- OF MUMMERS AND MEN in Bulgaria

In the midst of winter, kukeri dance for the rebirth of nature

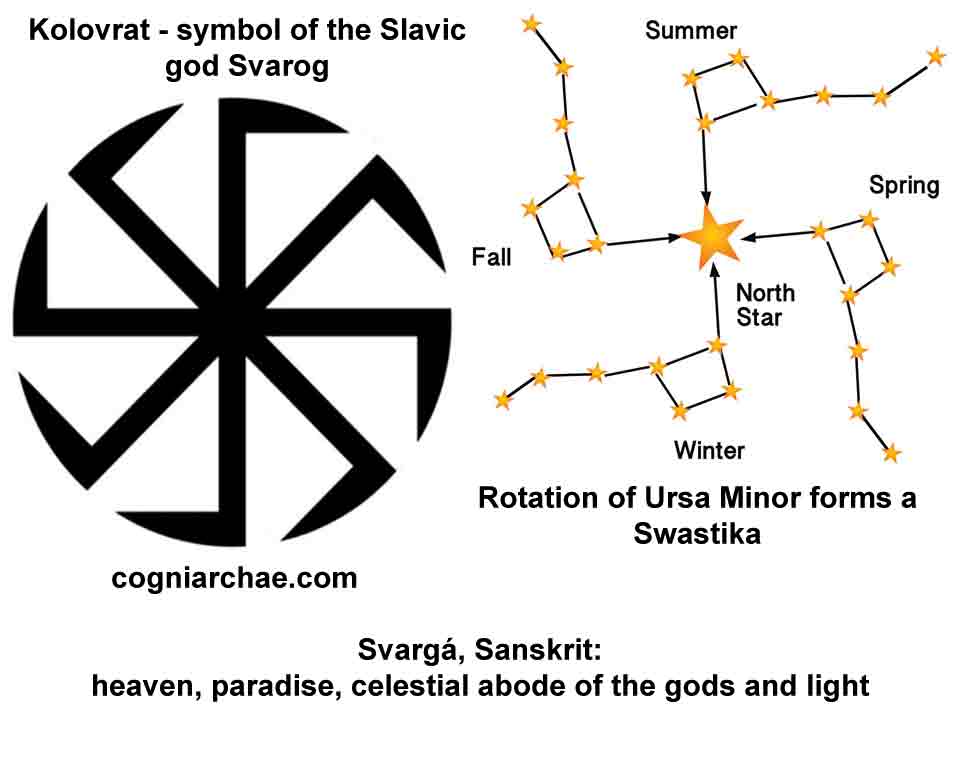

The word “mummer,” though derived from the Greek word for “mask,” is the likely origin of the English word “mum”; to “keep mum” means “to act like a mummer, a mime”—though the word “mime” comes from the Greek mimesis, “imitation; art”, which is related to the Sanskrit maya, the magical or dramatic power by which the Absolute manifests Itself as the universe. The universe, like a mask, both veils and reveals the mystery of the Absolute Reality.

Winter has been a critical period for traditional societies in Europe since times immemorial. People, of course, were aware that the turn of the seasons would eventually bring back spring, sun and food. They knew that the slow, imperceptible change would start when the days are short and cold, and the nights are long and bleak. Despite this, they would crave some reassurance that spring would indeed return, the snow would melt and the plants would thrive again.

Many historians and anthropologists think that this fear from eternal winter and the anticipation of spring are at the core of old and present-day religions, and of countless rites and rituals practised in the coldest months of the year. Christmas is the best known example: the birth of Jesus is celebrated on the date of an old pagan feast dedicated to the rebirth of the sun. The day is close to the actual date of the winter solstice, which marks the longest night in the year.

Bulgarians were not an exception. In winter and early spring they would celebrate several feasts with rites designed to ensure that the new cycle of life would start again. The dances of the kukeri, or mummers, are the most spectacular.

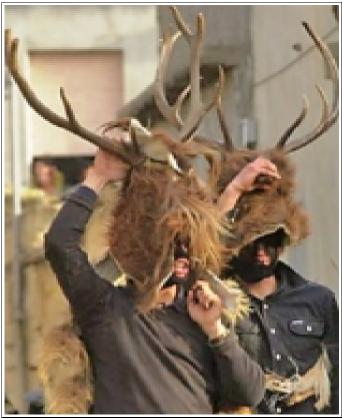

Dressed in animal skins, with faces hidden behind monstrous masks, the kukeri dance in the streets surrounded by the clang of sheep and cowbells hanging on their belts. The cacophony of noises and movements seem chaotic but is far from it. There is a clear concept behind the mummers’ behaviour, a strong hierarchy and even a script.

The mummers organisation and costumes, the dates when they dance and even their names vary across the Bulgarian lands. For example, what is known as kukeri in eastern Bulgaria become babugeri west of Sofia. They can also be called survashkari, mechkari, dervishi, startsi and mechkari.

The group consists of masked unmarried men. They are led by a chief kuker who is usually a married man considered a pillar of the society. On this day, however, his behaviour can be less admonitory. Chasing the women in the streets, he aims to touch their legs with a long, red painted staff. The symbolism is clear: the rite ensures that more babies would be born in the community.

The chief kuker is usually joined by a man dressed as a hag carrying a ragdoll baby. This kuker’s wife is the chief target of the villagers, who would try to abduct her or her baby. When this happens, the chief kuker would go into a mock rage and fight to bring back his wife and child. The couple would also perform a pantomime of sex.

Meanwhile file-and-rank kukeri would dance, go from home to home, dance more and collect food donated by the hosts. Their group can include other characters that openly mock the established social order. A fake priest would chastise people, a mock tax collector would “arrest” them in the streets and demand exorbitant sums of money, a barber would try to shave them with a grotesquely big wooden razor, a fake Gypsy musician would force a man clad as a bear to dance, and so on and so forth.

The chief kuker is not the only person of importance during the day. The rite would be impossible without a “king.” Dressed in the villagers’ idea of royal attire and accompanied by a group of bodyguards or ministers, he has an important task. When the day turns, the king and the whole village would gather for an outdoor feast. The king would not eat by himself, letting his bodyguards feed him. When he is finished, he would ritually plough the ground and sow some grain in it in a ritual that is supposed to provide fertility.

Kukeri costumes are meant to be scary. In different parts of the Bulgarian lands this is achieved through different means. In the west, fur, animal hides and birds’ wings are the norm, while in the east there is a preference for colourful rags and sequins. The mummers in the west would dance immediately after Christmas and around New Year, while their brethren in the east would roam the streets in the days before Lent.

The tradition’s pagan origins are evident. The established theory claims that the Bulgarian kukeri are the descendants of ancient Thracian Dionysian rites. Whatever the kukeri origins, their recent history has changed significantly.

Until the early 20th century, the kukeri dances were vital for rural communities. When the Bulgarian society started to urbanise itself and young people began to emigrate to the cities, the rite started to lose its base, meaning and significance. As it was slowly dying in the villages, nostalgia for the idealised rural life turned mummers into a symbol of “true Bulgarianness” despite the fact that the tradition is hardly unique for Bulgaria and is present in one form or another across Europe – and even as far as Japan. Their rowdy behaviour was tamed, anything resembling sex or mocking the established order was cleansed. The change took place under Communism, a time of rapid urbanisation and modernisation, but also of revived nationalism. By the 1960s, the government was eager to invent a new Bulgarian identity that was both nationalist and Communist. Kukeri, along with folk music, traditional costumes and crafts, were reinvented. Mummers became a modern festival, a spectacle for the eye emptied of its ancient spirit. The obscene antics disappeared and the dances were choreographed and sterilised. Kukeri were reduced to funny figures wearing impressive masks. They were promoted as bringers of health and good fortune to the guileless public, which was itself alienated from its own rural past and traditions.

The trend deepened after the collapse of Communism, when emigration from the villages continued, depopulation took over and nationalism rose, combined with consumerism. The two big festivals dedicated to kukeri dances, Surva in Pernik and Kukerlandia in Yambol, are both organised in towns, not in villages where the natural ground of the rite is. Both events feature troupes from all over Bulgaria and even abroad who compete on who can produce the most spectacular show and costumes. This has resulted in the creation of elaborate masks that would be unthinkable just 50 years ago. Participants also change – some mummer troupes include women and children, a grave disregard for the original essence of the rite, which is dedicated to the fertilising power of men. Some troupes have even monetised their experience – you can book them to put up dance for a wedding feast, regardless of the time in the year.

Of course, there are people who try to keep the tradition alive as close to the original – whatever original in folklore is.

Some of the best places to see kukeri and experience their magic are the villages around Pernik, Razlog and Yambol.

This article is illustrated with images of the mummers troupe in the village of Mogila, near Yambol (by Dimana Trankova; photography by Anthony Georgieff)

- Mamuthones of Sardinia:

The period during which we can admire them during their almost ancestral ritual is during the Feast of the Fires of Sant’Antonio, between the 16th and 17th of January, and then in the midst of the Carnival period, on Carnival Sunday and Shrove Tuesday. Their presence is associated with propitiatory rites for the fertility of livestock and good luck for the year to come; it is a ritual full of symbols and history that goes way back. They say it’s like the battle of good versus evil, winter versus summer vibes.

The Mamuthones embody a kind of ancestral spirit linked to the rural world. Their masks, horns, and bells carry a symbolic meaning that gets lost in history, but they’re thought to be connected to pagan beliefs and propitiatory rituals. They wear traditional leather clothing and a heavy wooden mask that completely covers their faces, adorned with goat or deer horns. They haul around these massive copper bells called “sa carriga” on their backs, weighing like 30 kg, jangling with every step they take, setting up this cool, mysterious vibe.

On the other hand, the Issohadores rock linen shirts, red jackets, white pants, and a female shawl. They sling brass and bronze bells over their shoulders, and some even sport a white mask.

The parade is like an actual ceremony, almost like a procession. The first group moves super slowly, bent under the weight on their backs, while the others keep the rhythm, moving more agilely. Suddenly, they’ll toss their ropes into the crowd to catch someone – to get free, you have to offer them a drink.

- Comparing Symbols of Sardinian Carnivale & Bulgarian Kukeri Festivals of Old Europe Through Common Neolithic Rituals and Bronze Age Mythology by Judith Mann

The intent of this research paper is to trace the antiquity and significance of the rudiments of traditional masquerades still practiced in Sardinia, Bulgaria and other Balkan or Alpine countries through matrilineal ritual symbols from Neolithic Old Europe interlaced with Dionysian Bronze Age rituals based upon Thracian myths.

Additionally, this research is to query accepted beliefs that Carnival origins only began with medieval Christmas, Lenten and Easter holidays, or are merely processions reflecting current popular culture.

In this paper, the symbols of suppressed spiritual consciousness embedded mnemonically in the masks and gear of all-male Bulgarian Kukeri Festivals and Sardinian Carnivales participants, are presented as evolving from Neolithic times in Old Europe, then extending to Sardinia with migrations, and later,

through extensive obsidian trade routes, myths and rituals carried between Sardinia-Corsica, Old Europe and the Mediterranean-at-large.

The Ötzi DNA Connection of Old Europe to Sardinia

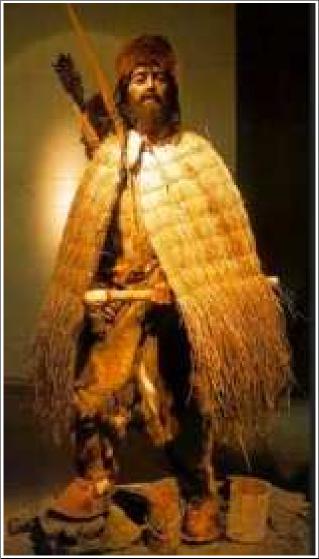

In September 1991, a natural, well-preserved mummy of a 45- year-old hunter was discovered in the Ötztal Alps on the border between Austria and Italy. He had died between 3239-3107 BCE, a time period categorized as Late Neolithic, notable in Europe for Great Mother-goddess-oriented, hunter-gatherer cultures on the cusp of agriculture. Deemed ‘Ötzi the Iceman’, his is the oldest human sample to undergo high-throughput DNA sequencing of an entire genome.

Austrian forensic scientist Walther Parson reported in 2013 that 19 men living not far from where Otzi was discovered, had the same Y chromosome mutation as the Iceman, based upon a study of almost 4,000 Austrian blood samples.

“His lineage is very rare in mainland Europe”. Only 1%t or less share the same sequence, but is rather frequent in northern Sardinia and southern Corsica. The Iceman’s ancestry most closely mirrors that of modern-day Sardinians”. said Stanford School of Medicine’s Dr. Peter Underhill. He came to the conclusion assisting Dr. Carlos Bustamante in analyzing the mummy’s Y chromosome.

Just one small variation on the Y chromosome, a rare Y-chromosome mutation known as G-L91, pointed the researchers to Otzi’s Sardinia-Corsica connection. Sardinians and Corsicans have remained so moored to their genetic past, that a 5,300-year-old individual from Old Europe can clearly exhibit affinities with them. A reason might be the distinct isolation of central Sardinia mountain regions far removed from the often invaded coasts.

Extremely high frequency of I2-M26 Y chromosomes in the Sardinian population signal a major founder event, also adding to their outlier position. The detection of identical chromosomes in Volterra, Italy, suggests an ancient founder or trade connection between Tuscany and Sardinia.

Paleolithic-Neolithic Migrations to Sardinia

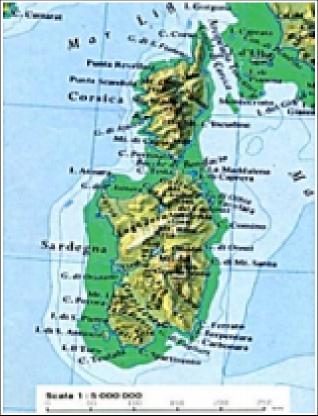

First migrations from Paleolithic Europe to Sardinia-Corsica took place about 14,000-20,000 years ago. when sea levels were lower and access to the single Sardinia-Corsica island was

close to the Tuscan coast, indicated by the submerged green land of Fig. 2. Early drifts brought matrilineal hunter-gather tribes. The oldest bones of Homo sapiens in Sardinia dating back to the Upper Paleolithic period, have been found in the Corbeddu Cave of Oliena, central Sardinia.

A significant portion of Sardinian-Corsican ancestry derives from these peoples, mixed with a subsequent wave of an undiluted Neolithic farmer strain

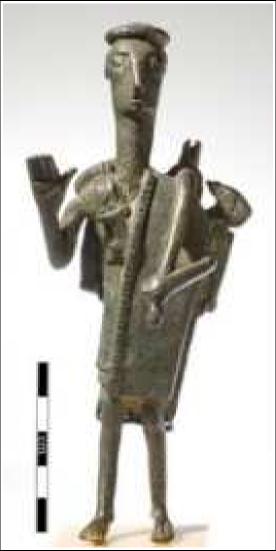

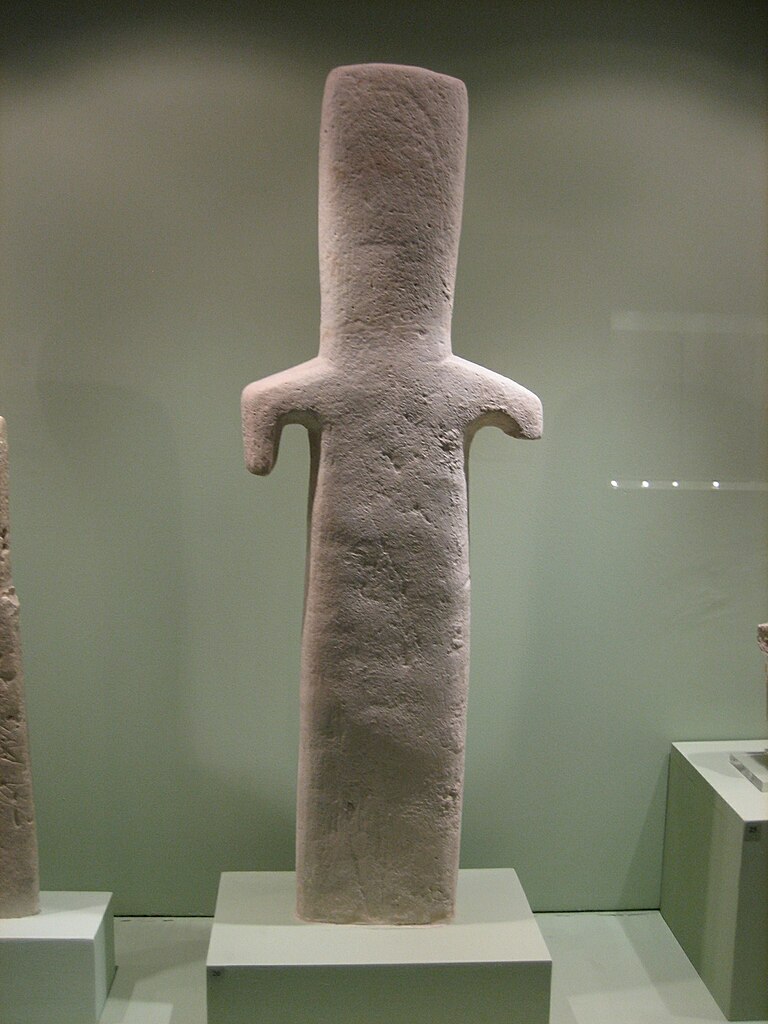

.A 14-inch bronze statue dating from the 9th century BCE, on display the Museum of Cagliari, has been identified as an Early Neolithic farmer by independent researcher, Daniele Cocco.

Rather than a ‘Craftsman’, as labeled by the museum. Cocco bases his conclusion on what now seems obvious, that the figure is carrying, along with a

hoe, a hand plow with a stone head, in use when a man, not an ox, was attached to the yoke.

So this statue precisely captures the 3-7,000 year-old memory of Neolithic origin, the giant leap into agriculture. It is an artistic communication tool inspired by oral history, and preserved intact through the ages. Masked dramas performed today at Sardinian and Bulgarian carnivals, echo the myth of man yoked to the plow.

Obsidian Trade Routes

With the transition into the Neolithic period, obsidian tools from Sardinia became the prototype of exchange. Because of obsidian, Sardinia became one of the most important trade nodes of the entire Mediterranean basin extending to what is now mapped as France, Italy, Crete , Austria, Croatia, and Bulgaria, thus spreading the y Sardo chromosome, 12a2-M26 link.

From Monte Arci, a 3.5 million year-old volcano in western Sardinia, flowed the most ancient deposits of obsidian in the central Mediterranean. Obsidian is a volcanic glass with a black-

glossy appearance, formed when lava rich in silica quickly cools, generating a glassy mass. Because it can be reduced to very sharp shards, obsidian was fashioned into valuable cutting tools, hunting spears, scrapers and arrowheads.

Excavations carried out in 1968, by archaeologists Enrico Atzeni and Gérard Bailloud at a rock shelter called ‘Su Carroppu’ in the Sirri region, revealed obsidian tools from Monte Arci. The remains of ancient meals also found in the shelter, included bones of animals such as deer, wild boar and fish, confirm a 6,000 year-old Neolithic economy based on farming, hunting and fishing in Sardinia and Corsica.

The obsidian trade brought the sea-faring Sardinians into direct contact with the syncretic worship of the high Minoan-Mycenean culture of Crete which reinforced and expanded their own Great Mother rituals, adding those of homage to Dionysus.

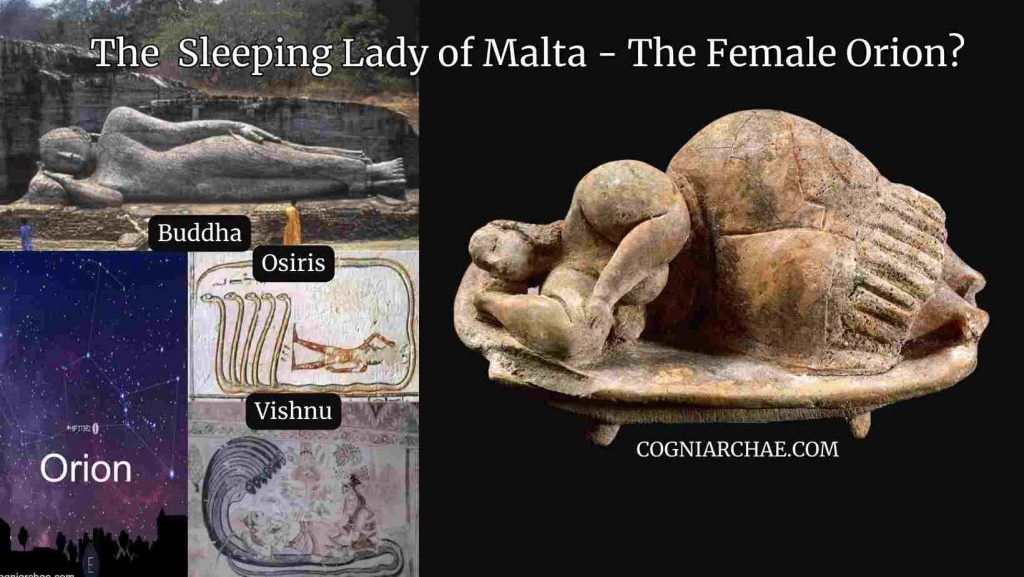

The Great Mother

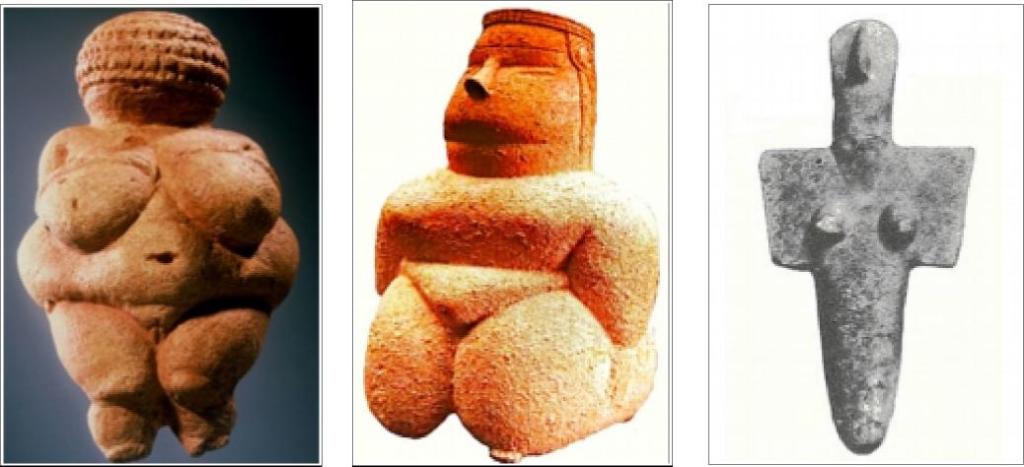

The Great Mother figured prominently in the cultures of Old Europe. Archeologist Marija Gimbutas characterized their unfortified settlements as peaceful, egalitarian, matrilineal. Their worship gave priority to cycles encompassing birth, nurturing, growth, death, and regeneration. (SeeThe goddesses and gods of Old Europe, 6500-3500 B.C )

Focus was on untamed natural forces as well as crop cultivation and animal rearing. As confirmation, extensive caches of goddess figurines have been unearthed in Neolithic settlements along the Danube and in the Balkans. Corresponding stone female figurines shown in Figs. 6 and 7 were discovered at Cuccuru S’Arrius and Senorbi in Sardinia.

ARTEMIS was the Olympian goddess of hunting and wild animals, and the protectress of women and girls.

This page describes her cult in the Greek colonies of Anatolia, the Black Sea, North Africa and Italy. Her cult was often combined with those of indigenous local godddesses, or such foreign deities were simply renamed “Artemis”. The most significant of these was the Ephesian Artemis–an ancient Anatolian mother-goddess who was depicted with a multitude of egg-shaped breasts. Another was the goddess of the Tauric Chersonese on the Black Sea (now Crimea). The cult of these two foreign “Artemises” spread throughout the Greek world. see page

A xoanon (/ˈzoʊ.ənɒn/ ⓘ,[1] Greek: ξόανον; plural: Greek: ξόανα xoana, from the verb Greek: ξέειν, xeein, to carve or scrape [wood][2]) was a wooden cult image of Archaic Greece. Classical Greeks associated such cult objects, whether aniconic or effigy, with the legendary Daedalus. Many such cult images were preserved into historical times, though none are known to have survived to the modern day, except as copies in stone or marble. In the 2nd century CE, Pausanias described numerous xoana in his Description of Greece, notably the image of Hera in her temple at Samos. “The statue of the Samian Hera, as Aethilos [sic][a] says, was a wooden beam at first, but afterwards, when Prokles was ruler, it was humanized in form”.[3] In Pausanias’ travels he never mentions seeing a xoanon of a “mortal man”.

Veneration of the Great Mother found its way from Old Europe to Sardinia during its BonuIghinu and Ozieri periods, from 4000-2800 BCE. Central to the pre-patriarchal worship of the goddess was the miracle of birth and the power to transform death into life through the mysterious cyclical regeneration of nature.

Her arcane initiation rituals were marked by masquerades representing cosmic powers, either benevolent or threatening and myths enacted with masks depicting birds, bulls, mountain goats and deer.n ( See The Chalice and the Blade )

Astrologer, Barry Goddard views these initiations as “essentially inner experiences in which

some new element of Spirit comes into consciousness.”. (shamanicfreestate.blogspot.com)

Deer Masquerades

The oldest known deer rituals may date back 11,000 years, to a time when England was connected to mainland Europe. This premise is validated by a cache of twenty-seven deer masks probably worn by shamans, unearthed at Star Carr, UK in the 1940’s and 2013.

Shamans enter a trance state to communicate with animal spirits, often experienced as a physical transformation into the beast in question. This typically involves wearing a costume that integrates animal references and identifies the shaman with their animal spirit.

Pre- gricultural hunting rituals tended towards such shamanic forms, with deer symbolism linked to cyclical regeneration and antler growth. Northern Europeans in the hunting stage carried an image of the Great Mother as an elk- or wild reindeer-doe, her udders depicted as the source of rain.

Continuing the Mesolithic tradition, villagers in Sinnai, Sardinia, don horned deer masks to act as quarry in an ancient hunt ritual.

As part of the rite, masked Is Canaxus, hunters, push Is Cerbus, deer-men, towards a stake-out for the kill. The goal is to renew divine consent, so as to continue to receive the Great Mother’s gift of prey.

Indo-European Invasions

The dispersion of Indo-Europeans into Old Europe, the Aegean and the rim of the Black Sea, overthrew these civilizations whose most important feature of life was worship of the Great Mother. Three great waves of proto-Indo-European pastoralists from eastern steppes mark the suppression of Great Mother worship by a dominant patrilineal culture. In Old Europe the physical and cultural disruption of the Neolithic societies that acknowledged the Great Cosmic Mother, seems to have started in the fifth millennium BCE, with what Marija Gimbutas termed ‘Wave No. 1, 4300-4200 BCE’, followed by ‘Wave No. 2, 3400-3200 BCE’ and ‘Wave No. 3, 3000-2800 BCE’.

At the core of the invaders’ system was the high valuation on the power that takes, rather than on what gives life. The system was composed of patrilinear, socially stratified, herding units that lived in small villages or seasonal settlements while grazing their animals over vast areas. Its ideology, according to author Riane Eisler, exalted virile, heroic warrior gods of the shining and thunderous sky.

The pastoral invaders increasingly obliterated Great Mother worship because it challenged their authority. Findings indicate that in some invader camps, the majority of the female population was of Old European stock taken in slave raids.

This may have contributed to the remarkable continuity of suppressed Great Mother symbolism appearing in the masked carnivals of historic times.

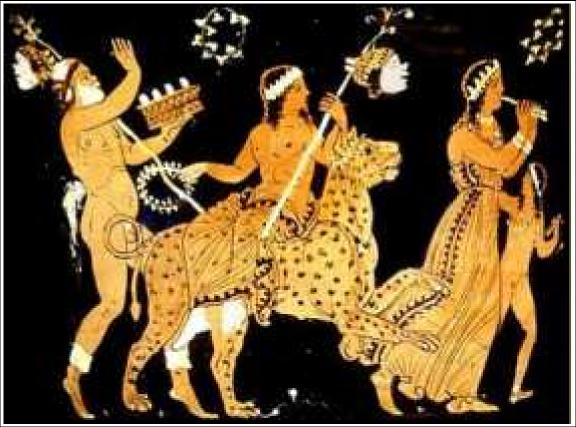

The influence of Mycenaean Crete Early inhabitants of the Balkan peninsula were the Indo-European Thracians, who introduced the cult of Dionysus to the region including Mycenae, through their masked initiations and festivals. The Mycenaeans who went on to conquer Minoan Crete, superimposed the Dionysian rituals onto the existing Great Goddess worship of the Minoans, which appeared to be the most singular and important aspect of daily life.

As mentioned, Late Bronze Age trade voyages to Crete also brought knowledge of Dionysian rituals on return trips, to be blended with the existing Great Mother worship of Sardinia. In his book, The Golden Bough, Sir James Frazer states, “The god, Dionysus is best known as a personification of the vine and as the exhilaration produced by the grape. His ecstatic worship is characterized by wild dances, thrilling music and tipsy excess.”

These attributes are still displayed in the carnivals of remote mountain villages in the Rhodope and Strandhza mountains of Bulgaria and the upland Nuoro Province of Sardinia.

The Thracian festivals that took place at the start of the ancient New Year in early spring, focused on the goddess and her son, Dionysus. Versions of his birth, sacrificial death and resurrection were performed in horn-masked rituals to ensure renewal of the cosmos and society.

Though Dionysus was considered a deity of vegetation, he was often depicted as a bull or a goat, or wearing Taurine horns. Legend has it that he was in bull form when torn to pieces, reenacted in Crete by an actual bull being ritually torn apart and consumed raw. His worshippers may have believed they were eating the flesh and drinking the blood of a god. The killing of a bull or goat came to be regarded as no longer the direct slaying of a god, but seeas a sacrifice offered to him. Hence, Dionysus eating his own flesh and gaining resurrection. see Orion worship – part 1 – Christianity and Orion worship – part 2 – Dyonisian mysteries

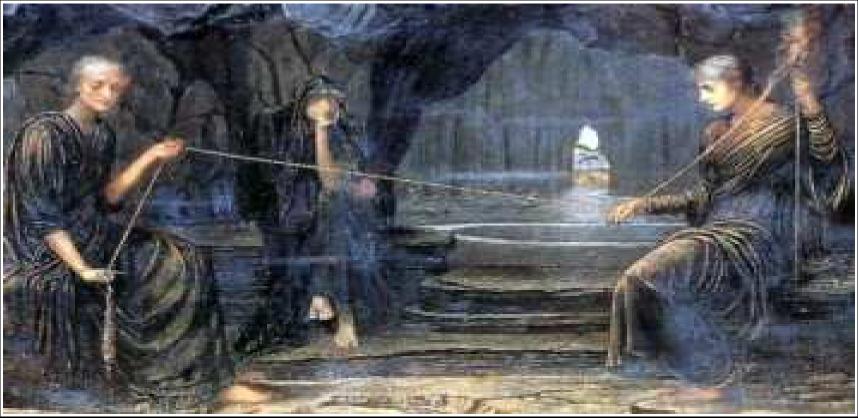

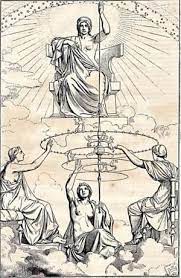

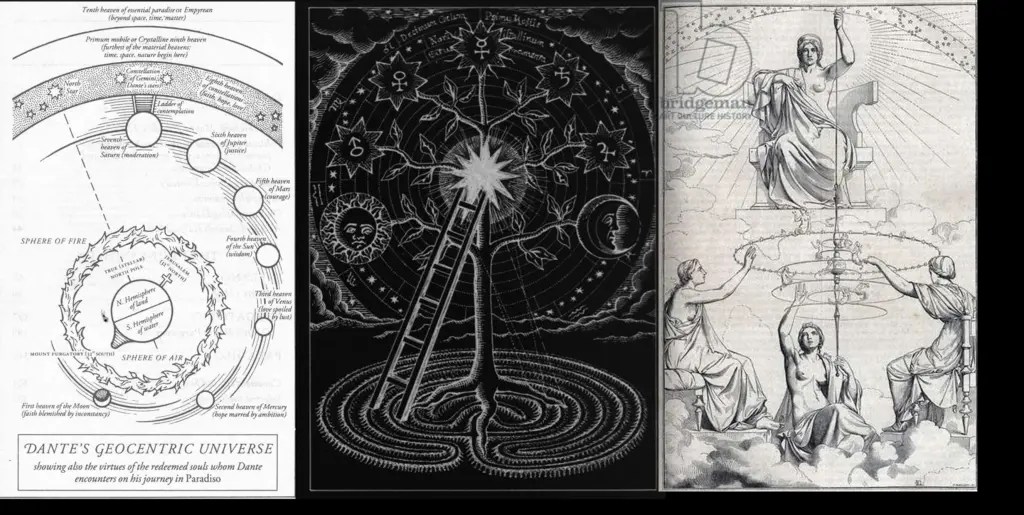

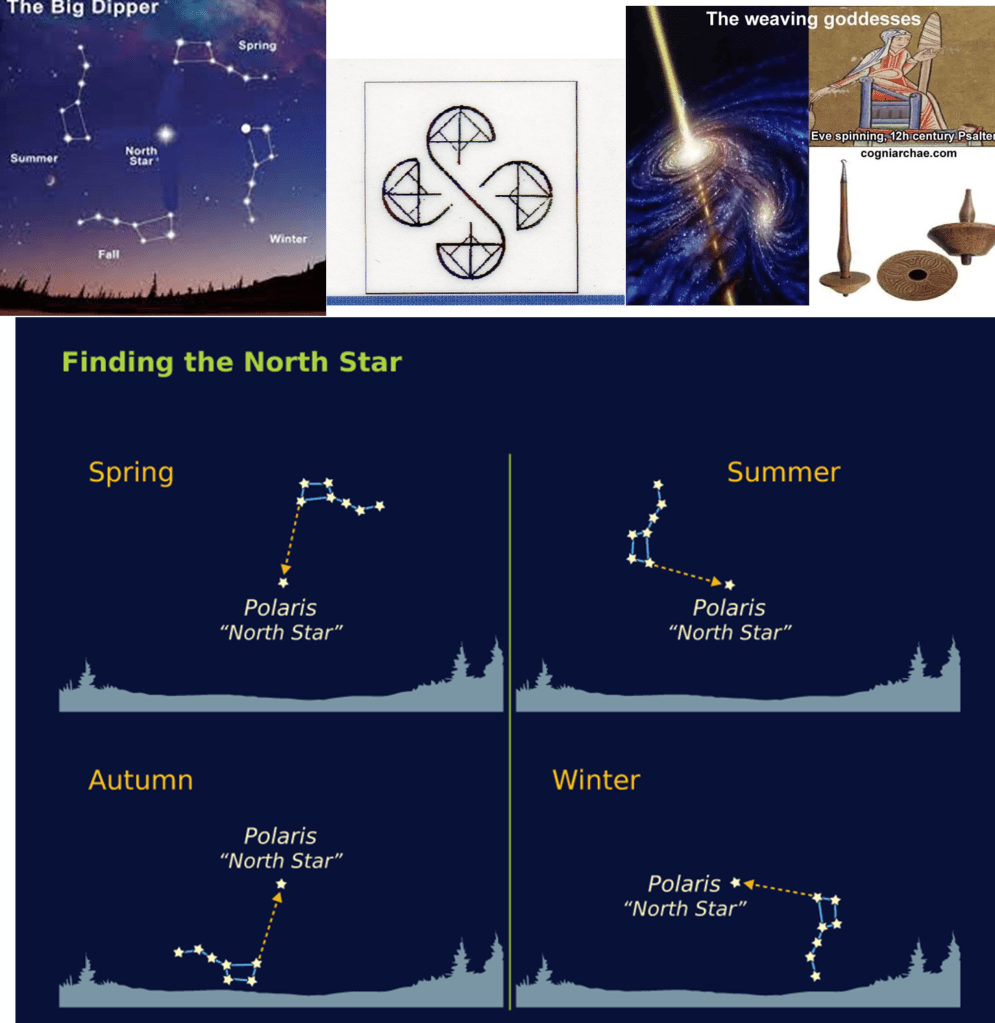

Thread of Life

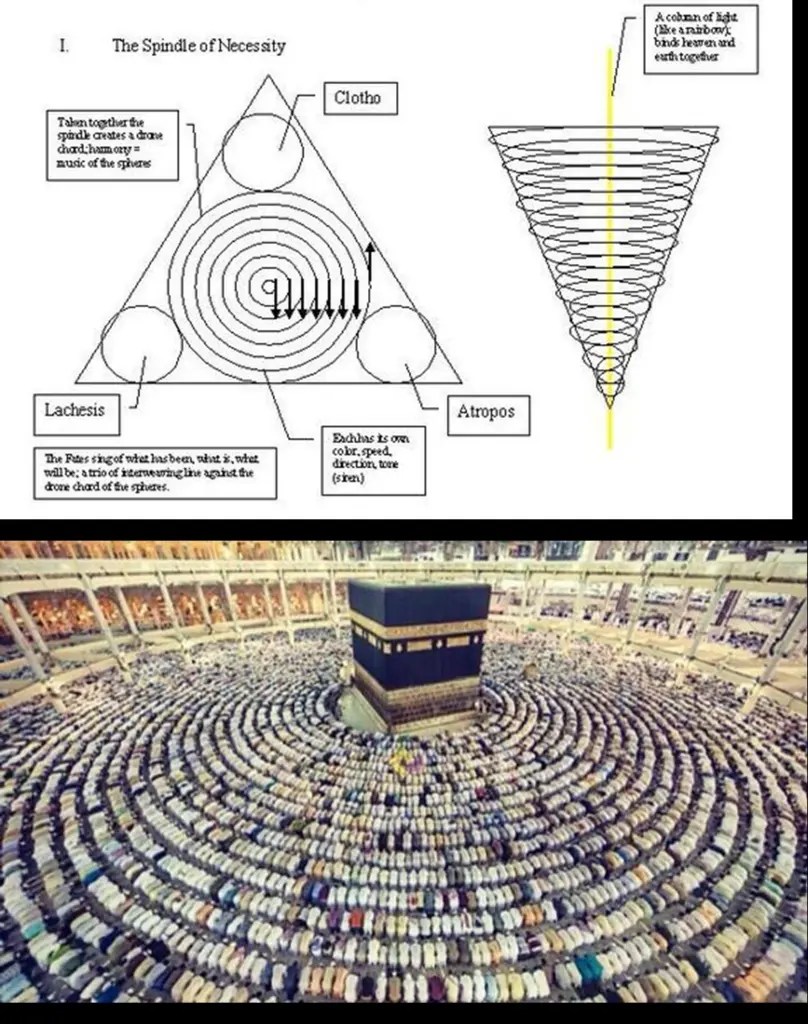

The Moirai were the three goddesses of Bronze Age mythology who personified the inescapable destiny of humans and gods. They assigned to every person his or her share of daily life. The sacred trinity was composed of Clotho who spun the thread of life from her distaff onto her spindle, Lachesis who measured the thread of life allotted to each person with her measuring rod, and Atropos, the cutter of the thread of life. She chose the manner of each person’s death; and when their time came, she cut their life-thread with her loathed shears.

In Neolithic times, the three Fates were considered daughters of the primeval goddess to whom the gods themselves must bow and considered aspects of time:

Lachesis represents the things that were, Clotho the things that are, and Atropos the things that are to be.

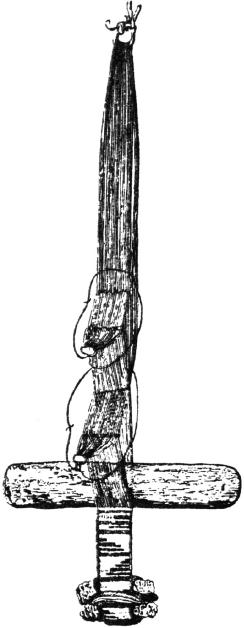

Common to the Sardinian Carnavale and the Bulgarian Kukeri Festival is the crone character, Filonzana, whose face is either painted with soot or wears a mask and dressed in black expressing deep mourning. The crone stays close to the ‘victim’ in the procession; the thread coiled on

her spindle, the symbol of destiny. As birth naturally ordains death, the thread will soon be cut and the scapegoat cursed to prevent guilt from clinging to his killers as they spill his redeeming blood . Moirai or Filonzana embody a sentient power governing the limit of life.

There appears to be an early dynastic Egyptian influence on the Sardinian crone, occurring through a Minoan Cretan connection with Egypt. The little-known ancient Egyptian goddess Meskhenit was defined by Sir Wallis Budge as ‘the goddess of the birth chamber’ and also as a presiding presence at the time of death, an antecedent to Filonzana’s functions.

Laird Scranton observed in his book, The Science of the Dogon, “the passages that Meskhenet oversees relate to a gateway between the non-material and material, one that takes on different nuances of expression depending on whether we consider it in relation to the universe/macro-cosm, the formation of matter/microcosm, or biological reproduction.”

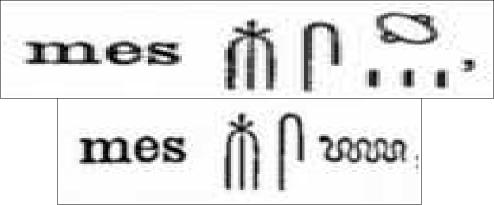

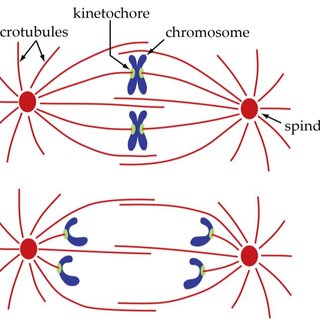

Scranton associates the name of the goddess which rests on the phonetic Mes with glyphs relating to a modern scientific perception of spindles and chromosomes in molecules through the concept of a dipole, a pair of separated electric charges of equal magnitude but of opposite sign or polarity. Certain hieroglyphs from the 30th Dynasty Metternich Stele can thus be interpreted.

Reading the hieroglyphs from left to right, a ‘chromosome’ glyph combined with a curved staff glyph conveys the idea of creative transition, the glyphs depicting the act of giving birth, the act of weaving, and the vision of energy shown as a snake undulating

between nonmaterial and material domains. In that context, Meskhenit oversees not a static life-ending moment, but the energetic gateway of death.

see also The Thread of life: Wisdom for our Times

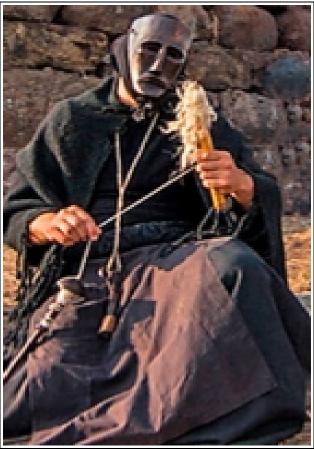

The Kouker

The village of Indje Voivoda, Bulgaria, hosts an early spring festival revolving around a single Kouker who is sacrificed and born anew, akin to Dionysus. The role of Kouker, whose original Greek name has been defined as ‘rod-carrier’, serves the double function of chasing evil spirits and endowing fertility. This ritual has been performed continuously from ancient Thracian times to the present to restore order to an otherwise chaotic world.

The Kouker’s face is blackened with rye straw soot mixed with oil as a sign of transitioning from one world into another, rather than wearing a formal mask. His costume, created from seven sheep or goat hides, is deconstructed at the end of the festival to be buried in seven different parts of the farmland outside the village. Bells suspended from his waist and horns atop his hood refer to the sacrificial bulls of ancient cults.

He carries a phallic pole during three tours of the village, striking both ground and female spectators with the assumption they will conceive faster after being hit. Only the crone can resurrect him after his sudden death during a staged fight, reenacting the sacred mother-son mystery initiation. Everything in the ritual episodes speaks to the cyclical destruction and renewal of the universe.

Add the observation of author Riane Eisler, that the Paleolithic association of sex with communal sharing and benefiting from the bounty is made possible by the rebirth of nature each year in the spring. In most other Bulgarian village celebrations, multiple Koukers evolved from the single Kouker character and appear as a group in ornate masks and garb.

It is the story of twin brothers, abandoned in the woods in infancy. Valentine is brought up as a knight at the court of Pepin, while Orson grows up in a bear’s den to be a wild man of the woods, until he is overcome and tamed by Valentine, whose servant and comrade he becomes. In some versions, the pair discover their true history with the help of a magical brazen head. The two eventually rescue their mother Bellisant, sister of Pepin and wife of the emperor of Greece, by whom she had been unjustly repudiated, from the power of a giant named Ferragus.

See also the Mythology, Legends and Fairy Tales of Friesland

Note :In Friesland you have Sunneklaas or Sunterklaas is a variant of the Sinterklaas festival in which elements of pre-Christian traditions are mixed with traditions and stories about Saint Nicholas. This folk festival, which also shows similarities with the Krampus tradition, is celebrated annually on or around 5 December for two consecutive days on the Dutch Wadden Island of Ameland.[a] It is the most important festival of the year there and the roughest of all the variants of Sinterklaas on the Wadden Islands.

Sunneklaas is an old tradition that is part of the Ameland identity. It is a festival of, for and by Ameland residents that is celebrated in its most original form in Hollum and Ballum. Especially in these western villages on the island it is shrouded in secrecy and outsiders are kept out.[b] Due to media exaggeration of the little information that comes out, Sunneklaas has an image of a misogynistic horror festival where no laws apply.

Significance of Mamathune Masks & Costumes

Masquerades focused on the characters of the Kouker in Bulgaria and the Mamathunes in Sardinia may be among the most ancient, arriving barely altered from the Paleolithic times of Great Mother worship.

The name Mamathune. translates as ‘the men who call for rain’ , a shamanic under-taking for survival in a parched land. Their sheepskin costumes evoke a prehistoric man-animal connection. A female kerchief knotted over the rugged contours of a carved wooden mask or a blackened face, signals the androgynous nature of the Mamathune. This is worn in

stark contrast to the rough clothing and masculine boots of the participant. Approximately one hundred pounds of large bronze cow bells are carried on the back, secured by tight leather straps. Smaller bells are secured on the front, purportedly to ward off evil spirits. Similarly, Kukeri wear both sets of bells, straps, skins and grotesque masks or blackened faces, though generally, not the kerchief. Other research ascribes a satanic origin to the black Mamuthone mask, and the entire procession is presumed to be a kind of ritualistic exorcism .

Darkened Faces

Though the carnival custom of darkening the skin with soot or wearing dark carved wooden masks is attributed to the demonic or to animal nature and to be ritually exorcised, it actually might refer to a deep collective urge to display the genetic memory of chronologically distant European ancestors who were dark-skinned before the advent of the Ice Age.

According to evolutionary biologist Eske Willerslev of the Natural History Museum of Denmark, ancient DNA taken from the 36,000 year-old fossilized skeleton of a short, dark-skinned, dark-eyed young man, contains all the genetic components found in contemporary Europeans. He is known as the ‘Kostenki Man’ from the Don River, Russia.

The data, published online in the November 2014 issue of Science Magazine33, suggests that today’s Caucasian Europeans are descendants of an interconnected population of dark hunter gatherers that had spread throughout Europe, Asia and the Middle East 36,000 years ago, long after leaving Africa.

A branch of this founder population called basal Eurasians, spread north and west into Europe and central Asia. These people interbred at the edges of their separate populations, keeping the entire cmplex network interconnected and so giving the ancient Kostenki man genes from three different groups, indigenous hunter-gatherers within Europe, people from the Middle East, and northwest Asians from the Great Steppe of eastern Europe and central Asia along the Middle Don River in Russia presents a different view: This dark-skinned young man with DNA from all three of those migratory groups was already ‘pure European‘.

Procession Movements

The first jump that a Mamathune or a Kouker takes is the most memorable, for it is the archetypal jump from the womb of the Great Mother, announced by the haunting sound of bronze cowbells.

The sound becomes even more impressive multiplied by twelve Mamuthones jumping simultaneously. On signal, they quickly jump three times in place, producing three sharp, powerful ringing sounds from their entire outfits. The claps reverberate through narrow cobble streets.

The group of twelve, who symbolize the number of months in a year, parade slowly in two parallel lines under the weight of the cowbells. Their every movement plays a significant part in the ritual. As they press forward, the Mamuthones acting as one

organism, swing their shoulders and twist their bodies, first to the right and then to the left. These gestures in two

beats accompanied by deeply resounding bells, is executed

in perfect synchrony despite the weight of their outfits, the mask’s obstruction of vision and tight straps limiting their

freedom of movement.

The motions of this sacred procession suggest an ancestral memory of a miracle of twisting descent culminating in the birth of humankind. The profoundly dignified ceremony linked to the eternal cycle of birth and re-birth, honors the androgynous Great Mother.

Return of Spring Sacrifice

The ancient custom of sacrificing divine kings is played out in both Bulgarian and Sardinian festivals in the Dionysian mode by distributing virtual fragments of their mutilated bodies over village fields, thus ensuring the return of a fertile spring. The tradition, which associates the sacrifice of the king or his children with a great scarcity of crops, points to the belief that the king is responsible for the weather and harvests. The spilled blood evokes rainfall for the parched earth, essential for collective survival. According to Frazer, when gods are killed, they take on the role of scapegoat, sweeping away disease, death, and sin from the community, and are eaten symbolically in order to be assimilated.

In the carnival enacted in Samugheo, Sardinia, a related character called S’urtzu-Dioniso, symbolizes the god to be sacrificed. He appears as a goat, which according to legend, is how Dionysus often appeared. Under the goat skin is a bladder filled with blood and water. When he is hit and falls, the bladder breaks and red blood soaks the ground. After this sacrifice, new life emerges.

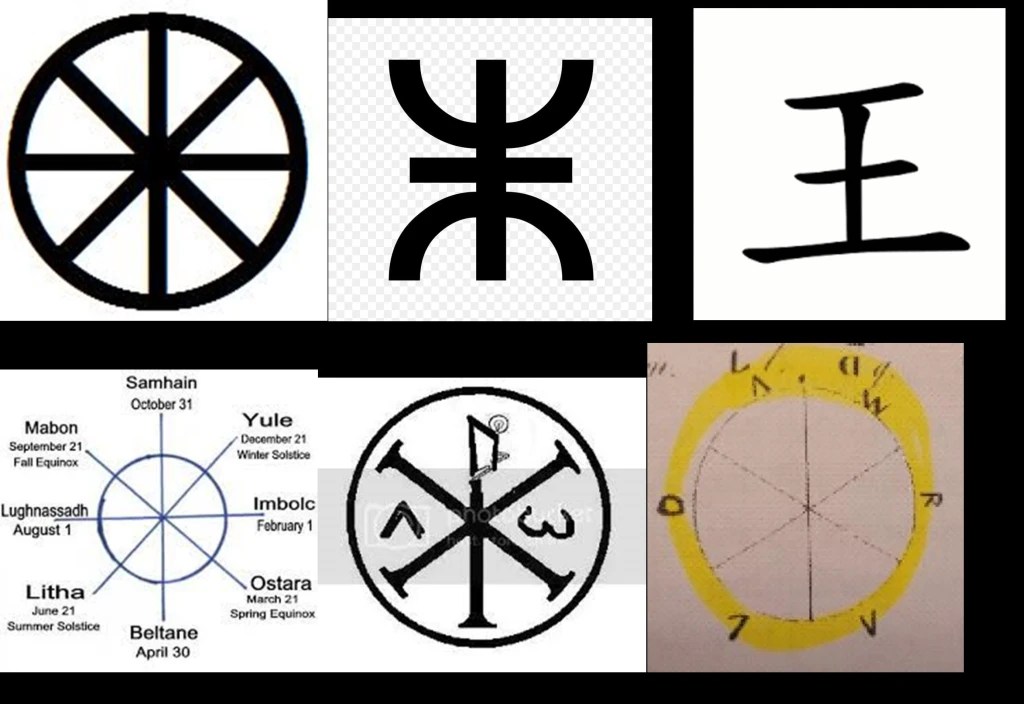

Kukerovden, which translates as ‘Day of the Kukers’, is a Bulgarian mystery play within the festival, in which each player bears a strong symbolic connection to an archetypal aspect of nature. The Neolithic ritual is designed to bind heaven and earth together by telling a human story that echoes the greater, universal drama.

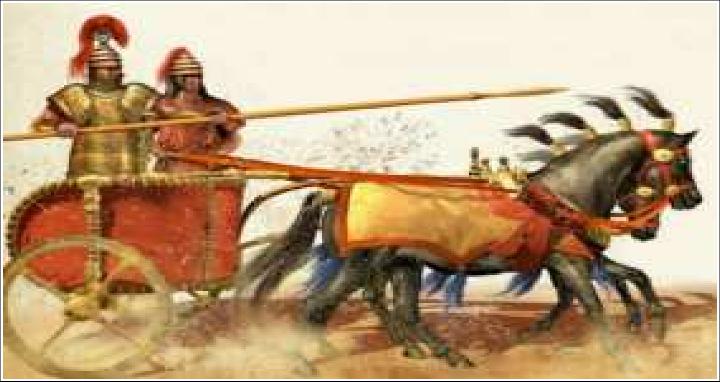

The wine-fueled Kukerovden ritual includes a tsar or king and a human couple along with a team of attendant kukeri. In an act of bawdy pantomime, the groom impregnates his bride as the kukeri charge, dance and interact with the crowd, jabbing, thrusting, and chasing girls with their long, red poles. Two kukeri are then yoked to a wooden plow, goaded by the tsar as they ritually till three concentric rings. The tsar scatters grain seeds symbolizing the sowing of fields.

The heated climax occurs when the tsar is struck down with the spindle of destiny. Raising his body announces the arrival of spring. By now the bride, a male disguised with kerchief and comically bulging dress is ready to give birth. When the child pops out, usually represented by an androgynous rag doll, the ceremony is complete.

The ritual seems to have originated as an initiation for young Kukeri, historically, boys and young bachelors. Through phallic thrusting and sowing movements. older men would convey the ways of the world and their community. Maimon is the name by which Dionysus is invoked in Sardinia. In Orotell, Maimones mime cultivation by dragging a plow behind them. The deep, indissoluble bond is indicated by ropes that bind the farmers to the yoke. It is no coincidence that Dionysus was especially adored by farmers who considered him the inventor of the plow and the one who had taught men how to lure oxen to ease their labour.

The Koukeri tradition recreates the connection between Nature and Man: earth – woman; ploughing the soil – taking the woman; sowing – inseminating; grain – semen; passing of winter – killing of the Tsar; coming of spring – the Tsar’s resurrection. The Koukeri’s moves bear the signs of sacral code: The stabbings with the red-painted swords represent the phallic copulation moves; the hopping and jumping are to make the wheat grow tall; the body swaying – to make the wheat sway with heavy grain; the rolling on the ground – for Man to take from Earth’s strength; the bells noise – to scare and chase away the evil spirits.

The Koukeri custom was part of the game cycle that prepared the young men for their future roles of husbands and land workers. It was an important rite-of-passage, which gave them the opportunity to learn about and experience life after marriage. A lad, who had not participated in the Koleda, Sourva and Koukeri games, would be considered a “second rate” marriage candidate, and would be put in the same group with the non-healthy and widowed men. He could only marry a “second rate’ woman – non-healthy, widowed, or one left by her husband.

The main actors of the Koukeri group are: a Tsar (king), a newly wedded couple or an elderly couple, koukeri. They have a chariot or a cart, in which they drive the Tsar around; a plough, with which they ritually till the soil; a wooden pot, full of grain, which the Tsar sows; wooden swords and a club, perceived as phallic symbols; a doll. Despite the regional variances, in the past, the ritual comprised the following sequence of actions: The Koukeri, only young single men, led by the Tsar, a man of respectable age and social standing – prosperous, with a family and children, gathered in the centre of the village, from where, with the musicians in front, they would go to all houses, offering blessings for health, fertility and prosperity. The Bride tries to sweep and clean up the front yard, but does it so clumsily that only causes disorder. The Hosts give the Koukeri food, wine and/ or money, and thank them cordially for the blessings. In turn, the Bride kisses the Host’s hand. After the house rounds have been completed, the Koukeri group, followed by villagers, return to the village square, where they perform their ancient ritual. First, they engage in a battle with the evil spirits by running around, waving arms and swords wildly, and making noise with their bells, thus chasing the evil forces away. The Groom / Old Man use the scuffle to “make love to and inseminate” the Bride / Old Woman. The Koukeri return from the battle and give their Tsar three pieces of bread. Then three circles of ritual ploughing take place. The Tsar walks behind the plough and sows grain, followed by the main group, who are jumping and waving their swords in the air. Upon completion of the tilling, the Tsar blesses the congregation for good health and prosperity, and is then killed by a Kouker. All Koukeri gather above him and resurrect him. The Bride/ Old Woman gives birth to a child, and the Koukeri celebrate with hopping and dancing. During the enactment of the custom, the Koukeri exchange jokes with the spectators. At the end, the Koukeri gather for a dinner with the food and wine, given to them by the villagers. It’s a joyous and elevating event.

In our days, the Koukeri Day is just a festive reminder of times gone by, a merry holiday, whose main importance is to gather people for a joyful celebration of life.

The Sardinian version of carnival is called Carrasecare,’meat carried in a cart to be dismembered’. But the term care does not mean meat for butchery, which is always called petta or petza. The term suggests human meat, revealing the arcane function of traditional Sardinia carnivals. Maskers continue to play out the roles, though with different intentions. They are sad events that require a victim or a stand-in effigy to be torn apart, incarnating the deity who had been eaten by Titans, then resurrected by his mother.

The cart also serves as the platform for enacting the consummation of the divine union between the Neolithic Great Mother and her consort-son in Bulgaria. They reappear in Minoan myth as either Demeter or Semele, depending upon the version, as the stand-in for the Great Mother and her consort- son, Dionysus in bull form, representing male virility.

Ensured through these mini-dramas is the fertility of the fields, fruit trees and grape vines, the source of the wine that keeps the excitement of the festivals alive. The magic of these long-repeated rituals seem to be regarded as guarantee for a rich harvest, health and fertility for humans and their domesticated animals with chaos subdued and evil spirits chased away.

Read also:Cernunno, Odin, Dionysus and other deities of the ‘Winter Sun

and : Divinity of the Underworld, the Afterlife and the Mysteries

Note:The Mystical Origins of the Kukeri: Bulgaria’s Strangest Folk Festival

Freemasonry describes itself as: “A beautiful system of morality, veiled in allegory, illustrated by signs and symbols.” Much the same could be claimed for Bulgaria’s kukeri ritual. In the masonic lore, Hiram Abiff was the chief architect of King Solomon’s Temple. He designed the building according to principles of sacred geometry, which he taught to his apprentices. Three of those apprentices were impatient though, and demanded their master revealed to them all of the secrets at once. One after another they set upon him with their working tools, and on the third strike the master architect was killed. In the ritual reconstruction of this fable, the candidate plays the role of Hiram Abiff; and on being raised from the symbolic grave he is reborn as a Master Mason.

It’s certainly tempting to draw parallels between the rituals of the kukers and the freemasons. Further west, links between mummery and freemasonry have been hypothesised… there’s even a theory that all mummers are freemasons, whether they know it or not. In this case though drawing any kind of connection between the two is problematic.

For a long time the only freemasons in Bulgaria were Turks. The Ottomans adopted the craft from the French and British, and particularly during the Crimean War there was a huge transfer of traditions by way of military lodges.

Bulgaria was a part of the Ottoman Empire at the time… but the Bulgarians themselves were usually forbidden from joining Ottoman lodges.

During those dark centuries of occupation the Bulgarians were treated very poorly. They were second-class citizens in their own country, living under an Islamic caliphate whose Sharia law was enforced by brutal Ottoman militias. Their population was spread across largely agricultural settlements the length of the country, with poorly-developed systems for communication between them; conditions that allowed for almost endless regional interpretations of the kukeri ritual.

It’s curious to think that these two ritual practices once existed side by side; freemasonry as a system of allegorical plays for the ruling class, while the equally esoteric Kuker Games were handed down through the native population. The kukeri ritual has even shown signs of evolving over the years, adopting some Turkish elements along the way; there’s the ‘Byulyukbashiya’ for a start, and in certain regional traditions from the south of Bulgaria the part of the priest is replaced with an imam. But given the spread of these communities, the distance between them, it seems impossible that such influence could have happened on anything but a local scale.

Whatever the Kuker Games have in common with freemasonry then, comes not from a transfer of tradition but rather as the result of sharing a similar source; with both of these ritualistic systems displaying the archetypal hallmarks of the solar deity myth, that originated in the empires of antiquity.

Conclusion

Despite numerous invasions, suppression and co-opting of their cultures, the indigenous rural populations of Sardinia and Bulgaria manage to retain, almost intact, their root myths and rituals, legacies to guide future generations. How ancient symbols and legends are interpreted still underlies the shaping of both our present and our future.

This paper reflects author Octavio Paz’s statement, “The essential attribute of Carnival is a time apart from ordinary life, a wild time of exuberant, uncontrolled, licentious behavior in which chaos reigns and order seems to disappear”.

However, what must be taken into account is that these rituals establish their own order through collective participation, so that social relationships and values are reinforced during the remainder of the year. The reinforced values attuned to natural cycles, may prove to be invaluable in these uncertain times.

– Saint George: Great Martyr and Triumphant

Saint George (Greek: Γεώργιος, Geṓrgios; Latin: Georgius; d. 23 April 303 was a Roman soldier of Greek origin and a member of the Praetorian Guard for Roman emperor Diocletian, who was sentenced to death for refusing to recant his Christian faith. He became one of the most venerated saints and megalo-martyrs in Christianity, and was especially venerated by the Crusaders. Orthodox Christians commemorate his feast day on April 23rd.

Saint George’s Day, also known as the Feast of Saint George, is the feast day of Saint George as celebrated by various Christian Churches and by the several nations, kingdoms, countries, and cities of which Saint George is the patron saint including England, and regions of Portugal and Spain (Catalonia and Aragon).

Saint George’s Day is normally celebrated on 23 April. However, Church of England rules denote that no saints’ day should be celebrated between Palm Sunday and the Sunday after Easter Day so if 23 April falls in that period the celebrations are transferred to after it. 23 April is the traditionally accepted date of the saint’s death in the Diocletianic Persecution of AD 303.[1]

The fame of St. George increased throughout Europe in 1265 by publication of the Legenda Aurea (The Golden Legend) by James of Voragine, a collection of stories which included that of George and the Dragon. Actual origin of the legend of George and the Dragon is unknown. It may have been begun by the Crusaders when they returned home but was not recorded until the sixth century. St. George was a prominent figure in the secular miracle plays performed in the springs of medieval times. Some hold the story to be a christianized version of the Greek legend of Perseus said to have rescued a princess near the Lydda where St. George’s tomb is located.

A poll published last week by the IPPR, a Left-leaning think tank, suggests that seven out of 10 people living in England want Saint George’s Day to be a public holiday. Well, on Ethiopia’s Saint George’s Day they surely have a public holiday, as it falls on the same day as Labor Day.

Even a Google Doodle marked once Saint George’s Day with an image of Ethiopia’s Patron Saint slaying a dragon. Read more here

St. George and the Miracle of Mons – Belgium

- World War I Miracle? The Angels of Mons

Surrounded by the Germans who outnumbered them five to one, 4,000 Commonwealth soldiers fought their way through and were saved from certain death. They had barely returned to camp when a rumour began: angels from heaven had led the way.

Doomed to death

While the Battle of Mons raged and they had lost count of the number of British soldiers who had been killed by enemy fire, the 8th brigade was fighting tooth and nail to defend Mons. On the evening of 23 August, as night was falling, the situation was serious. The 21,000 Germans involved in the battle had made it to Mons from the East. They were occupying the city and threatening the British rear. On the right, the situation was just as dire, the Commonwealth soldiers had to tackle the 7th Bremen Regiment, which was holding Spiennes. Despite all this, the 8th Brigade miraculously made their way out. They managed to find their way through the darkness to get to their camp. The story might have been left there, if a rumour hadn’t started to spread among the soldiers. Some claimed to have seen angels in the form of archers. They supposedly stopped the Germans in their tracks so that the British could retreat. Fiction or reality? Of course it’s hard to say. The Great War gave rise to plenty of legends. On some parts of the front line, soldiers are said to have been helped by celestial figures to stay alive.

A legend that has gone down in history

The church and then the British government used this event to motivate soldiers to continue to fight. Shortly afterwards, the fantasy writer Arthur Machen published an article in the London Evening News about the event. He told the story of a British soldier who was helped by archers to escape from the claws of the German army. He alluded to Saint George, the patron saint of soldiers and a legendary character for Mons.

Although he quickly admitted that he had made up the whole story, there was no longer any doubt. The legend took on different forms. The angels were presented in different ways, either as a cloud of light or a winged horseman. The famous legend of Mons is still widely written about today, 100 after years after the war began.World War I Miracle? The Angels of Mons read more and look also “The Great and Holy War”

The 800-year-old Doudou of Mons Read more here

- St George: The Art of Dragon Taming:

Paul Broadhurst in “the Green Man and the Dragon”told about the art of Taming the dragon in Britain:

One of the best-selling books of all time was The Golden Legend, written by the Bishop of Genoa Jacobus de Voragine. In it he provided the medieval world with a definitive account of the lives of the saints, which everyone at the time believed to be historical facts gleaned by his scholarship from ancient records. In reality, like so many others that were to follow down the centuries, it was a motley mix of fact and, where there were no facts, a liberal dose of fiction. There was also an agenda.But it was a formula that gripped the attention of its readers, who preferred to believe in the fabulous and miraculous exploits of their heroes, just as in Celtic times when people loved to hear of the wondrous world of giants, gods and the Land of Faery. The saints were all these, and more, for they did the work of the one true God.

Printed in English in 1230 it contained a detail of St George’s career that had strangely hitherto gone unmentioned in the voluminous annals of the saint’s life. Almost a thousand years after his supposed death George was to become famous all over the world for what was his most fabulous exploit of all—the slaying of a dragon.

Jacobus’ story is a classic mix of fairytale heroic deeds and propaganda aimed at the conversion of previously pagan believers to the true faith. In it St George came upon the city of Silene in Libya where a terrible dragon ‘envenomed all the country’.

When the inhabitants set out to rid the land of it they were overcome by its foul breath and fled in terror. To keep the monster satisfied they fed it two sheep every day; if they failed to do this then it devoured a man instead. A local law was proclaimed that children should be selected by lots, and whoever the lot fell upon, whether rich or poor, they were to be sacrificed to the beast. But one day the lot fell upon the King’s daughter. He offered the townsfolk gold and silver instead but they would not be moved; it was the King’s daughter or they would burn down the palace. Lamenting that he would never see her married he begged for eight days respite, and then, when again approached by the desperate inhabitants who reminded him that the ‘city perisheth’, dressed her in the finest wedding gown and, blessing her, took her to the dragon’s lair.

As it happend, this was the very moment that St George was passing by, and no doubt struck by the sight of an attractive woman dressed for a wedding and hanging around in a swamp, he naturally enquired as to her well-being.

She replied that he should go on his way, lest he perish too. But the valiant hero, on learning of the imminent arrival of the dragon, would have none of it; `Fair daughter, doubt ye no thing hereof for I shall help thee in the name of Jesus Christ.‘

At that very moment the dragon appeared and charged towards them. St George made the sign of the cross, struck it with his spear and threw it to the ground. Then he said to the maiden, ‘Deliver to me your girdle and bind it about the neck of the dragon and be not afeard‘.

The dragon, up until that moment a terrible beast that would devour anything, instantly became as meek as a pet. They led him to the city, where the people were aghast and began to flee. But George said that if they would believe in God and Jesus Christ and be baptised into the Christian religion he would slay the dragon and save them all. There was no argument. The King was baptised immediately, the dragon’s head was cut off, and all 15,000 men as well as all the women and children became Christian.

The King built a church to Our Lady and St George, where the waters of a magic fountain healed the sick. He offered George great wealth, but the saint asked for it to be given to the poor. And so they all (except George who was evidently later to be horribly tortured by Diocletian) lived happily ever after…

The elements of the story are the same as many folk-tales which people would have been familiar with at the time, and this applies to the formula as well: damsel in distress is rescued by brave hero who saves the land from devastation.. It is the very stuff of legend as recounted endlessly throughout history. Yet certain parts indicate something else is going on `behind the scenes’, which may help to enlighten us about its real meaning.

To begin with, it is strange that the townsfolk choose to give their children to the dragon when sheep seemed to keep his hunger at bay. Or surely they wo have preferred to send one of their more elderly residents to the dragon ’s lair?

This looks as though it refers to some form of ritual sacrifice, where the vitality of the young is an essential feature (the story of Abraham sacrificing his son Isaac on the rock at Jerusalem is another example of a reference to this primitive method of appeasing the gods).

Then we have the King’s daughter all dressed up in her wedding finery. This too is reminiscent of ancient ritual. But who is she to be married to?

Presumably, as she is about to go into the dragon’s cave, she is about to enter the underworld with its monstrous inhabitants. It is very much as tho she represents the archetypal maiden of the Earth, an innocent young woman about to confront the hellish denizens of the hidden realms. The word Hell though, before it came to have Christian associations of torture and retribution merely meant transformation. Read more here

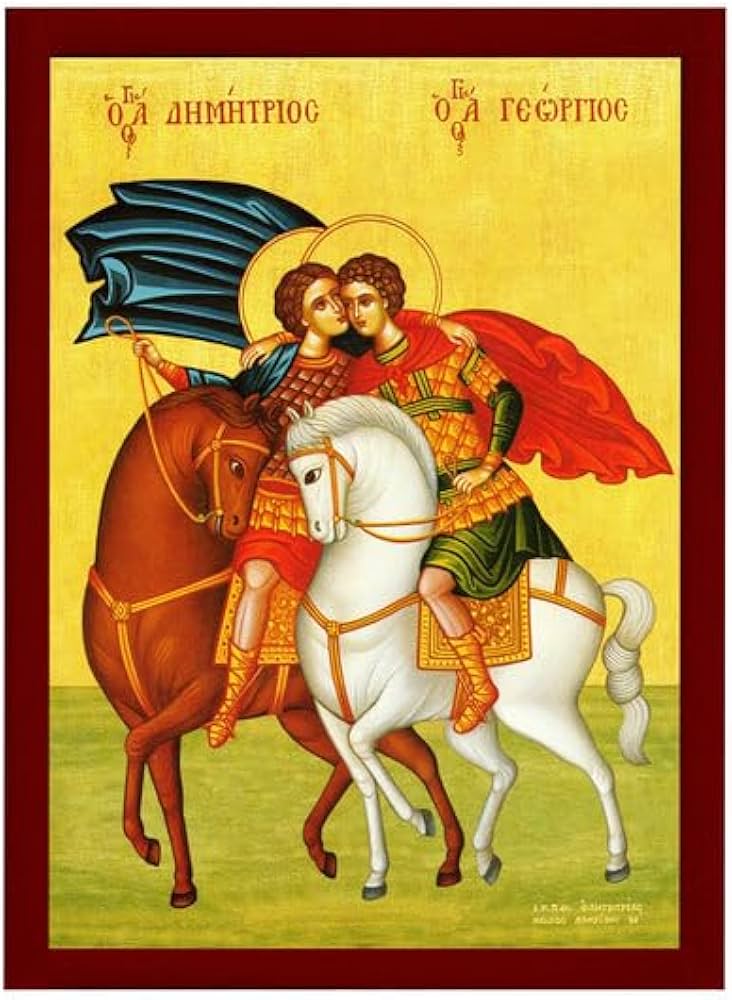

- St Geoges and St demetrios … the twin Brothers

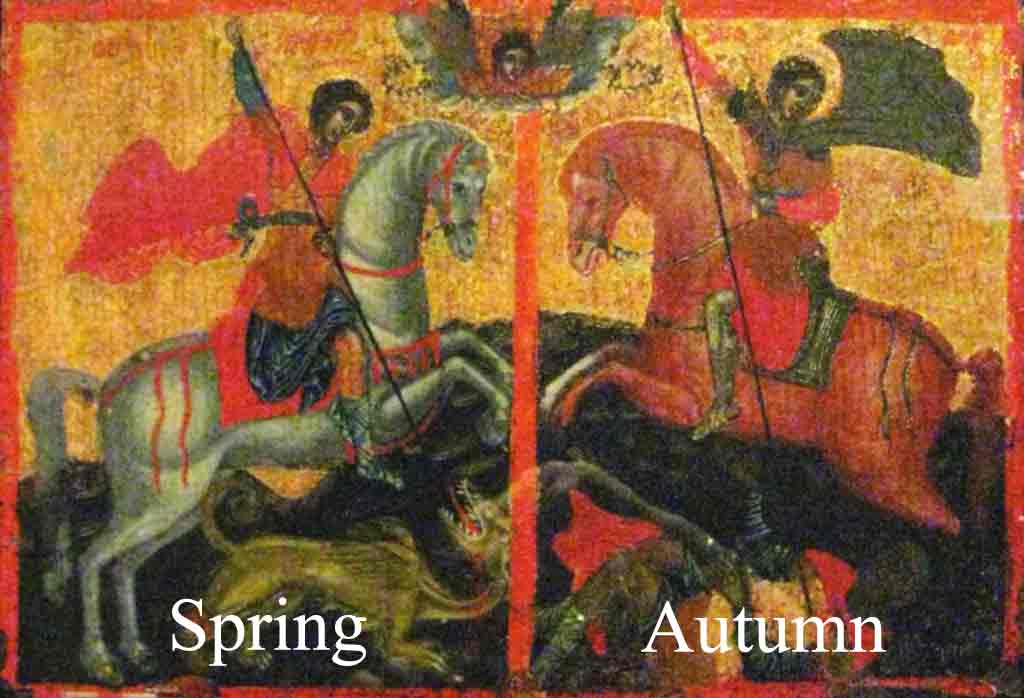

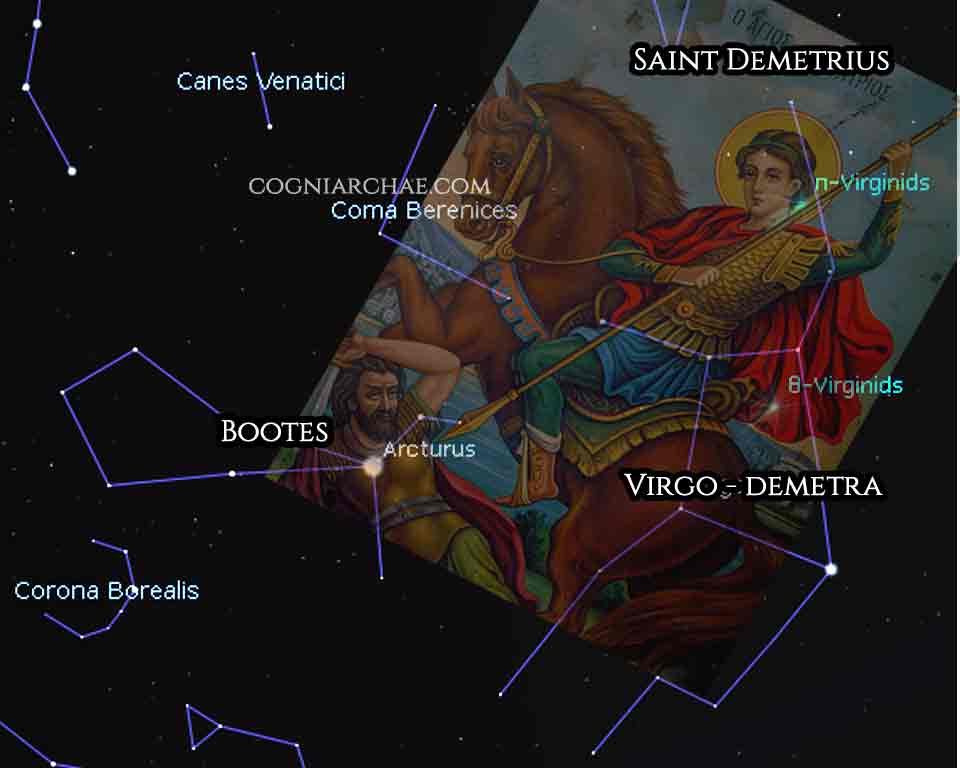

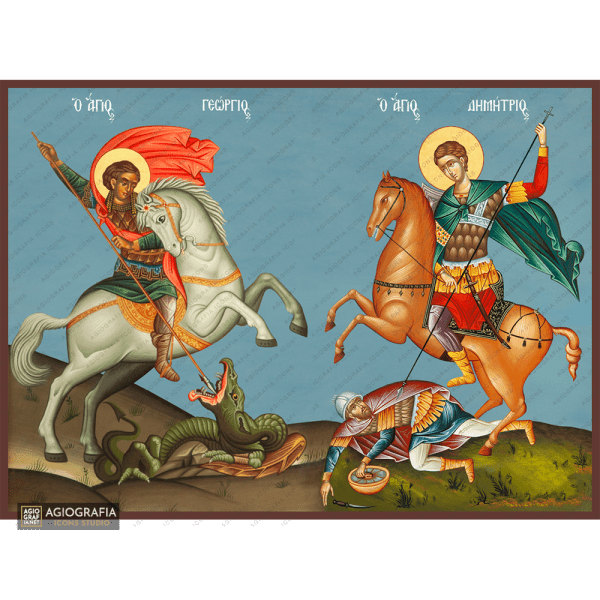

The traditional calendar of Bulgarians in the past had several important dates in the transitional period between the change of seasons. Climatic conditions on Bulgarian lands quite naturally split the cycle of nature into two major parts. The first part starts on May 6th, or Saint George’s Day, when spring arrives and all nature awakens for life. The second borderline is October 26th, or the Day of Saint Demetrius. This is deemed to be the end of the active agricultural season, the start of winter, evening gatherings and engagements of young couples. Just as every new beginning, Saint Demetrius’ Day was a source of much hope. On this day, people would make predictions as to the future fertility, health, love and the weather at the coming Saint George’s Day. Because in folk beliefs, George and Demetrius were twin brothers, that is why the predictions made on Saint Demetrius’ Day were valid for the day of his twin brother.

Saint Demetrius’ Day is a big Christian holiday. On this day, Bulgarians traditionally venerate the memory of the holy martyr Demetrius who was born in Thessaloniki in the 3rd century AD. He died as a martyr for the Christian faith, and upon his grave in Thessaloniki a small church was erected. At the place of this small church, a magnificent basilica stands today, where the relics of St. Demetrius are kept. This is, in a nutshell, his official Christian role in Bulgarian beliefs. In Bulgarian folklore, however, St. Demetrius has been given a special place, and the whole month of October is sometimes called the Month of Demetrius.

In folk beliefs, Saint Demetrius is the elder twin brother of St. George. Both are strong, beautiful and fearless men. Along with St. Theodore and St. Elijah, they are the Christianized equivalent of the brave men in Bulgarian mythology. Strong and dexterous in the battle, with their fast horses they can jump over mountains, conquer evil, and fight dragons. In folk tales and legends, the two saints have the power to open and close heaven, make rain and snow and ensure fertility. The task of St. Elijah was to protect the fields of corn from the evil creatures who stole the harvest. His brothers, twins George and Demetrius, were also strong enough to defeat the mythical monsters. They are represented as warriors and victors also in Christian iconography. Saint George is riding a white horse and Saint Demetrius a red one, both holding a spear in hand.

The most popular legend of the brothers George and Demetrius contains facts from the life of St. Demetrius. It tells about the family of a poor fisherman who had no children. The man and his wife constantly prayed to God to give them offspring. One day, the fisherman caught only a very small fish which spoke with a human voice and begged him to let it go. The man did so. The next day, he had no luck again. He caught only the small fish again. On the third day, the same thing happened. This time the fish asked the man to take it to his house. He did so and after a while, his mare gave birth to two foals, and his wife – to two boys. They named them George and Demetrius. When they grew up, they set off on a long journey. They agreed they would divide the world into two halves and everyone would live in his own half. Once, when Saint George was in danger, Saint Demetrius fought with a dragon and saved his life. Then, they mounted their horses, flew to heaven and became saints.

In Bulgarian fairytales, St. Demetrius is also endowed with unearthly spiritual powers. His image is reminiscent of Proto-Bulgarian high priests, legendary healers and fortune-tellers. And he can even predict the weather – that is why Bulgarians used to believe that if the weather on Saint Demetrius Day was nice, so would be it also on St. George’s Day. And who knows, these predictions may as well be true. Or they could be seen just as another bridge between the known and unknown reality that has for centuries put man in anticipation, suspense and hope for a better future.

Note: in Horus, St. George, Jarilo, and the star-lore of the equinoxes Cogniarchae explains: “Supposedly, merely a century after the arrival of his cult to Thessaloniki from the territory of modern Serbia, Slavs came to Balkans, following the same route as St. Demetrius only to be repelled by this Saint in Thessaloniki. I highly doubt this – in fact, I believe that it was the Slavs who brought his cult to Greece, whether this means that they were present in Balkans before the official history accepts or not”.

Look also: Green Man, the Legend of the Rood and the Grail