- Sun Dance of the Native Spirits

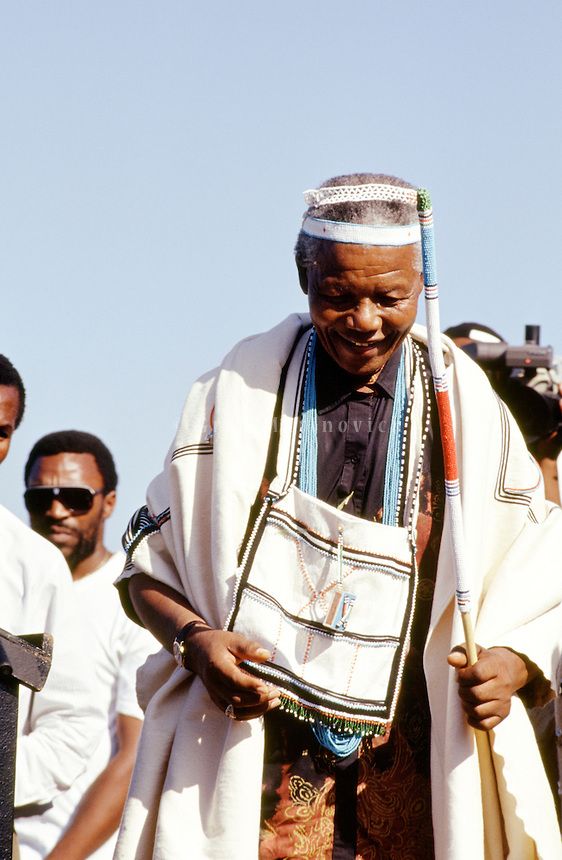

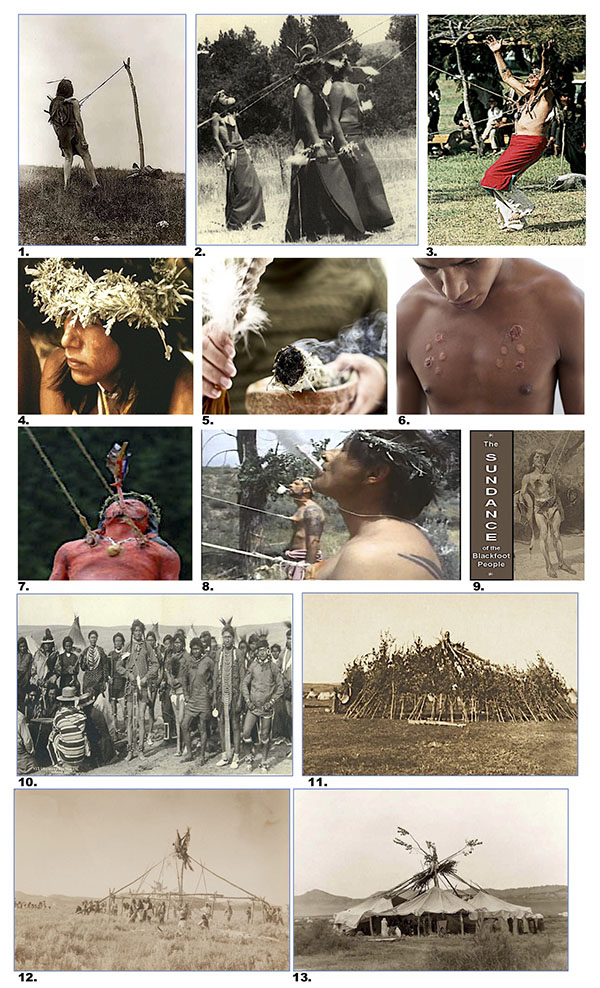

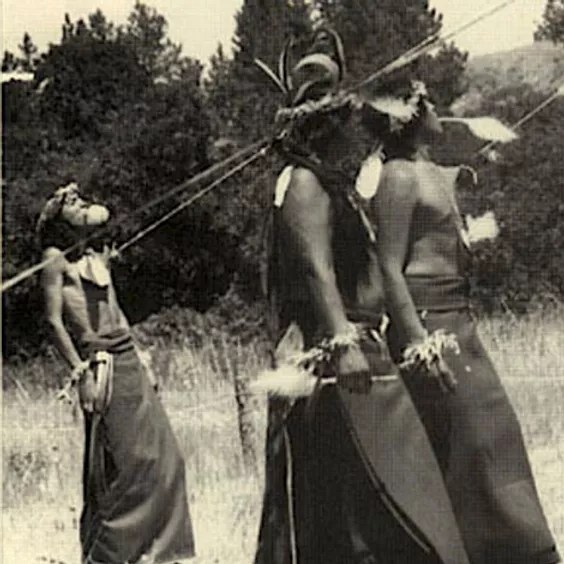

The Sun Dance is the most sacred ritual of Plains Indians, a ceremony of renewal and cleansing for the tribe and the earth. Primarily male dancers—but on rare occasions women too—perform this ritual of regeneration, healing and self-sacrifice for the good of one’s family and tribe. But, in some tribes, such as the Blackfeet, the ceremony is led by a medicine woman. It has been practiced primarily by tribes in the Upper Plains and Rocky Mountain, especially the Arapaho, Arikara, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Crow, Gros Ventre, Hidatsa, Sioux, Plains Cree, Plains Ojibway, Omaha, Ponca, Ute, Shoshone, Kiowa, and Blackfoot tribes.

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by some Native Americans and Indigenous peoples in Canada, primarily those of the Plains cultures. It usually involves the community gathering together to pray for healing. Individuals make personal sacrifices on behalf of the community See more here.

Usually the ceremony was practiced at the summer solstice, the time of longest daylight and lasts for four to eight days. Typically, the Sun Dance is a grueling ordeal, that includes a spiritual and physical test of pain and sacrifice. This ritual usually—but not always—involves piercing rawhide thongs through the skin and flesh of a dancer’s chest with wooden or bone skewers. The thongs are tied to the skewers then connected to the central pole of the lodge. The Sun Dancers dance around the pole leaning back to allow the thongs to pull their pierced flesh. The dancers do this for hours until the skewered flesh finally rips. The Sun Dance is also a rite of passage to manhood.

Sundance – preparation:

The dance is practiced differently by each tribe, but basic similarities are shared by most rituals. In some instances, the Sun Dance was a private experience involving just one or a few individuals. But many tribes adopted larger rituals that involved the whole tribes or sometimes many tribes gathered to celebrate the Sun Dance together. Lodges or open frames built of trees, rawhide or brush are prepared with a central pole at the center.

The Ultimate Ritual of Pain, Renewal & Sacrifice

Though the dance is practiced differently by different tribes, the Eagle serves as a central symbol in the dance, helping bring body and spirit together in harmony, as does the buffalo, for its essential role in Plains Indian food, clothing, and shelter. Sometimes an eagle’s nest or eagle would be mounted at the top of the center pole. Holy men might also place a dried buffalo penis at the top of the pole to give the dancers virility. And buffalo skulls were placed at the perimeter of the lodge to honor their power and courage. (Some dancers choose to have their flesh pierced through their backs and the rawhide ropes from the skewers are attached to the heavy buffalo skulls. Then the dancers dance on rocks and brush as they drag the heavy skulls. This usually takes longer to rip their flesh.

Buffalo–Tatanka

Tatanka are held in high regard by Native Americans. The tatanka gave up its own flesh and life to provide everything for the people. For Native Americans, the tatanka is a true relative, making life possible for them. Because of their importance, a buffalo symbol or skull is present in all sacred Lakóta rituals. The tatanka represent generosity and self-sacrifice. According to the Lakóta, to give what you have to others is one of the most highly respected way of behaving.

Dancers also blow a whistle made from the wing bone of an eagle that makes the sound of an eagle cry. The whistle is painted with colored dots and lines to represent the keen and precise perception of the eagle. There is also a beautiful eagle feather attached to the end of the whistle that blows back and forth to represent the breath of life.

In Native culture, the wanblí is considered the strongest and bravest of all birds. For this reason, its feathers symbolize what is highest, bravest, strongest, and holiest. When a feather falls to the earth, it is believed to carry all of the bird’s energy, and it is perceived as a gift from the sky, the sea, and the trees. Feathers may arrive unexpectedly but not without a purpose.

Each type of feather represents something different. The wanblí’s feather, however, is one of the most esteemed. An wanblí’s feathers are given to another in honor, and the feathers are displayed with dignity and pride.

Many tribes smoke sage and burn smudge pots of sage, which is believed to conjure spirits and help the dancers. Some tribes also wear wreaths of sage on their heads and wrists. Ancient dances and songs passed down through many generations are offered accompanied by traditional drums, smudge pots of sage are burned over a sacred fire.

The entire tribe prepares for a year before the ceremony and the dancers fast for many days in the open before the dance. The Sun Dance ceremony involves all the tribe. Family members and friends (only Native people are allowed to attend) gather in the surrounding camp to chant, sing and pray in support of the dancers.

If sun dancers have not released themselves from their bloody tethers by sundown, holy men remove the skewers and reverse the piercings to help rip the flesh. In the 1918 definitive book, “The Sundance of the Blackfoot People,” by leading American anthropologist Clark Wissler, he states: “When all thongs are torn out, the lacerated flesh is cut off as an offering to the sun… The author has seen some men extremely scarred from repeated Sun Dance ceremonies…The offering of flesh is called the Blood Sun Dance.” Exhausted dancers would be cared for afterward in a medicine lodge, where holy men and women sung and prayed above them.

The ceremony was extremely arduous and not without its risks. Clark Wissler also wrote: “It is said that all who take this ceremony die in a few years, because it is equivalent to giving one’s self to the sun. Hence, the sun takes them for its own.”

In 1883, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior and the Bureau of Indian Affairs criminalized the Sun Dance and other sacred religious ceremonies in an effort to discourage indigenous practices and enculturate Native Americans into white society. The prohibition was renewed in 1904 and remained illegal until 1934 when Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s new administration reversed the decision. During the fifty years the Sun Dance was prohibited, many native tribes defied the law and continued to perform their most sacred dance, usually as part of Fourth of July celebrations!

Read hereTHE SPIRITUAL LEGACY OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

Read here : American Indian Religious Traditions

Native Spirit and The Sun Dance Way Home Page

Eagle (heraldry)

The eagle is used in heraldry as a charge, as a supporter, and as a crest. Heraldic eagles can be found throughout world history like in the Achaemenid Empire or in the present Republic of Indonesia. The European post-classical symbolism of the heraldic eagle is connected with the Roman Empire on one hand (especially in the case of the double-headed eagle), and with Saint John the Evangelist on the other.

A golden eagle was often used on the banner of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia. Eagle (or the related royal bird vareghna) symbolized khvarenah (the God-given glory), and the Achaemenid family was associated with eagle (according to legend, Achaemenes was raised by an eagle). The local rulers of Persis in the Seleucid and Parthian eras (3rd-2nd centuries BC) sometimes used an eagle as the finial of their banner. Parthians and Armenians used eagle banners, too.[1]

In Europe the iconography of the heraldic eagle, as with other heraldic beasts, is inherited from early medieval tradition. It rests on a dual symbolism: On one hand it was seen as a symbol of the Roman Empire (the Roman Eagle had been introduced as the standardised emblem of the Roman legions under consul Gaius Marius in 102 BC); on the other hand, the eagle in early medieval iconography represented Saint John the Evangelist, ultimately based on the tradition of the four living creatures in Ezekiel. Read more here

- Falconry as a Transmutative Art: Dante, Frederick II, and Islam

The imperial eagle – notably, in the form handed down by the Romans to later generations of European rulers – is the hypostasis of an absolute power conceived as “naturally” divine in origin. In contrast, the tamed falcon, at rest on the emperor’s fist or being offered to him by his falconers, became for Frederick II the emblem of an acquired form of wisdom – of a nobility, that is, which must be educated so that its inborn aggressiveness may be restrained and redeployed under the superior command of reason. The falconer thereby becomes the image of the ideal sovereign, he who succeeds in controlling the instinctual aggressiveness of humankind by way of his “taming power.” He is at one and the same time the self-aware and responsible repository of natural law and the guar- antor of positive law, that is, of justice. The study and practice of falconry were therefore for Frederick II the best and noblest ways for the sovereign to deepen his understanding of the laws of the natural and of the human realm; to him they were indispensable tools in his honorably dispatching his mission as universal sovereign….

….If the objective of the Commedia is to save humankind from itself and principally from its self-imposed rapaciousness, then we can usefully ask ourselves which figurative means Dante could call upon to evoke a process of taming and conversion that by its very nature aims at transmuting the individual’s instinctive ego-grasping into an artfully acquired – but nevertheless also gracefully received – form of absolute surrender and self-sacrifice to the highest manifestation of selflessness and boundless love.

How are we to visualize the very nature of a learning process that must be experiential if it is to become effective? Such is, after all, the goal of the Commedia as a whole – in direct opposition, that is, to the treacherous attempts at rational grappling with reality, which leave human pride misleadingly in charge of transcendent affairs. While in our postmodern world of con- cept-based existence there seems to be little or nothing to call upon in order to suggest such a salvific becoming, I hope to have shown persuasively that Dante saw in falconry the art most apt to express that process of surrender and taming of an individual’s own nature, in the form of a return to that very “hand” on whose universal fist the whole world is unknowingly perched. For Dante, no art better than falconry could convey the sense of that sacrificial inner transmutation necessary for human consciousness to awaken to the vision of itself as a pure reflection of the transcendental source of all-encompassing love.

No other art could as powerfully express the potential for universal salvation inscribed within a process meant to make human consciousness cognizant of its own divine origin – of its own participation in, and belonging to the very substance offered by the falconer to the falcon as its only rightful meal, as that “bread of angels” already evoked in the Convivio: purely celestial food, on which life itself unsuspectingly keeps feeding. …. Read the complete paper Falconry as a Transmutative Art: Dante, Frederick II, and Islam

see also: Raptor and human – falconry and bird symbolism throughout the millennia on a global scale

———————————————————-

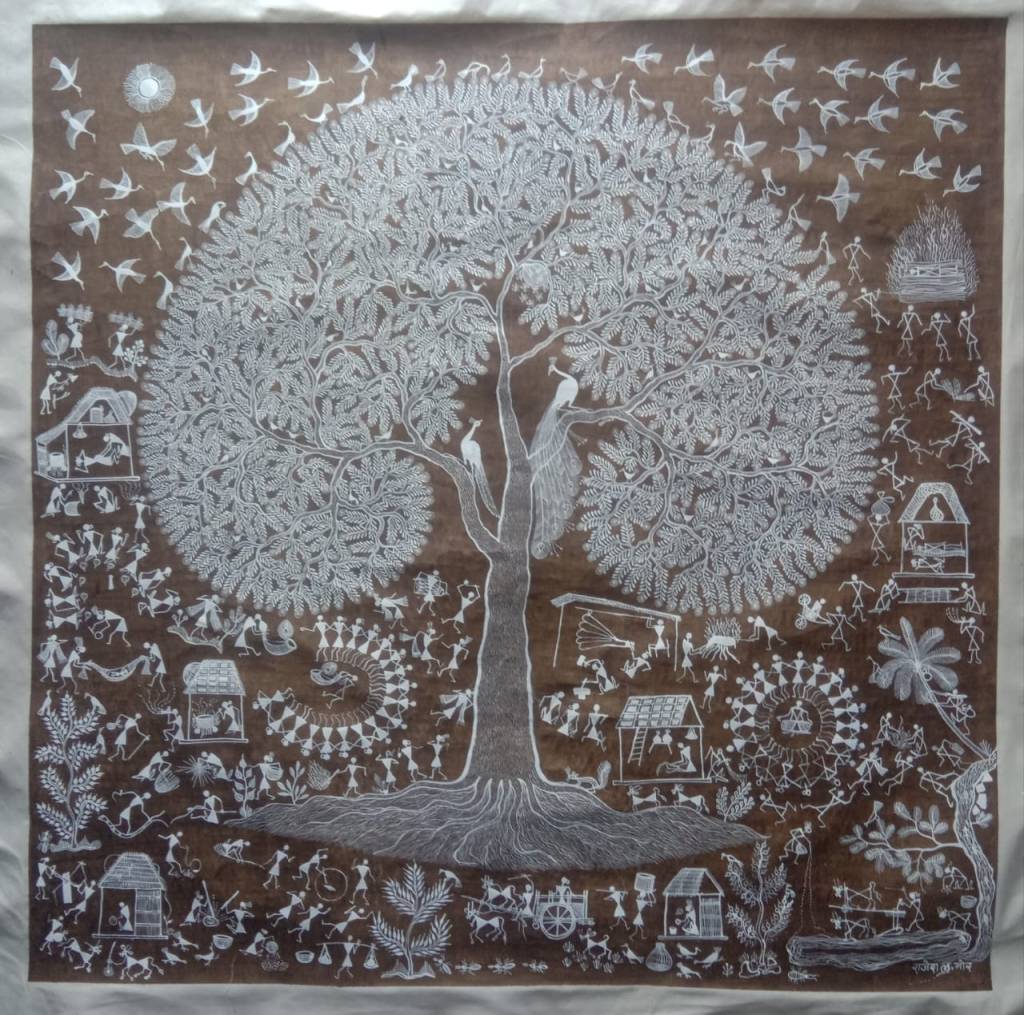

HISTORY OF THE WARLIS

The Warlis are an aboriginal tribe living at the foothills of the Sahyadris in western India.

Warlis were hunters and gatherers living in the forest. With time, they were forced to settle down at the base of the hills, and so, they adopted an agro-pastoral lifestyle.

Waral is brushwood which the original settlers had to clear in order to settle down.

Warul also refers to the brushwood used to burn on the fields as Rab.

This could be the origin of the name of their tribe- Warli

n the book The Painted World of the Warlis Yashodhara Dalmia claimed that the Warli carry on a tradition stretching back to 2500 or 3000 BCE. Their mural paintings are similar to those done between 500 and 10,000 BCE in the Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka, in Madhya Pradesh.

Their extremely rudimentary wall paintings use a very basic graphic vocabulary: a circle, a triangle and a square. Their paintings were monosyllabic. The circle and triangle come from their observation of nature, the circle representing the sun and the moon, the triangle derived from mountains and pointed trees. Only the square seems to obey a different logic and seems to be a human invention, indicating a sacred enclosure or a piece of land. So the central motive in each ritual painting is the square, known as the “chauk” or “chaukat”, mostly of two types: Devchauk and Lagnachauk. Inside a Devchauk, we find Palaghata, the mother goddess, symbolizing fertility.[3] Significantly, male gods are unusual among the Warli and are frequently related to spirits which have taken human shape. The central motive in these ritual paintings is surrounded by scenes portraying hunting, fishing and farming, festivals and dances, trees and animals. Human and animal bodies are represented by two triangles joined at the tip; the upper triangle depicts the trunk and the lower triangle the pelvis. Their precarious equilibrium symbolizes the balance of the universe, and of the couple, and has the practical and amusing advantage of animating the bodies.

The pared down pictorial language is matched by a rudimentary technique. The ritual paintings are usually done inside the huts. The walls are made of a mixture of branches, earth and cow dung, making a Red Ochre background for the wall paintings. The Warli use only white for their paintings. Their white pigment is a mixture of rice paste and water with gum as a binding. They use a bamboo stick chewed at the end to make it as supple as a paintbrush. The wall paintings are done only for special occasions such as weddings or harvests. The lack of regular artistic activity explains the very crude style of their paintings, which were the preserve of the womenfolk until the late 1970s. But in the 1970s this ritual art took a radical turn, when Jivya Soma Mashe and his son Balu Mashe started to paint, not for any special ritual, but because of his artistic pursuits. Warli painting also featured in Coca-Cola’s ‘Come home on Diwali’ ad campaign in 2010 was a tribute to the spirit of India’s youth and a recognition of the distinct lifestyle of the Warli tribe of Western India.[4]

Tribal Cultural Intellectual Property

Warli Painting is the cultural intellectual property of the tribal community. Today, there is an urgent need for preserving this traditional knowledge in tribal communities across the globe. Understanding the need for intellectual property rights, the tribal non-profit Organisation “Adivasi Yuva Seva Sangh” initiated efforts to start a registration process in 2011. Now, Warli Painting is registered with a Geographical Indication under the intellectual property rights act. With the use of technology and the concept of social entrepreneurship, Tribals established the Warli Art Foundation, a non-profit company dedicated to Warli art and related activities.

Culture

Warli legends say that the Gods went to the potter fly or Gungheri Raja to ask for balls of mud to make the earth which was flooded with water. Read here the Mystical World of Warli

Tradition

The Warli Painting tradition in Maharashtra are among the finest examples of the folk style of paintings. The Warli tribe is one of the largest in India, located outside of Mumbai. Despite being close to one of the largest cities in India, the Warli reject much of contemporary culture. Warli paintings of Maharashtra revolve around the marriage of God Palghat.The style of Warli painting was not recognised until the 1970s, even though the tribal style of art is thought to date back as early as 10th century A.D.[1] The Warli culture is centered on the concept of Mother Nature and elements of nature are often focal points depicted in Warli painting. Farming is their main way of life and a large source of food for the tribe. They greatly respect nature and wildlife for the resources that they provide for life.[2] Warli artists use their clay huts as the backdrop for their paintings, similar to how ancient people used cave walls as their canvases.

Jivya Soma Mashe, the artist in Thane district has played a great role in making the Warli paintings more popular. He has been honoured with a number of national and central level awards for his paintings. In the year 2011, he was awarded Padmashree.

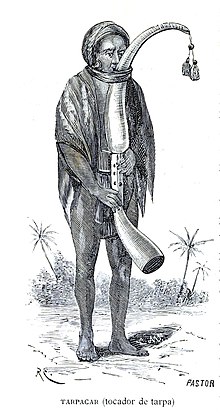

A tarpa player c.1885

These rudimentary wall paintings use a set of basic geometric shapes: a circle, a triangle, and a square. These shapes are symbolic of different elements of nature. The circle and the triangle come from their observation of nature. The circle represents the sun and the moon, while the triangle depicts mountains and conical trees. In contrast, the square renders to be a human invention, indicating a sacred enclosure or a piece of land. The central motif in each ritual painting is the square, known as the “chauk” or “chaukat”, mostly of two types known as Devchauk and Lagnachauk. Inside a Devchauk is usually a depiction of palaghat, the mother goddess, symbolizing fraternity.[3]

Male gods are unusual among the Warli and are frequently related to spirits which have taken human shape. The central motif in the ritual painting is surrounded by scenes portraying hunting, fishing, and farming, and trees and animals. Festivals and dances are common scenes depicted in the ritual paintings. People and animals are represented by two inverse triangles joined at their tips: the upper triangle depicts the torso and the lower triangle the pelvis. Their precarious equilibrium symbolizes the balance of the universe. The representation also has the practical and amusing advantage of animating the bodies. Another main theme of Warli art is the denotation of a triangle that is larger at the top, representing a man; and a triangle which is wider at the bottom, representing a woman.[4][better source needed] Apart from ritualistic paintings, other Warli paintings covered day-to-day activities of the village people.

One of the central aspects depicted in many Warli paintings is the tarpa dance. The tarpa, a trumpet-like instrument, is played in turns by different village men. Men and women entwine their hands and move in a circle around the tarpa player. The dancers then follow him, turning and moving as he turns, never turning their backs to the tarpa. The musician plays two different notes, which direct the head dancer to either move clockwise or counterclockwise. The tarpa player assumes a role similar to that of a snake charmer, and the dancers become the figurative snake. The dancers take a long turn in the audience and try to encircle them for entertainment. The circle formation of the dancers is also said to resemble the circle of life.

Warli painting from Thane district

Materials used

The simple pictorial language of Warli painting is matched by a rudimentary technique. The ritual paintings are usually created on the inside walls of village huts. The walls are made of a mixture of branches, earth and red brick that make a red ochre background for the paintings. The Warli only paint with a white pigment made from a mixture of rice flour and water, with gum as a binder. A bamboo stick is chewed at the end to give it the texture of a paintbrush. Walls are painted only to mark special occasions such as weddings, festivals or harvests. They make it with a sense that it can be seen by future generations.

In contemporary culture

The lack of regular artistic activity explains the traditional tribal sense of style for their paintings. In the 1970s, this ritual art took a radical turn when Jivya Soma Mashe and his son Balu Mashe started to paint. They painted not for ritual purposes, but because of their artistic pursuits. Jivya is known as the modern father of Warli painting. Since the 1970s, Warli painting has moved onto paper and canvas.[5]

Coca-Cola India launched a campaign featuring Warli painting in order to highlight the ancient culture and represent a sense of togetherness. The campaign was called “Come Home on Deepawali” and specifically targeted the modern youth.[6] The campaign included advertising on traditional mass media, combined with radio, the Internet, and out-of-home media.

Traditional knowledge and intellectual property

Warli Painting is traditional knowledge and cultural intellectual property preserved across generations. Understanding the urgent need for intellectual property rights, the tribal non-governmental organization Adivasi Yuva Seva Sangh[7][8] helped to register Warli painting with a geographical indication under the intellectual property rights act.[9] Various efforts are in progress for strengthening sustainable economy of the Warli with social entrepreneurship.[10]

=========================

You are good and i am evil

will You remember my poor soul

I will bestow You an Ave Maria

Ave, Ave Maria, Ave Ave maria

Kill your Dragon

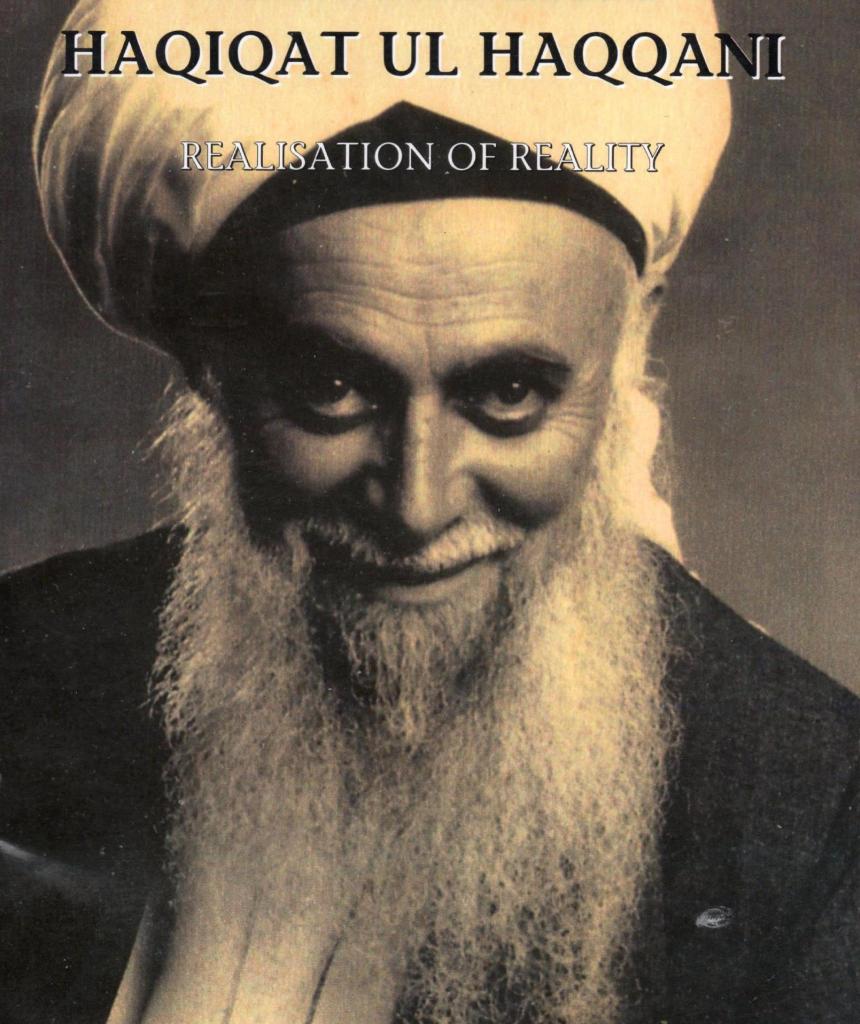

“Our only purpose is to give our love, respect and service to God but if given the opportunity every person would be a pharaoh. His ego would declare itself the highest lord. We must kill the dragon that is our ego and then we will find Allah with us and around us and within us” Sheikh Nazim al Haqqani

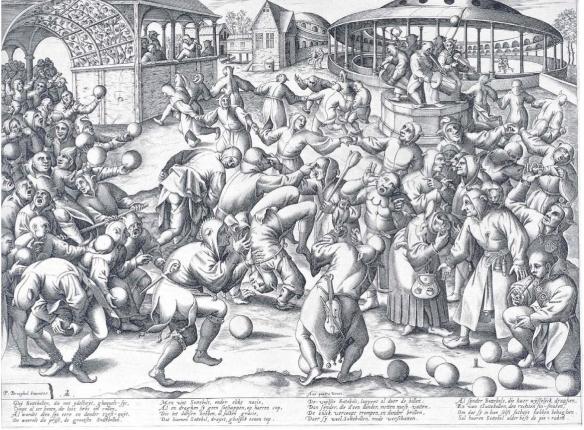

Looking to the Spiritual vertical way, as the Maypole do, gives us an opportunity of discerning an understanding between Non-Virtues and Virtues, developing Spiritual values needed in our times :. Read here: Maypole the Principle of verticality

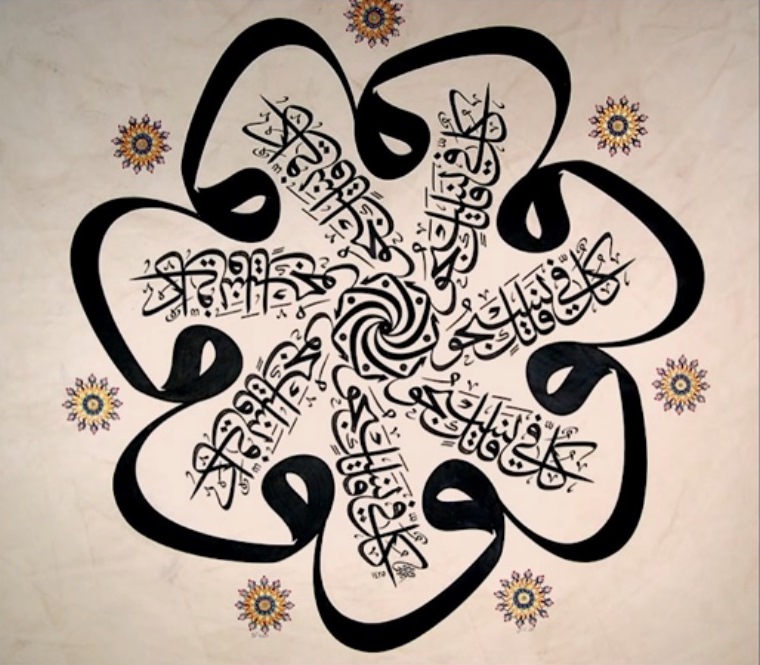

Ash-Shams (Arabic: الشمس, “The Sun”) is the 91st surah of the Qur’an, with 15 ayat or verses.

BY the Sun, and its rising brightness[18]

by the moon when she followeth him

by the day, when it showeth its splendor

by the night, when it covereth him with darkness

by the heaven, and him who built it

by the earth, and him who spread it forth

by the soul, and him who completely formed it

and inspired into the same its faculty of distinguishing, and power of choosing, wickedness and piety: now is he who hath purified the same, happy

but he who hath corrupted the same, is miserable.

1-10 Good and evil

BY the Sun, and its rising brightness[18] by the moon when she followeth himby the day, when it showeth its splendorby the night, when it covereth him with darknessby the heaven, and him who built itby the earth, and him who spread it forthby the soul, and him who completely formed itand inspired into the same its faculty of distinguishing, and power of choosing, wickedness and piety: now is he who hath purified the same, happybut he who hath corrupted the same, is miserable.

The first part deals with three things:-:

1-That just as the sun and the moon, the day and the night, the earth and the sky, are different from each other and contradictory in their effects and results, so are the good and the evil different front each other and contradictory in their effects and results; they are neither alike in their outward appearance nor can they be alike in their results.

2-That God after giving the human self powers of the body, sense and mind has not left it uninformed in the world, but has instilled into his unconscious by means of a natural inspiration the distinction between good and evil, right and wrong, and the sense of the good to be good and of the evil to be evil.

3-That the future of man depends on how by using the powers of discrimination, will and judgement that Allah has endowed him with, he develops the good and suppresses the evil tendencies of the self. If he develops the good inclination and frees his self of the evil inclinations, he will attain to eternal success, and if, on the contrary, he suppresses the good and promotes the evil, he will meet with disappointment and failure. Sahl al-Tustari (d. 896), a Sufi and scholar of the Qur’an, mentions, “By the day when it reveals her [the sun],He said:This means: the light of faith removes the darkness of ignorance and extinguishes the flames of the Fire.[20][21]

Dit delen:

…

The adults of the community build the hut in which the initiates will live for the month of the ceremony. ©Richard Bullock

The adults of the community build the hut in which the initiates will live for the month of the ceremony. ©Richard Bullock