- BRUEGEL THE ELDER AND THE HIDDEN TRADITION

By Sir Richard Temple at The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts

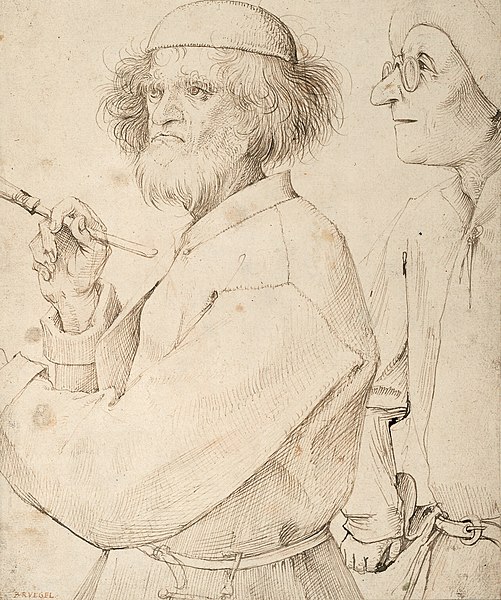

The late paintings of Peter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525 – 1569) are full of symbolism and allegory whose meaning has been widely and differently interpreted. Some see Bruegel as a gifted, humorous peasant, others as a satirist and political commentator and yet others as a Renaissance humanist and mystic. There is no consensus on the significance of the paintings and hardly any documents to help the historian.

This thesis considers Neoplatonic humanist ideas at the heart of the Renaissance in Italy and in Flanders in the 16th century, relating them to the historical continuum known as the Perennial Philosophy. This concept is little understood today and this work traces its history and demonstrates that it was widely, if not universally, accepted in the Hellenistic era and in the Renaissance.

It also considers the tradition of religious mysticism in Germany, the Netherlands and Flanders throughout the late Middle Ages that led up to the Reformation and points out that this movement is also an expression of the Perennial Philosophy, citing the works of Meister Eckhart, the Rhineland mystics and the schools that came out of the Devotio Moderna.

The work considers the esoteric, ‘heretical’ school called the Family of Love that claimed among its adherents a number of highly illustrious artists, thinkers and politicians. Such men as Christoffe Plantin, Abraham Ortelius and Justus Lipsius spurned the religious turmoil of the period and rejected Catholics, Lutherans and Calvinists alike in favour of an inner mystical state they called the ‘invisible church’. They were close to Bruegel, bought his paintings and, it cannot be doubted, shared his thought.

While there are no surviving documents to prove Bruegel’s personal connection with the Familists, the weight of circumstantial evidence, especially when seen in the context of the Perennial Philosophy, is compelling. However, it is the paintings themselves that open comprehensively and convincingly to an esoteric interpretation – once one has the key that unlocks their meaning. This thesis provides that key and leads the reader through an analysis of seven of Bruegel’s last paintings.

The Introduction consists of two sections; the first summarises the discoveries and

opinions of scholars and art historians during the last seventy years and their differing

and often incompatible views as to Bruegel‟s religious and social status and the

significance of his art. The second section analyses in some detail his painting The

Numbering at Bethlehem along the line of esoteric ideas and symbolism that will be

developed throughout the whole work .

The form of the ideas of this thesis could be illustrated by a picture of three concentric circles of which the outer would be the Perennial Philosophy – what Renaissance thinkers regarded as the body of truth drawn by the ancients from their knowledge of the cosmos and which, like the universe, has no external boundary. In writing about the Perennial Philosophy I have cited Plato and Hellenistic and Renaissance Neoplatonists as well as writers of the 20th-century, among whom are Ananda Coomaraswamy and René Guénon and writers associated with their ideas; I have also quoted the theosophist W. Thackara.

Within this is the second circle containing aspects of the Perennial Philosophy that found expression in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance periods and which culminated in Antwerp in the 16th-century. What may at first appear to be diverse influences are drawn from Renaissance „paganism‟, the mysticism of Meister Eckhart and his followers as well as „gnostic‟ or „heretical‟ schools such as the Adamites with whom Hieronymus Bosch was associated. At the centre of all this – in the innermost circle – is Bruegel or, rather, his paintings, for the man himself is more or less silent and invisible. Yet the testimony of the later paintings is like a kernel containing the wisdom of the Perennial Philosophy.

The paintings are there for all to see and yet their colours, forms and narratives are a veil

– albeit a veil of great beauty – that covers a high order of knowledge. They are,

therefore, esoteric.

In fact the form of the ideas set out here is necessarily linear but we can remind ourselves that the right to speak of the ultimate truths of Man and the universe was regarded in the 16th-century as traditionally belonging to the realm of prophets, poets, mystics and artists.

Such men spoke in multi-layered symbols and their vision is not limited to mens and

ratio only.

Part I is mainly concerned with the now partly forgotten language and ideas in

which such philosophical questions were considered.

Chapter 1, then, sets out the case for the Perennial Philosophy as it has been understood in the 20th century with quotations from, among others, Aldous Huxley, Rufus Jones, W. Thackara and William Quinn who set out what they regard as its basic tenets. Among ancient writers cited are Dionysius the Areopagite and Duns Scotus Erigena generally regarded as the agents through whom the Perennial Philosophy passed to the West.

Introduced here are the concepts of mysticism and esotericism – themes which naturally run throughout the whole work – which are presented to the reader in the light of traditional understanding.

Chapter 2 goes to the Greek sources of the European branch of the Perennial Philosophy: namely Plotinus and his followers the so-called Neoplatonists – among them Porphyry and Iamblichus. Outlines of Plotinian cosmology and psychology are given in some detail since they are the basis of so much of medieval and Renaissance spirituality.

Chapter 3 considers aspects of early Christian thought in the light of perennial ideas.

Here we find the early appearance of tension between the forces of institution and the

forces of spiritual freedom. Origen, the father of the allegorical method of interpreting

sacred scripture, is cited in connection with esoteric levels of symbolism in the Gospel.

The idea of gnosis is considered and the eventual isolation of various gnostic sects that

came to be regarded as „heretics‟.

Chapter 4 discusses these problems further and emphasises the importance the mystical and esoteric aspects of spirituality both within and outside the doctrines imposed by the Church. It traces the origins of 2nd-century gnostic sects whose beliefs and teachings survived into the 16th-century. Read here Chapter 1 to 4

Chapter 5, drawing on the writing of Rufus Jones, traces the historical continuity of

perennial philosophical thought and practice from antiquity up to the eve of the

Reformation. It considers the mystical tradition, inherited from Dionysius and passing

through Eckhart and the Rhineland mystics, that produced the Imitatio Christi and the Theologica Germanica. This chapter stresses the importance of contemplative prayer or meditation and shows how this practice was the basis of spiritual movements, under the name of the Devotio Moderna, such as the Friends of God and the Brotherhood of the Common Life.

Chapter 6 looks at the Perennial Philosophy acting on Neoplatonist humanists and

mystics of the Italian Renaissance. Reference is made to Edgar Wind‟s work on

Renaissance esotericism and Andrea Solario‟s portrait of Christoforo Longoni is analysed in the light of the idea of self-knowledge as a spiritual exercise and as a central concept of this thesis.

Chapter 7 brings us to immediate and direct influences on Bruegel. These were free thinking humanists and mystics who occupied the no-man‟s-land between Catholics, Lutherans and Calvinists; men like Sebastian Franck, Dirck Volckertz Coornhert and Abraham Ortelius were adherents of the „invisible church‟ where God was understood as „an event in the soul‟ which could be independent of external forms, rites and doctrines. Many of them, such as Ortelius, Christophe Plantin and perhaps Justus Lipsius belonged to the sect known as the Family of Love whose leader, Hendrik Niclaes, was the author of the mystical allegory Terra Pacis that recounts the journey from the „Land of Ignorance‟ to the „Land of Spiritual Peace‟. Bruegel was closely associated with, if not a full member, of this group.

Chapter 8, drawing on the writings of Herbert Fränger, considers the art of Hieronymus

Bosch and his association with the movement known as the Brethren of the Free Spirit among whom was an extreme group called the Adamites for whom Bosch painted The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Common aspects of both Bosch and Bruegel are discussed. This chapter discusses the direct relationship in sacred tradition between art and meditation and cites an example of Tibetan culture. It ends with a discussion of Abraham Ortelius‟ remarks concerning Bruegel; in particular his observation that he „painted what cannot be painted‟. Read Here chapter 5 to 8

In Part II, six of Bruegel‟s late paintings are looked at in detail with the aim of assigning

their message to one of the three stages of man‟s possible spiritual evolution.

The Adoration of the Kings

The Massacre of the Innocents

Chapter 9 deals with The Adoration of the Kings and The Massacre of the Innocents

whose psychological commentary calls us to see the truth of the human condition – that

human beings, enmeshed in the demands of temporal life, do not see that they live in spiritual darkness and ignorance. Read Chapter 9

The Road to Calvary

Chapter 10, analysing The Road to Calvary, shows that it not only illustrates the

consequences of man‟s stupidity but at the same time it indicates that hope of redemption lies in the evolution of consciousness.

The Harvesters

The Fall of Icarus

This possibility is further developed in the symbolism embedded in The Harvesters and The Fall of Icarus where the work associated with plowing the land and harvesting the corn is an allegory of spiritual work. Read here Chapter 10

The Peasant Wedding Feast

Finally, in Chapter 11, it is argued that the painting known as The Peasant Wedding

Feast is in fact Bruegel‟s mystical commentary on The Marriage at Cana – the

miraculous transformation, symbolised by the changing of water into wine, which takes place when God and man are united. According to Matthew Estrada, whose ideas influence parts of the chapter, this event is sometimes known as the alchemical wedding.

But the circumstances of this process are mysterious in that they do not take place in the material world. The main burden of the thesis is to investigate that „other world‟ to which Bruegel had access and where, according to spiritual authorities, spiritual transformation takes place. Read here Chapter 11 and conclusion

Appendix

Text of TERRA PACIS and commentary relating to ideas of the Perennial Philosophy and

to paintings by Peter Bruegel. Read Here

- The Spiritual Message of Bruegel for our Times

- The Way of Self-Knowledge

A basic tenet of the Perennial Philosophy is that the world – the cosmos – has its counterpart in man. Man is the miniature of the universe; man is the microcosm: ‘As above, so below’,( Hermes Trismegistus, The Emerald Tablets) ‘in earth as it is in heaven’. (Matt. vi, 10)

But Man, according to traditional ideas, is excluded from his proper place in the cosmic scheme because of what allegory calls ‘Adam’s sin’ which condemns him to lead a false life, a life away from his rightful inheritance.

This is the central difficulty of the human condition, a riddle that calls man to awaken to the reality of his situation and become a seeker of truth.

If he hears this call he will learn that he must undergo an inner transition or transformation and that this has to take place before he can once again participate in real life.

This transformation – sometimes called rebirth – is very difficult to achieve and costs a man dearly because it takes place in opposition to everything he values in material life; but that is an illusory life which he mistakes for the other.

The seeker of truth begins to see the contradiction between what he is at present and what he is called to become and, seeing this, he cannot avoid suffering. If he has the courage to continue and if, in spite of suffering and other difficulties, he remains on the true path, he will eventually come to what tradition refers to as ‘dying to oneself’ – in Sufism, ‘die before you die’

and, in Christianity, the esoteric meaning of this ‘death’ is symbolised in the allegory of the Cross which is why we are told that it leads to eternal life. (See Devotio Moderna)

If a person sees only as far as the literal and moral meaning in the narratives of sacred literature and has no sense of the mystical or esoteric meanings to which symbolism and allegory refer, then nobody can convince him otherwise.

But if, desiring these yet higher meanings, he studies the world and himself impartially he may come to see the truth about what his life is and what it could be. The aim and the constant companion of the soul’s journey on the mystical path is, therefore, self-knowledge.

The seeker who undertakes a programmed study of himself – his interior self that traditional literature refers to as the heart – awakens to a new and unknown world. ‘The heart is only a small vessel, yet dragons are there, and lions, there are poisonous beasts, and all the treasures of evil, there are rough and uneven roads, there are precipices; but there too is God and the angels, life is there and the Kingdom, there too is light ...’ St Makarios the Great (fl. circa 400). Quoted in J. A. McGuckin The Book of Mystical Chapters, Meditations on the Soul’s Ascent from the Desert Fathers and Other Early Christian Contemplatives. Boston and London, 2002.

- Application of the Sacred Tradition in practice

In PETER BRUEGEL THE ELDER AND ESOTERIC TRADITION , we have explored the idea that traditional sacred art and literature are vehicles for transmitting knowledge of what philosophers associated with the Perennial Philosophy regarded as eternal truths. We have also examined the idea that such knowledge comes veiled in symbolism and allegory. Here a further stage needs to be looked at in considering how the action of such knowledge can be a transforming and even transubstantiating event in the life of a person.

For actual transformation a person has to come out from the ambience of ideas and into the spiritual battleground within himself or herself where those ideas are applied in practice.

Sacred texts and images refer allegorically to the series of ascending steps that are specific to the spiritual journey. In literature classic examples are St John Climacus’ the Ladder of Divine Ascent and Walter Hylton’s, The Ladder of Perfection.

The image of the ladder is also found in art, among notable examples is the 12th-century Byzantine icon preserved at St Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai. The principle of ascending steps or stages in the mystical path reflects the idea of the cosmic hierarchy that Christian mystical Tradition inherited from Plotinus. see The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843–1261

The implication of all the texts – and Hendrik Niclaes’ Terra Pacis, which will be discussed below, is typical – is that a preliminary phase of the journey is the period when the seeker awakens to the reality of his present situation. This is a long and difficult stage in which the seeker studies, and begins to know intimately, every illusion and pretence that sustains his or her present life in order to become free from them.

These last words are emphasized because they throw light on an important aspect of the group of paintings by Bruegel that will be discussed later in this thesis. The idea is proposed that the path of self-knowledge through spiritual exercises is a central, though perhaps hidden, element in Bruegel himself and in his art. Rightly conducted spiritual exercises create a heightened state of consciousness or ‘attentive awareness’ that corresponds to the Greek proseche – a frequently recurring term in the Philokalia – or the state of sati or ‘mindfulness’ in Buddhist terminology.

When developed, this quality liberates the seeker from the entanglements of his personal psychology (the thoughts and feelings with which he blindly and habitually reacts to the world around him) and allows him to see objectively.

Note:The most important work of this tradition and one of the most precious books of Christian spirituality is the Philokalia. Read here the Philokalia, and the Philokalia on the prayer of the Heart. Other classical works of the Hesychast tradition include The Way of a Pilgrim and The Pilgrim Continues His Way,

The capability to see what is and, therefore, to know truth is the attribute of a high degree of interior development in a man. According to St Isaac the Syrian: ‘He who succeeds in seeing himself is better than he who has been graced with seeing the angels’.( Philokalia)

Or, to quote from the Sufi tradition, we find Rumi writing in the Mathnawi, ‘The vision in you is the only thing that matters …Transform your whole body into vision, become seeing, become seeing.’ (Djalậl ed-Din Rumi, Mathnawi, VI, 1463, 4) Read here the Mathnawi.

It is the contention of this thesis that Bruegel was a man of wisdom in the perennial tradition. It will be shown that the means available to Bruegel and his circle in Antwerp in the 1550s were the teachings of the group that can be regarded as inheritors of the Perennial Philosophy; they are known as the Family of Love or the Familists. This inheritance was the tradition of esoteric Christianity surviving in the West that has been outlined above.

Antwerp in the first half of the 16th century was the leading mercantile city in Europe; a metropolis of world class at every level, ‘the Manhattan of the sixteenth-century’. It had a dazzling life of arts and letters and had been the home of many illustrious figures, among them the great Erasmus. A few Bruegel scholars, Tolnay among them, acknowledge the humanist influences on Bruegel. The French historian and writer on heresy Stein-Schneider sees a Cathar connection but he is unsympathetic to the idea of Bruegel’s connection to an esoteric school. Claessens and Rousseau briefly acknowledge Auner’s remarks. But no documents – other than his paintings – exist that throw direct light on what might have been Bruegel’s inner life and what role he played in the intellectual life of his contemporaries. No one has investigated in depth traditional mystical ideas in their relationship to Bruegel and to the idea that the Familists and the humanists reflected principles of the Perennial Philosophy.

- The Family of Love Lineage of the Family of Love

The Family of Love, whose ideas are central to Bruegel‟s intellectual and religious outlook, was not an isolated phenomenon and can be shown to be a link in the chain of schools – more or less hidden – stretching alongside the more visible history of Christianity in Europe. This essay has followed the sequence traced by Rufus Jones and others beginning with the primitive Church itself, mysticism in classical literature and in the Church Fathers followed by Dionysius the Areopagite in the 6th century and Duns Scotus Erigena in the 7th. Later, in the 12th century, these teachings were to be a source for various mystical groups most of whom were violently persecuted as heretics, these include the Waldenses, who may have been related to the Cathars, and the followers of Amaury (or Amalrich) de Bene. In the 13th century we find the Franciscan brotherhoods (Beghards) and sisterhoods (Beguines) who were later to be transformed into the ‘Brethren of the Free Spirit‟.

The teachings of Meister Eckhart and the Rhineland Mystics in the 14th century opened the way to the loosely structured ‘Friends of God‟ and the Theologica Germanica. Later still, in the Netherlands, the New Devotion( or Devotio Moderna) and the Brotherhood of the Common Life were to represent the tradition that Jones calls the ‘invisible church which never dies, which must always be reckoned with by official hierarchies and traditional systems and which is still the hope and promise of that kingdom of God for which Christ lived and died’.

From there it was passed to such men as Sebastian Frank, Volkerz Coornhert and Hendrick Niclaes. Today some people would see the Quakers among its descendants.4 Both its apologists and its detractors variously wrote about the Familists in the 16th and 17th centuries, the latter often in violent and abusive terms. They seem to have been more or less forgotten until the beginning of the 20th century when historians rediscovered them.

Note: See more here on English dissenters prior to and during the civil war/revolution in England as well as during the Interregnum. We view the information broadly, incorporating a variety of religious and social movements and viewpoints that were active at levels of state, and among the élites and common folk.

- The Hiël Group

Terra Pacis and other books by Hendrick Niclaes were printed in secret by his disciple Christophe Plantin (1520-1589), the leading printer and publisher of his day and a member of a small group within the Familist Movement known as the Hiël Group. It was under the direction of Jansen van Barrefelt who was later to break with Niclaes and start (in 1569) the Second House of Love. He took the name Hiël (in Hebrew, „God Lives’) presumably because of its symbolism associated with the rebuilding of Jericho. ( 1 Kings, 16 – 34:In Ahab’s time, Hiel of Bethel rebuilt Jericho. He laid its foundations at the cost of his firstborn son Abiram, and he set up its gates at the cost of his youngest son Segub, in accordance with the word of the Lord spoken by Joshua son of Nun. )

According to scholars, members of this group represented a much higher stratum of society and numbered literary and scientific men of renown among them’. Research indicates that, apart from Plantin, among other participants were Benito Aria Montano (1527-1598), chaplain to Europe’s most powerful monarch, Phillip II of Spain.

Montano was in Antwerp to oversee the printing of the Polyglot Bible, the illustrated, multilingual publication in eight volumes that was to immortalize Plantin’s name. He was renowned as a scholar and played a significant role in the high politics of the day.9 Among other members of the group were the orientalist Andreas Masius and the cartographer and pupil of Mercator, Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598). Another was the Stoic and humanist scholar, painted by Rubens and Van Dyke, Justus Lipsius (1547–1606). All of these men knew Pieter Bruegel in one way or another and at least two of them, Ortelius and Plantin, are known to have been close friends of his.

- Bruegel’s Philosophical Circle

Bruegel the man – as opposed to his paintings – remains more or less invisible to history. There is nothing written by him and, with one exception – Abraham Ortelius’ remarks in his Album Amicorum which will be discussed below – there is nothing by his contemporaries that provides a glimpse into his intellectual, psychological, philosophical or spiritual outlook. But those with whom he is known to have associated are among the most brilliant and outstanding men of their time; many of them were men of renown in the world. The writers, artists and religious thinkers whose names are linked with Bruegel were men of the humanist movement who, inwardly at least, rejected the politics and dogmatic rigidities of conventional religion in favour of a search for such philosophical and mystical truths as can be approached through methods of contemplative spirituality.

Like the gnostics before them they cultivated the art of complete inner freedom from conventions and preconceptions. Outwardly, like Lipsius, they could maintain the appearance of conformity, even if lightly. Others like Niclaes, the founder of the House of Love, more openly declared themselves „filled with God‟ and set themselves up as teachers, though Niclaes himself encouraged his followers to disguise their innermost convictions and let themselves be counted among the Church’s faithful.( A practice known as Nicodemism, a position whereby Christians could hide their dissenting beliefs while conforming to mainstream religious rituals).

Theirs was a form of gnosticism in that they gave priority to the action of knowledge granted by the Spirit over the disciplines of conformity to church regulations. It can be argued that they were students of esoteric Christianity and heirs of the Perennial Philosophy.

- Abraham Ortelius

A key that may help to unlock the mystery of Bruegel‟s relationship to such men is provided by Abraham Ortelius. He and Bruegel, together with Christophe Plantin who would become Europe‟s leading printer and publisher, were close contemporaries, all born within a few years of each other, and as young men incorporated into of the guild of St Luke in Antwerp.13

Abram Ortel was a native of Antwerp who latinised his name, according to the custom of the day, as Abrahamus Ortelius, is known to the world as a geographer, the some time associate of Mercator and for his publication of the Theatrum Orbis Mundi, the world‟s first atlas, published in 1570. We learn that ‘his youthful reading was very much that of the humanist-in-the-making; that is, it reflected the humanist‟s conviction, supremely expressed in the life and work of Erasmus, that the wisdom of Greece and Rome and the teaching of Christianity constituted, when examined, a seamless fabric. ‘Saint Socrates!‟ Erasmus had famously exclaimed – to emphasize the unbroken line that stretched from Greek philosophers to the Church Fathers‟.

Humanism is a broad category of thought that defies precise definition as a philosophical system. It comprises the thought of such men as Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Emanuel Chrysoloras, Cardinal Bessarion, Lorenzo de Medici, Politian, Pico della Mirandola, Erasmus and Thomas More who translated the works of classical authors and in whose styles they themselves wrote. Some were accused of paganism or semi-paganism but the rigor and energy of their scholarship gave them great power and influence and many worked under (and for) the Church’s authority. It inspired much of the reform movement of 14th-, 15th- and 16th-century Europe. Much of humanism can be seen as the exoteric aspect of the Perennial Philosophy.15

Early in his life Ortelius himself had an experience of Christ which was to remain with him, strong and lucent, throughout its length. He had taken Christ into himself just as, a century and a half before, Groote’s Devotio Moderna movement had advised all true believers to do, and only among those who believed in the supreme importance of this process, of an inner life dwarfing all dogmas and disputes, all hierarchies and rites, would Ortelius feel truly at home spiritually. And such a group Ortelius found: the Family of Love under the charismatic leadership of Hendrik Niclaes.

From remarks noted by friends and from the contents of his library, Ortelius was deeply influenced by Sebastian Franck (1499-1542), a one-time Catholic priest, then a Lutheran pastor who later became an „independent and highly influential spiritual teacher’. He stressed „the longing for oneness with God [who was] so frequently impeded by doctrines and church obligations … [He] was an enemy of all religious division between believers … Franck had his roots in those two works … Imitation of Christ ( read here) and Theologica Germanica ( Read here).He was also well versed in writers at the foundation of the Perennial Philosophy, often referring to Plato, Plotinus and Hermes Trismegistus as „his teachers’ who had „spoken to him more clearly than Moses did’.

Ortelius, a man of deep spirituality, together with his close friend and colleague Christophe Plantin – and there is no evidence to suggest that Bruegel was not with them – joined the movement known as the Family of Love in the late 1540s.

For Ortelius in particular the movement had roots in earlier traditions in which he had himself partaken. It’s clear from the books he owned and read and from his letters which abound in references to the spiritual life – that Ortelius was steeped in the pietistic, quietist Netherlandish religious tradition the roots of which are to be found in the Devotio Moderna (Modern Devotion) movement founded in 1397 by Geert Groote … The movement’s influence was far-reaching, not least because of the effect of the extraordinarily popular Imitation of Christ (1518) of Thomas à Kempis, its fullest written expression, which itself relates to roughly contemporaneous works such as the Theologica Germanica. The Devotio Moderna was a major factor in Netherlands social life mainly through schools. Axiomatic to Groote’s belief was a reformed system of education more humanistically inclined than the dominant one.

The Brethren of the Common Life, as Groote’s followers were called, combined attention to classical language and literature with a somewhat anti-intellectual approach to religion, dismissing the tortuously complicated arguments of scholasticism. (Erasmus was Brethren-educated). Common Life schools appealed to a newly prosperous, level-headed and influential middle-class with little time or regard for the rarefied hair-splitting of orthodox theology.

A practical outer life and a developed inner one sit well together; the one can safeguard the other, can give it appropriate, even encouraging conditions in which to flourish. Such a cast of mind could well mean that you stayed within the Catholic fold but developed a private spirituality, and this was the position of many a Family member.

- Sebastian Franck

Franck switched his religious allegiance several times led by the combination of his humanist passion for freedom with his mystic devotion to spirituality. He came to believe that God communicates with individuals through the fragment of the divine assigned to every human being. He felt that this communication had to be direct and unfettered and wrote that “to substitute Scripture for the self-revealing Spirit is to put the dead letter in the place of the living Word‘. He believed that the only true church is an entirely inward matter comprising what he called, in a phrase echoing the Gnostics of the second century, the ‘invisible church’:

“The true Church is not a separate mass of people, not a particular sect to be pointed out … not confined to one time or place; it is rather a spiritual and invisible body of all the members of Christ, born of God, of one mind, spirit and faith, but not gathered in any one external city or place.

It is a fellowship, seen with the spiritual eye and by the inner man. It is the assembly and communion of all truly God-fearing, good-hearted, new-born persons in all the world, bound together by the Holy Spirit – a communion outside which there is no salvation, no Christ, no God, no comprehension of Scripture, no Holy Spirit and no Gospel. “I belong to this fellowship. I believe in the communion of Saints, and I am in this church, let me be where I may, and therefore I no longer look for Christ in ‘lo heres‟ and ‘lo theres‟.

For Franck the church of the spirit is an event within the soul; ‘an entirely inward event‟. Love is the one mark and badge of fellowship in the True Church. External gifts and offices make no Christian, and just as little does the standing of a person, or locality, or time, or dress, or food, or anything external. The kingdom of God is neither prince nor peasant, food nor drink, hat nor coat, here nor there, yesterday nor tomorrow, baptism nor circumcision, nor anything whatever that is external.

As a result of his study of the early Church Fathers Franck declared in, a letter:

I am fully convinced that, after the death of the apostles, the external Church of Christ, with its gifts and sacraments, vanished from the earth and withdrew into heaven, and is now hidden in spirit and in truth, and for these past fourteen hundred years there has existed no true external church no officious sacraments.

The true and essential word of God is the divine revelation in the soul of man. It is the prius of all scripture and it is the key to the spiritual meaning of all scripture.

Elsewhere Franck declares “ his dissatisfaction with ceremonies and outward forms of any sort, his refusal to be identified with any existing empirical church, his solemn dedication to the invisible church, and his determination to be an apostle of the spirit‟. Franck, dismissing the Lutheran, Zwinglian and Anabaptist cults of his day, all of which had large followings, foretells the birth of a church that will dispense with external preaching, ceremonies, sacraments and office as unnecessary, and which seeks solely to gather among all peoples an invisible, spiritual church in the unity of spirit and faith, to be governed wholly by the eternal invisible word of God, without external means, as the apostolic church was governed before its apostasy, which occurred after the death of the apostles.

Franck is “without question saturated with the spirit of the mystics; he approves the inner way to God and he has learned from them to view this world of time and space as shadow and not as reality.‟ Franck had translated Erasmus‟s In Praise of Folly and Agrippa‟s Vanity of Arts and Sciences and, in the tradition of such works and of mysticism, he is very harsh on the role of ‘reasoning’: which is ‘a good guide in the realm of earthly affairs. It can deal wisely with matters that effect our bodily comfort and our social welfare, but it is “barren” in the sphere of eternal issues. It has no eye for realities beyond the world of three dimensions‘.

- Dirck Volckertz Coornhert

If Franck, who was a generation older, was a favourite writer of Ortelius, his friend and contemporary was Dirck Volckertz Coornhert (1522-1590): artist, historian, philosopher, humanist and writer, also a pupil of Franck. Coornhert worked as principal engraver for the great Maarten van Heemskerck together with his pupil, Philip Galle who would later become a famous engraver in his own right and who would work closely with Bruegel. For art historians, Coornhert’s importance lies in the fact that he inspired artists whose designs he engraved – among them Heemskerck, Adriaen de Weerdt and the young Goltzius – to create images that expressed his own philosophical outlook, Many of the themes of his prints are paralleled in his literary work. A similarly significant intellectual and philosophical symbiosis seems to have existed between Galle and Bruegel.

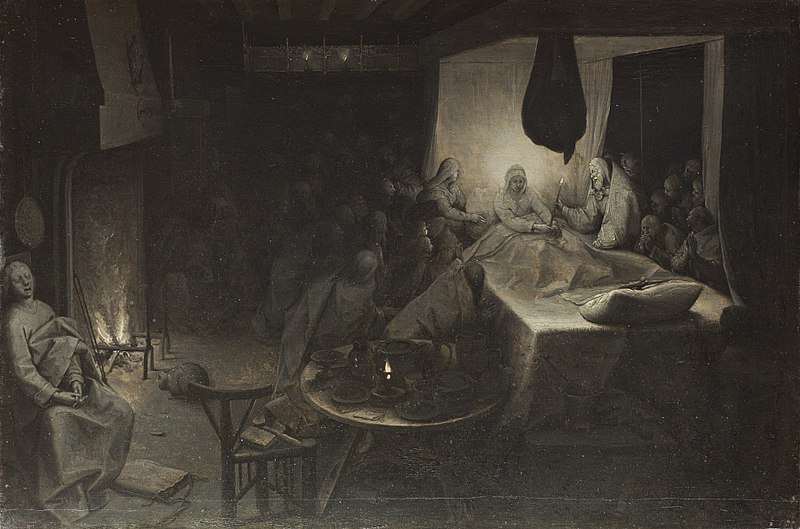

The names of Galle, Bruegel, Coornhert, Montano and Ortelius all come together in the story of the engraving of The Death of the Virgin.

The painting, a haunting work in grisaille that hangs today at Upton House near Banbury, had originally belonged to Ortelius. A large number of Bruegel’s drawings were done specifically for the popular market in engravings but his paintings were private commissions and were not produced as editions of prints. The print of The Death of the Virgin is an exception and, even so, there was never a popular edition. Some years after Bruegel’s death Ortelius engaged Galle to produce a very limited edition intended for members of the intimate circle that had constituted the Hiël group. A letter (dated 1578) exists from Coornhert to Ortelius thanking him for his copy and in 1591 Arias Montano wrote having received his. (See Manfred Sellink in Nadine Orenstein, Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Drawings and Prints, New York: The Metropolitan Museum, 2001, pp. 258-261

Coornhert openly acknowledged a spiritual outlook formed under the influence of Franck and, like his mentor, devoted energy to translating great masterpieces of the perennial tradition including Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy, Cicero’s On Duties, Erasmus’ Paraphrases of the New Testament and Homer’s The Odyssey.

At first, as a humanist, he was passionately committed to the cause of freedom of religious thought and opposed the rigidity and doctrinaire stance of Calvin. Later he came under the influence of Franck as well as other spiritual reformers such as Hans Denck and Sebastian Costellio and received from them formative influences which turned him powerfully to the cultivation of inward religion for his own soul and to the expression and interpretation of a universal Christianity‘. Coornhert makes a distinction between the forms of institutional religion, which he calls „outer or external religion’, which he allows as a preparatory stage and „inward religion’ which is the establishment of the kingdom of God in men’s hearts. “Only God has the right to be master over man’s soul and conscience; it is man’s right to have freedom of conscience”. With his intransigent defense of tolerance, even toward nonbelievers and atheists, the Dutch Catholic humanist and controversialist Coornhert made a substantial and permanent contribution to the early modern debate on religious freedom.

Rejection of the institutionalized reform movements on the basis of their new dogmatism and formalism … motivated the believers in a more “inward” spiritualized faith. Like the reformers, Spiritualists advocated free Bible research, but as a result of the notion of a direct personal relationship with God – and individual approach that we also find in Erasmus – they attach great importance to an unimpeded access to the Spirit of the individual.

At the same time they tend to minimize the importance of “externals”: ceremonies, sacraments, the church, often also the supreme authority of the Bible, for they consider the Spirit of prior significance; the Bible without the Spirit becomes a “paper pope” as Frank put it.

The same author points out that while Erasmus and humanism were a significant influence on men like Sebastian Franck, spiritual seekers were also influenced by late-medieval mystical traditions found in Eckhart and Tauler. Voogt acknowledges the importance for 16th century exponents of radical dissent of the anonymous Theologia Germanica (German Theology) which they frequently used and quoted from.

Henry Niclaes, founder of the Family of Love was profoundly influenced by this work (and by Thomas â Kempis‟ Imitation of Christ). He, and his main disciple (and later rival) Barrefelt, felt attracted to the Theologia’s theme of the return to a Platonic oneness and of the freedom of the will. They embraced the notion, found in this small book, that incarnation continued after the Ascension of Christ. This incarnation – known among Familists as Vergottung (godding) – takes place, they believed, whenever the spirit entered the individual.

One element of the Theologia that does leave a strong imprint on Coornhert … mostly through the mediation of Sebastian Frank … was the idea of the invisible church, vested in the hearts of true Christians wherever they may be found.

- Christophe Plantin

Born in France, Plantin later settled in Antwerp where, through a combination of superb skill as a typographer and good business sense he became the leading printer and publisher of his time. In 1562 he was indicted for his involvement with the Familist leaders Hendrik Niclaes and Jansen Barrefelt and was obliged to flee from Antwerp. He succeeded, however, in dissipating the suspicions against him, and it was only after two centuries that his relations with the Familists, or „Famille de la Charité’ came to light, and also that he printed the works of Barrefelt and other „heretics’.62

The editor of the Polyglot Bible with whom Plantin worked closely in Antwerp was the scholarly Spanish Benedictine monk, Benito Arias Montano. The last volume contains essays, illustrations and maps by Montano that show the wide range of his scholarship as a philologist, an expert in Oriental languages, an antiquarian, a geographer and as a specialist in the practice of visualizing and tabulating knowledge. ‘He designed his maps both as study aids and as devotional-meditative devices. Moreover, the maps reflect his wider philosophical outlook, according to which Holy Scripture contains the foundations of all natural philosophy. Montano’s case encourages us to re-examine early modern Geographia sacra in the light of the broader scholarly trends of the period.’ Montano was also part of the Family of Love circle around Barrefelt.

The revolutionary changes in religious thought that were taking place in the 16th century did not stop with Luther and Protestant theology. The movement that has come to be called the Radical Reformation sought to go much further. Its leading thinkers, according to Jones, ‘were not satisfied with a programme that limited itself to the correction of abuses, an abolition of medieval superstitions, and a shift of external authority … They placed a low value on orthodox systems of theological formulation … insisting that a person may go on endless pilgrimages to holy places, he may repeat unnumbered “paternosters”, he may mortify his body to the verge of self-destruction, and still be unsaved and unspiritual; so too he may “believe” all the dogma … he may take on his lips the most sacred words … and yet be utterly alien to the kingdom of God, a stranger and a foreigner to the spirit of Christ.‘

The radical reformers brought a new and fresh interpretation of God who, they declared, ‘is not a suzerain, treating men as his vassals, reckoning their sins up against them as infinite debts to be paid off at last in a vast commercial transaction only by the immeasurable price of a divine life, given to pay the debt which had involved the entire race in hopeless bankruptcy‟.

In the same way, they would not accept the Almighty as a sovereign, ‘meting out to the world strict justice and holding all sin as flagrant disloyalty and appalling violation of law, never to be forgiven until the full requirements of sovereign justice are met and balances and satisfied‟. These extreme reformers would not accept that God‟s Salvation could be thought of in such ways. They insisted that he is a personal God ‘who is and always was eternal Love‟ and who has to be found through a personal relationship. Here Jones formulates an idea that would be echoed in more or less the same words a generation later by Coomaraswamy when he says that ‘Heaven and Hell were for them inward conditions, states of the soul‟. In other words Heaven and Hell are not to be put off into the afterlife but are encountered and experienced as the actual psychological realities of each present moment.

- Esoteric nature of the House of Love and Terra Pacis

the House of Love was essentially an esoteric movement, a 16th century manifestation in Europe of the Perennial Philosophy, and that the writings of its founder, Hendrick Niclaes, can be interpreted in its light. Niclaes‟ vision of the ‘Land of Ignorance‟ where everything goes ‘wonderfully absurdly‟ is not so far from the contemporary (or near contemporary) writings of Erasmus, in particular In Praise of Folly, or Rabelais who repeatedly focused on dogmas that fetter creativity, institutional structures that reward hypocrisy, educational traditions that inspire laziness, and philosophical methodologies that obscure elemental reality.

But it would be a mistake to regard Terra Pacis as satire for it is, in fact, esoteric allegory.

To follow the esoteric idea it is necessary to distinguish between two realities: the material world in time and the spiritual world in Eternity. (c. f. Eckhart: „Why celebrate the Birth of Christ in time, if I do not celebrate his birth in eternity, in me‘.

The formulaic, “pagan” idea sees a separation between spirit and matter, but the universe of Plotinus, and of Dionysius the Areopagite, shows us a graded world that, descending, understands spirit gradually becoming less spiritual and more material; while, ascending, it sees matter becoming gradually less material and more spiritual.(Dionysius the Areopagite, Mystical Theology and Celestial Hierarchies)

Pure spirit and pure matter only “exist” at the extreme poles of the universe: the level of “The Absolute” and the level of “Absolute non-being”.

This hypothesis takes on another meaning in the light of the idea that man is the universe in miniature, the microcosm. It means that all gradations of matter exist in him, though some are so fine as to be imperceptible to the physical senses and, it could be said, are not of the material world.

Man’s lack of self-knowledge (lack of inner self-knowledge) leaves his psychological and spiritual worlds in darkness. Never entering within himself, he has only the vague or distorted and inaccurate ideas about his inner universe. Esoteric and gnostic teachings hold that, for ‘light’, or ‘love’, or ‘Christ’ to enter into a man, certain conditions have to be prepared through the help of methods of contemplation and prayer that lie at the heart of all religions – often partly buried or hidden behind external forms and rituals. These methods can create what the Hindu masters call an ‘inner structure‟ and what, in the Philokalia, is called ‘the house of spiritual architecture‟. Read here the Philokalia, and the Philokalia on the prayer of the Heart. Other classical works of the Hesychast tradition include The Way of a Pilgrim and The Pilgrim Continues His Way,

- Esoteric symbolism in the Gospel

Many commentators hold that an esoteric aspect of prayer can be understood from the words of Jesus in the gospel. (Matt. 6:6. ). Before discussing these in detail it will be helpful to remember that the entire passage, chapters 5, 6, and 7 of St Matthew‟s Gospel, begins with a symbolic description hinting that this part of the teaching is esoteric. ” And seeing the multitudes, [Jesus] went up into a mountain; and when he was set, his disciples came unto him. And he opened his mouth and taught them.(Matt. 5:1)

The movement away from “the multitudes‟ and the fact that he “went up a mountain‟ esoterically symbolizes Jesus ‟ withdrawal from the level of worldliness and multiplicity to a spiritually higher place where very few could follow him, i.e. only the disciples and not the crowd. It is while still in this exalted state of being that he tells them: “When thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy father which is in secret; and thy father which seeth in secret shall reward thee‟. (Matt. 6:6)

The Greek έισελθε ειç τό ταμείον σοσν και κλείσας την θύραν σοσ προσεσζαι τώ πατρί σοσ τώ έν τώ κρσπτώ (literally: „enter into your hidden room and having shut your door pray to the father, the one in secret‟) lends itself to mystical interpretation. For example the “hidden room‟ corresponds to the”„house of spiritual architecture‟; the term “father‟ in Neoplatonism is a synonym for”„The Absolute‟, the centre of the universe and origin of all. As far as the individual is concerned the “father which is in secret‟ is unknown to all other parts of the self, and cannot be known by the “normal‟ process of thought, the process called by Hendrik Niclaes “knowledge of the flesh‟. The early 4th-century mystic, Aphrahat the Persian puts it thus:

From the moment you start praying,

Raise your heart upwards

And turn your eyes downward.

Come to focus in your innermost self

And there pray in secret to your heavenly father.

The text fragments discussed below are from the English translation of 1649. Hendrik Niclaes‟ Terra Pacis is a classic in the genre of allegorical mystical literature that describes, in images taken from the visible world, events whose reality is in the invisible world. These events refer, often directly and intimately, to the adventures of the human soul – indeed, our own soul – on its evolutionary journey.

Examples of the genre are found throughout all ages and may be amongst the oldest and most enduring literature known to humanity. The 3rd-century philosopher Plotinus leaves us in no doubt that, for him at least, Homer’s Odyssey is just such an example “For Odysseus is surely a parable to us…it is not a journey of the feet‘. Plotinus, The Enneads, p. 63,

- Terra Pacis IntroductionTerra Pacis, The Land of Spiritual Peace was first published in Antwerp in 1574 by Hendrik Niclaes, the founder of the mystical religious sect known as the Family of Love or the House of Love (Domus Caritatis, famille de la charité, huis der liefde, etc.). The title page gives the author as H. N. This is in fact an abbreviation for Helie Nazarenus (Elijah the Nazarene), the name bestowed on him for his mission as a prophet. He founded the Family of Love in the early 16th century and it attracted converts in quite large numbers in Brabant, Flanders, Friesland, Holland, Antwerp and, later, in France and England, where it seems to have petered out around 1690 after long harassment and condemnation by both the Crown and the Church.

Last published in English in 1649 and little read after the end of the 17th century, Terra Pacis has the status of a lost classic more or less unknown today. The commentary aims to show that a symbolism can be discerned in the text that corresponds, in part, to the hidden sense in Bruegel’s art and that such spiritual allegories are part of a continuous tradition dating at least as far back as the origins of Christianity.

In the introductory ‘Epistle’, Niclaes makes it clear that his intention is to ‘know the Truth in the Spirit’.

His only concern is with the inward, spiritual life though, as he explains, spiritual truth cannot be directly communicated to those who have not the necessary special preparation.

The realities of the Kingdom of God are so far from anything we can perceive with the physical senses – which he calls ‘knowledge of the flesh’ or ‘wisdom of the flesh’ – as to be incomprehensible to those living in the material world.

The term “knowledge of the flesh”is not, of course, a coy way of referring to sex. Its meaning is psychologically precise and refers to the fact that, at the earthly or material level, our thoughts, attitudes and outlook on the world depend on information from the physical senses.

Science, or what René Guénon calls ‘scientism’, and much of Western thinking are founded on the rational mind’s ability to weigh, measure, analyse and classify matter perceived by the senses, so it is difficult for us today to conceive of a faculty of knowing that is situated “beyond reason and beyond sense-perception” .

Niclaes says towards the end of his text ‘The Kingdome of God of Heavens is come inwardly in us’. T

To those of us who have yet to make the ‘journey’ from the psychological or spiritual condition allegorised as the ‘Land of Ignorance’ to the inner state represented by the ‘Land of Spiritual Peace’ he can only speak, as Christ did to the ‘multitude’, in parables.

For I will open my mouth in similitudes, reveal and witness the riches of the spiritual heavenly goods as parables, and figure forth in writing the mystery of the Kingdom of God or Christ according to the true beeing.

I look and behold: to the children of the kingdom (of the Family of Love of Jesus Christ) it is given to understand the mystery of the Heavenly Kingdom; but to those that are therewithout, it is not given to understand the same. For that cause all spiritual understandings do chance to them by Similitudes, Figures and Parables.

He goes on to say that the use of ‘parables and similitudes’ is provisional. Later, they will not be necessary, but only after the occurrence of an event that he calls ‘a new birth’.

What has been said so far uncovers a theme consistent with the perennial Philosophy and, as this author intends to demonstrate, common to the ideas implicit in Bruegel’s paintings.

Man’s inner world is, or rather should be, and could be, the microcosm, the image in miniature of the universe; but in his present state, Man fails to reach this in himself and his inner world is in disorder.

There are different stages, or states of being, in the journey from chaos and darkness towards true life.

Various traditional literary images describe the human condition before the journey begins. For example, the Gospel refers to ‘blindness’ and ‘deafness’.

Saint Anthony the Great defining ‘intelligence’ implies that we are not even worthy to be called men;

‘He alone can be called a man who can be called intelligent (true intelligence is that of the soul), or who has set about correcting himself. An uncorrected person should not be called a man.

Note: Pieter Bruegel (Temptation of St Antony):

Hieronymus Bosch – The Temptations of St. Anthony:

Brueghel the Younger Temptation of St. Anthony:

Jan Brueghel The Elder – The Temptation of Saint Anthony:

Pieter Bruegel I the Younger (1564-1638):The Temptation of Saint Anthony:

The Temptation of Saint Anthony Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-1569)

Legends of Anthony Abbot relate how the pious early Christian, forsaking society, journeyed into the wilderness to seek God. Anthony appears twice in this painting; in his foreground retreat, he resists the Devil’s manifold temptations.

After failing to yield to the evil lures, he is shown again being physically tortured while carried aloft by demons. Yet, the saint was saved by the purity of his soul.

The religious subject is presented in a revolutionary fashion; generations of earlier artists had tended to treat landscape as an unobtrusive backdrop of secondary importance, whereas now the landscape dominates the subject to such an extent that the temptation of Saint Anthony seems only incidental. This change of emphasis marks an important advance toward the development of pure landscape painting, in which Pieter Bruegel the Elder was an instrumental figure. Already, that delight in the natural world is apparent here in the shadowy depths of leafy forests, contrasting with open vistas of waterways, villages, and towns bathed in pearly light. Perhaps the juxtaposition of a peaceful landscape with the temptations and attacks of demons was a subtle statement by this Bruegel follower on the political and moral brutalities of his time. Possibly Saint Anthony is meant allegorically to represent Everyman caught up in a world gone mad.

Village Festival in Honour of Saint Hubert and Saint Anthony:

“The Kermesse of St George” and Festival in Honour of Saint Hubert and Saint Anthony: by Pieter Brugel is a subject of the theatrical scene in the centre of the composition is the rederijjker farce Een Cluyte van Plaeyerwater. The spectators are watching the climax of the farce, when the gullible husband Werenbracht jumps from his hiding place to confront his unfaithful wife and her lover, the local priest. The protoype for this famous composition is now lost, but its popularity is attested to by the number of extant copies.Peeter Baltens, a painter in the circle of Pieter Bruegel, played an important role in the Antwerp artists’ guild. He was also a rederijker (rhetorician): a poet and an actor. A comic dramatic work is being performed on the makeshift stage in the middle of this kermis scene. The farce is about a man – hidden in a pedlar’s basket – who catches his wife cheating on him with a clergyman. See Reformers on Stage: Popular Drama and Religious Propaganda.

Both Pieter Bruegel the Elder and his son Pieter the Younger painted mass scenes of revelry. A Village Fair nominally illustrates a religious festival, a welcome respite from the monotonous toil of peasant existence. Effigies of Saints Anthony and Hubert are carried in a procession through the village, but for the most part the spectators’ attention has been diverted elsewhere – they gaze instead at an absurd play, ‘Trick Water Farce’, by a group of travelling actors. Acts of individual devotion are still evident – a man kneels at confessional, two men toll the church bell, and another politely doffs his hat as he gives directions to two travelling monks. For the most part, however, the villagers are content to dance and sing in a carousing mêlée. Pieter Bruegel the Elder was influenced by the work of Hieronymus Bosch (c1450-1516), and saw his audience as the common people, rather than his bourgeois patrons.

- Terra Pacis

Terra Pacis, as we shall see, employs the symbol of humanity living in the land of ‘Ignorance’. The first part of the journey consists of a stage called by the Greek Fathers Praktikos, this is the stage of self-study through the practical disciplines of prayer and work through which the seeker learns to master the physical and psychological machinery that constitute his lower or worldly self. Read here the Praktikos

The next stage is that of Theoretikos or contemplation; the mystic is able to see what is, he is liberated from worldly matters towards which he is now objective – indifferent even – and is able to work on specific difficulties in his personal path.

The final stage, Gnostikos, knowledge of what John of Apamea in the 5th century called ‘invisible realities’,refers to a realm that cannot be described in ordinary human language.Read more about Gnostikos

These stages, Praktikos, Theoretikos and Gnostikos constitute the three main themes that inform Bruegel’s paintings. Every image, whether a detail or in the broad plan, serves the search for the meaning of humanity within God’s universal plan.

Much of the text of Terra Pacis – all the part that describes the ‘Land of Ignorance’ – refers to the first stage of the spiritual journey, that of the seeker’s awakening to the reality of his or her situation and accurately identifying the nature and quality of each difficulty.

The grim absurdity of all human endeavour, which would be comic if it were not so tragic, is revealed for what it is.

The philosophical point from which Bruegel views the world is very much that of Niclaes: humanity’s error in looking to the material world to solve questions that only the higher world can answer.

But humanity in general is ignorant of the higher world, as Bruegel demonstrates in his Numbering at Bethlehem and Adoration of the Kings, and especially when he implies that access to it is nearby: within and through oneself. (‘The Kingdom of Heaven is within you’.)

The Numbering at Bethlehem: see here description

Adoration of the Kings:

This emphasis on the uniqueness of each figure, and Bruegel’s lack of interest in depicting ideal beauty in the Italian manner, makes it clear that although borrowing an Italian compositional scheme, Bruegel is putting it to quite a different use. In this treatment, the painter’s first purpose is to record the range and intensity of individual reactions to the sacred event.

This emphasis on the uniqueness of each figure, and Bruegel’s lack of interest in depicting ideal beauty in the Italian manner, makes it clear that although borrowing an Italian compositional scheme, Bruegel is putting it to quite a different use. In this treatment, the painter’s first purpose is to record the range and intensity of individual reactions to the sacred event.

Humanity compounds this error by accepting, in the place of the higher life, a substitute; people allow themselves to be satisfied with the external formalities of pseudo-religion. ‘Their Religions or godservice is called the Pleasure of Men. Their doctrine and ministration is called Good Thinking’.

The text of Terra Pacis, like the anecdotes in Bruegel’s paintings, has higher significance only when considered from an esoteric point of view. Mystical literature has little meaning outside the psychological or spiritual realm. Every description is an account of subtle mental events and emotional currents whose energies, vibrating at varying tempos, animate our psycho-physical world. Our comprehension of what passes in our inner world depends on the quality and on the level of our consciousness; and consciousness, in its turn, depends on our ability to focus and hold a disciplined interior attention upon ourselves.

This will be clear to anyone who has experimented with meditation. The same would be true from the contemplative prayer traditions of Christianity such as were once readily available, as we see in the Philokalia anthology, to those who sought them and which today are difficult to find.

The Jesus Prayer is a short, formulaic prayer esteemed and advocated within the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches. It is, for the Orthodox, one of the most profound and mystical prayers and is often repeated endlessly as part of a personal ascetic practice. In a modern context the continuing repetition is regarded by some as a form of meditation, the prayer functioning as a kind of mantra. Anyway, it is not a mantra or magic formula, but a prayer.

Here, it may help to remind ourselves of the point already made that, in such work, the seeker studies the waywardness of the undisciplined and untrained mind as well as the unwillingness of the body to submit itself to stillness and silence. These are attributes of the confused and unredeemed world that is the human race’s inheritance from Adam, the ‘Old Man’.

But if he persists he will discover intimations of another life within himself waiting to be awoken: the ‘Buddha nature’, the ‘Christ within’ or the ‘New Man’. The nomenclature varies in the different cultures and civilizations that have existed but the essential truth that they describe is the same.

Thus when Niclaes exhorts his readers to ‘fly now out of the North and all Wildernessed Lands; rest not yourselves among the strange people, nor among any of the enemies of the House and Service of Love; but assemble you with us, into the Holy City of Peace, the New Jerusalem, which is descended from heaven and prepared by God’, the ideas of the Perennial Philosophy would insist that we follow with our psychological understanding, because Niclaes is describing psychological events and places within ourselves. The author is telling us to make an inner movement, to mobilize an inner attention, by whose action we can withdraw from the myriad thoughts and feelings that occupy our subconscious; we may then find the ordered place in ourselves where we can be open to a higher influence beneficial to our search for eternal values.

The language of Terra Pacis may sound quaint sometimes and the syntax is occasionally a little obscure. But, honouring the fact that this is the period of English literature that produced the Authorised Version and the Book of Common Prayer, the present writer has not sought to modernize the passages he has chosen. But we should not let the writing’s archaic cadences obscure the fact that H. N. speaks with spiritual authority and psychological accuracy about the human condition. Terra Pacis is a forgotten work, virtually unknown since the end of the 17th century. For that reason, as well as its considerable literary merit, more than half of the original text is reproduced in the Appendix.

The principle according to which psychological or spiritual transformation can take place is self-knowledge, the study of one’s inner world, called by writers of the mystical tradition ‘watching over oneself’ or ‘guarding the heart’.

The mystical seeker is a ‘traveler’ visiting and observing in himself all those aspects of thought, memory, imagination, feelings, inner attitudes, habits of mind and so on that make up the subconscious interior world that Niclaes describes as ‘wildernessed lands and ignorant people’.

We have gone through and passed beyond many and sundry manner of wildernessed lands and ignorant people and so have considered the nature of every land and people. Into all which we found the strange ignorant people very unpeaceable and divided in many kinds of manners, dispositions and natures, as also vexed with many unprofitable things to a great disquietness and much misery unto them all.

The whilst we considered diligently hereon, so we found by experience that every people had their disposition and nature, according to the dispositions and nature of the land where they dwelt or where they were born.

Niclaes, a master in the school of self-knowledge, is telling us of the subconscious world (the people are ‘ignorant’ due to the absence of conscious awareness) where attitudes and thoughts are subjective. It is this lack of objectivity that causes everything to be ‘unpeaceable and divided’.

Here H. N. touches on a central theme of the perennial tradition: man’s multiplicity ‘divided’, as he says, ‘in many kinds of manners, dispositions and natures’.

The situation for the interior state of unredeemed man is chaos, disorder and contradiction; the opposite of the condition of the heavenly city: ‘Jerusalem is a city built at unity within itself’. Psalm 122. v. 3.

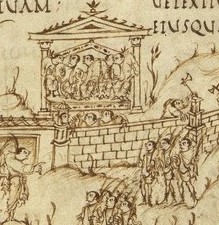

Note: PSALM 122 1 A gradual canticle. I rejoiced at the things that were said to me: We shall go into the house of the Lord . 2 Our feet were standing in thy courts, O Jerusalem. 3 Jerusalem, which is built as a city, which is compact together . 4 For thither did the tribes go up, the tribes of the Lord: the testimony of Israel, to praise the name of the Lord . 5 Because their seats have sat in judgment , seats upon the house of David. 6 Pray ye for the things that are for the peace of Jerusalem: and abundance for them that love thee. 7 Let peace be in thy strength: and abundance in thy towers. 8 For the sake of my brethren, and of my neighbours, I spoke peace of thee. 9 Because of the house of the Lord our God, I have sought good things for thee. Utrecht Psalter

An angel with a bannered staff flying down from heaven is addressing the psalmist and a group of people to the left who stand beside ‘the house of the Lord’ (verse 1), represented as a tabernacle with drawn curtains revealing a hanging lamp, and a draped altar.

To the right of the psalmist are they who are seated on the ‘thrones of judgment’ (verse 5).

The walls of ‘Jerusalem’ which is being ‘builded as a city’ stretch across the picture (verse 3).

In front of the gates, two men with palms are addressing three groups of the ‘tribes of the Lord’ (verse 4) on either side, who are going up to testify and give thanks unto the Lord. They all carry palms, as does also the psalmist.

Terra Pacis conclusion:

The outline of the spiritual predicament for humanity in all its grandeur and complexity becomes apparent. The solution to the difficulties of the situation is by the esoteric path, little known and difficult to find.

It is true that the whole earth is unmeasurable, great and large, and the lands and people are many and divers, but the most part of the lands are beset by grievous labor, and with much trouble the people are captivated with sundry unprofitable vexations.

But the children of the kingdom have a land that is void of all molestation and a City which is very peaceable. Verily, without this one City of Peace or Land of the Living there is no convenient place of Rest on the whole earth.

But this land of peace (which with his people is ful of joy and liveth in concord) is a secret land and is severed from all other lands and people. It is also known to no man but of his inhabitants. But the entrance into the same is very straight and narrow, for that cause it is found of few, but there are many that run past it or have not any right regard thereon. Therefore remaineth this good land of the living unloved and unknown of the most part of the strange people.

The founder of the Family of Love, offering himself as a guide, warns of the difficulties that beset the spiritual traveler and tells him that all will be well, provided that he himself wishes to make the journey.

We will show forth the neerest ways and the needfullest means and guides that lead thereunto, because that every traveller may keep the right High Way and keep the more diligent watch until he comes through the gate.

Seeing now that this way to the Holy Land is perilous to pass through, for him that is unexpert therein, so have we thought good to testifie and show forth distinctly (and that altogether to the preservation of the traveller) the most part of the wildernessed places of the strange people, and the perils of deceit, each one according to his pernicious disposition and nature; to the end that everyone may be of good cheer and may, without fear, pass through the way rightly and without harm, and that no man should remain lost, except he would himself.

The main part of the text of Terra Pacis can be read in;appendix terra pacis

this writer has added commentary where it may be helpful in bring the reader’s attention to Niclaes’ ideas relating to the teaching of the Perennial Philosophy and Peter Bruegel’s paintings. Of particular importance are passages with the themes of the ‘bread of life’, i.e. spiritual nourishment, employing the images of ‘corn’ and ‘seed’.

Later, a description of arms, armour and instruments of war corresponds to imagery in Bruegel’s Adoration of the Kings in the London National Gallery. Elsewhere there are lists of names indicating the behaviour of different types of people that could describe the characters in Bruegel’s ‘crowd scenes’ as seen in The Numbering at Bethlehem (1566) in Brussels and The Road to Calvary (1564) in Vienna. In another passage the text gives names for a group of suffering people that could be Jesus’ mother and her entourage in The Road to Calvary.

- Brueghel and Sufism

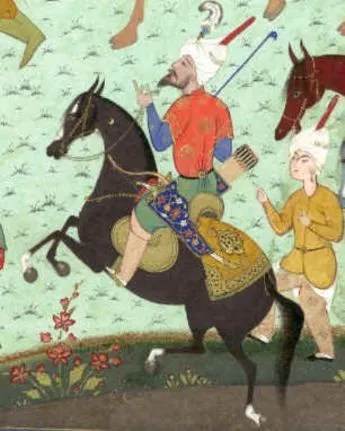

From the fact that Bruegel entered the Antwerp painters’ guild in 1551, it is inferred that he was born between 1525 and 1530 His master, according to Van Mander, was the Antwerp painter Pieter Coecke van Aelst.[

Between 1545 and 1550 he was a pupil of Pieter Coecke, who died on 6 December 1550.] However, before this, Bruegel was already working in Mechelen, where he is documented between September 1550 and October 1551 assisting Peeter Baltens on an altarpiece (now lost), painting the wings in grisaille.[Bruegel possibly got this work via the connections of Mayken Verhulst, the wife of Pieter Coecke. Mayken’s father and eight siblings were all artists or married an artist, and lived in Mechelen.

From 1555 until 1563, Bruegel lived in Antwerp, then the publishing centre of northern Europe, mainly working as a designer of over forty prints for Cock, though his dated paintings begin in 1557. With one exception, Bruegel did not work the plates himself, but produced a drawing which Cock’s specialists worked from. He moved in the lively humanist circles of the city, and his change of name (or at least its spelling) in 1559 can be seen as an attempt to Latinize it; at the same time he changed the script he signed in from the Gothic blackletter to Roman capitals.

In 1563, he married Pieter Coecke van Aelst’s daughter Mayken Coecke in Brussels, where he lived for the remainder of his short life. While Antwerp was the capital of Netherlandish commerce as well as the art market, Brussels was the centre of government. Van Mander tells a story that his mother-in-law pushed for the move to distance him from his established servant girl mistress. By now painting had become his main activity, and his most famous works come from these years. His paintings were much sought after, with patrons including wealthy Flemish collectors and Cardinal Granvelle, in effect the Habsburg chief minister, who was based in Mechelen. Bruegel had two sons, both well known as painters, and a daughter about whom nothing is known. These were Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564–1638) and Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625); he died too early to train either of them. He died in Brussels on 9 September 1569 and was buried in the Kapellekerk.[

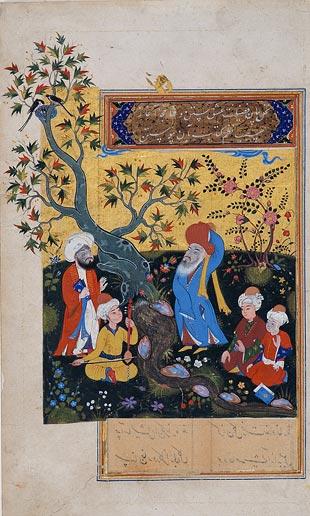

- Pieter coecke van Aelst in Istanbul

Pieter Coecke van Aelst or Pieter Coecke van Aelst the Elder (Aalst, 14 August 1502 – Brussels, 6 December 1550) was a Flemish painter, sculptor, architect, author and designer of woodcuts, goldsmith’s work, stained glass and tapestries.[1] His principal subjects were Christian religious themes. He worked in Antwerp and Brussels and was appointed court painter to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

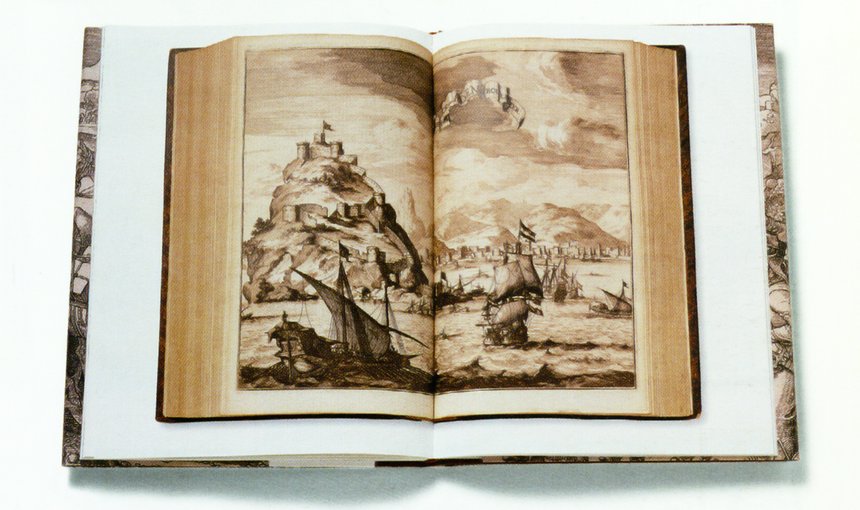

See here complete book Grand design

Coecke van Aelst was a polyglot. He published translations into Flemish (Dutch), French and German of Ancient Roman and modern Italian architectural treatises. These publications played a pivotal role in the dissemination of Renaissance ideas in Northern Europe. They contributed to the transition in Northern Europe from the late Gothic style then prevalent towards a modern ‘antique-oriented’ architecture.

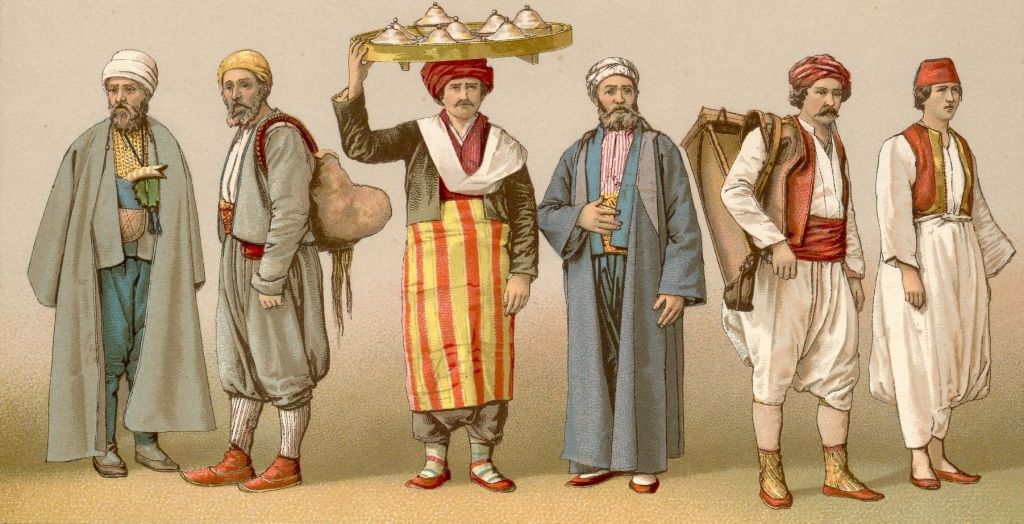

Coecke van Aelst is recorded joining the local Guild of Saint Luke of Antwerp in 1527. In 1533, he travelled to Constantinople where he stayed for one year during which he tried to convince the Turkish sultan to give him commissions for tapestries. This mission failed to generate any commissions from the sultan. Coecke made many drawings during his stay in Turkey including of the buildings, people and the indigenous flora. He seems to have retained from this trip an abiding interest in the accurate rendering of nature that gave his tapestries an added dimension. The drawings which Coecke van Aelst made during his stay in Turkey were posthumously published by his widow under the title Ces moeurs et fachons de faire de Turcz avecq les regions y appertenantes ont este au vif contrefaictez (Antwerp, 1553).

The diplomatic mission left Vienna in April 1533. They sailed from Rijeka and, after crossing Bosnia, Serbia and Bulgaria, they reached Istanbul in May 1533. Coecke stayed in Istanbul until July of that same year. After his return, in 1534, he was named official painter to Charles V. In 1539 he translated S. Serlios’ treatise on architecture and perspective from Latin to Flemish, and later on Vitruvius’ work on architecture. Coecke was also in charge of the decoration of several public buildings, and became famous for his wood engravings. Those engravings are remarkable for their rich detail and their particular strain of humour. His tapestry workshop was very productive, and Coecke himself was the designer of several masterpieces of the art of tapestry. On the other hand, few of his paintings survive, as many were destroyed during the iconoclastic riots of the 16th century (Beeldenstorm). His work forms part of the Romanic school of Antwerp, in which Flemish art shows the marked influence of Raphael.

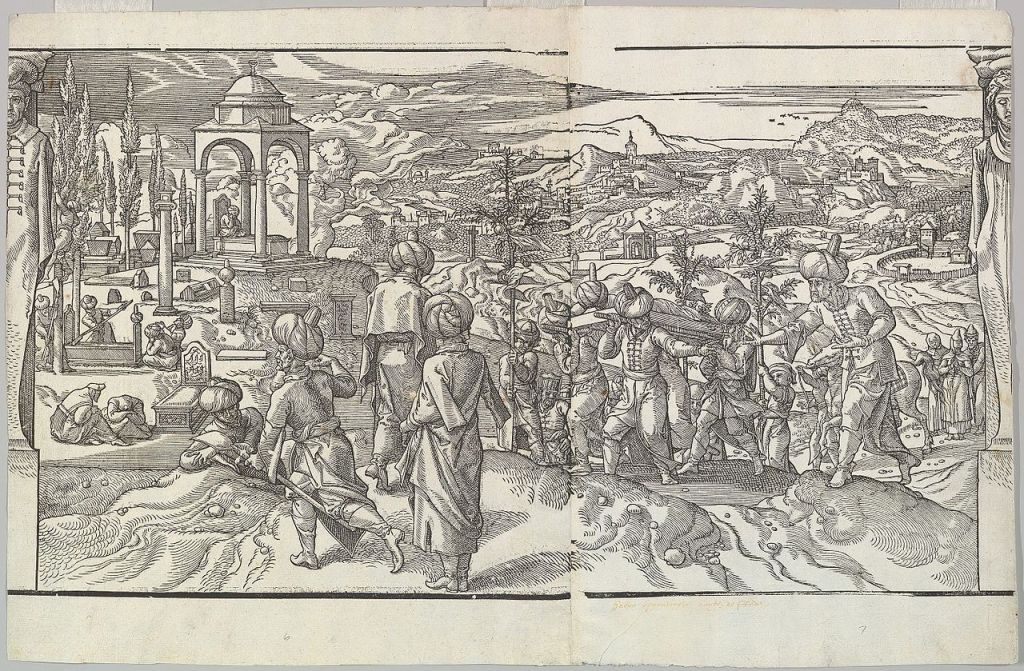

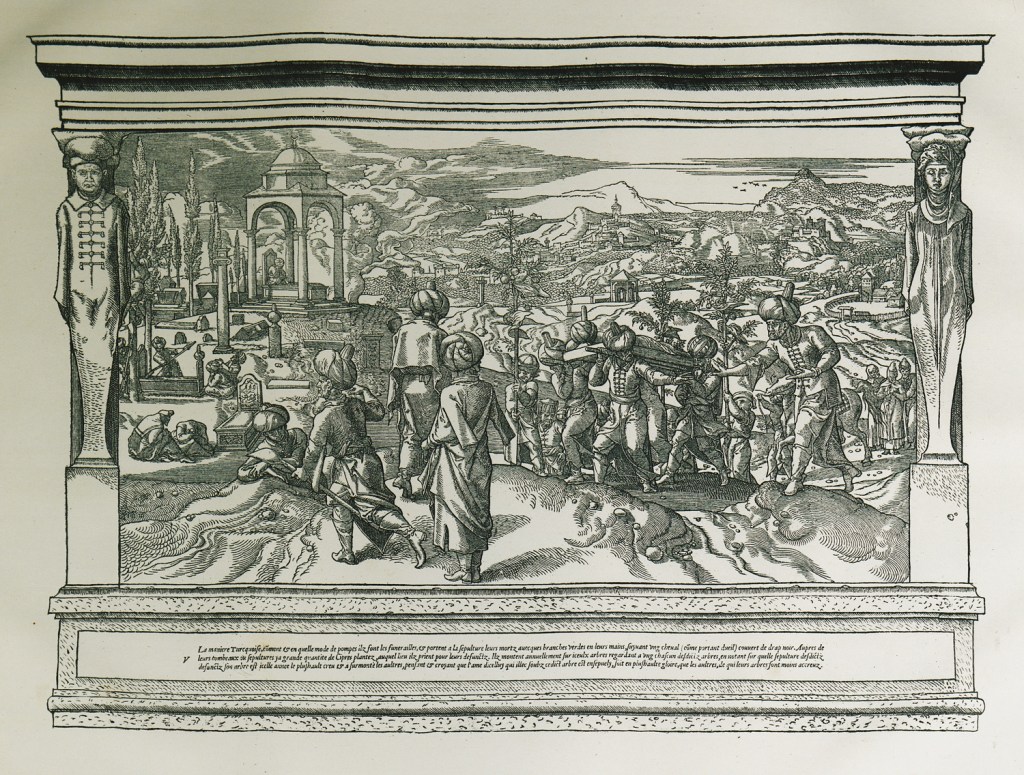

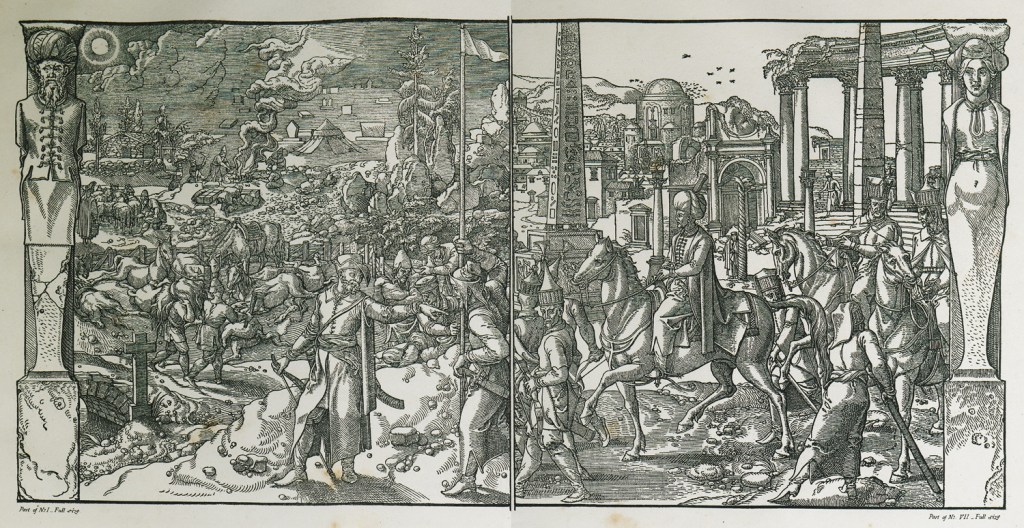

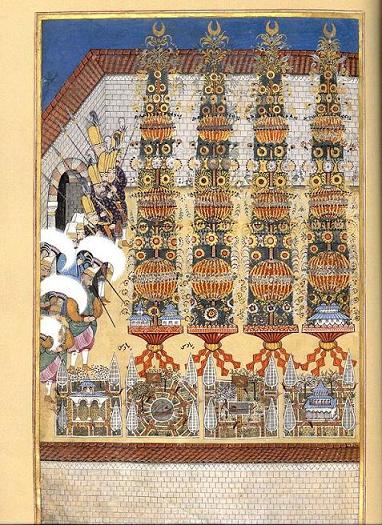

After Coecke’s death, his widow published this series of seven engravings, pasted on a five-meter long canvas, and separated by Caryatid figures. These extremely rare engravings are groundbreaking and unique, both for their subjects and for their technique. They depict moments of the mission’s journey to Istanbul, including the encampment at modern-day Serbia, the crossing of Hebrus river, other stops of the caravan, everyday activities of the locals, the celebration of the full moon at the outskirts of Plovdiv (Philippopolis), a funeral near Edirne (Adrianople), feasts at the Golden Horn, and the procession which escorted the Sultan as he rode from the Palace to the Byzantine Hippodrome. Coecke is discreetly depicted in each one of his engravings.

Barring the drawings and paintings of Gentile Bellini, the Italian painter who visited at Mehmed’s court in 1480, there are no depictions of Ottoman rulers before Coecke’s drawings. Suleiman I became an admirer of Coeckes’ work, consented that he paint his portrait and lavished him with expensive gifts.

Map of Istanbul, showing some of the city’s main sights: A. The Plataean Tripod at the Byzantine Hippodrome B. The Column of Arcadius C. The Patriarchate of Constantinople D. The church of Hagioi Apostoloi, Istanbul. E. Atik Mustafa Pasa Mosque at the area of Vlacherna, initially a church built in the Byzantine era; its original dedication remains unknown. F. Cannons used in Suleiman I’s campaigns to Belgrade, Rhodes and Budapest.

Coecke’s spectacular Customs and Fashions of the Turks (Moeurs et fachons de

fair de Turcz) is unique in the history of printmaking. The woodcut, composed of seven scenes

printed from ten carved woodblocks, measures about fifteen feet in length.The frieze evokes in

pictures the people, customs, and landscape of the Ottoman Empire that Coecke witnessed on the journey he took to Constantinople (now Istanbul) in 1533. The print was not issued by his wife, Mayken Verhulst, until 1553, twenty years later and three years after the artist’s death. It was based on Coecke’s designs drawn after his return and intended most likely for an unrealized tapestry series.

The naturalistic rendering of the traditions and habits of foreign cultures set before panoramic

landscapes and city views in frieze form was unprecedented in Netherlandish art at the time.

The title page of the print reveals the source of Coecke’s imagery: it states that the

scenes were “au vif contrefaictez par Pierre Coeck d’Alost, luy estant en Turquie, l’An de Iesuschrist M.D. 33” (drawn from life by Pierre Coeck d’Alost, when he was in Turkey, the year of our lord M.D. 33). Karel van Mander described Coecke’s voyage in his biography of the artist, published in 1604:

He was urged on by some tradesmen, tapestry-makers from Brussels called Van der Moeyen, to travel to Constantinople in Turkey where they were planning to undertake something special by making beautiful, costly tapestries for the Great Turk, and they got Pieter to paint some things for that purpose to show the Turkish Emperor; but since the Turk, according to his Mohammedan Law, did not want figures of people or animals, it was fruitless and nothing came of it — except that a useless journey and high expenses incurred. Pieter, who was there for about a year, learned the Turkish language, and, as he could not be idle, he meanwhile, for his own pleasure, drew the city of Constantinople from life with many neighboring locations; these things are published in woodcut print.

The accuracy of the specific details in Van Mander’s account may be questionable, but archival

sources provide evidence for the trip.The Augsburg merchant Jacob Rehlinger and the Antwerp

merchant of luxury goods Pieter van der Walle signed a contract, still extant, with the Brussels

tapestry maker Willem Dermoyen on June 15, 1533. In the contract, the two merchants arranged with the tapestry maker for an option to create new editions of Bernard van Orley’s Hunts of Maximilian and Battle of Pavia, and they received samples of each series to send abroad. Read more here

The iconographic programme cannot be grasped without an indepth understanding of