- Dante’s Pluralism and the Islamic Philosophy of Religion

This book shows that Dante’s project for the establishment of a peaceful global human community founded on religious pluralism is rooted in the Arabo-Islamic philosophical tradition–a tradition exemplified by al-Farabi’s declaration that “it is possible that excellent nations and excellent cities exist whose religions differ.” Part One offers an approach to Dante’s Comedy in the light of al-Farabi’s notion of the relation between religion and imagination. Part Two argues that, for Dante, the afterlife is not reserved exclusively for Christians. A key figure throughout is the Muslim philosopher Averroes, whose thinking on the relation between religion and philosophy is a model for Dante’s pragmatic understanding of religion. The book poses a challenge to the current orthodoxies of Dante scholarship by offering an alternative to the theological approach that has dominated interpretations of the Comedy for the past half century. It also serves as a general introduction to Dante’s thought and will be of interest to readers wishing to explore the Islamic roots of Western values.

All things walk on the Straight Path of their Lord and, in this sense, they do not incur the divine Wrath nor are they astray.

Ibn Arabi

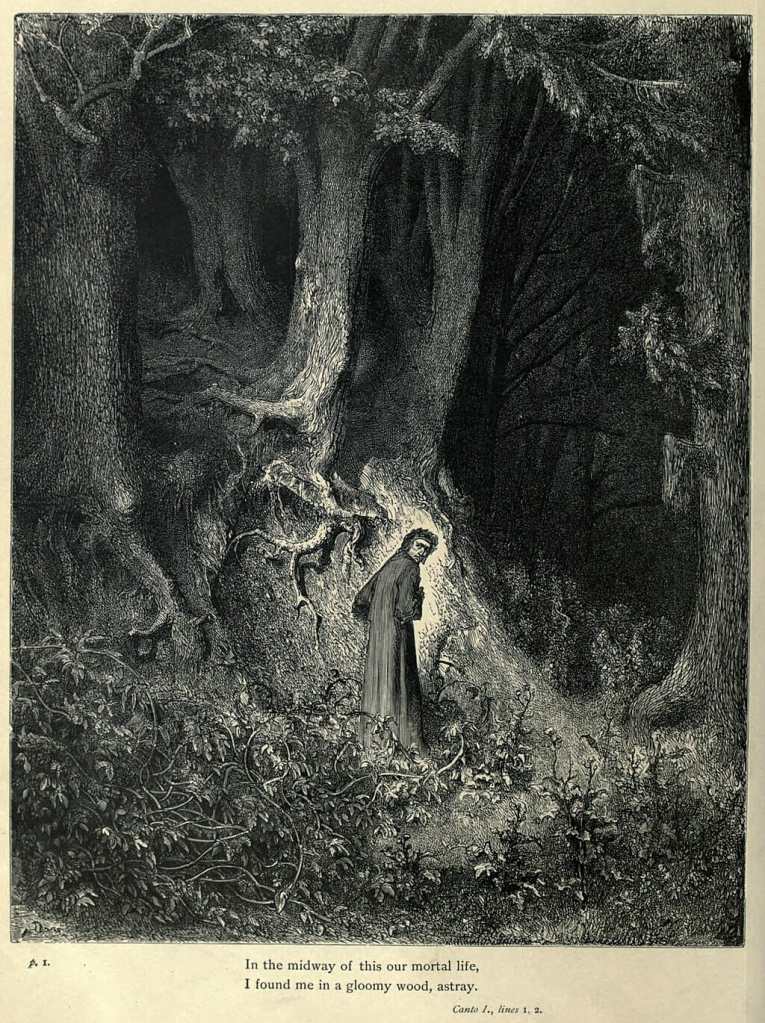

In the opening verses of the Comedy, Dante writes memorably of la diritta via, “the straight way,” the right path. A few verses later he speaks of la verace via, “the true way.”

In the middle of the journey of our life,

I came to myself in a dark wood,

for the straight way [la diritta via ] was lost. . . .

I cannot really say how I entered there,

so full of sleep was I at the point

when I abandoned the true way [la verace via].

(Inf. I, 1–3; 10–12)

What is this via, this way, straight and true, which Dante claims once to have abandoned and lost—the recovery of which will apparently be the matter treated in his poem?

The Christian tradition readily provides an answer, with the words of Christ himself: “I am the way [ego sum via], and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” ( John 14.6). Indeed, what could be more obvious than that the “straight and true way,” the right path that Dante abandoned, lost and regained and which his poem above all else exhorts us to find, is the path of Christianity?

It seems beyond doubt that the Comedy is primarily an imperative call to humankind: Thou shalt be Christian!

If this is so, then the Comedy might be construed as a threat to ways other than the Christian way, a denial of ways such as Islam, which from the beginning presents itself as the straight way. The Qur’an’s first sura recites a prayer to God:

“Show us the straight way, / The way of those on whom Thou hast bestowed Thy Grace, those whose (portion) is not wrath, and who go not astray” (1.6–7).

In Sura 42 God says to Muhammad: “Most surely you show the way to the right path” (42.52).

Dante’s Comedy and the Qur’an both open with the claim that the way to be mapped out is the straight way, the right path. Yet does this mean that each simply proclaims its own religious path as the single right way?

Dante tells us that he had lost and then found the straight way. The Qur’an tells us that Islam is the straight way. Can there be, on the question concerning the identity of the right path, any common ground between a Christian Comedy and the Islamic holy book? Or must we acknowledge that Dante and Islam are necessarily adversarial participants caught in a polemical clash of ways?

The Qur’an and Religious Pluralism

In the case of Islam, an answer presents itself: a plurality and diversity of ways is divinely ordained, for the Qur’an teaches that each and every human community, in every historical era, has been blessed with a truthful prophet: “To each nation we have given a prophet” (10.47). Muhammad does not offer a radically new revelation, a heretofore unheard of message (Qur’an 46.9: “Say: ‘I am not an innovation among the messengers’.”).

What is new is not the truth that Muhammad brings but rather the insistence that all peoples have always been brought the truth. Truth has been revealed to each community, throughout human history, in a way that is appropriate for the specific historical situations of each. Truth is not a special gift bestowed upon an elect nation, nor is it only first revealed at a certain midpoint of human history, following ages during which humankind was doomed to struggle in the dark. Rather, the Quranic teaching is that all human communities, everywhere and always, have been “reminded” by their prophets of what they ought already to know: to do good and avoid doing wrong—epitomized in the early Meccan revelations as charity to widows and orphans. Since each and every human community has been blessed with its own truthful prophet, the Qur’an encourages each people to embrace the truth (which amounts to the practice of “good works”) that is already there in its own tradition.

The Qu’ran’s most notable ecumenical verse tells us that each divinely revealed way is, in its own way, a right way:

For every one of you [li-kull-in: “unto each”] We have ordained a law and a way. Had God pleased, He could have made you one community: but it is His wish to prove you by that which He has bestowed upon you. Strive (as in a race) with one another in good works, for to God you shall all return and He will explain for you your differences. (5.48)

God does not merely tolerate, but rather he actively orchestrates and maintains religious and cultural differences. He does not wish for diversity to be overcome, here on earth, by the conversion of difference into identity.

God has intentionally created human ethnic, racial, national, and gender differences, not so that some groups would thus be marked as superior to others, but so that each would get to know others (“superiority” thus belongs not to groups but to individuals; it is a matter of one’s awareness of God and an honor that can be bestowed on individuals from any of the different groupings): “O humanity! Truly We created you from a male and a female, and made you into nations and tribes that you might know each other. Truly the most honored of you in the sight of God is the most Godconscious of you. Truly God is knowing, Aware” (49.13).

As Amir Hussain remarks, this passage “does not say that Muslims are better than other people, but that the best people are those who are aware of God.” The Qur’an envisions a world community that is locally diverse but also ultimately unified: all virtuous humans are part of God’s community insofar as they submit themselves to God’s guidance, to the truth that God provided for them in their own traditions and in their own languages: “Each messenger We have sent has spoken in the language of his own people” (14.4).

Although the essential revelation of the Qur’an is universal (“We never sent a messenger before thee save that We revealed to him, saying, ‘There is no god but I, so serve me’ ” [21.25]), this one universal message is always made manifest in a particular culturally specific form. God, who delights in cultural and racial diversity (“Among His other wonders are the creation of the heavens and the earth and the diversity of your tongues and colors”; 30.21), has given each particular historical people the message in its own vernacular—so that the truth is never something alien to a community, never something imposed by one human community upon another – as Ibn Arabi puts it:

God has sent “to each and every community an envoy who is one of their kind, not someone different to them.”

The message is always there in the tradition of every vernacular. Despite their differing ways, all virtuous believers—all who heed the teachings that God has given them in their own religious tradition and in their own language—will end up returning to God, and all in the end will be saved: “Believers, Jews, Sabaeans and Christians—whoever believes in God and the Last Day and does what is right—shall have nothing to fear or to regret” (5.69).

The religious limit that divides “us” from “them”—although it remains in place here on earth as testimony to God’s wondrous unlimited creativity—is in the final analysis effaced.

There was in the medieval Islamic exegetical tradition a debate concerning the referent of Qur’an 5.48’s li-kull-in (“unto each”; see above: “For every one of you [li-kull-in] We have ordained a law and a way, etc.”).

A minority of commentators took “unto each” to mean “unto every Muslim”; they thus took the verse to mean: “For every Muslim [yet not for non-Muslims] we have ordained a law and a way.” The diversity at stake here then is internal to Islam—a matter of the multiplicity of Islamic sects, which, according to a famous hadith (one of the canonical “Traditions” concerning the sayings and deeds of the Prophet) are said to be seventy-three in number. The aim of this minority reading of Qur’an 5.48 would then be to lend scriptural support to the legitimacy of pluralism within the Islamic community as a whole. Such a reading would be in accord with the non-canonical hadith: “The disagreements of my community are a blessing.” Here one might mention the position of the eminent scholar al-Baghdadi (d. 1037 AD), who maintained that any teachings that fit in the framework of the seventy-three sects, no matter how “heretical” they may appear in the eyes of others, have a legitimate place in the Muslim community. He cites an earlier thinker, al-Ka‘bi (d. 931 AD), who goes even farther, deeming legitimate anything taught by anyone who affirms the Prophethood of Muhammad and the truth of the Prophet’s teaching: “When one uses the expression ummat alislam [the community of Islam], it refers to everyone who affirms the prophetic character of Muhammad, and the truth of all that he preached, no matter what one asserts after this declaration.”

The thrust of this position is that, within the Islamic community, there are no doctrinal limits—that anything taught by a Muslim is by definition authentically “Islamic.”

But the majority of medieval exegetes understood the referent of Qur’an 5.48’s “unto each” to include Muslims and non-Muslims alike—so that the verse is understood not to be directed exclusively to the Muslim community but rather to a variety of religious communities. In accordance with the commentary of the great historian and exegete al-Tabari (d. 923 AD)—who showed that taking “unto each” to mean “unto each Muslim” makes no sense in itself and fails to respect the context of surrounding verses—every major medieval commentator took Qur’an 5.48 to be God’s declaration of ecumenical pluralism. Some of these took the referent of “unto each” to be the so-called People of the Book, a category that comprised Jews, Christians, and Muslims, but which, as Islamic civilization moved farther east and encountered more peoples in possession of scriptural traditions, was expanded to include Zoroastrians, Hindus, and Buddhists. On this reading, the verse teaches that all virtuous individuals belonging to communities that profess scripture-based religions will in the end be counted among those in Paradise. An even more “liberal” interpretation was implied by commentators such as al-Zamakhshari (d. 1144 AD) and al-Baydawi (d. 1286 AD), for whom the referent of “unto each” is all humans, regardless of their religious identities.

The thrust of this interpretation is that, when it comes to the matter of the afterlife, there are no religious limits dividing cultures or groups of peoples that will be “saved” from those that will be “damned”: all virtuous humans will be accorded their place in Paradise.

The Plurality of Paths

Does this recognition of a plurality of right paths work both ways? If the Qur’an mandates that Muslims acknowledge the truth and rectitude of Dante’s Christian way, does the Comedy in turn insist that Christians acknowledge the legitimacy of non-Christian ways?

Our initial response must be negative, since the Comedy’s first twelve lines do indeed give the impression that there is a single right path, one and only one “straight and true way” to the desired destination. But the next two stanzas cast everything in doubt:

But when I had reached the foot of a hill,

where the valley ended

that had pierced my heart with fear,

I looked on high and saw its shoulders clothed

already with the rays of the planet

that leads us straight [dritto] on every path.

(Inf. I, 13–18)

Doubt is cast on the very idea of la diritta via—the idea that one can speak, using the singular, of “the straight way,” for here Dante calls the sun “the planet that leads us straight on every path” (in Ptolemaic cosmology, the sun was considered one of the planets). If the sun is such a guide—if Dante is neither mistaken nor lying—then any and every path is potentially a right one.

Those guided by the sun are always going the right way, regardless of which way they happen to be going. We learn in line 18, which recalls with its dritto the diritta via of line 3, that every illuminated way is “the straight way.”

We ought not gloss over the universalist implications of this verse— perhaps one of the most significant in the entire poem—simply because such implications do not fit our image of a Dante for whom “rectitude” is an accolade that can, in the final analysis, be granted solely to the Christian way.

Is there not an intolerable contradiction? How can Dante first speak of “the straight and true way,” then immediately follow this with talk concerning the inevitable rectitude of every way under the sun?

Read further Dante’s Pluralism and the Islamic Philosophy of Religion

48- Allah is He Who sends the winds, so they raise clouds, and spread them along the sky as He wills, and then break them into fragments, until you see rain drops come forth from their midst! Then when He has made them fall on whom of His slaves as He will, lo! they rejoice!

49- And verily before that (rain), just before it was sent down upon them, they were in despair!

50- See, then, the tokens of Allah’s Mercy: how He revives the earth after it is dead. Verily He is the One Who will revive the dead. He has power over everything.

You can also read: