From: the metaphysical symbolism of the Chinese tortoise

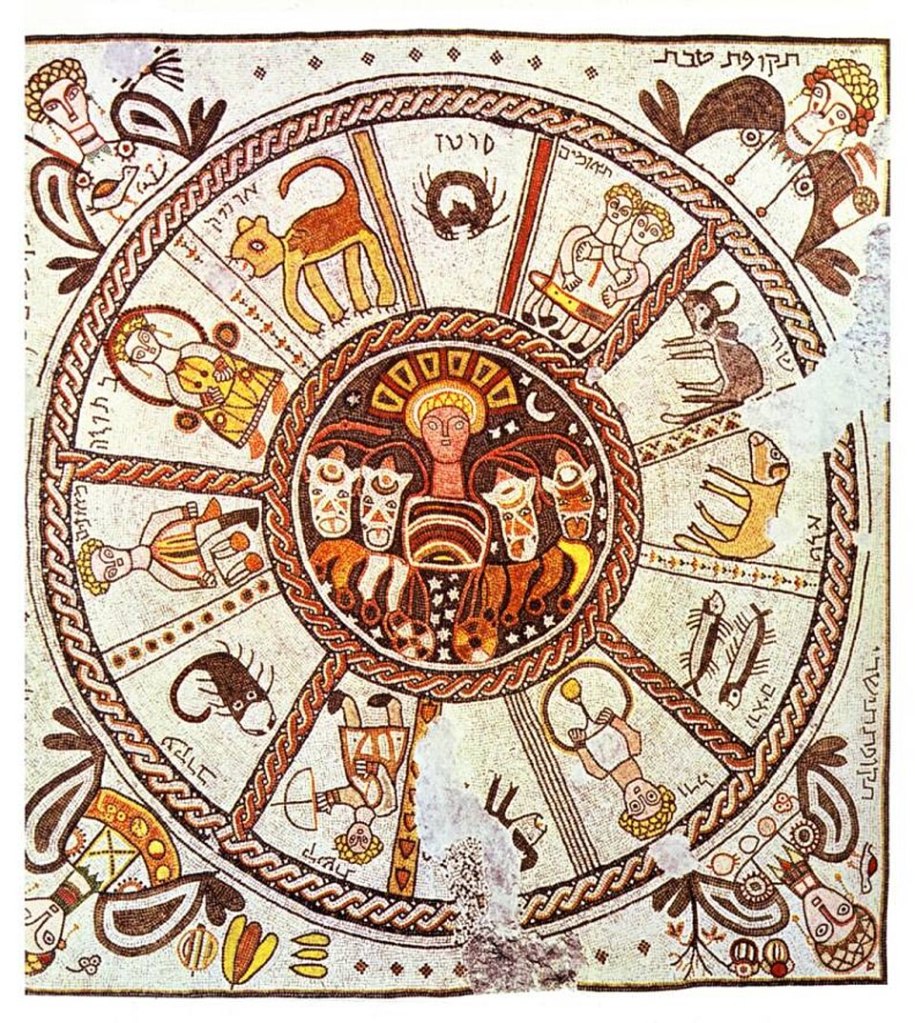

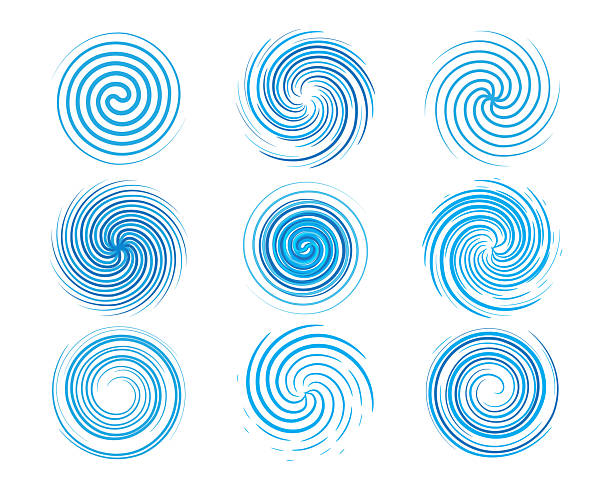

There are two separate versions of the myth of Nüwa which describe the origin of chaos in the world. (In Chinese, the word for ‘whirlpool’ is wo (渦), which shares the same pronunciation with the word for ‘snail’ (蝸). These characters all have their right side constructed by the word wa (咼), which can be translated as ‘spiral’ or ‘helix’ as noun, and as ‘spin’ or ‘rotate’ when as verb, to describe the ‘helical movement’. This mythical meaning has also been symbolically pictured as compasses in the hand which can be found on many paintings and portraits associated with her.)

The first myth is from Lun Heng and describes how Mount Buzhou was tilted during the battle between Gong Gong and Zhuan Xu for the lordship. However, the battle damaged Mount Buzhou, one of the sky pillars, and the sky’s ties with the earth were severed. This caused the sky to incline to the northwest and, as a result, astral bodies move in a westerly direction, while the rivers of China flow towards the ocean (in the east). In the Huainanzi version, the world was engulfed in a catastrophic deluge and was saved by Nüwa who mended the sky with five magical stones. Both versions include Nüwa cutting of the legs of a tortoise to hold up the sky and repairing the sky with five magical stones. The following text is from the Huainanzi:

“The four pillars were broken; the nine provinces were in tatters. Heaven did not completely cover [the earth]; Earth did not hold up [heaven] all the way [its circumference]. Fire blazed out of control and could not be extinguished; water flooded in great expanses and would not recede… Nüwa smelted together five-colored stones1 in order to patch up the azure sky, cut off the legs of the great tortoise to set them up as the four pillars…”

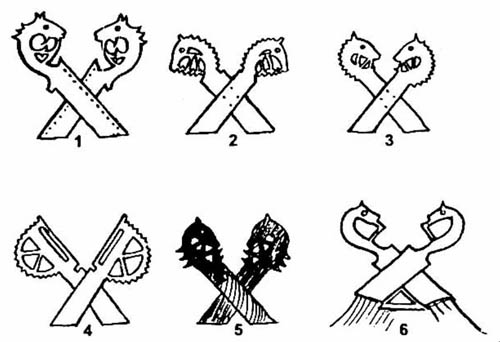

The myth follows a general explanatory pattern. The first example is the four pillars that hold up the sky and fall into a state of disrepair. These four pillars belong to a cosmological belief found across different cultures: that heaven is supported by pillars or on some kind of foundation. According this myth, the pillars are in the form of mountains. The second example is the existence of fire and water in this myth before anything else, which infers the intermingling of Yin and Yang before the introduction of order from the chaos and the separation of heaven and earth. Furthermore, the ‘five colored stones’ actually represent the five elements created by Nüwa to repair the sky (heaven) and replace the broken pillars with the legs of a tortoise. Although the myth contains no images that explicitly illustrate the tortoise supporting the earth like in other cultures, (he world tortoise in Hindu culture holds up four elephants and in turn they supported the world above; Next, the myth “Churning of the milky ocean” depicts Vishnu incarnated as a tortoise as the base supporting the pillar where the asura and devas were wrestling to churn the milk ocean.) we can assume that the tortoise, or at least part of it, does actually support the sky.

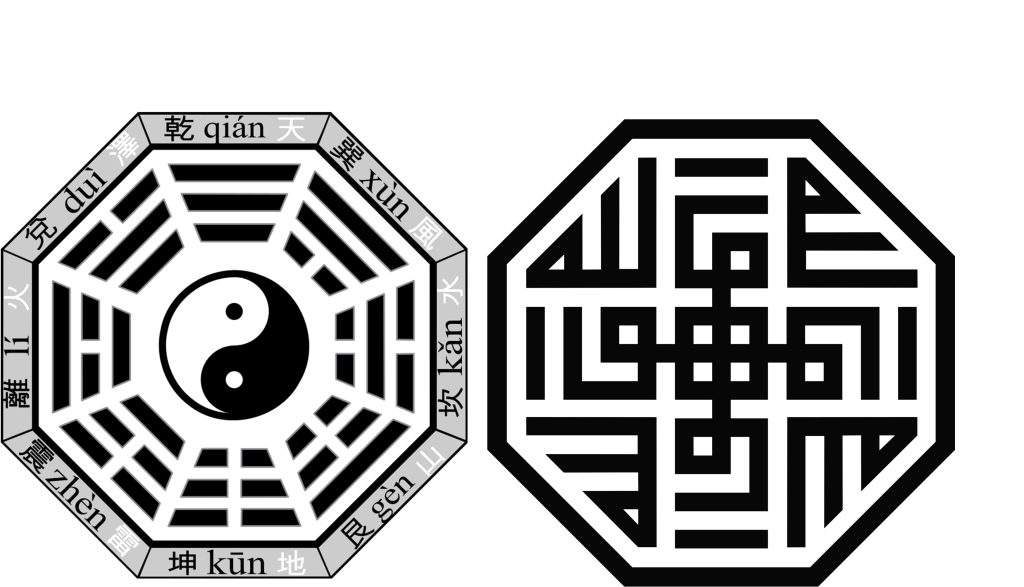

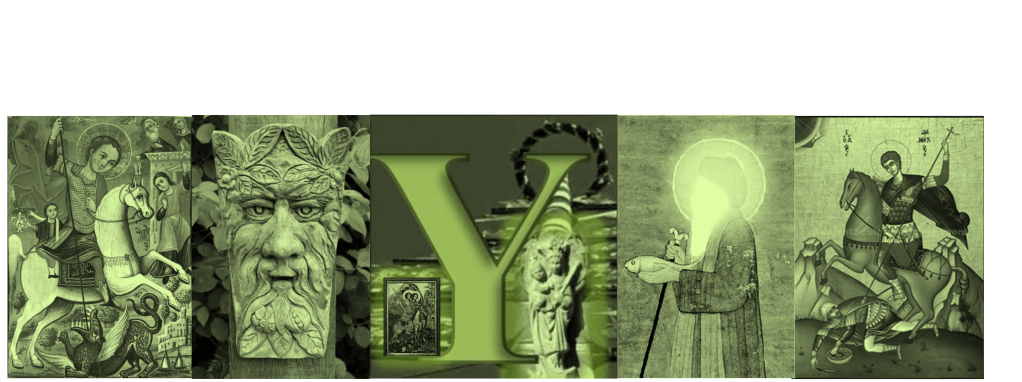

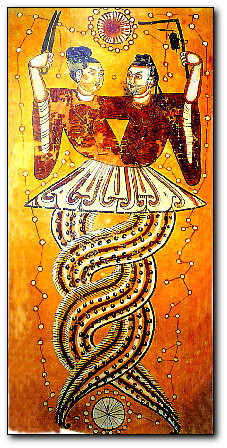

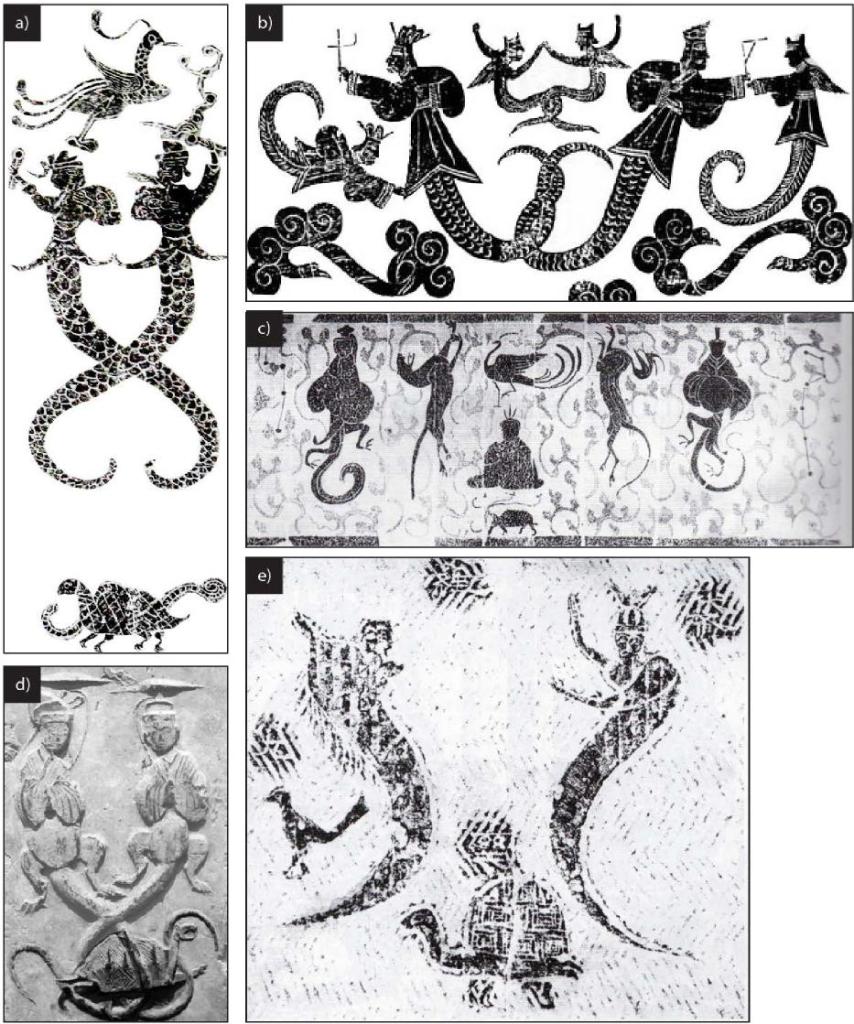

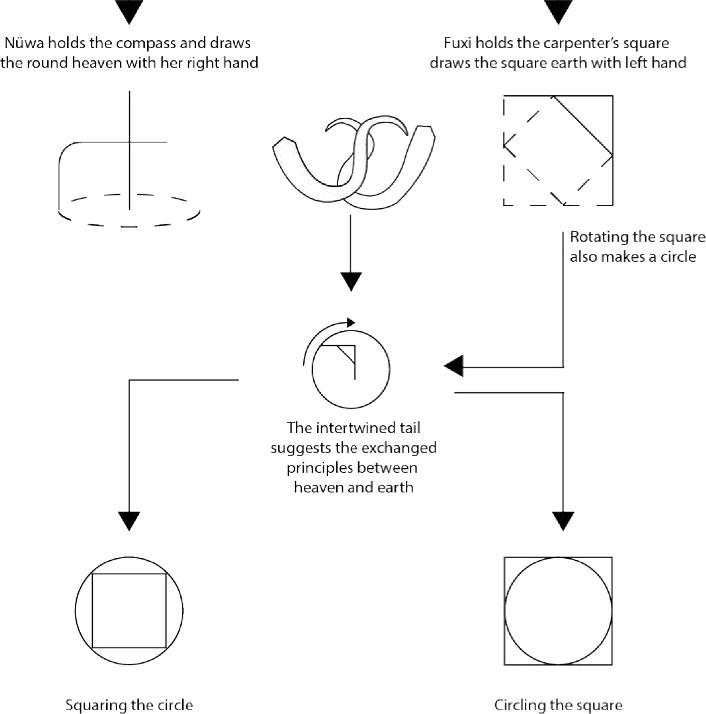

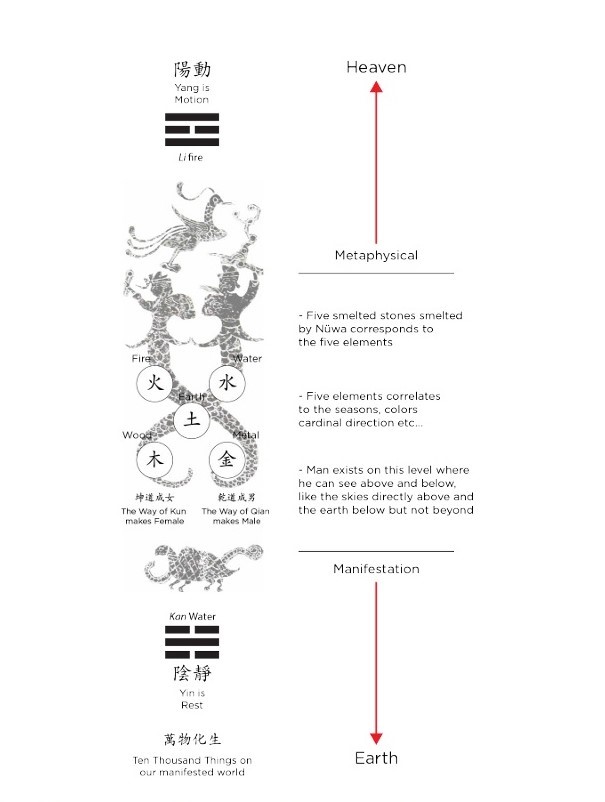

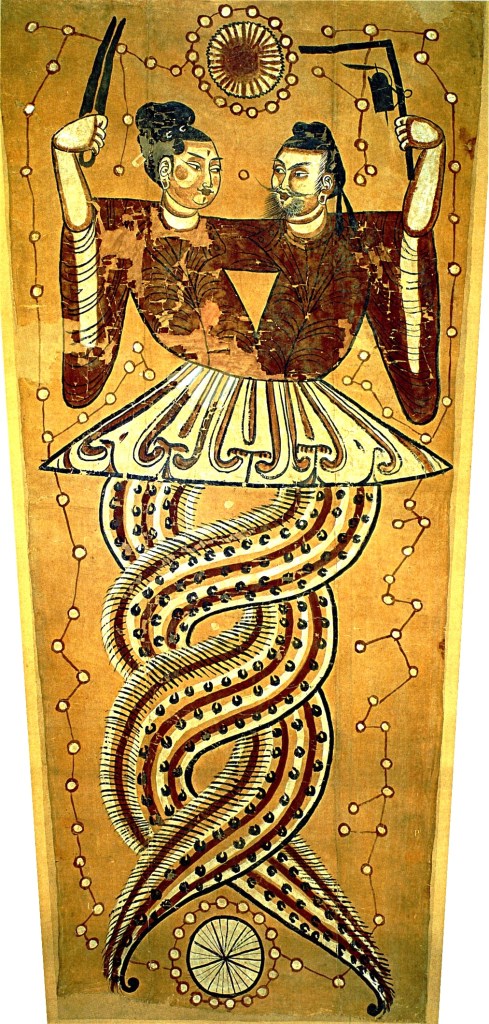

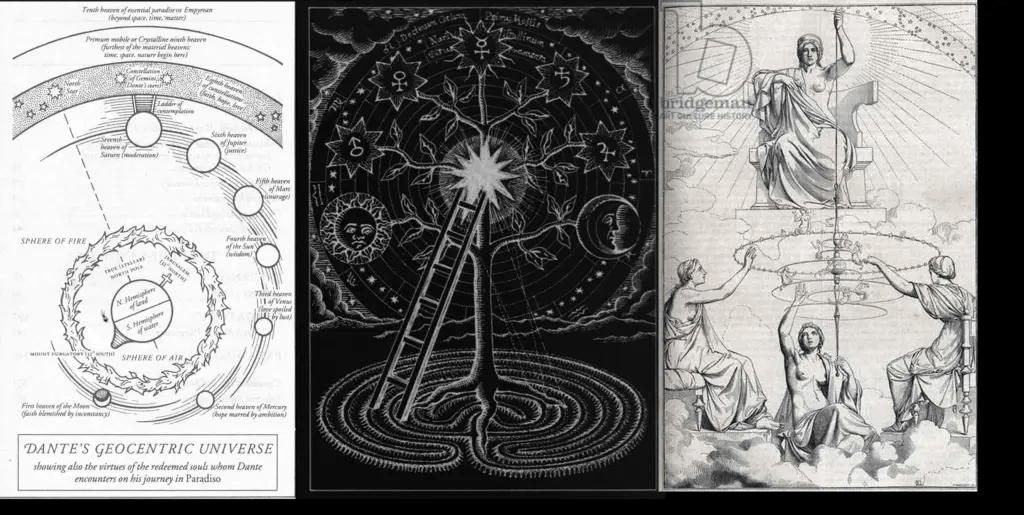

Images of Nüwa usually depict with a partner figure, Fuxi. In many rubbings and images, they are depicted with human upper bodies with serpentine tails If their tails are entwined, it symbolizes the interaction of Yin and Yang, depicting male and female aspects co-existing as complementary pairs rather than polarities. Similar intertwinement can be observed in images of the tortoise and the snake. Nüwa and Fuxi5 appear together holding a compass (gui) and a square respectively (ju). Together, they represent stability and order, and this was exactly what the pair introduced into the world when it was engulfed in turmoil and unrest. Fuxi was known as the sage that taught mankind how to hunt and cook, and, together with Nüwa, he established the four seasons. The introduction of order and harmony in the world was achieved by the use of two special tools, the compass and the square. Nüwa holds the compass while Fuxi holds the square; the tools are correlated with the circular heaven and the square (or rectilinear) figures of Earth and Heaven respectively . Guénon suggests that the opposition of the square and circle suggests a passage from the human state, represented by the earth and can be directly perceived by man, to the supra-human states, represented by heaven. In other words, the tools represent a passage from the domain of the ‘lesser mysteries’ to that of the ‘greater mysteries.’

The compass, being a ‘celestial’ symbol,represents the Yang and the masculine, and therefore should belong to Fuxi (Yang principle) as the symbol of Heaven is circular or spherical. The square, being a ‘terrestrial’ symbol, represents the Yin and the feminine, and therefore should belong to Nüwa (Yin principle).This does not seem to be the case, it is Fuxi who holds the square (Fuxi being male and correlate to yang principle, which is symbolized by Heaven and circle shape) and Nüwa who holds the compass (Nüwa being female and correlate to yin principle, which is symbolized by Earth and square shape). If we were to recall, within the symbol of the yinyang, there is a yin within the yang and the yang within the yin, this is symbolized by entwined serpentine tail. The images showing Nüwa holding the compass are a sign of the world’s stability as she repaired the heavens using it. While the compass is associated with the tangibility of manifestation, and the shape of the square represents the weight of stability. (The compass is used to draw the circle or the sphere. It is intrinsically the primordial form because it is the least ‘specified’ of all, similar to itself in every direction in such a way that in any rotatory movement about its center, all its successive positions are strictly superimposable one on another. Therefore the sphere is considered by Guénon to be the most universal form of all, containing in a certain sense all other forms which will eventually emerge from it by means of differentiations taking place in certain particular directions. Guénon, R. (2001). The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times: Sophia Perennis, p.137.)

The square, held by Fuxi, does indeed belong to him, being the ‘Lord of the Earth’, mentioned by Guénon, whom rules by the square.( The cube or square is opposed to the sphere as being the most ‘arrested’ form of all, and therefore related to the earth as the ‘terminating and final element’ of manifestation in the corporeal state. It is also called the ‘stopping point’ of the cyclical movement. Furthermore, it is in a sense above all that of the ‘solid’ and symbolizes stability as it gains equilibrium of a cube resting on one of its faces and is considered more stable than any other body. Ibid, 138.) He is no longer considered to be related to Nüwa as he is a manifestation of Yin-Yang after being reintegrated into the state of a ‘primordial man’. From this viewpoint, the symbol of the square takes on another meaning, and the two rectilinear arms demonstrate the two squares being joined to form a rectilinear form is interpreted by Guénon as a union of the horizontal and the vertical.134 The Zhou Bi, a mathematical classic attributed to the Duke of Zhou, analyzes the problem of fitting the square within the circle and vice versa.135

Each shape can fit within each other by using two methods. The first method involves ‘circling the square’, which makes a circle within a square, while ‘squaring the circle’ involves making a square within a circle.136 It is further explained in the Zhou Gnomon that rotating a square can make a circle and that joining two try squares can make a square. ‘The square pertains to Earth, and the circle pertains to Heaven. Heaven is circle, and Earth is square.’ This observation, together with the intertwined tails of Nüwa and Fuxi, further suggests that Fuxi, the ‘Primordial Man’, has the potential to assimilate both heaven and earth (Yin and Yang), transcending the ordinary man. By extension, this harmonious unity applies to the earth and heaven as well as Yin and Yang. ( The ‘Primordial Man’ is considered to have passed from the circumference to the center (Buddhism expresses this term anägamī, that is, ‘he who returns not’) to another state of manifestation. In other words, the ‘Primordial Man’ is no longer affected by his conditioned existence despite being in that current state. On the other hand, in the eyes of ordinary men, he is considered as an ‘agent’ or representative of Heaven, which through his actions and influence, is the ‘center’ and the conduit of the ‘activity of Heaven’ itself. Just like the Emperor, without ever leaving the Ming Tang, he controls all the regions of the Empire and regulates the course of the annual cycle, for ‘To be concentrated in non-action, that is the Way of Heaven’.)

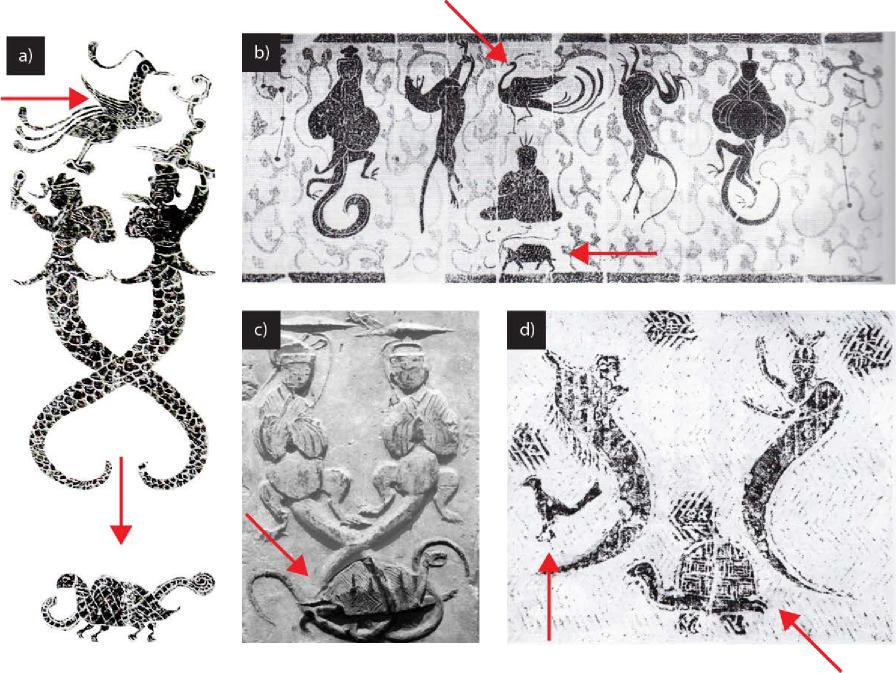

From the myth of Pangu and the tale of Nüwa and Fuxi, it can be inferred that the fire and water have a strong connection to the concept of Yin and Yang. In the various depictions of Fuxi and Nüwa, this view is indeed reinforced and in some images, we notice the presence of the tortoise at the bottom and a bird on the top . In all four images the tortoise is situated at the bottom; a plausible reason for this is its strong association with the earth and the Yin principle. Furthermore, anything above the tortoise shell is considered to be ‘Yang’ or heaven, because the shell symbolizes the round, domed shape of heaven. Hence, the tortoise ‘supports’ images that are above it in the realm of heaven.

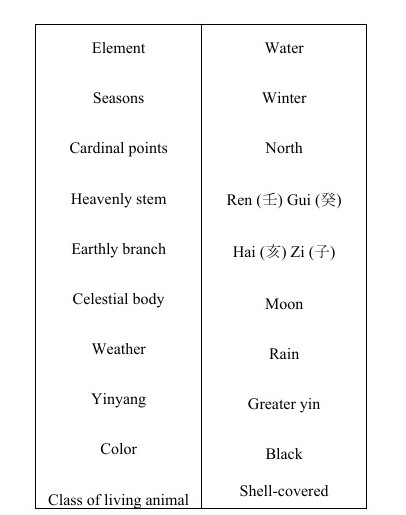

The myth of Nüwa and Fuxi supports this idea as the legs of the tortoise were cut and used to support the azure sky. It is also widely known that the black tortoise represents the Northern direction; therefore, from the table of correlations , the tortoise belongs to the category of “north” and all things associated with it. Also, what is ‘below’ the tortoise is actually earth and water. From the image, we can infer that where the tortoise is situated represents the northern sector. Directly opposite north is the south and therefore, the bird-like figure is identified as the vermillion bird of the south.

| Visual Analysis | ||

| Bird | Tortoise | Nuwa & Fuxi |

| Above | Below | Left & Right |

| Flying | Crawling | Middle |

| Light | Heavy | Balanced |

| Yang | Yin | Female/Male Principle |

| Near Heaven | Near Earth | Middle |

| Active | Passive | Circle & Square |

| Fire | Water | Moon & Sun |

The tortoise therefore assumes the role of an indicator of a larger context; it contains the whole Chinese cosmological view of Yin (earth) and Yang (heaven) symbolized by its plastron and shell respectively, aspects which we will examine more closely in the following chapter. The tortoise is also part of the visual language of our reference, indicating its principles are firmly rooted in the north and its associated aspects. As a macrocosm, the bird and the tortoise both function as indicators of fire and water, heaven and earth, Yang and Yin, as both animals are respectively light and heavy. Together with images of Fuxi and Nüwa, they symbolize the male and female principles under heaven (bird) and atop earth (tortoise). From Zhou Dunyi’s diagram, we can observe the relationships between heaven/earth, fire/water, and male/female.

along with other various principles.

In summary, we observe the tortoise’s legs replace the pillars supporting the Heaven, Nüwa using the five stones which parallels the five elements that was believed to be the fundamental building blocks that was believed to make up the world between Heaven and Earth. Fuxi and Nüwa instruments, the compass and the square are used to draw order from chaos through the symbol of square and circle that corresponds to Heaven and Earth. In a way, these repeated shapes could be found within the tortoise form – the round dome or circular depending on which view we look at it and the plastron of the tortoise, that corresponds to the four directions on the terrestrial as well as in the celestial sphere.

(a stylised 禄 lù and/or 子 zi character, meaning respectively “prosperity”, “furthering”, “welfare” and “son”, “offspring”. 字 zì, meaning “word” and “symbol”, is a cognate of 子 zi and represents a “son” enshrined under a “roof”. Lùxīng (禄星 “Star of Prosperity”) is Mizar (ζ Ursae Majoris) of the Big Dipper or Chariot constellation (within Ursa Major) which rotates around the north celestial pole; it is the second star of the “handle” of the Dipper. Zi was the name of the royal lineage of the Shang dynasty, and is itself a representation of the north celestial pole and its spinning stars (Didier, p. 191 and passim). Likewise to the Eurasian swastika symbols, representations of the supreme God manifesting as the north celestial pole and its Chariot (Assasi, passim; Didier, passim), the lu or zi symbol represents the ordering manifestation of the supreme God of Heaven (Tiān 天) of the Chinese tradition. Luxing is conceived as a member of two clusters of gods, the Sānxīng (三星 “Three Stars”) and the Jiǔhuángshén (九皇神 “Nine God-Kings”). The latter are the seven stars of the Big Dipper plus two less visible ones thwartwise the “handle”, and they are conceived as the ninefold manifestation of the supreme God of Heaven, which in this tradition is called Jiǔhuángdàdì (九皇大帝, “Great Deity of the Nine Kings”) (Cheu, p. 19), Xuántiān Shàngdì (玄天上帝 “Highest Deity of the Dark Heaven”) (DeBernardi, pp. 57–59), or Dòufù (斗父 “Father of the Chariot”). The number nine is for this reason associated with the yang masculine power of the dragon, and celebrated in the Double Ninth Festival and Nine God-Kings Festival (DeBernardi, pp. 57–59). The Big Dipper is the expansion of the supreme principle, governing waxing and life (yang), while the Little Dipper is its reabsorption, governing waning and death (yin) (Cheu, p. 19; DeBernardi, pp. 57–59). The mother of the Jiuhuangshen is Dǒumǔ (斗母 “Mother of the Chariot”), the female aspect of the supreme (Cheu, p. 19; DeBernardi, pp. 57–59). Source#1: Didier, John C. (2009). “In and Outside the Square: The Sky and the Power of Belief in Ancient China and the World, c. 4500 BC – AD 200”. Sino-Platonic Papers. Victor H. Mair (192). Volume II: Representations and Identities of High Powers in Neolithic and Bronze China Source #2: Assasi, Reza (2013). “Swastika: The Forgotten Constellation Representing the Chariot of Mithras”. Anthropological Notebooks (Supplement: Šprajc, Ivan; Pehani, Peter, eds. Ancient Cosmologies and Modern Prophets: Proceedings of the 20th Conference of the European Society for Astronomy in Culture). Ljubljana: Slovene Anthropological Society. XIX (2). ISSN 1408-032X. Source#3: Cheu, Hock Tong (1988). The Nine Emperor Gods: A Study of Chi Source#4: DeBernardi, Jean (2007). “Commodifying Blessings: Celebrating the Double-Yang Festival in Penang, Malaysia and Wudang Mountain, China”. In Kitiarsa, Pattana. Religious Commodifications in Asia: Marketing Gods. Routledge. Source #5: Ma Pilar Burillo-Cuadrado (2014). “The Swastika As Representation Of The Sun Of Helios And Mithras”. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 14, No 3, pp. 29-36 Source #6: A reconstruction of Zhū Xī’s religious philosophy inspired by Leibniz :the natural theology of heaven (2014).

Most challenging are the veils from Taoist-Buddhist tombs at Astana, in Central Asia, originally Nestorian (Christian) country, discovered by Sir Aurel Stein in 1925… We see the king and queen embracing at their wedding, the king holding the square on high, the queen a compass. As it is explained, the instruments are taking the measurements of the universe, at the founding of a new world and a new age. Above the couple’s head is the sun surrounded by twelve disks, meaning the circle of the year or the navel of the universe. Among the stars depicted, Stein and his assistant identified the Big Dipper alone as clearly discernable. As noted above, the garment draped over the coffin and the veil hung on the wall had the same marks; they were placed on the garment as reminders of personal commitment, while on the veil they represent man’s place in the cosmos. (pg. 111-12)…In the underground tomb of Fan Yen-Shih, d. A.D. 689, two painted silk veils show the First Ancestors of the Chinese, their entwined serpect bodies rotating around the invisible vertical axis mundi. Fu Hsi holds the set-square and plumb bob … as he rules the four-cornered earth, while his sister-wife Nü-wa holds the compass pointing up, as she rules the circling heavens. The phrase kuci chü is used by modern Chinese to signify “the way things should be, the moral standard”; it literally means the compass and the square.

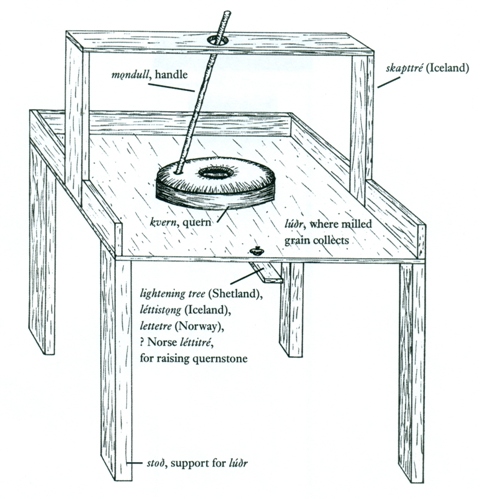

- The Millstone in Mythology: A Symbol of Cosmic Order, Justice, and Transformation

In the mythologies of diverse cultures, the millstone appears not merely as a tool of agrarian labor but as a symbol imbued with immense metaphysical weight. Whether functioning as a source of abundance, an agent of justice, or a mechanism of fate, the millstone represents the cyclical and transformative forces that underpin both the human and the cosmic condition. From Norse sagas to African oral traditions and biblical parables, this humble object becomes a metaphor for the profound **interplay between creation, destruction, and moral consequence.

*Grotti’s Mill: Cosmic Power and the Consequences of Exploitation

One of the most striking mythological representations of the millstone occurs in Norse mythology with the tale of Grotti’s Mill, found in the Grottasöngr. This enchanted mill is capable of grinding anything the owner desires—peace, gold, or destruction. When King Frodi acquires the mill and forces two giantesses, Fenja and Menja, to labor ceaselessly, their grinding shifts from prosperity to vengeance. Ultimately, they bring about Frodi’s ruin by unleashing chaos through the mill.

Here, the millstone symbolizes the fragile balance of cosmic order. When treated with respect, it generates peace and wealth; when abused, it yields destruction. The myth functions as a cautionary tale about hubris, greed, and the exploitation of natural or divine forces, reflecting an early understanding of what we might now call ecological or spiritual backlash.

The Sampo: Mythical Mill of Prosperity in the Kalevala

A parallel motif exists in Finnish mythology in the form of the Sampo, a magical artifact described in the *Kalevala*, Finland’s national epic. Often interpreted as a millstone or cosmic mill, the Sampo endlessly produces grain, salt, and gold. Forged by the smith Ilmarinen, it is later stolen and lost at sea, bringing misfortune to the land and its people.

The Sampo, like Grotti’s Mill, symbolizes the source of life and abundance, but also its fragility. Its disappearance suggests that prosperity is not a permanent condition—it must be protected, cultivated, and used wisely. The Sampo functions mythologically as a cosmic center, a generative force whose disruption signals the dissolution of harmony.

Biblical Imagery: Judgment and the Weight of Moral Responsibility

In Christian scripture, the millstone takes on a different, though equally profound, symbolism. In the Gospel of Matthew (18:6), Jesus states,*”If anyone causes one of these little ones…to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea. Here, the millstone is a metaphor for divine justice—an inescapable consequence for those who harm the innocent.

The weight and permanence of a millstone suggest the inescapable burden of guilt and the absolute nature of moral law. Unlike the Norse and Finnish mills, which produce external conditions (peace, gold, war), the biblical millstone is internalized—a representation of conscience, consequence, and ultimate accountability.

The Millstone in African and Ancient Mesopotamian Cosmologies

In West African oral traditions, the act of grinding grain—often done by women—carries sacred meaning. The millstone becomes a symbol of female power, ancestral continuity and **transformation**. It is both a domestic object and a spiritual one, representing the conversion of raw nature into nourishing culture. Similar motifs appear in Mesopotamian religion, where goddesses like Nisaba, associated with grain and wisdom, were linked to the act of milling as a divine function.

These traditions emphasize the millstone as a transformative force—a symbol not only of sustenance but of cultural identity, spiritual labor, and the cyclical regeneration of life through the feminine.

Universal Themes: Turning Wheels and Eternal Cycles

Across all these myths, the millstone serves as more than an instrument—it is a rotating axis, evoking imagery of the wheel of time, the cycle of karma, or the eternal return. The turning motion of the mill mirrors the revolutions of the stars, the seasons, and the soul’s journey through time. Whether used to produce food, treasure, or doom, the millstone becomes an agent of cosmic repetition and renewal.

Conclusion: The Millstone as a Symbolic Nexus*

The recurrence of the millstone across global mythologies suggests its function as a symbolic nexus—a point where material labor, metaphysical power, and moral consequence converge. It represents the processes that **grind down, refine, and reveal**: grain into flour, effort into sustenance, action into destiny. Whether in the hands of gods, giants, or mortals, the millstone reflects a core philosophical truth: that all creation involves a turning, a grinding, a cost—and ultimately, a transformation.

- Spinning Symbolism in Mythology:

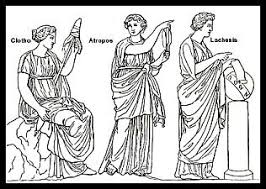

Clotho, Lachesis, Atropos: The three Moirai (Fates) spin, measure, and cut the thread of life.

Clotho spins the thread (beginning of life). Lachesis measures its length (the life span). Atropos cuts it (death).

Symbolism: Spinning here represents the control over life’s journey — creation, destiny, and inevitable fate.

Spider Goddess Neith (Egyptian Mythology) Neith is a primordial deity associated with weaving the world into existence. Sometimes depicted as weaving reality itself. Symbolism: The act of spinning/weaving equates to cosmic creation — crafting order from chaos.

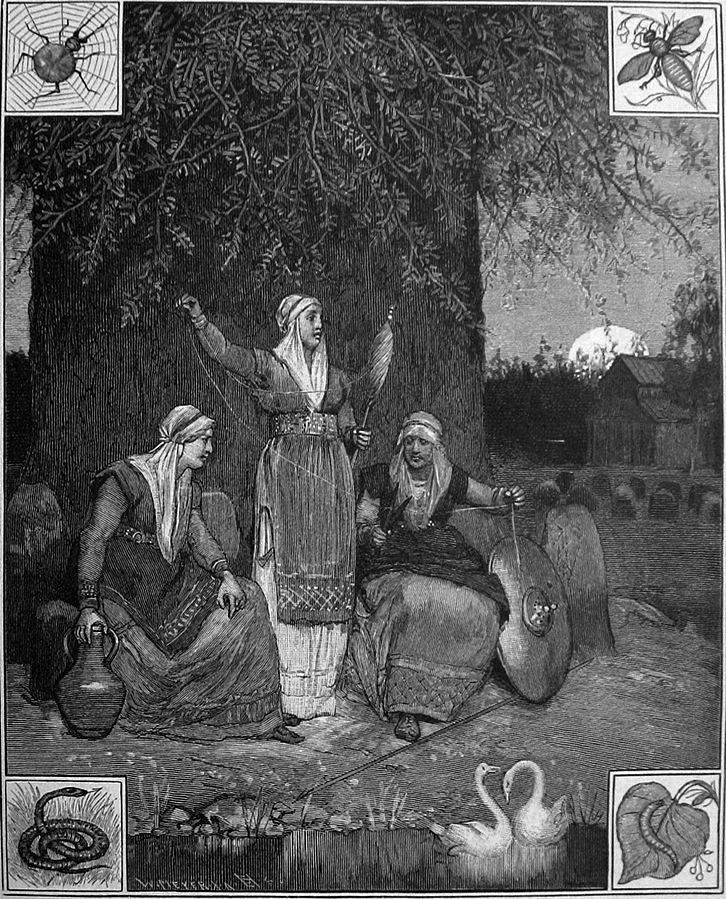

The Norns (Norse Mythology)

Similar to the Fates, they spin the threads of destiny by Yggdrasil, the World Tree. Represent Urd (Past), Verdandi (Present), Skuld (Future). Symbolism: Spinning reflects how past, present, and future are interwoven, shaping all existence.

Arachne (Greek Mythology)

A mortal woman skilled in weaving who challenges the goddess Athena. Transformed into a spider as punishment for her hubris. Symbolism: Spinning/weaving reflects skill, creation, artistry — but also pride, defiance, and transformation.

Spinning as Broader Symbolism:

Creation — Spinning fibers into thread mirrors crafting reality from raw chaos.

Time & Continuity — Threads represent the continuous flow of life and history.

Fate & Control — The spinner holds power over destinies.

Transformation — Spinning materials into new forms symbolizes metamorphosis.

The spinning wheel and the millstone each carry rich symbolism, both individually and when compared. Here’s a breakdown of what they symbolize and how their meanings contrast or complement one another:

Spinning Wheel – Symbolism

Creation: The act of spinning raw fibers into thread symbolizes creativity and birth

Feminine Energy: Traditionally associated with women’s domestic labor and maternal roles.

Fate and Destiny: In mythology (e.g., the Fates in Greek myth), spinning controls the thread of life.

Time and Continuity: The constant spinning motion mirrors the cycle of time and life’s continuity.

Peace and Patience: Especially in Gandhi’s use, the spinning wheel (charkha) represents nonviolence, self-reliance, and simplicity.

Millstone – Symbolism

Burden or Weight: “A millstone around one’s neck” suggests*a heavy responsibility or punishment. |

Labor and Industry | Symbol of grinding work, sustenance, and survival—essential yet relentless.|

Judgment: In the Bible and other traditions, the millstone can symbolize divine justice.|

Transformation: Represents the breaking down of the raw into the refined (grain into flour).

Foundation: As a fixed element in work, it symbolizes stability and reliability. |

Spinning Wheel vs. Millstone – Symbolic Contrast

Light vs. Heavy: Light, delicate motion | Heavy, grinding force |

Creative vs. Destructive :Constructs thread from chaos | Destroys grain to create nourishment |

Feminine Creation: Womb-like symbolism (thread = life) | Earthy, grounding labor (grain = body/sustenance)|

Destiny vs. Duty:Tied to fate, myth, and spiritual identity | Tied to survival, labor, and physical need |

Together as Symbolic Pair

The spinning wheel and the millstone, when viewed together, can represent two fundamental aspects of human life:

Spinning Wheel = the soul’s journey, creativity, destiny, ideals

Millstone = the body’s needs, labor, sustenance, consequences

They also contrast idealism and practicality, or the lightness of creation with the weight of responsibility.

- Frisians and Their Connection to Frodi’s Mill

1. Shared Germanic Heritage

The Frisians are part of the wider Germanic cultural and linguistic group, closely related to: The Saxons,The Angles,The Jutes,The Norse (Scandinavians)

This shared heritage means:

- Many myths and themes—such as magical objects, fate, and heroic cycles—echo across Frisian and Norse traditions.

- Elements like grinding mills, sea-based legends, and the tension between prosperity and downfall appear in both.

2. The Frisian Sea and Salt Connection

- A prominent sea-faring people, the Frisians share with the Norse a deep mythology tied to the ocean.

- The “Why the Sea is Salty” folk motif, which evolved from the Frodi’s Mill myth in Norse culture, also appears in various Germanic and North Sea coastal traditions, including Frisian folktales.

- Some Frisian legends explain natural phenomena like tides, storms, and saltwater through lost magical objects or ancient curses—conceptually similar to the Grotti mill at the bottom of the sea.

3. Frisian Freedom and Frodi’s Tyranny

- In Frisian identity, the concept of Frisian Freedom (the belief in self-rule and resistance to tyranny) is central.

- Frodi’s legend is a cautionary tale about greedy, oppressive rulers leading to inevitable downfall—this moral aligns with Frisian traditions that emphasize freedom, justice, and resistance to foreign or unjust rule.

- Some medieval sources tie Frisians mythologically to heroic, semi-legendary figures like Friso, who stands for liberation and seafaring prowess—traits that mirror opposition to rulers like Frodi in myth.

4. Possible Migration Myths

- Some medieval chronicles suggest legendary migrations from Troy or the East, connecting Frisians and Danes. Though these are more legendary than historical, they reflect shared myth-making patterns.

- This link offers a mythological space where Frisian sailors, Norse kings, and magical objects like Grotti could coexist in oral storytelling.

Summary: Is Frodi’s Mill Part of Frisian Myth?

Directly? — No confirmed, native Frisian version of Frodi’s Mill survives in historical records.

Indirectly? — Yes, through shared mythology, coastal folklore, and cultural exchanges across the North Sea during the Viking Age.

Themes of: Sea legends (salt, sunken treasures)- Resistance to oppression (Frodi’s downfall vs. Frisian Freedom) – Shared Germanic cosmology : All create strong parallels.

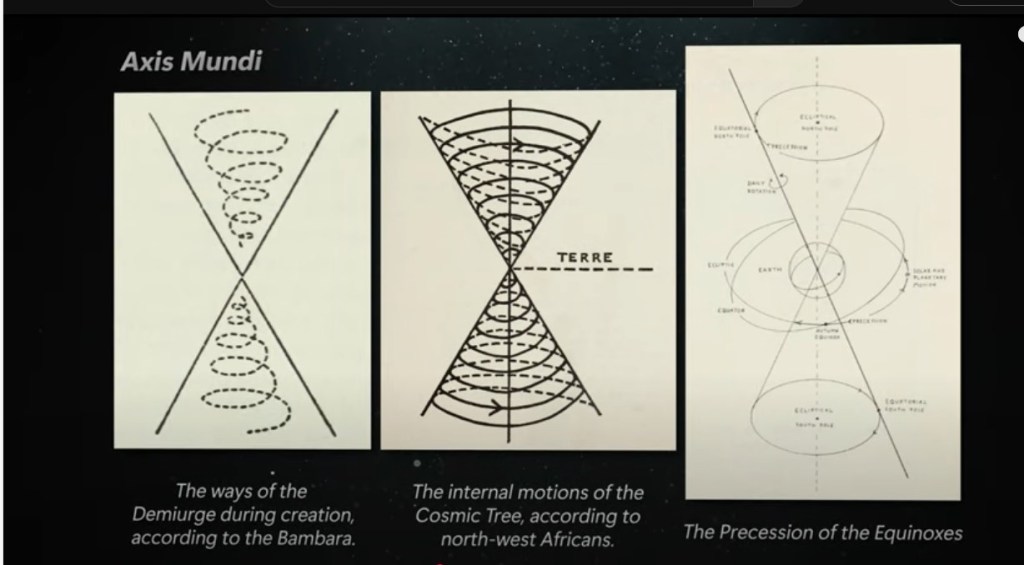

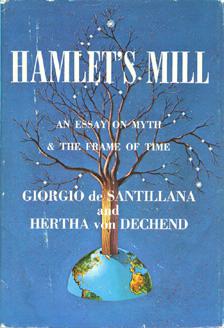

- Hamlet’s Mill:

Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay on Myth & theFrame of Time (first published by Gambit Inc.,

Boston, 1969), later Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay Investigating the Origins of Human

Knowledge and Its Transmission Through Myth, by Giorgio de Santillana, a professor of the

history of science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, MA, US, and Hertha von Dechend, a professor of the history of science at Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität in Frankfurt, Germany, is a nonfiction work of history of science and comparative mythology, particularly in the subfield of archaeoastronomy. It is primarily about the possibility of a Neolithic era or earlier discovery of axial precession and the transmission of that knowledge in mythology.

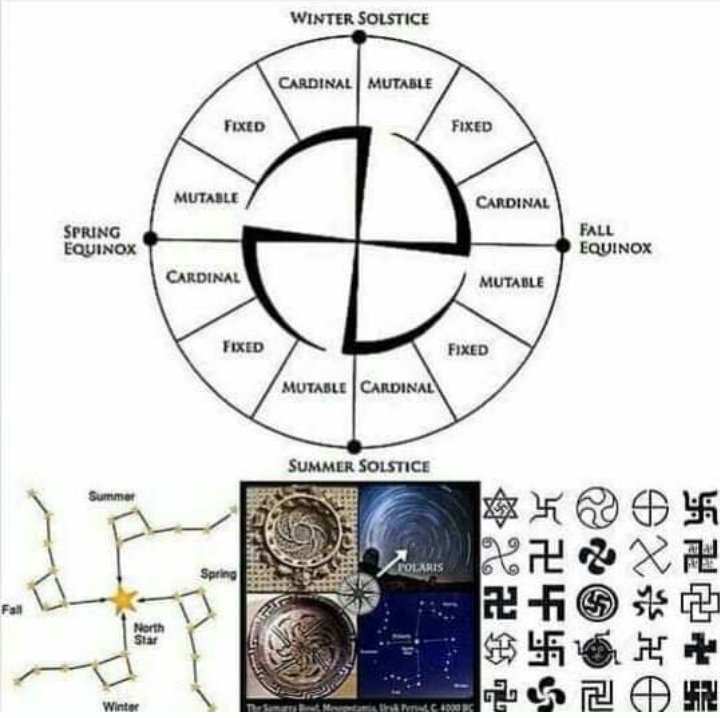

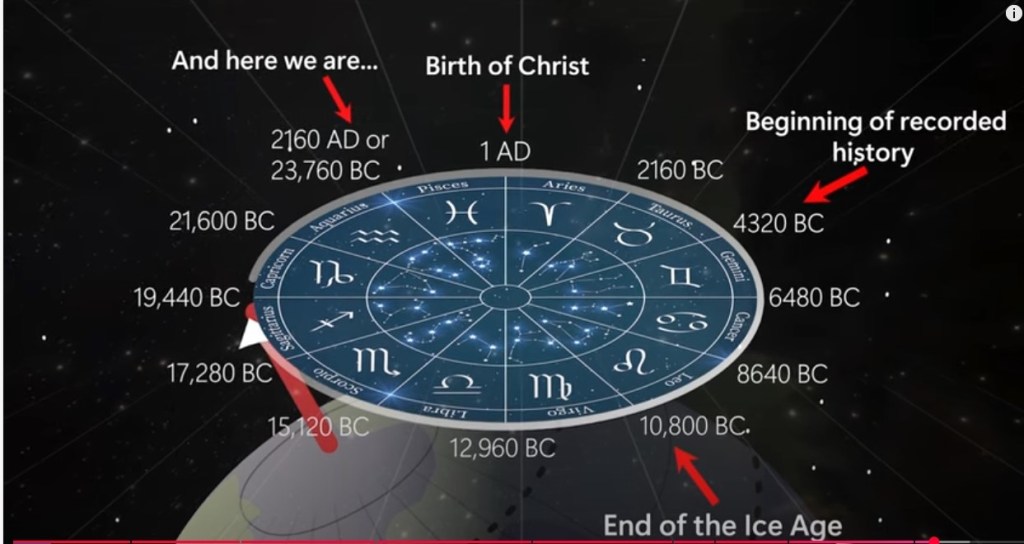

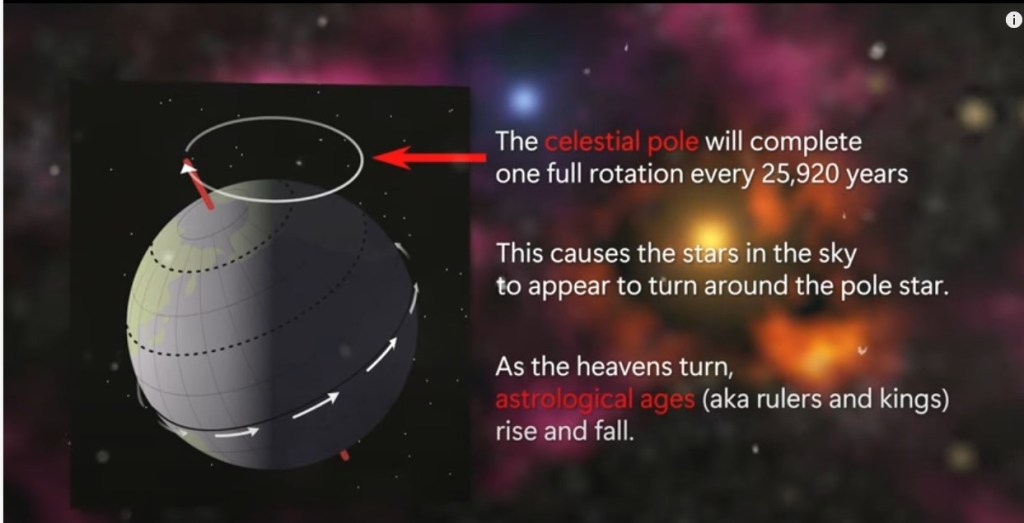

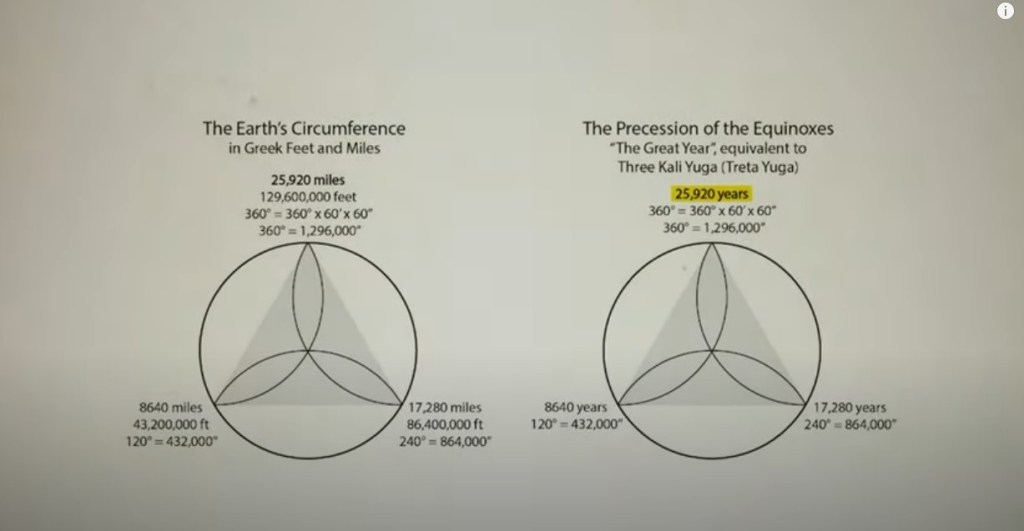

The main theses of the book include (1) a late Neolithic or earlier discovery of the precession of the equinoxes,2 an associated long-lived megalith building late Neolithic civilization that made astronomical observations sufficient for that discovery in the Near East,[2] and (3) that the knowledge of this civilization about precession and the associated astrological ages was encoded in mythology, typically in the form of a story relating to a millstone and a young protagonist.

This last thesis gives the book its title, “Hamlet’s Mill”, by reference to the kenning Amlóða kvern recorded in the Old Icelandic Skáldskaparmál.

The authors claim that this mythology is primarily to be interpreted as in terms of archaeoastronomy and they reject, and in fact mock, alternative interpretations in terms of fertility or agriculture.

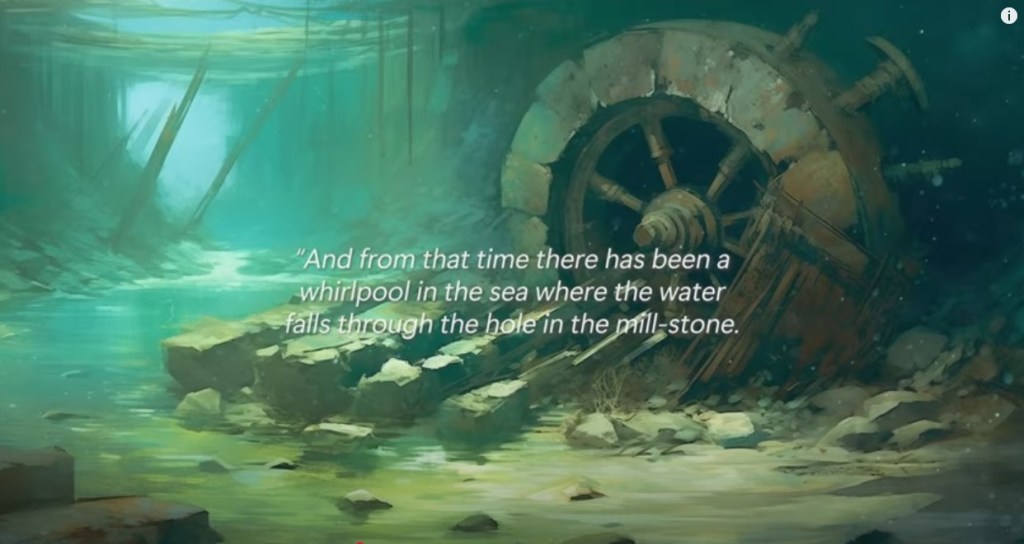

The book’s project is an examination of the “relics, fragments and allusions that have survived the steep attrition of the ages”. In particular, the book centers on the mytheme of a heavenly mill which rotates around the celestial pole and is associated with the maelstrom and the Milky Way.

The authors argue for the pervasiveness of their hypothetical civilization’s astronomical ideas by selecting and comparing elements of global mythology in light of hypothetical shared astronomical symbolism, especially among heavenly mill myths, heavenly milk-churn myths, celestial succession myths, and flood myths.

Their sources include African myths collected by Marcel Griaule, the Persian epic Shahnameh, the Classical mythology of Plato, Pindar, and Plutarch, the Finnish epic Kalevala, the eddas of Norse mythology,] the Hindu Mahabharata,[ Vedas,] and Upanishads,] Babylonian astrology, and the Sumerian Gilgamesh and King List. Read here

- WHY THE SEA IS SALTY.

FROTHI, king of the Northland, owned some magic millstones. Other millstones grind corn, but these would grind out whatever the owner wished, if he knew how to move them. Frothi tried and tried, but they wouldm not stir.

“Oh, if I could only move the millstones,” he cried, “I would grind out so many good things for my people. They should all be happy and rich.”

One day King Frothi was told that two strange women were begging at the gate to see him.

“Let them come in,” he said, and the women were brought before him.

“We have come from a land that is far away,” they said. “What can I do for you?” asked the king. “We have come to do something for you,” answered the women. “There is only one thing that I wish for,” said the king, “and that is to make the magic millstones grind, but

you cannot do that.” “Why not?” asked the women. “That is just what we have come to do. That is why we stood at your gate and begged to speak to you.”

Then the king was a happy man indeed. “Bring in the millstones,” he called. “Quick, quick! Do not wait.” The millstones were brought in, and the women asked, “What shall we grind for you?” “Grind gold and happiness and rest for my people,” cried the king gladly.

The women touched the magic millstones, and how they did grind! “Gold and happiness and rest for the people,” said the women to one another. Those are good wishes.”

The gold was so bright and yellow that King Frothi could not bear to let it go out of his sight. “Grind more,” he said to the women. “Grind faster. Why did you come to my gate if you did not wish to grind?” “We are so weary,” said the women. Will you not let us rest?” “You may rest for as long a time as it needs to say ‘Frothi,’” cried the king, “and no longer. Now you have rested. Grind away. No one should be weary who is grinding out yellow gold.” “He is a wicked king,” said the women. “We will grind for him no more. Mill, grind out hundreds and hundreds of strong warriors to fight Frothi and punish him for his cruel words.” The millstones ground faster and faster. Hundreds of warriors sprang out, and they killed Frothi and all his men.

“Now I shall be king,” cried the strongest of the warriors. He put the two women and the magic millstones on a ship to go to a far-away land. “Grind, grind,” he called to the women.

“But we are so weary. Please let us rest,” they begged.

“Rest? No. Grind on, grind on. Grind salt, if you can grind nothing else.”

Night came and the weary women were still grinding. “Will you not let us rest?” they asked.

“No,” cried the cruel warrior. Keep grinding, even if the ship goes to the bottom of the sea.” The women ground, and it was not long before the ship really did go to the bottom, and carried the cruel warrior with it. There at the bottom of the sea are the two millstones still grinding salt, for there is no one to say that they must grind no longer. That is why the sea is salty.

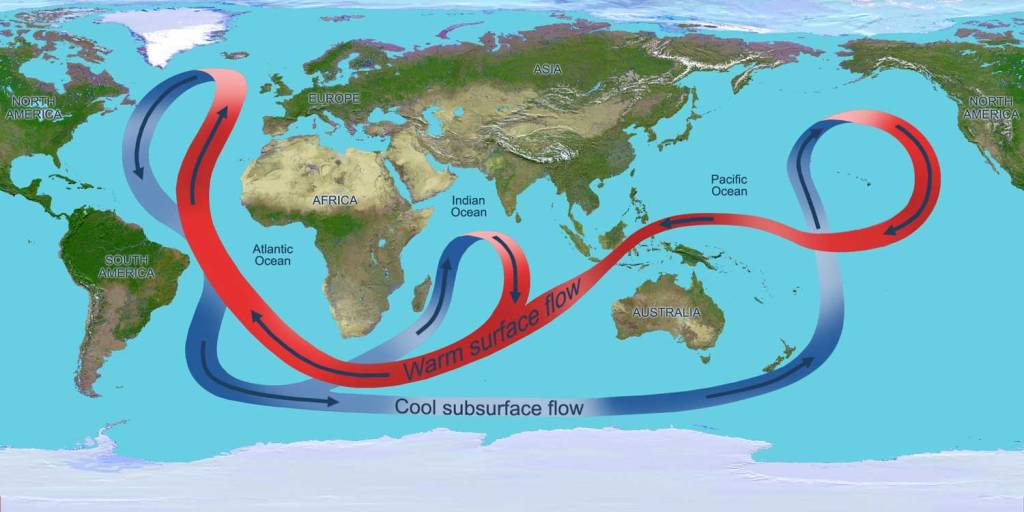

Salt in the ocean comes from two sources: runoff from the land and openings in the seafloor.

Rocks on land are the major source of salts dissolved in seawater. Rainwater that falls on land is slightly acidic, so it erodes rocks. This releases ions that are carried away to streams and rivers that eventually feed into the ocean. Many of the dissolved ions are used by organisms in the ocean and are removed from the water. Others are not removed, so their concentrations increase over time.

Another source of salts in the ocean is hydrothermal fluids, which come from vents in the seafloor. Ocean water seeps into cracks in the seafloor and is heated by magma from the Earthʼs core. The heat causes a series of chemical reactions. The water tends to lose oxygen, magnesium, and sulfates, and pick up metals such as iron, zinc, and copper from surrounding rocks. The heated water is released through vents in the seafloor, carrying the metals with it. Some ocean salts come from underwater volcanic eruptions, which directly release minerals into the ocean.

Salt domes also contribute to the ocean’s saltiness. These domes, vast deposits of salt that form over geological timescales, are found underground and undersea around the world. They are common across the continental shelf of the northwestern Gulf of America.

Two of the most prevalent ions in seawater are chloride and sodium. Together, they make up around 85 percent of all dissolved ions in the ocean. Magnesium and sulfate make up another 10 percent of the total. Other ions are found in very small concentrations. The concentration of salt in seawater (salinity) varies with temperature, evaporation, and precipitation. Salinity is generally low at the equator and at the poles, and high at

mid-latitudes. The average salinity is about 35 parts per thousand. Stated in another way, about 3.5 percent of the weight of seawater comes from the dissolved salts.

This model shows some of the cause and effect relationships among components of the

Earth system related to ocean circulation. While this model does not depict the ocean

circulation patterns that results from atmospheric wind and density differences in water

masses, it summarizes the key concepts involved in explaining this process

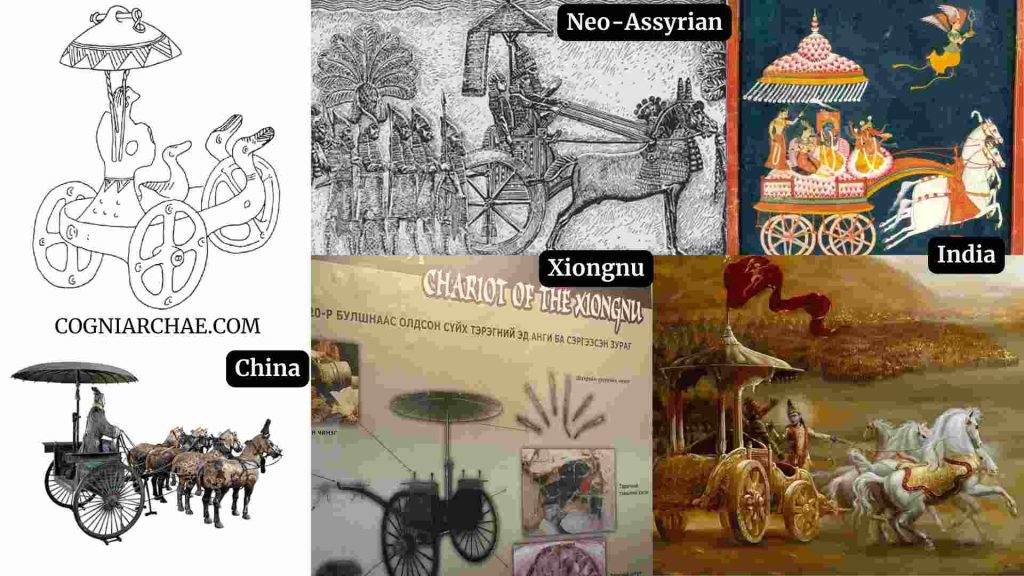

Note: The Dupljaja Chariots: Bronze Age Vehicles of the Gods

By Cogniarchae

Discovery and Context

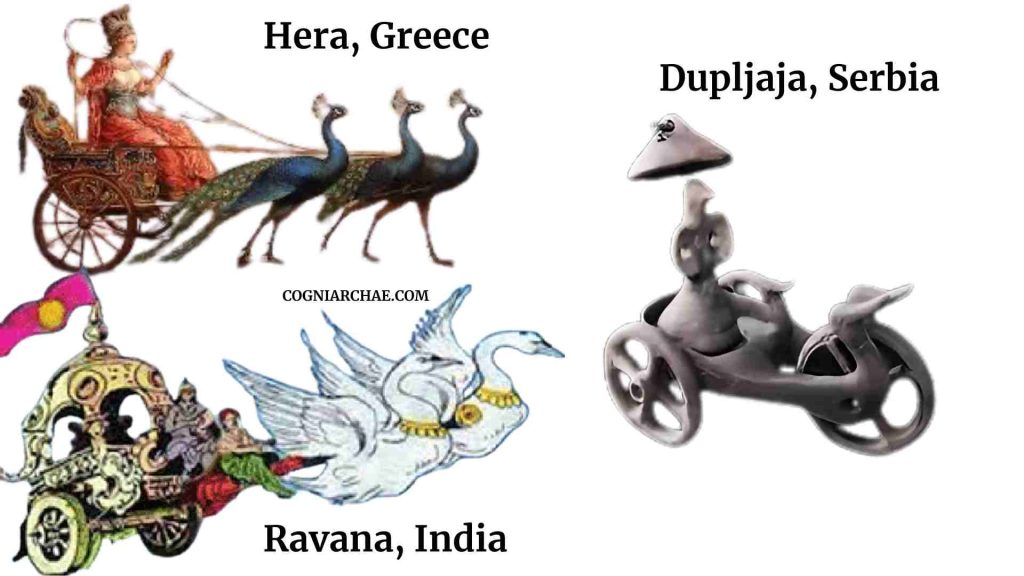

In northern Serbia, two ceramic chariot models from the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600–1200 BC) were unearthed in the village of Dupljaja, made in the Dubovac–Žuto Brdo / Garla Mare pottery tradition.

Their rotating wheels and worn surfaces prove active use — ritual or otherwise — and their design shows symbolic intent.

Each chariot bears a human figure — stylized and bird-faced (or with a bird mask). At least one figurine is likely male, with male genitalia under the skirt. Both are adorned with solar symbols such as the swastikas, circles and spirals.

The rich symbolism behind these artefacts has never been fully unraveled. It’s time we changed that.

The Umbrella Canopy — A Royal and Divine Symbol

The canopy marks the rider as sovereign or divine.

This arched canopy on a chariot is non-existent in European Bronze Age art but common in Vedic, Mesopotamian, and Assyrian iconography, where umbrellas signify royalty and divinity.

Vedic texts describe Aśvin-s, Indra, and Arjuna in covered chariots, symbols of prestige and divine authority.

The Dupljaja chariot is among the oldest known depictions of this kind of chariot anywhere in the world.

This Aryan tradition still lives in India, Cambodia, and Thailand through royal processions.

The Way of the Chariots

How chariots conquered the world.

Most historians and archaeologists attribute the introduction of chariots to the Indian subcontinent to Indo-Aryan–speaking groups who arrived during the late 3rd to early 2nd millennium BC.

Here’s the outline of what is known (and debated):

1. Archaeological record

• The earliest direct chariot finds in South Asia come from Sinauli (Uttar Pradesh), dated roughly to 2000–1800 BC. These were burials with solid-disk wheels and a pole for yoking animals. Whether they were true spoked-wheel war chariots or more like carts is still debated.

• True spoked-wheel chariots—lighter, faster vehicles associated with horse warfare—appear in the Near East and Central Asia around 2000 BC, linked to the Sintashta–Petrovka culture in the Eurasian steppe.

2. Linguistic evidence

• Vedic Sanskrit has an Indo-European chariot vocabulary (ratha, chakra, ashva, etc.) that closely matches cognates in other ancient Indo-European languages, suggesting a shared steppe origin.

• This points to chariots entering India alongside Indo-Aryan migrants from the north-west, via Central Asia and the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) region.

3. Historical interpretation

• Most scholars see the Indo-Aryan migration (~2000–1500 BC) as the vector for introducing true horse-drawn, spoked-wheel chariots into India.

• Some Indian archaeologists propose that chariots were locally developed or introduced earlier via trade from the Near East, citing the Sinauli finds. This is controversial because those vehicles may have been ox-drawn and solid-wheeled, not the lightweight steppe war chariot.

4. Likely route

Eurasian steppe (Sintashta/Andronovo) → Central Asia/BMAC → north-west India (Punjab/Haryana) → spread into the Vedic cultural sphere.

However, some of the oldest known, Neolithic representations of wheeled vehicles come from Anatolia and the Balkans.

Four-Spoked wheels

One of the earliest form of wheels

With their four-spoked wheels, the Dupljaja chariots occupy a distinct branch on the evolutionary tree of wheel design:

1. Pre-spoke era (before ~2200 BC)

Solid wheels dominate — heavy, disk-shaped, made from planks.

Common in Mesopotamia, Indus Valley, and early Anatolia.

Used for ox-drawn carts, not fast warfare.

2. Early spoked wheels (2200–2000 BC)

First experiments with many spokes (6, 8, sometimes more) appear in the Near East and Caucasus.

Evidence:

Middle Elamite cylinder seals (Iran) — show carts with spoked wheels.

Maikop & Trialeti cultures — solid and possibly proto-spoked examples.

Likely too heavy for true chariot speed.

3. Four-spoke revolution (c. 2000–1900 BC)

Earliest secure archaeological finds:

Sintashta (Russia) – Kurgans 1, 5, and others show two-wheeled chariots with exactly four wooden spokes per wheel.

Krivoye Ozero and Arkaim – similar construction.

Wheels about 80–90 cm in diameter, hubs with axle sleeves, lightweight frames.

Function: Fast, maneuverable, horse-drawn vehicles for warfare and prestige.

Importance: This design dramatically reduced weight and allowed higher speeds.

4. Spread & diversification (1900–1500 BC)

West: Reaches Hittites & Near East (c. 1800 BC) — they often switch to six-spoke wheels for added strength on rough terrain.

South: Passes through BMAC and Indo-Iranian migration routes.

East: By ~1700–1500 BC, Indo-Aryan groups bring light four-spoke chariotsinto the Punjab and upper Ganges region (Rigvedic ratha).

5. Decline of the four-spoke standard

In most regions (including India), six- and eight-spoke wheels become common by the Late Bronze Age.

Reasons: Stronger under stress, especially for heavier loads or rough ground.

Four-spoke wheels remain in ceremonial or specialized uses.

The Third Wheel Mystery

The third wheel is deliberate — and may even hold sacred meaning.

One of the Dupljaja chariots has three wheels. That’s unusual. Real chariots had two, for speed and maneuverability. This model adds a third at the front, between the draught poles.

This third wheel is not decorative: it rotates and shows wear, but unlike the others, it’s mismatched in material and design — likely reused or added later. It has been suggested that the third wheel was added to prevent the model from tipping over.

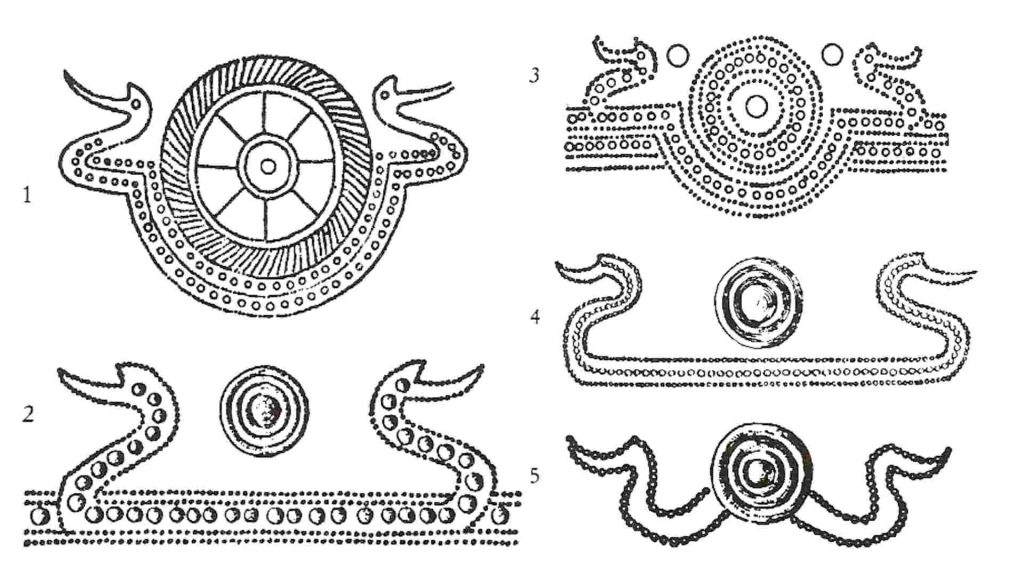

However, three-wheeled chariots — though rare — do appear in some of the earliest chariot-related myths. In the Ṛgveda, the gods known as the Aśvin-s — divine twins associated with dawn and healing — are said to ride in a flying three-wheeled chariot (tricakra).

This chariot is described as “brilliant, rolling lightly on its three wheels,” and “at whose yoking the Dawn was born.” It can move “without horses, without reins,” and is sometimes drawn by birds or compared to a bird in flight. One verse calls it “three-benched, three-wheeled, as quick as thought,” adorned with three metals.

In Sūryā’s Bridal (RV 10.85), the chariot appears at the marriage of the Sun’s daughter, Sūryā — a union rich in themes of renewal and fertility. Here, the third wheel becomes a mystery: the Brahmans know only two, while the third is hidden, known only to those “skilled in highest truths.”

This imagery fits into a much broader Indo-European dawn myth cycle: Uṣas, the Vedic dawn goddess, rides a chariot drawn by red cows or horses, heralding renewal; Eos in Greek myth (and her Roman counterpart Aurora) drives a chariot across the sky, often linked to Venus as the Morning Star.

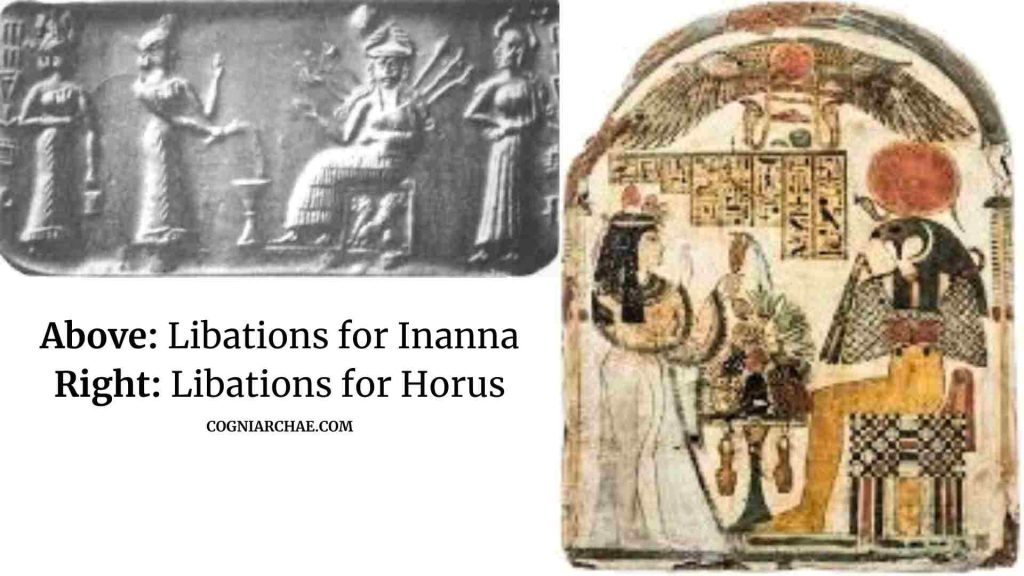

It also fits the widespread sacred marriage motif, where the union of divine figures brings fertility and cosmic order — from Sūryā’s wedding to the tales of Inanna and Dumuzi, Zeus and Hera, Hathor and Horus, and even in the Ramayana, where Rāvaṇa abducts Sītā in a flying chariot.

So, who is the chariot?

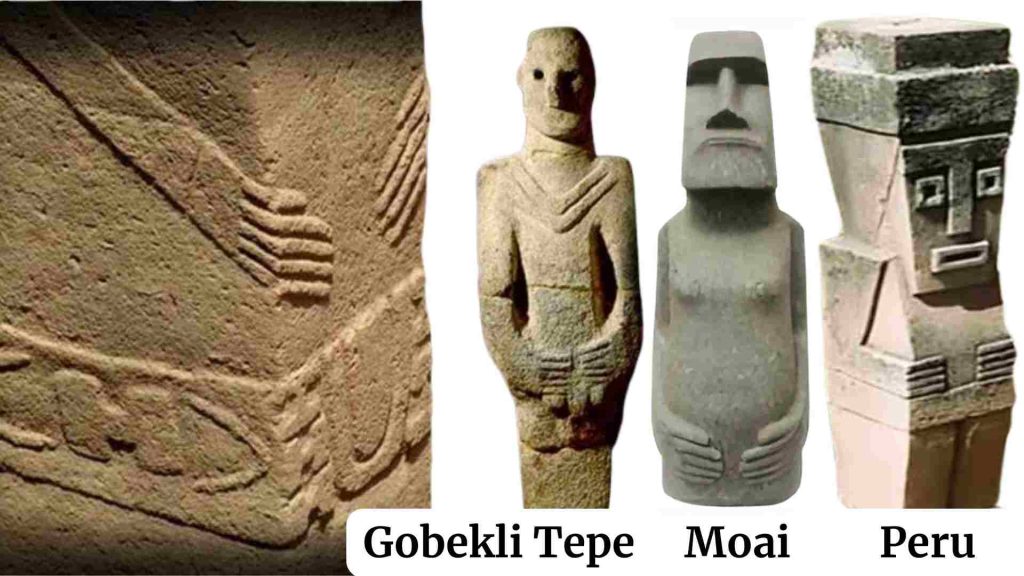

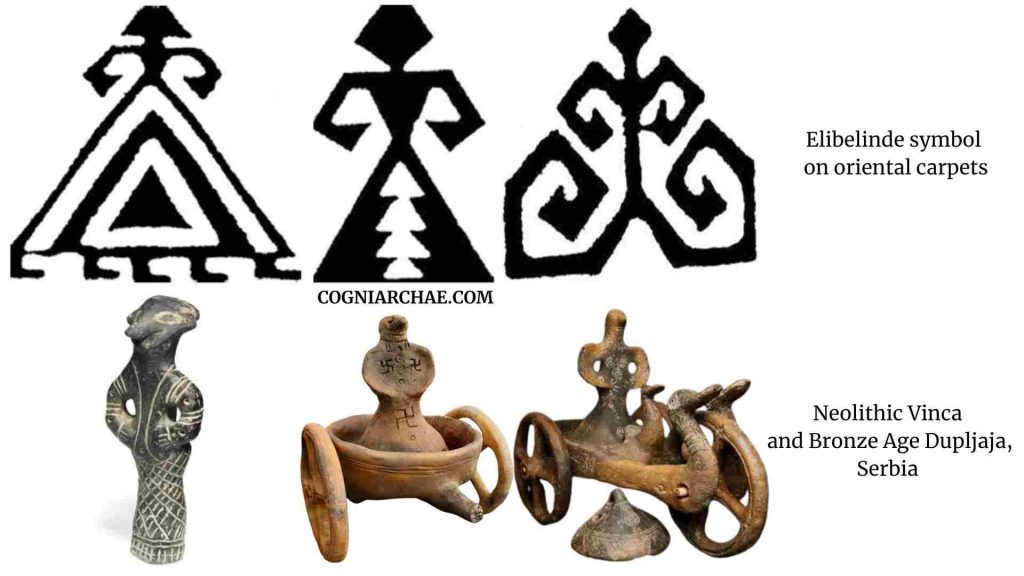

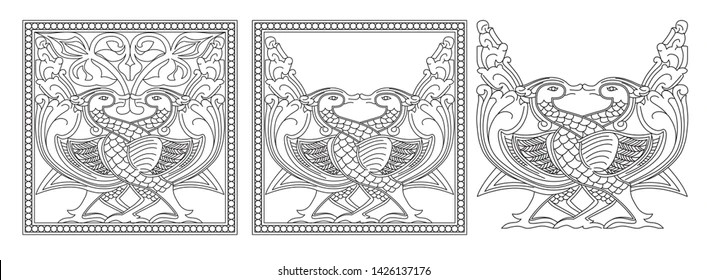

The Pose of Power — Elbows Akimbo / Elibelinde

A Mother Goddess stance — with deep Balkan roots.

The motif predates the Bronze Age, with examples found at Göbekli Tepe and in numerous megalithic cultures worldwide. Its widespread use was likely due to practicality — it is simply the easiest way to carve hands in stone.

The central figure stands hands-on-hips — elbows bent, hands resting on hips — radiating authority and embodied power.

In Neolithic pottery, this pose began to take on a new meaning and most commonly represented the Mother Goddess. Geographically, Dupljaja village lies at the very heart of the Neolithic Vinča culture. Within the Vinča culture (c. 5700–4500 BC), countless figurines — often depicting goddesses or priestesses — share this stance, some even bearing bird-like faces.

Furthermore, this motif is found in traditional Oriental carpet design, in the symbol known as “elibelinde” — literally “hands on hips” — representing womanhood, marriage, and creation.

The skirts depicted on these designes are very remeniscent of the one that Dupljaja figurines are wearing.

The Many Faces of the Bird-Headed Deity

Avian faces here are not artistic quirks — they carry divine and messenger roles.

Identifying the rider of the Dupljaja chariot is no simple task. Bird-faced deities once flourished across a vast cultural corridor — from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, through Cyprus and the Balkans, and as far east as the Indus Valley. Yet their attributes shift with time and place. Sometimes they appear as male, sometimes as female, and sometimes as beings whose gender is deliberately ambiguous.

They may embody the sun or the dawn, act as messengers between worlds, or serve as protectors of kings. In some traditions they preside over fertility and renewal; in others, they guide souls to the afterlife.

Bird-Headed Males

Take, for example, the Egyptian Horus — a falcon-headed god and one of the most ancient bird-men known to us — here shown in the same commanding pose as the Dupljaja figure.

His roles were many: sky-god, divine protector of the pharaoh, avenger of his father Osiris, and guarantor of order over chaos. Horus was also a god of war and hunting, whose keen falcon eyes saw all from above, yet he could be a patron of kingship and renewal, embodying the daily rebirth of the sun.

However, Horus was never depicted riding in a chariot in Egyptian art. On the other side of the world, though, the equally ancient Garuda was.

The famous stone chariot at the Hampi temple is dedicated to him, echoing the grand processions in which his image would have been paraded. Garuda’s role was that of a divine mount and loyal servant to Vishnu, a cosmic protector who could traverse heaven and earth with the speed of the wind. He was the slayer of serpents, the enemy of demons, and the unyielding guardian of dharma.

In Serbian medieval epic poetry, the grey falcon (sivi soko) is a divine messenger and guide between worlds. The same role was attributed to falcons in numerous steppe cultures of Eurasia.

At the same time, the female counterpart of the grey falcon is the titmouse bird (ptica sjenica), equally popular in Serbian epics. I believe this word is a direct cognate of the Sanskrit śyena (“falcon”), which was also one of the names of Garuda. Sjenica would therefore mean “female falcon.”

Bird-Headed Females

There will always be those who claim that all examples of bird-headed deities arose independently, making any search for a common theme pointless.

However, nothing could be further from the truth. As the following image shows, even male and female deities were sometimes depicted with identical iconography — clear evidence that shared motifs did exist.

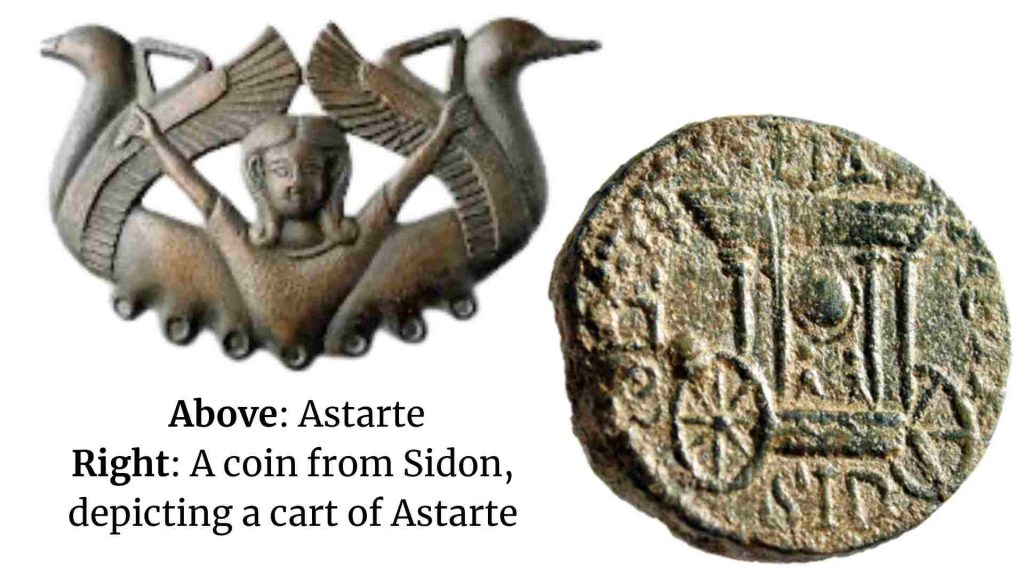

Astarte was a major goddess of the ancient Levant, especially among the Phoenicians, Canaanites, and later adopted by Egyptians. She sometimes combines avian facial features with the hands-on-hips pose and a chariot.

The above depiction of Astarte is very similar to the Solar Boat depictions from the Scandinavian Bronze Age.

Similarly, in Norse mythology, Freya rides a flying chariot drawn by two great cats. Freya, Inanna, and Astarte are all love-and-war goddesses linked to fertility and the planet Venus, embodying a shared archetype of beauty, power, and cosmic renewal, often depicted with ritual vehicles.

Note: See Mythology, Legends and Fairy Tales of Friesland

Frisian Craftmanship

In Slavic tradition, the goddess Vesna embodies youth, renewal, and spring’s triumph over winter’s death-spirit Morana. Particularly among South Slavs and East Slavs, Vesna is celebrated on March 22: villagers fashion clay or dough lark or swallow effigies, which are carried in song through the fields to summon her arrival and fertility.

In Slovenian lore, “vesnas” dwell atop mountains and descend in wooden carts in February, heard only by those attuned to their fate—an image highly resonant with the chariot‑travel motif found in Dupljaja and in Vedic dawn gods.

Hieros Gamos – Spring and Fertility

The Sacred Marriage of Heaven and Earth

Hieros gamos is an ancient ritual or mythic motif of a sacred marriage between a god and a goddess, symbolizing cosmic union, fertility, and the renewal of life.

In Serbia, March 22 holds a special significance. In Serbian Orthodox Christianity, it is celebrated as Mladenci (“the newlyweds”), falling just after the spring equinox. Beneath its Christian veneer, the day preserves a far older tradition — the hieros gamos.

While its official Orthodox meaning commemorates the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste, the older, pre-Christian layer celebrates the union of a newly married couple as a cosmic and agricultural renewal. Timed to the moment when day and night stand in balance and the light begins to grow, it echoes ancient Near Eastern and Indo-European traditions — from Inanna and Dumuzi to Zeus and Hera, or Sūryā and her divine suitors — where such unions ensured fertility and prosperity.

The gifts of honey, bread, and wine offered to the newlyweds recall offerings once meant to bless the land, the household, and the community at the threshold of spring.

The Celestial Twins and the Chariot

The key is in the stars

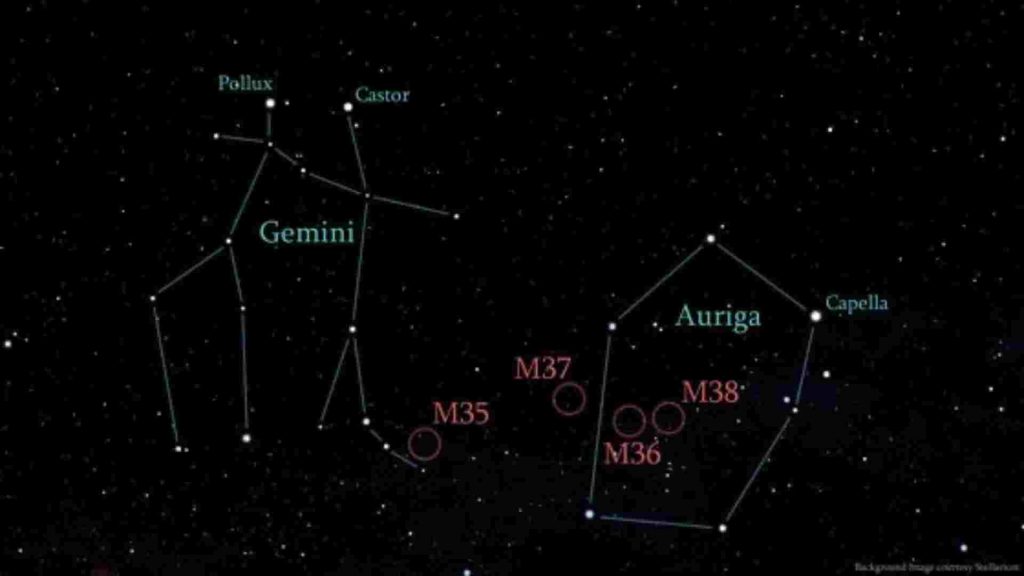

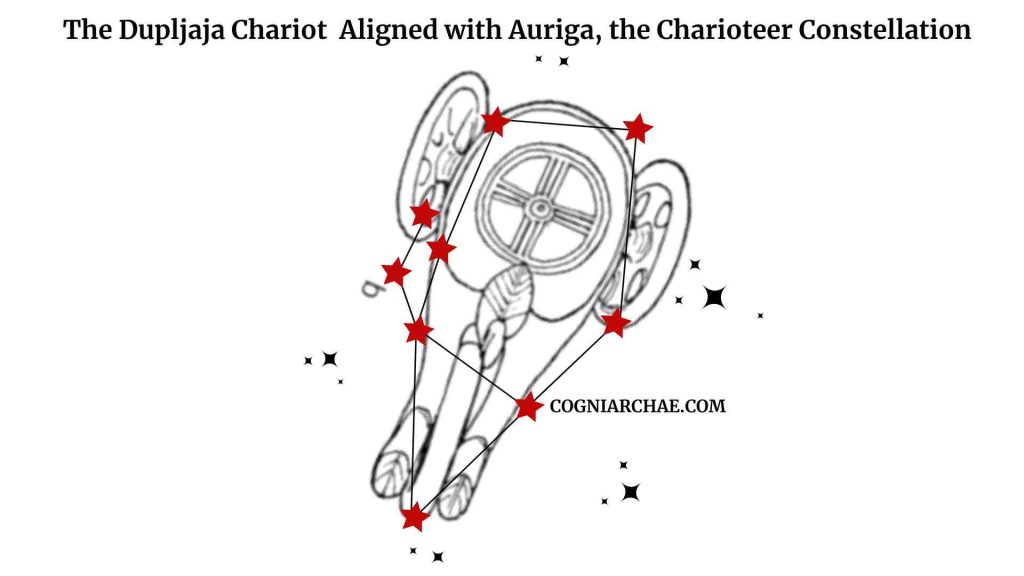

The Vedic Aśvin-s are not only mythic twins — they are also astronomical figures. The ancients probably identified them with the Gemini constellation, the divine twins. Their chariot, blazing and radiant, maps closely to Auriga, the charioteer constellation just above them in the sky.

Here’s a thought: the shape of the Dupljaja chariot bears an uncanny resemblance to the Auriga constellation. Could this celestial likeness be the very reason the ancients added a mysterious third wheel to the ritual model?

However, all of these mythological layers only align if the spring equinox occurs somewhere between the constellations of Gemini and Taurus.

This celestial pairing — Gemini (the twins) and Auriga (the chariot) — was especially significant during the spring equinox window of the 6th to 4th millennia BC, when these stars heralded the new year and marked the rebirth of the solar cycle in the ancient sky.

Therefore, this imagery wasn’t just symbolic — it was calendrical. The Aśvin-s, as dawn-riders, may have once functioned as timekeepers, their rising announcing the return of the spring, and the turning of the year.

The same symbolism is clearly present on the Dupljaja chariots.

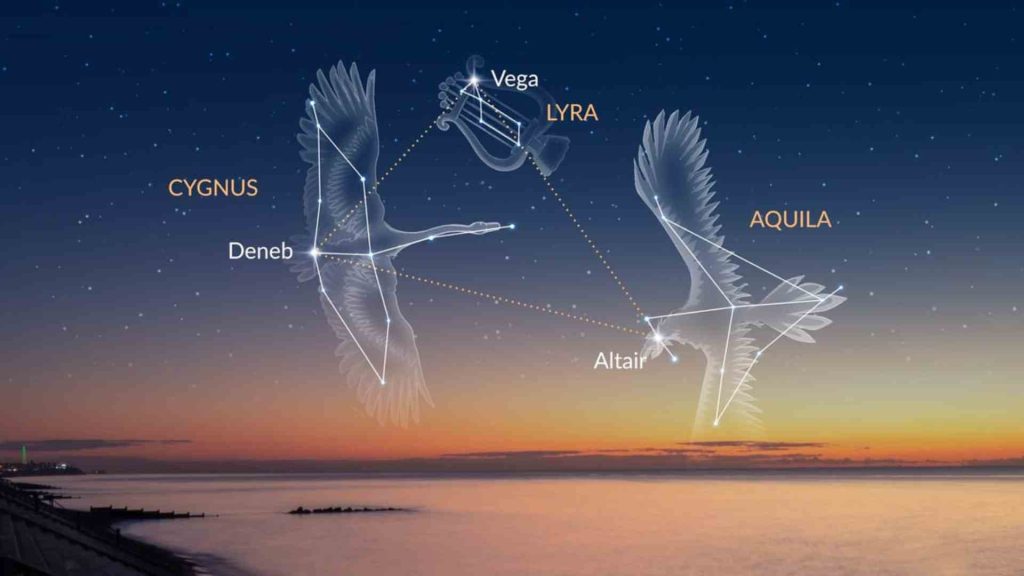

Moreover, looking at the opposite horizon from Gemini, the ancients would see three birds — Cygnus the Swan, Aquila the Eagle, and Lyra the Vulture.

Final Thoughts

Dupljaja chariot is a microcosm of ancient cosmology.

We may never know the myths that created the Dupljaja chariots, but their Mother Goddess stance, avian features, canopy, tricakra design, and echoes of ritual processions are all familiar.

These motifs existed in a continuum stretching from Neolithic Balkan worship to Vedic dawn hymns, Near Eastern sacred marriages, and Slavic seasonal rites.

My five cents is that what we see here is a Bronze Age echo of a much older Neolithic stellar myth and New Year rites, dating to a time when the spring equinox passed between Gemini and Taurus.

In ancient imagery, chariots usually carried moving objects — stars or planets. However, I don’t believe this was a solar symbol. More likely, these chariots carried the planets – originally Mercury, the ruler of the Gemini, and later Venus, who rules the Taurus. Indeed, Mercury, like the falcon, it is the swiftest of all planets, and its androgynous nature could explain the initial duality of the bird-faced deities.

These chariots were found on a cremation ground, but they were burried there after long and deliberate use. Therefore, I don’t believe that their role was to carry the sould to the afterlife, as some have suggested.

They are not relics of death, but a crafted symbol of hope, and the unbroken wheel of life that renews itself.

Look also: The Horse Sacrifice: a Self-Sacrifice for our Time

and The Androgyne: A Metaphysical, Linguistic and Anthropological View

and The double meaning of the Androgyne