gerard Geldenhouwer was

excited about the discovery that ‘Roman writers such as Julius Caesar, Pliny the

Elder, and Tacitus had long ago described the Netherlands as a body of land

surrounded on all sides by water.’

And in Anemolius’ prefatory poem for Utopia we find the statement that ‘Utopia

is a rival of Plato’s republic, perhaps even a victor over it. The reason is that what

he delineated in words Utopia alone has exhibited in men and resources and

laws of surpassing excellence.’

I recently counted all the places considered as real cities in the Duchy of Brabant

and connected territories, this calculation resulted in the number of 54 cities,

the same number as the number of cities in Utopia.

Together with the political protection offered by chancellor Jean le Sauvage, this

is why I believe the first edition of Utopia was printed in Leuven, also one of the

four capitals of Brabant, why Utopia’s opening scenery is situated in the city of

Antwerp, also a capital of Brabant and the main Brabantine port, and why

Thomas More requested Erasmus to provide him also with politicians – from the

Low Countries where Erasmus was staying at the moment of this request – as

writers of the prefatory letters for Utopia. These places have their interpretative

meaning and significance. Indeed, Thomas More’s embassy to the Low Countries

was truly an ‘Utopian embassy’

- The Devotio Moderna

The movement which became known as the Devotio Moderna emerged towards the end of the fourteenth century against the background of great social and religious insecurity. War, epidemics and social unrest characterized everyday life. The Church was divided by theWestern Schism (1378–1417) between rival popes in Rome and Avignon. Various movements, of which the Devotio Moderna was one, reacted by seeking to reform the Church from within. See The Modern Devotion. Confrontation with Reformation and Humanism

Institutionally the movement began in Deventer in the Low Countries, in the valley of the IJssel River, through the efforts of Geert Grote (1340–1384) and his followers. As son of a Deventer merchant, Grote belonged to the relatively privileged civic patrician class. In 1355 he studied at the university in Paris, first the liberal arts, later also theology, law and medicine. According to his own report, a serious illness around 1374 became a turning point in his life: he gave up his prebends, returned to Deventer, and in his parental home founded the first common institution, the “Meester-Geertshuis,” for what became known as the Sisters of the Common Life.

The goal of the DevotioModerna has been succinctly summarized by R.Th.M. vanDijk: “The charisma which they shared was the so-called devotio moderna: by means of a dedicated inner life (devotio) and in a suitably contemporary manner (moderna) striving to emulate the example of the first Christians for the renewal of an ailing church (Reform).”

Over the next two hundred years, the movement spread throughout the northern and southern Low Countries, in German-speaking territories to Bordesholm in the north and Jasenitz (today’s Poland) in the east, into northern Switzerland and the north-east of France. In a sense the history of the DevotioModerna has two separate aspects which are not always distinct or distinguishable: its own—quite complex—institutional history, and the history of its reforming influence. There are hints that these different histories also resulted in some differences in the use of music—an example would be the prose translations for liturgical music in institutions which devoted themselves to the Latin liturgy, versus collections of vernacular religious songs from institutions in which Latin played a more minor role. This complex question is touched on by the essays which follow, but it remains a matter for more concentrated research.

The first institutions founded by the Devotio Moderna were houses in which Brothers or Sisters of the Common Life lived together, acting in most respects as monastics but retaining lay status as they did not take monastic vows.

Brother and Sister Houses continued to be founded throughout the fifteenth century, although there was a marked trend to stricter enclosure through the adoption of Augustinian or the rule of the ThirdOrder of St Francis, especially for Sister Houses.

Already early on, during Grote’s own life, thought was given to starting a monastic branch of the movement, which would provide some institutional safeguards as well as a measure of security against constant opposition by the mendicant orders.

Two years after Grote’s death in 1384 this plan was realized: as the Windesheim canon Johannes Busch reports, in 1386 Windesheim (near Zwolle) became the Devotio Moderna’s first cloister, inhabited by six canons regular living according to Augustinian rule. It was followed by others, and in 1395 the four cloisters Windesheim, Nieuwlicht, Eemstein and Marienborn joined to form the Chapter of Windesheim. The first Augustinian cloister for women, Diepenveen (close to Deventer), was founded at the beginning of the fifteenth century; it joined the Windesheim chapter in 1414.

Of the many Sister Houses which strove for cloistered status in the course of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, only a few were admitted to Windesheim. As a result others combined to form congregations such as the “Chapter of Sion” (also called the “Chapter of Holland”), and the “Chapter of Venlo.” These chapters maintained many of the ideals of the Devotio Moderna and are also to be counted among the women’s institutions of the movement.

The adoption of Franciscan lay rule resulted in a third institutional branch of the Devotio Moderna, the female tertiaries belonging to the Chapter of Utrecht. In this the Utrecht tertiaries were early adopters, for already in 1399 the first such Franciscan tertiary houses combined to form that Chapter. Like other houses which accepted the third rule of the Franciscans as their governing order, they maintained the movement’s religious ethos, for their visitatores (examining assessors) and confessors were primarily priors of Windesheim cloisters or Brothers of the Common Life.

The second aspect of the movement’s history is its influence on many existing convents belonging to other orders. In the second half of the fifteenth century, it was instrumental in an extensive effort to reform monasteries in northern Germany, especially Benedictine and Cistercian cloisters. Closely tied to the success of this so-called Bursfeld Reform movement was the introduction of the ideas and ideals of the Devotio Moderna.

In this Johannes Busch was a key figure; his years of tireless efforts and many long journeys for the cause are described in his two remarkably detailed reports.

Among the many cloisters subject to monastic reform in the spirit of the Devotio Moderna were six women’s institutions on the Lüneburg Heath, now commonly called the “Lüneburger Frauenklöster.” The introduction of reform led to a stricter adherence to the official liturgy, but also to increased study of religious texts about personal spirituality, among them writings of Grote and Thomas a Kempis. A number of these cloisters producedmanuscripts, and especiallyMedingen became known for both vernacular and Latin prayer books. As a result, we have fromMedingen a considerable number of sometimes beautifully executed manuscripts combining prayers and other meditative texts with liturgical music, songs, and images.

In France the Devotio Moderna was much less of a factor, though Johannes Mauburnus, canon in Agnietenberg (near Zwolle), was assigned the task of reforming five monasteries in the area of Paris. In this he had only limited success, for only the canons of the Abbey of Livry, where Mauburnus became abbot near the end of his life, showed inclination for the ideals of the movement.For us, Mauburnus’ chief legacy is an intriguing tract on methodical meditation containing directives about the role of music in devotion.

While the Devotio Moderna grew rapidly in the fifteenth century, this was also its most flourishing period. During the sixteenth century it was virtually wiped out by the success of the Reformation by Martin Luther and John Calvin. Only a few monastic communities survived this development. The last Windesheim canon died in the cloister of Sulta nearHildesheim (Germany) in 1865.

- Meditation Practice in the Devotio Moderna

The goal of the Devotio Moderna was to return to the way of life of the early Christians, in order to rediscover the true Christian faith. To achieve this, adherents lived in small communities within cities, earning their keep with various kinds of manual labour. At the same time, personal spiritual development was the most important aim of their lives. This development of one’s own soul, described in detail by several authors, was essential if one was to become a citizen of the heavenly Jerusalem after death and be united with Christ.

In this respect the Devotio Moderna was closely aligned with developments in late-medieval spirituality across Europe. The most important theological influences were, besides St Augustine, also Bonaventura und Jean Gerson.

An important method of spiritual development was meditation on central theological themes, particularly hell, heaven, death, and the Passion of Christ.

Such meditation was to be virtually ceaseless—every waking hour, including and perhaps especially those not structured by the usual offices of the day, was to be devoted to it. Communion with God through prayer was the ultimate goal of meditation; key tools were memoria and ruminatio, the latter intended to encourage constant reflection on devotional material consigned to memory, forming the most immediate layer of consciousness for constant and effortless recall.

The meditative process was intended to “inflame the affect” (affectio) in order to achieve the heartfelt understanding required for true communion with the divine through prayer.

Meditative material was supplied by official readings in Latin (lectio) but other sources as well. In order to assist their own meditation, many individuals compiled a personal rapiarium, pieces of paper or a small booklet gathering significant extracts for later repetition and reflection, a religious version of the “commonplace book” as it is known in the English tradition A few of these private rapiaria were sufficiently extensive that they formed the basis for considerable tracts later circulated as authored treatises. A well-known example is the rapiarium of Gerlach Peters, which after his death was reworked by Johannes Schutken into the treatise now known as Soliloquium.

For adherents of the Devotio Moderna, meditation was complemented by obligatory manual labour, held by St Augustine to be a centralmonastic activity.

Since it was impossible to only meditate, meditation ought to be combined with work. Such work should, in turn, be interrupted regularly by meditation and prayer. Standing in this Augustinian tradition, the Devotio Moderna accepted manual labour as constitutive element of its piety, as for example the theologian and Brother of the Common Life at Deventer, Gerard Zerbolt van Zutphen (1367–1398) shows in his De spiritualibus ascensionibus.Like St Augustine, Zerbolt considered it advisable that regular work be combined with prayer and meditation.

For Zerbolt, ideal work (especially for the male devout) consisted of writing religious books. This activity reduced the distance between manual labour and spiritual development because the writing itself was a de facto occupation with religious content; in addition, the result—religious books—contributed to the spiritual development of others, which counted positively for the contributor.

Nikolaus Staubach has characterized this key element of the movement as “pragmatic literacy” (pragmatische Schriftlichkeit): writing religious books was a spiritual act which profited not only the reader but also the writer through insight into matters of faith. This process, described by Thom Mertens as “reading with the pen,” also had an effect on the nature of the texts which have come down to us.

The majority of religious books were liturgical books needed for daily celebration of the sacrifice of God’s son and salvation of mankind. Brothers of the Common Life must have written hundreds of liturgical books for convents and churches in their neighbourhood. At Cologne, ’s- Hertogenbosch, Tilburg, Münster and Xanten dozens of liturgical manuscripts written by the Brothers have survived. Producing religious books was not limited to writingwith hands. Printing, notably of liturgical books, also advanced spiritual development. The newly founded community of Brothers at Marienthal was the first printer of liturgical books north of the Alps, especially reformed liturgical texts for the new German Bursfeld Congregation of Benedictines, and diocesan breviaries.

Another important and influential aspect of the movement’s spirituality was the translation of Latin texts into the vernacular in order to make them available for those who had not mastered this language sufficiently. The best known example is the Middle Dutch book of hours of Geert Grote which was transmitted all over Northern Europe. Vernacular translations of liturgical hymns and sequences in particular were intended to assist in understanding the Latin liturgy of the Mass and Office, which would otherwise have been emotionally inaccessible to many, especially women.

The organization and the extent of meditational schemes increased in complexity through time. In the early years there was little proscription: adherents meditated in the morning upon arising, and in the evening before going to bed. Extant from the second half of the fifteenth century are weekly schedules which spread a number of meditation programmes thematically over the course of seven days.A final text of this genre, arguably a culmination for the genre, was the Rosetum spiritualium exercitiorum et sacrarum meditationum by Mauburnus, first printed in 1494. This extensive treatise contains numerous meditative exercises whichwere to be performed in exactly prescribed sequences on particular days of the week and at particular times of each day. In the late Middle Ages, several monastic orders such as Carthusians, Cistercians, and Benedictines also used methodical meditation as a way to support personal spiritual development. This explains in part why ideas of theDevotio Moderna influenced so many houses of these orders: method and ideas were transmitted symbiotically.

Also look to the works of The Blessed John van Ruysbroeck (Dutch: Jan van Ruusbroec, pronounced [ˈjɑn vɑn ˈryzbruk]; 1293 or 1294 – 2 December 1381) was one of the Flemish mystics. Some of his main literary works include The Kingdom of the Divine Lovers, The Twelve Beguines, The Spiritual Espousals, A Mirror of Eternal Blessedness, The Little Book of Enlightenment, and The Sparkling Stone. Some of his letters also survive, as well as several short sayings (recorded by some of his disciples, such as Jan van Leeuwen). He wrote in the Dutch vernacular, the language of the common people of the Low Countries, rather than in Latin, the language of the Church liturgy and official texts, in order to reach a wider audience. Read here The Spiritual Espousals See also Translation of the “Third Life” into English and “The Contemplative Life”: To Be God with God.

The same experience happened also to the great mystic Al Hallaj see Martyrdom of al Hallaj and Unity of the Existence Wahdat al-wujud or Oneness of the Absolute Existent

While the general meditational practice just described has frequently been the object of research, especially from the perspective of church history and literary history, there are numerous indications that music, too, played an important role in this activity.

- Music and Meditation

In the context of meditation, not only texts but also music had an important function. In particular, music was intended to give rise in the personmeditating the proper and desired affect or emotion (affectio), the emotion that, based on the text or reading (lectio), should result from the meditatio in order to flow into effective prayer to God (oratio). Awareness that music affected the emotions was not new, stemming as it did from Antiquity. The idea entered into the treatises and the ideas of the Devotio Moderna through writings such as St Augustine’s De opera monachorum, and the Etymologiae of Isidorus of Sevilla.0

St Augustine’s view is reflected in specific treatises by authors of the Devotio Moderna, for example Zerbolt and Radewijns, and by many more general sources which report about music being involved in meditation.

The music manuscripts of the Devotio Moderna reveal connections with the practice of daily meditation in various ways, both in content and in codicological features. A considerable number of song texts make concrete references to meditation, daily schedules for spiritual exercises point to song during meditation, and some song collections were organized on the basis of meditation programs

The use of music had a shadow-side, however. Beneficial though the influence of music could be in generating the desired affect, it was a danger for those who lost sight of the text connected with the music. For inherent in singing was the possibility that a song’s music would be accorded greater prominence than the text carried by the music. Music and false affect were specifically connected by St Augustine in his Confessions:

Thus I fluctuate between peril of pleasure and approved wholesomeness; inclined the rather (though not as pronouncing an irrevocable opinion) to approve of the usage of singing in the church; that so by the delight of the ears the weaker minds may rise to the feeling of devotion. Yet when it befalls me to be more moved with the voice than the words sung, I confess to have sinned penally, and then had rather not hear music.

The Modern Devout shared Augustine’s unease and sought to combat potentially inappropriate use of music as he suggested, by emphasising the text of a song and not the melodic part for its own sake. This emphasis led, for example, to the prohibition of organs in churches and dormitories of monasteries belonging to the Chapter of Windesheim in 1464, on the grounds that singing in combination with organs led to far too much excitement: “Sicuti non admittimus organa in divino officio, ita nec in dormitorio causa excitationis.”

This view also had significant influence on the composition of polyphonic music in Modern Devout circles. While music might have been acceptable in encouraging the development of affect in meditation, the accompany text was responsible for ensuring that it was the right affect, and hence the text had to be clearly audible and understandable. As a result, polyphony in manuscripts of the Devotio Moderna was quite simple. If this was not so, “false affect” would result in improper and hence ineffective prayer. In this way meditative function influenced ideas about music in the sphere of the Devotio Moderna as well as the structure of the music itself.