Read here : Islam, the freedom to serve

«We ask to be no-one and nothing,

For, as long as we are someone,

we are not complete.»

Look also : 99 Drops From Endless Mercy Oceans

Read here : Islam, the freedom to serve

«We ask to be no-one and nothing,

For, as long as we are someone,

we are not complete.»

Look also : 99 Drops From Endless Mercy Oceans

Remarks on Evil, Suffering, and the Global Pandemic*

Seyyed Hossein Nasr

*This piece is an edited transcription of Professor Nasr’s keynote address delivered at the conference upon which the present volume is based: In From the Divine to the Human: New Perspectives on Evil, Suffering, and the Global Pandemic, edited by M. Faruque and M. Rustom. London and New York: Routledge, 2023.

The general problem of evil is a subject about which many books have been written for thousands of years and much of great depth has been said already. It also became very critical with the rise of modernism in the sense that a lot of people in the West and even in Western Christianity in general have left religion because they could not answer the question, “If God is good, why is there evil in the world which is created by Him?”

Many variations of this question thus permeate both Western philosophy and Western literature, not to speak of Christian theology. The Islamic perspective on the problem of evil is in general very different from what one finds in the mainstream in the West. You cannot find Muslims who turn against God because of the presence of evil in the world; and the few who do are Westernized Muslims who think that to be fully modernized and Westernized, one should also have the same “pains” in facing the world from which many Westerners suffer. Such Muslims do not turn to their own tradition’s intellectual and spiritual resources to deal with this issue, such as the remarkable and also diversified discussions in the writings of al-Ghazālī, Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī, Ibn Sīnā, Ibn ʿArabī, and others.

These authors always deal with the problem of evil on the basis of their complete acceptance that God is real and that He is good. Thus, their attempts to solve the problem of the existence of evil did not affect their belief in the reality of God. With these words in mind, allow me to now delve into this very contentious and difficult issue.

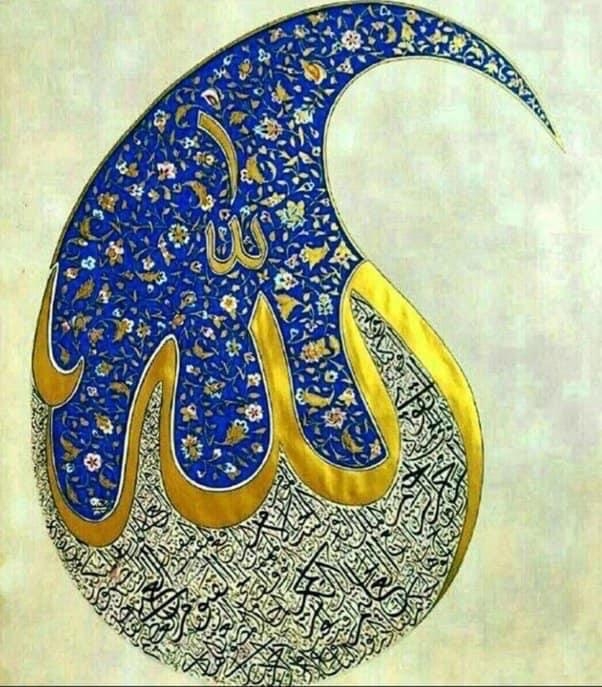

First of all, let us ask the question, “What is evil?” Let me point out that in the Islamic tradition, a common word for “evil” is the Arabic term qubḥ; the word that is opposed to it is ḥusn or “goodness.” But these terms, moreover, also mean “ugliness” and “beauty,” respectively. Thus, from the Islamic point of view, you could say that goodness is that which is beautiful and evil is that which is ugly.

The dualism of pre-Islamic Iranian religions such as Zoroastrianism, that is, dualism between good and evil as two independent realities, between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman, works perfectly well on the ethical and practical level, but not so on the metaphysical level, for there cannot be two Divine Principles. This explains why there have been certain metaphysicians and Sufis in the Islamic world who have gone so far as to say that there is no evil in the ontological sense. Rūmī, for example, speaks about this issue and defends it; but one must understand what he means. Since the Divine, the Absolute (al-muṭlaq), who is also the All-Good, is ultimately all that there is and there is no evil in It, evil as such does not exist. This is what Rūmī and others mean when they say there is no evil. In the Absolute, there is only the Absolute; there is nothing else. A famous Hadith tells us that “God was and there was nothing with Him” (kāna Allāh wa-mā kāna maʿahu shayʾun). And to this saying the Islamic metaphysicians add, “And it is now as it was” (wa’l-ān kamā kān ). So evil does not have the same ontological basis as does goodness. From the metaphysical point of view, there is therefore no equivalent ontological juxtaposition between good and evil.

Nevertheless, if there is no evil per se in the absolute sense, that does not negate the fact that evil is real on the level of relative existence, which is that of this world. Otherwise, the Quran would not affirm the reality of some form of evil on practically every other page, such as when it warns man not to perform evil acts. Evil is as real as the shadow under a tree beneath which a person sits in order to protect himself from the sun. This shadow does have an ontological reality, but it is essentially the absence of light. On the plane of the relative, evil is as real as we are as fallen human beings; but on the level of the Absolute, it is as unreal as we are.

Now, there is also this point to add about which the Sufis have always spoken, and which is the most important way to understand why there is evil. If we conceive of God as Light—after all He Himself says that He is the “Light of the heavens and the earth” (Q 24:35)—and we conceive of Him as the Light of lights (nūr al-anwār), as we move away from It, the illumination of this Light becomes less and less, and darkness becomes more and more pervading until we get so far from the source of Light that there is only darkness. But darkness is not a substance, as is light. Darkness is simply the absence of light. Evil is seen in Islamic inner teachings in this way. Only God is Good, but He also creates. Creation implies separation—separation from the Source—and that separation means the gradual weakening of the Light of the Divine Sun. The crystallization of this separation is what we call “evil.” To understand in depth this one principle is to understand everything about the root of the existence of evil in this world of separative existence.

Ultimately, evil is the result of separation from the good: Dante said so beautifully in the Divine Comedy that evil is separation from God. On the human plane, being the ordinary human beings that we are, we live in separation from God, which is why evil is as real as we are. If there were no separation from God, there would be no creation and no evil. Creation implies limitation—limitation because of separation from that which is Absolute and Infinite, hence limitless. From this separation there arises evil in various forms.

We must at the same time be careful not to trivialize evil, which is one of the great errors of modernism. It not only relativizes both good and evil in denying the Absolute as well as the relatively absolute, but often denies the ultimate significance of both by relating them simply to social norms and the like; that is, rather than denying evil on the level of the Absolute, this tendency in question seeks to deny it on the level of the relative. Yet denying evil on the level of relativity is like absolutizing the relative, which is of course the cardinal sin of modern atheism from a theological point of view and an error from the metaphysical point of view.

I have in mind here those people who say that everything is relative, except of course their statement that everything is relative. How remarkable it is that Islamic thought, even before modern times, was fully aware of the problem of relativizing the relative which derives its reality from the One who alone is Real, and also the problem of confusing the relative with the Absolute. This view is totally different from what some sages such as Frithjof Schuon have called, as just mentioned, the “relatively absolute,” namely the manifestation of the Absolute in a relative way that retains something of that absoluteness in it. An example of this reality would be the Quran itself. There is something absolute about it as revelation coming from God, the Absolute. There are no other books that compare to it; yet the Quran is not the Absolute as such, but a reality that eflects the Divine Reality and the Will of God. Only God is the Absolute.

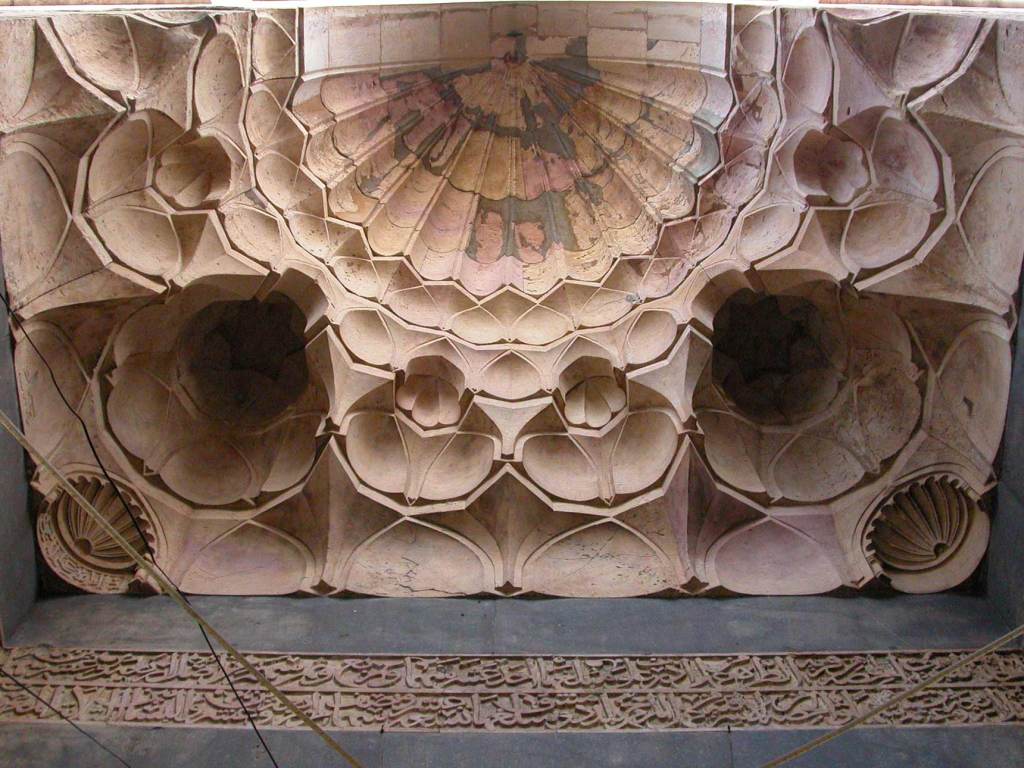

Allow me to come back to the question of beauty and ugliness, for it is not a superficial matter. One of the most remarkable features of traditional civilizations is the presence of so much beauty and so little ugliness. The stable in which Christ was born was much more beautiful than any one of these modern churches built on M street in Washington, DC; there is no doubt about it. That is why we go and visit those old sites which were simple, even stables where horses or animals were kept.

This idea of the centrality of beauty was especially strong in Islam, where you have the famous Hadith, “God is beautiful, and He loves beauty.”So our whole attachment to God involves God’s beauty and also love. If you love God, you must love what God loves, and thus you must love beauty. Islamic civilization was remarkably successful in creating things of beauty, from the carpets on which people sat to the minarets from which the call to prayer was made, and nearly all the objects, buildings, and surfaces in between.

From the Islamic point of view aesthetics and ethics are not separated from each other; although evil has to do with ethics, whereas ugliness has to do with aesthetics, the two are closely related. This is totally different from the view that is now prevalent in many religious circles in the West and even to some extent in some parts of the Islamic world where Muslims have done a good job in matching Westerners in building ugly mosques, not to speak of other elements from inte-rior design to everyday utensils. Traditionally, goodness was also associated with the beauty of the soul and evil with its ugliness. Even in English when one says, “I did something ugly” or “This was an ugly act,” it refers to an evil act and not a

good one.

A comment is also in order concerning our responsibility before evil. In Islam, we are always responsible for our actions. If something happens for which we are not responsible, we will not be judged by God for its consequences. The question of responsibility involves not only the act itself but also the conditions in which the act is performed. What is evil? It is what we know to be evil and nevertheless commit with our free will. If we had no free will, we could not commit evil. So the question of responsibility in relation to evil is very important, and this fact necessitates saying something about knowledge. Without knowledge, there cannot really be evil; we have to know what is good and bad before being responsible for our actions, which is why all sacred scriptures emphasize this point so much. We have to know what God wants of us. Without this knowledge, one would be innocent; ignorance is innocence in this sense. However, we are also required to try to not be ignorant, which takes us back to responsibility.

I now turn to the question of suffering. One might say that suffering comes ultimately from separation from God. When we were in Paradise, close to God, we did not suffer; suffering comes from separation from who we really are, from our fiṭra or primordial nature. We have fallen on earth and have fallen away from who we are really, but nevertheless we carry something of that reality within us.

The whole of the religious life is based on us seeking to return to the real us, to how God created us. Suffering thus has to do with a loss of identity in a sense, more than anything else. That is the height of it. With it comes all other forms of suffering human beings experience: physical pain, psychological pain, economic suffering, wars, pestilence, etc. There is, however, a very important difference in the use and interpretation of this universal human experience in the religious life, and this reality is important to mention these days because, despite the prevalence of secularism for many Westerners, Christianity is still the dominant religion and

Christian ethics and ideals are still prevalent even among secularists.

Christ suffered in a way that the Prophet of Islam did not. The Prophet also suffered, but Christ suffered on the cross. He suffered excruciating pain, and the image of Christ in the Christian mind—the cross being the sacred symbol of Christianity— is that of Christ suffering. Has one ever seen a picture of Christ laughing on the cross? The famous paintings of Velazquez, Michelangelo, or even Giotto are scenes of Christ’s life where Christ is smiling. But on the cross He is suffering; He is in pain, sometimes with His head down. And so, suffering plays a special religious role in Christianity that it does not in Islam. Moreover, Buddhism shares this perspective to some extent with Christianity, paying specific attention to the fact that this world is characterized by suffering, although images of the Buddha himself are characterized by the state of bliss rather than pain. For Muslims, therefore, suffering does not pose the same theological significance as it does for Christians, although it is considered to be a part of human life.

Some people suffer more, some less; some people know why they suffer, some do not; and so on. In any case, we must remember that ordinary human beings only know so much of the trajectory of their lives—they do not really know what came before and they do not know what is going to come after. We cannot judge our relationship with God and His Presence or the lack thereof in our lives only in relation to what we remember of the acts that we have performed or not performed, since this type of awareness concerns only a small part of the trajectory of our lives that extends to before our coming into this world and after our departing from it.

When Muslims think of the Prophet, they think of all the difficulties he had, all the problems that he and his Companions faced. But they do not identify his life essentially with suffering. The Prophet came to bring knowledge of the One (lā ilāha illā’Llāh), as he said, “Say, ‘There is no god but God,’ and be saved.” That is it.

That was his message. He came to the world to reveal that basic truth. Everything else in Islam comes from this one teaching concerning the reality of God and our relation to Him.

Spiritually speaking, suffering should always be an occasion for us to draw closer to God. The word dard in Persian, which can mean “pain” or “suffering,” was often used by Sufis in a positive sense. There are many Sufi texts about this matter, and there is even a famous Sufi poet of India whose takhalluṣ or penname was Dard. Suffering should always have a spiritual element connected to it. We should accept pain and suffering as part of our destiny and should not rebel against Heaven because we suffer and question God by asking why if one is good do bad things happen to him or her, and the like. This type of attitude is prevalent in the modern world, but it is an error from the Islamic point of view. God knows best— He has created us. Suffering should bring us closer to Him.

This brings me to the final issue, namely the pandemic. The pandemic is a very concrete lesson about what I have already discussed. From the human point of view, yes the pandemic is evil. But from the point of view of the viruses that created the pandemic, it is not evil at all because it is the expansion of their kingdom. And I hate to say this, but with respect to the preservation of the natural environment, the pandemic has not been negative. Yes, we are sad that several million people have died. Yet we should also look at how much waste several

million people can create over a period of two years. It is very tragic to say it, but we human beings are living in such a way that our very existence is a danger to the continuation of life on earth, and the pandemic should first and foremost be a reminder to us that we are not the lords of nature. Nature can play the same game, and little viruses that mean nothing to you can outwit you and rob you years of a healthy life, leaving even the best scientists unable to do something about them. In helping us to realize our limited power over nature, the experience of the pandemic should also remove some of the hubris of the modern natural sciences which has percolated into the whole of modern society. It should bring about a sense of humility. This triumphalism which has been wed to modern science since before the time of Galileo in the early 17th century needs to be changed, as it is very dangerous for human life and the future of the earth.

With this humility should come an awareness of how precious life is, of how we usually take everything for granted. Three years ago, when we walked in the street we did not constantly think about viruses, wear masks, wash our hands, wipe down surfaces, etc. The suddenness of the pandemic alone should make us more humble and should make us realize that life is not to be taken for granted. It is one of the great sins of modern man that he takes existence itself and all the blessings that God has given to him for granted, thinking that it is his right to exist and have blessings, and always wanting more. He should rather ask himself these questions:“Did I create myself?” No. “Can I make my own liver?” No. “What did I do that makes me who I am?” Nothing. Yes, he eats to make his body grow; but even when he eats, he does not know how his body grows. The cells in his body that are absorbing the food, applying the oxygen, and so forth are not under his control; they are performing their own functions according to their nature. These observations are important to keep in mind in order to bring about within us an appreciation of the preciousness of life and along with it a sense of inwardness. You cannot have happiness by relying only on outward factors, as the outward world around you might crumble at any moment.

We have to find our joy within ourselves. “The Kingdom of God is within you,” Christ said, and the Prophet said, qalb al-muʾmin ʿarsh al-Raḥmān, “The heart of the faithful is the Throne of the All-Merciful.”

Finally, the experience of the pandemic should bring about in us greater tawakkul, greater reliance upon God and less reliance upon the absoluteness of human will and capability. This is not to say that we should not rely on the gifts which God has given to us, because the fact that we can do something itself comes from God. I use the Arabic term tawakkul, the idea of total reliance upon God, because it is so important in Islam. What is negative, what belongs to the shadows, namely the evils of the pandemic, can also bring about some good. There is nothing in life that happens from which one cannot draw a positive lesson, and happy are those whom God allows to do so.

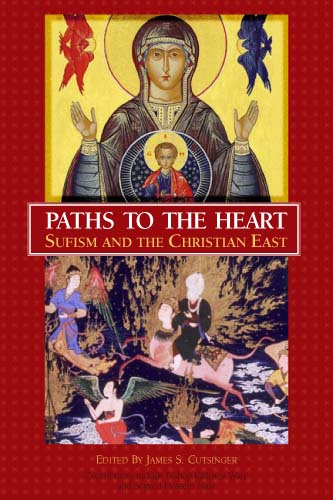

For an exposition of this Hadith, see Seyyed Hossein Nasr, “The Heart of the Faithful Is the Throne of the All-Merciful,” in Paths to the Heart: Sufism and the Christian East, ed. James Cutsinger (Bloom- ington: World Wisdom, 2004), 32–45.

Look also: The Prayer of the Heart in Hesychasm and Sufism

Alan Ereira talks about the wisdom of the Kogi Indians and an important new UNESCO project in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in Colombia – From Beshara magazine

In 1991, in the last edition of the original Beshara Magazine, we published an article by journalist Alan Ereira about an extraordinary people living in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in the north of Colombia (to read it click here). The descendants of a great civilisation which fled to the hills as the Spanish took over their lands, the Kogi had lived for 400 years in isolation, led by a class of priests called ’the mamas’. They asked Alan to help them make a film in order to communicate with us – ‘the younger brother’ – and warn us about the ecological destruction we are wreaking upon the earth. The result was a BBC documentary and a book entitled ‘The Heart of the World’. Thirty years later, the Kogi are making another attempt to communicate their wisdom, this time through a regeneration project, Munekan Masha, under the auspices of the UNESCO Bridges initiative. Alan talked to Jane Clark and Richard Gault about what it involves and the unified vision which underlies it. At the end of the article we include a video of a recent talk he gave on the project which you might want to watch before reading the interview.

Video: Kogi Knowledge: Learning Planet Festival, 27 January 2023. Duration: 54 mins

Jane: It is about 30 years since we did an article on the Kogi in the last printed edition of Beshara Magazine and you made your first film about the Kogi for the BBC, From the Heart of the World.[1] So can we begin by doing a little bit of catching up. For instance, since we last spoke you have set up a charitable foundation, the Tairona Heritage Trust [/], which has enabled the Kogi to preserve their culture, and in particular, acquire more land.

Alan: Yes, we established the Trust immediately after making the film. Its job was to allow people to channel their expressions of support for the Kogi in a way that the Kogi would know about. We explored various options, and the most practical was the recovery of ancestral land and sites of importance to the Kogi, along with other things attached to it, such as money for health care and administration. But the great thing about land is that it is permanently there, whereas the rest all disappears into the soil as you spend the money.Over the years, lots of people have helped the Kogi acquire further land, including other NGOs and the Columbian government. So the area of territory has greatly expanded. What is more, the new government, which as far as I know is the first socialist government that Colombia has ever had, has just announced a massive expansion of the Tairona National Park, which gives a degree of protection to lands within the area. This includes the traditional territory of the Kogi and the other peoples of the Sierra. But it only gives a degree of protection; it doesn’t actually transfer any ownership to them, although it limits the things that can be done on the land.

‘Don’t Say They Didn’t Tell Us’ – MESSAGE From the Elder Brothers (03/27/2020)

The Arhuaco indigenous peoples of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia, are known for their century-long track record of environmental protection, but their cultural survival and conservation of this sacred mountain’s ecosystems are at risk. Read more here

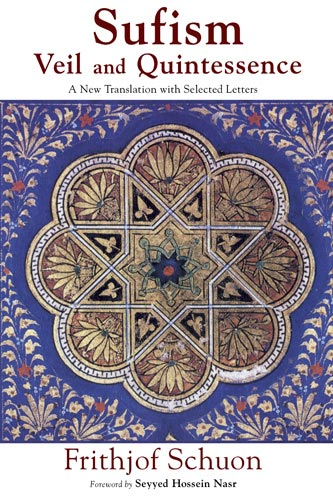

This new edition of perennial philosopher Frithjof Schuon’s Sufism: Veil and Quintessence is a fully revised translation from the French original and contains an extensive Appendix with previously unpublished selections from Schuon’s letters and other private writings. In seven articles Schuon makes the critical distinction between an “absolute” Islam and a “contingent” Islam, thus distinguishing between the message of Islam in itself, and the pious Arab expressions of that message, which by their style of rhetoric have a tendency to veil it.

Table of Contents:

Foreword by Seyyed Hossein Nasr

Editor’s Preface

Preface

Ellipsis and Hyperbolism in Arab Rhetoric

The Exo-Esoteric Symbiosis

Paradoxes of an Esoterism

Human Premises of a Religious Dilemma

Tracing the Notion of Philosophy

The Quintessential Esoterism of Islam

Hypostatic Dimensions of Unity

Appendix

Selections from Letters and Other Previously

Unpublished Writings

Editor’s Notes

Glossary of Foreign Terms and Phrases

Biographical Notes

Index

Free Download here

An excellent summary is this review of the book by the distinguished scholar of Sufism, Seyyed Hossein Nasr:

“In his Sufism: Veil and Quintessence, which is a unique work in the annals of Sufism, [Schuon] has penetrated into the writings of even the greatest masters of Sufism such as al-Ghazzali and Ibn Arabi to reveal within them a quintessential Sufism based on Unity (al-tawhid) and invocation of the Divine Name (al-dhikr) to be distinguished from a more peripheral manifestation of Sufism which displays certain characteristics most difficult for Westerners with the best of intentions to comprehend. In writing with incomparable lucidity and depth about Divine Unity, the esoteric meaning of the Quran, the spirituality of the Prophet, the early saints of Islam, the inner life of prayer, the theophanies to be contemplated in virgin nature and art, the alchemical effect of love, poetry, and music, Schuon has produced a corpus of writings on Sufism which are themselves among the most important and precious works of Sufism.”

—Seyyed Hossein Nasr, George Washington University, and author of many books and articles on Sufism, Islam, and Tradition

Since the inception of psychology as a distinct field of study in the modern West, it has been widely regarded as the only valid form of this discipline, supplanting all other accounts of the mind and human behavior.

The modern West is unique in having produced the only psychology that consciously severed itself from metaphysics and spiritual principles. The momentous intellectual revolutions inaugurated by the Renaissance and the European Enlightenment further entrenched the prejudices of its purely secular and reductionist approach. Yet, across the diverse cultures of the world, we find spiritual traditions that embrace a fully-integrated psychology, unsullied by the limitations of the modern scientific method. It is only by grounding psychology on a foundation of sacred and universal truths—found in all traditional civilizations—that we can begin to restore a true “science of the soul” that addresses the entire gamut of human needs and possibilities. Read here

God became man so that man might become God. — St. Irenaeus

In man the Spirit becomes the ego in order that the ego may become pure Spirit. — Frithjof Schuon

The polarity between what is human and what is spiritual is not only harmonized but actually re-

solved by the plenary principles of the perennial philosophy. It is only through an alignment of humanistic and transpersonal psychologies with the tenets of the perennial philosophy that an integral psychology addressing the entirety of the human person—Spirit, soul and body—may be authentically effective. What has been presented here is only the outline of such an alignment, partial at best, yet it underscores what is indispensable to any operative psychology

that means to address the human being in toto, which is to also say in divinis. We are quite aware that it is a nearly impossible task, or at least a daunting one, to compare the primordial tradition, unanimous in all times and places, with modern psychology.

And although many questions, and important ones at that, remain unanswered, it is throught he guiding light of the perennial philosophy that we may progressively achieve greater clarity on this matter, a viewpoint that reminds us of the immense danger of disowning spirituality, for it is only through the spiritual that man may know what it means to be fully human: “Without the

transcendent and the transpersonal, we get sick, violent, and nihilistic, or else hopeless and apathetic” Rerad more here

The Bhagavad Gita is one of the most influential spiritual texts of ancient India. In Perennial Psychology of the Bhagavad Gita, Swami Rama makes this classic scripture accessible to all students by vividly drawing out the psychological concepts found within. The teachings in this book are based on the understanding that the outside world can be mastered only when one’s inner potentials are systematically explored and realized.With the guidance and commentary of Himalayan Master Swami Rama, you can explore the wisdom of the Bhagavad Gita, which allows one to be vibrant and creative in the external world while maintaining a state of inner tranquility. This commentary on the Bhagavad Gita is a unique opportunity to see the Gita through the perspective of a master yogi, and is an excellent version for practitioners of yoga meditation. Spiritual seekers, psychotherapists, and students of Eastern studies will all find a storehouse of wisdom in this volume. Read here

Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) is one of the most important women of the German Middle Ages and is known today far beyond the borders of her Rhenish homeland. She succeeded in captivating her contemporaries as much as people today who are searching for meaning, orientation, wholeness and salvation. In several songs and texts she uses the expression “Prima Materia”. Hidden in the Latin word “materia” is the word mater = mother. Translated, “Prima Materia” means primordial womb, from which God accomplishes creation. That is why Mary was the center of her veneration, because in Hildegard’s thinking Mary was the embodied “Prima Materia”.

Mary plays a prominent role in the Q’ran: she is the only woman mentioned by name in the Q’ran and after Moses, Abraham and Noah, Mary is the most frequently mentioned person, i.e. she is mentioned more often than Muhammad and Jesus. And the Qur’anic descriptions of her character are consistently full of recognition and admiration. Thus, an entire sura bears her name, Maryam, sura 19. In this sura, mercy itself repeatedly becomes the name of God, thus reminding us that it would be a simplification to associate God only with male attributes. Especially through Mary, a space opens up in these verses to be able to approach God from a female perspective. For the Arabic roots of the word mercy: al rahmam الرَّحمن are the same roots of the word for womb: al rahem الرَحم . Read here Songs in English

Look at me, this little caterpillar man seems to tell us, look at me well; the position seems impossible to hold and yet, you cannot imagine how pleasant it is: I breathe… my skull resting on the soles of my feet, as if earth and sky come together!” Under the impetus of a new energy, all the inhabitants of this tympanum, men and beasts, plants and constellations, also begin their dance around Christ, “New Adam”. This film is a symbolic journey. Thanks to exceptional photos, it invites you to slip into the folds of the stone. It makes vibrate a universal word that outstanding craftsmen, who have remained anonymous, have been addressing to us since the 12th century. It offers everyone, visitors or pilgrims, adults or children, simple landmarks for in-depth reading, a wonder that suspends the march of time. The Great Tympanum of the Basilica of Vézelay “The Dance of the New Adam” DVD

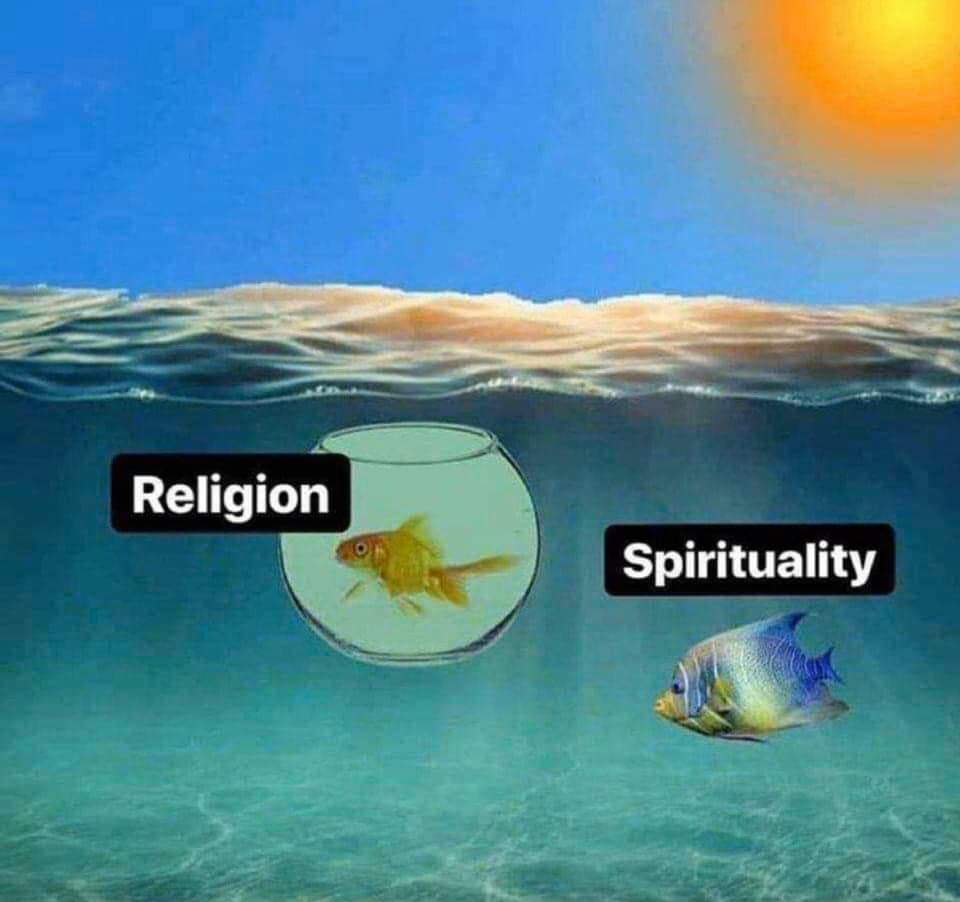

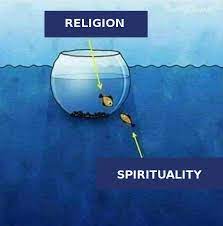

A learned man was once asked to explain the difference between Religion and Spirituality. His response was profound:

▪ Religion is not just one, there are many. ▪ Spirituality is one.

▪ Religion is for those who sleep. ▪ Spirituality is for those who are awake.

▪ Religion is for those who need someone to tell them what to do and want to be guided.

▪ Spirituality is for those who pay attention to their inner voice.

▪ Religion has a set of dogmatic rules. ▪ Spirituality invites us to reason about everything, to question everything.

▪ Religion threatens and frightens. ▪ Spirituality gives inner peace.

▪ Religion speaks of sin and guilt. ▪ Spirituality says, “learn from an error”.

▪ Religion represses everything which is false. ▪ Spirituality transcends everything, it brings you closer to your truth!

▪ Religion speaks of a God; It is not God. ▪ Spirituality is everything and therefore, it is in God.

▪ Religion invents.▪Spirituality finds.

▪ Religion does not tolerate any question. Spirituality questions everything.

▪ Religion is human. It is an organization with rules made by men.▪ Spirituality is Divine, without human rules.

▪ Religion is the cause of divisions. ▪Spirituality unites.

▪ Religion is looking for you to believe.▪ Spirituality you have to look for it to believe.

▪ Religion follows the concepts of a sacred book. ▪ Spirituality seeks the sacred in all books.

▪ Religion feeds on fear. ▪ Spirituality feeds on trust and faith.

▪ Religion lives in thought. ▪ Spirituality lives in Inner Consciousness.

▪ Religion deals with performing rituals. ▪ Spirituality has to do with the Inner Self.

▪ Religion feeds the ego. ▪ Spirituality drives to transcend beyond.

▪ Religion makes us renounce the world to follow a God. ▪ Spirituality makes us live in God, without renouncing our existing lives.

▪ Religion is a cult. ▪ Spirituality is inner meditation.

▪ Religion fills us with dreams of glory in paradise. ▪ Spirituality makes us live the glory and paradise on earth.

▪ Religion lives in the past and in the future. ▪ Spirituality lives in the present.

▪ Religion creates cloisters in our memory. ▪ Spirituality liberates our Consciousness.

▪ Religion makes us believe in eternal life. ▪ Spirituality makes us aware of Eternal Life.

▪ Religion promises life after death. ▪ Spirituality is to find God in our interior during the current life before death. -We are not human beings, who go through a spiritual experience.

-We are spiritual beings, who go through a human experience.

Source UnKnown….

Art of Islam, Language and Meaning: Commemorative Edition, By

Titus Burckhardt, Foreword by Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Introduction

by Jean-Louis Michon, Translated by J. Peter Hobson, Bloomington.

Art of Islam is a masterpiece and is considered to be the most in-depth study on the subject ever written. It was commissioned by the World of Islam Festival (London) and originally published in 1976; in 2009 it was republished in a revised commemorative edition featuring over three hundred fifty color and black-and- white illustrations (two hundred eighty-five of which are new), and including a new introduction.

Titus Burckhardt (1908–1984) was one of the most widely respected authorities on Islamic art as well as having a profound understanding of the Islamic tradition and its mystical dimension, Sufism.

In his foreword, the world-renowned Islamic philosopher, Seyyed Hossein Nasr (b. 1933) has called this classic book “the definitive work on Islamic art as far as the meaning and spiritual significance of this art are concerned” (p. viii). Elsewhere he has written that Burckhardt “had been the first person in the West to expound seriously the inner meaning of Islamic art.”

This work is organized into eight chapters:

(1) Prologue: The Ka‘ba; (2) The Birth of Islamic Art; (3) The Question of Images; (4) The Common Language of Islamic Art; (5) Art and Liturgy; (6) The Art of Sedentaries and Nomadic Art; (7) Synthesis; and (8) The City.

This volume brings the wide spectrum of art within the Islamic tradition to broader audiences. It also provides the spiritual keys to discern these forms and to connect them to the metaphysical principles of the Islamic revelation, which is to see that its art forms are the earthly crystallization of Islam itself. To ask the question “What is Islam?” it would suffice to point to one of its remarkable art forms such as the Mosque of Córdoba, Ibn Tulun in Cairo, one of the madrasahs in Samarqand or the Taj Mahal. Hence what is considered to be the most outward manifestation of religion or civilization, such as art, correspondingly reflects its most inward dimension of that civilization.

In Islam, the outward is known as az- zahir and the inward as al-batin, a perspective that views God as both transcendent and immanent, both of which are joined in the Divine Unity (tawhid). The birth of all sacred art, in fact, is associated with the exteriorization of that which is most

inward in every sapiential tradition; therefore, there is an important connection between art and the mystical dimensions of all religions.

The Ka‘ba, as the liturgical center of the Muslim world, is inextricably linked to the origin of the Abrahamic monotheisms—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—and demonstrates Islam’s connection to all the monotheist religions. The notion of center and origin are presiding ideas, as they are “two aspects of one and the same spiritual reality, or again, one could say, the two fundamental options of every spirituality” (p. 1). The Koran explains that “Abraham was neither Jew nor Christian, but detached (hanif) and submitting (muslim)…” (3:67). Abraham was the apostle of pure and universal monotheism, which the Islamic tradition purposes to renew. The Ka‘ba, although not a work of art as such, can be regarded as “proto-art” whose metaphysical dimension is linked to myth and revelation, therefore containing the embryo of the whole of Islamic art.

According to Burckhardt “The art of Islam … is abstract, and its forms are not derived directly from the Koran or from the sayings of the Prophet; they are seemingly without scriptural foundation, while undeniably possessing a profoundly Islamic character” (p. 7). He adds that “Art never creates ex nihilo. Its originality lies in the synthesis of pre-existing elements” (p. 18).

The prohibition of images in Islam is specifically associated with images of the Divine. As Islam is the renewal of Abrahamic monotheism, the Prophet Muhammad, as Abraham before him, opposes idolatrous polytheism. To produce images of the Divine is to perpetuate the error that associates the relative with the Absolute or the created with the Uncreated, reducing one level to another. The term aniconism is used to depict the art of Islam, which differs from iconoclasm. Burckhardt elaborates:

As for Islamic aniconism, two aspects in all are involved. On the one hand, it safeguards the primordial dignity of man, whose form, made “in the image of God”, shall be neither imitated nor usurped by a work of art that is necessarily limited and one-sided; on the other hand, nothing capable of becoming an “idol”, if only in a relative and quite provisional manner, must interpose between man and theinvisible presence of God. What utterly outweighs everything else is the testimony that there is “no divinity save God”; this melts away every objectivization of the Divine before it is even able to come forth. (p. 32)

The immutable essences (al-a’yan ath-thabitah) of things, their archetypes, are not apprehended, as they are beyond form; however, they are reflected in the contemplative imagination of the believer. Everything that exists in the cosmic order, exists in this hierarchy, which manifests qualitatively and not quantitatively.

Burckhardt states:

The most profound link between Islamic art and the Koran … lies not in the form of the Koran but in its haqiqah, its formless essence, and more particularly in the notion of tawhid, unity or union, with its contemplative implications; Islamic art … is essentially the projection into the visual order of certain aspects or dimensions of Divine Unity. (p. 51)

Calligraphy is a widely used art form among Muslims. In weaving the horizontal and vertical movement of the script, change and becoming are juxtaposed with what is immutable. Burckhardt adds, “The vertical is therefore seen to unite in the sense that it affirms the one and only Essence, and the horizontal divides in the sense that it spreads out into multiplicity” (p. 54).

As human diversity is inexhaustible, so is the cosmic order, all of which is contained in the Divine Unity. It is reflected through harmony, which is expressed as “unity in multiplicity” (al-wahdah fi’l-kathrah) and “multiplicity in unity” (al- kathrah fi’l-wahdah). This interpenetration is the expression of one abiding in the other, yet all things ultimately return to the Divine Unity. Again, “Islam is the religion of return to the beginning, and … this return shows itself as a restoration of

all things to unity” (p. 66).

The central theme of the Islamic tradition is Divine Unity, which exists a priori everywhere and always. The decisive task for the human being is to realize the Divine Unity in him or herself and the cosmic order.

Worship is inseparable from beauty, as the hadith instructs: “God has inscribed beauty upon all things.” Hence, “Sacred art … fulfills two mutually complementary functions: it radiates the beauty of the rite and, at the same time, protects it.” (p. 88)

From this perspective, a rite itself is sacred art. A pulpit, known in Arabic as a minbar, symbolizes the ladder of the worlds—these are the corporeal, the psychic, and the spiritual.

Note: SALAH AL-DIN MINBAR OF AL-AQSA MOSQUE

Salah Al-Din Minbar (pulpit) has a distinguished value in Islamic art, which is originated from its historical value of being constructed 800 years ago epresenting a symbol of dignified historical era; and to its political

value as this Minbar had formed an emotional spur during the Crusades; and above all it is considered as one of the most beautiful and finest pieces of Islamic decoration art. Read Here

There is a liturgical and artistic role of clothing in Islam. Burckhardt clarifies, “To veil the body is not to deny it, but to withdraw it like gold, into the domain of things concealed from the eyes of the crowd” (p. 105).

The significance of the carpet within Islamic spirituality is illuminated here, It is the image of a state of existence or simply of existence as such; all forms or happenings are woven into it and appear unified in one and the same continuity. Meanwhile, what really unifies the carpet, namely the warp, appears only on the borders. The threads of the warp are like the Divine Qualities underlying all existence; to pull them out from the carpet would mean the dissolution of all its forms. (p. 119)

Burckhardt maintains that art should be “typified by beauty” and dismisses contemporary discussions of functions by stating that “certain functions owe their existence to man’s decadence” (p. 156). He adds, “The only beautiful work of art is the one which, in some way, reflects integral human nature whatever its incidental function” (p. 156). There is an important awareness of the ephemerality of all things in the cosmic order; for this reason, art always includes something provisional pertaining to it—“We shall surely make all that is upon it [the earth] barren dust” (Koran 18:8).

Burckhardt’s work has stood the test of time and has demonstrated its enduring value to those wanting to understand the art of Islam. Because modern art has no parallels with Islamic art, or any sacred art, for that matter, it challenges the Western mindset and its Eurocentrism—its ability to appreciate art as understood in a theocentric civilization, where nothing stands outside the sacred. Art in this context contains something beyond its artistic form, something timeless and universal, as there is no “art for art’s sake” in Islam or any other sacred art. The important connection between sacred art and contemplation has been forgotten and lost in the modern world. The Prophet defines ihsan as “serving [or worshiping] God as if you see Him, because if you do not see Him, He nonetheless sees you.” It is in tracing beauty, whether in a form of art or in the cosmic order, back to the origin that we can realize that the metaphysical dimensions of aesthetics are a doorway to the Divine. As the Prophet has expressed it, “God is beautiful and He loves beauty” (p. 224).