for Paul

The Resolution of Opposites & the Will of Heaven

This study ( an hermeneutic exploration of Rene Guenon) examines how the architecture of the various sacred traditions, all manifest in their built expressions a universal symbolic content, while at the same time being absolutely unique in their own inherent particular spiritual dispensation.

One major aspect of this symbolic content is the embedding of the three-dimensional cross in its various modes within their built arrangements. The correlation between the three dimensions of space and the metaphysical symbolism of the cross was the subject of a short but important work by the French traditional metaphysician Rene Guenon titled Symbolism of the Cross (Le Symbolisme de Ia Croix).

In describing the purpose of the work Guenon wrote that it was ‘to explain a symbol that is common to almost all traditions, a fact that would seem to indicate its direct attachment to the great primordial tradition’.

While several authors on sacred architecture acknowledge the importance of Guenon’s work, it has generally been applied only in limited considerations and to particular traditions. However, there remains many levels to this work that require further general elaboration and exploration. Guenon uses the symbolic potential of three-dimensional space as a coherent and indispensable means of developing traditional metaphysics. An hermeneutic exploration and study of Guenon’s Symbolism of the Cross, allows insights into various aspects of all sacred architecture, even when the tradition is unfamiliar. Equally, exploring various themes related to spatial symbolism in sacred architecture can give insights into the interpretative reading of Symbolism of the Cross.

- The Cycles of the Sun

The resolution of complementary and opposite dualities is a major theme of Symbolism of the Cross. While the Sun as a symbol of Being, its motion is perhaps the clearest example of these dualities. What follows is an examination of the Sun’s apparent movements and its symbolic characteristics, as well as other celestial motions, and how this resolution follows the traditional notion of the ‘Will of Heaven’.

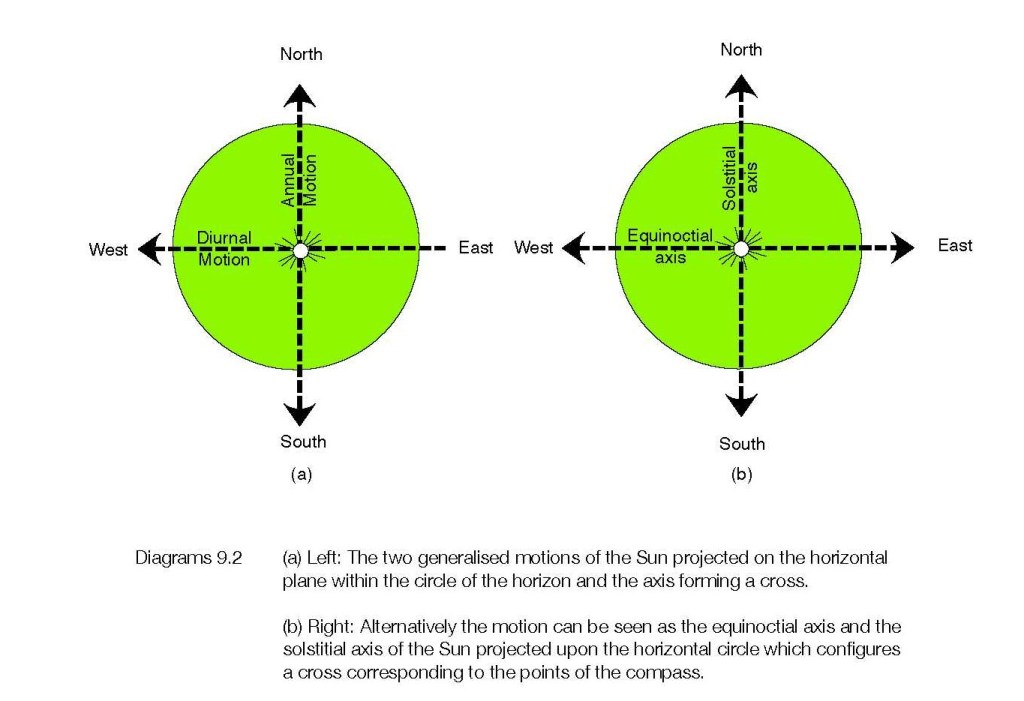

The first and most obvious motion of the Sun is its daily rising in the East and setting in the West (Diagram 9.1(a)). This motion has four nodes: sunrise, midday and sunset and the inferred but invisible node of midnight. These nodes form a spatial and temporal cross superimposed on the Sun’s circular path. The second motion is annual, demonstrated by the Sun’s rise to a maximum angular elevation at midday in Summer followed by a minimum angular elevation in Winter (Diagram 9.1(b)). This change in angular elevation occurs on a meridian that is due North in the Southern Hemisphere and due South in the Northern Hemisphere. This meridian is the first naturally determinable direction caused by the seasonal displacement of the Sun. The seasonal motion of the Sun for areas outside the tropics occurs between the zenith of the visible hemisphere of the sky and the North for the Southern Hemisphere and the zenith and the South for the Northern Hemisphere. For those areas within the tropics, the motion is entirely North and South of the zenith. The position of the Sun’s rising and setting points on the horizon move correspondingly. These angles change according to the latitude of the place considered and constitute the azimuth of the Sun’s annual movement in the horizontal plane.

- T h e S o l s t i t i a l & E q u i n o c t i a l Cross

Just as the Sun’s diurnal cycle is divided into temporal quarters, so too is the annual cycle. This division of the annual cycle is determined by the highest and lowest meridian crossings of the Sun, when the days at each extreme of the cycle are respectively the longest (mid-summer) and shortest (mid-winter) days of the year. Between these two extremes lie the median points when the days and nights last 12 hours each. Thus the four annual time divisions reflect the four diurnal time divisions (Diagram 9.2(a)). Midday reflects the summer solstice, midnight reflects the winter solstice and sunrise and sunset reflect the spring and autumn equinoxes. The diurnal and annual motions of the Sun are thus homologous with the division of space and time into quarters, which can be summarised graphically as the spatial cross. The East-West axis symbolises the equinoctial axis of the Sun, which is the result of its rising in the East and setting in the West, and this axis corresponds to the horizontal or passive arm of the cross. The North-South axis corresponds to the motion of the Sun as it travels between the extremes of the winter and summer solstices and corresponds to the active, vertical arm of the cross (Diagram 9.2(b)).

The cross of the equinoctial axis and solstitial axis configure a pair of what Guénon terms ‘complementary opposites’. This symbolic relation between the Sun’s annual motion and the points of the compass can be expanded into a complex array of symbolism. (In the I Ching it is stated: ‘Thus men divide the uniform flow of time into the seasons, according to the succession of natural phenomenon, and mark off infinite space by the points of the compass. In this way nature in its overwhelming profusion of phenomenon is bounded and controlled.’ T’ai (Peace) Hexagram No. 11)

This is particularly significant in the Chinese and Indian traditions but finds application in other traditions as well. In the Hindu tradition it is the motion of the sun that ‘paces out’ the quartering of space and time and is mythologised as the three steps of Vishnu who in order to achieve the prized unity with the sun, strode across the three worlds emulating the Sun on its daily journey. The important consideration relevant to this study however is that the Sun alone is responsible for the quaternary divisions of space and of time. It is the Sun that quarters first time and then by implication the undifferentiated directions of space, bringing structure to the corporeal domain. The crossing of the equinoctial with the solstitial axis is an important configuration of the cross and is often incorporated into sacred architecture and will soon be developed.

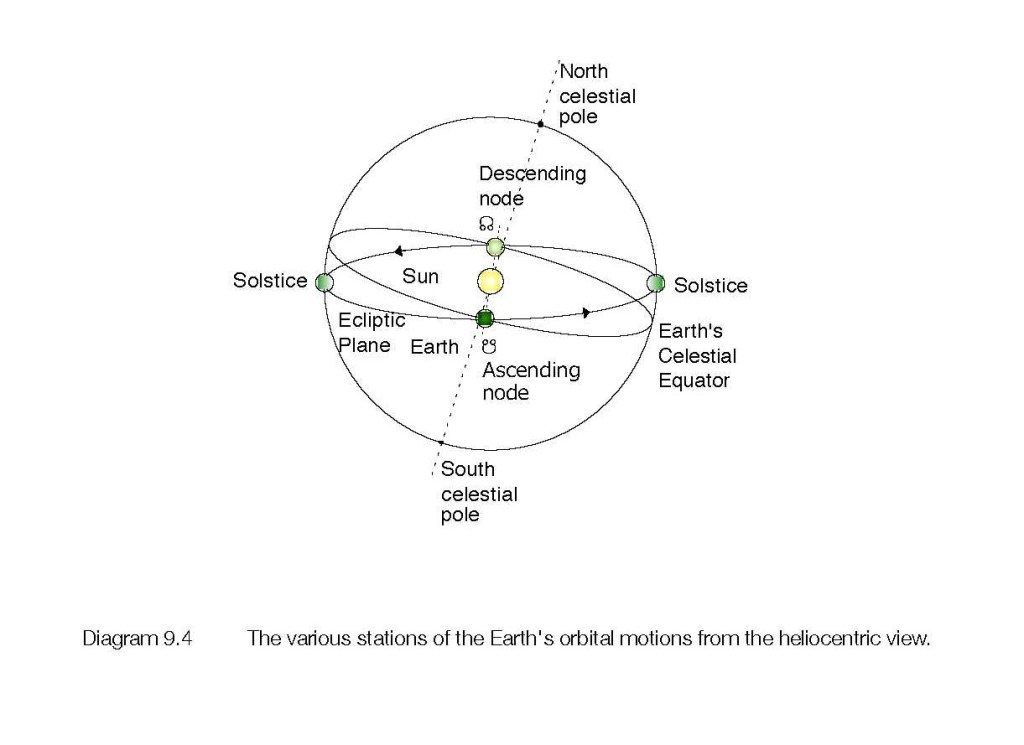

The celestial vault or sphere which forms the backdrop of the sky from the perspective of the Earth has projected upon it what is known as the celestial equator. This band or belt is a celestial ‘great circle’ which is the projection of the equator onto the outer sphere of the sky. Although theoretically a geometric projection, this belt or band is real and the locus of the greatest stellar movements in the night sky. It lies at exactly 90° from the celestial pole, which is the projection of the North and South Poles on the celestial sphere. The significance of the celestial equator is not evident during the day, when the brilliance of the Sun diminishes everything else, but at night its theoretical projection becomes apparent. However, the passage of the Sun across the sky coincides with the celestial equator only at the equinoxes. From a geocentric view, the Sun’s passage relative to the (unseen) starry vault is the ecliptic plane and inclines at 23° 27′ (termed the ‘obliquity of the ecliptic’) to the equatorial plane. This is not apparent during the day but the Sun’s position relative to the stars and the celestial sphere can be determined just before sunrise and just after sunset. From a heliocentric view, the ecliptic plane is the plane of the Earth’s rotation around the Sun (Diagram 9.3(a) & (b)).

When these two planes, or ‘great circles’, are considered from either perspective, two points are significant; these are the points where the two great circles or planes intersect and they coincide at the equinoxes. Thus they are the points in space and time where and when the Sun’s path lies on or crosses the celestial equator or congruently in the heliocentric perspective when the Earth’s rotation plane crosses its orbital plane. Each point can be either ascending (☊) or descending (☋). The passage of the Sun through this point into the northern celestial hemisphere is the vernal equinox (around 23rd March in the Northern Hemisphere) and the autumnal equinox (around 22nd September in the Northern Hemisphere) when it crosses into the southern celestial hemisphere. In terms of generalization and to avoid confusion with which hemisphere is the viewing point, it is often referred to simply as the March equinox and the September equinox. The March (vernal) equinox is that point which is known as the ‘First Point of Aries8 and is the point from which the celestial Right Ascension is measured. It is also the vernal equinox that is the point of reference from which all the zodiac divisions, and indeed the sky in general, are composed.

Within a certain perspective, the two equinoxes correspond to two states of equilibrium or balance in the celestial machinery and are an external projection of the equinoctial and solstitial cross. From this perspective, one could say that the two points of the equinoxes lie at the intersection of the two arms of the cross and represent the balance between the equatorial and the ecliptic circles. These circles are responsible for the diversity of the seasons and it is their difference or non-correspondence that causes variety in the seasons and hence the calendar. This is symbolically significant, for if the two great circles of the celestial equator and the solar ecliptic coincided, there would be complete uniformity. The divergence of the two circles ruptures the equilibrium, and this in turn engenders variable order throughout manifestation. Further, manifested existence is subject to an indefinite projection of complementary and opposite dualities because of this variable order. Each day becomes a manifestation of the disequilibrium and is therefore unique in the annual cycle. The Earth’s two cycles, its rotation on itself and its rotation round the Sun, diverge most at the solstice points. There is no equilibrium between the two cycles at these points; only opposition and contrast (Diagram 9.4). ( This point used to coincide with the zodiacal constellation of Aries some 2,200 years ago but because of he precession of the equinoxes it now coincides with the constellation of Pisces. This transition is not without its symbolic consequence.)

Without trying to labour this point unduly, all of manifest existence is subject to this complementary and contrasting projection, all manifestation being as it were composed of limited projections of the Universal complementary Principle of Essence and Substance. Each pole is universally reflected within each individual manifestation.

Whilst so far the cross has been used as a spatial symbol to characterize the opposition and unification of complementary but opposite principles, it is now shown equally to be applicable in a temporal sense. In fact, it is in the temporal context that the distinction between the opposing and complementary natures of the cross can be fully appreciated. In a complementary mode, the cross combines the annual orbital cycle with the equinoctial cycle of the Earth such that they are not oppositional. One cycle is compared to or superimposed on the other, both cycles exist in their own right and both are distinct in nature in the same way that Essence is distinct from Substance. This combination produces a unity of complementary principles, the centre being the exact point of unison of these principles (Diagram 9.5(a)). In opposition mode, the cross combines two pairs of equal but opposite tendencies (Diagram 9.5(b)). The summer solstice is opposed to the winter solstice and the vernal equinox is opposed to the autumnal. Rather than being two axes, the cross can be viewed as two pairs of opposing but complementary arms. Rather than being the point of union between the two tendencies, the centre becomes the pivotal point of symmetry around which the opposing tendencies are arranged. The two pairs are arranged about the centre or polar opposites; one pole is complementary to but opposite to the other, and both poles form the extreme positions inherent in the complete axis. In this way, the winter and summer solstices and their association with the ascending and descending nodes and achieve balance along the solstitial axis. The same holds true for the equinoctial axis. The centre of the cross in this instance becomes the resolution of opposites and the point of reconciliation, of synthesis, of all contrary terms, for points of crossing are contrary only from viewpoints that see only extremes and separate identities.10

Any sacred building orientated to the points of the compass symbolically manifests the balance of the Sun’s movements. The building plan laid out in the four directions of space on the ground becomes an architectural nomogram for the movements of the Earth and Sun. There is another aspect of solar symbolism related to the equinoxes. The equinoxes or nodes can symbolise ‘gateways’ or ‘doors’ in time that mark the transition of the Sun across from North to South and as such are spatial symbols for celestial mechanics. The symbol of the ‘gateway of the Sun’, referring to the Sun’s journey, can thus be taken spatially and or temporally. ( It could be said that this corresponds to the meaning of the word ‘cross’ as a noun or as a static configuration in space or as a verb as a ‘crossing’ in an active mode of the cross in time.)

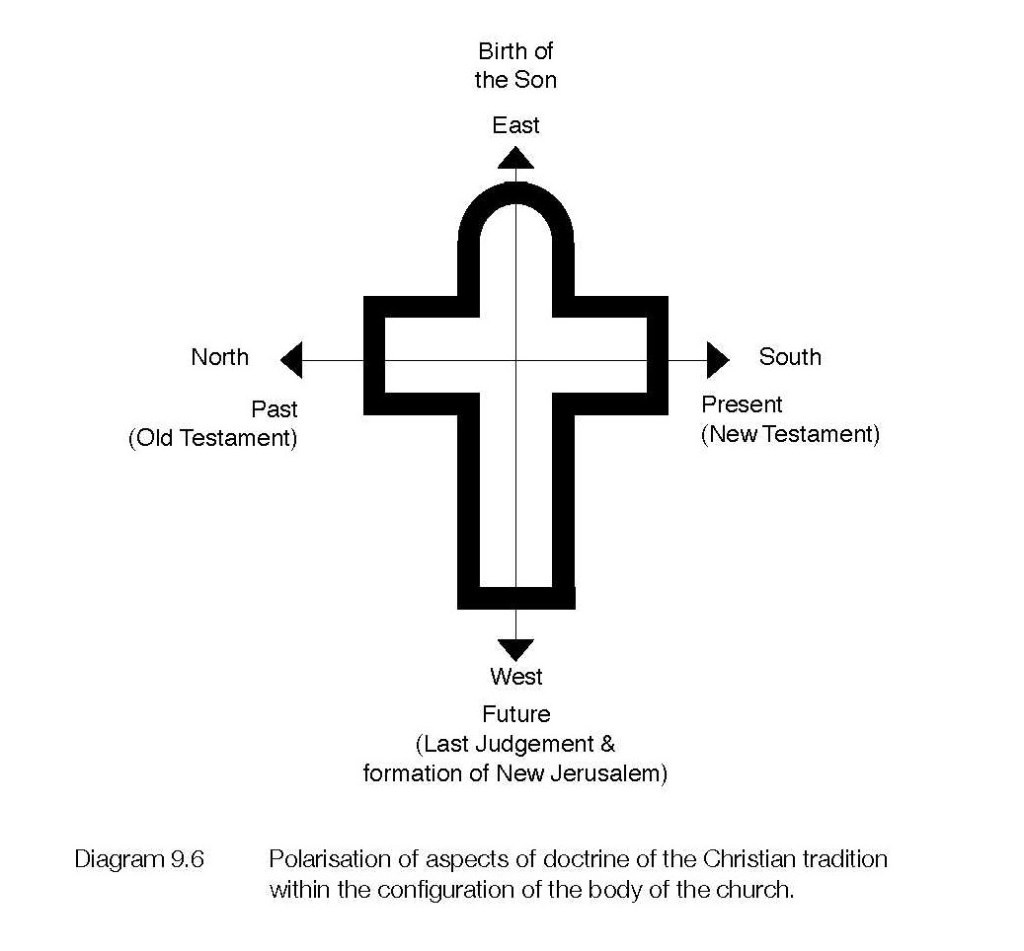

How all this can be incorporated into an architectural configuration can be seen in the distribution of iconographic images and sculpture in some Gothic cathedrals and is related to the principles of the static and dynamic modes of the Duad. The two principle axes of a cathedral can support complementary and oppositional symbolic couplets. For example, iconography, in the form of sculpture or stained glass windows, in opposing positions across the North-South axis, could depict the complementary polarisation of the Old and New Testaments. The East-West axis could symbolise the polarity of the birth of Christ as Saviour and the formation of the New Jerusalem (Diagram 9.6).

There is a variation of such a schema at Chartres Cathedral, where the northern Rose Window depicting the 24 kings, priests and prophets of the Old Testament faces the southern window depicting the 24 elders of the New Testament Apocalypse. Thus a temporal transformation occurs across the aisle, that is, in space (Images 9.1(a) & (b)). The East-West axis for its part conforms to the Immanent Principle within, of Christ’s mission in the world under the stations of Christ the Child (Man), Christ resurrected and Christ in Judgement.

- T h e C h i – R h o

Related to the use of the quadripartite division of the annual solar cycle and the symbolic ‘cross of solar motion’ is one of the most complex and enigmatic ancient Christian symbols, the Chi-Rho (Image 9.2). The Chi-Rho is a combination of the ancient Greek letters Chi (X) and Rho (P) superimposed such that the ideogram becomes a monogram. While the monogram was associated with Early Christianity, being a form of crux dissimulata ( The term the crux dissimulata is supposedly an attempt by early Christians to use the cross as a Christian symbol of faith but in a mode that was disguised or dissimilar) and Chrismon, ( Chrismon comes from a Latin phrase, Christi Monogramma, or monogram of Christ and are a family of symbols that relate the different aspects of the Person, life and ministry of Christ.) the symbol was already well established in Ancient Greece as part of the Orphic- Pythagorean Mysteries and was associated with Aeon Chronos and later Kronos. It was also an abbreviation of the Greek Chreston, meaning ‘a good thing’, and used by scholars to mark important passages of text. . The superficial connection with Christianity is twofold. First, Ch are the first letters of the Greek Christós (χρῑστός), later latinised as Christus and Christ. The figurative association with the crucifix or the cross of the crucifixion is obvious. Second, the Chi-Rho has an historical association with the Emperor Constantine I (306-337 CE) conversion to Christianity after his vision of the symbol and which he then used as a labarum or military standard.

The Chi or X component of the Chi-Rho in the more ancient examples depict a more flattened figure with the arms at a more obtuse angle than a right angle (Image 9.3(a)). There is an association of the more ancient and pre-Christian Chi or X to the ‘World Soul’ in Plato’s Timaeus.18 Plato relates that:

This entire compound he divided lengthways into two parts, which he joined to one another at the centre like the letter X, and bent them into a circular form, connecting them with themselves and each other at the point opposite to their original meeting-point; and, comprehending them in a uniform revolution upon the same axis, he made the one the outer and the other the inner circle. Now the motion of the outer circle he called the motion of the same, and the motion of the inner circle the motion of the other or diverse. The motion of the same he carried round by the side to the right, and the motion of the diverse diagonally to the left. And he gave dominion to the motion of the same and like, …19

The ‘circular form’ is most likely a metaphor for the great circles of the heavenly sky, the ecliptic circle and the celestial equator. The Chi is the point at which the celestial image of the supernal Sun crosses the celestial equator from one hemisphere to the other. The crossing paths coincide at the equinoxes. Thus Plato was seen by later church fathers as prefiguring the cosmic Chi or cross in the sky in a very Christian perspective, with St. Justin Martyr proclaiming that Plato ‘gives the second place to the Logos which is with God, who he said was placed crosswise in the universe’. The Chi-Rho takes on a greater symbolic potency when combined within the circle. The symbolism of the turning wheel combined with the turning of the great heavenly circles places Christ as the Logos, the centre of the cosmos (Images 9.3).

Images 9.3 (a) (Top left): Chi-Rho combined with the Anastasis, a symbolic representation of the resurrection of Christ. Panel from a Roman lidless sarcophagus from the excavations of the Duchess of Chablais at Tor Marancia (350 CE). (Top right): Chi-Rho symbol, detail from an altar stone. Limestone, third quarter of the 4th century. From Khirbet Um el ’Amad, Algeria .(Bottom left): Detail of Chi-Rho, from the Sarcophagus of St. Drausinus (Bottom right): Central panel of a Roman mosaic including the Chi-Rho found at Hinton, St. Mary, Dorset, UK.

- J a n u a C o e l i & J a n u a I n f e r n i

The two gateways previously discussed are known as Janui Coeli and Janui Inferni or the gates of Janus, the two-headed Roman god of openings, of beginnings and, more specifically, of passage and transitions.21 The first month of the Roman calendar year, January, retain this association as the beginning or opening of the year. The Janui Coeli is also spoken of in a broader context as the opening in heaven which is limited not only to space and time but is the subtle gateway to the empyrean, the gateway of ascension into heaven. Janus is the God of the doorway (januae) and archways (jani), symbolising the dual power of opening and closing.

The two faces of Janus were carved above archways and doorways of the city and his temples; they also symbolise the midwinter and midsummer ‘openings’ in the year. The temple of Janus itself was unique, a simple vaulted passageway that faced two ways and had two openings, a passageway from one world to another, from inside to outside, from war to peace. In this last context, it is not that far removed from the triumphal arch, exemplified by the Janus Quadrifrons arch, which however has four cardinal directions, rather than two arches (Image 9.4).

A different aspect of the duality is expressed by the terms Janua Coeli and Janua Inferni. Both relate to Janus and the world temple. The summer solstice, which occurs in the zodiacal constellation of Cancer, is the inferior gate, the gateway for men and symbolises the dying potency of the Sun, symbolised by the Janua Inferni. The winter solstice is in the sign of Capricorn and is the doorway of the gods. The Janua Coeli it is door of the Sun and its increasing power, the doorway identified with the opening from this world into heaven. The two terms define the two extreme points of the Sun’s passage around the ecliptic plane; they represent the opposing tendencies of advancing and retreating. The significance of the Janua is that they are the subtle doorways through which the cosmic ebb and flow of life proceeds in the wake of the Sun’s movement. As the entry doors of the solar extremes, they represent on one hand the opening door through which the Sun radiates existence and on the other hand the closing door which sees the Sun recede. ‘The Sun advances from the one gate, by the other he recedes,’ states Isidore of Seville. In other words the Januae Coeli and the Janua Inferni symbolize the regulating of the flux of existence, the inward and outward breath of creation (Diagram 9.7) ( The ideas of the janua coeli and the janua inferni have been absorbed into the Christian tradition intact. Burckhardt comments that ‘the two faces of Janus become identified in Christianity with the two Saint Johns, while a third face, the invisible and eternal countenance of the God, showed itself in the person of Christ’. Sacred Art East and West. There is also the related theme of the two crossed keys of St. Peter, one of gold (solar) and the other of silver (lunar) and the two pillars of Boaz and Jachin.

- Po l a r & S t e ll a r M o t i o n

The motion of the sun was previously discussed and it now follows to look at the symbolic motion of the starry vault itself and its particular application in the Chinese tradition in a sacred configuration known as the Ming T’ang. Simple observation of the stars shows that they progress during the night in a westerly direction, similar to the sun. This rotation presupposes a centre, called the celestial pole (Diagram 9.8), around which the stars rotate. The celestial poles are the points in the sky where the extension of the Earth’s axis would touch the outer limit of the starry sphere.28 To a night-time observer, the motion of the various ‘heavenly bodies’ is every bit as significant as the daily diurnal motion of the Sun across the sky, perhaps even more so as the celestial pole is revealed by all those motions that do not rise or set on the horizon. These stars are the circumpolar stars and vary depending on the latitude of the observer or place (Image 9.5).

Diagram 9.8 The great wheel of the turning sky pivots around the northern or southern celestial pole, depending on the hemisphere from which it it is viewed. Those stars that do not rise or set below the horizon are the circumpolar stars. These stars, star groups (asterisms) or constellations symbolically present as special class stars that are not subject to the annual motion of rising and setting.

Image 9.5 The great wheel of the turning sky pivots around the North or southern celestial pole depending on the hemisphere. Those stars that do not rise or set below the horizon are the circumpolar stars. These individual stars, star groups (asterisms) or constellations symbolically present as something other than the annual stars that are subject to the annual motion of rising and setting.

The celestial pole is the apparent pivot of the heavens, that is, the stars and other heavenly bodies appear to rotate about this point. This phenomenon is symbolically significant for traditional cultures that are familiar with the night sky. The celestial point is symbolically the hub or pivot of heaven and the fixed point of heaven. In the Chinese tradition in particular it has great significance. The pole star Pei-Ch’en has its image on earth as the royal palace, or the Ming T’ang, in China’s imperial cities. (The cycle of the precession of the equinoxes varies and is slowing down. The cycle is about 25,772 years or about one degree every 71.6 years. The reason why this is significant is that the current pole star Polaris is for the current era only. In 300BC the closest star to the North celestial pole was Thuban or Alpa Draco in the constellation of Draconis. By the year 3000 CE the pole star will be Alrai or Gamma Cephei )

The celestial pole in the Southern Hemisphere at the present is not located sufficiently close to a star to be termed a ‘pole star’ for the current era.

The celestial pole is the apparent pivot of the heavens, that is, the stars and other heavenly bodies appear to rotate about this point. This phenomenon is symbolically significant for traditional cultures that are familiar with the night sky. The celestial point is symbolically the hub or pivot of heaven and the fixed point of heaven. In the Chinese tradition in particular it has great significance. The pole star Pei-Ch’en has its image on earth as the royal palace, or the Ming T’ang, in China’s imperial cities.(‘The “Pivot of the Law” is what almost all

traditions refer to as the “Pole”. Also ‘In the Far-Eastern tradition, the “Great Unity” (Tai-i) is represented as residing in the pole star which is called Tien-ki, that is, literally “roof of Heaven”.)

This location is also the axis-mundi the ti-chung. It is the ‘ridgepole’, or ji, of the world and is the axis-mundi and the pole itself, as well as the point that stabilises earth and heaven. The word ‘pole’ in English also has the dual meaning of being at once a vertical shaft and a terminus or pivot, such as the North Pole or the Celestial Pole. This leads to a strong symbolic association between the vertical axis on one hand and the pole at the end of the axis on the other. It is the symbol of order and stability, the ‘pillar to heaven’, or tianzhu.32 The pole star is to the heavens what the omphalos is to the earth. This location upon the earth is ‘the place where earth and sky meet, where the four seasons merge, where wind and rain are gathered in, and where yin and yang are in harmony’ (Diagram 9.9). On the other hand, the Infinite and Ultimate are without a ridgepole, or Wuji, which is non-duality and Ultimate Nothingness, prior even to Taiji, the Supreme Ultimate (ridge) pole.It is through this relationship that the ‘Will of Heaven’ unfolds upon the earth.

- T h e L o S h u & H o T ‘ u D i a g r a m s

To illustrate in the Chinese tradition how the ‘Will of Heaven’ manifests, it is necessary to discuss briefly the cosmological diagram known as the Lo shu which is also known as the Lo River Writing or the Nine Halls Diagram. The Lo shu is related to another diagram known as the Ho T’u or the Yellow River Map. It is through these two complementary diagrams that the action of the ‘Will of Heaven’ takes place. Both diagrams have mythical origins in ancient Chinese antiquity. The diagrams also constitute the basis of several schools of feng-shui. The relationship with feng-shui and architecture is another entire topic but the primary correspondence here is with the relationship and understanding of qualitative number as symbol. Qualitative number or what in the Western traditions are referred to as Platonic Numbers sees number as expressive of principial action and relationships. Earlier in Chapter 2

of the example of the Octad was discussed in relation to form. This could be called an expression of ‘formal number’ and the Duad and Triad are similar expressions but taken at a more principial level. In the Chinese tradition, the use of formal and principial numbers is expressed in the disposition of space and related relationships and movements and is comprehensively applied to architecture.

The Lo Shu diagram represents a number of metaphysical considerations. ( The Lo Shu diagram according to some sources, was associated with the legendary emperor Fu Hsi and his discovery of the markings on the back of a tortoise and in fact there are numerous traditional depictions of the Lo Shu associated with the tortoise. As noted earlier the tortoise is a symbol of heaven above the earth and is a symbol of mediation, and the natural location for Man.)

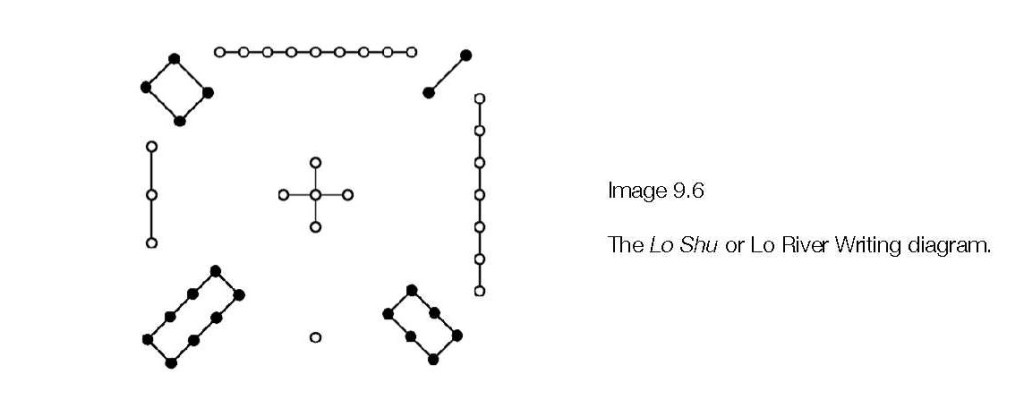

First, the diagram is made up of a number of open white or unfilled circles and black or filled circles. The white circles representing heavenly or yang odd numbers, while the black circles represent the earthly or yin even numbers. At the centre of the diagram is the number 5 expressed as a cross of white circles and, bearing in mind the number series 1 to 9, the number 5 lies midway and is the natural middle or mean. Above and below the central 5 are the numbers 9 and 1, to the left and right are the numbers 3 and 7, all as white or unfilled circles. The heavenly odd numbers in their figuration form a cross. At each corner of the diagram are the even, yin, or earthly numbers, also forming a cross but on the diagonal (Image 9.6).

The cosmological diagram known as the Ho T’u or Yellow River Diagram (Image 9.7) is supposedly more ancient than the Lo Shu diagram. At its centre it also has the symbolic heavenly number 5. Arranged around the perimeter are two outer squares of numbers. The bottom pair are the couplet 6/1, the top the couplet 7/2, the couplet 8/3 is at the left and the couplet 9/4 is to the right. Each couplet contains an odd, yang, or heavenly number and an even, earthly or yin number. The sum of the couplets correspond to the numbers 7, 9, 11 and 13 respectively.

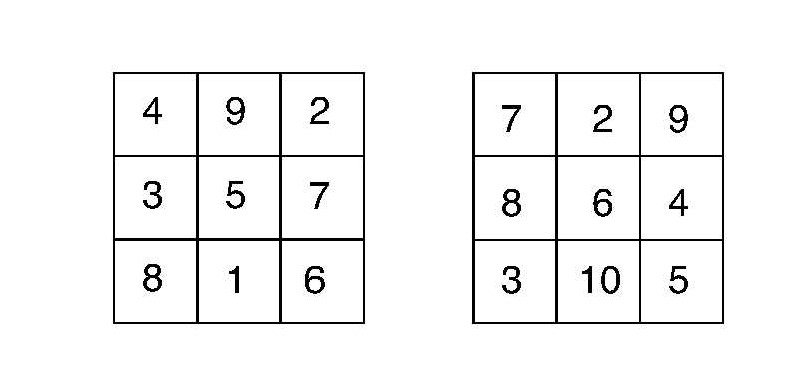

The distribution of the numbers in the Lo Shu diagram can be arranged into a 3×3 square known as the Lo Shu magic square, with the number 5 at the centre (Diagram 9.10(a)). The sum of each row, each column and each diagonal is 15. The number 15 is the number of the supreme principle, the Great Tao or T’ai Chi, the summation or unity of Heaven and Earth. The Lo shu magic square thus becomes a figuration of the action of Heaven on Earth. There is a complementary magic square to the Lo Shu that reflects the action of Earth upon Heaven (Diagram 9.10(b)). It may seem contradictory that Earth can influence Heaven, but it should be understood as the Principial nature of earth, not the physical earth. The diagrams thus show in numeric terms the reciprocity between Heaven and Earth. This reciprocity sees the Heavenly number 5 within the Earthly Lo Shu mirrored as the Earthly 6 within the centre of its Heavenly counterpart.

Diagrams 9.10 (a) Left: The Lo Shu magic square derived from the Lo Shu or Lo River Writing. The summation of each column, row and diagonal equals 15 (or =3×5).

(b) Right: The heavenly or reciprocal counterpart to the Lo Shu. The summation of each column, row and diagonal equals 18 (or =3×6).

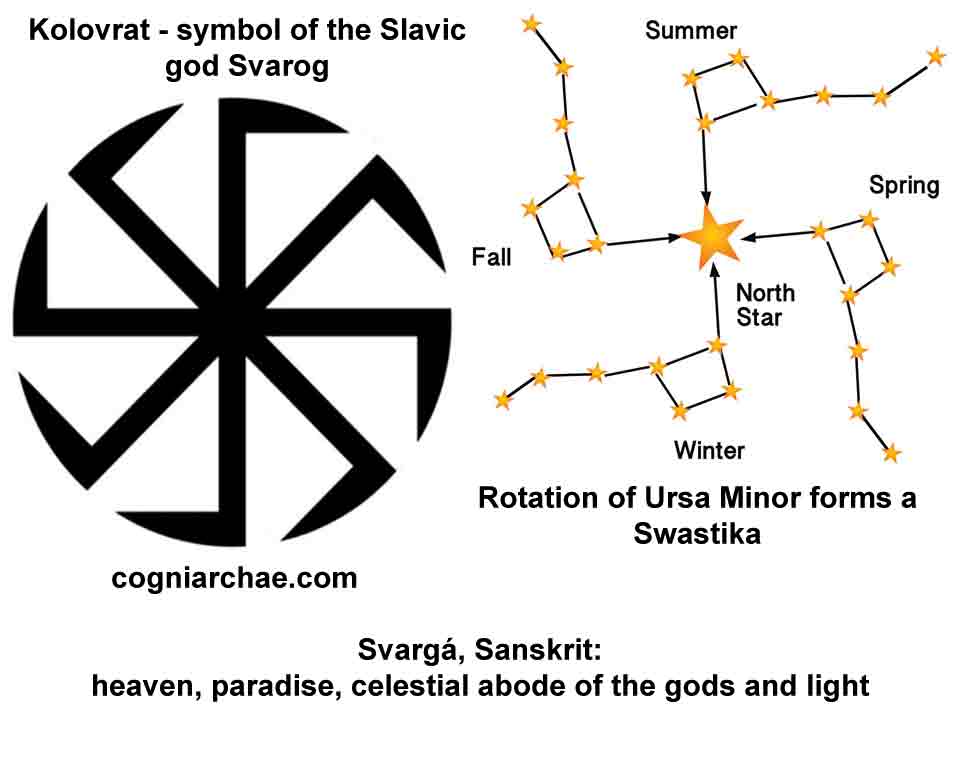

The Lu Shu has the outer couplets of the Ho T’u, namely, 6/1, 2/7, 8/3 and 4/9, arranged in its outer matrix in pairs, thus relating the two diagrams graphically. The four couplets in the Lu Shu form a swastika configuration when joined through the central square of 5, i.e., 6/1/5/9/4 and 2/7/5/3/8 (Diagram 9.11(a)). The same configuration of couplets and the arms of the swastika are present in the reciprocal celestial Ho T’u matrix, i.e., 7/2/6/10/5 and 9/4/6/8/3 (Diagram 9.11(b)).

Diagrams 9.11 (a) Left: The Lo Shu magic square with the Ho T’u couplets indicated as boxed rectangles form the basis of a swastika arrangement when connected through the central square of 5. (b) Right: Similarly the celestial counterpart to the Lo Shu magic square has the same Ho T’u couplets in the form of a swastika through the central square of 6.

In this sense the ‘magic squares’ are a true ‘matrix’. The word ‘matrix’ is derived from the Late Latin matrix meaning ‘womb’ and is related to mater meaning ‘mother’ from the Greek mētra meaning ‘womb’. The word matrix here is entirely appropriate with its productive associations more so then ‘magic square’.

Viewed another way, the matrices are the same, only the centre hub of the two crosses differs. Nor are the hubs themselves absolute in the sense that they are inverted images of each other. A total matrix would take into account a superimposition of one matrix on the other. If this is done, the centres 5 and 6 total 11. The same earthly and heavenly totals are expressed by the corresponding numbers if the two diagrams are superimposed. Thus 4+7=11, 9+2=11 etc, each number in turn expressing a reciprocal antinomic relationship of the permutations of unity expressed by the number 11.

The two diagrams are thus superimposed swastika mandalas, the axis of which is the invariable middle (the 5 and the 6) of each matrix. In the context of what has been said previously about complementary opposites, such as the cross of the solstitial and equinoctial axes applied to the annual motion of the Sun, the totality of the two superimposed principles constitute the union of the two solar modes in question. The same applies to the two modes of the Lo Shu, the reciprocal activity of heaven on earth and earth on heaven that results in manifestation and can be held in balance only by reciprocal principles. Man, located between the two matrices, views the two from a position of centrality; while the earthly matrix is turning clockwise, the heavenly matrix (viewed from below) rotates anti-clockwise. The interaction of the two numeric matrix mandalas with their swastikas can also be seen as the rotation of one upon its reciprocal counterpart, producing an endless array of superimposed dynamic relationships.

Symbolically, this interaction results in the unfolding of Universal Possibilities, including the temporal cycles as part of the ‘Will of Heaven’ over the Earth. In another mode, this is the fundamental significance of Yin and Yang, in which the totality is expressible only by the symbol of the unity of the two complementary principles, as in the interpenetrating diagram of the taijitu.

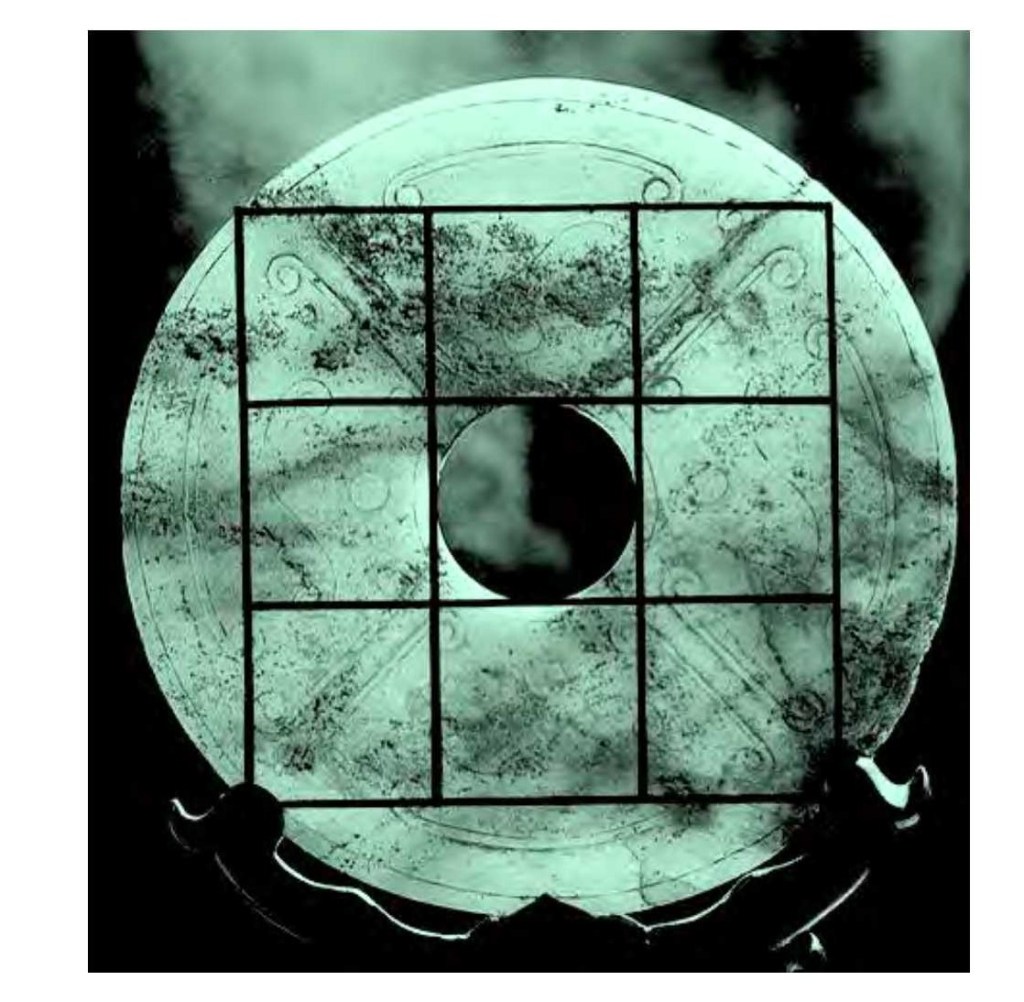

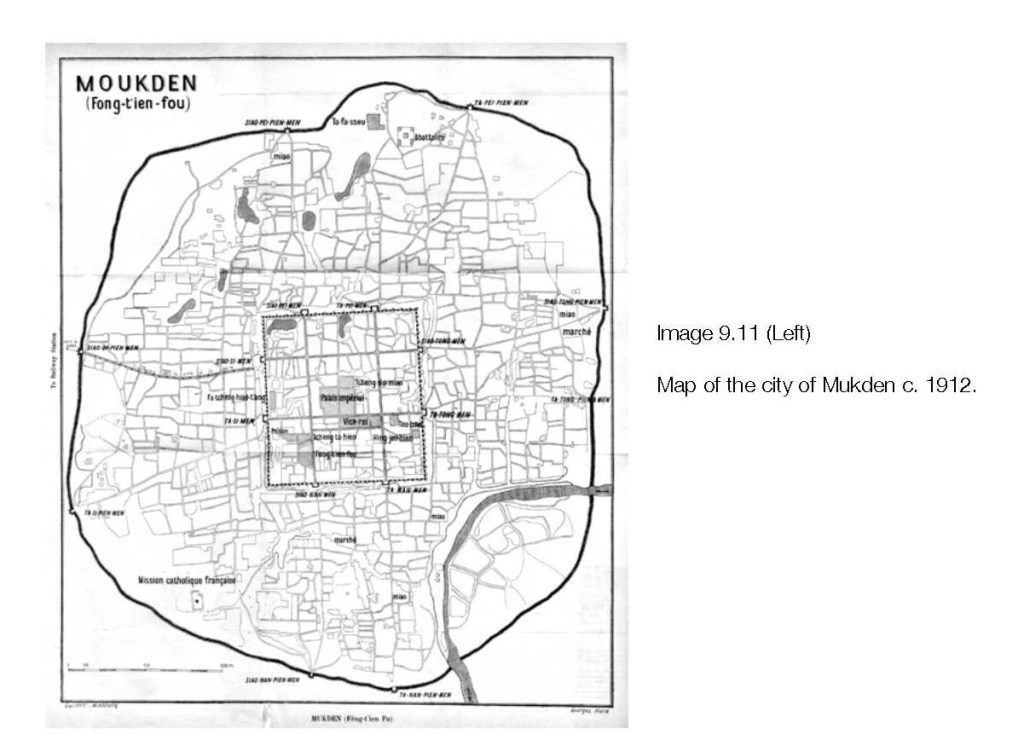

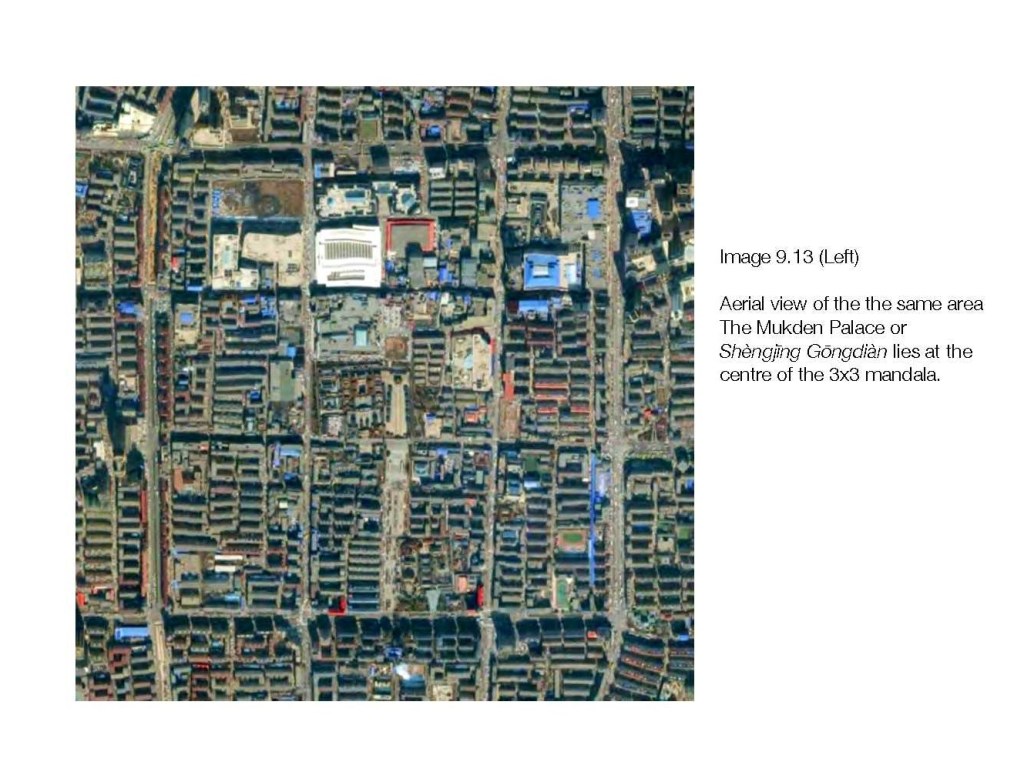

The above considerations also need to be examined in relation to the ninefold division of agricultural land known as Jingtianzhi (or jǐngtián zhìdù) and the Middle Kingdom of China. This 3×3 matrix of division was not so much an actual plan of subdivision but a principial template applied to geography, cities, towns, palaces and houses alike. The template has the central controlling square with eight ‘houses’ or four quadrants and four intermediate quarters following the eight points of the compass. The points of space also correspond with the seasons in a fourfold division (Image 9.8).

The 3×3 or ninefold Jingtianzhi division of land was applied to cities in ancient China. The capital city or seat of the emperor had a walled area of 81 li squares or 9 x9 li. Other older cities for minor royalty had to be based on 5×5, 4×4 and 3×3 li. The ‘Holy Field’ was also embodied in sacred ritual by the emperors to respect various agricultural rites. The emperor himself initiated the agricultural season by ritually ploughing the first furrow. The ritual field was a square of four mu and was divided into the 3×3 or nine sections, the number 4 corresponding to the yin principle and the number 9 to the yang principle. The ritual was thus carried out in the context of cosmological balance.

This is another example of ‘hierogamic exchange’ of qualitative numbers in the same way as the action of the Asuras and Devas in the Samudra Manthan (the ‘Churning of the Sea of Milk’). It is an interaction of consanguine entities that are from a certain perspective, mirror opposites but unified through exchange.

The Holy Field matrix may be related to the curious ancient Chinese ritual object known as the bi, which have been manufactured in China from neolithic times, generally in jade (Image 9.9). Early examples from the Zhou dynasty are regulated by the 3×3 matrix and result in the centre hole being proportionally regulated by the overall radius of the bi. The outer circle of the bi symbolises heaven and the inner circle is regulated by the earth, albeit depicted as a circle but also as a square in many ancient Chinese coins. Thus, yin and yang are in balance and the centre is a manifestation of order and heaven’s influence on the earth.43

Image 9.9 A Chinese jade bi disc from the Zhou dynasty. The relationship of the inner circle to the outer circle appears to be regulated by the 3×3 matrix of the Jingtianzhi or ‘Holy Field’.

The symbolic knowledge that led to the formulation of the Jingtianzhi can also be found in city and town planning (Images 9.10-9.13) layout of later palaces and many of the traditional architectural forms throughout Chinese history.

- T h e Swastika

Guénon, devotes a chapter in Symbolism of the Cross to a discussion of the swastika but concludes that ‘We cannot think of developing all the considerations to which the symbolism of the swastika can give rise’.46 Such is the complexity of this symbol. Similarly here the discussion will have to be one limited primarily to the Chinese tradition in this Chapter.47 However, similar metaphysical considerations could be applied to the Hindu and Buddhist traditions and in a limited context to Islam and even Christianity (Images 9.14, 9.15, 9.16 & 9.17).

In Chinese astronomy, the realm of the circumpolar stars was called the Purple Forbidden Enclosure and is one of the San Yuan or Three Enclosures of the night sky.49 It is the function of the axis-mundi to link the heavens with the earth, to link the centre of the heavenly vault, the pole star, with the centre of the earthly plane, the omphalos. From this perspective, the axis-mundi, like a giant axle, forms the pivot around which the heavens and earth revolve like two giant wheels. Important among the asterisms of this group are the seven stars of the Northern Ladle, or the Pei-tou constellation. The ‘cup’ end of the group always points toward the northern celestial pole and Pei-Ch’en. The group rotates like seasonal clock hands around the immovable centre of Pei-Ch’en.50 The Great Chinese historian Ssu Ma Ch’ien (Sima Qian, 145-87 BCE) wrote of the Pei-tou (northern Ladle) constellation:

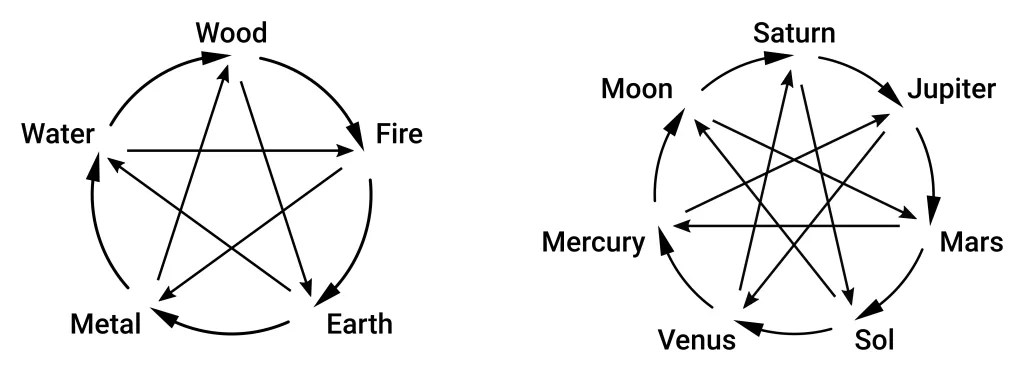

The Dipper is the Thearch’s carriage. It revolves around the central point and majestically regulates the four realms. The distribution of Yin and Yang, the fixing of the Four Seasons, the coordination of the Five Phases, the progression of rotational measurements, and the determining of all celestial markers — all of these are linked to the Dipper

The configuration of the Northern Ladle set in the sky and considered as simultaneously superimposed over the four seasons, is the configuration of the swastika (Diagram 9.12) so the pole star is totally assimilable to the swastika. The swastika (when viewed toward the heavens is arranged in a counterclockwise configuration but as discussed in regard to the Lo Shu magic square with the Ho T’u couplets can also be seen as projected upon the earth in an inverse way. Together they establish the celestial axis. At the centre resides the Supernal Lord and Thearch, Shang-di driving his heavenly chariot in the constellation of Pei-tou (Image 9.18).

seasonal positions forms the configuration of the swastika rotating in the sky.

It should be noted that the depiction of Pei-tou is inverted in Diagram 9.12 compared to that of Image 9.18. This is a common transposition with depictions of the night sky. Even today, the depiction of stars can be viewed either as inverted, which makes sense when looking at a star map in a horizontal plan, or in the direct relationship when holding the map up to the night sky, such as when using an orrery or planisphere. This is a common question with representations of the heavens on earth: is it from the viewpoint of heaven or of earth? Apart from technical considerations, there is a profound symbolism at work here. Transparency, reflections and mirror image are attributes only of the world and not the celestial realm. The complex symbolism in regard to inversion and the mirror was discussed earlier. As was discussed with the inversion of the counterclockwise and clockwise swastika, it is only the two aspects that present the entire symbol, as does the combination of the Lo Shu magic square with its complement, the Ho T’u (Diagram 9.13). The significance of the Lo Shu matrix with the Ho T’u can only be touched on here and the implications of its incorporation into the integrated vision of Chinese science and metaphysics is indeed profound.

Note: The handedness of the swastika can be explained as its turning, an action that can be related to its dynamic nature as a horizontal cross on a pole with four flags attached. The clockwise turning is the flags or arms trailing behind the cross, such as in Image 9.16, or trailing fire, as in a spinning Catherine Wheel. Whone, Church Monastery Cathedral: A Guide to the Symbolism of the Christian Tradition (Tisbury: Compton Russell Element, 1977), 161. Technically the swastika is the counterclockwise rotating mode and the clockwise rotating mode is the sauwastika.)

Read also : The Thread of life: Wisdom for our Times

- T h e Ming T ’ a n g & t h e ‘ W ill of H e a v e n ‘

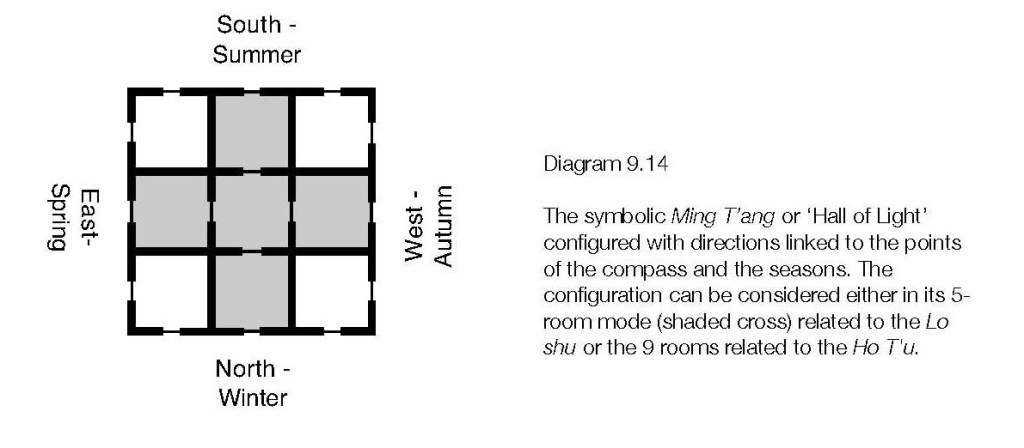

The Chinese cosmological and architectural schema known as the Ming T’ang embodied all the above considerations and more. The form of the Ming T’ang was the embodiment of a spatio-temporal and cosmological template that derived from the interaction of principial number configured upon a cruciform plan. As a subtle form rather than an architectural manifestation, the Ming T’ang exists as a formal idea as the abode of the Emperor. It is located at the ‘Invariable Middle’ or Ching-Yung. As the earthly ‘Hall of Light’ it represented the palace in which the Emperor dwelt as representative of Man situated midway between Heaven and Earth. The Ming T’ang comprised either 9 or 5 rooms, depending on the source consulted. The 9-room plan corresponded to the Lo shu and the 5-room plan to the Ho T’u diagrams (Diagram 9.14).

In other related versions of the Ming T’ang there are twelve ‘rooms’ or ‘views’ facing the four cardinal directions. To be represented in corporeal space, a limited representation is needed to reconcile the cross of the Ho T’u, the Lo shu and the twelve rooms or openings of the Ming T’ang. One way is to consider three openings on each of the four sides of the 3×3 matrix of the Lo shu square as the 3×4=12 openings. Alternatively, each corner room is divided into two and with the four centre rooms giving the twelve rooms of the Ming T’ang. In another possible arrangement, the twelve rooms could be seen as rooms surrounding a central Ho T’u, the cross of the Ho T’u acting as hallways, not rooms (Diagram 9.15).

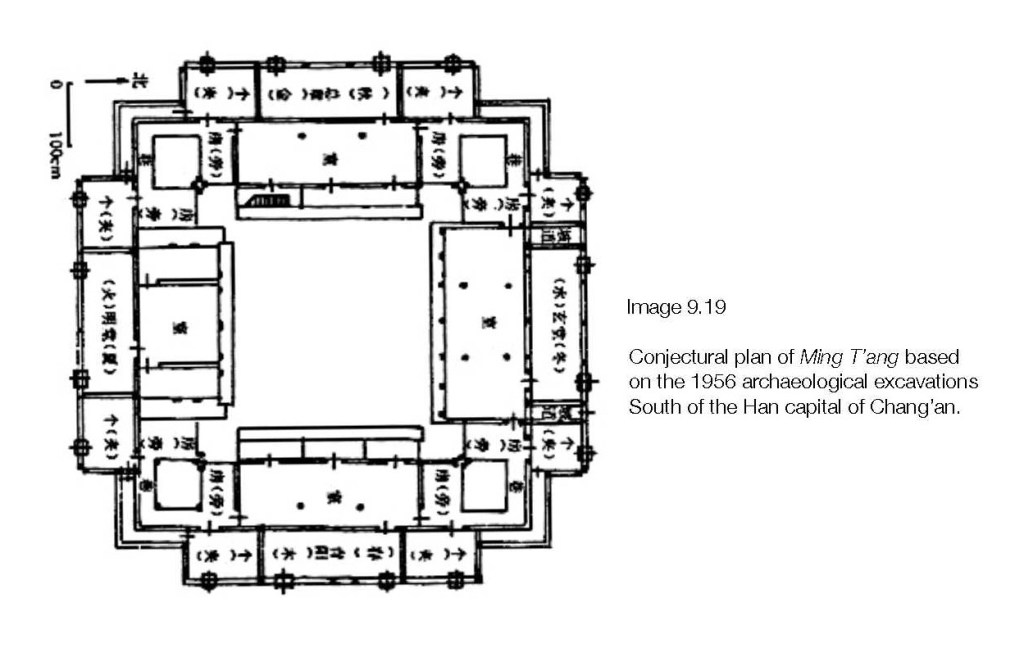

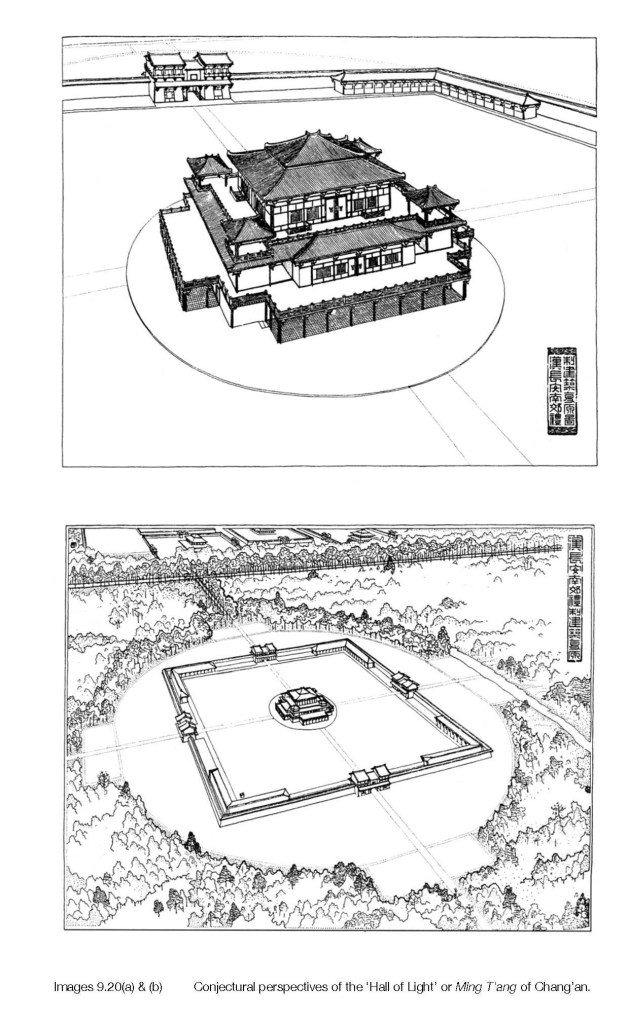

The Emperor dwelling within the Ming T’ang moved ritually around its rooms (houses), following the cycles of the Sun and seasons and emulating his ritual tours of the empire every five years. Thus the Emperor’s role was to be a ‘regulator’ of space, time and the universe, to be an intermediary between Heaven and Earth and all according to primordial numbers. The Ming T’ang was built during various periods of Chinese early history. However, there are no Ming T’ang palaces remaining, although there are archeological remains that correspond strongly to the geometric models discussed here. For the purposes of this research, however, its significance lies not in its historical execution but in its mathematical and symbolic formulation (Images 9.19, 9.20(a) & (b).

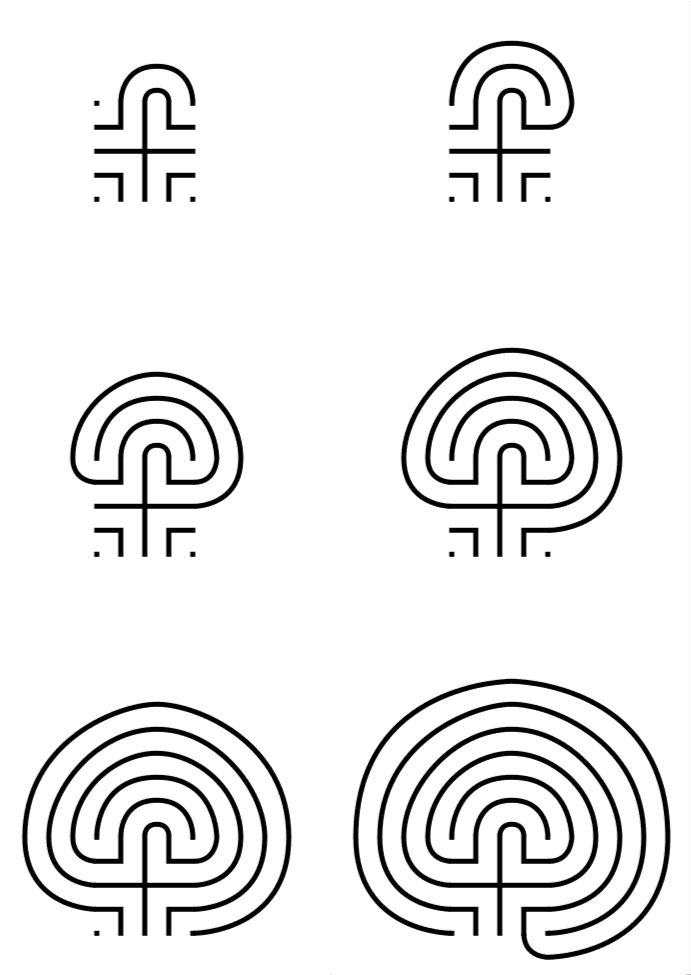

- Lo-Shu and the labyrinth

A journey from the primordial China of the legendary rulers to the maze of the palace of Knossos to the sovereignty of Saturn, in an attempt to unravel a plot which – like a dance – turns out to be based on rules animated by a lost science of rhythm whose vestiges are manifested in diagrams cosmological information informed by the observation of the highest heaven: the circumpolar region as it must have appeared in 3000 BC, different from the current one due to the precessional cycle.

We do not know how the original concept of the labyrinth, probably Minoan, was born. In any case, it was more concrete than the Greek references cited indicate, because the definition of “remarkable (stone) structure” sounds derivative and vaguely metaphorical. It is conceivable that the name of a certain structure attributed to Daedalus became a generic designation — as happened, for example, with the proper name “Caesar,” which came to mean the epitome of sovereign power and rank, as reflected in the German word “Kaiser” and the Russian word “tsar”.

Kern thinks it more likely that the primary use of the word was related to a dance, whose pattern would “crystallize” much later in permanent forms, such as graffiti, petroglyphs and – finally – built structures. However plausible it may seem, this hypothesis does not shed much light on the first meaning of this drawing and on the reasons for its established form, the one we usually refer to as Cretan o knossian. Nor does it explain why such an important “structure” as a king’s palace should have the shape of a dance path.

While it is true that a Latin given name such as Caesar has come to mean “the epitome of sovereign power and rank”, on the other hand we may find that the English word King and the German one King may share a common root with the word having the same meaning in the Turkic and Mongolian languages: Khan

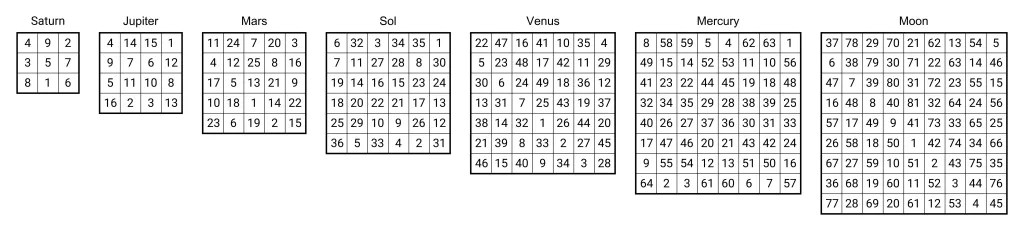

Is there any evidence that the Cretan-type labyrinth owes its shape to some earlier archetype? An appendix at the end of the first chapter of Kern’s book suggests a possible relationship between the design of the labyrinth and the “magic squares” made up of an odd number of squares on each side. The origin of the custom of associating magic squares of different sizes with the seven “heavens” is extremely difficult to determine, both historically and geographically. We find mention of it in the treatise De Occulta Philosophia libri tres by Cornelius Agrippa . Albeit based on earlier works , is the first to have known a great diffusion in the western world. According to these accounts, the elements of the sequence are ordered as follows:

Regarding this order, understood from the highest to the lowest sky, it can be noted that it differs from the one traditionally used to number the seven days of the week: in this regard it is worth mentioning one of the two explanations provided by the Roman historian Cassio Dione in his monumental work Roman history:

As for the custom of referring the name of the days to the seven stars called planets, we know that it was invented by the Egyptians, but it is also practiced by all peoples. Its introduction is relatively recent: in fact the ancient Greeks, as far as I know, did not know it. Since we find it among all peoples and among the Romans themselves, who now consider it their own in a certain way, I want to speak briefly about it and say how and in what manner it was formed. I have heard that there are two explanations, not really difficult to understand, which rest on a different criterion. In fact, if one were to apply the so-called «tetrachord» harmony, which we agree in considering the basis of music, to those stars which make up the decoration of the sky, in the order according to which each star moves, and starting from Saturn, whose circle is the farthest, and then skipping the two stars that follow, stops on the fourth, and after it, skipping two other stars, reaches the seventh, and retracing all the planets in the same way, assigned the days the names of the gods who oversee the planets, he would find that all days agree in a certain musical way with the harmony of heaven.

Tracing this double sequence reveals, surprisingly, the same logic illustrated by another cosmological diagram belonging to one of the few ancient civilizations that lasted to the present day: that Chinese.

The striking feature of magic squares composed of an odd number of squares is that the arrangement of the odd numbers forms the generating pattern from which a seven-circuit Cretan-type maze can be derived. This fact becomes more evident in larger magic squares [8].

The first written evidence we have of a magic square are Chinese and concern the simplest one, the one linked to Saturn. Notably, the son of Heaven and Earth was the only god in the Latin pantheon said to have once reigned over gods and mortals alike in perpetual spring. Saturn is the god who presides over agriculture and harvest time, the king of golden age. This can lead us to conclude that, at least in classical antiquity, the divinity corresponding to the seventh heaven embodied the very archetype of royalty.

The study of kingship in early China reveals a close relationship with astronomy, which in turn is associated with an institution known as Ming T’ang, Hall of Illumination, of Light or, literally, Luminous Hall, where things were clarified. The character Ming (明) of his name is composed of the two great luminaries of the sky, the sun and the moon, placed in opposition, and is significantly applied to the room in which they were observed.

On what principles was this institution founded? Who was its founder and when was it founded?

[…] the authority of the Ming T’ang resided “in Yi of Fu Hsi”, the first legendary ruler, whose dating is fixed by the ancient tradition around 2852 BC, and who was one of the Five Ti deified as rulers of the seasons. The Touched (literally: “The eight diagrams”) attributed to him was the octagonal shape of the Yi, or astronomical “changes,” for which it appears to have been invented. [10]

The design of the Ming Tang was based on Touched, usually octagonal in shape, but traditional sources use to correlate it numerologically to Lo-shu, the magic square of order three. Its figurative representation recalls the shape of a turtle. The middle number is a cross made up of five connected dots. The corresponding element of the Pa-kua is the symbol yin-yang.

Marcel Granet highlighted the presence of one swastika implied is in the Lo-shu than in another magic square which is its celestial counterpart. The two were engraved on wooden tablets, free to rotate around a common central axis. This tool was used for the ritual orientation of buildings.

A parallel has been considered between the meander of the swastika and the drawing of the Labyrinth (Kern, Cook):

Only the influence of the swastika’s rectangular meanders can explain the singular fact that most of the early coin labyrinths from Knossos resemble the swastika in their rectangular shape. With this in mind, Arthur Cook may be right in regarding the swastika as a symbol of the labyrinth.

This is particularly noteworthy, if we keep in mind that – at least originally – the swastika it is not a symbol of the sun. Confucius says:

Governing with Numb it means to be like the North Star, which remains in place while all other stars bow towards it.

This idea is closely related to the Taoist notion of Wu Wei (literally translated as “without action”), which is not a passive attitude but – on the contrary – it is the ideal condition from which the sovereign can exercise his polar activity. The ideal ruler must be to the kingdom what the North Star is to the sky. This achievement requires the ruler to conform to the divine mandate e the loss of this conformity necessarily implies a loss of legitimacy for the ruler himself. Ecosystem’s staff is Lo-shu it is a synthetic diagram of the Divine Commission.

American archaeologist and anthropologist Zelia Nuttal was the first academic author to support the theory of the polar origin of the svasta with empirical observations]. However, she associated this design with a stylization of only the two bears. This might give an idea of the origin of the double meander motif in its square shape, but it might not be as satisfactory in explaining the design of the symbol yin-yang: if there was an exact match between lo swastika and yin-yang what would the colon represent? Because the latter consists of a double meander and two points instead of four points or four meanders ? The answer could come from an unexpected source: Bianchini’s planisphere, a map of the sky from the Hellenistic era whose fragments were found in Rome during excavations on the Aventine Hill in 1705 .

The core of the sky map is centered in the center of a dragon, which coils around Ursa Minor on the dragon’s head side and Ursa Major on the opposite side. Due to a phenomenon known as the precession of the equinoxes, the position of the North Star has changed over the millennia. The time when it was halfway between Ursa Major and Ursa Minor can be fixed at around 3000 BC, the time of Fu Hsi, the first of the three rulers to whom the Touched – according to tradition – it owes its origin. Needham was unable to find any documentary evidence to date the Lo-shu before the XNUMXst century AD ], but — as the American sinologist John Major later noted — the diagram of the five processes (Wu xing) could be derived from it. The exact correspondence between numbers and elements in their traditional association would otherwise be an extraordinary coincidence. This would allow you to backdate the Lo-shu of five centuries.

The Ming T’ang was first built according to the design of Shên Nung”, the Divine Farmer and legendary second emperor, whose date is traditionally given between 2736 and 2705 BC, and who was the second of the Five Ti.[19]

Shen Nung, the Divine Farmer, who taught men how to plow and basic agriculture. The Book of Lord Shang he speaks of his times as one of golden age and plenty, when he could rule without the need for a judicial system or public administration and could reign without the need for arms or armor. Sometimes he is symbolically represented with the head of an ox on a human body . Shên Nung is credited with “sacrifices to predecessors” nei Ming Tang. The “five grains” that grew in the summer, harvested in the autumn and stored in the winter were tasted and offered to the Five Ti, the rulers of directions and seasons .

The Ming T’ang was the first national song center and the dances were accompanied by musical instruments. It was music that brought down spirits; and this belief, or at least this practice, has continued down to the present day, especially on the occasion of the most important sacrifices. Music has always been used to call the spirits on the occasion of the two solstice sacrifices, the equinoxes and the welcoming of the four seasons.

It is worth noting that in ancient China (since at least the XNUMXth century BC, according to Sung dynasty historians) the death of a chief was followed by a dance known as “Dance of the Crane“, and eventually the dancers could be buried alive along with the dead leader ]. The Dance of the Crane (Greek: Γερανός) is the same name that we find associated with the celebration of the killing of the Minotaur by Theseus, performed by young Athenian men and women, otherwise destined to be ritually sacrificed to the foreign ruler.

- Sacred Architectural Order in Sufism

From Cosmology and Architecture in Premodern Islam

An Architectural Reading of Mystical Ideas By Samer Akkach

As a cosmic prototype based on numeric symbolism, the Ming T’ang is related to Chinese tradition at all levels of science, mathematics, geography and the geopolitical foundation of the Kingdom. It was a symbolic schema and embodied a traditional early Chinese worldview. The Ming T’ang is essentially a cosmological symbol in a crystallised form, a mandala, pure and simple. As Guénon comments, ‘The Ming T’ang was an image of the Universe not only in a spatial but also in a temporal sense, because in it the spatial symbolism of the cardinal points was directly associated with the temporal symbolism of the seasons and the annual cycle’. Its entire form is based on the resolution of the complementary opposites of Heaven and Earth, Sun and Moon, Winter and Summer and Autumn and Spring in order to express the Will of Heaven.

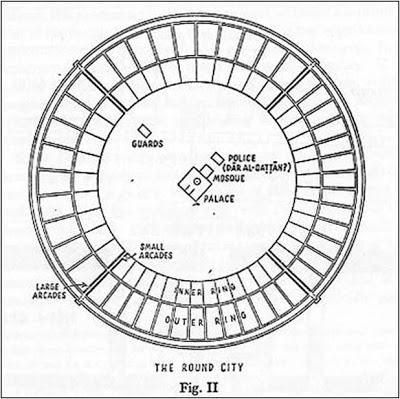

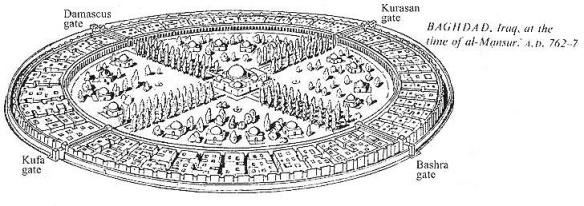

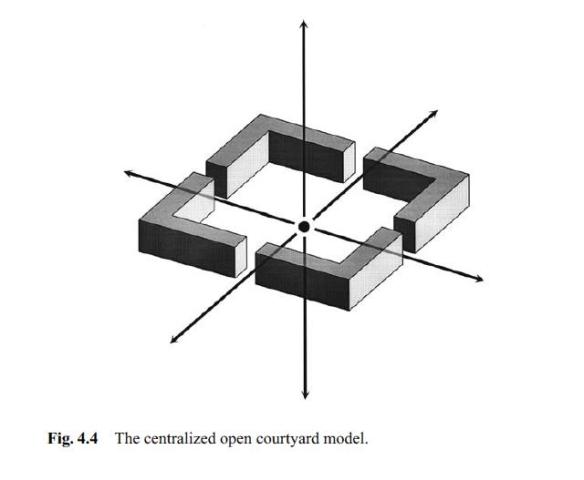

The planning of some of the early Islamic cities, such as al-Kufa, al-Basra, and Baghdad also follow the model of a centralized open courtyard. As described by Muslim chroniclers, they were laid out around a large open court (sahn) centered by one or two buildings—a mosque in al-Kufa and al-Basra and a mosque and the caliph’s palace in Baghdad, revealing the same underlying spatial order at a larger urban scale.

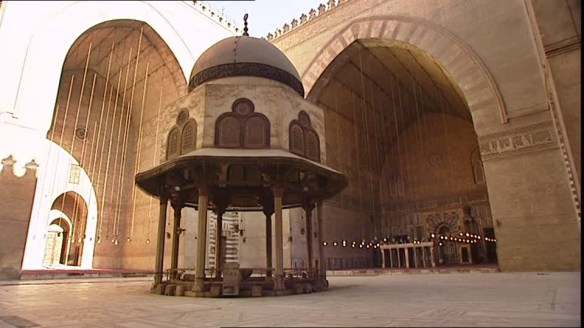

Fig. 4.4 The centralized open courtyard model.

The courtyard of the Sultan Hasan school in Cairo showing the geometry and spatial order of the centralized open courtyard model.

Linear Composition

The linear composition is a variation on the concentric composition involving repetition. The repetition of a concentrically ordered unit generates a linear com-position, conveying motion and extensionality. The linear composition can be seen primarily in premodern bazaars, such as those still existing in Isfahan,

Kashan,

Aleppo,

and Jerusalem.

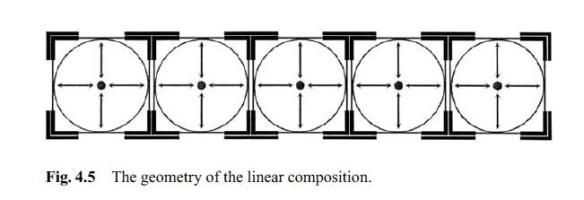

The repetitive form might have been generated by structural necessities, yet the spatial characteristics of the linear spaces are expressive of the same spatial sensibility that underlies the concentric compositions. While maintaining the order of centrality, axiality, and quadrature, the linear composition is created when the stationary center of a concentric space “moves,” so to speak, manifesting through this motion a linear space that joins two or more points.

In contrast to the concentric composition, the linear composition represents all spaces that are focused by a “moving” center, expressing the underlying spatial order in a dynamic way. Movement enables reiterative exposure to a similar formal unit and spatial structure, the arched base and domed roof, creating a sense of monotony and repetition. Colonnades, porticoes, and spaces covered with a multidomed structure, typical of Ottoman architecture, share with the bazaar its linear, dynamic characteristic.

Fig. 4.5 The geometry of the linear composition.

Architecturally, the linear composition is formed by the repetition of a spatial unit, creating a number of individual concentric spaces or “spatial pulses.” These units are linked together in a manner analogous to the way beads of a rosary are connected upon its thread. The monotony of linearity is often interrupted when the main route of the bazaar intersects with another or when the entry to a building is emphasized. These interruptions produce a series of nodal points that break the regulating monotony of linearity.

Whereas the static unfolding of space in the concentric composition reveals one center in a pictorially unified space, the dynamic nature of the linear composition manifests a multitude of centers, all of which are of more or less equal importance.

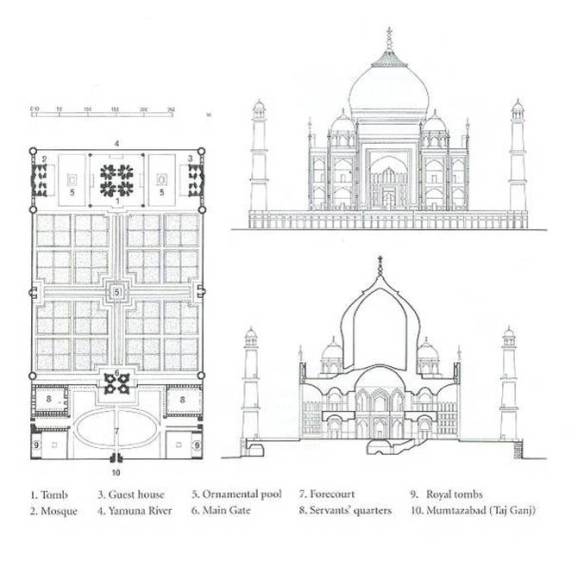

As a series of “spatial pulses” they embody in a repetitive manner the same underlying spatial order and reveal similar spatial characteristics. An architectural composition that is concentrically ordered may also comprise a multitude of centers, but usually varying degrees of importance can be distinguished. A geometrical analysis of the plan and form of Taj Mahal, for example, shows how the central space is distinguished in size and articulations from the other similar but smaller spaces, which nonetheless reveal the same underlying spatial order as the whole.

From an analogical perspective, one may observe that the concentric composition is the basis from which the linear composition derives, just as the point is thought of as the prin-ciple from which the line extends and stillness (sukun) as the state from which motion (haraka) proceeds.

Note: Spatial Connection Systems of the Bazaar

The form of a traditional city is based on its movement systems, of which the most important architecturally is the order of the bazaar. Each system, like a mode or dastgáh in music, is the most stable and least changeable part of a given expressive form.

Essentially, the bazaar is the line which ties the city into a totality as it moves between two points, the entrance and exit to the city itself.

As the musical mode gives scale and structure to the overall composition, so too the line of the bazaar gives the overall scale and structure of the city’s form.

Each mode (dastgáh) of Persian music has its own special repertoire of melodies (gashah-ha) which explore the most characteristic aspects of the mode. The melodies evolve from the mode in a system corresponding to the traditional spatial connection system.

The spatial connection system of the bazaar dictates how one moves between encounter points. While traversing the line of the bazaar you meet first the dependent indoor spaces. These spaces rely for their existence upon the primary, secondary or nodal spaces, such as stores and shops along the bazaar route.

Occasionally you come upon another kind of opening, and this leads to nodal spaces. Nodal outdoor spaces, as seen in the caravanserai which sterns from the primary movement system, are essentially rooms around a courtyard. Nodal indoor spaces, as seen in the timchah, are essentially rooms around a covered courtyard; there is usually a centra] pool, and the roof often has an open oculus. Read more here

Cosmic Order in Sufism

- The Original Idea

In ‘Uqlat al-Mustawfiz Ibn ‘Arabï asks us to consider the situation of a person seeking shade and protection, who thought of the idea of a canopy. To build the canopy, however, he first had to prepare the ground and lay down the foundations. In seeking shade and protection, the foundations are the last thing to be thought of yet first to exist.

The canopy, by contrast, is the first thing to occur in the mind but last to exist. This is the situation of the world, Ibn ‘Arabï says. When God thought of revealing his “hidden treasures,” the first thing that occurred in his mind was the idea of humanity. To fulfill this idea, he first had to bring the entire world into existence to form the foundation for human existence. Although last in existence, humanity was the original idea.

Humanity could not have existed without the world, just as the canopy cannot stand up without the foundations. And just as the foundation alone without the canopy is meaningless, for it provides neither shade nor protection, so likewise the world without humanity is purposeless, for it lacks the core being for whose purpose it was brought into existence.

The celebrated thirteenth-century Sufi Jalâl al-Dïn Rtimï restates Ibn ‘Arabï’s idea in a poetic manner, drawing our attention to the fact that the outward appearance of things often conceals the inner reality. He writes:

Externally, the branch is the origin of the fruit;

intrinsically the branch came into existence for the sake of the fruit.

Had there been no hope of the fruit, would the gardener have planted the tree? Therefore in reality the tree is borne of the fruit,

though it appears to be produced by the tree.

The Sufis along with most premodern Muslim thinkers advocate the view of a purpose-built cosmos designed by God for the accommodation of humankind. Man is at once the center, the model, and the ultimate aim of existence. The ontological correspondence between man and the cosmos was complex and multilayered. It was conceived and presented in a variety of ways in premodern Islamic sources, although the structural core concerning the three-dimensional cross was consistent. Texts such as, for example, the Ikhwân’s Rasâ’il, Ibn Tu-fail’s, Hayy bin Yaqzân, Ibn ‘Arabï’s al-Tadbïrât, and al-Jïlï’s al-Insân al-Kâmil, reveal rich and sophisticated conceptions underpinned by a firm belief in a universal order and structural resonance among the various levels of being. This was not peculiar to the Islamic tradition, of course. In fact the term cosmos, from Greek kósmos, denotes the idea of “order” and “ornament,” meaning the universe as an ordered and ornamented whole. The Arabic equivalent, kawn, as already discussed in the Tree of Being, designates the “cosmos” as an embodiment of the metaphysical order. “Cosmic formation” (takwïn) refers to the materialization of the immutable essences (al-a’yân al-thâbita) in the form of the external essences (al-a’yân al-khârijiyya), revealing the last three states in al-Hindï’s hierarchy: the world of spirits, the world of similitude, and the world of bodies. These worlds correspond to the three modes of cosmic existence: spiritual (jabarüt), angelic (malaküt), and human (nâsüt).

In the metaphysical order, the human presence was presented as mediating between God and the world. This is as far as the designative mode of creation (taqdïr) is concerned. In the cosmic order, it is the cosmos that mediates between God and man, as far as the productive mode of creation (ijad) is concerned. The patterns of universal manifestation project into the realm of existence through the production of cosmic forms (al-suwar al-kawniyya).

Acting as a link between God and man, the cosmos comprises the formal, imaginable, and communicable vocabularies, which constitute the alphabet of the language of symbolism. By means of this alphabet human imagination is able to function, as already discussed, and by means of the governing order one is able to retrace the geometry of existence according to which the world is fashioned. Read more here

- Saint George and the dragon Cult, culture and foundation of the city

The figure of St. George fighting the dragon is an icon in the Eastern and Western world: the topos of the glorious and sacred image, the Saint on horseback with shield and spear, opposite to the winged monster comes from ancient times and places, subject to devotion and dedication.

From Palestine to England, from the Balkans – the sources agree that George was born in Cappadocia – to Catalonia (San Jordi), the figure of the saint also defines morphologically one of the most important martyrological cults in Mediterranean area.

Following the insights of René Girard, which describes the violent origins of human culture, I propose to analyze through the traditional image of St. George, the foundation of the “enclosed city”, model of the Mediterranean city during the Middle Ages, with particular reference sacrificial origins of living space.

The term “enclosed city” refers, specifically, the priority establishment of the Mediterranean city in the sacral area Christian. We recall, among other things, that the cult, the culture of the people who grow and the civilization of who builds the city limits are linked from the common reference to the cult, and not just etymologically.

Worship, cult and culture are, in fact, even the mythical-ritual moments of a single human being on earth, in its anthropological, historical and institutional and political-symbolic.

The continuity between the ancient world, medieval and modern can be analyzed and understood through the cults, the stories and legends of the patron saints and the rituals related to the different moments of the organization of the medieval city space, and their persistence politico-religious in the modern city.

The construction of the city is symbolically oriented toward a centre, the centre of forces and the centre from which it receives direction and strength. The town we are dealing with is enclosed, “strengthened” in a double sense: as an area defended by walls erected in a perimeter boundaries, and as a place founded by a collective force. Thus, from the ancient rite of moenia signare aratro, yet there was no distinction between the figure as supreme military chief, king and priest, the first form of a built space defines, unambiguously, the peaceful order that, within walls, exercises control over nature undifferentiated….

- The city

In Judeo-Christian tradition, the city is considered as a negative reality.

The first mention we find in the Bible about the city, is the story of Cain and Abel, where Cain is described as a builder of cities. ( Genesis 4, 17.)

After his crime, Cain is presented as the ultimate wanderer who tries to mend its ties with the earth and the human community cut off from his violent act. ( See R. Girard, La Violence et le sacré, Paris, Grasset, 1972. On Cain and Abel, see also M. S. Barberi, Adamo ed Eva avevano due figli, in D. Mazzù (editor), Politiche di Caino. Il paradigma conflittuale del potere, Transeuropa, Ancona-Massa, 2006, and id. Misteryum e ministerium. Figure della sovranità, Giappichelli, Torino, 2002. On violence and Bible, see Giuseppe Fornari, L’albero della colpa e della salvezza. La rivelazione biblica della violenza in D. Mazzù (editor), Politiche di Caino. Il paradigma conflittuale del potere, cit. p. 159 ss. See also Enzo Bianchi, Adamo, dove sei?, Qiqajon, Bose, 1990. Couriously, the legend of ROme foudation tells about two brothers, Romulus and Remo. The history is so well known, but the collective memory of a violent city’s foundation bring back to a sort of geological stratification, where ritual, tale and myth are postponed continually. See the insights of Michel Serres, on: Roma, il libro delle fondazioni, Hopefulmonster, Firenze, 1991.)

Instead of being considered the place where humans reside, the city is presented as an artificial product, made by men to protect themselves, following a transgression that has destroyed the organic bonds of community. This view becomes explicit in the second quotation of a biblical city.

This view becomes explicit in the second quotation of a biblical city. Figures of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11, 1-9) and the city of Sodom (Genesis 18-19) we have a situation similar to the story of the garden of Eden, in which human beings aspire to build their fate entirely, hence moving away from the precepts of the Lord. Later, another city made its appearance.

This is Jerusalem, the city of God, based not on human wisdom but on the divine promise. But even here, in the practice of injustice, the holy city can become a prostitute, just like in the cities of pagans, Babylon the Great. (See Isaia, 2, 2-4. The book of Revelation, by St. John, will take back the image of Babylon as a satanic model of the city. and Surate 2 Al Baqrah, the Cow)

In the New Testament, the disciples recognize Jesus as a righteous king. But Jesus himself dies thrown out of the city (Heb. 13, 12-14), and confirm with his death shocking not belong to the Kingdom of this world.

Christians staying since then as “strangers and pilgrims” in the city of man. (See. 1 Pt 2,11). S. Augustinus will be to clarify, through the doctrine of two cities, the relationship between membership in human community and sequela Christi: the Civitas Dei and the Civitas homini, opposite, but not conflicting, in hoc saecula.

This image of the two cities is crystallized in Rome: the Eternal City will be an expression of a conflict, that between the new Babylon – home of disorder, chaos, the Antichrist – and the new Jerusalem, the Universal Church, the heaven, the patria beata.

Just from Book X of De Civitate Dei we can trace a genealogy of the city. From Cain and Abel to the martyr, as mediator and life-giving of urban medieval centre, ordered from the new worship’s places. Writes Peter Brown: “The Mediterranean Christian and its eastern and northwestern foothills came to be dotted loci clearly indicated where they met the sky and earth. The shrine contains a tomb, or, more often, a relic in the form of fragments, was often called simply ‘the place’ loca sanctorum, O to ος”( P. Brown, The cult of the Saints. Its rise and functcion in Latin Christianity, University of Chicago Press, 1980.)

Thus, the transition from pagan to Christian worship is dedicated to adaptation to local conditions. In particular, for urban areas, we can speak about a “mythical-ritual graft” of Christian foundation upon the pagan; of “political achievement” of the extra-urban areas characterized by religious superstition, “process of acculturation” – which includes a number of stations intermediate, which lasts for centuries, and which is marked by more than direct confrontation with paganism, the demystification through evangelization.

- Icon

In a massive production of paintings and images, the cycle of Carpaccio at the Scuola di San Giorgio Schiavoni in Venice, is the occasion for a reflection on the anthropological and theological-political figure of the Holy Knight in battle with the dragon on the foundations of space, in his sense of ritual, political and cultural. Example of the sixteenth century, the large canvases of St. George is a model of representation plans.

The series of paintings – made between 1502 and 1507 – includes, in addition to the well known panel of

St. George fighting the dragon (Fig. 1), and

he Triumph of St. George (Fig. 2)

The baptism of Selenitis (Fig. 3),

St. Tryphon tames the basilisk (Fig. 4),

St. Jerome and the lion in the monastery (Fig. 5),

The funeral of St. Jerome (Fig. 6),

The Calling of St. Matthew (fig. 7),

The Agony in the Garden (Fig. 8) and

St. Augustine’s vision (Fig. 9).

The story of George is directly inspired by medieval hagiographical texts of the martyrs, especially by the Passiones (around the year 1000), the records of the Acta Sanctorum, and especially the story of the Legenda Aurea by Jacopo da Varagine (1293). The epic of Holy Martyr on horseback in the act of defeating the dragon and saving the girl, with the fortified town standing in the background, is a recurring theme since the ancient iconographic applicant.

Over time and places, many similarities are found in the iconography of Saint Micheal (its begin in Gargano, south of Italy, then that spread throughout Europe), St Mercurial (or St. Mercurius, of oriental origin), Saint Theodorus (as is documented in the same Acta Sanctorum) and going backward, the legend of St. George could recall similar images in the Egyptian cosmogonythe solar god Horus in the shape of a knight’s head hawk while stabbing a crocodile, a symbol, like the dragon devil, the destructive energies of chaos.

This figure connected to chaos, undifferentiated sea is present in many stories of origin. The dragon, the crocodile, depicting the sea monster, in the cosmogony of Phoenician origin, the enemy that the deity can repel the abyss during creation. The fight with the dragon, the depiction of evil, brings us back to biblical themes, Egyptian and Mesopotamian, and before that, but it is an image that we find, moreover, also in sagas and Indian and Chinese cosmologies is for this reason that ‘ icon of Saint George and the Dragon speaks of man, and more specifically of human culture, not just of some traditions and devotions, scattered randomly in various parts of the world. The two canvases of St. George and St. Tryphon are elongated, as if to emphasize the character of the epic story that is going to tell: the first “step” of reading is described.

- Violent foundation

The desolate landscape, symbolizing a space not treated, undifferentiated, marks the morphology of an intra and extra Moenia, a determinatio negatio, in Baruch Spinoza’s definition. ( B. Spinoza, Epistola L (edited by C. Gebhardt): “Quia ergo figura non aliud, quam determinatio, et determinatio negatio est; non poterit, ut dictum, aliud quid, quam negatio, esse”. Every thing because of its existence is a negation of something else, writes the philosopher. Equally, the dimension of intra moenia exists as a negation of extra moenia.)

The work of the man on himself, this slow dressage described by Nietzsche in Zur Genealogie der Moral, comes here by a spatial form: the founding of the city, its places bearers of meaning, its lines, its boundaries and walls. A defined space, determined through dialectical oppositions: inside-out, order-chaos, sacred-profane, differentiated-undifferentiated. An absolute negation, saving, exclusive, definitive. Interior space exists only differing from the outside. As mentioned, the outdoors and nature areas in the strict sense, not reached, namely, no civilization, nor any Zivilitation process.

Our culture, represented in the image of the bridge, it is summarized in this figure. George, we have seen, Saint, martyr and soldier. But his name means “farmer”. A farmer in arms to defend the faith. Or, a soldier of Christ, cleric devoted to the cultivation of fields. Culture comes from colere, same root of religion and culture: the act of defining the ground, creating an enclosed space, bounded, a boundary sacred. And ‘here we find the original relationship between employment and demarcation of land, religious rituals and birth culture. Following Carl Schmitt, “the creation of a primordial nomos, a law, but also a well-defined spatial location, with their own cults and rites: this is the first meaning of culture”. A culture that has had, “needs its martyrdoms”. The morphology of the area brings us so close to the triple figure commemorated in George, the farmer’s myth of the soldier of God, bearer of the three fundamental aspects of our culture, presented emblem. Is well known, of course, the theory by George Dumézil, that the institutions of the Indo-European civilization can be summarized into three major functions: Jupiter, the priest and the saint; Mars, the warrior, and Quirinus, the manufacturer. Dumézil writes: “The main elements and gears of the world and society are broken down into three areas that are harmoniously related, in descending order of dignity, sovereignty with its magical aspects and legal ceiling in a kind of expression of the sacred, the physical strength and value, whose most visible manifestation is the war victory, fertility and prosperity, with all sorts of conditions and consequences, almost always meticulously analyzed and represented by a large number of related but different deities, including one or the other by enumerating briefly describe the divine worth of formula. The grouping Jupiter Mars Quirinus, with nuances peculiar to Rome, corresponds to the lists prototypical observable in Scandinavia as in Vedic India and predictable.” The Holy Knight puts them together in one person, articulating with its image as a composite expression combat with spear and shield, protect the ritual function and production, the “three needs that are everywhere the essential: the power and sacred knowledge, the attack and defences, nutrition and well-being for all”. Read more here

- The secret of the old city: a quest for the symbolism in the structure of ‘s-Hertogenbosch

‘s-Hertogenbosch is eight hundred years old. It is a beautiful city, intensely alive and resilient . The city is one of the most fascinating in our country and is one of the coolest that the past has left us. There is a great charm in the special and friendly atmosphere that hangs around the people of ‘s-Hertogenbosch and their city. Over the last twenty-five years it has become apparent that the population is prepared to stand up for the preservation of its beauty and character.