It is the End of the World as We Know It – and we feel fine: The illustrations from Le Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur

Some of the most remarkable, wonderful and unsettling images of hell and damnation from the middle ages are found in a 15th century manual describing illustrations and are available to view here. This seems to have been the second volume of a larger, two part work, completed the apocalypse (the end of the world) produced by Carthusian monks in France known as Le Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur (The Book of the Vineyard of our Lord). Now held by the Bodleian LIbrary in Oxford its some time before 1463 in France. Its author and illustrators are unknown. It’s thought to be Carthusian because one illustration depicts two Carthusian monks.

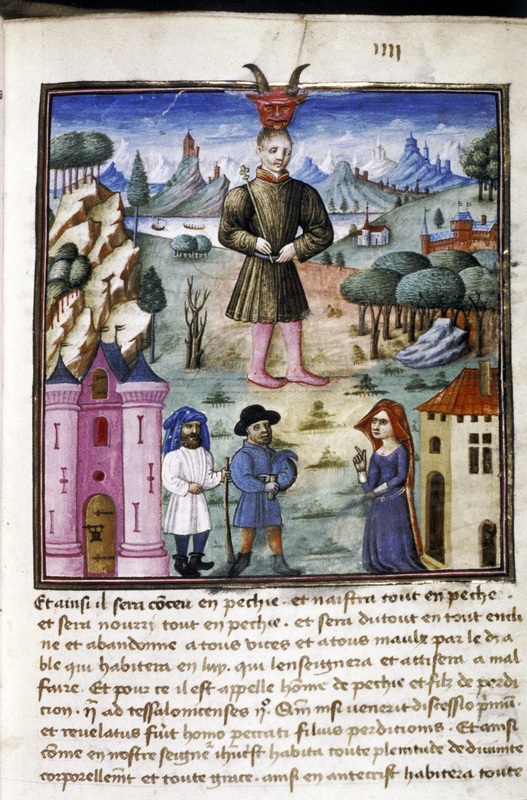

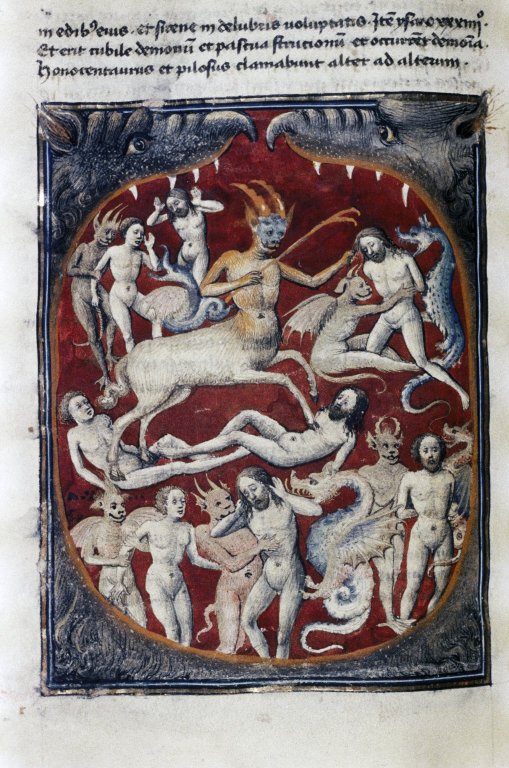

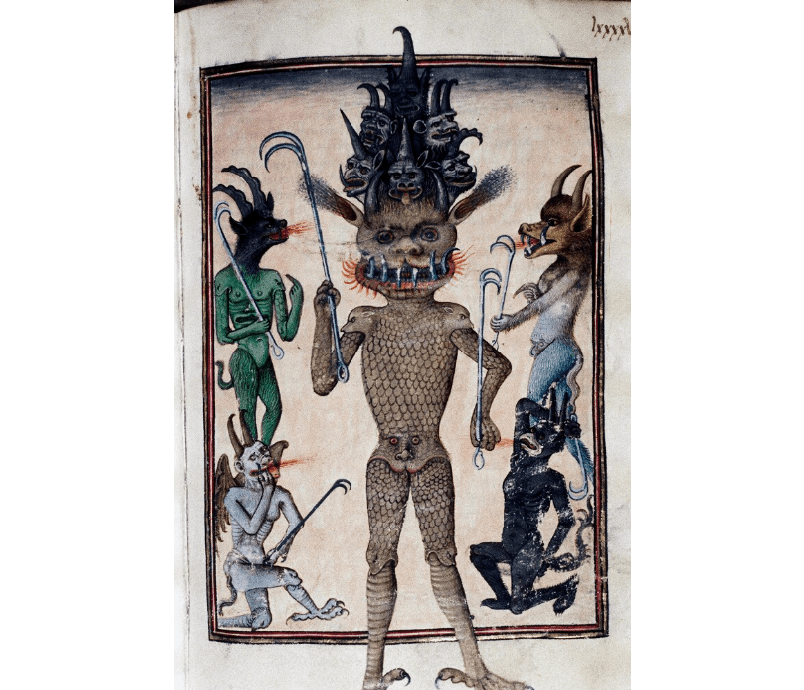

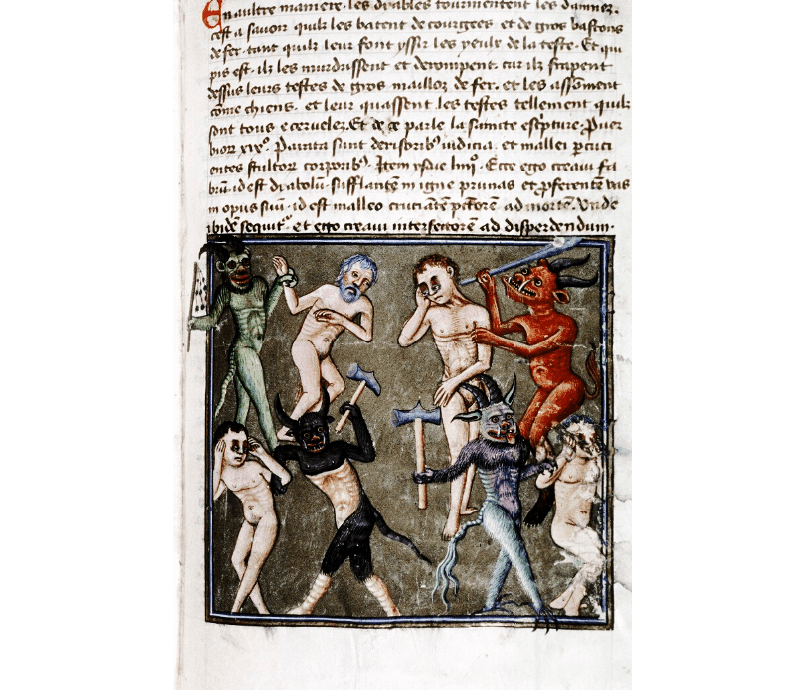

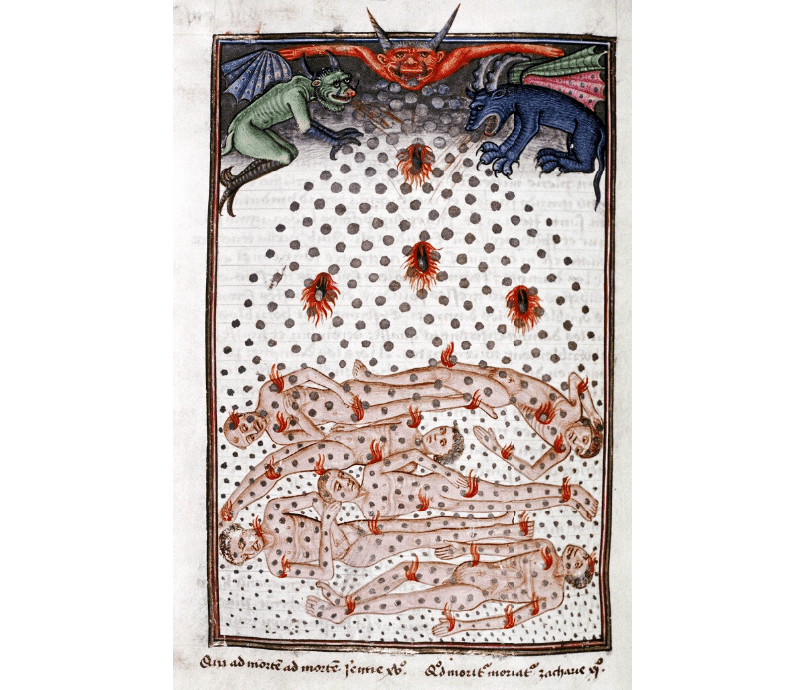

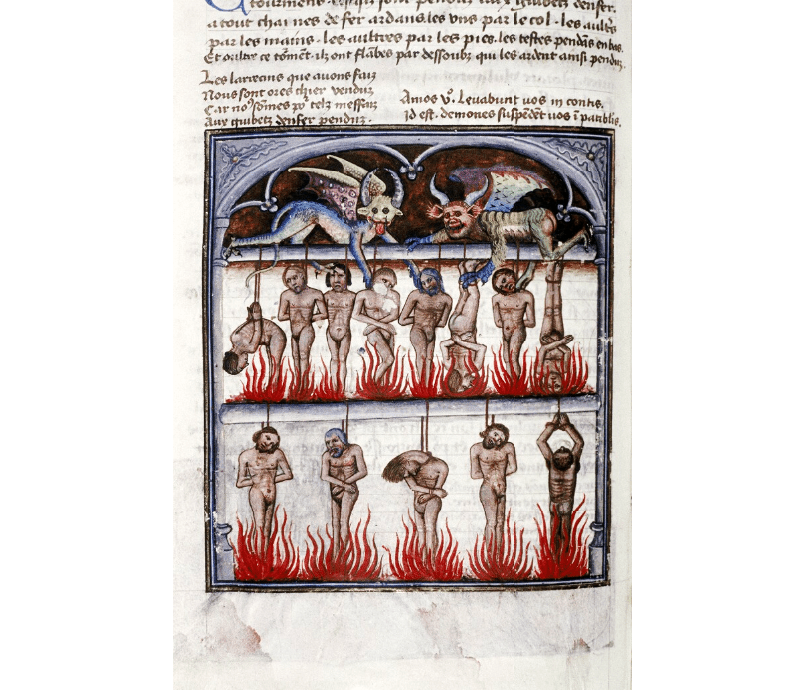

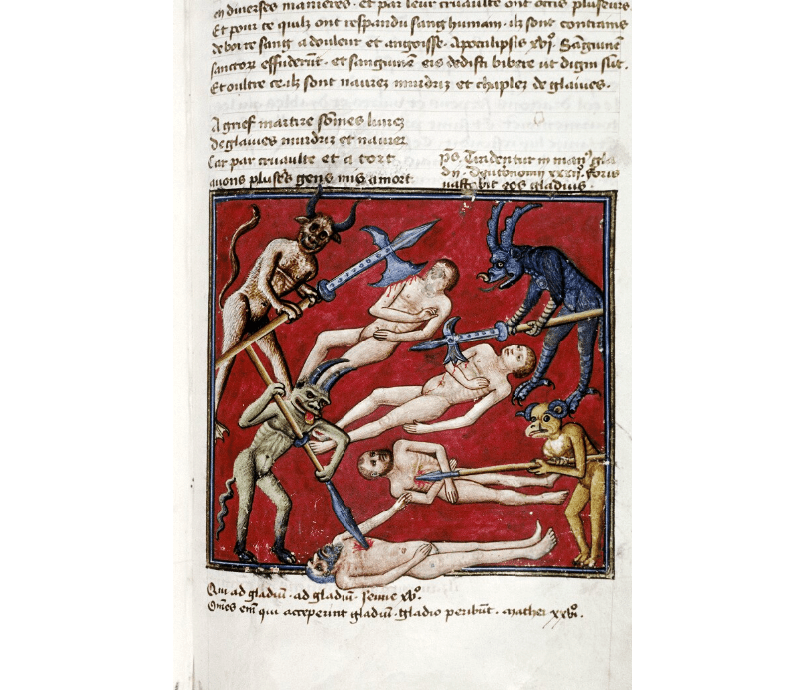

These images depict the Antichrist and his war on the Church, the signs of the coming of the end of the world, the Last Judgement and then, in full gory detail, the sufferings of the damned.

The whole point of this blog is to argue that our ideas of heaven and hell owe far more to the imaginations of writers and artists in the middle ages and Renaissance than to the bible and here we get a really good feel for the kinds of ideas that were shaping the thinking of Christians bout the afterlife at this time. They are fun, shocking, amusing and very, very interesting.

Will the real Antichrist please stand up?

The book begins with a description of the nature and activities of the Antichrist, who is shown here with his two faces, one revealing his true, devilish nature and a more acceptable ‘human’ face which proves attractive to the human population. See Inauguration of Total Ego-Madness at the Capitol

The book then portrays this creature in the different stages of his career as he seduces the world and turns the populations of earth against the Christian church. Interestingly, written a hundred years before the Reformation by Catholic monks, the Antichrist is depicted here, arriving in Jerusalem as a false pope!

With the Antichrist now in charge it’s not long before the persecution of the true followers of Christ (those who won’t bow down to the Antichrist) begins.

Thankfully, God has everything in hand and soon brings an end to the activities of the Antichrist.

Fifteen Signs

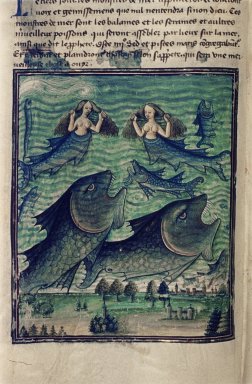

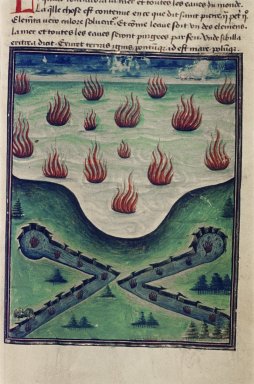

Following the destruction of the Antichrist comes the end of the world itself. First however, the population of earth have to endure 15 ‘signs’ of The End, each of them terrible enough in themselves. These are beautiful, striking images, full of imagination and, worryingly seem all too relevant to features of our own global crisis!

————————–

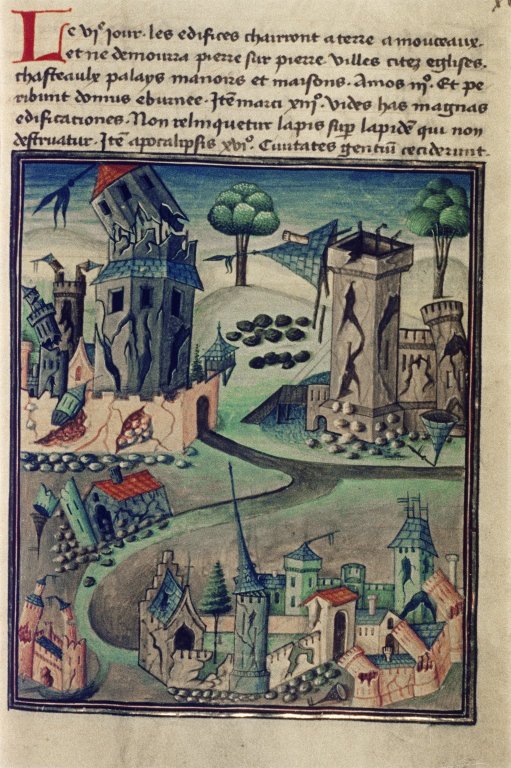

And so it goes on, with one world crisis after another. here ís the depiction of the cities and towns of mankind, their pride and joy, broken down and ruined

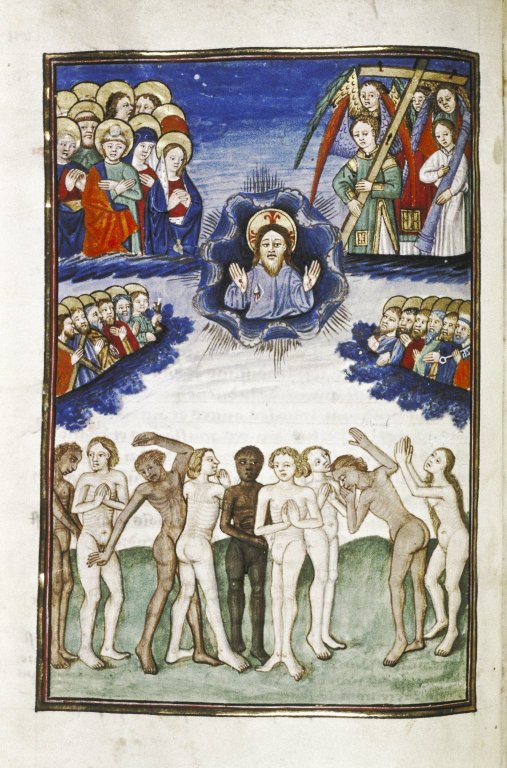

And then of course comes ‘The End’ and the great final judgement. After the world is flattened, earthquakes, the raising of the dead and the death of the living the angels blow their trumpets and all the dead are raised together to face judgement. This is depicted rather wonderfully as both the opening of the tombs (this is a bodily resurrection of course) and the emptying of Death, pictured as the mouth of the Leviathon (the great biblical sea monster) .

Standing under judgement

Christ appears in the sky/heavens attended by angels to judge the blessed and the damned. You can easily spot the damned – they are dark-skinned. I am not sure how relevant it is to judge a previous era in terms of concepts like racism that we use now. The damned were often associated with ‘the heathen’ (who were usually foreign) but here it could simply be a way of ‘spotting the difference’, with the darker shade a symbol of their wickedness. White is usually seen as a colour of purity. These associations of course raise their own issues about skin colour and its perception. Jesus of course is very ‘european’ and whiter than white!

As the women and the apostles pray for the souls of the dead, Christ judges them. The right arm is raised in blessing, the left stretched out in condemnation.

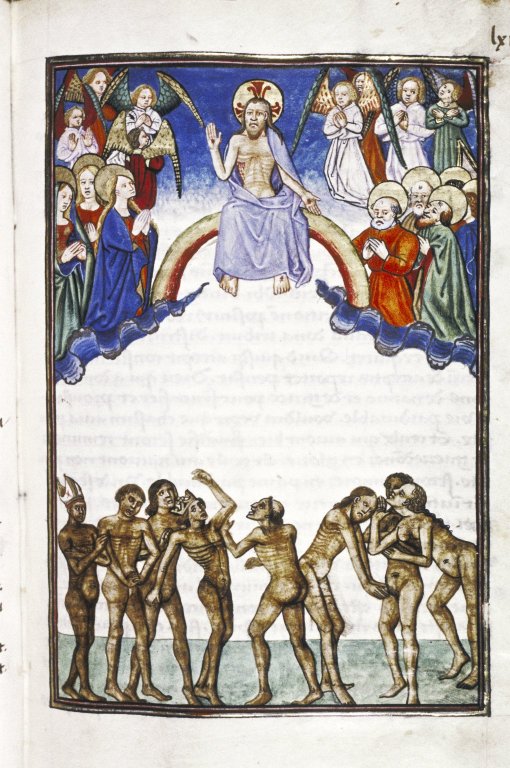

Jesus (all of him), perched precariously on a rainbow, prepares to sentence the damned among whom, it appears, are a pope and a king! Fol. 63r

But of course the judging must be fair and according to an ‘official’ standard, so scales are employed and Michael, the chief angel, is given the job of weighing the souls. This idea of the weighing of souls is not found in the New Testament but was an idea taken over by the church from Egyptian mythology. It became a stock feature of medieval and Renaissance depictions of the Last Judgement.

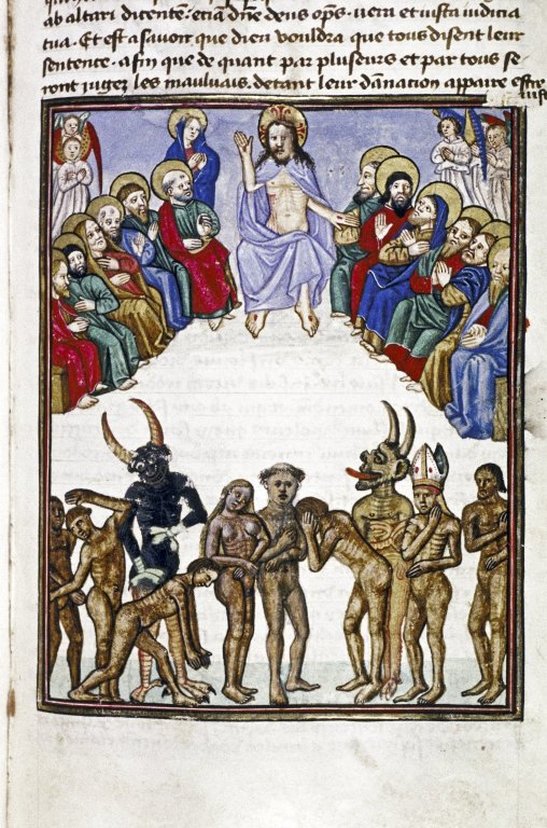

But Christ does not judge alone. After all he promised the 12 apostles that they would rule with him, so at the Last Judgement they will sit in judgement with him like a celestial 12 man jury.

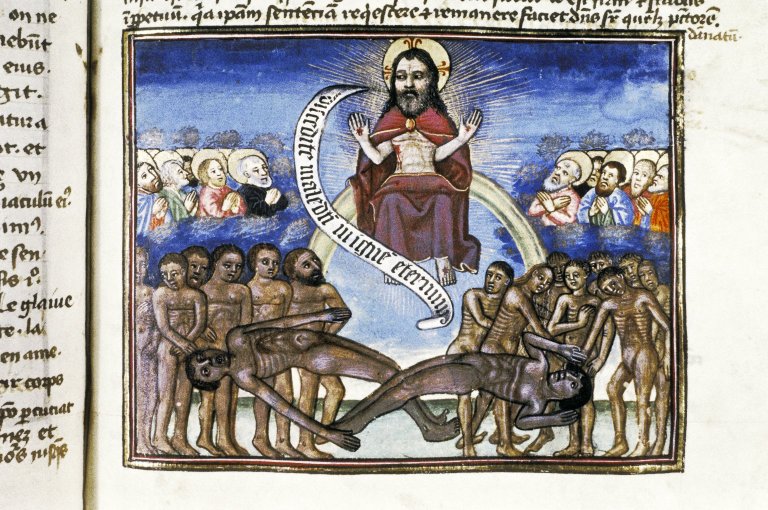

And so, at last, the souls have been weighed, the jury has deliberated and the sentence is passed. With the words “depart from me, accursed ones, into everlasting fire” (Matthew 25.41 Vulgate) Christ banishes the damned from his presence.

And so the Antichrist has been defeated, the end of the world has come and the dead have been raised (bodily please note!), some to everlasting life and some to everlasting damnation. For the monks reading this amazing book, the text and these marvellous illustrations would have both terrified them (after all, everyone involved seems to suffer) and reassured them. The various wars and rumours of wars, plagues, famines, earthquakes they experienced and knew of and the failures of popes, priests, kings and emperors could all be read, not as random, chaotic events without meaning, but as signs of The End, which the book told them was in the hands of Jesus, their Lord. They could find comfort and hope in that.

But that isn’t the end of the book. It goes on to describe in graphic detail the horrors awaiting those who are sentenced to perdition. The torments of the damned are portrayed in their full horror.

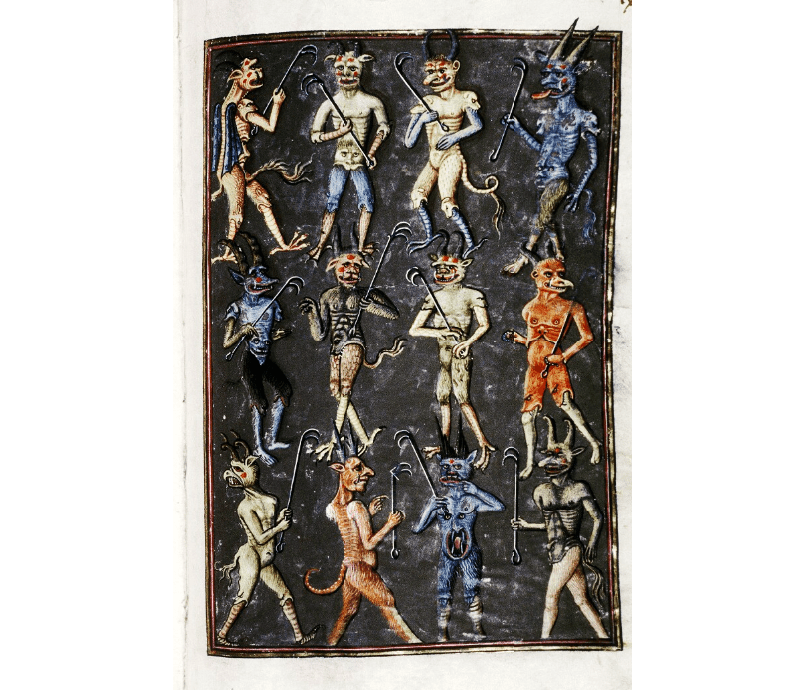

Following judgement the wicked and the devils are consigned together to the ‘pit’ of hell. The devils look rather pleased about it. From Le Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur. 15th century; France. Bodleian Library MS Douce 134 fol. 77v

In the previous post I looked at some of the illustrations from Le Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur, a 15th century French manual describing the end of the world, the last judgement and the punishment of the wicked in hell. It’s an amazing document and the illustrations are quite remarkable and beautiful. The illustrations show the activity of the Antichrist, the signs of the Apocalypse and the Last Judgement. After the Last Judgement the illustrations show in graphic detail the terrible punishments and tortures that lie in wait for the damned. In this post I want to show you these illustrations, not just to revel in the twisted imagination of these Renaissance monks as they imagined the unspeakable horrors of damnation (although I do!) but to think about what they tell us about the Renaissance view of sin. A warning before we begin – this is not for the faint hearted or the sqeamish!

Being ‘sent down’.

The damned are ‘sent down’ to hell through what appears to be a giant mouth-shaped hole in the ground. This imagery isn’t surprising as both death and hell (or Sheol/Hades) are pictured as living monsters in the bible and in subsequent Christian imagery. The damned are accompanied by the demons who will torment them for the rest of eternity who seem very pleased at the prospect! The press of bodies and the confusion of orientation symbolises the chaotic nature of life without God. So anyone looking at our house would conclude . . . .

Here is a close-up of the hellsmouth and we can see some of the beasts and monsters who will be tormenting the damned. This is clearly by a different illustrator.

First, it seems, the damned are cooked in ovens for a while. The forks seem very impressive!

- The Seven Deadly Sins

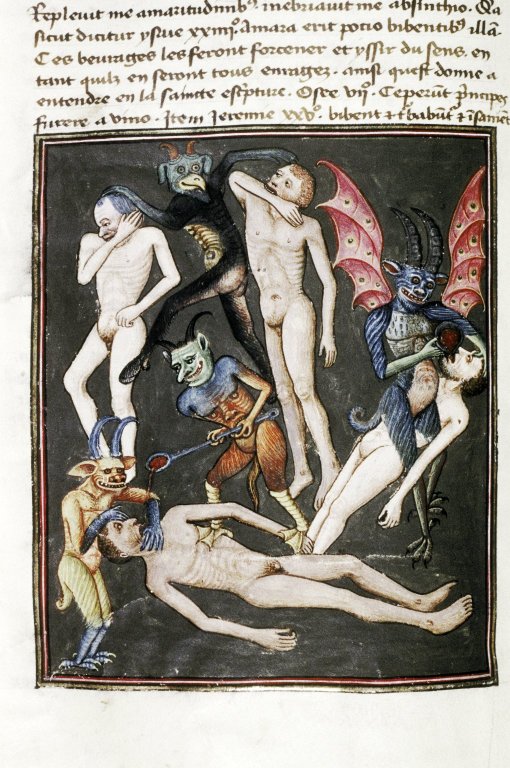

Having been cooked the damned are now ready for some appropriate punishment. Those guilty of the seven most terrible sins (at least in the Christian tradition), the so called ‘Seven Deadly Sins’, are punished in such a way that each punishment reflects in some way the nature of the sin.

Here the proud and vainglorious (i.e. those who think too much of themselves) are ‘broken’ on a terrible wheel. Standing tall and proud requires a strong back bone. No one will be doing much of that after this.

Here those guilty of Envy are being punished by immersion in either fire or ice, each no doubt thinking that the other lot have it easier!

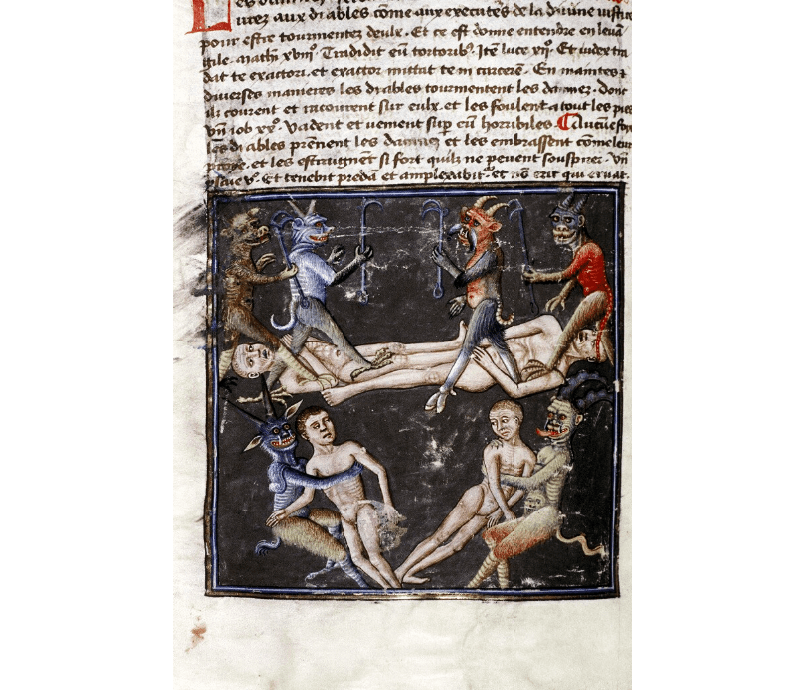

Here the wrathful (implaccably and violently aggressive) are being punished by experiencing the rage and aggression of the devils.

Below the slothful are being eaten by dragons and eagles. The wrathful and the slothful are close to each other for a reason. Sloth was considered to be closely connected to Wrath. Thomas Aquinas, reflecting on Aristotle’s distinctions between the different kinds of Wrath, the acute, the bitter and the difficult, wrote that “the bitter have a permanent Wrath on account of the permanence of the gloom they keep closed within them”. St. Bonaventure wrote “Wrath, when it cannot avenge itself, turns sullen, and thus from it is born Sloth”; and Brunetto Latini, Dante’s guardian and teacher, wrote that “In Wrath neglectful Sloth is born and abides,” Sloth was Wrath turned in on itself. These are not people who just don’t like hard work, these are people who bitterly resent having to do anything because they are angry all the time, an anger turned inwards in sullenness and gloom. Sounds like being a teenager to me!

Here are the avaricious being cooked. Interesting to see Popes, Bishops and Kings in there! People of this era were under no illusions about their rulers! O.K., here’s the interactive bit. What high profile political or religious figures would you like to see in your cauldron?!

Gluttony comes next in the list, a more henious sin than Lust which comes next. This interested me because in our modern church Lust is a much more high profile sin than Gluttony. Very few pastors or priests are thrown out of the church in disgrace for eating too much! But in the medieval era Gluttony was considered a worse sin than Lust because it was thought that for the glutton, food takes the place of God. It was in fact a form of idolatry. The classification of Gluttony as a greater evil than Lust is reflected in a widespread medieval interpretation of Genesis 2.15–17 and 3.6, according to which Adam’s sin was literally an excessive love of food! Since the food was offered to Adam by Eve, gluttony also had sexual implications and was seen (partly) as the root cause of Lust! So Lust and Gluttony were thought to be interconnected – the one (food) led to the other (sex)! Perhaps for that reason medieval spirituality emphasised fasting as a means to purge the soul!

Below the gluttons are being punished, but I am not sure I can explain how. It looks as if they are forced to sit around a meal table on which there is nothing palatable to eat.

And here are the lustful being cooked together. Just as they burned for one another while they were alive so they will burn with one another in this way in hell.

Anything else to confess?

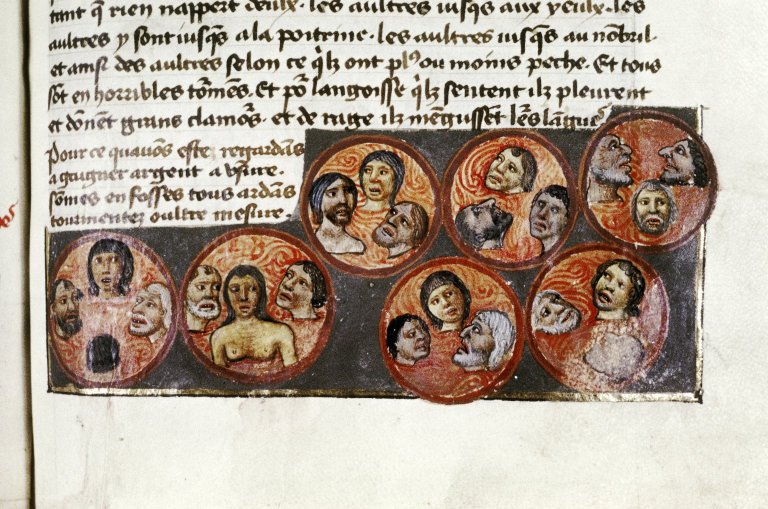

But of course there are many more than seven sins and the hell of Le Livre has something for everyone! Here the usurers (those who lend money for interest – bankers!) are being punished. They are immersed in wells of boiling water up to their deserved level.

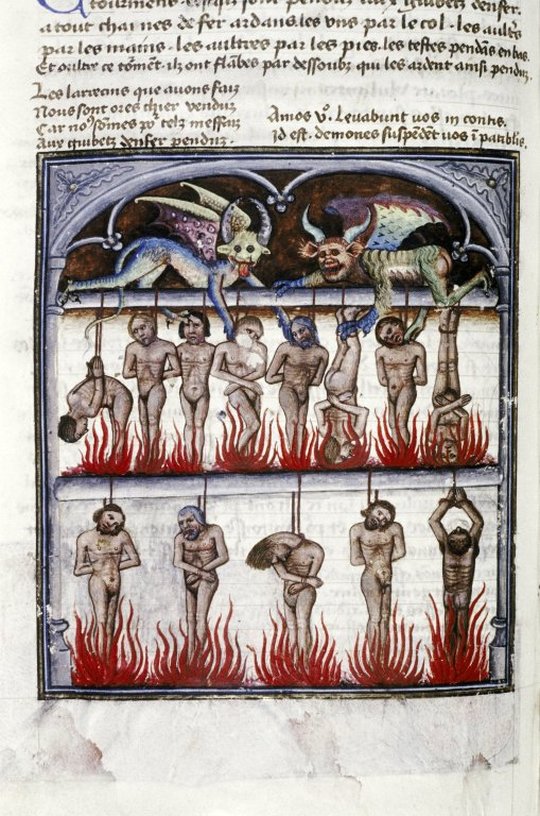

It was important to deter thieves. They are hung over flames while two delighted devils look at the reader.

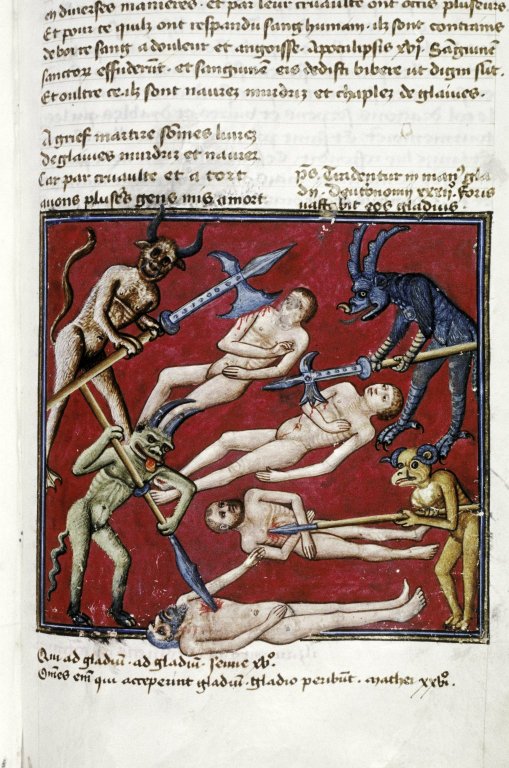

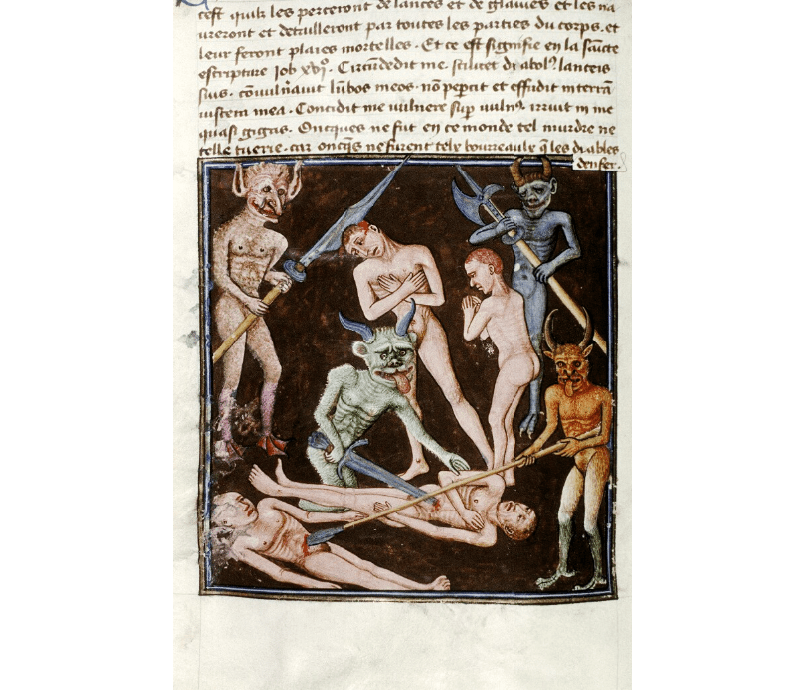

And murderers and tyrants get their comeuppance too. They experience violence and tyranny themselves.

Many rivers to cross

In Classical mythology the underworld was watered by at least four rivers and these are usually intergated into Christian accounts of hell. Here we see four rivers depicted. Below are the Styx and the Phlegeton.

According to some versions of Classical mythology the Styx was the river which the dead had to cross in order to enter the afterworld. The person (or being!) who ferried them across was called Charon. Some versions of the myth give the river a different name, the Acheron. Dante’s Inferno names both the Styx and the Acheron (so he ends up with five rivers only four of which are actually in hell). In Dante’s version of hell it is the Acheron that forms the border between the land of the living and hell and which the damned must cross (in Charon’s boat) to get to hell itself. The Styx is the second river Dante and Virgil find in hell. It begins life as a bubbling spring in the fourth level of hell and flows down into the fifth level where it forms a swamp in which the violent are punished. The name Styx in Greek meant ‘gloom’. In Le Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur it seems as if the Styx is a river the damned must swim over while being clubbed on the heads, not by Charon but by devils.

The Phlegeton was also a river taken from Classical mythology. The word in Greek means ‘fiery’. In Phaedo (112b) Plato describes it as “a stream of fire which coils around the earth and flows into the depths of Tartarus”. In Dante’s Commedia the Phlegeton in the third river of hell and it originates, like all the rivers of Dante’s Inferno, from tears flowing from a crack in the statue of the Old Man of Crete. Dante’s Phlegeton consists of boiling-hot blood, which probably symbolizes the blood of victims of violent death. The stream forms the first ring of the seventh circle, in which the sinners of violence against others are immersed at various depths corresponding to the severity of their crimes against their fellow men. Here in Le Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur it seems that is indeed a very hot and fiery river.

And here are the other two rivers of hell; the Lethe and the Cocytus.

In classical mythology the river Lethe represented forgetfulness. The waters of the river erased memory. In the Republic (10.621), Plato mentions Lethe as the river that the soul must drink during the process of metempsychosis, the passing of the soul at death into another body. In the Aeneid (6.713–715) Virgil refers to Lethe during Anchises’ speech on transmigration: only when the dead have had their memories erased by the Lethe that they may be reincarnated. According the Roman poet Statius the river Lethe borders Elysium, the final resting place of the virtuous in the underworld. This is how Dante conceives of the role of the Lethe and the river forms the physical boundary separating the pilgrim from the earthly paradise at the top of the mount of purgatory. The pilgrim must drink from the waters of the river to forget his sins before he crosses to paradise and begins his ascent to the highest heaven. Here in Le Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur it is found in hell.

The Cocytus, which means ‘the river of wailing’, is also associated in Classical mythology with the underworld. In some versions the Cocytus, along with the Acheron, forms the boundary of the underworld. In the Commedia Dante situates the Cocytus in the ninth circle of hell, right at the bottom, where its waters are frozen by the beating of Lucifer’s great leathery wings. In situating it here he was possibly influence by Isidore of Seville who in his Etymologies (book 14) located the Cocytus near Tartarus, the deepest, darkest part of hell. Here in Le Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur it seems very hot and fiery, not icy at all! But the monks’ conception of Satan is very different to that of Dante and hell isn’t arranged in every deepening circles. There is icy punishment but the river don’t freeze over.

And a terrible time was had by all

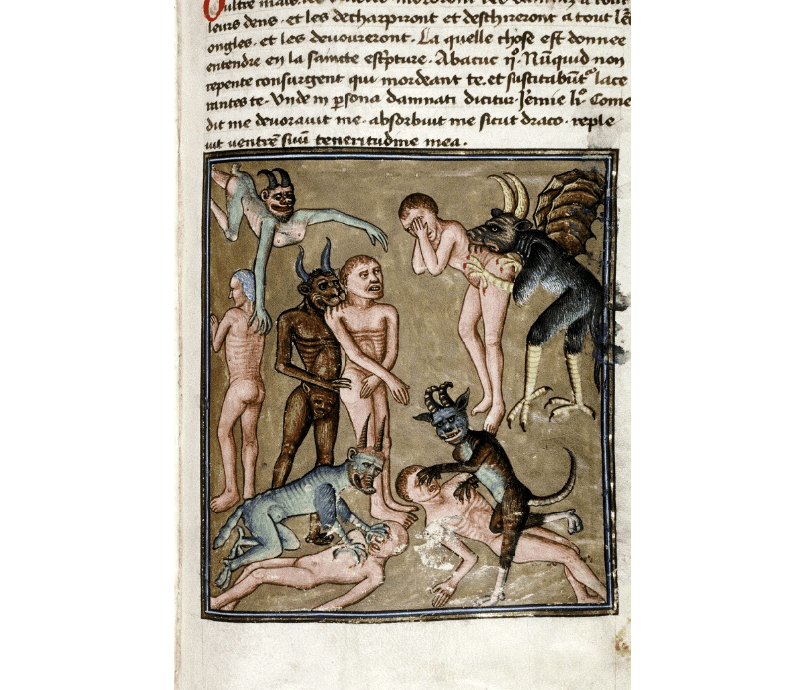

Finally (as far as this post is concerned) here are some images which were added I think, just to remind the reader that being in hell is a really, really bad way to spend your eternity. The interest (to me) is how the illustrator(s) identified the most painful and terrible forms of human suffering.

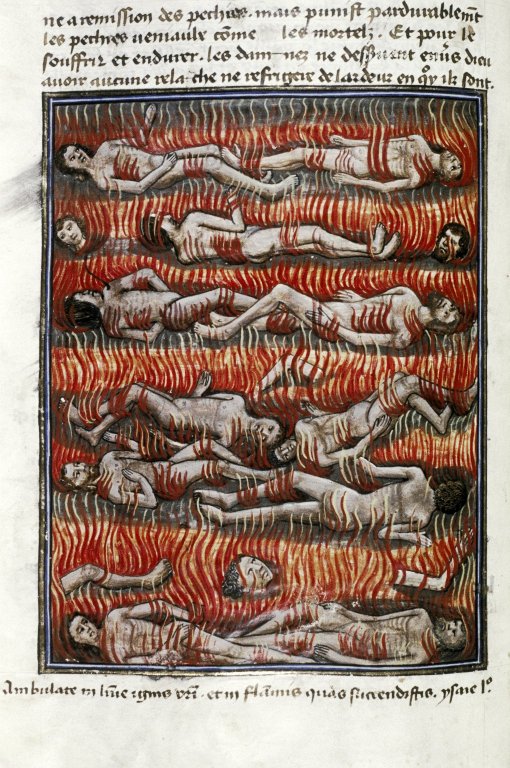

Too darned hot

Fire was generally the most popular image of eternal torment

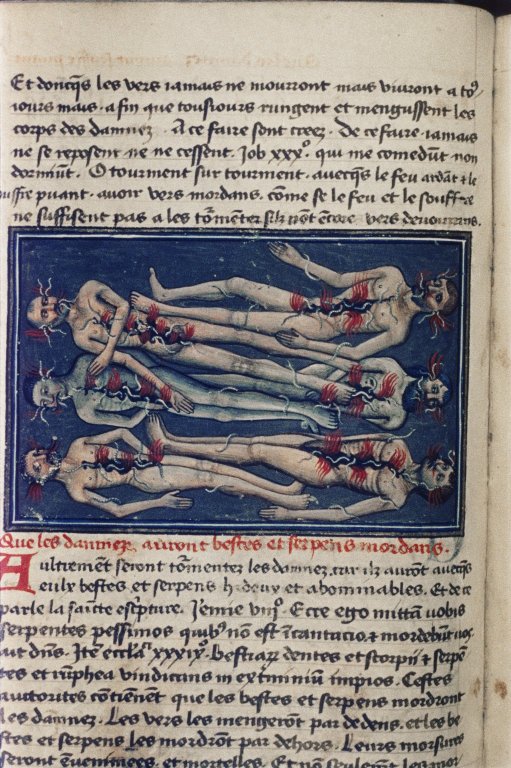

Being devoured

But being eaten seems to have been very popular too.

Here the damned are eaten by worms. The reference to worms is found in the bible (eg Mark 9.42-48) and becomes one of the main images of hellish torment in medieval art. The idea of having your body constantly gnawed away by little burrowing creatures is truly horrifying. Having spent a day in the mountain here in Sweden being eaten by thousands of mosquitos gave me some idea of how appalling this would be!

Here the damned are devoured by wild creatures and snakes.

‘You’re as cold as ice’

We usually think of hell as hot and fiery but in some depictions of hell freezing is an option too. Hell can be icily cold too. In Dante’s Inferno, sinners guilty of treachery are frozen in the waters of the Cocytus in the ninth circle of hell, The waters are frozen by the cold wind generated by the beating of Lucifer’s wings. The bottom circle of hell is a profoundly cold and silent place. This shouldn’t surprise us when we realise that God was usually thought of as pure light. People knew that the sun, the source of their light, was also the source of warmth and would readily have undeerstood the image of somewhere far away from God being dark and cold. The bottom of hell is as far away from God as you can get! Here we see the damned frozen.

Eat up!

And finally (for now) some poor souls being fed molten metal (or very hot tomato soup . . . not sure which – it’s hard to see)

These are amazing (and horrifying) images, intended to frighten people into believing in God and staying true to their religious vocations. It may also have provided some satisfaction to the readers to think of political and religious figures featuring in some of these hellish landscapes, being eaten, boiled, frozen and poked mercilessly. Surely we have all had such dreams!

- Dark Way to Paradise: Dante’s Inferno in Light of the Spiritual Path

Dante’s Inferno is often presented today in lurid ‘gothic’ terms as if it were no more than an entertaining demonic freak-show. Alternately, it is taken as merely a cultural and political commentary on Dante’s own place and time, cast in allegorical terms. But the Inferno, and the Divine Comedy as a whole, are much more than that. The human passions, and the Mystery of Iniquity of which they are expressions, are fundamentally the same in any place and time; the Inferno presents not so much a history of sin as a catalogue of the archetypes of sin, the fundamental ways in which all of us are tempted to betray the human form. Based on the works of a number of the Greek Fathers, on the writings of several members of the Traditionalist School, notably Frithjof Schuon and Rene Guenon, and on the kind of wide personal experience of the violation of the human form that is available to anyone in these times with both the requisite discernment-rooted in love-and the courage to keep his or her eyes open, Jennifer Doane Upton has once again seen Dante’s Inferno as it really is. It is the record of the struggle of the human mind, will, and emotions to discover and name, by the grace of God, the sins resident in the human soul. As both a traditional re-presentation and a contemporary revisioning of the ‘examination of conscience’, individual and collective, Dark Way to Paradise is at once an exegetical masterpiece and a handbook of demonology of concrete use to any true physician of the soul. In its direct application of metaphysical principles to ‘infernal psychology’, it is unique among Dante commentaries. And in a time like ours, when the Western Church appears to be dissolving before our eyes, to save again what Dante himself saved out of the great medieval Christian synthesis has never been so timely.

- The Ordeal of Mercy: Dante’s Purgatorio in Light of the Spiritual Path/The vertical path

The Ordeal of Mercy is a book of wide erudition and simple style; its goal is to present the Purgatorio, according to the science of spiritual psychology, as a practical guide to travelers on the Spiritual Path. The author draws upon many sources: the Greek Fathers, notably Maximos the Confessor; St. John Climacus; Fathers and Doctors of the Latin Church, including St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas; John Donne, William Blake and other metaphysical poets; the doctrines of Dante’s own initiatory lineage, the Fedeli d’Amore; the modern Eastern Orthodox writers Pavel Florensky and Jean-Claude Larchet; and the writings of the Traditionalist/Perennialist School, including René Guénon, Frithjof Schuon, Martin Lings, Leo Schaya, and Titus Burckhardt.

Other exegetes of Dante have dealt with the overall architecture of the Divine Comedy, its astronomical and numerical symbolism, its philosophical underpinnings, and its historical context. Jennifer Doane Upton, however–while preserving the narrative flow of the Purgatorio and making many cogent observations about its metaphysics–directs our attention instead to many of its “minute particulars,” unveiling their depth and symbolic resonance. She presents the ascent of the Mountain of Purgatory as a series of timeless steps, each of which must be plumbed to its depths before the next step arrives; in doing so she demonstrates how the center of this journey of purgation is everywhere, and its circumference nowhere.

In the words of the author, “The soul in its journey must divest itself of extraneous tendencies and desires in order to become the ‘simple’ soul of theology–the soul of one essence, of one will, of one mind. If it can do this it will reach Paradise, its true homeland.”

“The Ordeal of Mercy is the finest commentary on Dante’s Puragtorio that I have ever read, an indispensable book for all those who want to understand the paradoxical dance of grace on the path to liberation.”–Andrew Harvey, author of The Hope: A Guide to Sacred Activism

“The Ordeal of Mercy presents a detailed and erudite metaphysical commentary on the Cantos of the Purgatorio section of Dante Alighieri’s ‘Fifth Gospel,’ La Divina Commedia, one that is clearly the fruit of extensive research combined with deep contemplation. Dante himself said that his poem had an interior sense beyond the surface meaning; Jennifer Doane Upton’s approach accordingly opens the Cantos of Purgatorio–whether we take it as an account of purgation in the post-mortem realms or as the passage through this present life understood as an ‘ordeal of mercy’–to the eye of initiatic apprehension, the eye of the Heart. Seemingly minor motifs are homed in on to reveal their deep significance, as well as their place in the broader pattern of the Purgatorio, which corresponds to the stage of Purgation on the Christian Way.”–Nigel Jackson, More Info on website of Charles Upton

Look also Because Dante is Right