Ethiopian Christmas is celebrated on 7 January (Tahsas 29 in the Ethiopian calendar) as the day of Jesus’ birth, alongside the Russian, Greek, Eritrean and Serbian Orthodox Churches. It is also celebrated by Protestant and Catholic denominations in the country.

Ethiopian Orthodox Christians are expected to fast for 43 days, a period known as Tsome Nebiyat or the Fast of the Prophets. Fasting also includes abstaining from all animal products and psychoactive substances, including meat and alcohol. Starting on 25 November, the fast believed to be “cleansing the body of sin” as they await the birth of Jesus.

Nativity Fast

Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Churches commence the season on November 24 and end the season on the day of Ethiopian Christmas, which falls on January 7. The corresponding Western season of preparation for Christmas, which also has been called the Nativity Fast[2] and St. Martin’s Lent, has taken the name of Advent. The Eastern fast runs for 40 days instead of four (in the Roman Rite) or six weeks (Ambrosian Rite) and thematically focuses on proclamation and glorification of the Incarnation of God, whereas the Western Advent focuses on three comings (or advents) of Jesus Christ: his birth, reception of his grace by the faithful, and his Second Coming or Parousia.

The Byzantine fast is observed from November 15 to December 24, inclusively. These dates apply to the Eastern Catholic Churches, and Eastern Orthodox churches which use the Revised Julian calendar, which currently matches the Gregorian calendar.

It is also known as the Feast of Theophany, a cornerstone in Orthodox Christianity. It’s a time when the air buzzes with anticipation, as believers prepare to commemorate a pivotal moment in Christian faith: the baptism of Jesus Christ.

The Significance of Theophany in Orthodox Christianity

This feast is far more than a mere commemoration; it’s a celebration of Jesus Christ’s baptism in the Jordan River. This event marks the manifestation of God as the Holy Trinity to the world — Father, Son, and Holy Spirit — providing a profound revelation of Divine truth that resonates with believers.

Theophany stands as a pivotal point where heaven meets earth. During the liturgical services, especially through the Great Blessing of the Waters. This ritual is not only about purification but also signifies the sanctification of the entire creation. Orthodox theology teaches that when the waters are blessed, they become a means of spiritual renewal, symbolizing the washing away of sins.

Indeed, every aspect of Theophany is imbued with deep symbolism which adherents internalize and reflect upon. The icons depicting the feast portray the voice of God the Father proclaiming Jesus as His beloved Son, the Holy Spirit descending as a dove, and the figures of angels in awe. These are not just static images but invitations for us to contemplate the mystery of God becoming manifest in the world.

Orthodox Christians believe that participating in Theophany services invokes a renewal of their own baptismal vows. The prayers and hymns are designed to draw us closer to the heart of our faith, a personal call to embrace the transformative teachings of the gospel. It’s during Theophany that we reaffirm our commitment to live a life in accordance with Christ’s example.

By observing Theophany, we are reminded of the unity between the cosmic and the personal elements of faith. The feast illustrates that salvation history is not confined to the past but is an ongoing narrative that continues within the life of every believer. Through this understanding, we grasp the scope of God’s redemptive work, which is both intimate and universal.

The Roots of Theophany in Christian Tradition

The history of Theophany stretches back to the earliest days of Christianity. In the Christian tradition, the feast commemorates not only Christ’s baptism but also His first public manifestation to the world. Theophany’s origins are tightly interwoven with the liturgical traditions that emerged in the early Church.

Liturgical records from as early as the 4th century detail the observance of the feast, illustrating its ancient roots and enduring importance. It was considered a major feast, sometimes even correlated with the celebration of Easter, accentuating its significance in the context of Christian redemptive events.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, Theophany is often referred to as ‘Epiphany,’ a term that signifies a divine revelation. The feast is deeply rooted in the scriptural accounts of the Gospels, particularly in the works of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. These texts detail the event of Jesus’s baptism by John the Baptist at the Jordan River, marking it as an occasion where the Heavens opened and the Holy Spirit descended like a dove upon Jesus, while a voice from Heaven proclaimed Him as the beloved Son.

Celebrated on January 6th, this feast not only observes the baptism but also Christ’s first miracle at the wedding of Cana, which occurs shortly thereafter according to the Gospel of John. This dual focus on baptism and miracle underscores the multifaceted nature of divine manifestation and the profound mystery of God’s presence.

Orthodox Christians recognize this event as a cornerstone of their faith, as it reveals the Trinity — Father, Son, and Holy Spirit — to the world, and establishes the foundation for the sacrament of baptism. By looking at the roots of Theophany and its establishment in the early Christian Church, one gains a deeper appreciation for its central place in Orthodox ritual and doctrine. It continues to resonate through centuries as a powerful expression of faith, an acknowledgement of the divine mystery, and a call to a life transformed by the recognition of Jesus Christ’s divinity.

The Baptism of Jesus Christ: A Pivotal Moment

In the rich tapestry of Orthodox Christianity, the Feast of Theophany stands out, particularly for its commemoration of the baptism of Jesus Christ. This moment in the Jordan River signifies far more than a mere ritual. It marks the beginning of Christ’s public ministry and the divine approval of his mission on Earth. When I reflect upon this event, I’m moved by its profound significance, encapsulated in the voice from heaven declaring Jesus as the beloved Son.

Scripture recounts this pivotal moment with poignant clarity. As Saint John the Baptist lowers Jesus into the waters, the heavens open, and the Holy Spirit descends like a dove — a scene capturing the full revelation of God’s triune nature.

Beyond its doctrinal import, the baptism also symbolizes a model for personal transformation. In Orthodox tradition, followers re-commit to spiritual renewal, mirroring the purifying act that Jesus himself underwent. This moment beckons the faithful to embody Christ’s virtues and fosters a profound connection to his journey.

Moreover, the baptism induces a ripple effect throughout the liturgical year. It’s not merely an isolated event but a gateway to the subsequent narratives of Christ’s life and teachings. Each year, we are reminded of the seasons that follow — each echoing the resonant themes introduced by the baptism.

As the story of the baptism unfolds, the multifaceted themes interwoven in the Theophany celebration emerge starkly. Through liturgy and iconography, the Orthodox Church encapsulates the transformative power of water, the inauguration of Christ’s ministry, and a life led by example. These threads bind the observance, not only to the past but also to our contemporary journey in faith. The baptism of Jesus Christ remains an enduring call to renew and deepen our spiritual lives in alignment with the core precepts of Orthodoxy.

The Symbolism of Water in Theophany

Water plays a central role in Theophany, symbolizing purity, life, and transformation. It’s perceived not only as a physical substance but also as a spiritual one, carrying profound connotations within Orthodox Christianity. During Theophany, water is blessed and believed to take on holy properties, becoming a conduit for sanctification and an emblem of divine grace.

As I delve into the scriptures, it’s clear that water carries a duality of destruction and regeneration. In the Old Testament, it is seen in the great flood that cleanses the world of sin, and in the New Testament, it appears as the waters of the Jordan River where Jesus was baptized. This baptismal water signifies a new beginning, washing away the old self and refreshing the spirit akin to the rebirth of Creation after the deluge.

The practice of blessing bodies of water during Theophany also holds symbolic weight. Orthodox Christians often gather at rivers, lakes, or seas, where the blessing is performed. This ritual signifies the sanctification of nature and is a reminder of the participation of all creation in the redeeming act of Christ’s baptism.

Moreover, theophany water is used throughout the year for various sanctifying purposes, reinforcing its significance far beyond the feast day:

- Blessing homes

- Healing purposes

- During other sacraments and rituals

In baptism, the symbolism of water reaches its zenith. It represents a tomb and a womb simultaneously — a tomb for dying to sin and a womb for giving birth to new life in Christ. Orthodox faithful view their own baptism as a personal participation in Jesus’ baptism. They’re reminded that through the waters, they’re initiated into the faith, emerging as changed individuals ready to embark on their spiritual journey.

In the liturgy, the use of water serves as a material and mystical link between the physical and the divine. The blessing of the waters during Theophany is a vivid enactment of divine incarnation and sanctification, encapsulating the essence of God’s closeness and the transformative power of His presence in the world.

The Sacred Rituals of Theophany

Theophany isn’t just a day for reflection; it’s marked by a rich tapestry of sacred rituals that engage the faithful in a profound spiritual journey. Among these, the Great Blessing of the Waters stands out as a pivotal moment. This ceremony is performed twice: once on the eve and then on the day of Theophany itself. During this ritual, the priest proceed to sprinkle holy water, a sign of divine presence, on the congregation, symbolizing the washing away of sins.

In many Orthodox communities, there’s a tradition of throwing a cross into a body of water. The bravest among the faithful dive in — regardless of the chilling temperatures — to retrieve it. This act of retrieving the cross signifies Christ’s baptism and serves as a public declaration of faith.

I’m also intrigued by house blessings, a practice where the sanctified waters from Theophany are used to bless and protect the homes of parishioners. A priest typically visits homes with a container of Theophany water, sprinkling each room while reciting prayers. This custom underlines the belief that God’s grace permeates every aspect of our lives.

These rituals aren’t simple ceremonies; they’re acts that bind the community together. They root Orthodox Christians in their faith, allowing them to participate physically in the mysteries of Theophany. Each droplet of water becomes a symbol of the Holy Spirit’s renewing power — connecting the earthly with the heavenly.

Clearly, Theophany’s rich liturgy and communal practices go beyond mere remembrance. They’re about engaging with faith at the deepest levels, where holy water isn’t just a symbol — it’s a living, breathing testament to belief, renewal, and the enduring promise of sanctification.

Conclusion

The Feast of Theophany holds a profound place in Orthodox Christianity, not just as a historical commemoration but as a living, communal experience. Through the Great Blessing of the Waters and other cherished rituals,we are reminded of the depth of our faith and the transformative power of God’s presence. As the holy water touches our lives, we’re renewed and united in the divine mystery. Theophany isn’t simply an event to remember — it’s an invitation to step into a renewed life, a moment where heaven touches earth and sanctifies our journey.

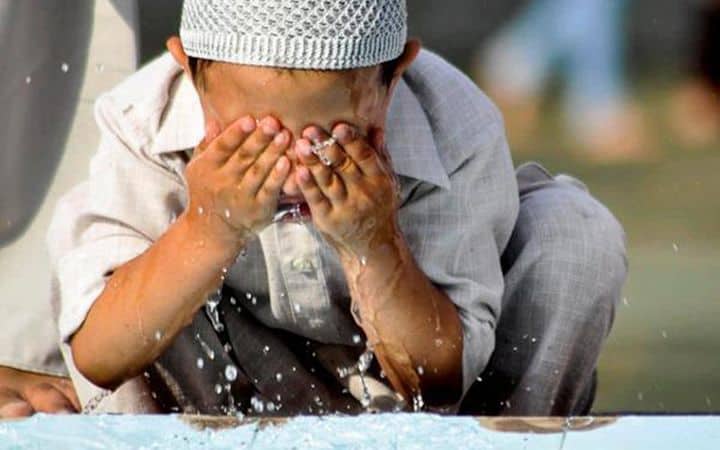

Note:Ablution – ritual of Purity in Islam

Wuduʾ (Arabic: الوضوء, romanized: al-wuḍūʼ, lit. ‘ablution’ [wuˈdˤuːʔ] ⓘ) is the Islamic procedure for cleansing parts of the body, a type of ritual purification, or ablution. The steps of wudu are washing the hands, rinsing the mouth and nose, washing the face, then the forearms, then wiping the head, the ears, then washing or wiping the feet, while doing them in order without any big breaks between them.

Wudu is an important part of ritual purity in Islam that is governed by fiqh,[1] which specifies hygienical jurisprudence and defines the rituals that constitute it. Ritual purity is called tahara.

Wudu is typically performed before Salah or reading the Quran.

Wudu is often translated as “partial ablution”, as opposed to ghusl, which translates to “full ablution”, where the whole body is washed. An alternative to wudu is tayammum or “dry ablution“, which uses clean sand in place of water due to complete water scarcity or if one is suffering from moisture-induced skin inflammation or illness or other harmful effects on the person.

Qur’an 2:222 says “For God loves those who turn to Him constantly and He loves those who keep themselves pure and clean.”[2:222]

Qur’an 5:6 says “O believers! When you rise up for prayer, wash your faces and your hands up to the elbows, wipe your heads, and wash your feet up to the ankles. And if you are in a state of full impurity, then take a full bath. But if you are ill, on a journey, or have relieved yourselves, or have been intimate with your wives and cannot find water, then purify yourselves with clean earth by wiping your faces and hands. It is not Allah’s Will to burden you, but to purify you and complete His favor upon you, so perhaps you will be grateful.”

The Blessing Of The Waters – A Perennial New Beginning

- Each year at Theophany we perform the service of the Great blessing of the waters. With this holy water or Agiasmos, as we call it, the priest blesses the people and their homes in a “pilgrimage” through their homes lasting sometimes more than a month. For the modern person that, has lost any sense of the sacred under the influence of the protestant theology and the secular society, all this seems a rather odd habit to say at least.

But even for the secular man the water has tremendous importance. According to the evolution theory life has started in the water. It is also an essential component of the life cycle, without it nothing can grow or live. Man himself is made 50-65% from water and although one can survive weeks without food, without this essential liquid man surely dies in a matter of days.

So how do we respond to the raised eyebrow of the secular man when we bring the Holy Water into discussion?

The first and obvious answer lays the very meaning of Theophany that incorporates the Baptism of our Lord Jesus Christ in the River Jordan. The entrance of the Lord Himself into the water and all the events that followed, the flowing back of the river and the revelation of the Holy Trinity should be for us a good enough explanation.

But there is more to add because this is not the first time when water plays a central role in the Holy Scripture. Since the beginning of times water was used by God in various occasions. At the very creation of the world we read that “the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.” (Gen 1:2). We remember the Great Flood that prevailed upon the earth drowning a mankind that was already sinking into un-repented sin. We see Moses parting the Red see with his staff so the people of Israel can be freed from the slavery of the Egyptian Pharaoh, while the pagan armies are destroyed by the same waters. We also acknowledge water as part of the purification rituals of the Mosaic Law.

The complete meaning of the importance of the water however is fully revealed in the water of Baptism. The key is the hymn we sing as we joyfully walk around the table with the Gospel at the end of the service: As many of you have been baptized in Christ you have put on Christ. As we are baptized in the water by a thrice immersion in the name of the Holy Trinity, we become Christ like. By dying as sinners in the water like in a tomb – three times, like three days – we are able thereafter to rise like Christ into incorruption, as members of the Church now and citizens in potentiality of the Kingdom of Heaven. Christ the New Adam, through the water of Baptism, is re-creating us in the Spirit, giving us again the choice that our forefathers failed so lamentably: a life in grace or a life in sin.

We recognize here the creation power of Genesis, the wrath of the Lord during the Flood and the liberating power of the Red Sea commanded by the wood of the Cross.

“Creation, Fall and Redemption, Life and Death, Resurrection and Life Eternal: all the essential dimensions, the entire content of the Christian faith, are thus united and hold together”

Through the descent of the Holy Spirit during Baptism and in the similar way during the Great Blessing of the Waters, the water regains its full potential and is transformed in a vehicle of renewal, a vehicle of change leading everything it touches toward the meeting with our Lord Jesus Christ.

This is possible because the Sacrament of Baptism is not to be understood as separated from Communion and Holy Liturgy, although the current liturgical practice does not really help in this respect, but the two should be considered as they really are: intimately linked. As Fr. Alexander Schmemann accurately states:

“Baptism is a personal Pascha and a personal Pentecost, as the integration into the laos, the people of God, as a passage from an old life into a new one and finally as an epiphany of the Kingdom of God.”

The Holy Communion is the earnest of the very goal of the Christian life: the Kingdom of Heaven. Each person that enters through baptism into the body of the Church starts living for the fulfillment of this promise, which is pre-tasted during the Holy Liturgy in the partaking of the Eucharist. The water of baptism makes all of this to happen by giving back to man his original potential.

Each year at Theophany we take part again and again in the reactivation of the spiritual properties of water by witnessing the river Jordan running backwards to its source, to its origins, symbolically reverting our lives to our true sacred roots. The Agiasmos consecrated at Theophany has the power to take us back were we belong, to renew into us the true Spirit of God and, paradoxically, instead of extinguishing, fueling the flame of our faith.

This Holy Water however does not work magically without our participation, but it demands involvement and requires a renewal of our dedication to Christ and His Church. It is for us a remembrance and a reaffirmation of our baptismal vows, it is a perennial new beginning that we embark in every time we use it. Without this understanding the sprinkling of Agiasmos is nothing else but an unwanted cold shower, devoid of any true significance.

Let us therefore receive the water of Baptism in our homes in the hope that the New Year will bring us closer to Christ and to one another. Let us all pray that the Holy Spirit that fills all things will also fill our lives with His peace and grace and that at the end of our lives we will be found worthy to join the rightful flock at the right hand of the Father.

Three Kings Day

Epiphany , Epiphany or Epiphany of the Lord ( Solemnitas Epiphaniae Domini in Latin ) is a Christian holiday celebrated annually on January 6 ( or on the first Sunday after January 1 – see below ) commemorating the Biblical event ( Matt. 2:1-18) of the wise men from the East who saw a rising star and went out to seek the King of the Jews. They arrived in Bethlehem and found Jesus , the newborn King of the Jews. This probably alludes to the vision of Balaam, the seer in Moab who saw a star rising out of Jacob ( Numbers 24:17).

The three wise men were given names. In Greek they were Apellius, Amerius and Damascus, in Hebrew Galgalat, Malgalat and Sarathin, but they became known by their Latinized Persian names Caspar , Melchior and Balthasar . They are said to have been 20, 40 and 60 years old respectively, numbers symbolizing the life periods of the adult.

In the Catholic liturgy in Belgium and the Netherlands, the feast of the Epiphany of the Lord is celebrated on the first Sunday after January 1. In many southern European countries, Epiphany is a holiday and Epiphany is celebrated on the day itself. The Epiphany of the Lord is the first of three feasts, together with the Baptism of the Lord and the Presentation of the Lord in the Temple ( February 2 ), that belong to the Christmas cycle , the time of Jesus’ childhood and youth.

Read more here: Three Kings: Uses in different countries

example :The Netherlands

In some parts of the Netherlands, children walk in groups of three dressed up with a crown along the doors on the evening before Epiphany; one of them has a blackened face. They carry lanterns and sing. A well-known song goes:

Three cooonings, three cooonings,give me a new (h)ood.My old one is worn out,my mother may not eat it again.My father has the money,counted down on the counter.

Originally the last sentence read: “counted on the [russel] grid.” Counting on the grid here means: not having money or not being able to keep track of it. [ 6 ] This version is still sung in Flanders.

The last two lines also read: “My father has no money, isn’t that a bad situation?”

As a reward for singing, they receive food, sweets and money . The lanterns are a remnant of an old pagan custom, in which torches were carried to drive away evil spirits. The sweets that are handed out originate from pagan sacrificial meals. The Germans were not allowed to eat legumes (their staple food) during the twelve nights of the New Year’s festivities and the ‘holy bean’ marked the end of that fasting period.

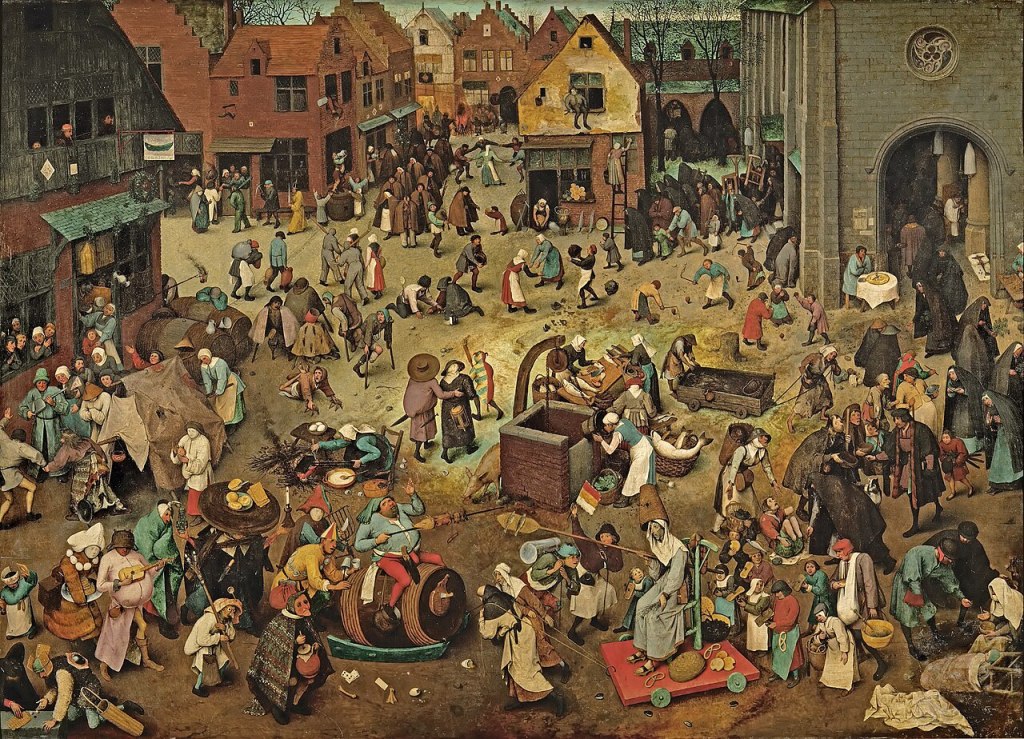

In the house, Epiphany was celebrated with food, drink and song. Jan Steen depicted this in the painting The Feast of the Three Kings .

The king’s bread or king’s cake that is baked is well-known; a brown bean or coin is hidden in it and the person who finds it is “king(in)” that day. A custom is that the person who is the king may be the boss in the house that day. The bean in the cake is also derived from pagan customs.

The king’s letter was also known , both in the home and at a large official party. One could grab from a barrel of papers and the one who drew the king’s letter was treated by everyone and was the boss. Letters were also drawn for the position of councillor, steward, secretary, singer, musician, cook, porter, cupbearer and fool and foolish woman. According to a legend, King Francis I of France heard about such a king’s letter for the first time in 1521, he declared war on the ‘king’ and went there, but was received with snowballs , apples and eggs . A drunken man even threw a piece of burning wood , but King Francis saw how foolish he had made a fool of himself and refused to prosecute the man.

In the past, it was common practice to leave the Christmas tree up until Epiphany. According to tradition, taking down the tree before Epiphany would bring bad luck. Nowadays, however, most Christmas trees are taken down before Epiphany. [ 7 ] In the past, it was also common practice not to put the Epiphany figures in the nativity scene right away, but only on January 6, at Epiphany. The figures were moved a step closer to the nativity scene every day, because they were still ‘on their way’ and would not reach the scene until January 6. [ 8 ] [ 9 ]

At churches or in the church porch a play was performed around Epiphany with Mary , Joseph , the baby Jesus , the donkey , the ox , Herod and the Three Wise Men. In Protestant areas this also happened inside the church.

In Maastricht (organised by the parish of Our Lady Star of the Sea ) and ‘s-Hertogenbosch (by the ‘s-Hertogenbosch Three Kings Foundation), live Three Kings processions pass through the city centre every year. Fully costumed, the kings ride through the city on camels and horses. The procession also includes shepherds with donkeys and sheep and of course Mary and Joseph with the baby Jesus. Children (whether or not in costume) are invited to walk along with lanterns. The service concludes in the basilica, during which the Kings offer their gifts to the baby Jesus and traditional Three Kings songs are sung. In ‘s-Hertogenbosch, a new tradition was added in 2015: the fourth gift. Children could bring toys that still looked new, to be collected in St. John’s Cathedral and donated to children who were less fortunate.

In Enkhuizen, among other places, the Three Kings Star was known. A fragile object made of paper and wood that was carried along the houses on Epiphany. With the star on the stick, the bearer sang a song and collected small amounts. The Zuiderzee Museum has recordings of songs, eyewitness accounts, photos of the owner in action and two stars, one of which has been restored to its former glory.

In the 21st century, the tradition of Epiphany is considered lost in the Netherlands. [ 10 ] However, the tradition still lives on in Maastricht, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Tilburg and Lierop. In 2012, the Brabant Epiphany singing was added to the Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Netherlands . [ 11 ] In addition, the Heemkundekring Tilborch is committed to keeping the festival alive. According to Ineke Strouken, director of the Dutch Centre for Folk Culture, about Epiphany as intangible heritage: ‘It is dynamic heritage that must be given space to grow with the times and acquire new meanings.’

See also 14 january: The Feast of the Ass