- The Acedia virus is spreading rapidly among people

Many people have a feeling of stress and overload, of lethargy and a lack of motivation, of fear and uncertainty about the future. The word Acedia is used for that complex feeling. Acedia is not new. The Greek poet Homer already used the word to mean ‘neglect, lack of care’. Later on, acedia also came to mean ‘listlessness’, ‘sluggishness’ and ‘inertia’.

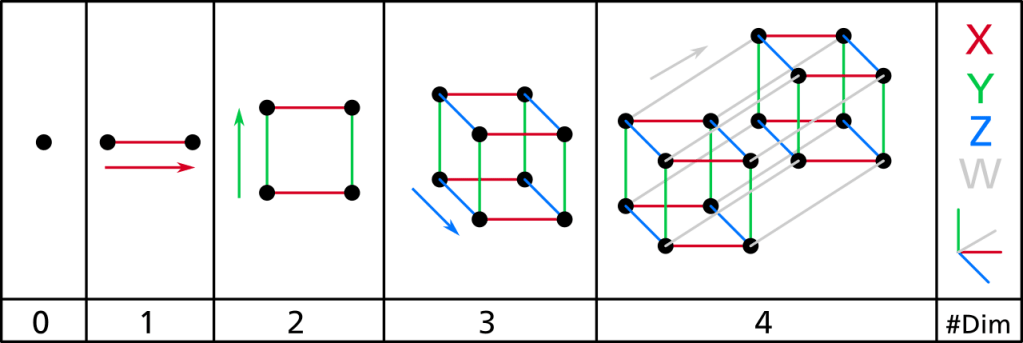

If you look at our life, you notice that you mainly end up in the 1D and 2D living level due to this Acedia virus. Your life becomes straightforward and superficial. Your self-made boundaries are coming at you more and more. Your inner freedom is getting smaller and smaller. This is because we are fighting against our own nature. Because we want to save people at all costs, we end up in an unnatural downward spiral. This is not the natural intent. The Corona virus is a message to people. It will not disappear and dissolve until we follow our own nature. By clinging to the unnatural thinking, doing and making system of humanity, we will have to deal with much more natural resistance. If we really listen to this resistance, we will find out that nature has what is best for us.

So many people are now stuck in their 1D and 2D lives, causing an extreme unnatural deformity and skewed growth. Only humans are capable of this on this planet, because we have the consciousness to deviate from the natural path. We have abused this gift enormously. Humanity has started to think, act and make in deviations. We do not use the deviations to create a new natural path, but to fight the natural path. Because we do not make use of a natural creation process in all our thinking, doing and making, we are becoming increasingly distant from ourselves and nature. We see and experience all the nasty consequences of this, but we also try to combat it by fighting even harder against nature and ourselves. All faith in natural existence has been broken by ourselves. You can fix this again by starting the natural creation process. It all has to do with our imagination. Our imagination determines the path we follow. It is necessary to direct this imagination with our consciousness. This does not require a 3D living level, but a natural 4D living level. At a 4D living level you live from the center of consciousness. Through everything who you are comes together. By disconnecting your consciousness from your imagination, a tension arises between the two. The first step towards natural shaping of yourself and your environment is to feel this field of tension. Only when you feel this can you ensure a natural balance.

The Acedia virus is the most contagious virus. The leaders of the unnatural deformed system make decisions that create even more deformities and chaos. They don’t know any better. The Acedia virus is a persistent virus, because it is invisible and unnoticeable to many. So it does not exist in the eyes of the masses who are in charge. It is only a matter of time before humanity realizes that things have to change completely. This is a natural need such as needing to breathe, eat and drink. If humanity is to win, it must defeat itself. Man has become his own worst enemy because of the Acedia virus. If we do not realize this, then the emptiness, nature will continue to force itself more and more violently until we give up this unnatural struggle and start shaping everything again and naturally.

- The Acedia virus as Afternoon Devil

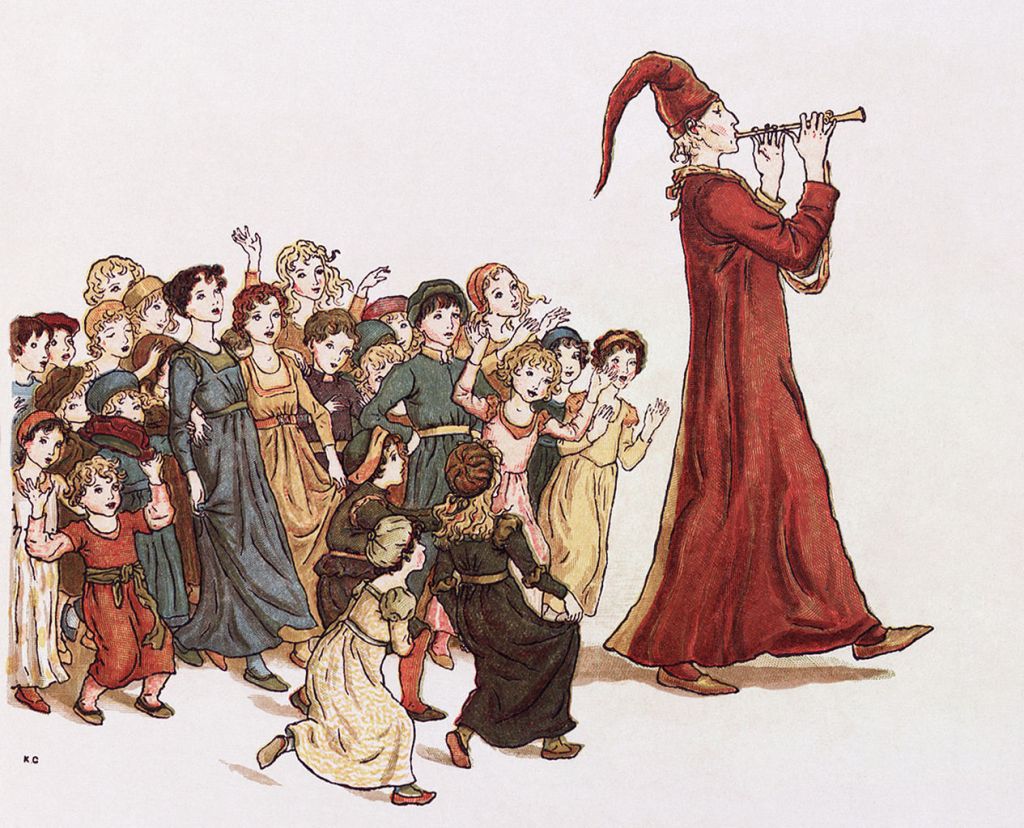

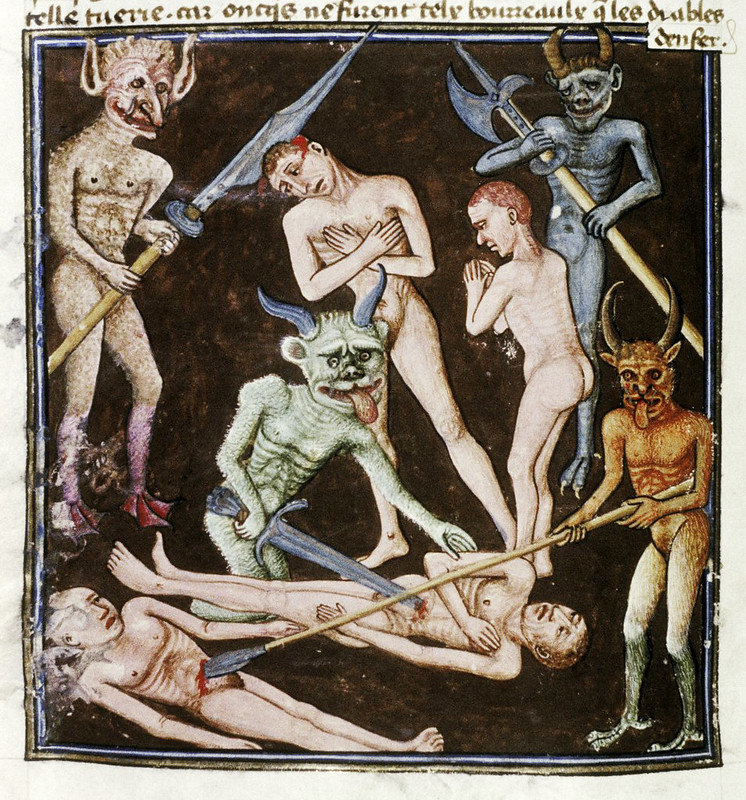

Not only St Antony, many desert fathers were busy fighting off demon attacks: bearded devils, venomous snakes with a human head, seductive women who turned into crocodiles or masturbating apostles. Presumably all those images were projections, and/or due to chemical reactions in the brain, caused by sleep deprivation and extreme fasting periods.

The most dangerous demon was the so-called midday devil, who tried to seduce the hermits into spiritual dullness and eventually abandon their way of life. Especially when they lived alone, the ascetics often became miserably stressed and fell into dejection, restlessness, and a psychotic aversion to their filthy dens and lonely caves. Their state of mind, which arose mainly around noon, in the heat of the day, was accurately described in the writing Praktikos , or The Monk, composed in the fourth century by the desert father Evagrius . For the malaise he uses the Greek word akèdeia , which means something like ‘indifference’ or ‘listlessness’ (in Latin: acedia ; in English the word accidie derived from it still exists , in Italian accidia ).

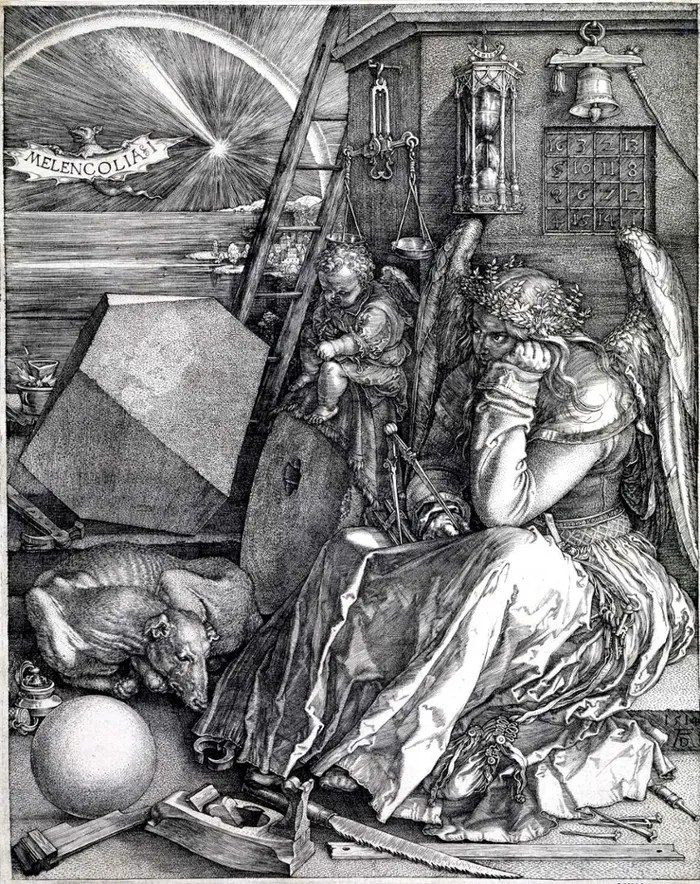

- Melancholy

In later times the acedia breaks away from the midday devil and manifests itself under other names: melancholy, taedium vitae (aversion to life), nostalgia, apathy, Weltschmerz, ennui , frustration,” nausée” ( Sartre’s Nausea), boredom and finally depression, that modern container concept. In the Renaissance, the body replaces God. Melancholy means black bile, which is one of the four bodily fluids necessary for good, balanced health. Those who have too much black bile become sad and depressed. In the modern phase, the acedia becomes medicalized, giving rise to “a strange amalgam of depression and doubt of the benevolence of reality”). The same goes for drug use.

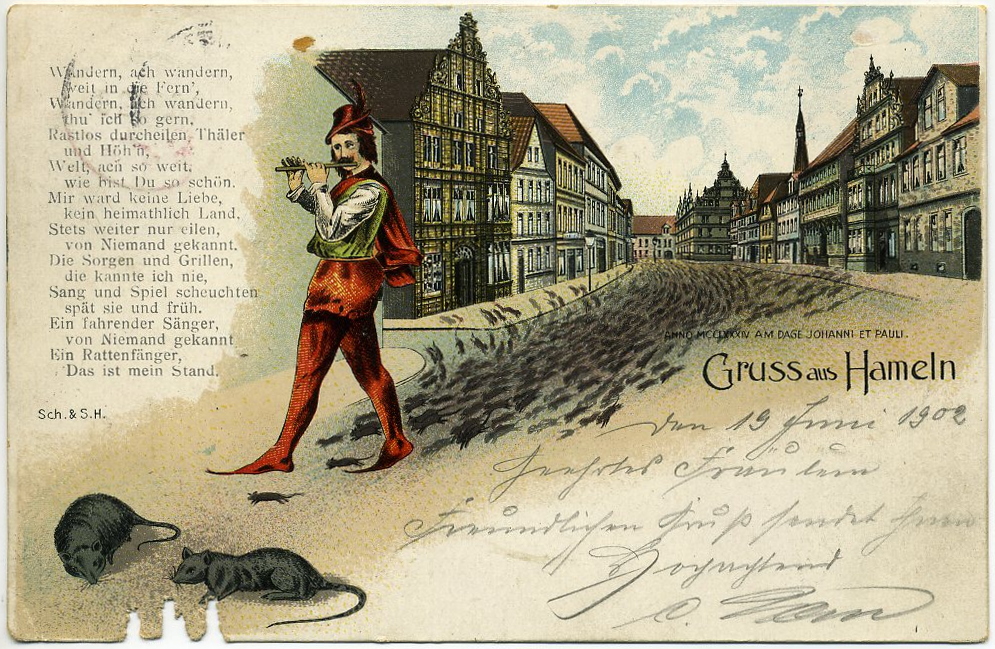

Boredom is the fundamental mood of contemporary society. The psychiatrists and psychotherapists are busy with the resulting depressions. The entire modern entertainment industry lives by man’s need for stimuli that (temporarily) relieve him from everyday boredom. A very special form of the phenomenon is the dromomania or morbid wanderlust. Dromomania literally means: mania for locomotion. It mainly affects wealthy elderly people who can afford to take a quick look at all the wonders of the planet just before saying goodbye. One cruise is not yet over or the suitcases for the other are already ready. Finally, the boredom of the nursing home also awaits them.

- The salvation of yourself

The instability has to do with the fact that you are always looking for distraction. Even if that is in the form of a different education or hobby, you suffer from Acedia . Being too busy with your health is also less positive than we think. It can also mean that you are only disciplining your body and totally neglecting your mind. Poor compliance with rules means as much as not fulfilling your obligations. Not only cutting corners, but working too hard can be a sign of a general feeling of discouragement or desolation. Acedia eventually even makes you doubt your state of life or your calling. You feel like you’re never going to achieve what you need to achieve and that, in short, it’s all pointless. You have no inner strength left and so you flee into laziness, working too hard, or doing nothing. It takes some getting used to this. We’ve all learned to pathologize our gloomy feelings. We use phrases like “I’m depressed” or “I’m so autistic about that”. Would a broader definition of apathy give a more truthful picture of humanity? Not being able to push yourself to anything can be a signal that there’s more to it than you think. Apathy is actually the opposite of persistence.

Persistence when you’re despondent may sound tough, but it’s pretty simple. By staying true to your life as it is, the duties you now have to do, you can overcome your sense of malaise. By sticking to your daily tasks like a stairway to heaven and by climbing in faith, you can overcome even the most severe despondency and grow as a person.

So the next time you’re despondently putting things off, and you realize that your time on social media isn’t bringing you any live contacts, maybe read this quote from the desert monk Arsenius (4th century). “Go to your room, eat something, sleep and do no work for a while, but don’t leave your room under any circumstances!”

– The Noonday Devil: Acedia, The Unnamed Evil of Our Times a book by Jean-Charles Nault, OSB

The noonday devil is the demon of acedia, the vice also known as sloth. The word “sloth”, however, can be misleading, for acedia is not laziness; in fact it can manifest as busyness or activism. Rather, acedia is a gloomy combination of weariness, sadness, and a lack of purposefulness. It robs a person of his capacity for joy and leaves him feeling empty, or void of meaning

Abbot Nault says that acedia is the most oppressive of demons. Although its name harkens back to antiquity and the Middle Ages, and seems to have been largely forgotten, acedia is experienced by countless modern people who describe their condition as depression, melancholy, burn-out, or even mid-life crisis.

He begins his study of acedia by tracing the wisdom of the Church on the subject from the Desert Fathers to Saint Thomas Aquinas. He shows how acedia afflicts persons in all states of life— priests, religious, and married or single laymen. He details not only the symptoms and effects of acedia, but also remedies for it. Here a summary:

3 Definitions of Acedia

#1: “Spiritual lack of care.” – Evagrius of Pontus

- Evagrius of Pontus (345-399), who was the first to present a coherent doctrine on acedia, adapted the original Greek understanding of acedia as a physical “lack of care” (specifically with regard to not arranging a funeral for your deceased family members) into a spiritual “lack of care” (with regard to your own spiritual life). Evagrius personified acedia, calling it “the noonday devil” (cf. Ps 90:6) and the “most oppressive of all the demons” because acedia is able to conceal itself from the one who experiences it.

- “Acedia is the temptation to withdraw from the narrowness of the present so as to take refuge in what is imaginary; it is the temptation to quit the battle so as to become a simple spectator of the controversy that is unfolding in the world”

#2: “Sadness about spiritual good.” – St. Thomas Aquinas

- Aquinas says that acedia is a negative reaction (sadness) about participating in God’s life (spiritual good) because we are unwilling to renounce a particular carnal, temporal, limited, apparent good that stands in the way of our true good.

With acedia, we are discouraged, spiritually depressed, and fall into despair. We choose to live in mediocrity, usually manifest through little everyday infidelities. “We are unable to believe in the greatness of the vocation to which God is calling us: to become sharers in the divine nature”

#3: “Disgust with activity.” – St. Thomas Aquinas

- Since “our acts are like steps that either bring us closer to the vision of God or else distance us from it, depending on whether they are good or bad” 4), an interior, spiritual disgust (weariness, sloth, boredom) with activity is, therefore, an obstacle to beatitude.

- This definition of acedia is rooted in John Cassian’s (360-433) presentation of acedia as a lack of impetus to work.

- We feel a constant need to change, to move, an inability to accomplish any task, rooted in a self-sufficiency that presents itself as a false humility in not striving for greatness.

- “I have discovered that all human misfortune comes from one thing, which is not knowing how to remain quietly in one room” (Blaise Pascal).

The Importance of Acedia

Acedia is both the most forgotten topic of modern morality nd perhaps the root cause of the greatest crisis in the Church today. Acedia is not only “the monastic sin par excellence” but also “the major obstacle to enthusiastic Christian witness”

Remedies for Acedia

#1: Joyful perseverance

- “The strategy to be deployed against the devil of acedia can be summarized in the phrase: joyful perseverance” (

- We must resist, stand fast, remain faithful to our routine and rule of life, and persevere in God’s sight.

- “Restore to me the joy of your salvation, and uphold me with a willing spirit” (Ps 51:12). This is the prayer that must dwell in our hearts on days of acedia. It sums up perfectly our spiritual attitude when confronted by temptation. We are radically saved, restored to life with Christ: our sadness has definitively been changed into joy (Jn 16:20). This gaudium resulting from the Resurrection of Christ is something that we must show; we must witness to it. We are called to a marvellous work: to help others – to the merger extent that we can, in other words, by our excellent actions – to walk toward our perfect fulfillment in Christ. Now this requires magnanimity, greatness of soul” ).

#2: Be faithful in the little things

- We must live the present moment in all its spiritual intensity, knowing that it is an opportunity to encounter the Lord.

- We must be faithful in the very little things (Lk 16:10; 19:17; Mt 25:21), especially in ora et labora, that is, prayer and work.

#3: Use the Word of God

- Use a verse from Scripture to confound the devil. We must “raise our eyes toward heaven, toward Him who waits to see us fight” (136): “O God, come to my assistance; O Lord, make haste to help me” (Ps 69).

- St. Benedict (480-547) situated acedia within the context of lectio divina, prescribing praying with the Word of God as the true antidote against acedia: “When evil thoughts come into one’s heart, to dash them against Christ immediately” (St. Benedict).

#4: Meditate on death

- This gives meaning to passing time and helps you fight against self-love: “keep death daily before one’s eyes” (St. Benedict).

- “Make me know the shortness of my life, that I may gain wisdom of heart” (Ps 90).

- “Someone asked an old man: “What do you do to avoid falling into acedia?” He replied: “Every day I wait for death.”

- ————————————————————-

- Note: Mutiny of the Soul

- Depression, anxiety, and fatigue are an essential part of a process of metamorphosis that is unfolding on the planet today, and highly significant for the light they shed on the transition from an old world to a new.

- When a growing fatigue or depression becomes serious, and we get a diagnosis of Epstein-Barr or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome or hypothyroid or low serotonin, we typically feel relief and alarm. Alarm: something is wrong with me. Relief: at least I know I’m not imagining things; now that I have a diagnosis, I can be cured, and life can go back to normal. But of course, a cure for these conditions is elusive.

- The notion of a cure starts with the question, “What has gone wrong?” But there is another, radically different way of seeing fatigue and depression that starts by asking, “What is the body, in its perfect wisdom, responding to?” When would it be the wisest choice for someone to be unable to summon the energy to fully participate in life?

- The answer is staring us in the face. When our soul-body is saying No to life, through fatigue or depression, the first thing to ask is, “Is life as I am living it the right life for me right now?” When the soul-body is saying No to participation in the world, the first thing to ask is, “Does the world as it is presented me merit my full participation?” Read More Here

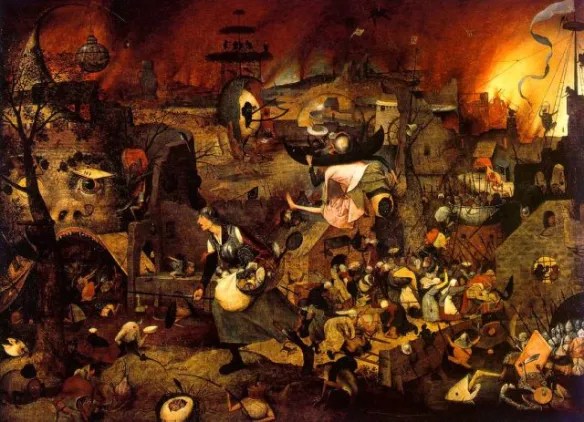

The “Dulle Griet” as “whore of Babylon” , in the land of Ignorance by Brueghel

Dulle griet is the representation of the Whore of Babylon living in a land of Ignorance.

The Whore of Babylon in the The Apocalypse Tapestry of Angers

The Whore of Babylon or Babylon the Great is a symbolic female figure and also place of evil mentioned in the Book of Revelation in the Bible. Her full title is stated in Revelation 17 (verse 5) as Mystery, Babylon the Great, the Mother of Prostitutes and Abominations of the Earth.

The word “Whore” can also be translated metaphorically as “Idolatress“.[1] The Whore’s apocalyptic downfall is prophesied to take place in the hands of the image of the beast with seven heads and ten horns. There is much speculation within Christian eschatology on what the Whore and beast symbolize as well as the possible implications for contemporary interpretation.

Look also: Bruegel: the Apocalypse Within

Dulle Griet is the model of modern man’s Rebellion against his soul and Anger against it. How can Dulle Griet find a way to calm her anger?

She can looks in the mirror and see herself,making more “selfies”, so seeing more anger as the portait of vanity of Hans Memling shows us:. The lady see only more vanity .

The message of Memling is in his Triptych of Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation focuses on the idea of “Memento mori,” a Latin phrase that translates to “Remember your mortality.” Memling’s triptych shockingly contrasts the beauty, luxury and vanity of the mortal earth with images of death and hell. In the time of Breughel and in our times the message is that Vanity is not the solution. see: Nothing Good without Pain: Hans Memling”s earthly Vanity and Divine Salation

All Is Vanity by Charles Allan Gilbert (September 3, 1873 – April 20, 1929)

The phrase “All is vanity” comes from Ecclesiastes 1:2 (Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities; all is vanity.

Don’t change the world in hopes of changing yourself,

change yourself so the world changes because of you.

——————————————————

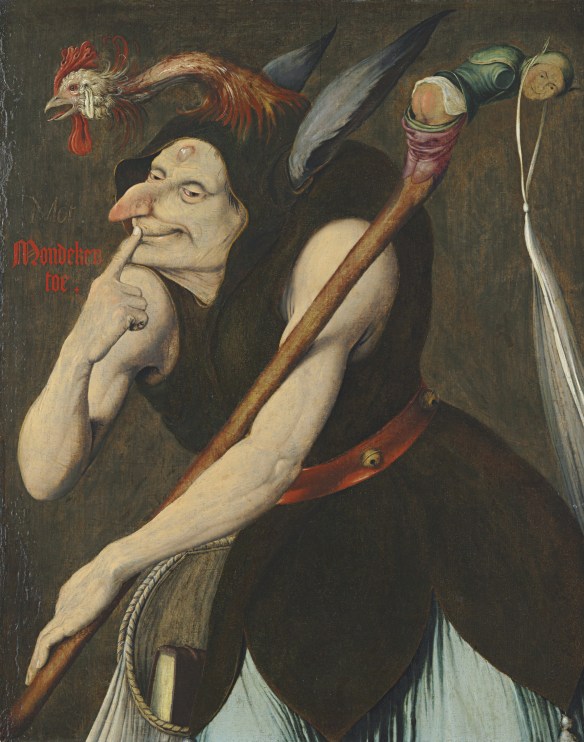

- Praise of folly

“The supreme madness is to see life as it is and not as it should be, things are only what we want to believe they are ...”

Jacques Brel

- Allegory of the cave

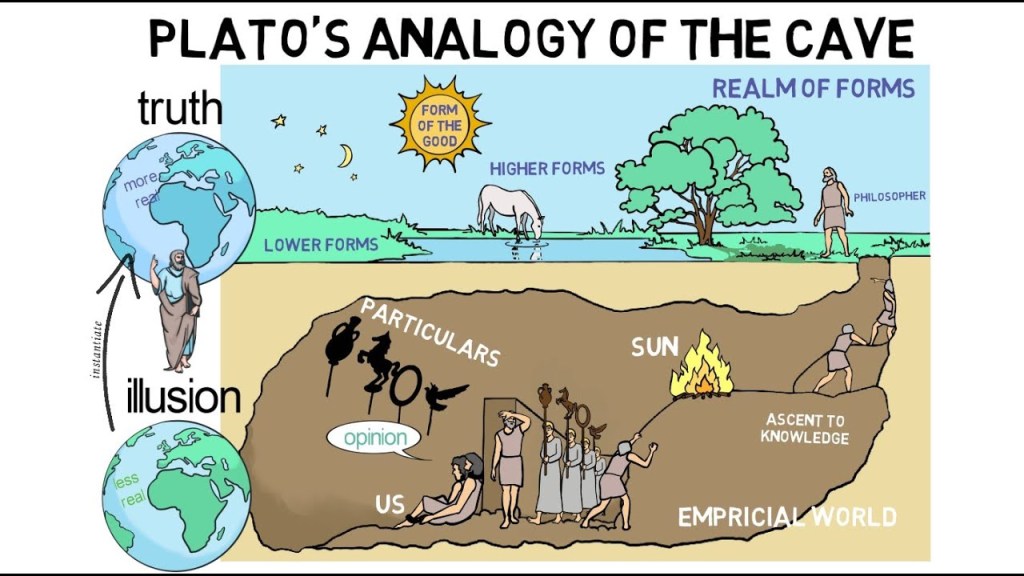

The Allegory of the Cave, or Plato’s Cave, is an allegory presented by the Greek philosopher Plato in his work Republic (514a–520a) to compare “the effect of education (παιδεία) and the lack of it on our nature“. It is written as a dialogue between Plato’s brother Glaucon and his mentor Socrates, narrated by the latter. The allegory is presented after the analogy of the sun (508b–509c) and the analogy of the divided line (509d–511e).

In the allegory “The Cave,” Plato describes a group of people who have lived chained to the wall of a cave all their lives, facing a blank wall. The people watch shadows projected on the wall from objects passing in front of a fire behind them and give names to these shadows. The shadows are the prisoners’ reality, but are not accurate representations of the real world. The shadows represent the fragment of reality that we can normally perceive through our senses, while the objects under the sun represent the true forms of objects that we can only perceive through reason. Three higher levels exist: the natural sciences; mathematics, geometry, and deductive logic; and the theory of forms.

Socrates explains how the philosopher is like a prisoner who is freed from the cave and comes to understand that the shadows on the wall are actually not the direct source of the images seen. A philosopher aims to understand and perceive the higher levels of reality. However, the other inmates of the cave do not even desire to leave their prison, for they know no better life.[1]

Socrates remarks that this allegory can be paired with previous writings, namely the analogy of the sun and the analogy of the divided line.

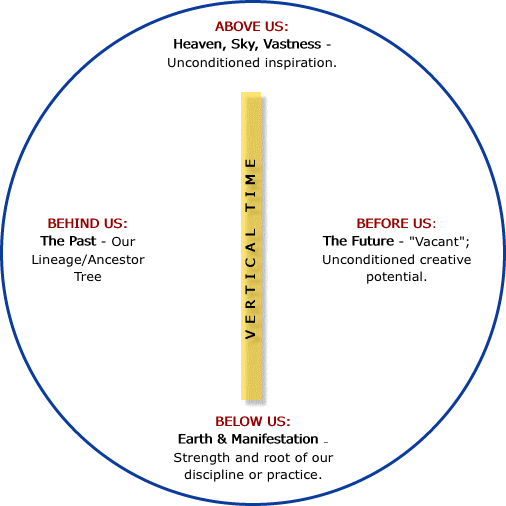

– The principle of verticality

The principle of verticality, which is a fundamental principle of traditional wisdom, is based on the affirmation of transcendence as an aspect of a comprehensive and integrated reality that is Absolute.

According to this understanding, reality has both a transcendent Origin and an immanent Center, which are one, rather than being reduced to the merely horizontal dimension of its existential or quantitative elements.

Verticality implies both Heaven and Earth, a worldview in which meaning and purpose are defined principally by both height and depth,and secondarily by breadth – that is, principally by man’s relationship to God, who is simultaneously ‘above’ and ‘within’ creation, and who there-fore governs all creaturely relationships – rather than by breadth alone –that is, solely in terms of the relationship between the subject and the world.

It also implies that the horizontal is subordinate to the vertical,that is to say, the relationship between man and the world is premised on the primary relationship between God and man: to restate this in Christian terms, the love of one’s neighbor is premised on one’s love for God. According to the traditional worldview, existence is transcended by a supreme reality, which, whether expressed in theistic or non-theisticterms, is Absolute, and which, without derogating from its unity, is si-multaneously (at the level of the primary hypostasis) expressed by the horizontal ternary, Truth or the Solely Subsistent Reality, Goodness or the Perfection and Font of all Qualities, and Beauty or Abiding Serenity and the Source of its Radiant Effulgence: in Platonic terms, the True, the Good and the Beautiful.

All creation is prefigured in this supreme reality,which projects existence out of its own Substance into a world of form (hence etymologically, ex-stare, to stand out of, or to subsist from, as the formal world of existence stands out of, and subsists from, the Divine Substance) through a vertical ternary comprising, first, the Essential or Principial Absolute (which is Beyond-Being), second, the Relative-Absolute Source of Archetypes (which is the primary hypostasis of Being), and third, the realm of Manifestation (which is Existence).

The world itself,and its creatures, including man, as such, are therefore of derivative significance and are accidental in relation to the supreme reality, which alone is substantial. The world is transient, ephemeral and illusory.

The Divine Substance alone is permanent and real. This view of the transcendent, supreme and substantial reality of the Absolute (which, according to the principle of verticality, is described in terms of its elevation orperfection in relation to creation) finds its expression in all religious traditions.

The Sufi Master Sheikh Nazim al Haqqani al Rabbani says: We change Reality by changing our Perception of it.There is much to be learn about Eternity by living in Time and There is much to be learn about Time by living in Eternity

So it is time to look at eternity:

What is time and pre-eternity?

We change Reality By changing our perception of it

There is much to be learn about Eternity by living in Time

There is much to be learn about time by living in Eternerty

What is our Destiny:

Tthe sacred Tradition as Sufism an Islam explains the most important cause for misunderstanding the issue of qadar (destiny) is confusion about the concepts of “time” and “pre-eternity” and misinterpreting them.

People live in time and place and so they evaluate every event according to time and they make a mistake by assuming “pre-eternity” as the beginning of “time”. Misunderstanding qadar is the result of this wrong comparison.

Time is an abstract concept. It starts with the creation of the universe and many events happen in it. Time is divided into three parts: Past, present and future. This division is for creatures. Namely, the concepts such as century, year, month, day, yesterday, today, tomorrow are in question for creatures.

Pre-eternity does not mean before the beginning of the time. In pre-eternity, there is no past, present and future. Pre-eternity is a station where all times are seen and known at the same moment. Now, we will try to understand God’s attribute of pre-eternity through some examples from Sufism and Islam:

Suppose that this picture is our timeline. The middle is the present, that is, now; the left side is the past and the right side is the future. Now, we are holding a mirror on the time scheme. The mirror is close to the floor; so, only the present time is reflected on the mirror. The past and the future are not included. Now, we will lift the mirror a bit and in this position, the present time and a part of the past and the future are reflected on the mirror. When we lift the mirror a little more, the remaining part of the past and the future that are not seen in the previous position are also reflected on the mirror. That is, as we lift the mirror, the time period which appears on the mirror expands. Now, we will lift the mirror to the highest point.

At this point, the mirror encompasses the present, past and future as a whole. This point is called the point of pre-eternity, which sees all of the three times as a whole at the same moment. When we say, “Allah is pre-eternal”, we mean that Allah sees and knows all times and places at the same moment and that He is timeless.

The Metaphysics of Trauma

Trauma, which has become a hallmark of everyday life in the modern world, forms part of the broader mental health crisis that afflicts society today. It also, arguably, reflects a lost sense of the sacred. Throughout humanity’s diverse cultures, suffering is understood to be intrinsic to the larger fabric of life in this world; trauma, therefore, is a direct consequence of not being able to properly integrate suffering into one’s life. However, this is not to simply equate suffering with trauma, or trauma with illness. The prevalence of acute traumatic suffering has always been a major cause of disbelief in religion. Yet the increased weakening of faith in the modern world has provoked a particularly severe spiritual crisis, which could be dubbed the “trauma of secularism.” Through recourse to traditional metaphysics, we can begin to understand the transpersonal dimension of this phenomenon and thus accurately assess, diagnose and provide adequate treatment. It will be argued that healing and wholeness cannot take place outside the purview of a “sacred science,” the spiritual dimension of which transcends the limitations of mainstream psychology and its profusion of profane therapies. Read here

- The Symbolism of the Cross

The Symbolism of the Cross is a major doctrinal study of the central symbol of Christianity from the standpoint of the universal metaphysical tradition, the ‘perennial philosophy’ as it is called in the West. As Guénon points out, the cross is one of the most universal of all symbols and is far from belonging to Christianity alone. Indeed, Christians have sometimes tended to lose sight of its symbolical significance and to regard it as no more than the sign of a historical event. By restoring to the cross its full spiritual value as a symbol, but without in any way detracting from its historical importance for Christianity, Guénon has performed a task of inestimable importance which perhaps only he, with his unrivalled knowledge of the symbolic languages of both East and West, was qualified to perform. Although The Symbolism of the Cross is one of Guénon’s core texts on traditional metaphysics, written in precise, nearly ‘geometrical’ language, vivid symbols are necessarily pressed into service as reference points-how else could the mind ascend the ladder of analogy to pure intellection? Guénon applies these doctrines more concretely elsewhere in critiquing modernity in such works as The Crisis of the Modern World and The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times, and invokes them also to help explain the nature of initiation and of initiatic organizations in such works as Perspectives on Initiation and Initiation and Spiritual Realization. Read here

The Multiple States of the Being

The Multiple States of the Being is the companion to, and the completion of, The Symbolism of the Cross, which, together with Man and His Becoming according to the Vedanta, constitute René Guénon’s great trilogy of pure metaphysics. In this work, Guénon offers a masterful explication of the metaphysical order and its multiple manifestations-of the divine hierarchies and what has been called the Great Chain of Being-and in so doing demonstrates how jñana, intellective or intrinsic knowledge of what is, and of That which is Beyond what is, is a Way of Liberation. Guénon the metaphysical social critic, master of arcane symbolism, comparative religionist, researcher of ancient mysteries and secret histories, summoner to spiritual renewal, herald of the end days, disappears here. Reality remains. look here

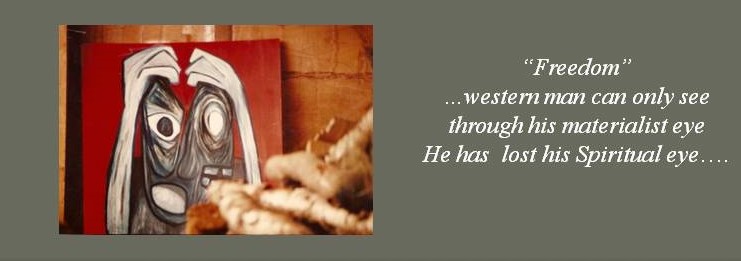

“The secularity of the society in which we live must share considerable blame in the erosion of spiritual powers of all traditions, since our society has become a parody of social interaction lacking even an aspect of civility. Believing in nothing, we have preempted the role of the higher spiritual forces by acknowledging no greater good than what we can feel and touch.” Vine Deloria Jr

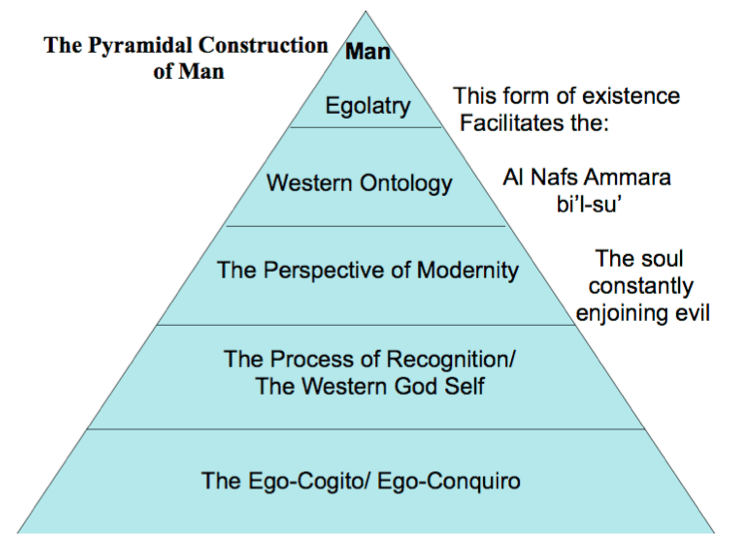

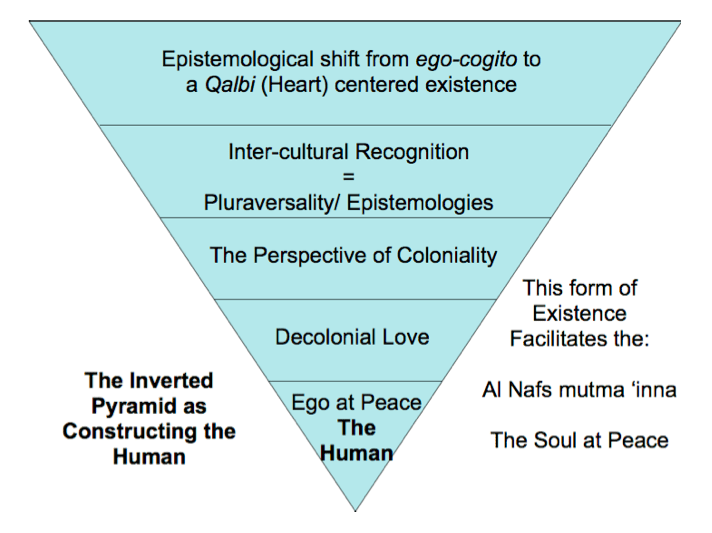

The perspective of modernity where Western Man as the egolatrous being is placed at the top of existence for all others to look towards for recognition.

The pyramidal construction of Man from an Islamic perspective shifts our understanding of the seriousness of placing the egolatrous Man above God in constructing reality, while simultaneously allowing us to imagine what would be necessary in creating a transmodern critique in constructing the Human.

Read here:

THE ISLAMIC CONCEPT OF HUMAN PERFECTION

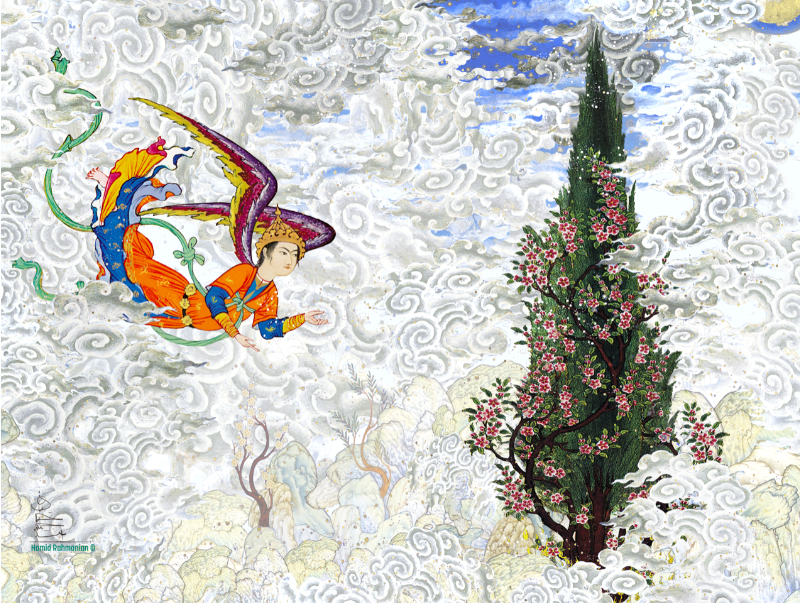

Rumi: A Disclosure of Wisdom for our Time