- “Rebel in the Soul”

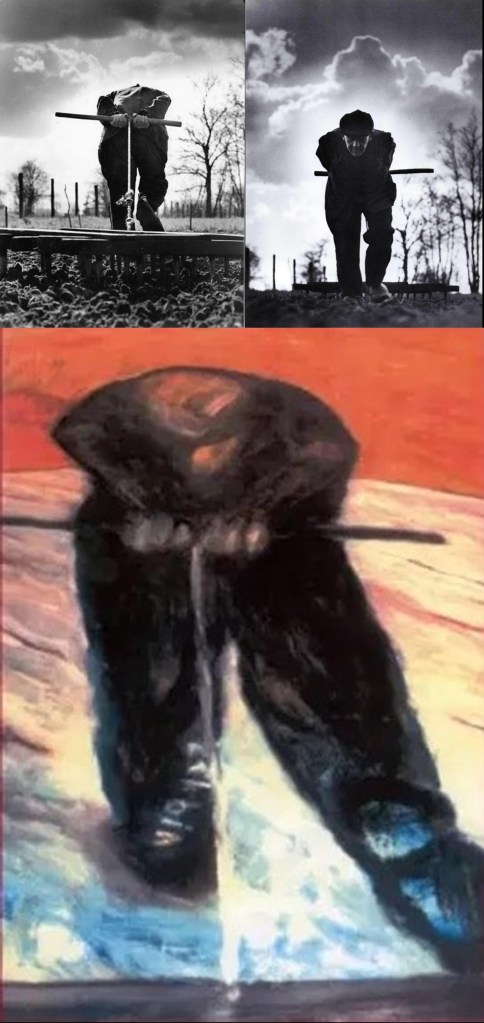

To start our Migration to the Spiritual Land of Peace , we look at an old text known as papyrus 3024 from the Berlin Museum, known as “Man arguing with his Soul” or the “Rebel in the Soul” we can perhaps study one of the earliest accounts of the confrontation with the ego.

– Rebel in the Soul: An ancient Egyptian dialogue between a Man and his Soul

This controversial text, that was meant for initiates at the threshold of the Ancient Egyptian Inner Temple, speaks to us with intriguing relevance to the problems of today. Taking the form of a dialogue between a man and his soul, this sacred text explores the inner discourse between doubt and mystical knowledge and deals with the rebellion and despair of the intellect at a crucial stage of spiritual development.

The first complete and consistent translation of the Berlin Papyrus 3024, which is thought to be nearly 4,000 years old:

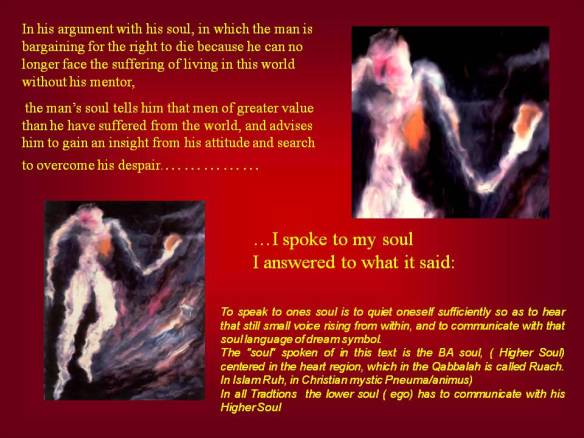

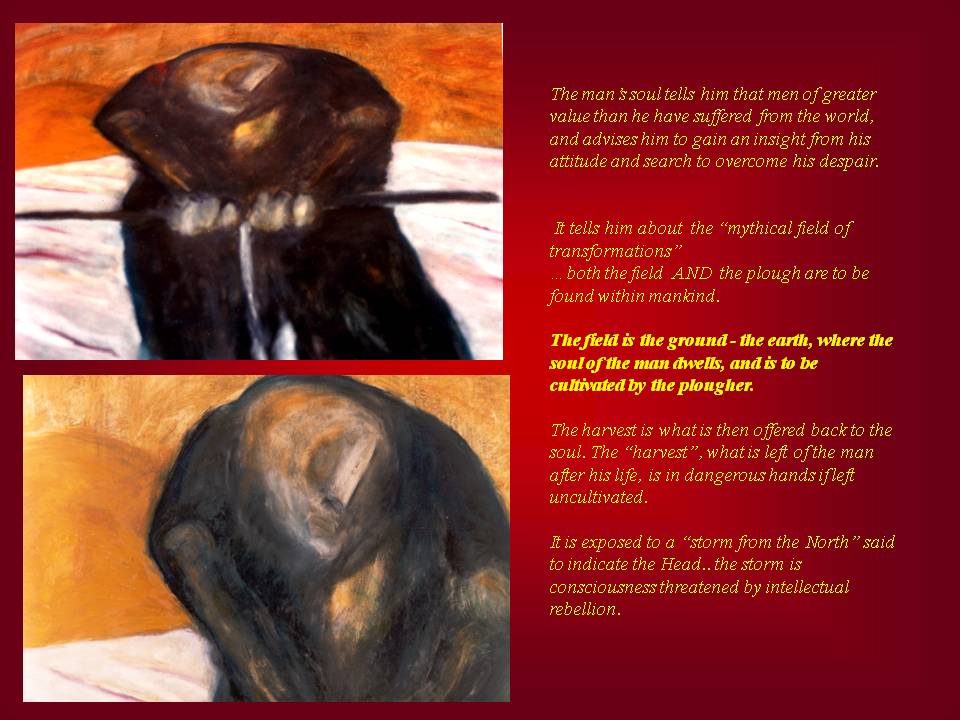

“The man’s soul tells him that men of greater value than he have suffered from the world, and advises him to gain an insight from his attitude and search to overcome his despair.

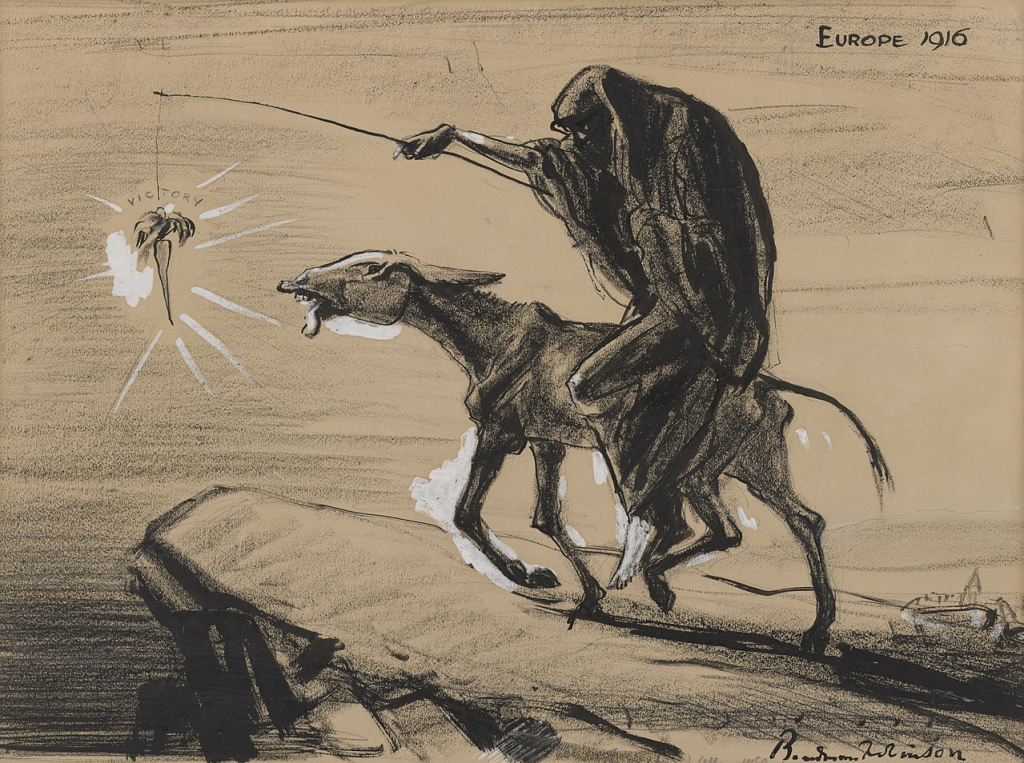

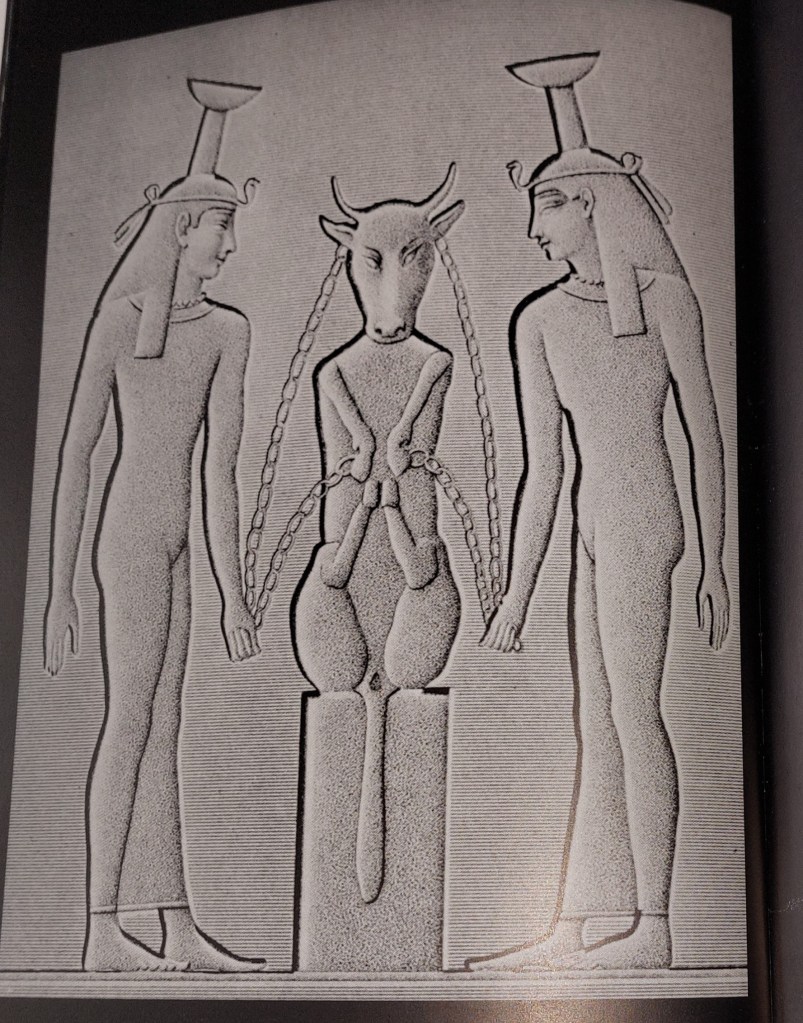

It is An Egyptian temple text, related with the God IAI, an aspect of the Solar God, the stubborn donkey. It shows the intellectual rebellion of our Ego.

“The stubborn, passionate, long-suffering ass is the perfect natural symbol of our rational personality. It bears, like the ass, the weight of all our suffering, and carries us through life. It is stubborn, selfish and refuses to go where we think we best…

Carrot and stick:

….Yet paradoxically, it is the same stubborn ass, and only the ass, that can carry the Rebel to salvation; mounted upon the ass, man is mounted upon his own rebellion. The ass is the father of all rebels, but also the carrier of redemption.”

In Ancient Egypt, Iai, the Great Ass, is the aspect of the Sun God with Ass’s ears. This is Osiris in his listening state; listening equalled wisdom to the Ancient Egyptians. The Book of the Gates depicts the progression of the sun through the night. The Twelve Hours of Night are depicted as regions of the Underworld. Each region is an Hour, and each Hour has its gate through which to pass. To pass, we must know the name of the gatekeeper, or guardian.

This is the same as identifying the layers of egos we each have within – an ego is what others might call one of the deadly sins, Pride, Envy, Greed…all those different aspects of the personality that can prevent us from progressing through the gates or stages of spiritual development. When we look inwardly at the aspects of our personality that rule or affect our lives, we need to recognise what is affecting our spiritual progress; if we learn to use it wisely and become its master, instead of it being master over us, we then recognise the Guardian of that Gate – can name the Guardian, and can “pass through the Gate”. Consciousness moves from Gate to Gate.

In the argument with his Soul, the man is bargaining for the right to die because he can no longer face the suffering of living in this world without his mentor. In Ancient Egypt, it was believed that a man and his Soul would be judged together in the afterlife; the Soul can make appeals on his behalf. So the man is arguing with his Soul to persuade it that killing himself is the correct thing to do, as he wants it to accept his reasons, and agree with him so that it will stay with him after death and make favourable appeals. However, his Soul has other ideas..

“I spoke to my soul that I might answer what it said:

To whom shall I speak today?

Brothers and sisters are evil and friends today are not worth loving.

Hearts are great with greed and everyone seizes his or her neighbor’s goods.

Kindness has passed away and violence is imposed on everyone.

To whom shall I speak today?

People willingly accept evil and goodness is cast to the ground everywhere.

Those who should enrage people by their wrongdoing

make them laugh at their evil deeds.

People plunder and everyone seizes _his or her neighbour’s goods.

To whom shall I speak today?

The one doing wrong is an intimate friend and the brother with whom one used to deal is an enemy.

No one remembers the past and none return the good deed that is done.

Brothers and sisters are evil

and people turn to strangers for righteousness or affection.

To whom shall I speak today?

Faces are empty and all turn their faces from their brothers and sisters.

Hearts are great with greed

and there is no heart of a man or woman upon which one might lean.

None are just or righteous and the land is left to the doers of evil.

To whom shall I speak today?

There are no intimate friends

and the people turn to strangers to tell their troubles.

None are content and those with whom one used to walk no longer exist.

I am burdened with grief and have no one to comfort me.

There is no end to the wrong which roams the earth.

When we consider the age of this text, from XII Dynasty Egypt (approx 1991-1783 BC), we can see that the nature of the woes and troubles of humankind have changed very little.

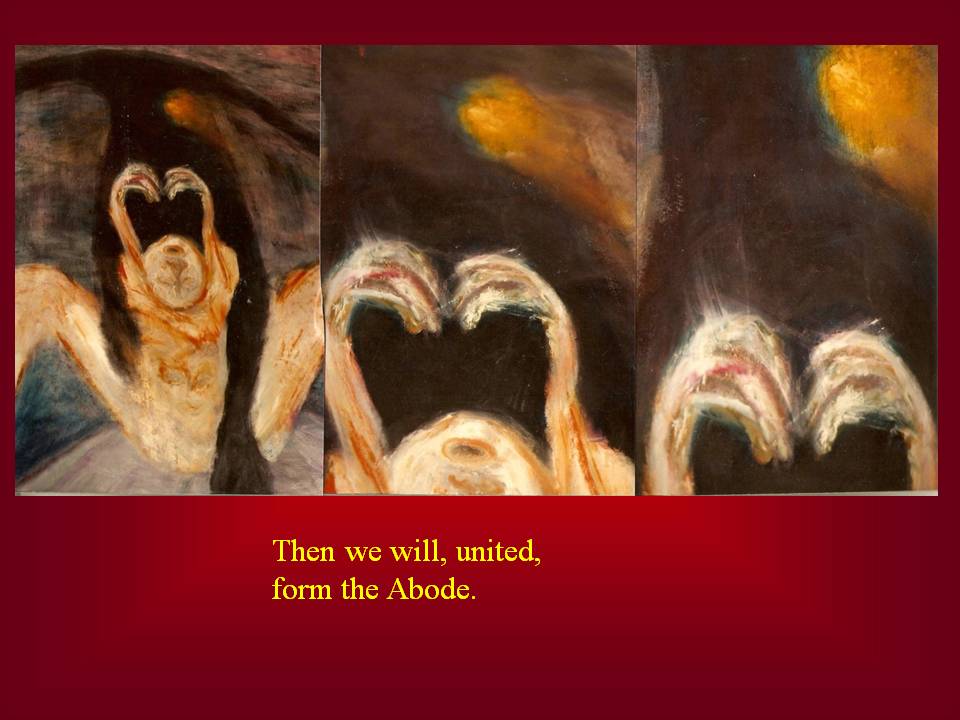

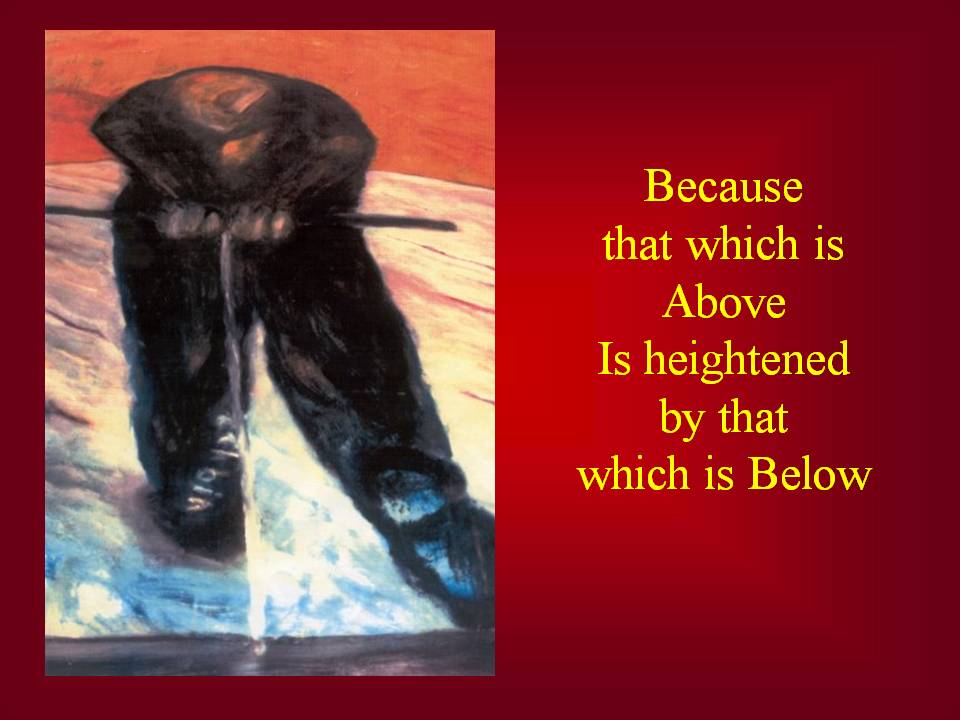

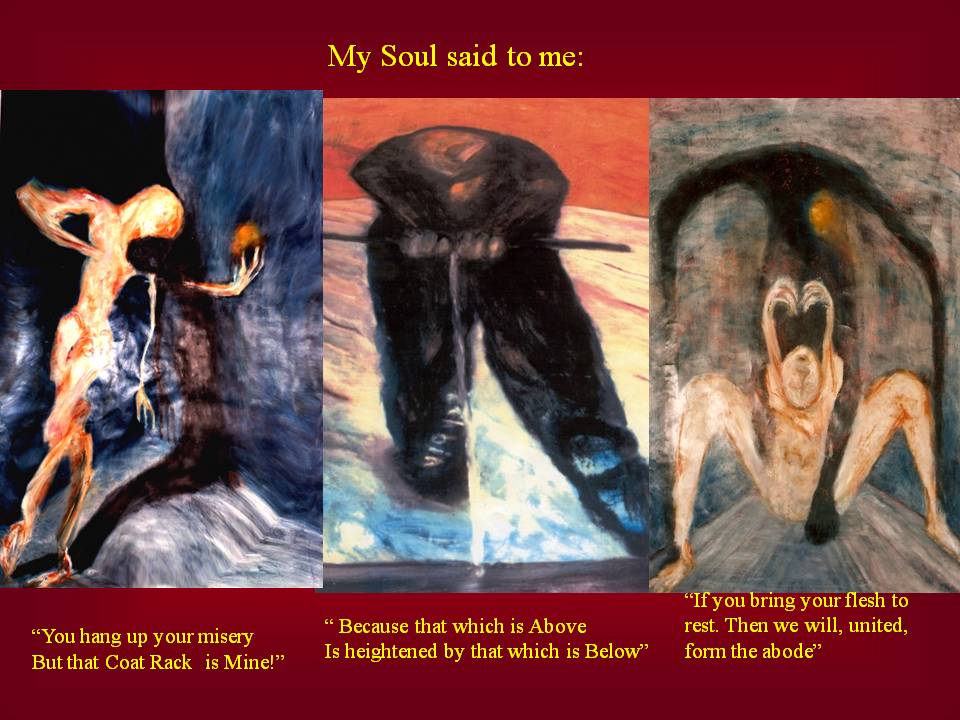

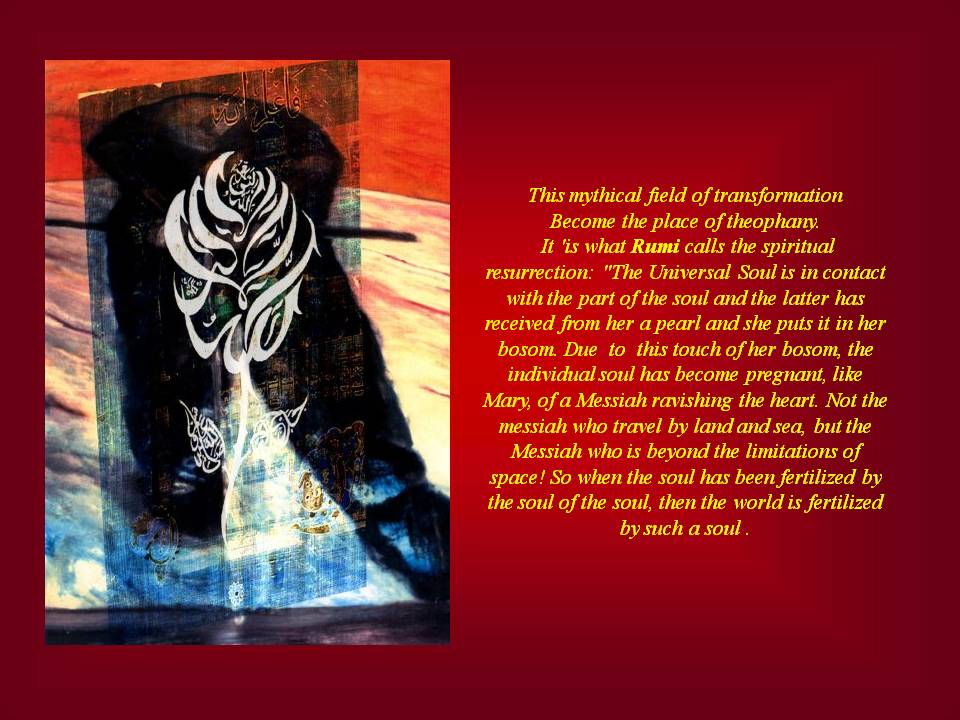

The man’s soul tells him that men of greater value than he have suffered from the world, and advises him to gain an insight from his attitude and search to overcome his despair. It tells him some allegorical stories – the first being the “mythical field of transformations”; both the field AND the plough are to be found within man. The field is the ground; the earth, where the soul of the man dwells, and is to be cultivated by the ploughman – the man must “cultivate” himself.

The harvest is what is then offered back to the soul. The “harvest”, what is left of the man after his life, is in dangerous hands if left uncultivated. It is exposed to a “storm from the North” said to indicate the Head (Reason); the storm is consciousness threatened by intellectual rebellion.

The man at this point in the story, when his Rebel/ego is arguing for survival, is not yet ready to let the wisdom of his heart rule his intellect, and this is symbolised by the crocodile. The man’s heirs, in the story he is told by his soul, are eaten by a crocodile whilst still in the egg, before they are fully formed, before they have lived, and will never realise their potential. See The Rebel in Soul by Bika Reed and here The Rebel in The Soul: The Wisdom of Ordinariness

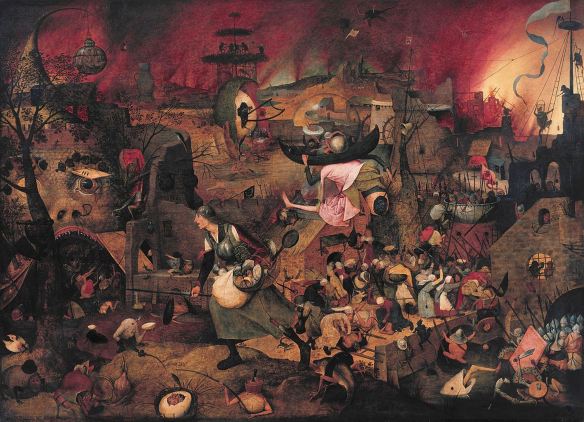

- Brueghel : the apocalypse within

The Fall of the Rebel Angels or The Archangel Michael Slaying the Apocalyptic Dragon, Dulle Griet or Mad Meg, and The Triumph of Death.All three panels are again the same overall size. The link is provided by the Apocalypse.

see also Analyse of the 3 paintings here

Notwithstanding the “predilection of his age for symbolism and allegory”, the eulogy of Ortelius that Bruegel ‘depicted many things that cannot be depicted’, the search for hidden truths, and the idea that this artist was deliberately obscure and cryptic, considering the dangers inherent in being openly critical, a degree of circumspection is only to be expected. With these three works, here we also have Bruegel’s major excursion into the world of Jheronimus Bosch. The first, the Rebel Angels, was at one time attributed to Bosch, the formal language of the second, Dulle Griet, is distinctly reminiscent of Bosch and the third, the Triumph of Death, has all the apocalyptic power of Bosch – and more; a landscape of death, one where the promise of redemption and resurrection is absent. God is nowhere to be seen. Or is it more we, our ego denies the existence of God?

Is the Message of Brueghel more like this: There is no God … But God? Recognising the eternal struggle in the soul of man between the sinful earthly being or nature, dominated by earthly wisdom, and the divine nature of God,Brueghel asks us a total submission.

The 1560s was no time for children’s games. Amused by each of these spectacles of humanity, people miss the underlying seriousness of Bruegel in everything he does. Bruegel transports us back over four centuries to a time when everyone looks to be having fun. Where did all the good times go? Within 50 years of this painting the European world appears to be have been struck by an epidemic of depression that plunged young and old into months and even years of morbid lethargy and relentless terrors. We seem to have been living with it ever since. The decline in opportunities for traditional pleasures is later reflected in John Bunyan’s march to a life free of fun. In Pilgrim’s Progress carnival is the portal to Hell, just as pleasure in any form, sexual, gustatory, convivial, is the devil’s snare. It seems that while the medieval peasant enjoyed the festivities as an escape from work, the Puritan embraced work as an escape from terror.

Progress came with a price. The new world had not yet made a Faustian pact with the Devil to gain its brilliant advances in science, exploration and industry but it had swept away some of the traditional cures for the depression that those achievements brought in tow.

But still, the old world had its own demons to fight. As visitors to the museums where this group of three pictures hang, smile, laugh even, and check those inventories of activity, the link between laughter and spirituality goes unnoticed.

The ability to laugh can help us through the best and worst of times. Its importance for our spiritual wellbeing is generally neglected.

Brueghel used the personnage of “Dulle Griet’ to express this kind of stubbornness as the stubborn donkey of the Egyptian papyrus from 4000 years ago. It shows the intellectual rebellion of our Ego.

Modern Man with all his “economical grow- energy” knowledge and scientifical research based on rebellion against his Soul, wants to find (without his soul) the solutions to all the problems he createdand is landed in an apocalyptic “theather” prophesying the complete destruction of the world.

an as stubbornness of the intellectual rebellion of our Ego so acting as “Whore of Babylon” discribed in the Book of Revelation.

Only by killing earthly wisdom and the lusts and properties in his soul would man enable Christ to be reborn within himself and be united with God, thereby restoring that `oneness’ referred to at the beginning of the Theologia Germanica:

- “Sin is selfishness:Godliness is unselfishness:A godly life is the steadfast working out of inward freeness from self:To become thus Godlike is the bringing back of man’s first nature”.

- Christ as Child in the Heart of the true believer.

What does love look like?

It has the hands to help others.

It has the feet to hasten to the poor and needy.

It has eyes to see misery and want.

It has the ears to hear the sighs and sorrows of men.

That is what love looks like.

Saint Augustine

In the 5 cirkels is written: “Gave van Barmhartigheid“: Gift of Mercy , “Gave van Genade’: Gift of Grace, “Gave des Levens” ( in the heart): Gift of Life, ” Gave van Medelijden”: Gift of Compassion, “Gave van sterkte“: Gift of strength.

- The Spiritual Message of Bruegel for our Times

Bruegel’s Philosophical Circle

Bruegel the man – as opposed to his paintings – remains more or less invisible to history. There is nothing written by him and, with one exception – Abraham Ortelius’ remarks in his Album Amicorum which will be discussed below – there is nothing by his contemporaries that provides a glimpse into his intellectual, psychological, philosophical or spiritual outlook. But those with whom he is known to have associated are among the most brilliant and outstanding men of their time; many of them were men of renown in the world. The writers, artists and religious thinkers whose names are linked with Bruegel were men of the humanist movement who, inwardly at least, rejected the politics and dogmatic rigidities of conventional religion in favour of a search for such philosophical and mystical truths as can be approached through methods of contemplative spirituality.

Like the gnostics before them they cultivated the art of complete inner freedom from conventions and preconceptions. Outwardly, like Lipsius, they could maintain the appearance of conformity, even if lightly. Others like Niclaes, the founder of the House of Love, more openly declared themselves „filled with God‟ and set themselves up as teachers, though Niclaes himself encouraged his followers to disguise their innermost convictions and let themselves be counted among the Church’s faithful.( A practice known as Nicodemism, a position whereby Christians could hide their dissenting beliefs while conforming to mainstream religious rituals).

Theirs was a form of gnosticism in that they gave priority to the action of knowledge granted by the Spirit over the disciplines of conformity to church regulations. It can be argued that they were students of esoteric Christianity and heirs of the Perennial Philosophy. Read more here

- Mutiny of the Soul

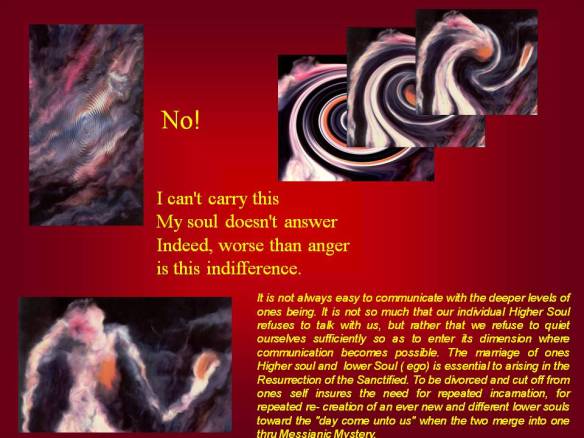

Depression, anxiety, and fatigue are an essential part of a process of metamorphosis that is unfolding on the planet today, and highly significant for the light they shed on the transition from an old world to a new.

When a growing fatigue or depression becomes serious, and we get a diagnosis of Epstein-Barr or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome or hypothyroid or low serotonin, we typically feel relief and alarm. Alarm: something is wrong with me. Relief: at least I know I’m not imagining things; now that I have a diagnosis, I can be cured, and life can go back to normal. But of course, a cure for these conditions is elusive.

The notion of a cure starts with the question, “What has gone wrong?” But there is another, radically different way of seeing fatigue and depression that starts by asking, “What is the body, in its perfect wisdom, responding to?” When would it be the wisest choice for someone to be unable to summon the energy to fully participate in life?

The answer is staring us in the face. When our soul-body is saying No to life, through fatigue or depression, the first thing to ask is, “Is life as I am living it the right life for me right now?” When the soul-body is saying No to participation in the world, the first thing to ask is, “Does the world as it is presented me merit my full participation?” Read More Here

- The Spiritual Land of Peace:

Look and behold: there is in the world a very unpeaceable Land and it is the wildernessed land wherein the most part of all impenitent and ignorant people do dwell and in which is, the first of all needful for the man; to the end that he may come to the Land of Peace and the City of Life and Rest. ( from Terra Pacis by Hendrik Niclaes of the Family of Love,)

The same unpeaceable land has also a City, the name of which they that dwell therein do not know, but only those who are come out of it, and it is named Ignorance.

The “Dulle Griet” as “whore of Babylon” , in the land of Ignorance by Brueghel:

Dulle griet is the representation of the Whore of Babylon living in a land of Ignorance.

The Whore of Babylon in the The Apocalypse Tapestry of Angers

The Whore of Babylon or Babylon the Great is a symbolic female figure and also place of evil mentioned in the Book of Revelation in the Bible. Her full title is stated in Revelation 17 (verse 5) as Mystery, Babylon the Great, the Mother of Prostitutes and Abominations of the Earth.

The word “Whore” can also be translated metaphorically as “Idolatress“.[1] The Whore’s apocalyptic downfall is prophesied to take place in the hands of the image of the beast with seven heads and ten horns. There is much speculation within Christian eschatology on what the Whore and beast symbolize as well as the possible implications for contemporary interpretation.

Dulle Griet is the model of modern man’s Rebellion against his soul and Anger against it. How can Dulle Griet find a way to calm her anger?

She can looks in the mirror and see herself,making more “selfies”, so seeing more anger as the portait of vanity of Hans Memling shows us. The lady see only more vanity The message of Memling is in his Triptych of Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation focuses on the idea of “Memento mori,” a Latin phrase that translates to “Remember your mortality.” Memling’s triptych shockingly contrasts the beauty, luxury and vanity of the mortal earth with images of death and hell. In the time of Breughel and in our times the message is that Vanity is not the solution. see: Nothing Good without Pain: Hans Memling”s earthly Vanity and Divine Salation

All Is Vanity by Charles Allan Gilbert (September 3, 1873 – April 20, 1929)

The phrase “All is vanity” comes from Ecclesiastes 1:2 (Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities; all is vanity.

Don’t change the world in hopes of changing yourself,

change yourself so the world changes because of you.

- In this land of Ignorance, for the food of men, there grows neither corn nor grass.

The people that dwell therein know not their original or first beginning; neither do they know from whence, or how, they came into the same. And moreover then, that they are altogether blind, and blind-born.

The forementioned city, named Ignorance, has two Gates. The one stands in the North, or Midnight, through the which men go into the city of darkness or ignorance.

This gate now, that stands to the North, is very large and great, and has also a great door, because there is much passage through the same; and it has likewise his name, according to the nature of the same city.

Foreasmuch as that men do come into Ignorance through the same gate, therefore it is named Men Do Not Know How to Do. And the great door, where through the multitude do run is named Unknown Error; and there is else no coming into the City named Ignorance.

The other gate stands on the one side of the City, towards the East or Spring of the Day, and the name is the Narrow Gate, through the which, men travel out of the city and do enter into the Straight Way which leads to Righteousness.

Now when one travells out through the same Gate, then does he immediately espie some Light, and that same reachs to the Rising of the Sun.

Here the symbolism, taking up the theme of the ‘bread of life’, i.e. spiritual nourishment, employs the images of ‘corn’ and ‘seed’ whose esoteric meaning was discussed earlier and which will be met again in the paintings by Bruegel of the Harvest and the Ploughman (Fall of Icarus).

The importance of spiritual nourishment – or rather the lack of it – is discussed in the section dealing with the Peasant Wedding Feast( in construction) (Marriage at Cana) where the lack of wine is shown to correspond, by rhetorical imitation, with famine imagery in the Old Testament where the sense is that of ‘famine for the word of God’.

‘Landscape With The Fall of Icarus.‘ It is the only painting Bruegel did with a non-Biblical mythological subject. W.H. Auden’s poem ‘Musee des Beaux Arts’ describes it:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just

walking dully a long; …

In Bruegel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash. the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky.

Had somewhere to go and sailed calmly on.

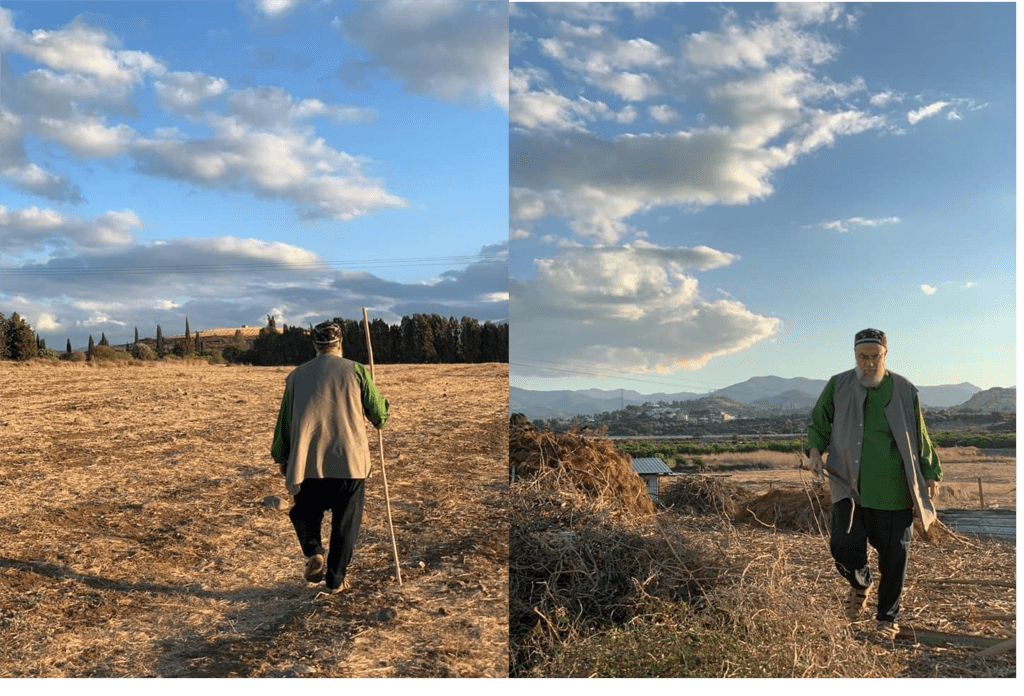

The painting shows Icarus, barely discernible, already submerged but for his legs. The ploughman in the foreground, the fisherman with his back to us, the shepherd leaning on his crook staring at the blank sky , his back to Icarus, the ship sailing away from Icarus to the horizon as the tones of earth and water fade toward the splashing pastels of a setting sun on the horizon, all underline Bruegel’s comment on the folly of human ambitions.

He had , as other Northern intellectuals, been familiar with Erasmus’ The Praise of Folly and the tradition of the “fool literature’ of the time, especially Brandt’s ·Ship of Fools’ (The Narrenschiff, 1494).

The painting represents a rendering of the German proverb: ‘No plough comes to a standstill because a man dies.’ As such, it establishes a continuity of myth and the times, but rather than make the event tragic he makes it inconsequential next to the mundane pursuits at hand. We come upon the actors in tableau , frozen as in a movie still about to come into action; the splash frozen too – creates a tension but one soon to be exhausted and consumed by the natural splendor of the sunset.

Here the painter has produced an eidetic effect: he has captured the event’s meaning while at the same time debunking its grandiosity.

The mundane elements of work and subsistence capture our attention, until as an afterthought we notice pale Icarus about to disappear. All of this is cradled in nature so that the painting becomes a pageant of indifference with a sense of cosmic irony. It is the scale of nature which makes the scene great though the actors in both harmony and tension with nature are unaware of the forces at work.

Hence, Bruegel’s ‘throwing away of the title ,’ a technique borrowed from the mannerists whom this painting debunks as well. Here Bruegel has entered a controversy over the desirability of Italian painting that raged among Flemish painters at the time. The realism of the Flemish plowman, anticipating in style and flavor Thomas Hart Benton’s rural apotheosis, the barely discernible corpse in the wooded area in the left middle ground , the theme of the fall, and the fragile make-believe classicized buildings moving toward the horizon to which all goes and from which everything comes, all point to a rejection of the hegemony of classicism, the debunking (relativizing) of mythologies superimposed from the outside, and an identification with indigenous Netherlandish elements represented by the peasantry.

- When we consider the age of this text ( The Rebel in the soul), from XII Dynasty Egypt (approx 1991-1783 bc), we can see that the nature of the woes and troubles of humankind have changed very little. This is where the text can also be read as a text of initiation.

The man’s soul tells him that men of greater value than he have suffered from the world, and advises him to gain an insight from his attitude and search to overcome his despair. It tells him some allegorical stories – the first being the “mythical field of transformations”; both the field AND the plough are to be found within man. The field is the ground; the earth, where the soul of the man dwells, and is to be cultivated by the ploughman – the man must “cultivate” himself.

The harvest is what is then offered back to the soul. The “harvest”, what is left of the man after his life, is in dangerous hands if left uncultivated. It is exposed to a “storm from the North” said to indicate the Head (Reason); the storm is consciousness threatened by intellectual rebellion.

The man at this point in the story, when his Rebel/ego is arguing for survival, is not yet ready to let the wisdom of his heart rule his intellect, and this is symbolised by the crocodile. The man’s heirs, in the story he is told by his soul, are eaten by a crocodile whilst still in the egg, before they are fully formed, before they have lived, and will never realise their potential.

The ‘heir’ in the egg symbolises what the cultivated man could become. Here we can see it as an unborn Akh.

The Man’s Ba is teaching him that The Great Ass, the ego and False Self, must be sacrificed to the crocodile. Unless this sacrifice is made, the man cannot travel further through the Hours of the Night to the light of dawn; he will never integrate with his mystical body and be re-born.

Anubis, the god of the Underworld, is also the god of helping us realise our full potential, as protector of the Soul in its journey through the Underworld.

Reed tells us:

“The Ancient Egyptian Myth which describes the birth of the redeemer, Anubis, gives us an insight into this dramatic turning, or birth into higher consciousness. In this myth, the jackal god is pursuing Seth, the Enemy of Light, who takes the form of a panther and escapes the dog.

But the mother dog, Isis, sees the panther and catches up. Terrified of the wild bitch, the panther transforms himself into the dog, his own pursuer. But Isis digs her teeth into his back. Caught, Seth cries, “Why are you pursuing this poor dog who does not exist?” The myth then says “And this is how he became. HE BECAME (IN PU) is the Egyptian name for Anubis, the first Priest of Osiris. The Redeemer (IN PU) only comes to life by seeing his own “inexistence”

In other words, we will only reach our full potential when we ‘pursue’ ourselves, and by doing this – the Work on the Self: cultivation, we will understand the need to sacrifice our false identity. Our ego will argue for its own survival, and this Rebel will put up the greatest fight, until we recognise it for what it is – a false non-existent self – and are born into higher consciousness, as our own “heir”.

The man shows he has understood:

In truth, he who is yonder will be a living god,

punishing the crime of him who does it.

In truth, he who is yonder will stand in the Bark of the Sun,

making its bounty flow to the temples.

In truth, he who is yonder will be a wise man,

who cannot, when he speaks, be stopped

from appealing to Re !

His Ba answers:

Throw complaint over the fence,

you my comrade, my brother!

May you make offering upon the brazier, and cling to life by the means you describe! Yet love me here, having put aside the West! [the West is where the deceased goin the Ancient Egyptian belief system]

But when it is wished that you attain the West, that your body joins the earth, then I shall alight after you have become weary, and then we shall dwell together!”