The Natural Law of Compassionate Justice, An Islamic Perspective

Maandelijks archief: oktober 2020

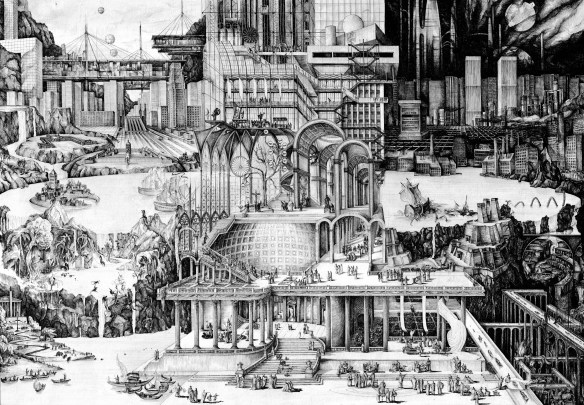

A History of the Utopian Tradition: A guide for our times

- A History of the Utopian Tradition

By Carlijn kingma CARTOGRAPHY OF SOCIETY

Chinese Ink and dip pen on paper Size original drawing: 1189mm x 841mm

April 2016 -For more information about the prints, please send an email to: carlijnkingma@gmail.com.

Below you can read the introduction of the story:

The urge to transcend and push life ‘as it is’ in order to move towards life ‘as it should be’, is a defining feature of humanity. Utopia is a way of articulating of this urge – a project or vision which provides us with a clear view on an alternative present or future world, through which, although sometimes just for one little moment, we can believe in something extraordinary. Utopia has long been the name for the unreal and the impossible. We have set utopia over against the world as the world of dreams, fantasies and ideas. Thus, sometimes, we seem to forget, that, like Lewis Mumford used to say, the choice we have is not between reasonable proposals and an unreasonable utopianism. Utopian thinking does not under- mine or discount real reforms. Indeed, it is almost the opposite: practical reforms depend on utopian dreaming. It encourages us in our efforts, and sets a beacon in the uncharted seas of the distant future, and in doing so drives to incremental improvements. The world needs utopia, as the cities and mansions that people dream of are those in which they finally live.

For as long as we exist, we have imagined the things that ought to be. The Greeks knew such wise men as philosophers, they allowed them great freedom and rejoiced in the mathematical precision with which their intellectual leaders mapped out those theoretical roads which were to lead mankind from chaos to an ordered state of society. The Old Tes tament used to call such people prophets, insisting with narrow persistence upon the King dom of Heaven as the only possible standard for a decent Christian Utopia. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries fought many bitter wars to decide the exact nature of a white- washed Paradise, erected upon the crumbling ruins of the medieval church. The eighteenth century saw the Promised Land lying just across the terrible bulwark of stupidity and super stition, which a thousand years of clerical selfishness had erected for its own protection and safety. There followed a mighty battle to crush the infamy of ignorance and bring about an era of well-balanced reason. Unfortunately, a few enthusiasts carried the matter a trifle too far. Napoleon, realist-in-chief of all time, brought the world back to the common ground of solid facts. In response, the twentieth century grew a counter-culture of everything fixed and finite, and presented utopia with its twin brother, the anti-utopia, which by opposing utopia also made her stronger. But in recent decades something has changed. Many observe utopia and their sympathizers as foolhardy dreamers at best and murderous totalitarians at worst. If the utopian spirit has proved to be a tool to trigger progress and improvements, then the recent growing suspicion towards utopia and the growing anti-utopian library is worrisome. Over the last century Utopia has gained a historic record of “anti-utopian” novels and instead of worrying how we can get to the good place we now think about how we can prevent the ‘utopian project’ from being realized. How did this happen? And as the will-to- transcend will always remain, how can we make the utopian project, our beacon leading us to conscious progress and change, legitimate and valuable again?

Understanding where utopia stands today is to understand its past, where it comes from and what ideas it carried. The first part of this thesis is an attempt to set out, mainly in drawing, supported by text, the general pattern of utopian writing in the West. Setting out the history of utopian writing is not meant principally as an historiographical exercise, but is necessary for understanding and thinking about the fate of utopia in our own times, and its possibilities for the future. Through history we learn how utopia always emerges and exists under specific circumstances. At the same time, the content and articulation of utopia has always been bonded to a set of attributes such as the organization of knowledge; power; the interpretation of territory; and time, resulting in the question of finality. Understanding the changing utopian tradition as a result of the changing attributes of the material world in the past, can help us understand the recently emerged suspicion of the utopia today, and hand us the tools to resonate on the possibility of a post-modern utopia tomorrow.

An inevitable part of the utopian tradition is the art of storytelling, and therefor, this elab- oration on the changing tradition of the utopia of the west is done mainly through image and illustrated with words. Image 1. History of the Utopian tradition, shows an overview of the whole story. Our journey begins in ancient Greece, with the Republic of Plato, as we work ourselves up to the utopian visions of the 20th century. A sequence of fragments, taken from the main image, will guide us through the story, handing us the possibility to not only understand each utopia as a separate entity or a product of its time, but also to understand each story as a part of a changing utopian tradition.

[…] Ch. 1 – Ch. 7 are left out but are available in print.

- Al-Farabi’s Humanistic Principles and “Virtuous City”

by Anar Tanabayeva

In our time of globalization humanistic principles should be fundamental to the people around the world, otherwise we can not solve the global problems of mankind. At the present time, when the world globalization processes put before mankind new issues and identified the main problem, the study of the works of such thinker as Al-Farabi becomes extremely important. To study Al-Farabi’s philosophy is becoming more relevant in today’s context of increasing democratic reforms, creation of a legal, secular state and approval of harmony in society. In this respect, the study of political philosophy of Al-Farabi, especially his teachings on politics, freedom, happiness, and the need to mutual assistance between people, his appeal to science, intellectual and moral perfection of man and society, over-actualized. Particularly relevant today a thinker’s concept on political leadership, his ideas about the virtuous society, justice, equality, preserving peace, preventing war, condemnation of wars. In this regard, political philosophy and ideas of the thinker can be a valuable source for the education of the younger generation. Read more here

- Utopian Literature of the Ideal Society: A Study in Al-Farabi’s Virtuous City & More’s Utopia

Utopian literature in its broadest meaning deals with the idealistic conceptions and themes that are not applicative in real human life. This type of literature and thinking,

though we regard it as imaginative and may be fanciful, yet it embodies great themes, and aiming at noble human goals and purposes.

Al-Farabi in his work the Virtuous City and More in his Utopia present to the humanity through these two magnificent works, under discussion in this research, an example of the virtuous and idealistic community they aspire, as philosophers, to be achieved in real human life, if virtue and goodness guide mankind to its perfection and happiness.

This research discusses these two works as Utopian literature, irrespective to the profound philosophical thoughts they comprise. Read more here

- AL-FARABI ON THE DEMOCRATIC CITY

This essay will explore some of al-Farabı’s paradoxical remarks on the nature and status of the democratic city (al-madı¯nah al-jamaıyyah). In describing this type of non-virtuous city, Farabı departs significantly from Plato, according the democratic city a superior standing and casting it in a more positive light. Even though at one point Farabı¯ follows Plato in considering the timocratic city to be the best of the imperfect cities, at

another point he implies that the democratic city occupies this position.

Since Farabı’s discussion of imperfect cities is derived from Plato’s Republic and follows it in many important respects, I will argue that his departure from Plato in this context is significant and points to some revealing differences between the two philosophers. In order to demonstrate this, I will first set up a comparison between Plato’s conception of the democratic city and Farabı’s. Then I will propose three explanations for the greater appreciation that Farabı seems to have for democracy, as well as for the apparent contradiction in Farabı’s verdict concerning the second best city. Read more here

- Al-Farabi’s doctrin: virtuous people and a model of the «perfect man»

On the basis of reasonable activity of a man as his natural prop- erties Al-Farabi made a

number of conclusions about the humanistic equality of all people as a result of the overall reasonable nature of the autonomy of the human being, the creative activity of the person, freedom of the human will, independent of the value of human life. This issue Al-Farabi considered in his «Treatise on the views of the residents of the virtuous city».

Perfect society of Al-Farabi divides into three types: the great, medium and small. Great Society – a collection of companies of all people living in the land, the average – an association of people in some parts of the land, small-a small association of residents.

The greatest good and the highest perfection can be achieved, according to al-Farabi,

primarily the city, but not society, standing on the lower level of perfection. The latter AlFarabi considers the village, district, street and house. This system is a perfect society, drawn by Al-Farabi with strict logical sequence is the result of logical thinking scientist coming from the relationship between the concepts of general and private.

So, the most perfect form of society, by Al-Farabi, is the city. He uses the term city not only represents the city in the modern sense, as a unit of administrative-territorial division, but also to refer to the state and social groups.

An important place in the social and ethical teachings of Al- Farabi is the idea of a

virtuous city. Virtue, according to Al-Farabi, – this is the best moral qualities. Read More here

- THE ISLAMIC CONCEPT OF HUMAN PERFECTION*

William C. Chittick

The name `Islam’ refers to the religion and civilization based upon the Qur’án, a Scripture revealed to the Prophet Muhammad in the years AD 610-32. About one billion human beings are at least nominally Muslim, or followers of the religion of Islam. The modern West, for a wide variety of historical and cultural reasons, has usually been far less interested in the religious dimension of Islamic civilization than in, for example, that of Buddhistn or Hinduism. Recent political events have brought Islam into contemporary consciousness, but more as a demon to be feared than a religion to be respected for its sophisticated understanding of the human predicament.

Those few Westerners who have looked beyond the political situation of the countries where Islam is dominant have usually devoted most of their attention to Islamic legai and social teachings. They quickly discover that Islam, like Judaism, is based upon a Revealed Law, called in Arabic the Shari’a or wide road. Observance of this Law — which covers such domains as ritual practices, marriage relationships, inheritance, diet and commerce —is incumbent upon every Muslirn. But western scholars have shown far less interest in two other, more inward and hidden dimensions of the Islamic religion, mainly because these have had few repercussions on the contem-porary scene. Even in past centuries, when Islam was a healthy and flourishing civilization, only a relatively smalt number of Muslims made these dimensions their tentral concern.

Those few Westerners who have looked beyond the political situation of the countries where Islam is dominant have usually devoted most of their attention to Islamic legai and social teachings. They quickly discover that Islam, like Judaism, is based upon a Revealed Law, called in Arabic the Shari’a or wide road. Observance of this Law — which covers such domains as ritual practices, marriage relationships, inheritance, diet and commerce —is incumbent upon every Muslirn. But western scholars have shown far less interest in two other, more inward and hidden dimensions of the Islamic religion, mainly because these have had few repercussions on the contem-porary scene. Even in past centuries, when Islam was a healthy and flourishing civilization, only a relatively smalt number of Muslims made these dimensions their tentral concern.

The more hidden dimensions of Islam can be called `intellectuality’ and `spirituality’. The first deals mainly with the conceptual understanding of the human situation and the second with the practical means whereby a full flowering of human potentialities can be achieved. They are important in the present context because they provide clear descriptions of human perfection and set down detailed guidelines for reaching it. If we want to discover how Islam has understood the concept of perfection without reading our own theories into the Queán or imposing alien categories on the beliefs and practices of traditional Muslims, we have to pose our question to the intellectual and spiritual traditions of Islam itself. Read more Here

- An Analysis of Ibn al-‘Arabi’s al-Insan al-Kamil, the Perfect Individual,

with a Brief Comparison to the Thought of Sir Muhammad Iqbal by Rebekah Zwanzig,

This thesis analyzes four philosophical questions surrounding Ibn al-‘Arabi’s concept of the al-insan al-kamil, the Perfect Individual. The Introduction provides a definition of Sufism, and it situates Ibn al-‘Arabi’s thought within the broader context of the philosophy of perfection. Chapter One discusses the transformative knowledge of the Perfect Individual. It analyzes the relationship between reason, revelation, and intuition, and the different roles they play within Islam, Islamic philosophy, and Sufism. Chapter Two discusses the ontological and metaphysical importance of the Perfect Individual, exploring the importance of perfection within existence by looking at the relationship the Perfect Individual has with God and the world, the eternal and non-eternal. In Chapter Three the physical manifestations of the Perfect Individual and their relationship to the Prophet Muhammad are analyzed. It explores the Perfect Individual’s roles as Prophet, Saint, and Seal. The final chapter compares Ibn al-‘Arabi’s Perfect Individual to Sir Muhammad Iqbal’s in order to analyze the different ways perfect action can be conceptualized. It analyzes the relationship between freedom and action.

1) what type/s of knowledge are necessary to gain a complete understanding of the eternal and non-eternal, and how this transformative knowledge leads to perfection;

2) The Perfect Individual as a level of existence, and how the individual fits into the dichotomy of eternal and non-eternal;

3) The Perfect Individual as a reflection of the Divine in the cosmos, or what the transformation and embodiment of perfection entails;

4) the Perfect Individual as an active agent in the world, and how this individual, after reaching perfection, interacts with the world. Some of the problems that will arise in the proceeding chapters and the proposed solutions are outlined below. Read more here

- On the Relation of City and Soul in Plato and Alfarabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Alfarabi, the medieval Muslim philosopher and the founder of Islamic Neoplatonism, is best known for his political treatise, Mabadi ara ahl al-madina al- fadhila (Principles of the Opinions of the Inhabitants of the Virtuous City), in which he proposes a theory of utopian virtuous city. Prominent scholars argue for the Platonic nature of Alfarabi’s political philosophy and relate the political treatise to Plato’s Republic. One of the most striking similarities between Alfarabi’s Mabadi ara ahl al-madina al- fadhila and Plato’s Republic is that in both works the theory of virtuous city is accompanied by a theory of soul. It is true that Alfarabi’s theory of soul differ considerably from that of Plato’s Republic. However, we propose that notwithstanding the differences, the two theories of soul do play an identically important role in the respective theory of virtuous city. The present article explores the relationship between the soul and the city in Plato’s Republic and Alfarabi’s Mabadi ara ahl al-madina al- fadhila, and intends to show that in both works the coexistence of the theory of soul and the city is neither coincidental nor a casual concurrence of two themes. Rather, the

concept of soul serves as a foundation on which Plato and Alfarabi erect their respective theory of perfect association. Thus, Alfarabi’s treatise resembles Plato’s Republic not only in the coexistence of the theory of soul and the city, but also in the important role of the concept of soul in the theory of virtuous city. Read more here

- SEVEN LEVELS OF BEING

“The secularity of the society in which we live must share considerable blame in the erosion of spiritual powers of all traditions, since our society has become a parody of social interaction lacking even an aspect of civility. Believing in nothing, we have preempted the role of the higher spiritual forces by acknowledging no greater good than what we can feel and touch.” Vine Deloria Jr

The perspective of modernity where Western Man as the egolatrous being is placed at the top of existence for all others to look towards for recognition.

The pyramidal construction of Man from an Islamic perspective shifts our understanding of the seriousness of placing the egolatrous Man above God in constructing reality, while simultaneously allowing us to imagine what would be necessary in creating a transmodern critique in constructing the Human.

THE ISLAMIC CONCEPT OF HUMAN PERFECTION:

Those dimensions of Islam dedicated to providing the guidelines for the development of the full possibilities of human nature came to be institutionalized in various forms. Many of these can be grouped under the name `Sufism’, while others can better be designated by names such as `philosophy’ or `Shiite gnosis’. In general, these schools of thought and practice share certain teachings about human perfection, though they also differ on many points. Here we can suggest a few of the ideas that can be found in most of these approaches.

Those dimensions of Islam dedicated to providing the guidelines for the development of the full possibilities of human nature came to be institutionalized in various forms. Many of these can be grouped under the name `Sufism’, while others can better be designated by names such as `philosophy’ or `Shiite gnosis’. In general, these schools of thought and practice share certain teachings about human perfection, though they also differ on many points. Here we can suggest a few of the ideas that can be found in most of these approaches.

Look also: Polishing your heart, Virtues Ethic for a modern Devotion in our times

Look also: Polishing your heart, Virtues Ethic for a modern Devotion in our times

Current decadence, greed, evil, falsehood, corruption, violence, injustice, exploitation, thus have a Cosmic undertone. It is a “Cosmic Law” that civilizations which have become megalomaniacal will inevitably collapse. Because all levels of existence are corroded – including the religious realm – only a Dimension that is beyond can redeem us.

One of the many disastrous consequences of an ongoing repression of this trans-personal Ground of Being – and the mistaken assumption of the Absolute by a relative entity or self – is epitomized in our techno-industrial pursuit to convert the earth into one large global factory – reinforced by multinational monopoly. Herein, nature is viewed simply as exploitable “raw material” for a “manufacturing” process aimed at churning out “products” for the “consumer.” This apparent narrowing of human perspective is the logical result of paradigmatic trends linking back to the so-called Age of Enlightenment.

- SEVEN LEVELS OF BEING(NAFS)

The first verses regarding Jihad were revealed in Makkah before the Hijra to Medina. These verses reference “Jihad al-Nafs” or the struggle against the self (ego/ base desires)

- Al GHAZALI ON JIHAD AL-NAFS [FIGHTING THE EGO] )

Meaning of nafs: It has two meanings.

First, it means the powers of anger and sexual appetite in a human being… and this is the usage mostly found among the people of tasawwuf [sufis], who take “nafs” as the comprehensive word for all the evil attributes of a person. That is why they say: one must certainly do battle with the ego and break it (la budda min mujahadat al-nafs wa kasriha), as is referred to in the hadith: A`da `aduwwuka nafsuka al-lati bayna janibayk [Your worst enemy is your nafs which lies between your flanks. Al-`Iraqi says it is in Bayhaqi on the authority of Ibn `Abbas and its chain of transmission contains Muhammad ibn Abd al-Rahman ibn Ghazwan, one of the forgers].

The second meaning of nafs is the soul, the human being in reality, his self and his person. However, it is described differently according to its different states. If it assumes calmness under command and has removed from itself the disturbance caused by the onslaught of passion, it is called “the satisfied soul” (al-nafs al-mutma’inna)… In its first meaning the nafs does not envisage its return to God because it has kept itself far from Him: such a nafs is from the party of shaytan. However, when it does not achieve calmness, yet sets itself against the love of passions and objects to it, it is called “the self-accusing soul” (al-nafs al-lawwama), because it rebukes its owner for his neglect in the worship of his master… If it gives up all protest and surrenders itself in total obedience to the call of passions and shaytan, it is named “the soul that enjoins evil” (al-nafs al-ammara bi al-su’)… which could be taken to refer to the ego in its first meaning.

From the beginning of our entrance into the school of Sufism, we have been taught about the seven levels of being. These seven levels are like grades in any educational system which one must pass through in order to graduate. In our system, however, evaluations are made by a Higher Authority than the teacher.

Passing and failing grades are made known through real dreams, through the interpretation of which the teacher gives new responsibilities and duties to the seeker. But what is most important is that the seeker himself should be able to realize his own states so that he can live up to the next level to which he aspires. Obviously, first it is necessary that he be conscious, aware of his character and actions, and be sincere in looking at himself. But it is also necessary to thoroughly know the characteristics of each level, especially the level in which he is presumed to be, and the next level, in which he hopes to be. Read more here

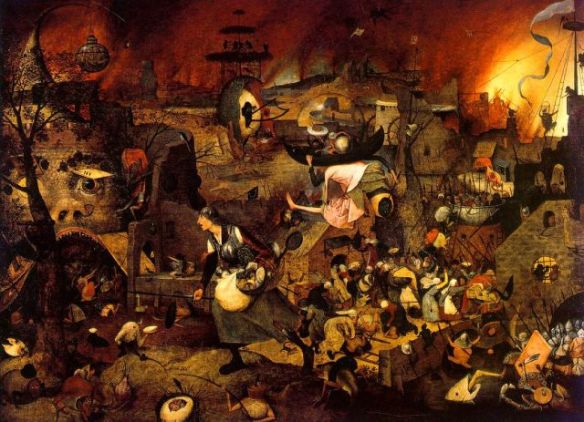

- To See Yourself within It: Bruegel’s Festival of Fools

by Todd Marlin Richardson

Bruegel’s Festival of Fools

The topics of blindness and self-awareness I discussed in relation to the

Peasant and Nest Robber bring me to the focus of my fourth and final chapter,

Bruegel’s Festival of Fools . In addition, the practices of making and viewing

works of art I have described for all of Bruegel’s later peasant paintings are also

helpful in thinking about this particular design. Nadine Orenstein argues for a late

dating of the print, after the now lost drawing by Bruegel, based on the words Aux

quatre Vents inscribed at the bottom center. This is the form of the publisher’s address

used by the widow of the print’s publisher, Hieronymus Cock, following his death in

1570. Orenstein speculates the drawing was completed in the last years of Bruegel’s

life, during the same time he painted the peasant panels, and the print produced after

his death.

Although fairly subtle, the composition of the Festival of Fools stages a

procession similar to a wagon play. (Wagon plays were processional dramas that took place during Ommegangen (devotional processions) in the 1550s and 1560s. Rhetoricians conceived of wagon plays as didactic episodes that could morally

edify and educate their audience. The plays utilized overt metaphors and personifications to create allegorical productions that focused on collective civic identity. Read more here

- The Choice for Spiritual Ethics,Virtues and Uprightness in our times

The bivium of Pythagoras, this sign which leaves us free to choose the path of good or the path of evil.

The bivium of Pythagoras, this sign which leaves us free to choose the path of good or the path of evil.

“The letter” Y “represents the symbol of moral life. The question of good and evil arises before the free will of man: two roads open before him: the left, the thick branch of the “Y”, is wide and easy to access, but leads to the chasm from shame, that of the right, the thin branch, is a steep and painful path, but at the summit of which one finds repose in honor and glory. “

- Note: Parallels are often drawn between this work and John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress.[2]

The letter “Y”, in antiquity, has often represented a “bivium” (a fork in the road); a point in life where we have to make a vital decision. According to Pythagoras, it represents the paths of virtue and vice. The letter Y is also symbolic of looking within, Inner contemplation, Meditation and inner wisdom.

The letter “Y”, in antiquity, has often represented a “bivium” (a fork in the road); a point in life where we have to make a vital decision. According to Pythagoras, it represents the paths of virtue and vice. The letter Y is also symbolic of looking within, Inner contemplation, Meditation and inner wisdom.

- To Become a “Refugee”: Emigration to Sincerity or “uprightness” of Love

What the Emigration to Sincerity demands of us

Emigration: Historical Hijra

Starting from a narrow family-tribal environment Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) underwent 13 years of hardship and torment in Meccan society; with the immigration (Hijra) to Medina, a new stage began. This stage, if one takes into consideration the time that it took all religions to spread, is the starting point of one of the fastest religious developments in recorded history. In this sense, when one speaks of the Hijra one is not merely speaking of a journey from Mecca to Medina, or the starting point of a calendar; one is speaking of a new start for humanity.

The Hijra is symbolic of changing those conditions that cause problems and that clash with ideals and beliefs, as well as the search for new opportunities. ..

…The most important principle to learn from the Hijra is the constant observation of intention. In particular, Sufis consider the constant observation and control of intent to be a basic principle for attaining ikhlas (sincerity). From this aspect, Sufism can be considered to be a total investigation and interrogation of intention.

Goethe and his poem “Hegir” : Hijra

When one speaks of the Hijra one is not merely speaking of a journey from Mecca to Medina, or the starting point of a calendar; but one is also speaking of a new start for humanity. And Johann Wolfgang von Goethe make his Hijra, his emigration and take refuge in Islam. He became a “Refugee”.

The Hijra is symbolic of changing those conditions that cause problems and that clash with ideals and beliefs, as well as the search for new opportunities.

In this caravan poem, Goethe gives us a picture of the restless nomad existence which early Arabian poetry had enabled him to envision.

The whole “West-East Divan” is shot through with something of this nomadic restlessness. Already in the first great poem entitled “Hegir” the poet alludes to Arabian life and traditions. He is a True Pelgrim. He turns to the wisdom of the Sufis as Hafiz.

His own “Hedschra” is an inteliectual emigration to a simpler state of existence which seems to him to be purer and righter than his own immediate world. Thus he calls out to himself:

“Hegira”

North and South and West are quaking,

Thrones are cracking, empires shaking;

Let us free toward the East

Where as patriarchs we’ll feast:

There in loving, drinking, singing

Youth from Khidr’s well is springing.

His goal: to discover and reconcile in himself in a new, higher unity the multiplicity of monotheism’s divine expressions. Such unity was always Goethe’s goal, for he well understood the alchemical truth that unity only divides in order to find itself again in a higher sense. As he wrote:

Anything that enters the world of phenomena must divide in order to appear at all. The separated parts seek one another again, and may find each other and be reunited: in the lower sense by each mixing with its opposite, that is, by simply coming together with it, in which case the phenomenon is nullified or at least becomes indifferent. But the union can also occur in the higher sense, whereby the separated parts are first developed and heightened, so that the combination of the two sides produces a third, higher being, of a new and unexpected kind. Read more here

Anything that enters the world of phenomena must divide in order to appear at all. The separated parts seek one another again, and may find each other and be reunited: in the lower sense by each mixing with its opposite, that is, by simply coming together with it, in which case the phenomenon is nullified or at least becomes indifferent. But the union can also occur in the higher sense, whereby the separated parts are first developed and heightened, so that the combination of the two sides produces a third, higher being, of a new and unexpected kind. Read more here

The Babylonian Tower of Modernity

- The Babylonian Tower of Modernity

By Carlijn kingma CARTOGRAPHY OF SOCIETY

How our religion of capitalism and central believe in mechanical progress has led again to confusion of speech, and how society, accordingly, ends up divided in multiple romantic reactions. Or, a map to find our way home within the modern dream of progress.

In collaboration with Piet Vollaard and Edwin Gardner

Rotterdam 2017

Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves; otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth.”

— Genesis 11:4

Why does a man build a tower? To fight off enemies? To transmit TV programs? To house more inhabitants and to economize high costly earth? No, no and no! That’s a lie, and the masking of the real and the only true function of a Tower – to shout as loud as possible “Here I am! Look how strong and mighty I am!

This time we are building a tower to reach for the heavens of progress. Organized around an oil engine, we deploy, we produce and continue to grow. But somehow along the way, dissonance emerged on the exact direction we are heading. And while trying to reach for these heavens of progress, we forgot why we actually wanted to go there in the first place. And once we finally reach the skies, our sight is clouded with smog.

Almost everyone inside the tower – or maybe even everyone – secretly dreams of being better. To be smarter, richer, more liked or more powerful. And in order to become this better person, and move up inside the hierarchy of our society, a man will face competition. Most of us get stuck somewhere in some layer of accomplishments/success, but for the lucky little few, who can make it to the top, the world beneath is a playground.

But first of all, down in the center of the drawing, to be able to enter the tower at all, a man has to have the right papers. Like the lottery you can win a ticket for access, if born in the right country at the right time. If not, we are very sorry to tell you, but I’m afraid today we are full. But if you happen to win and you have made it inside, you can walk the ramps, that circle up, and eventually aim for the skies. But again, like everything else in this world, not without resistance.

Inside the tower, at the bottom of it all, we find the working class. We call them the lower educated, and they perform practical tasks, such as taking the oil from the earth. To transcend and move up inside the tower of success, perhaps to the service based practices, you need first to pass through an educational gate, to prove you are worthy of the task. But to reach for the skies, it doesn’t stay there, there are multiple thresholds and gates. Although the gates of global borders now seem permanently open, you will soon walk upon some more, judging your ethnical background, your gender and family name. And finally, for the engineers and programmers who work inside the building for bigger trade, to become a god in our own little world, to become director of the the political muppet show and to rule, point and divide, there is a gate to pass only with money.

— view here ( in Dutch)

It all might seem unbelievable maybe, but don’t think for a moment we are non-believing men. For all I know there is much and more to say about our central believe in mechanical progress. We have gods of progress to turn to and to worship. Zeus, with his pointy arrow in arm, ripped right of the growth chart. Or Hermes, playing an arithmetic song about how we can reach for the innumerable/uncountable.

Imprisoned within the eternity of our daily routines, in fear of losing our spot in the line to another person or to a robot perhaps, we solemnly move from one task to the next. In blind procession, trying to keep the engine of capitalism running and do what is expected of us, we have all become creatures of habit and convention.

We work eight hours, we sleep eight hours, and in the eight hours left we work a little more. While night we secretly dream of descending, up to nobody knows where. Inside our man made dream of housing, we happily decorate the concrete cells like cabinets of homely attributes. But somehow, everywhere within the tower, from the exiled migrant to the footloose networker, people have lost their notion of home. Our bedrooms become a product on the market, while work has been move to the kitchen table. Home has been displaced by an idea that’s both elusive and contested. And we feel lost and displaced inside this rational concrete dream.

Note: The Tower of Babel by Breughel

Building the Tower of Babel was, for Dante, an example of pride., Canto 12.

Purgatory in the poem of Dante Divine Comedy is depicted as a mountain in the Southern Hemisphere, consisting of a bottom section (Ante-Purgatory), seven levels of suffering and spiritual growth (associated with the seven deadly sins), and finally the Earthly Paradise at the top. Allegorically, the Purgatorio represents the penitent Christian life In describing the climb Dante discusses the nature of sin, examples of vice and virtue, as well as moral issues in politics and in the Church. The poem outlines a theory that all sins arise from love – either perverted love directed towards others’ harm, or deficient love, or the disordered or excessive love of good things.

The gate of Purgatory, Peter’s Gate, is guarded by an angel bearing a naked sword, his countenance too bright for Dante’s sight to sustain. In reply to the angel’s challenge, Virgil declares that a lady from heaven brought them there and directed them to the gate. On Virgil’s advice, Dante mounts the steps and pleads humbly for admission by the angel, who uses the point of his sword to draw the letter “P” (signifying peccatum, sin) seven times on Dante’s forehead, bidding him “take heed that thou wash / These wounds, when thou shalt be within.”

With the passage of each terrace and the corresponding purgation of his soul that the pilgrim receives, one of the “P”s will be erased by the angel granting passage to the next terrace. The angel at Peter’s Gate uses two keys, silver (remorse) and gold (reconciliation) to open the gate – both are necessary for redemption and salvation. As the poets are about to enter, they are warned not to look back. Read more here

World on Fire

In his essay “World on Fire” Charles Eisenstein describe the situation as follow:

“I can’t easily draw a causal connection here, but it seems significant that uncontainable wildfires are contemporaneous with inflammatory rhetoric, heated debates, flaring tempers, burning hatred, seething distrust, and smoldering resentment. Just as dried out, fuel-laden forests burned out of control with a mere spark, so also have our cities burned as the spark of police murders touched the ready fuel of generations of racism; decades of economic decay, and months of Covid confinement. Our social ecosystem is as damaged and depleted as the forests that are so prone to fire“.

- Reverence and Relationship

While engineers, ecologists, and especially indigenous people can offer techniques to properly steward forests and restore them to resiliency, the transition to a healed world requires something much deeper than better techniques. More important is to learn to inhabit the source from which indigenous land stewardship practices arise. That source is a way of seeing, conceiving, and relating to nature. It is also a way of understanding ourselves: who we are and why we are here.

Fundamentally, the source of wise forest management is to see and know nature as a being, not a thing. That’s the best I can put it, but it isn’t good enough. The words themselves entrap me in error. Nature is not something separate from ourselves, and not even “things” are just things. Let me say then that traditional and indigenous cultures live in a world where being is everywhere and in everything, and humans are no more or less sacred than trees, mountains, water, or ants.

On the most obvious level, the view of nature-as-thing greatly facilitates the clearcutting, mining, stripping, and profiteering, just as dehumanization of other people allows their exploitation and enslavement. It’s the same basic mindset. But there is another problem too: the mindset of nature-as-thing prevents us from coming into the intimacy of relationship that is necessary to tend, heal, and cocreate with it to mutual benefit. It is like the difference between a doctor who treats you impersonally, as a “case,” and one who sees you as a full human being.

Last month, the state of California committed to a 20-year program of forest thinning which seeks to reduce fires through brush clearing, logging, and prescribed burns. This program is fraught with possible unintended consequences. When we understand a forest as an organism, a being, rather than an engineering object, we recognize engineering concepts like reducing fuel load as, at best, a first step. After all, a healthy forest requires rotting vegetable matter to nourish fungi, invertebrates, etc. that are crucial elements of forest ecology. How do we know how much brush to clear and how many logs to remove? We can only learn that through attentive observation and long relationship. Here, the experience of local first peoples can be invaluable, as they have built up that knowledge over countless generations. To learn from the inevitable mistakes that will occur in the forest thinning program will require humility, the kind that comes when one knows one is relating to a complex living being. Otherwise, we stumble from one error to the next, as when, in an effort to increase carbon sequestration, we plant ecologically and culturally unsuitable trees that end up dying a few decades later, leaving conditions even worse than before.

Another word for the attitude that I named as the source from which indigenous land stewardship practices arise is “reverence.” To revere something is the opposite of reducing it to a thing. Modern, educated people have long lived in an ideological matrix that says nature, at bottom, is merely a whirl of generic particles bumping around according to mathematical forces. What is there to revere? It says that purpose, intelligence, and consciousness subsist in human beings alone. The burning of the world calls us to awaken from this delusion.

From the attitude of reverence, we see things invisible to the engineer’s eye. We ask questions the utilitarian never asks. Paradoxically, in the end, the knowledge thus gained we be more useful – not just to the forest, but to ourselves – than anything we could accomplish from the exploitative mindset.

In truth, we are not separate from nature. What we do to the other, we ultimately do to ourselves. When the forests are sick, we are sick. When they burn, even if we escape the flames, something burns within us too. The social climate mirrors the geological climate. We may not recognize this truth as indigenous people do, but we are the land. Is it not obvious, looking at today’s political landscape, that a fire rages out of control?

I can’t easily draw a causal connection here, but it seems significant that uncontainable wildfires are contemporaneous with inflammatory rhetoric, heated debates, flaring tempers, burning hatred, seething distrust, and smoldering resentment. Just as dried out, fuel-laden forests burned out of control with a mere spark, so also have our cities burned as the spark of police murders touched the ready fuel of generations of racism; decades of economic decay, and months of Covid confinement. Our social ecosystem is as damaged and depleted as the forests that are so prone to fire.

The matrix of complex relationships that we call community has to a great degree collapsed into simplified relations with impersonal institutions, mediated by money and technology. Social networks may give the appearance of community, but they lack the interdependency that marks a real community (or ecosystem). We can see now how fragile – or how inflammable – such a society is.

I won’t be so bold as to say that addressing our social separation will quell the fires. Yet, one can see how the project of land healing through reverence and relationship is congruent to the project of social healing, which, too, depends on restoring reverence and relationship.

———————————–

Note: Compare with 500 years ago:

Bruegehel : the Apocalypse within

The absurdity of Bruegel’s characters comes straight out of Erasmus’ Praise of Folly, a fantasy and satire on the self-deception on much of human endeavour, mocking human pretensions, monks and theologians, the scholastic intellectual substructure that supported late Medieval piety.

Erasmus cites Democritus who was supposedly constantly amused by the spectre of humanity. The book first appeared in 1511, and underwent numerous revisions and additions until the last corrections in 1532. It was an instant success. The book’s narrator is Folly who portrays life as an absurd spectacle lambasting the foibles and frailties of mankind, only to praise the ‘folly’ of simple Christian piety, the pious ideals in which Erasmus had been educated, and spirituality of The Imitation of Christ, four treatises from the 15th century attributed to Thomas â Kempis.

Erasmus and À Kempis were both Augustinian canons, more importantly both had their roots in the devotio moderna to which Erasmus remained faithful to the end of his life.

The text of Folly is a potent mix of wit, wisdom and wordplay, but it culminates in a serious indictment of churchmen, and sets out the virtues of a Christian way of life that St Paul says looks to the world like folly: “For Christ sent me not to baptize, but to preach the gospel: not in wisdom of speech, less the cross of Christ should be void. For the word of the cross, to them indeed that perish, is foolishness; but to them that are saved, that is, to us, it is the power of God”.

This is the crossroads of belief where Renaissance Christianity and Medieval religion collide, and evangelical humanists take the turning signposted scripture. The pilgrim’s way had forked and despite the lure of side roads such as ‘theological backlash’ and ‘millenarianism’, two major routes had opened up, and remained open, to choose from.

Bruegel stood at that crossroads and seemed never quite made up his mind which direction to go in. As he wavered in his decision, he was also sensibly never open about exactly what he believed. “He lived at a time and place in which free and open expression of certain ideas could mean death.” Read more here

————————————–

The Doorway Called Enchantment

I live in the northeast of the land people call the United States. Here, fire is not much of a threat, yet. A few weeks ago I was walking with my brother in the woods behind his Pennsylvania farm, where the sloping land gives way to mountainside. We crossed a creek, a bare trickle in some places, dry in others. John told me that he had been here with an old-timer who said that in his youth, this creek was so deep and strong, even in August, that there were only a few places one could cross it. What happened to this being, this creek? Some locals say it is because too many wells were dug, drawing down the water tables and drying out the springs that feed the creeks. Others say it is because of the repeated logging of the mountain, going back to colonial times. Or maybe, I thought, it is again a long-delayed result of the cascade of changes following the extermination of wolves, cougars, and beavers. All these activities are an insult to the land and to the water, oblivious to reverence.

Ultimately, to stop the fires and turn onto a world-healing path, we must turn from domination and subjugation to reverence and respect. Sometimes that means adopting the role of a protector for vulnerable, precious beings, like Marina Silva is doing in Brazil. (Here is an organization she works with, along with others I mentioned in my 2019 article on the Amazon fires.) Sometimes it means stepping into the role of nurturer or healer, like the people reintroducing beavers, practicing regenerative agriculture, and building water retention landscapes. For someone in the corporate or financial world, reverence might steer them to choose life over profit in a moment where it takes a little courage to do that. That courage is a dilute version of the courage of South American indigenous activists who risk torture and murder by landowners, logging companies, mining companies, and their paramilitaries, because it puts something else above maximizing personal self-interest. It is thus an important act of solidarity.

Reverence brings courage. Reverence brings knowledge. Reverence brings skill. Reverence brings healing. It is the fulcrum of the great turning of civilization toward reunion with nature. Today the word has religious connotations, but this is not the kind of reverence that worships an idol. It is the reverence of the lover who looks into the eyes of the beloved and sees infinity.

If reverence brings all these things, then what brings reverence? It will not do merely to exhort people to be more reverent. The gateway to reverence is enchantment. A few days ago I stood with my son Cary, age seven, at Rhode Island’s last undeveloped coastal pond watching turtles. We felt what it was like to be those turtles. We could hardly stop watching them. In that moment, the thought that we would harm them for anything less than a sacred purpose was horrifying and absurd. We knew them as precious in and of themselves, not for any use to us. Few people, dropping into that moment, could escape that enchantment. Yet, every day, we participate in systems that treat turtles and much else as resources to exploit, or make them collateral damage in other exploitation. We cannot avoid this participation, for we live in that system, and that system lives in us. More and more of us no longer feel at home in it though. It cannot easily accommodate our reverence, our enchantment, and our true purpose of service to life.

Mining company executives or members of ranchers’ death squads might be far away from the doorway of enchantment. The principle of enchantment-borne reverence does not substitute for legal action, nonviolent direct action, and so on. However, a healed planet will not result from a succession of desperate holding actions. We need to ground ourselves in directly experiencing earth as obviously precious as the turtles were to Cary; to know her as a being and as an organism, and we need to spread that knowledge. Then we will have the clarity, the courage, the skill, and most importantly, the allies in unlikely places, to defend her vulnerable parts, to preserve and strengthen her organs, and to transition away from systems built on the mythology of earth-as-thing.

Note: The Tower of Babel by Breughel

Building the Tower of Babel was, for Dante, an example of pride., Canto 12.

Purgatory in the poem of Dante Divine Comedy is depicted as a mountain in the Southern Hemisphere, consisting of a bottom section (Ante-Purgatory), seven levels of suffering and spiritual growth (associated with the seven deadly sins), and finally the Earthly Paradise at the top. Allegorically, the Purgatorio represents the penitent Christian life In describing the climb Dante discusses the nature of sin, examples of vice and virtue, as well as moral issues in politics and in the Church. The poem outlines a theory that all sins arise from love – either perverted love directed towards others’ harm, or deficient love, or the disordered or excessive love of good things.

The gate of Purgatory, Peter’s Gate, is guarded by an angel bearing a naked sword, his countenance too bright for Dante’s sight to sustain. In reply to the angel’s challenge, Virgil declares that a lady from heaven brought them there and directed them to the gate. On Virgil’s advice, Dante mounts the steps and pleads humbly for admission by the angel, who uses the point of his sword to draw the letter “P” (signifying peccatum, sin) seven times on Dante’s forehead, bidding him “take heed that thou wash / These wounds, when thou shalt be within.”

With the passage of each terrace and the corresponding purgation of his soul that the pilgrim receives, one of the “P”s will be erased by the angel granting passage to the next terrace. The angel at Peter’s Gate uses two keys, silver (remorse) and gold (reconciliation) to open the gate – both are necessary for redemption and salvation. As the poets are about to enter, they are warned not to look back. Read more here